|

|

Americans and Europeans to Texas Americans and Europeans to Texas  The move to Texas independence The move to Texas independence The Battle of the Alamo ... and the massacre at Goliad The Battle of the Alamo ... and the massacre at Goliad Texian victory at San Jacinto (April 1836) Texian victory at San Jacinto (April 1836)  The debate over Texas joining the Union (1837-1845) The debate over Texas joining the Union (1837-1845)The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 249-252. |

|

|

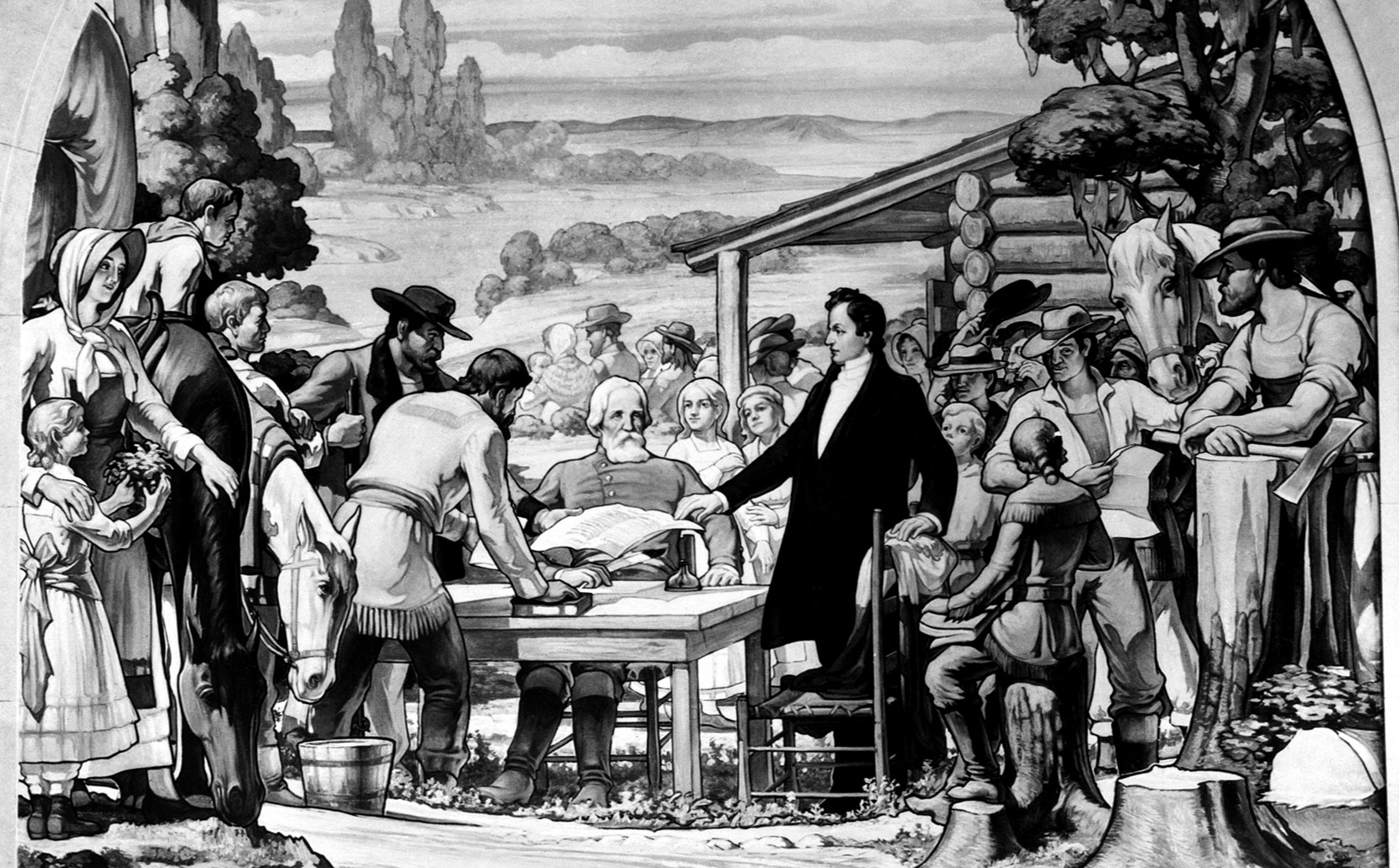

The Comanche Indians were a constant problem for the Hispanic settlers and the decision was made in 1824 to encourage European and Americans to settle in the area. This had already been happening on a small scale – as in the case of the empresario, Stephen F. Austin, bringing some 300 Americans to settle along the Brazos River in 1822. Then with this decision a large number of others, mostly Americans, were settled in Texas under a number of similar empresarios. Finally the influx of Americans was so overwhelming in numbers1 that in 1830 Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante closed the borders to further immigration. But the American immigrants, sensing the Mexican effort to isolate them, fought back – at the same time that a revolt against the Mexican president was taking place in the Mexican capital. Taking advantage of the political chaos and supporting the party of Mexican Federalists fighting the Mexican Centralists, Texans gathered at the Convention of 1832 to discuss the option of independent statehood. The spirit of independence was thus birthed in Texas. 1At

the beginning of the migration in 1825 there were only about 3,500

settlers in Texas, mostly Hispanic. Less than ten years later that

figure was over ten times that size, about 80 percent of them

Americans, with a substantial number of slaves among them.

|

|

|

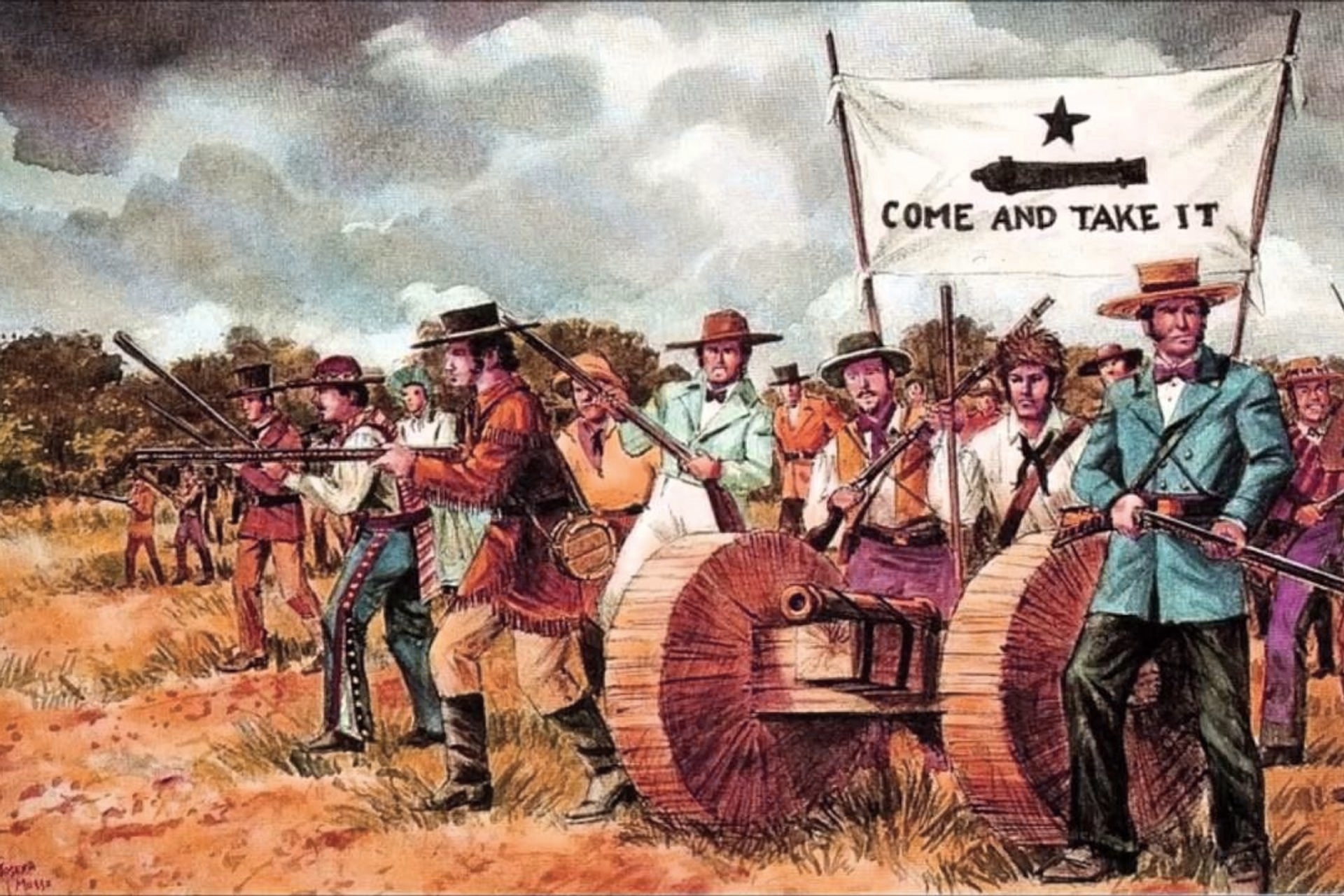

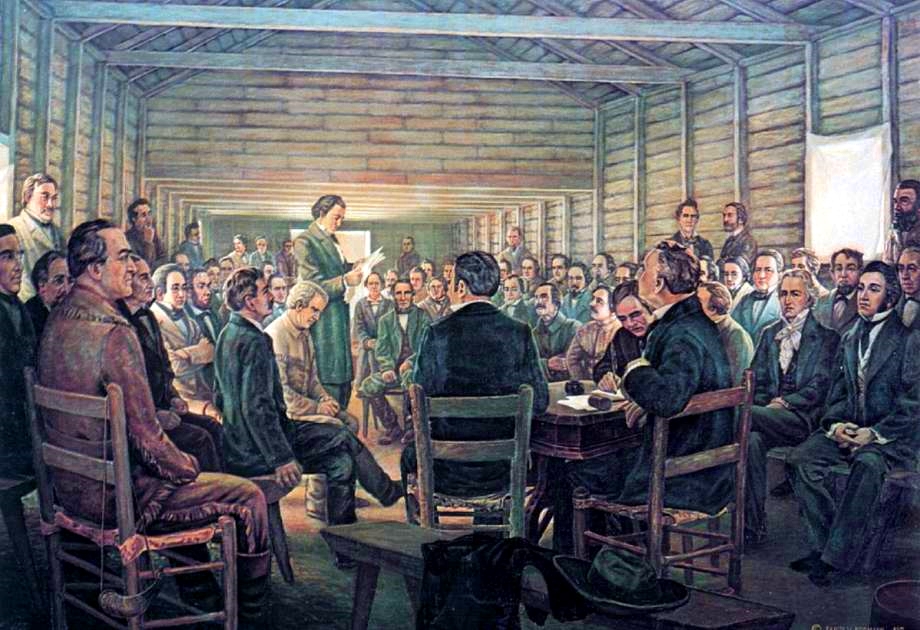

The Battle of Gonzales and the Consultation (1835)

When in 1835 a small Mexican military contingent was sent north to crush this spirit, a similarly small group of Texans fought the Mexicans to a standoff at the Battle of Gonzales, merely strengthening the desire of the Texans to achieve independence. They gathered that same year (The Consultation), declaring their reasons for seeking independence and setting up a provisional government and General Council. They also established a Texas army under Sam Houston But political controversy immediately plagued the new government, which collapsed in early 1836. However, another gathering that spring produced quickly a formal Declaration of Independence (March 2nd, 1836) and the announcement of the creation of the Republic of Texas.

|

|

|

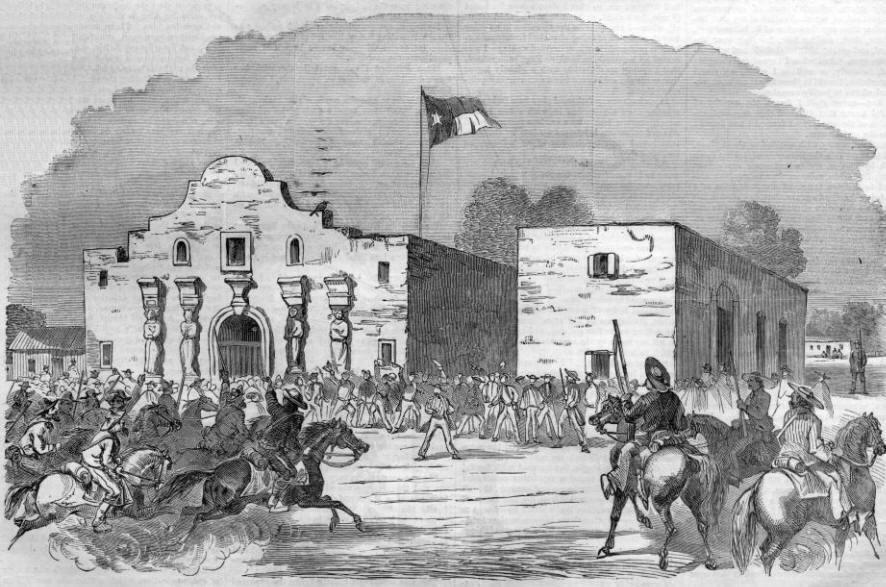

At the same time, the new Mexican president (and military caudillo or strongman), Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, had already headed north with the intention of crushing this Texas rebellion. Santa Anna's army2 surrounded the Alamo Mission near San Antonio and finally, after a siege of almost two weeks, overwhelmed the approximately 185 defenders (March 6), killing all of them to the last man. But in fact it was quite an expensive victory, costing Santa Anna the loss of 400 to 6003 of his army in dead and wounded. At about the same time another large Mexican Army began to move north from Matamoros, overwhelming small Texas units as they went. In mid-March a larger Texas unit confronted the Mexicans in three days of fighting. But the Texans ran out of ammunition and were surrounded and forced to surrender as they attempted a retreat. The Texans were marched back to Fort Defiance in Goliad. Then, under the orders of Santa Anna, the Mexican troops proceeded to massacre over 300 of these prisoners (March 27). But rather than breaking the spirit of the Texans, the event merely steeled their determination to secure Texas independence at all costs. 2The exact size of the Mexican army and the portion actually involved in the final assault on the Alamo are not known, though figures vary from 1,800 all the way up to 6,000. 3Some estimates are much higher ... but are hard to confirm because of the political implications of those numbers at the time.

|

|

|

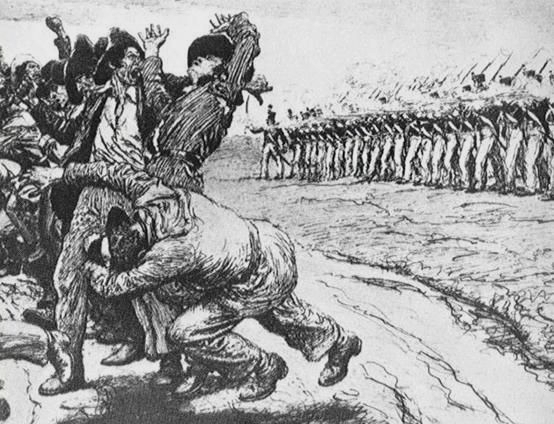

The next month Sam Houston and his Texas army

joined battle with Santa Anna at San Jacinto. A Texan surprise attack

on a wearied Mexican army and a twenty-minute battle turned out to be a

disaster for the Mexicans. They tried to flee but were simply hunted

down and killed on the spot, to the cries of "Remember the Alamo" and

"Remember Goliad!" (some 600+ Mexican soldiers were killed this way).

And Santa Anna was captured, disguised as a servant in an attempt to

escape. Amazingly, only eleven Texans died in the battle.

|

|

|

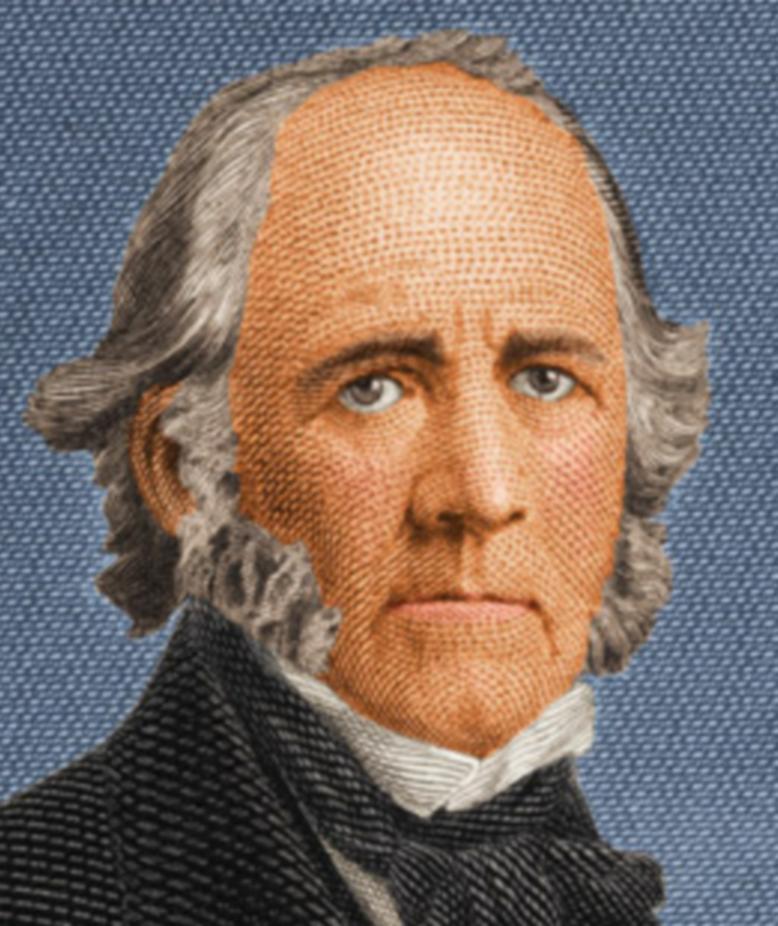

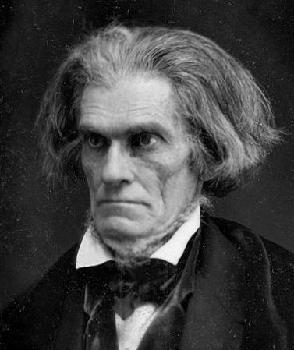

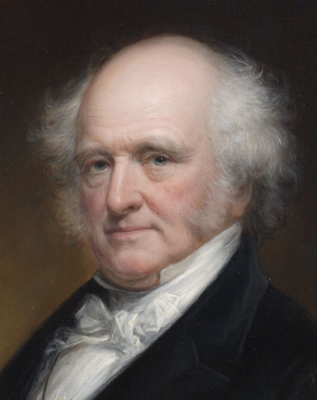

Almost immediately (1837) a split occurred within the leadership of the new Texas Republic between those wishing to retain and expand Texas as an independent republic (possibly extending its borders all the way to the Pacific Ocean) and those who wanted to see Texas annexed as a new state joining the U.S. The debate was finally decided in favor of the annexation group when Mexico sent troops back up into Texas and had to be fought off with much difficulty. This seemed to establish in Texan minds the importance of being closely connected to the greater power of the U.S. But Texas allowed slavery, stirring debate within the United States itself as to whether or not Texas ought to be admitted as a new (slave) state. President Van Buren did not want the slave issue to work its political damage at a time when he was struggling with the economic Panic of 1837 and so he tried to hold off the issue of Texas admission throughout his entire four-year tenure as president. Also he did not want to find the country at war with Mexico – which had never accepted the idea of the independence of Texas. But he faced a lot of adversity from Southerners, especially from Calhoun who was making it an issue of the South's willingness to stay in the Union if Texas were not admitted. But opposing Calhoun was John Quincy Adams, who had returned to Washington after his presidency to become a very powerful voice in the House of Representatives, and who spoke for three weeks in opposition to the admission of Texas.

|

John Quincy Adams (opposed) / John C. Calhoun (insistent on entry) President Van Buren (attempting to avoid the decision) |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges