|

|

The "Glorious Revolution" (1688-1689) and its impact on the colonies The "Glorious Revolution" (1688-1689) and its impact on the colonies The colonies' ever-evolving intellectual-spiritual character The colonies' ever-evolving intellectual-spiritual character "Enlightenment" impacts Western civilization in Europe and in America "Enlightenment" impacts Western civilization in Europe and in AmericaThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 89-98. |

|

|

Events in England

James II did not long rule England (only three years: 1685-1688). His autocratic and Catholic ways once again stirred the wrath of a very independent-minded Parliament quick to protect its rights and powers against an ambitious king. What finally set off an armed conflict between King and Parliament was when in mid-1688 a son was born to James, thus effectively ending the possibility of the throne upon James's death passing to his Protestant daughter Mary and her Protestant husband, William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands – who was also her cousin and a grandson of Charles I. Religious tensions had been running high throughout Europe, principally because in 1685 French King Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes, a nearly century-old guarantee that Protestants (Calvinist Huguenots) would have the freedom of worship in France. Much of Protestant Europe was up in arms about this revoking of the Edict of Nantes, reactively forming something of a Grand Alliance under William of Orange's leadership. When in the spring of 1688 English King James concluded a naval agreement with France, suspicions mounted quickly in England that this was the prelude to a formal pro-Catholic English-French military alliance. A group of English leaders agreed with William of Orange that it was time to act. Soon a coalition was formed against James II and Louis XIV, which oddly enough included, at least indirectly, the very Catholic Holy Roman (Austrian) Emperor and the Pope!1 The French king took the first action – which then led to full-scale war. Now it was the turn of William to act. He quickly gathered a huge Dutch naval invasion force – to which James responded rather feebly. With William's landing in England, noblemen began declaring themselves as Whigs for William. James began to lose courage quickly, fearing even the loyalty of his own Tory army. Defeat in small skirmishes and growing anti-royalist or Whig rioting in England's cities decided him to flee to France in mid-December. But he was caught before he could complete his escape and was returned to London. However, William did not want the responsibility of taking personal action against his uncle (also his wife's father). Clearly, the best strategy was to allow James to again escape to France. And so at the end of December James slipped off to France to live in exile as a guest of Louis XIV. Parliament quickly (February 1689) empowered William and his wife Mary to rule as joint sovereigns – under the authority of Parliament. William would rule as English King William III until his death in 1702; Mary would co-rule as Queen Mary II until her death in 1694. Parliament also passed a Bill of Rights (December 1689) clarifying the rights and powers of Englishmen and their government. England still had a monarchy (which it does even to this day) but it was in fact under Parliament's unquestioned sovereignty. Thus to most of those viewing those events, this was indeed a Glorious Revolution.

Events in the American Colonies

James had been no less autocratic in his handling of the American colonies. Upon his gaining the throne in 1685, he had abruptly canceled all the charters, constitutions, and compacts of the Northern and Middle American colonies. He intended to unite these colonies into a single Dominion of New England, ruled from Boston by his royal governor, Edmund Andros. Anti-James (or anti-Jacobite) hostility grew quickly in the colonies. With the outbreak in 1689 of fighting in England between William and James, New York militia captain Jacob Leisler deposed the royal governor and placed himself in control of a newly democratic New York. When in 1691 the recently crowned William sent his own royal governor to New York, Leisler was not willing to step down. A small military showdown had Leisler and his circle arrested. Leisler was tried and hanged as a traitor – and the Leisler Rebellion quickly died down. In Boston the reaction to the news of the war in England was the same. Rebels took control of the city. Fearing for his life, Governor Andros attempted to flee Boston, but was caught dressed as a woman. He was then sent back to England for trial – but was released upon arrival in England. Ultimately William renewed all of the charters of the New England colonies and things returned to normal. But the colonists had demonstrated that they could be just as quick to defend their political rights as the English Whigs. Indeed, the term "Whig" would eventually be assigned to the colonials who in the later 1700s would move America away from the tyranny of royal authority to an independent American republic, and the term "Tories" to those who chose to stay loyal to the English king.

The Matter of English or British Rule Heading into the 1700s

Over the next quarter of a century English royalty changed hands, from the Stuart family to a family of distant cousins in Hanover, Germany. When King William died childless in 1702, the throne of England passed on to Anne, the sister of William's deceased wife Mary. But the sickly Anne also had borne no heir of her own, and when she also died childless in 1714, something of a crisis descended upon the Kingdom of Great Britain (the name of the union since 1707 of England and Scotland). There was no way that the British Parliament was going to permit any of the very Catholic Stuarts still in exile on the European continent to return to the throne, and the 1701 Act of Settlement outlawed that possibility anyway. Thus at this point the British had to perform a huge genealogical stretch to find a Protestant kinsman to take the British throne. Finally, the selection came to that of the distant German (Hanoverian) kinsman, George of Brunswick Lüneburg, who as early as 1710 had made it clear that he was the proper successor to the British throne. And so he was. But his accession to the throne was the signal for the Tory-supported Catholic Stuarts to spark a Jacobite rebellion in Scotland, which was quickly put down – but handled mercifully by the new king. At this point British politics focused primarily on foreign events, especially the dynastic conflicts among the various royal families of continental Europe, conflicts that the American colonies would be caught up in. George's rule of Britain (1714-1727) was loosely held. He spoke no English and left most domestic governmental matters to his cabinet ministers, thus allowing English government to move more closely to the notion of cabinet rule. At his death in 1717, his place was taken by his son, George II (with whom he had personally maintained only a cold and distant relationship), also not an able English-speaker, who, like his father, continued the policy of leaving domestic politics to his cabinet so that he could participate fully in the game of foreign diplomacy and warfare. 1It

seems that at that point in this new age of post-Christian

Enlightenment, dynastic rivalries now played a much bigger role than

old religious loyalties, even for the Catholic Pope! |

Sir Edmund Andros – Governor

of New York - 1674-1681

Governor (1661-1692) and Proprietor

(1675-1692) of the Maryland colony

Enoch Pratt Free Library,

Baltimore

William of Orange – English King as William III

1689-1702

portrait

by Sir Godfrey Kneller

National Galleries of Scotland

|

|

The Halfway Covenant

Meanwhile the Puritan colonies of New England had settled in quite well. Life was very comfortable there now as the 1600s continued. The first New England generations of Separatists and Puritans, who had braved the dangers of founding new colonies in the wilds of North America, were now followed by generations quite familiar with security and prosperity, and thus began to evidence the ancient pattern of the Biblical Israelites. These following generations of Puritans were much less reliant on God for their fortunes, much less spiritual, and much more materialistic in their approach to life. Their lives evidenced little of the spirituality, the mark of true Christian faith, that had been stressed by their elders as essential to being received into full membership in the church – and thus also in the Puritan political ranks. A bit of a quandary thus emerged, concerning the bringing into the Divine Covenant of infants of the true born-again parents by way of infant baptism. What was to be done about the infants of those later-generation parents who had themselves not yet given to the community a demonstration of their own true conversion? Were their children to be denied the right of the baptismal covenant because of the parents' shortcomings? In 1662 a compromise was put forth by the community's pastors and elders: the younger generation of Puritans were offered a new, less rigorous qualification for church membership. The younger generation would be accepted into partial church membership, a Halfway Covenant, where their children could be baptized, although the unconverted parents would still not be allowed to participate in the celebration of the Lord's Supper or to vote on church business. The hope for these halfway convenanteers however was that they (and subsequently their children) would allow themselves to be guided and instructed by more mature full members, until such time as they could finally demonstrate a readiness by way of the conversion of their souls, one that qualified them for full membership. But for many, such a time of readiness never came. They either could not convince the more strict, older Puritans of the authenticity of their conversion in the Christian faith – or they simply just delayed and then lost interest in going through the requirements of full church membership. Besides, there was a growing trend (Maryland, Connecticut, and Rhode Island setting the early example; the proprietary colonies of Charles II following up on this idea after 1660) of separating political participation in colonial government from the requirement of church membership. Thus the original ideal of the Puritan societies, uniting both spiritual and political activities as essential to true Christian life, began to lose its hold on the newer generations. They did not at all walk with God the way their elders had.

The Salem Witch Trials

Much attention has been focused on the events of 1692 and early 1693 concerning the accusations, trials and executions of witches in Salem (actually other towns of Massachusetts as well). In not too subtle ways this event is brought out as a general indictment against Puritanism in general – and today's American Christianity (or at least Protestantism) which is so clearly a direct offspring of the Puritan legacy. It also served recently as a coded story (as per Arthur Miller's 1953 play The Crucible) of encouragement to those being subject to the attacks in the early 1950s of U.S. Senator McCarthy, who was orchestrating an hysterical anti-Communist witch-hunt to cleanse America of the terrible Communist political disease that affected the country, even in high places (or especially in high places) – at least as McCarthy saw things. But what exactly did this event so long ago actually mean? Was it typical of Puritanism in general? Or was it some weird, deviant event in the otherwise honorable history of American Puritanism? Certainly Puritanism itself had lost much of its original character by the late 1600s. Puritanism was being pulled in several directions at once. A growing Secularist worldview among a new breed of intellectuals was challenging Puritanism's old truth-claims. The religion had also settled into a rather stale, legalistic format, leading many people to seek some kind of spiritual relief by turning to more primitive religious instincts, such as a belief in witches. A sense of spiritual conspiracy or just plain old hysteria also played a huge role in letting things move along toward terrible results. Certainly the times were right for conspiracy theories and the hysteria which causes and also results from a sense of the loss of order in life. Much cultural, social, economic and political uncertainty was burdening the Massachusetts colony at that time – especially as the colony became increasingly rationalistic in its worldview and thus more expectant of things to follow an orderly pattern (which their Puritan ancestors would not have expected). On the other hand, for the less-enlightened, it was reasonable in its own way for them to look to the works of the devil and demons as an explanation for the recent Indian uprisings, and the fact that the economy was sagging because the soil was becoming overworked and was overburdened by a growing population it could no longer support. Also, at this time witchcraft or at least the occult was not uncommon as a practice in Western society, raising the wrath of conservative Christians. France, Sweden, Germany, and other European countries had conducted numerous witchcraft trials over the years since the 1400s, especially during the early 1600s. The height of the Swedish scare in fact was only seventeen years before the Salem events, and in Sweden resulted in numerous executions of those accused of practicing witchcraft, in one instance seventy-one executions in one day alone in 1675. In short, this was not something unique to just Puritanism. The witch event in America actually started off in February of 1692 as an outbreak of very strange behavior of two girls in Salem, Massachusetts, which then spread to a number of other girls. At first, several older women, social outcasts of one variety or another, were accused of dabbling in the occult (as many did at that time), even of being witches, causing this strange behavior of the girls. This accusation led to others, finally exploding into a general hysteria in the town of Salem. At trials in March and April, people accused of witchcraft in turn accused others of practicing witchcraft as well. The witch hysteria meanwhile had been gathering momentum, spreading to other villages in the area. But by the summer, the colony's Puritan leaders were urging caution in the process, for judges to be increasingly rigorous in demanding more exacting proof of reputed behavior. Thus slowly the momentum to accuse others began to slow down. Nonetheless executions of those already found guilty started to take place in the late summer, at the same time that new trials were resulting in people being found innocent of the charges of witchcraft. Nonetheless, when the momentum finally died in early 1693, by that time, 200 people had been accused of being witches, nineteen people had been found guilty and put to death and five had died in prison. Within a few years after this event many of those who had been responsible for the wild accusations were backtracking on their earlier claims, even eventually coming to full repentance for their actions. The authorities in fact even had moved to a willingness to give financial restitution to those who had suffered either directly or indirectly (descendants of those put to death) from the trials.

The Social-Cultural Legacy Left Behind by This Event

Nonetheless, this hysteria deeply undermined the integrity of the Puritan experiment, giving rise to thoughts of more enlightened individuals to move to a purely scientific (Secular-Rationalist) approach to life. This move to a more Secular worldview would even sweep up many leading voices in the church. And it certainly would provide Secularists of any age – especially today's Secularists – all the proof they needed to demonstrate that any kind of thought about supernatural forces, including the existence or at least continuing involvement of God, is not only foolish, it is downright dangerous. And thus it is today that Puritanism has become a slur word, and all of the very best of the Puritan legacy (middle-class democracy) has been ignored and even despised. Secular Rationalism or Humanism has taken the seat of cultural dominance in America today, justifying itself by presenting this brief episode in the Puritan era as the summary statement of all that Puritanism ever stood for, also justifying its call to reject such religiosity at all costs. |

The Mason children in their adult-like Puritan Sunday-best attire - 1670

Fine Arts Museums of San

Francisco

Trial of George Jacobs of Salem for witchcraft – August 5, 1692

|

|

The Rise of a Robust Spirit of Intellectual Enlightenment

By the early 1700s the European Enlightenment had indeed taken huge steps in putting aside the Puritan religious culture - both in England and America. Logic and a common-sense approach to life was moving rapidly to replace the previous Christian piety of the early Puritans, and for that matter throughout much of Christian America in general. Churches found themselves fairly empty on a Sunday morning – and the pastors complained much about the loss of Christian faith afflicting the colonies. At the same time, many prominent Americans, taking their cues from the strong intellectual or philosophical trends arising in Europe, were becoming more confident of their own intellectual gifts, their own personal enlightenment, their own powers to fathom the mysteries of the universe through personal study and, of course, through the application of ever-expanding human logic. The old spiritual affections of the early Puritans increasingly appeared to the well-educated American as being nothing more than the result of mere superstition. And the concept of God was slowly turning itself into little more than the idea of the One who long ago set out the self-operating fundamental principles of natural philosophy.

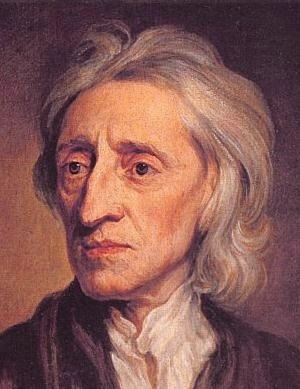

John Locke

Without a doubt the one individual who would have the greatest impact on this Secular-Rational trend in the English-speaking world was the English social and psychological philosopher, John Locke. We have already mentioned Locke's effort in 1670 to draft a constitution for the Carolina colony. Despite the fact that Locke's Grand Model proved to be too utopian to find practical application in the Carolina wilderness, he was hardly slowed up in his efforts to bring a more rational approach to society and its improvement or reform. Indeed, his further studies were received with such acclaim among the community of intellectuals that Locke left a deep and permanent mark on Western philosophy, in America as well as in Europe. In his Two Treatises of Government, written in conjunction with the overthrow of the Stuart monarchy of James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689, Locke in the Second Treatise laid out clearly a very comprehensive worldview that was widely accepted as brilliant and totally compelling, at least to the rising class of enlightened intellectuals. Locke based this worldview on the belief (a belief held by most everyone in those days) in man's tendency to self-preservation and self-promotion. But he also believed that man was inherently reasonable and would freely submit to society – as he saw personal or selfish advantage in doing so. Locke contributed further to the growth of the Secular worldview in another field of endeavor: psychology. In his work, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Locke treated human life as if it were simply another machine in its operation. His studies of epistemology (why or how man comes to know what he knows) had a tremendous impact on Western thinking about the process of learning and enlightenment. To Locke's way of looking at things, the human mind or brain at birth is simply an empty slate (tabula rasa) upon which, as the child begins to encounter life, data ("sensations") from outside the individual are received by the senses and transmitted to the brain. Locke understood that the mind also had, by some kind of instinct, certain abilities through self-reflection to manipulate this incoming data, by associating ideas into working information. In an Aristotelian fashion, he saw man as able to categorize and organize logically this information into the knowledge he would need to thrive in life. It was all very mechanical, this process of thinking and learning. Locke's philosophy was well greeted by the English Whigs who were looking for justification for bringing James II's government under Parliamentary restraint. James, of course had based his right to expect unquestioned obedience to his rule by his English subjects because he had been appointed to his position as king by God himself. And who would dare to question what God had willed for England? This was of course the classic Divine Rights Theory of kingship proclaimed widely throughout Europe at the time. But Puritans had questioned this theory under James's father, Charles I, stating that God had appointed to all of his faithful believers a degree of personal sovereignty. The Bible itself supported this view, and how could Scripture be questioned, even by kings? But now Locke had come along and presented a view of life as a natural matter, complete with its own natural laws. And how could an intelligent person question such natural logic? This had nothing to do with God, either good or bad. It was purely natural philosophy (the grandfather of modern science). With Locke's contribution to Secular thought, the possibility of producing heaven on earth through enlightened human understanding seemed to be beyond the question of any reasonable or enlightened person. God was not a factor in any of this enterprise of social reform. God was no longer needed. History belonged to man, and the decisions he alone made. According to Locke, this tendency of man to pursue what he understood as self-interest thus could be employed to form a civil society, one able actually to achieve human goodness and development, if properly directed. It simply needed the right mechanical political and economic social instruments (or government) to bring that about, designed and managed by those who were enlightened to these mechanics. In short, government was in reality nothing more than a machine, a mechanism – put together by the consent of those who formed the civil society which this mechanism – by way of its officers – directed or governed.

Deism

Step by step a new worldview was rising rapidly in Europe and America, one which stood halfway between traditional Christianity and the rising world of scientific atheism (which was not as widespread in America as it was in Europe at the time). It was called Deism. Deism believed that God had wonderfully assembled all creation in its present, perfect pattern of operation. God was much like a watchmaker, crafting a perfect self-running instrument. But now wound up, life operated entirely on its own, according to its own natural laws, the iron laws of nature that scientific inquiry was discovering with breathtaking rapidity. Natural philosophers (researchers focused on learning about nature and its ways) were beginning to see the earth (and the heavens) simply as machinery – like the well-crafted watch – every item on earth operating according to strict mechanical laws, laws easily discernible by any logical mind. True, not all laws of nature had yet been discovered. But they were out there, waiting simply for the scientific mind of some natural philosopher to finally uncover them. It was all very exciting, watching life seeming to come under the total mastery of man – or at least under the mastery of the Enlightened Ones of mankind. Meanwhile, in such a universe running under its own mechanics or laws of nature, God played no further role in the day-to-day events in life. He was now in some kind of distant retirement. It was up to man now to get along in life according to his own knowledge of how the watch operated.

"Enlightened" Christianity Attempts to Reform Itself

This piece of logic was so compelling that by the early 1700s even theologians and church officials began to call for a reform of traditional Christian understanding of the Bible – to drop the idea of original sin and to clean up the parts of Scripture that relied on miracles to sell the important moral points that Christianity engendered. Enlightened Christians would in fact perfect their faith by getting rid of such superstitious material and focus purely on natural religion, that is, the moral instruction found in Scripture. Jesus was thus viewed by such Christians – John Tillotson, archbishop of Canterbury, 1691-1694, being such an example – no longer as Savior of sinful men but as moral instructor to those who wanted to perfect their lives. Ah, once again Christianity was sliding into Unitarianism! Even before the 1600s were out, there had been a call within Christianity itself, notably from bishops in the Anglican church, to reform itself, to make it more enlightened. Miracles such as Jesus walking on water, or his raising the dead, or Joshua stopping the course of the sun across the sky in order to gain sufficient daylight time to fully defeat his enemies, etc., were raising all sorts of arguments. Some sought to justify these miracles on rational grounds, which by definition makes them no miracle at all, such as the Irishman John Toland in his controversial book, Christianity Not Mysterious (1696). Others, such as Matthew Tindal in his book, Christianity as Old as the Creation (1731), called for Christianity to avoid such questionable or superstitious matters and instead focus itself on the moral-ethical teachings that abounded within Christianity – and for that matter within all the religions of man which have arisen everywhere in the world out of man's natural religious instinct. Thus to such enlightened individuals as Tindal, excellent moral conduct was the supreme virtue of any faith, a virtue and related intellectual discipline that was placing in man's hands the responsibility of seeing heaven brought to earth, as Jesus himself had talked of. This was all very logical. But to the human spirit, it was deadly. Little wonder that the church of the early 1700s was losing steam. |

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges