|

|

The 1844 elections The 1844 elections The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) The moral impact of the Mexican-American War The moral impact of the Mexican-American WarThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 253-259. |

|

|

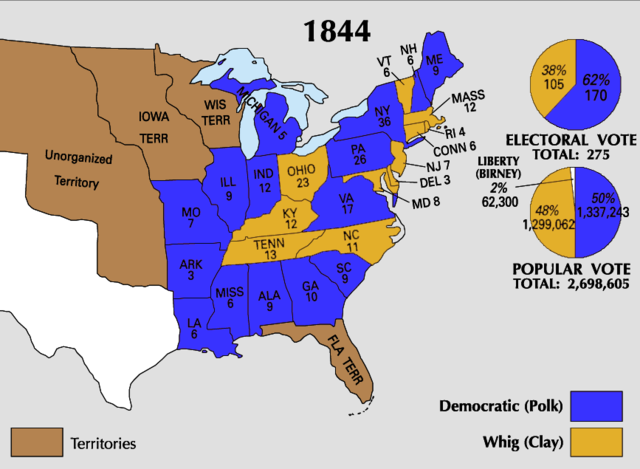

The 1844 elections: Clay vs. Polk, vs. Birney.

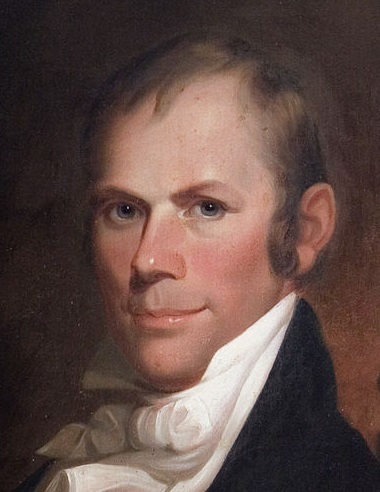

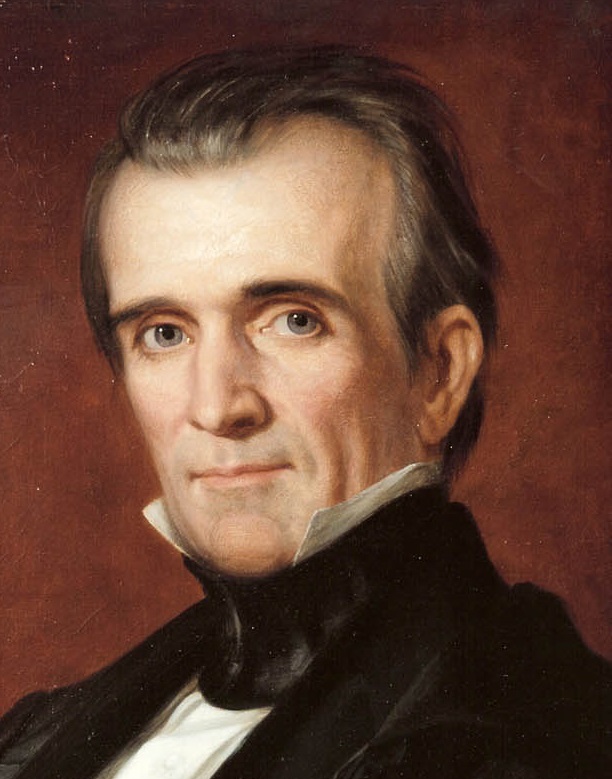

In the 1844 elections, the Whig nominee Clay found himself up against the Democrat (Tennessean) James Polk. President Van Buren had alienated so many within his own Democratic Party that the party's presidential nomination ultimately had gone to Polk, something of a dark horse that had not been one of the early frontrunners in the party. Polk subsequently ran his campaign on the promise that if elected he would admit both Texas and Free-Soil (no slavery allowed) Oregon as new states, thus offsetting some of the northern opposition to the admission of Texas as a slave state. Clay, his third time as a presidential candidate, ran on the typical Whig platform of Clay's own American System: protective tariffs to promote American industry, a strong central bank, and the building of the commercial infrastructure of canals and roads. These all tended to favor the conservative interests of the up-East financial-industrial class, and undercut his support among Westerners and Southerners. But a "third-party-spoiler," the Liberal Party's James Birney, was also running, drawing support away from those who otherwise would have voted for Clay. This would prove ruinous for Clay. So it was that Polk handily won the electoral vote, including even a large number of northern states.

|

|

|

The admission of Texas to the Union

But as a lame-duck president, Tyler, sensing that the election had served as a referendum strongly supportive of the admission of Texas as a new state, moved ahead in his last days in office as president and proposed to Congress a resolution opening Texas to membership in the Union. This was the final blow in undercutting his Whig political base, causing the president to be expelled from his own Whig party! The Whigs fought the annexation with all the strength they could muster. John Quincy Adams, who as a strong anti-slavery voice in the House of Representatives had opposed bitterly the admission of Texas as a new slave state, voiced this move as being a devastating calamity for the Union. But like the Federalists before them, the Whigs were up against a growing Manifest Destiny fever which seized the country. Remembering the fate of the Federalists, they voiced their opposition carefully. But Whig opposition would not be enough to stop the entrance into the Union of another, quite large, slave state. Ultimately Tyler succeeded in getting Congress to authorize the annexation of Texas, not by a treaty requiring a 2/3rds vote for Senate approval (which would not have been possible due to the strong Whig opposition) but instead by a mere joint resolution of both houses of Congress, which required only a simple majority in both houses! Finally the resolution providing for the annexation of Texas was signed into law by Tyler on his last day in office. And his presidential successor, James Polk, would see the annexation completed when the huge slave state Texas formally accepted the invitation to join the United States in December of 1845 as its 28th state. Steps toward the Mexican-American War.

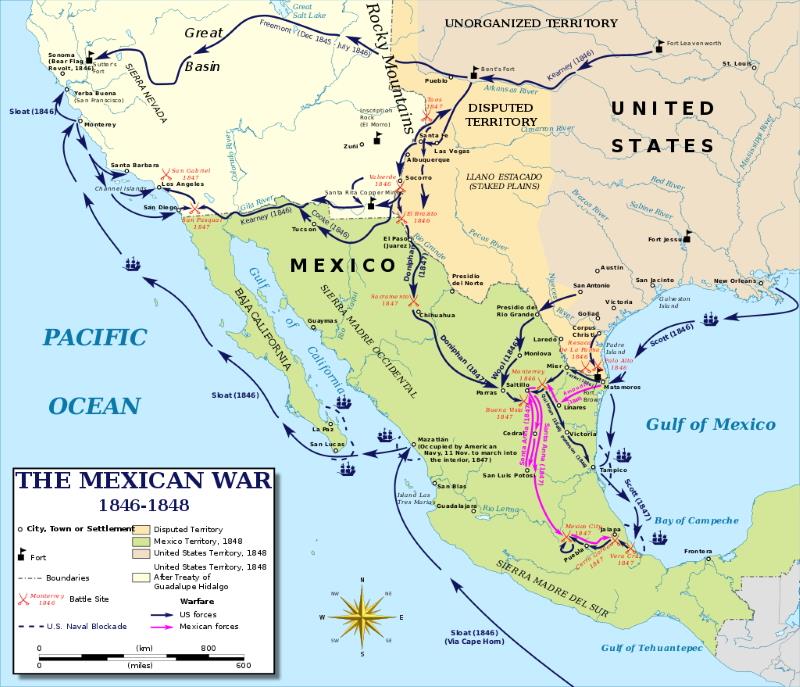

Mexico had made it clear that it would never accept the loss of its Texas province, particularly if it were then absorbed into the United States. Then when the discussions between the Republic of Texas and the United States started referencing as Texas's southern border with Mexico not the Nueces River but the Rio Grande – much further south and thus deeper into Mexico – the Mexicans were outraged. In many ways the new president, James Polk, was something of another Andrew Jackson: a strong personality who was unafraid of stepping on toes in order to get done exactly what he wanted. He also knew that Mexico was furious enough over the admission of Texas to the Union that war could easily develop between the two nations. He was prepared for that possibility as well. But also Polk was by every instinct the lawyer who believed that it was better to work out a deal with litigants than go to court. By those same instincts he was hoping he could work out a deal with Mexico, perhaps purchase his way to a settlement. He was prepared to offer Mexico millions in assistance and even in purchase of Western territory itself. He knew of course that the Mexicans themselves were fired up for war and wanted satisfaction for their bruised sense of honor. Money would not restore that sense of honor. Americans themselves were also getting fired up for war. Thus war was likely. But Polk wanted to make sure that if and when it occurred, it would take place on America's terms, not Mexico's. The situation was complicated further by the fact that relations between the Americans and the British were quite unresolved in the far West. The British claimed Canadian territory along the Pacific Coast deep into the Oregon region. There were rumors circulating that the British were interested even in extending their imperial hold all the way into California and were thinking about purchasing sparsely inhabited California from Mexico. The Mexicans were possibly considering this as preferable to having as northern neighbors more Americans, who also were eying that land. Thus some kind of Mexican-English relationship was possibly building which would have weakened the American hand considerably in any war with Mexico. Furthermore, though humiliated in the Texas war of Independence, the Mexican military was considered to be no joke of an army. European military experts in fact expected that in any direct military confrontation with America, the Mexican army, huge and well disciplined, would make quick work of the motley crew of American militia and the rather small national army. Indeed, many were certain that the superior Mexican army would quickly roll back the Americans all the way to Washington, D.C. Seeing the war clouds darken, in mid–1845 Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to move American troops into Texas and position them on the Nueces River, waiting to see what might develop. He also sent a small military group (sixty men) of explorers under General John Frémont to Oregon through California (still part of Mexico), whose larger purpose was a mystery to the Mexicans. Highly suspicious of Frémont, the Mexicans ordered him out of California. Then in early 1846 Polk sent an offer to Mexico to purchase California and New Mexico. He also in April ordered an American warship to move into the San Francisco Bay to protect Americans living in California. Meanwhile Mexico itself was undergoing tremendous political turmoil (4 different individuals succeeded each other in the Mexican presidency in 1846, 6 in the war ministry and 16 in the finance ministry). A big part of the problem was that the Mexican leaders themselves could not agree on what to do in the face of the growing possibility of war with America. Centralists demanded war; Federalists requested negotiations. Back and forth the controversy swayed, until the military party of Centralists seemed to have grabbed firm control. War is declared (May 11, 1846).

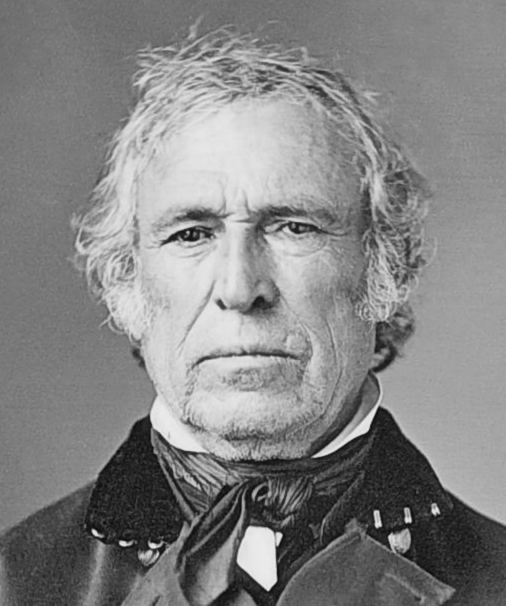

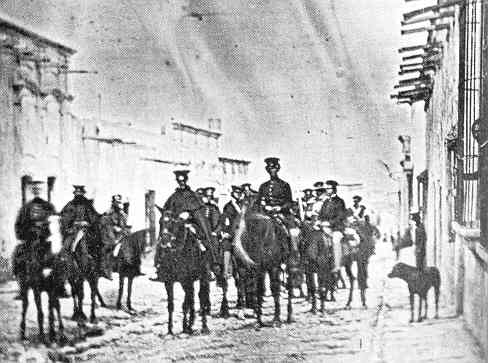

Polk then ordered Taylor to move his troops all the way to the Rio Grande, where Taylor constructed a fort. For the Mexicans this was the final insult, as they still claimed the land south of the Nueces River and north of the Rio Grande as theirs. In late April of 1846 they issued a declaration of intent to fight a defensive war and sent a detachment of 2,000 Mexican soldiers to expel the Americans from what they considered Mexican territory. In the process, the Mexicans overwhelmed a small patrol of seventy American soldiers in the disputed territory, killing sixteen of the Americans. On May 11th, claiming that Mexico had killed American soldiers on American soil (for that was the American view on the matter of the territorial boundary), Polk asked Congress for a declaration of war. The Democrat-dominated Congress obliged him – though the Whigs, seeing this as playing to the advantage of the Southern slave states, were highly opposed to this decision. Action in Texas actually had taken place even before the American declaration of War. Mexican and American armies had met at the Rio Grande earlier in May, and the results were disastrous for the Mexicans. From then on, the southern front in the war would be fought in Mexico, not Texas. California was next to become the scene of battle. In June of 1846 Frémont returned to California to openly invite a revolt (the Bear Flag Revolt) of Americans in Sonoma (northern California). This all looked quite similar in character to the Texas rebellion ten years earlier, except that the Californians moved immediately to replace the California Bear Flag with the American flag. Frémont's army moved south to capture Los Angeles, and was joined by the army of American General Stephen Kearny, moving in from the East across the vast southwest desert, who easily took San Diego. By January of the following year (1847) the Mexicans were forced to surrender their claim to California. England, meanwhile, had elected to stay out of the conflict. In the meantime, Taylor began to advance his troops into Mexico from the northeast. His troops were a wild collection of volunteers, undisciplined, and at times functioning more like a drunken mob than an army (raping and pillaging as they went). It took considerable effort for Taylor to finally be able to shape his gringos1 into a disciplined army. Taylor's first major encounter with the

Mexicans was at the city of Monterey (September 1846) where his army,

unused to urban warfare, ran into stiff resistance from Monterey's

troops and citizens. Ultimately to achieve a win, Taylor had to resort

to an armistice allowing the Mexican soldiers to leave the city

peacefully. Technically this marked an American victory. But Polk was

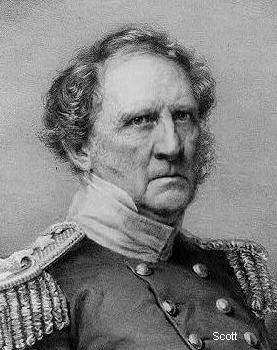

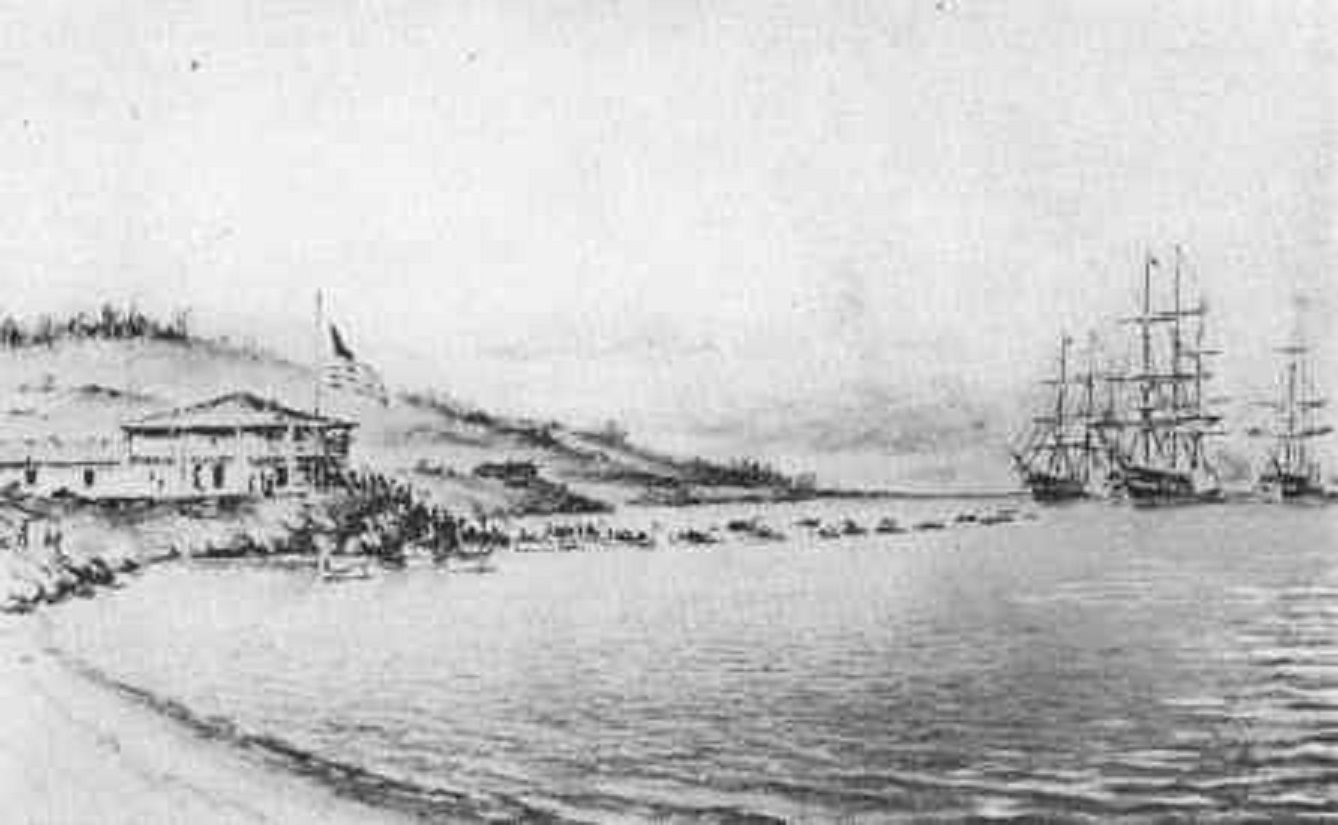

furious about such a weak showing by Taylor. During all of this confusion the Comanche and Apache Indians had been conducting raids on the Mexicans. Thus as American soldiers advanced from the northwest toward Mexico City, they found the countryside deserted and the towns unwilling to resist the advancing Americans. At the same time, Americans under naval Commodore Matthew Perry were fighting the Mexicans along the Mexican shores and tributary rivers of the Gulf of Mexico, inflicting humiliating defeats on the Mexicans as they went. Polk now turned to General Winfield Scott (working closely with Perry) to lead an assault in March of 1847 on the Gulf of Mexico coastal town of Vera Cruz, to reduce the walls protecting the city in preparation for a massive amphibious landing of American troops whose ultimate destination would be Mexico City. Seriously outnumbered by this attacking American force, the Mexicans were only able to hold out a dozen days before having to surrender Vera Cruz to their American attackers. The Americans then headed west to Mexico City and, after overcoming stiff resistance to the north of the city at Chapultepec (including the brave fighting of the Mexican students at the military academy located there), were able to enter the city in mid-September. Santa Anna was overthrown and fled the country. The Americans were now in total control of the Mexican political heartland.3 The question then arose: what to do with Mexico? Some political voices speculated that the Mexicans themselves might greet annexation to the United States gladly. The Whigs were however strongly opposed to the annexation of Mexican territory, fearing it would only expand the political weight of the pro-slavery portion of the nation. But in fact, neither the Mexicans nor most Americans had any interest themselves in such a union. 1There is some dispute about the origins of the term gringo. Some claim that it originated from the song that the Americans sang, "Green Grow the Lilacs," as they marched through Mexico! 2Taylor would make much of this victory in his successful bid for the U.S. presidency in 1848. 3Marines

were put on guard duty at the Mexican National Palace, the "Halls of

Montezuma," completing the opening line of the Marine's hymn: "From the

Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli..." [from Mexico City to

the shores of the Barbary Pirates].

|

|

|

Many of the Whigs of the American North had viewed the Mexican-American War as little more than an effort of the South to strengthen its political position in Congress by adding newly conquered territories, and thus subsequently future states, to the pro-slavery roster. Most notable in their opposition to the Mexican-American War in this regard had been Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. They employed every argument possible concerning the moral degeneracy of the imperialism America had inflicted on its Mexican neighbors. However most Whigs certainly encouraged the idea of American expansion westward – as long as any newly acquired territories remained in the Free-Soil category. Then in August of 1846, during the debate approving the $2 million in appropriations underwriting potential negotiations with Mexico (which it was hoped at the time might end the war) the gauntlet was thrown down in Congress by Representative David Wilmot. He wanted attached to the appropriations bill the proviso that would ban slavery in any of the lands that the Mexicans might turn over to the Americans (the Mexican Cession) as a result of a much hoped-for negotiated peace settlement. The bill passed in the House, but failed in the Senate when Congress dismissed without considering the resolution. When Polk later that year made another request for funds to negotiate a peace settlement with Mexico the Wilmot Proviso was reintroduced and hotly debated. However as debate developed, an additional demand was added the following year that the prohibition of slavery be extended to any new territory acquired by the United States. Tempers were now hot. Then Alabama Representatives proposed a

counter-resolution which would leave the slavery issue to the

individual territories to decide (building on the philosophy of the

sovereignty of the states, or states' rights). The measure failed to

pass, but united the Southern representatives into a strong regional

bond, one that would build and become the main political identifier

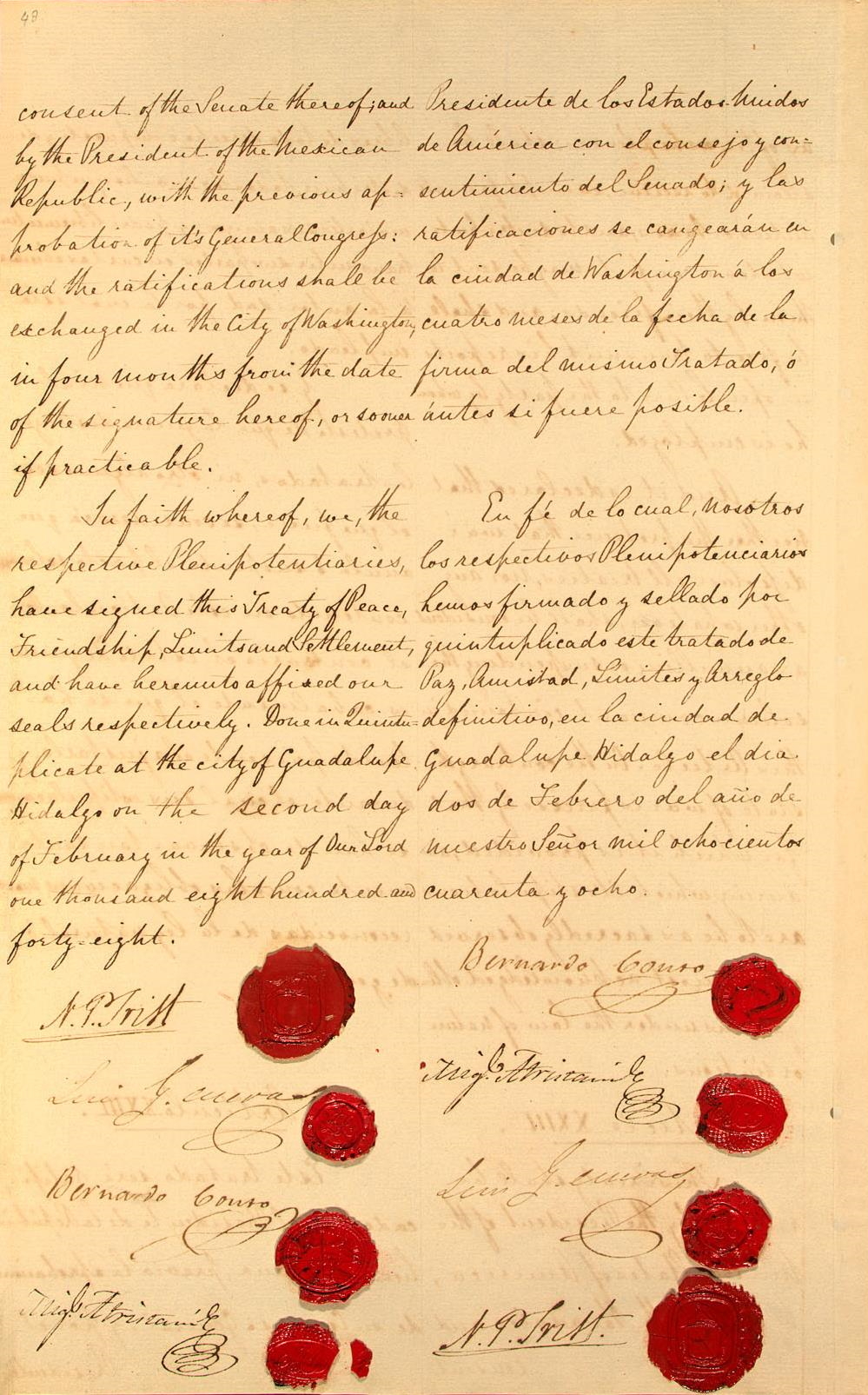

among the members of Congress. America's major political division now followed not the more traditional Whig/Democratic Party lines, but ominously North/South regional lines. The parties themselves were splitting into North-South factions, especially as the Wilmot Proviso kept getting introduced time and again in the North's hope of finally forcing the end of slavery on the South. Finally, with the American military

victory in Mexico City, negotiations got underway in January of 1848 at

the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and within a month the two sides agreed

on terms: Mexico would receive $15 million in payment from America for

the acquisition of California, Texas to the Rio Grande, and the

territory in between (which would eventually become New Mexico, Arizona

and Utah.) John Quincy Adams' death, and the finalizing of the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty When the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification in February, the Whigs were bitterly opposed to any affirmation of the Mexican-American War and its outcome because of the blatant imperialism involved. Even with the revealing of the generous terms offered to and accepted by Mexico in the negotiations of 1848, a storm erupted. Certainly the generosity undercut some of the imperialist argument, though others were appalled at just that generosity. But mostly the eruption occurred over the idea of a number of potentially new states in the Southwest being lined up for statehood and how this would tip the balance in the growing North-South split over slavery. Leading the attack on the treaty was the distinguished Whig senator from Massachusetts, Daniel Webster, the Great Orator. Then in the middle of discussions going on in the House, John Quincy Adams was felled by a heart attack, bringing the proceedings to a halt over the next days as the nation stood watch over the last man with personal connections with the Republic's Founding Fathers, and who himself had come to grow greatly in the esteem of his Congressional colleagues because of his cool wit and sharp insights. When he died on the 23rd (of February) the nation mourned. The effect was to sober the proceedings in the Senate, which in early March finally moved to approve the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty, 38–14. The size of the financial award offered to Mexico for the loss of its territory still caused some to question exactly who it was that had won, and who had exactly lost the war! But it was a wise move, giving a degree of fairness to the war's outcome, because Mexico might otherwise have continued to harbor a deep resentment over a total loss – such that Mexico would have been tempted to renew the war at a time when America was less able to fight, as would have been the case when America fell into its savage Civil War thirteen years later.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges