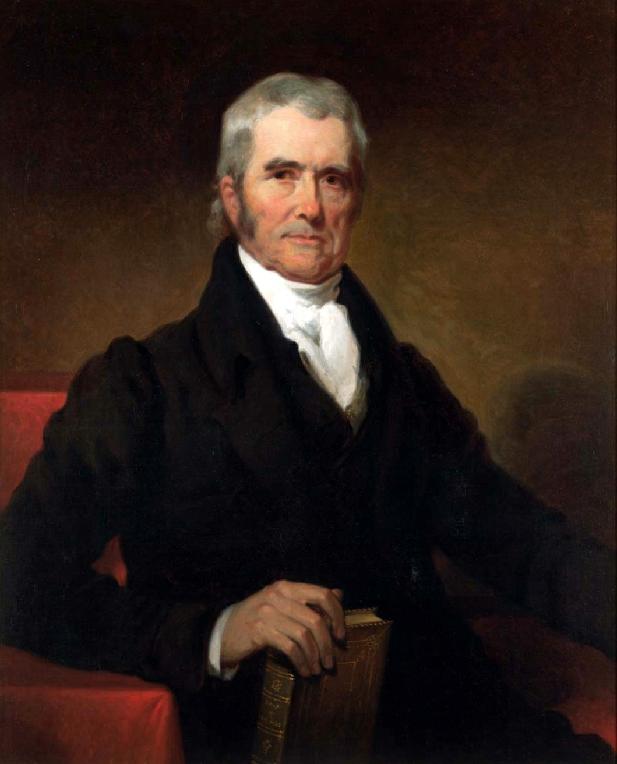

Marshall develops of the powers of the U.S. Supreme Court

One

part of the Federalist heritage that the Republicans could not undo was

the Supreme Court and its various Federalist appointees by Adams, most

notably the U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Marshall

was a strong Federalist, unlike most of the rest of his fellow

Virginians, who tended to be Jeffersonian Republicans. He had declined

Washington's offers of being a part of his Administration (turning down

the offer first to be the nation's attorney general and then ambassador

to France) and even Adams' first attempt to nominate him to the Supreme

Court. But considered one of the most brilliant lawyers of his days, he

was again nominated to the Supreme Court as its chief justice in Adam's

frantic effort to put Federalists in office before the Republicans took

control of both houses of Congress and the White House in early 1801.

This time Marshall accepted the offer.

Jefferson and the Republicans were furious about

the Federalist judiciary, especially by the way the

Federalist-dominated courts had treated Republicans under the ill-fated

Alien and Sedition Acts, and were determined to clean the courts of the

midnight judges. Jefferson's secretary of state, Madison, refused to

sign the commission of the Federalist William Marbury, a commission

appointing Marbury as justice of the peace in Washington D.C. Marbury

sued Madison, bringing before Marshall's Supreme Court the famous case

of Marbury v. Madison (1803).

But ultimately Marbury lost the case, due to

Marshall's questioning about who exactly had the right to bring this

case before the Supreme Court. In theory Marbury had a right to his

appointment. But it was done under a law, the Judiciary Act of 1789,

that supposedly gave Marbury that right to bring the case directly to

the Supreme Court. But Marshall argued that the Constitution itself

permits original jurisdiction for the Supreme Court only to foreign

policy issues or state issues. Marbury's case involved neither factor,

despite what the 1789 law seemed to authorize. In fact, the 1789 law of

Congress was invalid, because it was "unconstitutional." Thus Marbury

had no right under the Constitution to proceed as he had.

In one short stroke, Marshall had just accorded to

the Supreme Court the power to decide what laws of Congress were and

were not constitutional. Though the Constitution itself mentioned no

such power belonging to the Supreme Court, Marshall's decision was not

contested. At the time, it seemed like a win to the Republicans. But

the Republicans did not see that the principle underlying Marshall's

decision laid the groundwork for the Supreme Court to continue to move

down this road of making itself the ultimate decider in the land as to

what was law and what was not, or worse, how the law might be better

interpreted by progressive judges.

For the next three decades Marshall and the

Supreme Court rendered various decisions which further strengthened not

only the voice of the Supreme Court, but also the supremacy of the

Washington, D.C., government over the various state governments. For

instance, in the Fletcher v. Peck (1810) decision, Marshall's

Supreme Court affirmed that federal authority took precedence over the

laws of the individual states. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), his court denied the rights of the states to tax federal agencies (in this case the Bank of the U.S.). In Cohens v. Virginia (1821) Marshall declared that the Supreme Court had review powers over the decisions of the state courts.

The larger implications of Marshall's legal inventiveness

In his 34 years of Supreme Court service (1801-1835), he turned this

panel of judges into something more akin to true legislators, revising

the law of the land at will. Not only did his court pass judgment

on legal contests that inevitably arise from applying the law in

particular cases (the traditional role of English judges) ... he

actually went well beyond that in deciding how such laws should be

interpreted or even be reinterpreted ... or even be set aside as

"unconstitutional" – according to his own personal Federalist political

instincts. But these could be almost anything he deemed as

"reasonable." Thus slowly he was reshaping Constitutional Law so

as to make it conform to the logic or reason of a small group of

jurists who happened to be sitting on the bench – actually only a

simple majority among them being required for a wide-sweeping decision.

And there was no built-in "check" on such enormous power.

Justices, once appointed, served for life – not subject to any

subsequent elections or renewals of their appointments by the world

other than their deaths (or voluntary retirement) itself. Tragically,

the Framers of the Constitution did not see this power-expansion coming.

No such power as the Supreme Court assumed for itself was actually

ever assigned by the Constitution. And the English political tradition

that the Framers thought they were working with had no such grants of

political power assigned to their judges. This political expansion was

all a result of Marshall's personal creativity.

Wow! Lawyers in black robes! But what else did anyone think was

likely to occur if nothing was said or noticed at the time.

In any case, this single judicial appointment would establish a

political path that would slowly make the Supreme Court, not Congress,

the supreme legislative body of the land

Jefferson begins the reign of the Democratic-Republicans

Jefferson begins the reign of the Democratic-Republicans The war with the Barbary pirates at "the shores of Tripoli"

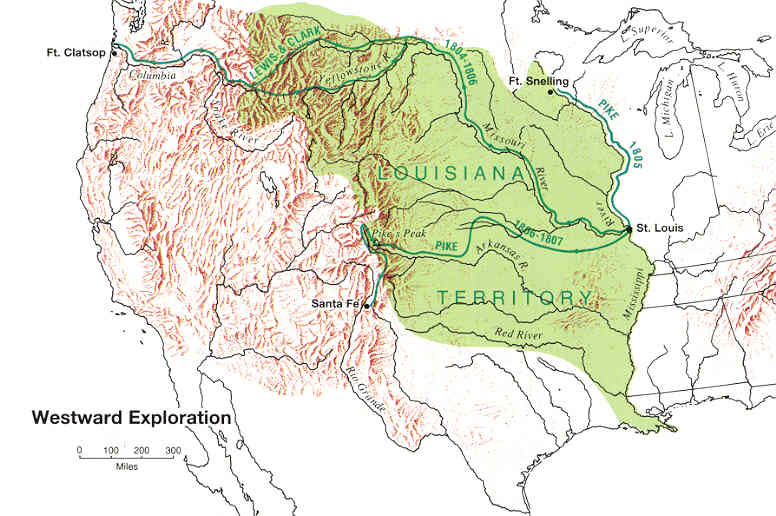

The war with the Barbary pirates at "the shores of Tripoli" The Louisiana Purchase ... and the follow-up expeditions

The Louisiana Purchase ... and the follow-up expeditions Hamilton vs. Burr

Hamilton vs. Burr  Marshall develops considerably the powers of the Supreme Court

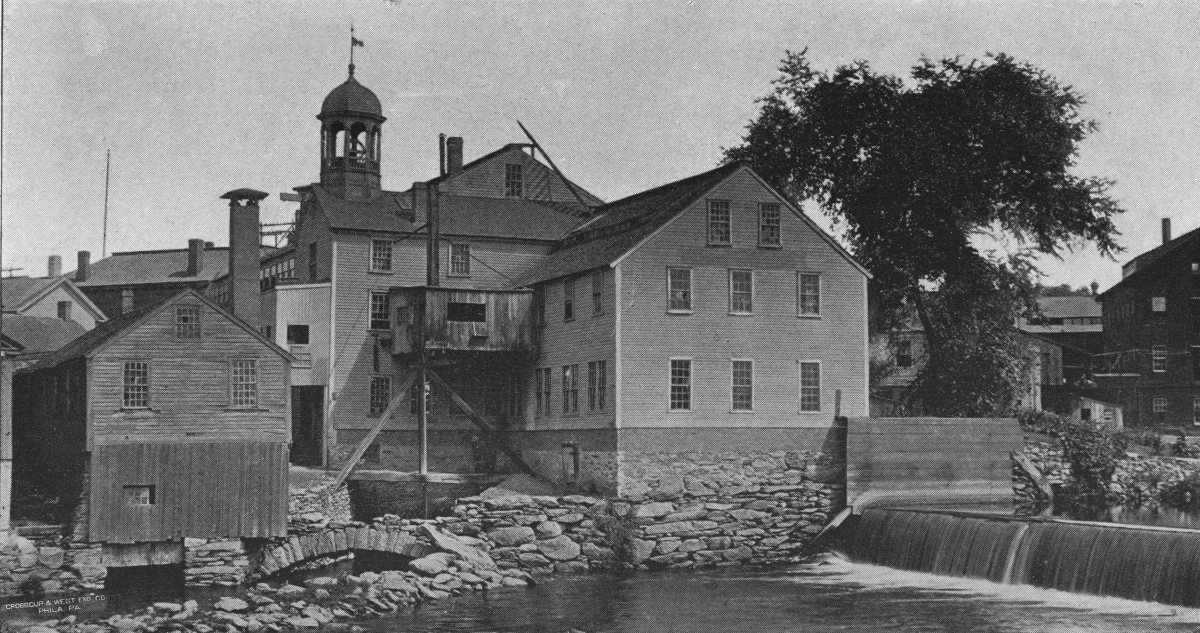

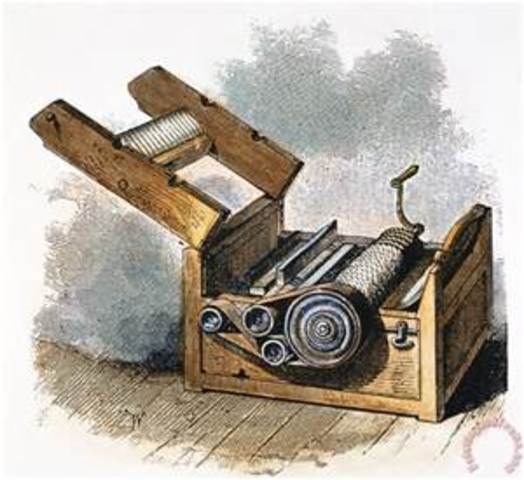

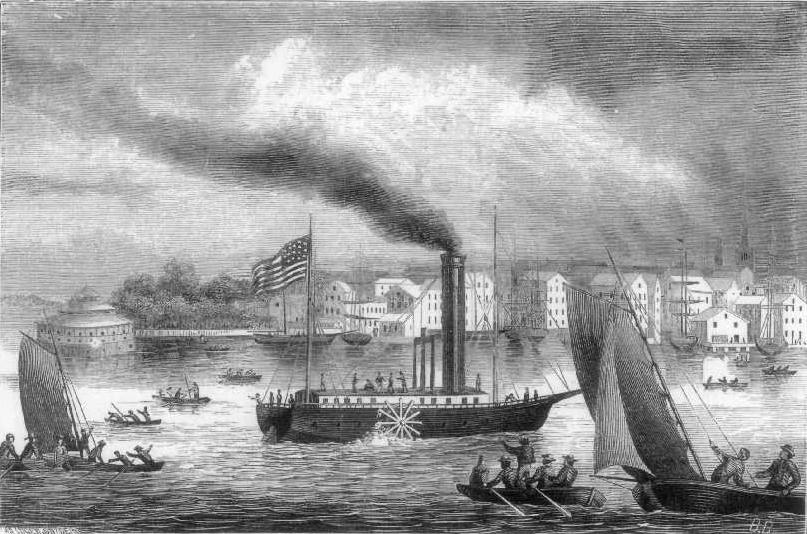

Marshall develops considerably the powers of the Supreme Court America is introduced to the Industrial Revolution

America is introduced to the Industrial Revolution

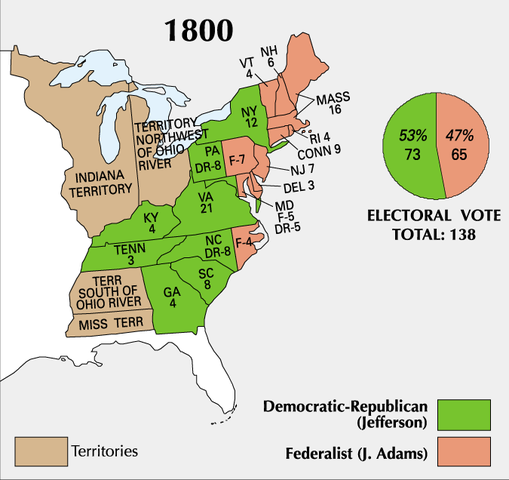

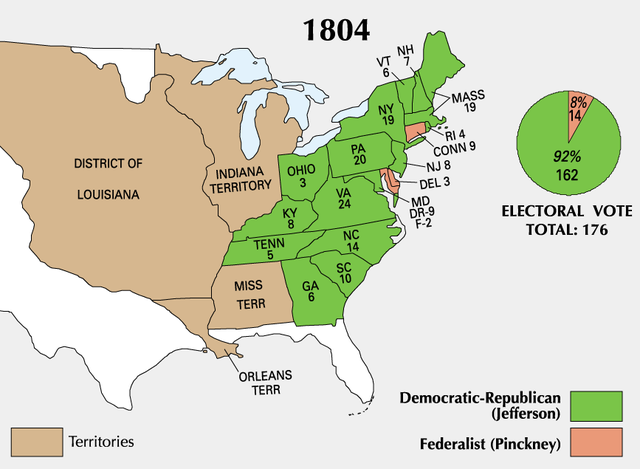

Presidential election of

1800 – electoral votes

Presidential election of

1800 – electoral votes

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges