DE RE PUBLICA

(CONCERNING THE 'REPUBLIC'

OR 'COMMONWEALTH')Book Four

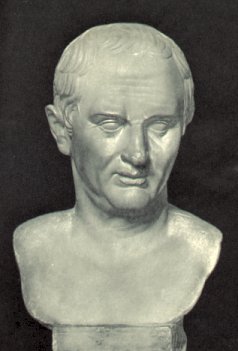

by Marcus Tullius Cicero

Translated by

Francis Barham

FRAGMENTS The great law of just and regular subordination is the basis of political prosperity. There is much advantage in the harmonious succession of ranks, and orders, and classes, in which the suffrages of the knights and the senators have their due weight. Too many have foolishly desired to destroy this institution in the vain hope of receiving some new largess by a public decree, out of a distribution of the property of the nobility.

You cannot too deeply consider the political precautions so wisely adopted, in order to secure to the citizens the benefits of an honest and happy life, which is, indeed, the grand object of all political association, and which every government should endeavour to procure for the people by its laws and institutions.

I think that we have, perhaps, been hitherto too inattentive to the national education of the people. As respects the custom of liberal education, to promote which the Greeks have often laboured in vain, it is the only point on which Polybius accuses the negligence of our institutions. For the Romans have thought that education ought not to be fixed, nor regulated by laws, nor be given publicly and uniformly to all classes of society.

In our ancient laws, young men were prohibited from appearing naked in the public baths—so highly were the principles of modesty esteemed by our ancestors. Among the Greeks, on the contrary, what an absurd system of training youth is exhibited in their gymnasia! What a frivolous preparation for the labours and hazards of war! what indecent spectacles, what impure and licentious amours are permitted! I do not speak only of the Elei and Thebans, among whom in all love affairs, passion is allowed to run into shameless excesses. But the Spartans, while they permit every kind of licence to their young men, save that of violation, come exceedingly close on the very exception they insist on, besides other crimes which I will not mention.

Lælius.

—I see, my Scipio, that on the subject of the Greek institutions, which you censure, you prefer attacking the customs of the most renowned peoples, to playing the critic on your favourite Plato, whose name you have avoided citing.

The drama is an excellent institution, when it is maintained in its original purity, as the teacher of morals by examples. I should love the stage, if the custom of our public manners had not authorized, or at least tolerated, the most scandalous exhibitions in the theatres. Here the more ancient Greeks provided a certain correction for the vicious taste of the people, by making a law that it should be expressly defined by a censorship what subjects comedy should treat, and how she should treat them.

For all this, the Greek stage was continually abused and corrupted, to gratify and flatter the hallucinations of the mob. Whom has it not attacked? or rather, whom has it not wounded, and whom has it spared? In this, no doubt, it sometimes took the right side, and lashed the popular demagogues and seditious agitators, such as Cleon, Cleophon, and Hyperbolus. So far, so good; though indeed the censure of the magistrate would, in these cases, have been more efficacious than the satire of the poet. But when Pericles, who governed the Athenian Commonwealth for so many years with the highest authority, both in peace and war, was outraged by verses, and these were acted on the stage, it was hardly more decent than if among us Plautus and Nevius had attempted to malign Scipio or Cato.

Our laws of the Twelve Tables, on the contrary—so careful to attach capital punishment to a very few crimes only—have included in this class of capital offences, the offence of composing or publicly reciting verses of libel, slander, and defamation, in order to cast dishonour and infamy on a fellow–citizen. And they have decided wisely; for our life and character should, if suspected, be submitted to the sentence of judicial tribunals, and the legal investigations of our magistrates, and not to the whims and fancies of poets. Nor should we be exposed to any charge of disgrace which we cannot meet by legal process, and openly refute at the bar.

In our laws, I admire the justice of their expressions, as well as their decisions. Thus the word pleading, signifies rather an amicable suit between friends, than a quarrel between enemies.

It is not easy to resist a powerful people, if you allow them no rights, or next to none. (Non enim facile valenti populo resistitur, si aut nihil impertias juris, aut parum.)

end of the fourth book

Continue on to Book Five

Return to the Table of Contents

Return to List of Authors and Books