|

|

|

|

Harappan India

Miles Hodges

|

|

The Harappan Culture

In the Indus river valley (in today’s Pakistan) archeologists have discovered the remains of a number (actually a quite large number) of cities and towns of very ancient existence - dating back to 3000 or even earlier. Two of these cities are quite extensive: Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. We know very little about them except that they developed very orderly urban communities and they seemed to be a fairly non-military society. Oddly, archeologists have failed to uncover anything that might have served as a temple – bringing forth another question about these people. Surely they had a priesthood of some kind – or some kind of moral leaders whose work was to keep earthly society aligned correctly with the world of the divine. The very orderliness of the Indus River communities indicates extensive social order. In fact, it seems even to indicate that the profound order of these settlements constituted something of a kind of rigidity – which may have contributed to the decline and collapse of this society around 1700 - 1500 BC. But this would only be daring conjecture. Actually very little is know about this high civilization. It left a huge record of very orderly urban design, advanced construction techniques ... and little else. No writings or records of its inhabitants and their lives have been found. The splendid remains of this once magnificent civilization simply lie there silently, revealing nothing at all about the life that was actually lived there. Speculation is that the society may have tended to be chthonic in its religion - that is, focused more on the powers of the gods of the underworld rather than the gods of the skies, drawing mostly from the stereotypical religious pattern associated with settled agrarian rather than nomadic herding societies. But this speculation too is far, far, from certain. In short, we know nothing about them. Long has it been the natural assumption of archeologists that light skinned Aryans in invading the North of India in the middle of the second millennium BC supposedly pushed the original inhabitants into the southern delta region, where dark-skinned Dravidian are found today. It was thus assumed that the Dravidians must have been the original members of the Harappan culture. But there has so far been very little evidence connecting the ancient Harappa culture with modern Dravidian culture. Again ... we really know very little about this once great Indus River civilization. |

Extent and major sites of

the Indus Valley Civilization

huntingtonarchive.osu.edu

Harappa

Harappa - artist's

reconstruction

www.harappa.com

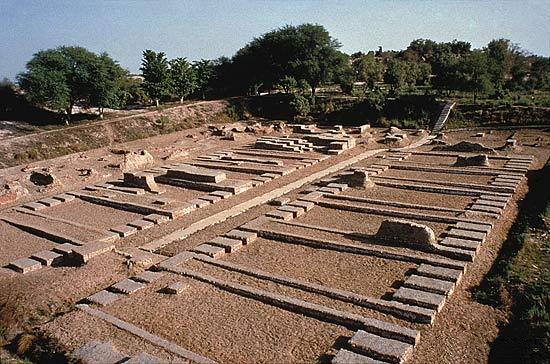

"Granary," Harappa

www.harappa.com

Public Well, Harappa

www.harappa.com

Mohenjo-Daro

A computer-generated reconstruction

of Mohenjo-daro

Wikipedia - "Indus

River Civilization"

Rows of ruins at Mohenjo-daro

reflect

the rigid social order of the ancient culture of the Indus

Valley

The excavations at Mohenjo-daro

The Great Bath at

Mohenjo-daro

Remains of the sewer system

that served the city

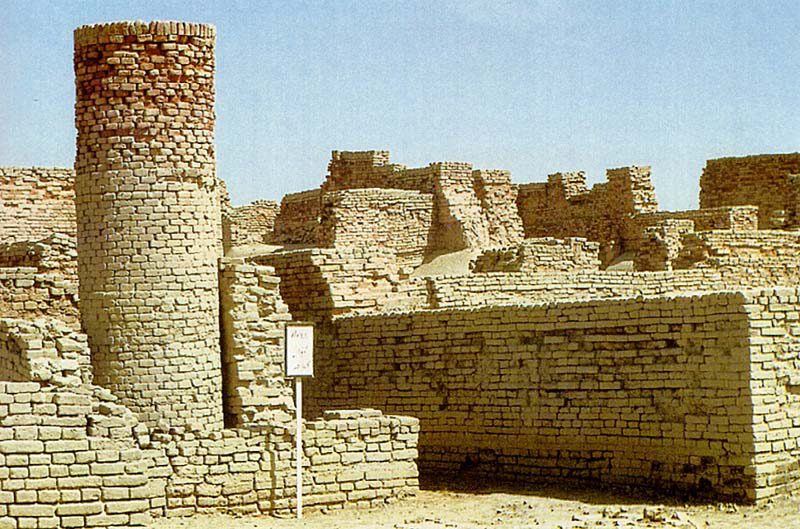

A Mohenjo-daro

street

This private well stands

like a tower because excavations have removed all the earth

that once surrounded

it ... earth built up over the

rubble of many rebuildings of the city

A priest or king ... or deity? - Mohenjo-daro - soapstone sculpture"

The "Dancing Girl" of Mohenjo-daro

Small clay bullock cart from

Mohenjo-daro

Animals, people in meditative

poses, and early forms of writing (?)

adorn tiles made by the

Harappans of 2000 BC

|

|

The Ancient Aryans

At some distant point in ancient history (1700-1300 BC?) nomadic tribes of the North or Western Asia began to push southward – and westward and eastward, conquering settled societies as they went. This process may have gone on for many centuries – in small waves of one after another nomadic conquerors. We call these invaders the ‘Aryans’ from their own word Arya meaning of noble or free birth or origin (the term lives on today as ‘Iran’ and ‘Eire’ or Ireland). They spread West into Asia Minor (Hittites) and Southeastern Europe (Greeks), with the Romans, Celts, Germans and Slavs – also Aryan tribes – following up behind them in later waves. They spread South and Southeast into the Iranian plateau (Medes and Persians being later descendants of these original Aryans) and from there across the gap in the Hindu Kush mountains down into the Indus River basin – where they overran or at least replaced the Harappa society described above (had it already expired before their arrival?). It was around 1700 - 1500 BC that they made this grand move into India –although smaller Aryan raids into northwestern India may have been common well before then. From this position in the Northwest of the Indian sub-continent they spread eastward across the northern Ganges plains, conquering the local population and establishing themselves as a religious, military and even economic aristocracy dominating the rest of Indian society. They brought their Aryan religion with them – a religion which looked to the powers on and above the earth rather than below it. They worshiped a complete society of celestial gods, presided over by the Sky Father (Dyaus Pitar – like the Greek Zeus Pater or the Roman Jupiter). Other key members of this celestial society were Indra (war), Varuna (order), Agni (fire), Mitra (light), Rudra (destruction), Soma (hallucinogenic drink) – bold, daring gods with much the same aggressive bravado of their human heros. Indra, a particular favorite, was not only a bold, boastful, brash warrior who grabbed rather than inherited power, he was frequently a drunkard and a glutton: in short, the Aryan male ideal! (Very much like the Greek poet Homer’s gods and heros of the Iliad and the Odyssey.) He was, not surprisingly, identified with the power of storms and battles. The other early favorite was Varuna. He manifested a more orderly personality, for he was seen as something of the god of good order (rishi). In fact there is evidence that at one time early in the Vedic era, Varuna and Indra were something of competing gods, with competing followers among the Aryans. Vedic Hinduism

Aryan society was not a literate society – but functioned intellectually through poetry and song. From this mindset emerged the Vedas, a large number of ritualistic hymns of praise and petition to the gods – as well as poetic moral sayings – somewhat like the ‘wisdom’ literature of the ancient Israelites (their Psalms and Proverbs). Thousands of pieces (suktas) of Aryan worship and wisdom were eventually organized into four collections (Samhitas) of Vedas, the oldest, longest and most important being the Rig Veda – the other three being the Sama Veda (chants), the Yajur Veda (rituals) and the Atharva Veda (popular sorcery or spells and magical incantations). The last of these, the Atharva Veda was late in being admitted to the status of Samhita – and almost was rejected because it seemed to have arisen more from the animistic or magical temperament of the commoners among the Dravidian population than from the loftier Aryan temperament. Over time (up into the last half of the first millennium BC), the four Samhitas or Vedic collections were expanded with additional works which were organized into three additional categories of wisdom and worship: the Brahmanas (directions for the performing of ritual sacrifices), the Arankayas (the interpretations of the sacrifices) and the Upanishads (philosophical speculations about matters of creation, life and death). By about 300 BC the Vedic worship and wisdom collection of Samhitas, Brahmanas, Arankayas and Upanishads was largely complete. We must be careful of implying some kind of careful ordering of Hinduism – as for example was the case of Christianity under the Roman emperors (such as Constantine) who demanded theological clarity for Rome’s official Christian religion. No such order existed for Hinduism. First of all, the number of gods worshiped in the ancient Hindu community was almost limitless – some speculated that there were as many as several hundred thousand deities worshiped in India. Further – though it was often the case that a Hindu might treat a particular deity as the only god, it was understood that whether one or many, the specific gods worshiped by the Hindus were merely the representation in one form or another of a basic unity of the divinity. The actual gods themselves tended mostly to be representatives of various attributes of the divine – the power of the sun, the skies, the rivers, etc. Further, a particular god might change attributes over time, taking on new traits and dropping older ones. It truly is very difficult to say definitively what a particular god represented to the Hindu. That depended on the era – and even the viewpoint of the particular Hindu. The performance of worship in the early Vedic period was rather ad hoc or impromptu. There were no temples. Rather, sacrifices and worship rituals were performed by a community chief or elder in the open air before a ritual fire. Accompanied by the chanting of suktas and the offering of prayers, ghee (butter) and soma (drink) were poured into the fire. Simple – at least in the early stages of Vedic Hinduism. Vedic Hinduism was fairly optimistic about life – and even death. The proper performance of the sacrifices and rituals gave man control over the devas or spirits which in turn controlled the natural environment. And the matter of life after death was also simply a matter of the proper moral (importantly: bravery) performance of deeds – and also rituals, for they could cleanse a man of his sins and usher him at death into paradise where he would join his forefathers. The alternative was to be cast down into eternal punishment in a realm of total darkness. |

The Khyber Pass through the

lofty Hindu Kush mountains

The Western approach to the

Khyber Pass (Afghan side)

Miles Hodges

The Khyber Pass in the Hindu

Kush mountains

Miles Hodges

|

|

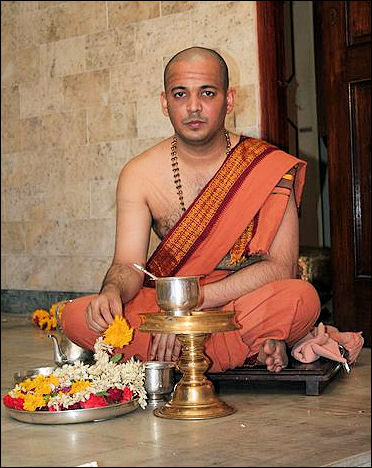

The rise of the Brahmin priests

In fact so increasingly important did the rituals become that certain participants in these rituals grew to have an increasingly dominant role in their performance: the Brahmins (from the word Brahman, which originally meant the power of prayers and rituals to cause the intended effect or outcome to actually occur). The Brahmins were the last of several classes of priests who developed in keeping with the increasing complexity of the sacrificial rituals. The dangers of making a mistake in any part of the performance of the rituals grew in severity – so that the tribal or clan chiefs could no longer be trusted with the task of conducting them. The Brahmanas (sacrificial rules and necessary hymns, chants and prayers) expanded in their content as the rituals became increasingly elaborate. So did the number and variety of religious ‘specialists’ given responsibility to perform the sacrifices according to the Brahmanas. There were priests who prepared the increasingly elaborate altars, those that cared for and employed the tools for sacrifices, those who sang or chanted during the sacrifices. Then finally a new class of priests made their appearance: the Brahmin priests whose job was to coordinate or supervise the whole elaborate affair to make absolutely sure that no mistakes were made in the performance of the sacrificial rituals. The making of a mistake was far worse than offering no sacrifice at all. Mistakes would have to be corrected by even more elaborate rituals – conducted by the Brahmin priests. Eventually the Brahmin priests became the most important individuals in the life of the Hindu community – greater in importance than even the tribal or clan chiefs. But this Brahminic power led to abuse – as the Brahmin priests assumed additional magical powers, to bless ... and to curse. The gods themselves even supposedly fell under the spell of these Brahminic powers. Thus the Atharva Veda and the Brahmanas (by the middle of the first millennium BC) came to be filled with powerful mantras (chants) and the ritual casting of spells that gave these Brahmin priests seemingly unlimited powers. The rise of princes and kings

But secular power also developed as Hindu society became more settled and ordered. As Hindu society developed in complexity, clan and tribal leaders took on the responsibilities of governance from a more lofty remove from the rest of society. These governors were becoming princes or kings – or rajas. They worked closely with the dominant Brahmins – exhibiting their royal powers not just in the conduct of war but perhaps even more importantly in massive festivals (births, marriages, deaths or simply religious holidays), in which hundreds of animals (even sometimes humans) would be offered up in sacrifice in demonstration of the raja’s wealth and power. The castes1

Thus it was that under the Aryans, India developed a well-established class system of: priests (Brahmins), rajas or military chieftains and aristocrats (also known as Kshatriyas) and – ultimately – the commoners (Vaisyas). A fourth class probably added at the time of the Aryan conquest was the Shudras, referring to the dark-skinned Indians (descendants of the previous inhabitants of India) who functioned as servants of the Aryan castes. And for the truly downtrodden (with the darkest of all the skin colors) there was the category of Pariah or "outcaste" - for whom the most demeaning occupations (such as cleaning latrines or handling dead bodies) and the most meager of social benefits were accorded. This class system easily evolved into a "caste" system in which the various social classes could be easily identified by skin color (thus the word "caste," meaning color or hue), with the lightest-skinned being the ruling Brahmins and Kshatriyas, the darkest being the Shudras and Pariahs – with the Vaisyas being a light-dark mix. This caste system was further organized into a quite rigid hierarchy of thousands of jatis or birth groups, sub-divisions of one or another of the castes, each jati dictating by birth a person’s occupation, eligible marriage partners, types of religious rituals to be performed and all types of behavior required of or appropriate to each clan and its families into which a person was born. Dharma and karma

Dictating the shaping and working of this intricate caste system was a set of social or religious ideas built around the concept of dharma. Dharma was the full set of religious truths and social requirements that dictated the thought and action of each jati – which each member of a jati was supposed to follow precisely. Supporting or enforcing this system of dharma was the concept of karma. Karma was the the consequences for a person of the performance of both good and bad deeds. Each person had the responsibility of performing properly one’s duty (dharma). In turn, the performance (or non-performance) of a person’s dharma determined that person’s consequences in life, both good or bad (karma). The resultant social order

This system of moral cause and effect working on each individual (and overseen by the small ruling council of each jati) served wonderfully to keep almost a natural social order in India. As result ancient Indian society did not really develop the idea of the "state" or "government" quite the way we moderns know it today. The Kshatriyas or princely caste were assigned territories over which they ruled and which they protected and exacted taxes for their protective services. But the institution of law and order had little to do with their governance. That was a matter of the workings of the religious caste system. And it worked fairly well indeed (unless you wish to make an exception of a fraternity of professional bandits, the thuggees (or "thugs"), who turned their occupation of murder and robbery into a religious function honoring the Hindu goddess Kali – thus supposedly doing no disservice to their karma!). 1The term caste is actually derived from the Portuguese word casta for color or hue ... used by the Portuguese in the late 1400s when they arrived in India and discovered that Indian society was divided into various social classes, easily distinguished from each other by the color or light/darkness of their complexions. |

A Brahmin priest

A Kshatriya prince - the Maharaja of Cutch, Khengarji III (c. 1900)

Thuggees (c. 1894) ... born to the call to plunder and kill (mostly travelers on the Indian roads)

The Monsoons of India

Wallbank

| Monsoons run from June to September, wet air currents drawn from the Indian Ocean by the extremely hot high-pressure areas over India, built up since March. When this air meets the cool along along the Mimalayan mountains, it drops its moisture, with the heaviest downpour being in India's northeast. The monsoon give India 90% of her annual rainfall. Then from October through January the winds reverse direction, bringing cool, dry breezes from the north. This movement of air reaches even out over the India ocean, making for prevailing winds which move sailing vessels quickly across the Ocean from East Africa, making for a much more rapid crossing than the slow coastal route. |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges