|

|

The process of coming to an agreement The process of coming to an agreement A Federation replaces the Confederation A Federation replaces the Confederation A government that draws its powers from the people – not vice versa A government that draws its powers from the people – not vice versa What were the guarantees that this would work? What were the guarantees that this would work? The Federalist Papers and the process of ratification The Federalist Papers and the process of ratification The geographic redesign of the Union The geographic redesign of the UnionThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 156-173. |

|

|

A

note of caution here

It is extremely important to note that the delegates who gathered in Philadelphia to devise a new political formula for the purpose of a closer political union among the thirteen states, were not (like the French) inexperienced in republican self-government. Not only had Americans been operating for years under the Confederation government, but the states these delegates represented had already put into effect their own constitutions as independent states. Thus each of them had a pretty good idea of what American government was to look like, at least in principle. Indeed, Americans had been practicing some form or other of constitutional self-government since their ancestors put England behind them in coming to America, some century and a half earlier.1 Thus it is important to note that these Founding Fathers of the late 1700s were not inventing self-government. They already understood quite well the principles involved in effective self-government. Rather, they were trying to figure out a formula for collective self-government that would allow them to continue to work together as a union at a level higher than each newly independent state. They were not naive (like the French, and like many Americans today), believing that some utopian formula discovered by some political genius among them was what they needed. Rather, they knew that each delegate that gathered there had a somewhat different political agenda he would be pursuing – and they were going to have to work together in full respect of those different agendas or interests if together they were going to find the necessary common ground on which to build a new union government. With the benefit of considerable political experience, and with God's counsel opening their hearts to each other, they would succeed. In short, American government itself was not birthed in 1787 – as we so often tend to imply when we talk about the birth of the Republic that year. Actually, long-standing traditions in American government were simply adjusted to meet the ever-clearer needs for a more effective union among the thirteen newly independent states. Divergent interests

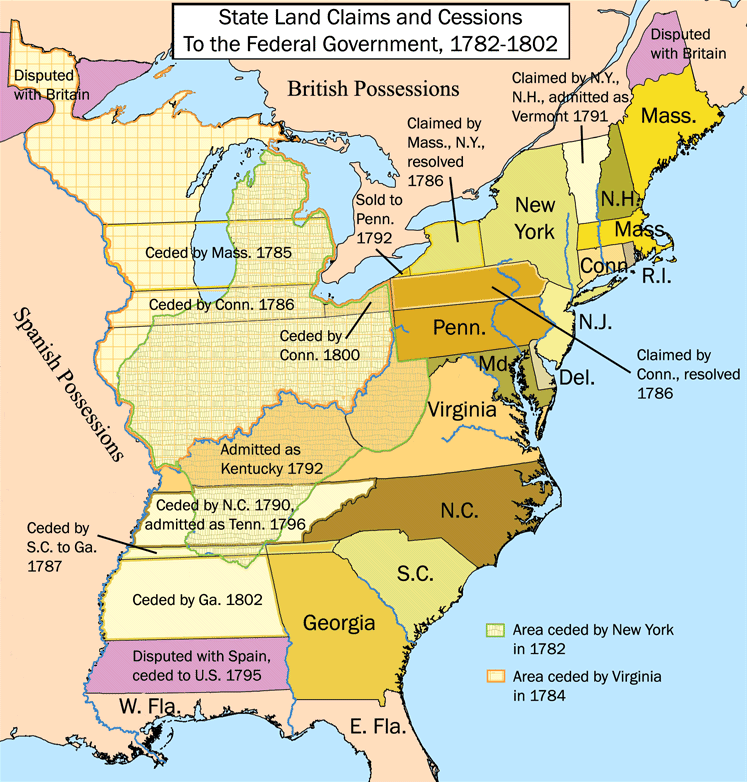

By no means did the fifty-five delegates who gathered in Philadelphia at the end of May in 1787 have the same idea, some widely agreed upon logic, as to what was supposed to result from their work. They represented not only a wide array of states, big and small, but also different life-styles (major plantation owners, prosperous urban tradesmen, lawyers, etc.). The states they represented also found themselves in deep contention about how exactly their particular borders extended to the West beyond the Appalachian Mountains. And most important, they held very different ideas about what kind of government reforms they wanted to see take place. Federalists and Anti-Federalists

Some like Washington, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison were strong nationalists or Federalists who were hoping to see a much stronger political hand holding the thirteen states together. But others who came to Philadelphia were of the opposite opinion, thus strongly Anti-Federalist, fearing that just such a political union would usurp the very freedoms they had so recently fought to secure against the ambitions of the English King George III. In fact, major figures in the recent War of Independence, such as Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry had refused to participate in the Convention, fearing that it would saddle them with just such a government. Likewise, the tiny state of Rhode Island did not even bother to send participants to the meeting, fearing the loss of their independence to the interests of the larger states such as Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The Virginia Plan

His Virginia Plan provided for a bicameral legislature of two separate bodies, an upper and a lower house, on the order of the English Parliament with its House of Lords and House of Commons, a principle followed as well in the design of the governments of most of the individual states. In this it departed from the Confederation's single or unicameral assembly (the Continental Congress), which had demonstrated how a unicameral legislature tended to be easily susceptible to the swings of political mood which accompanied popular politics (politics of the people). The hope was that a second legislative body could counterbalance the passions of a popular assembly because, like the English House of Lords, the second body would be expected to be made up of a smaller group of more distinguished statesmen. However, how that group might be chosen was left open as a key question. Also Madison's Virginia Plan provided for a stronger, more independent executive, not quite like a king but stronger than the executives of the Confederation – and many of the states – who were largely dependent on the legislative bodies for their powers, and thus lacking in any significant power to direct and lead the nation. Anyway, most of the delegates were expecting Washington to head up the new government, and it was important to assign him sufficient powers and independence of action to bring his talents to full service to the country. But the question remained: was he to be the sole executive (and thus more like a king) or was he to share his function with one or two others (as was done anciently)? What would be his term of service: serving for life (and thus indeed like a king), or elected, and probably re-elected, annually or for periods of greater length? And there was the matter of the judiciary or body of judges, who by English tradition were extensions of the king's authority. Efforts of the states to make their judges instead dependent on the appointive powers of the legislatures had produced less than distinguished judges, and elements of well-known political corruption. How such judges should be selected was thus a major problem that brought on much debate. The debate begins

The first issue to come under heated debate was the selection of the representatives to the new Congress. The Virginia Plan assumed that the size of the representation in Congress (both upper and lower houses) would be on the basis of the number of voters in each state, which would clearly give the bigger states a dominant voice in the new government. But Virginia seemed willing to listen to some kind of compromise that would bring the states together in their thinking. 1The

royal charters of the 1600s that birthed each of the American colonies

were themselves "constitutions" of sorts, describing precisely the

purposes and practices that the colonies were to live by. |

| The smaller states were hoping for equal

representation by the states, irrespective of size. Representing the

interests of the smaller states, the New Jersey delegates thus offered

a counter-proposal to the Virginia Plan which called for the continuing

existence of the Continental Congress as a single unicameral body, with

each member state holding equal representation, despite the size, large

or small, of each state.2 But it would be given new powers such as in

the collecting of taxes and the power to override the state laws. This

gave the smaller states a rallying point to put forward their political

interests. But overall it was an idea that the larger states clearly

were unwilling to accept.

The Connecticut Compromise

One of the issues that would long stir turmoil in the new Republic was this matter of slavery. Almost half of the delegates to the Convention (and all of the Virginia and South Carolina delegates) were slave owners. But in general Northerners tended to be adamantly opposed to the idea and practice of slavery; indeed many of the Northern states had included a total prohibition of slavery in their new state constitutions. But Southerners could not bring themselves to imagine seriously a Southern economy able to function without slavery. Some made it clear that they would not join the new Union if slavery were somehow disallowed. Moreover, the Southern states were adamant on the matter of including their slaves in the calculation of the representation in the House of Representatives. But Northerners were quick to point out that slaves weren't citizens. Thus should they be counted at all? Some Northerners even quipped that since slaves had merely the status of property rather than of free citizen, Northern cattle should be added to the count for the Northern representation in the House of Representatives!4 Ultimately another compromise was eventually reached when it was decided that slaves should count as three-fifths of a person! Anyway, most of the Southern Framers were of the opinion that slavery would soon die a natural death, though they had no idea of how that might happen. And so they basically dodged the issue – and would continue to do so until it blew up in their faces in the early 1860s. 2The Continental Congress which had guided the 13 states during the War of Independence had given each state simply a single vote, regardless of the number of individuals – usually two to six or seven – a state had representing it in Congress. 3It was at this point that Franklin asked the Convention to bring God into its deliberations as a means of transcending their deep differences. 4Indians were never part of the count! |

|

Architect of the Capitol

What

the Framers ultimately came up with as they concluded their work in

mid-September was a central or federal political authority with just

enough power to keep the states working together in a sense of American

unity, but with enough limits to its powers to insure that it would not

fall into the human sin of unchecked power hunger that led inevitably

to tyranny. In a sense what they had finally agreed on was a new treaty of political alliance among the thirteen independent states,5 a treaty stronger than the one that had empowered the Confederation. This new treaty instead provided for a federation, meaning a political union with strong powers (though only in certain carefully prescribed areas of governance) assigned to a central authority by the still quite strong individual state governments that made up the Union. 5Although Rhode Island did not send a delegation to participate in the drafting of the new Constitution, Rhode Island did finally join the Union in 1790. |

|

Congress or the legislative branch of the federal government

The heart of this federation was to be a newly empowered Congress (one with wider powers than the older Continental Congress), which would meet periodically to enact certain categories of legislation for the Union. This Congress, as per the Connecticut Compromise, was to be made up of two separate assemblies. The lower house, the House of Representatives, would represent the American people directly, elected by them and thus giving the new federal Union something of a democratic quality. But the upper house, the Senate, would represent instead the states, each of the participating states being permitted to select and send two of its most respected statesmen to Congress to give direct voice to the interests of their respective states. Also, the Senate was supposed to be something of a more aristocratic assembly, a council of political dignitaries who were to keep cooler political heads than what might be expected of the representatives of the people in the House of Representatives.6 But in any case, Congress would be able to function only as both the House and the Senate worked together. 6However, the Senate was "democratized" in 1913 with the passing of the Seventeenth Amendment, having the voters of each state, rather than the state assemblies, select their two senators.

|

|

The president or the executive branch

Congress was intended to be the political center of the whole system: a place where representatives of the states and the American people themselves might gather to do the business of the Union. But the Constitution provided also for an executive officer, a president, whose primary job was to oversee the ongoing unity of these United States. He was to be no king but only a political supervisor elected for a term of four years (presumably renewable however), elected not by the people, but by the states whose union he presided over. Actually it was the duty of an electoral college to choose the president (called into existence every four years solely for that single purpose), each state accorded a number of electors equal to the number of representatives they were entitled to have in the House of Representatives, plus an additional two electors (as thus also each state had two senators). Each state was given the right or responsibility to decide who those electors were to be, with the important restriction being that they could not be chosen from among the ranks of a state's congressional representatives or senators. The president was given a key leadership duty in being the one to call Congress into legislative session (even call special sessions of Congress if need be) and to report to Congress on his observations as to the "State of the Union." He was also expected to be the enforcer, that is, the one assigned the task of seeing that the laws passed by Congress were indeed faithfully executed or followed throughout the Union. In short, he was seen primarily as an executor of Congress's legislation, although possessing limited veto or blocking power if he deemed such legislation inappropriate to the health of the Union. But even then, if Congress could on a second attempt at passage gather, instead of just the usual simple majority for passage, a full two-thirds vote approving the proposed bill (a much more difficult political feat to carry off), Congress could override the president's veto, and the bill would become in fact actual law. The president did have additional functions that fell to him alone, such as sending and receiving diplomats, symbolizing the majesty of the United States, and along those same lines was given the responsibility of overseeing the country's relations with other countries. He also was given the responsibility of serving as the commander in chief of the U.S. military, a vital role in the follow-up to his foreign policy responsibilities (however he could not actually employ this military except when specifically authorized to do so by the Congress). And also, as Congress met only periodically, he (and his cabinet staff) was given the task of the ongoing or day-to-day administration of the federal system at the all-union or national7 level. 7Actually,

it would be wrong to characterize the United States as a nation at this

point. Certainly citizens had some kind of collective or national

identity as Americans. But that sentiment would develop in depth only

later. At the moment they still saw themselves primarily as New

Yorkers, Virginians, Georgians, etc. |

|

The Supreme Court or the judicial branch

The Constitution also described a Supreme Court of federal judges or justices, largely expected to act in accordance with British legal tradition in seeing to the fair application of the laws of the legislature (Congress) in disputes that might arise with the actual application of the law to particular circumstances. The judges were to see that such disputes were indeed settled in accordance with their well-informed understanding of the meaning of the law (they were themselves lawyers of course). The judges would be appointed by the president, but be able to take office only after a confirming vote by the Senate. At the time it was anticipated that the federal judges would be involved mostly in issues arising largely around this tricky matter of the relationship among the different states of the Union.

The Framers obviously did not foresee that the

judges or justices serving on the Supreme Court (but also the district

courts as well) would step by step go well beyond the scope of the

originally designed Constitution to begin to reshape the law according

to the judges' own "more enlightened" personal interpretations as to

how the law ought actually to read in its application to national life.

By this is meant the justices' ability to shape, revise, or even set

aside the law of the land in accordance with merely the personal

ideological, moral or "rational" inclinations of the nine supreme court

justices themselves – or often only upon the decision of a simple

majority five of the nine justices, against the objections of the other

four. In short, over time, step by step, these individuals, possessing

unchecked and thus unlimited legal powers, would succeed in making the

Supreme Court – not Congress – the supreme legislative or law-making

body found within the American federal system. But we will have more

(much more) to say about this matter in later chapters. The limited powers of the central government

Indeed, there was only a very limited internal or domestic governmental role anticipated for the newly created Congress and President (and Supreme Court) by the Framers of the new Constitution. It was understood that the principal concern of Congress, the unifying voice of the different states and the American people, would be limited to those matters primarily concerning the new Union's foreign civil and military relations with the outside world. There were some domestic responsibilities assigned to Congress. It had a number of financial powers, such as creating its own tax sources; establishing, regulating and protecting a national coinage or currency; borrowing on credit; standardizing the rules of bankruptcy throughout the United States. Congress could establish a Union-wide postal service and post roads. It was to encourage the development of science and the arts through standardizing weights and measures, creating uniform copyright or trademark protections. It was to create uniform rules by which people could attain citizenship ("naturalization"). The most interventionist of the clauses of the Constitution in the domestic affairs of the Union was the power assigned to Congress to regulate commerce among the states (the interstate commerce clause). But interstate commerce was seen simply as the issue of the states raising trade protections against each other – a practice the Constitution was designed to bring to an end. It was not intended as an open door for Congress (or the president or the Supreme Court) to become involved in the internal affairs of America (as would in time indeed become the case). The residual powers of the states in the federal system

So, with the exception of the specifically named powers of Congress to act on domestic issues, the states – and the states alone – were the only part of the federal system authorized to provide the people domestic government, that is, government inside the Union itself, as the American people themselves chose to do so through their representatives elected and commissioned to serve on their state assemblies and governing councils. A republic rather than a democracy

It is important to note that the word "democracy" never appeared in the Constitution. The Constitution did define the political nature of this new political order as being republican – very specifically stating that any new states eventually joining the Union (Kentucky stood at the door expecting to become part of the Union very soon at that point) must be republican in character. The republican character of the Union was a matter that Congress itself was importantly to look after. The rule of law rather than personal or even popular will

To the Framers, democracy, as much as monarchy or aristocracy, implied the rule of the human will, whether the will of the many, of only one or of a special few. The framers understood that any form of government directed by the will of human agents, however many or however few, was easily susceptible to tyranny. Rather, the Framers were looking to establish the rule of law – concrete principles that could be etched into stone or inscribed in bronze (as they anciently had been in the Roman Forum), principles that would stand for all times for the community. Humans and their personal desires would come and go. But laws carefully enacted through the constitutional directives they were putting into effect would not be easily swayed by changing human desires and fancies. No, the new government would be a government not of men but of laws. The Romans had constructed such a political system. They too had believed (in accordance with the ancient Romans' typical love of order over impulse) that a government should be a system of laws, not personal wills. The Framers agreed strongly with this same principle. Their hope was that, unlike the Romans who failed to hold to this fundamental principle, Americans would remain vigilant in maintaining the idea of government as a regime of laws rather than human wills. This was the central idea directing the deliberations of the Framers of the Constitution that summer of 1787. They would create a Republic built solidly on constitutional law. But the question still remained: would the American people be able to maintain this Republic any better than had the Romans? |

|

| Further

securing the rights of the people against governmental tyranny –

through the addition of 10 Amendments. Not surprisingly, the final

draft of the Constitution the Framers put together still left

unresolved considerable concern among some Americans about the dangers

of potential tyranny in this new system. Consequently, in order to win

over the reluctance of such Anti-Federalist or states'-rights people as

Jefferson and other prominent Virginians, a promise was made by the

Framers that the Constitution would be immediately amended upon taking

effect to include a number of additional constitutional Articles

further guaranteeing American freedoms against this new government,

something Americans know today as their Bill of Rights.

Prominent among these guarantees is the very First of these Amendments: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.This Amendment concerning the people's right to worship, speak, read, gather peacefully and petition their government was placed in the prominent position as the First Amendment to the Constitution, emphasizing the guarantee that the new federal authority would not infringe on the personal rights of Americans, rights that Americans had built their lives on and therefore rights that they demanded full respect for by any governing body taking social authority in their world.8 The Second and Third Amendments concerned respectively the right of the people to keep and bear arms, and the forbidding of the stationing of troops in people's homes without their consent. The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Amendments concerned the rights of the people in the official process of an arrest, trial and sentencing. And the Ninth and Tenth Amendments made it clear that the states and the people retained full rights on all matters not specifically assigned by the Constitution to the central authorities within the federal system: 9. The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.These last two Amendments were extremely critical – in promising that other than the powers specifically described in the constitutional document as accorded to the central or national branches of the federation, all other powers of government would remain reserved entirely as the privilege and responsibility of the states, or the people of those states. The question nonetheless remained: would such constitutional guarantees be sufficient to hold back the tendency of social authorities, especially those who see themselves as exceptionally enlightened, to want to expand their powers of control over the people? This was very much part of the great political question that had bothered philosophers since ancient times: quis custodiet ipsos custodes / who (or what) will govern those who govern? Will the people control their government – or will their government control them? Who will be sovereign: the people themselves, or some special government authority towering over them? This matter of sovereignty

This piece of royalist logic did not sit well with the American subjects of the English king. For a century and a half, since they had left England and crossed a great ocean to start life anew in America, they had needed no king to do their thinking for them. For that century and a half they had been left alone to rule themselves. Families and local communities managed their own affairs on a daily basis, and on special occasions when there was a need to do some colony-wide business, they would elect representatives to be their voice in the management of the larger affairs of the colony. They had done just fine as self-sovereigns and resented it immensely, finally to the point of rebellion, when George III and his Tory supporters in Parliament attempted to bring these free peoples under tight royal control. The people's divine rights

Lingering behind this debate was the question of political legitimacy. European kings founded or justified their despotic powers not just on the basis of enlightenment (for even commoners could bring themselves to enlightenment) but also on the basis of Divine will. For centuries European kings had been claiming that they enjoyed their sovereign position because of the desire of God himself that they should so rule. God caused them to be born to this position. So how could anyone question what God had decreed. After all, Deus vult, "God wills it."9 European kings (as they saw things) thus ruled by divine right.

Thus when English King George III invoked divine rights in his attempt to bring the American colonies under his complete control they answered with their own Divine Rights Theory. Again, this is well stated in the opening paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence: We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the consent of the governed ...  Thomas Jefferson elaborated on this a few years later in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), although note that he was talking about slavery in the harshest of terms (odd, he himself being a slaveowner): Thomas Jefferson elaborated on this a few years later in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), although note that he was talking about slavery in the harshest of terms (odd, he himself being a slaveowner):

God who gave us life gave us liberty. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are a gift from God? That they are not to be violated but with His wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just, and that His justice cannot sleep forever.Regardless of the source of the problem (King George's tyranny or the evil of slavery), it was quite obvious that there was a strong understanding in America at the time that the rights of the people did not come from some human authority, nor from some human institution. Those rights (and accompanying responsibilities) came from God, and God alone. So for those who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 to work out the Constitution of a new American government the question of political sovereignty was clear: it belonged (by the will of God) to the people – or to them through the states, which, through their elected representatives, the sovereign people controlled with their right to vote. The rights of the American people did not, and would never, derive from the institution of some governing state, whether kingly, or aristocratic or even bureaucratic (professionals working full-time for the state). It belonged naturally, by the will of their Creator, with the people themselves. The new federal government with its carefully defined and limited authority would function only as the sovereign American people should empower it, either directly through the House of Representatives or indirectly through the Senate (representing the states, whose own political officials were generally elected in whole or in part by the people). Protecting and preserving the sovereignty of the people

The people's rights, of course, are hard to hang on to, as the Framers of the Constitution were well aware, having just fought a bitter battle against the English king and his armies to preserve their rights as Americans. What could possibly serve as some kind of guarantee that these rights would not be lost again, that some kind of tyranny of those who lust after political power (and find ingenious ways of justifying this lust morally) would not eventually arise in America? They were quite familiar with the failures of Athens, Rome and Israel in this regard. What could guarantee that this would not also happen to them? This is why Franklin answered the query as to what the Constitution architects had created: "A Republic ... if you can keep it." 8Note that the First Amendment makes no mention of the "separation of church and state" which has come (via Thomas Jefferson) to be understood today as meaning that traditional religion (Christianity, for the most part) may not be practiced or involved in the ever-widening realm of the nation's public domain (most notably, public schools and public grounds of any kind). Actually, the Amendment clearly meant that the state had no business whatsoever regulating the practice of religion – which it does extensively today via the federal courts – in establishing Secularism (Humanism) as the only religion allowed to be practiced in the public domain. Precisely, the Supreme Court has taken the authority to describe in detail exactly when and where religion could be practiced legally, and where it is to be prohibited from being freely exercised – in clear and total violation of the First Amendment. 9An expression that went all the way back to 1096 when Christian Crusaders headed off to the Middle East to liberate the Holy Lands. But eventually it became the proclamation of English kings as they authorized new royal rules. 10Especially

the Puritans or Congregationalists, the Scottish Presbyterians, the

Dutch Reformed, the German Reformed and French Huguenot communities in

America. The Baptists (offshoots of Calvinism) and Quakers also had

this same understanding of society and its politics. |

|

| But

all of them knew the answer to that question: their sovereign rights,

their personal freedoms, could be guaranteed by no living being, no

matter how kindly disposed he might originally be. According to their

Puritan understanding, man was by nature invariably a sinner. Given

enough opportunity, power would corrupt any human heart.

A mechanical system of checks and balances

Certainly they had been careful to build into the government a system of checks and balances which would actually use human selfishness or political greed to good effect. The system was set up so that cooperation among a number of various branches of government would be required to make the system work. And cooperation meant compromise, the necessity of having to give up the desire for total power, in order to employ any power at all. If one of the branches of government would start to assume more power for itself (a rather certain possibility) this would stir the indignation of the other branches, which out of a self-serving sense of the relative loss of their own power, would gang up on the usurper of their joint power! A very ingenious system! In God We Trust

But by no means did they rely entirely – or even mostly – on this ingenious mechanical system. They were well aware, just as Franklin had stated, that this whole enterprise would ultimately succeed or fail on one issue, and that alone: the will of God. They needed to stay closely in line with the will of God, who after all had given them the victory against royal tyranny in the first place. They needed to look to God in full trust for such protection, look to God as "In God We Trust." Otherwise nothing, not even clever mechanics, would protect them from human evil.

George Washington stated the case very clearly in the speech he addressed to the nation as he took office in 1789 as America's first president: It would be peculiarly improper to omit, in this first official act, my fervent supplication to that Almighty Being, who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States, No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the invisible hand which conducts the affairs of men more than the people of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency, We ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained.This was not mere political posturing, this reference to the all-important role that God had played in winning for America its national independence, Washington's appeal to Americans to continue to look to that same God for divine support as the nation now moved forward. his appeal to God's favor was very serious business for it rested on a Truth that recent experience had made very, very clear. This was not just religious platitude, designed by Washington to comfort the people with an assurance that he was a proper church-going Christian (which he frequently was not). This was testimony to the reality of politics that all of these quite astute practitioners of politics had come to understand – at a very deep level. The American venture would not fail, as had Athens' and Rome's and Israel's attempts at self-government, as long as it retained a very deep sense of connectedness to God and his hand in the affairs of man. Christian Realism – and the Christian Covenant

In the end what we will term as the philosophy which guided these framers of the American Constitution is "Christian Realism." This philosophy was founded on the understanding that man can be both an angel and a devil, prone to do good and prone to do evil. Man must be allowed enough opportunity to put into effect his ability to do the good, while at the same time be put under enough legal restraint to check him against his equal ability to do evil. Ultimately only God could be counted on to do the truly good. But man and God could work together, with man operating under God's judgments, inspired by an awe of God and desire to please God – yet at the same time fearful of what might happen if he did not remember to obey God. Thus this Constitution would work for American society, as long as Americans understood the rules and as long as Americans freely chose to keep this Constitution as a Covenant with God. Anything else would fail. As Christians, the Framers of the Constitution were well aware of the words of advice – and warning – that Moses gave Israel as it entered the Promised Land (the very same verses that Founding Father John Winthrop referenced in his 1630 sermon, just as the Puritans were about to embark to begin their great Puritan experiment):

|

|

|

The process of ratification

Whereas some of the states were quick to approve (ratify) the new Constitution, not everyone was completely sold on the new Constitution. As a result, it was not until June of the following year (1788) when New Hampshire, the ninth of the thirteen states voting to ratify, finally put the Constitution into full effect.11 During the debate over ratification, Anti-Federalists, such as Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry, had voiced their fears through various newspaper articles that the individual states were simply surrendering too much of the people's sovereign rights to this new central authority. What were the guarantees that this new government would not come to assume the powers of the royal government they had so recently fought to free themselves from?

Federalists were quick to take up the challenge,

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay writing replies to these

questions under the pen name Publius. Some eighty-five articles were

published by these three men, each article carefully explaining the

workings and benefits of this new Constitution, a collection of

articles which have come down to us today as the famous Federalist Papers. Madison turned some of the criticism of the Anti-Federalists on their head, pointing out that factions would form within the government, simply because of the size of the new country, but these factions would serve the useful purpose of checking each other's ambitions for power, forcing debate and clarity of thought in government, and encouraging the people to follow political developments closely rather than just letting government officials go about their business quietly out of the public sight, where tyranny might then truly develop. Hamilton, for his part, stressed how a stronger central authority would more likely attract society's natural leaders, involving them more closely in the building of a financially sound economic system, the best guarantee of a society's stability (and consequently its ability to protect personal freedom and prosperity). And thus it was that the Federalists were able to bring the country to approving this new experiment in republican government. The last days of the Confederation

The new federal Constitution was not submitted to the Congress of the old Confederation, where it probably would have faced such resistance that it would not have passed, but was sent directly to the states for their approval. Each state was invited to set up its own process of ratification, usually through a special session gathered for specifically that purpose: to approve (or reject) the new Constitution. Thus the Congress of the Confederation was left entirely out of the process that would bring its own existence to an end. However, the Confederation did perform for the new nation one final and very important service when in 1787 it set out clearly with the passing of the Northwest Ordinance the basis for designing and admitting new states into the Union. Having been accorded the right by the Treaty of Paris to develop the land west to the Mississippi as American land, the Congress had a two-fold job: 1) get the states to stop arguing over the ownership of that land and 2) instead set up in this territory, at least in the Northwest, a number of candidate-states, open to settlement and to eventual admission to the Union as full members states – as they gained a certain size of population and established their own state Constitutions. Thus it was that the Northwest Territory (today's Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and what would become the eastern portion of Minnesota) was divided originally into a number of territories or future states (ten originally, but ultimately the five-plus described above). Also plans were drawn up for the creation within these territories of towns and townships – according to a precise grid pattern where each township was defined as a square of six miles on each side, further divided into thirty-six sections of 640 acres each (one square mile). Also a section within each township was ordered by the Northwest Ordinance to be set aside for sale for the support of public education; and a public university was also to be established within each of these major states. 11Delaware,

Pennsylvania and New Jersey had quickly ratified in December of 1787

and Georgia and Connecticut followed soon after in early January of

1788. Massachusetts (narrowly) ratified in February, Maryland in April,

and South Carolina in May, before New Hampshire signed on in June.

However, Virginia followed later in that same month, and New York in

July, thus assuring the Constitution that it would have the full

support of the heavyweight states. North Carolina did not ratify until

December of that year. Rhode Island, after first voting against

ratification, finally in May of 1790 approved the Constitution. |

|

These 84 newspaper articles were written to explain the workings of the new Constitution and its political benefits ... in the effort to get the new document officially ratified by the states.

|

|

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges