|

|

The Abolitionist Movement The Abolitionist Movement The election of 1848 The election of 1848The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 261-266. |

|

|

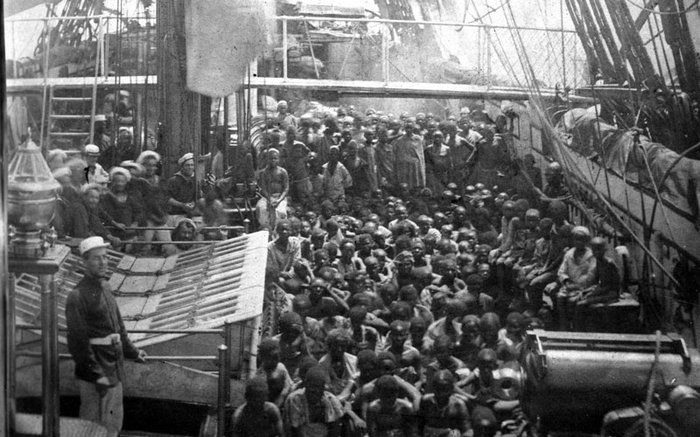

In the meantime, American culture was splitting

ever more deeply over this persistent question about Americans holding

slaves. There was no way that the problem was going to simply go away

on its own or just be avoided, as many Americans had earlier held the

hope that this might be possible. But high-sounding principle was

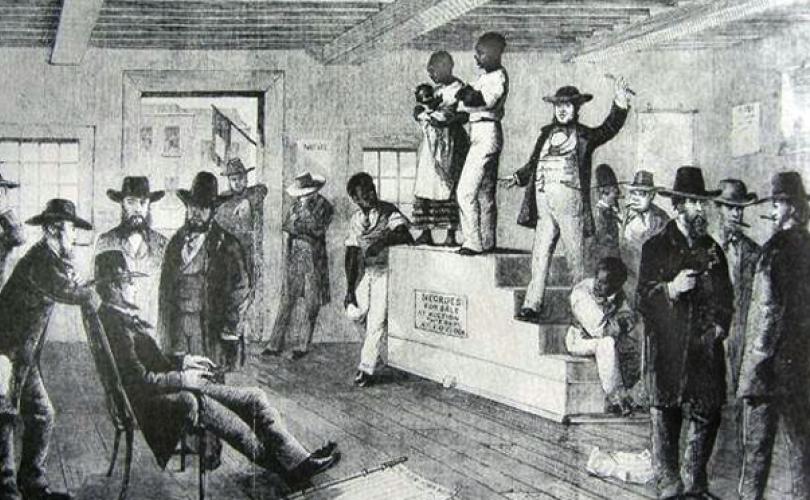

easier to achieve than actual plans of action.1 Unfortunately, such a large part of American culture (especially in the South and parts of the West) was built on ideals requiring the labor services, voluntary or involuntary, of other people. To undo such a social system was to destroy the cultural ideals of economic and social success themselves. Christian Abolitionists

But there also was no way that the spirit of Puritan Protestantism widespread in the North could ever come to tolerate intellectually and emotionally this behavior in the land of freedom. Slavery violated every Christian sensibility of the Northerners, to a point that some in the North grew increasingly impatient at the willingness of even their own Northern politicians to tolerate or ignore this stain, this sin corrupting the soul of the great American nation. Americans were understood to be a Covenant people called to display to the world the glories of living as Christ's people, to be a light spreading hope into the darkness of the surrounding world. Surely slavery made a mockery of this Covenant. Some felt very strongly that God would curse the nation for breaking this Covenant that their forefathers had agreed to two centuries earlier. And the Republic that had been put into place only a few generations back, a Republic dedicated to the high calling of being a light to the nations, would fail ... fail miserably. Thus the institution of slavery had to be abolished immediately. And so it was that those who advocated such action came to be called Abolitionists. Abolitionism and the Second Great Awakening

In fact, many Abolitionists saw in slavery the seeds of certain destruction of the American people and society, by the hand of God no less. Indeed, the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which continued to burn forward through the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s, had made slavery its main hot-button issue. Preachers, newspapermen, self-appointed social reformers and even a small handful of congressmen saw this issue intimately tied up with how God was looking in judgment at his Covenant people. America could not afford to lose its soul over this issue. In general however, aggressive Abolitionists were not widely popular, not even in the North at first. They were viewed as being dangerously disruptive of the good order of the Republic. Those who viewed themselves as being of a wiser nature tended to presume that the good moral sense of Americans would eventually work this problem out. Thus it was in 1836 that Congress had placed its gag rule on any further discussion of the slavery issue. Nonetheless, the issue was a big part of what would go on to divide the New School and Old School Presbyterians in the late 1830s, the division tending to follow North-South lines. Likewise, in 1845, the Baptists also split quite permanently along North-South lines over the matter. Europe's example

Then also there was the fact that the English had already set the noble example in 1807 by abolishing slavery within England and then in 1833 by extending abolition to the entire British Empire. France had outlawed slavery as far back as 1794 during the French Republican Revolution (though Napoleon had reintroduced the practice somewhat after 1804) and in 1848 France made the move to abolish slavery throughout all of its colonies. Thus also to the American Humanists, America's failure to follow the moral example of England and France brought unbearable shame to America as the supposed model of Enlightened Republicanism. Most American supporters of freedom for the slaves advocated a gradual process of emancipation. They considered this to be the more responsible solution to the problem. Others supported the idea of sending Blacks, both free or slave, back to Africa where it was supposed there would be a more natural fit for them. Thus Liberia had been established in 1820 by President Monroe (and thus Liberia's capital Monrovia) as a resettlement colony on the West coast of Africa. Abolitionist voices

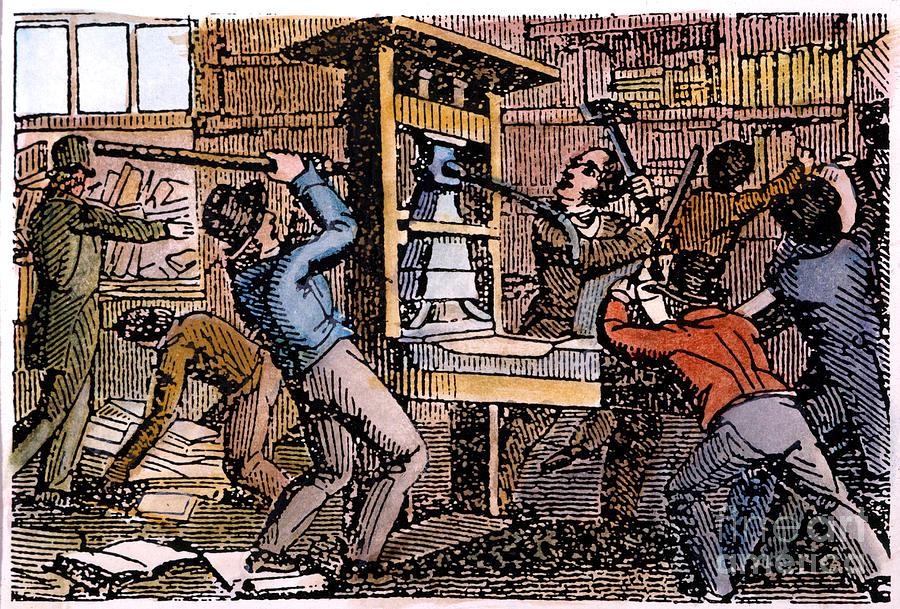

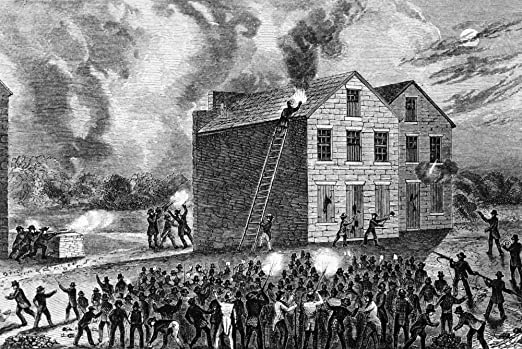

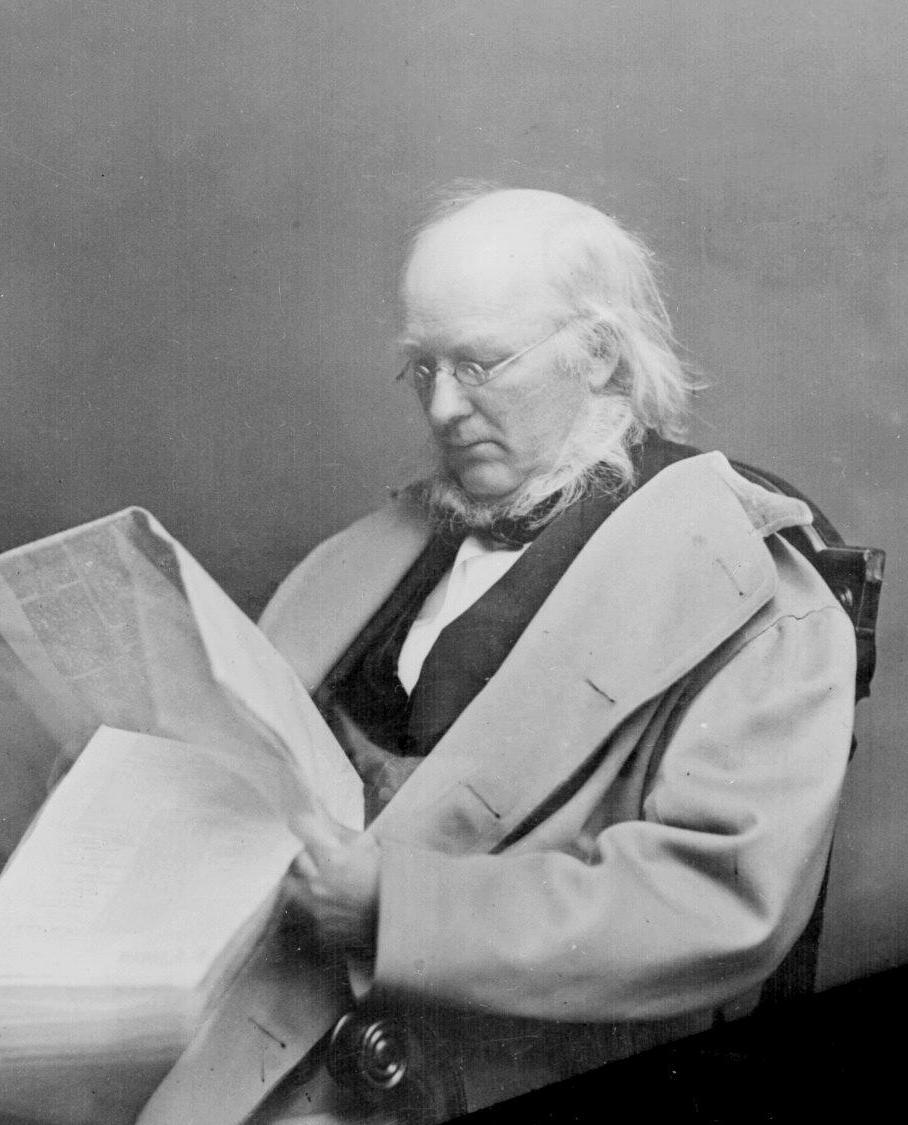

Abolitionist voices. However, the Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society and publisher of the newspaper, The Liberator, wanted abolition to occur immediately and fully. He even went so far as to accuse the U.S. Constitution of being a pact with slavery. This ranked him among the most radical of the Abolitionists. A number of other newspapermen, such as Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Tribune, were also constant in their verbal assault on the vile practice of slavery. But this could be a very dangerous issue for newspapermen to pursue. In 1837 an angry pro-slavery mob attacked the newspaper office of the Alton (Illinois) Observer run by the Abolitionist and Presbyterian preacher Elijah Parish Lovejoy, the fourth such attack on him and his press. But this time they murdered him, making him a martyr to the Abolitionist cause and pushing his brother Owen into the leadership of the Illinois Abolitionists. 1Jefferson,

for instance, though admitting the wrong of slavery, could not bring

himself to free his slaves. Instead, in his will, he required the sale of

his slaves to other slaveholders to pay for the debts he had run up by

constantly redesigning his Monticello home in his effort to perfect it

as a miniature utopia.

|

|

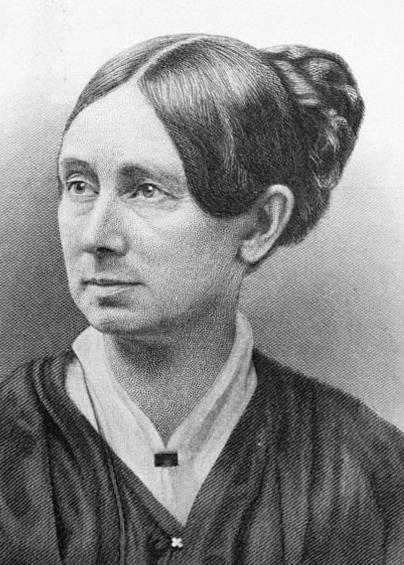

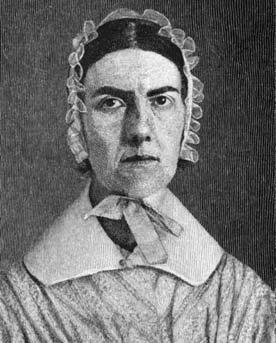

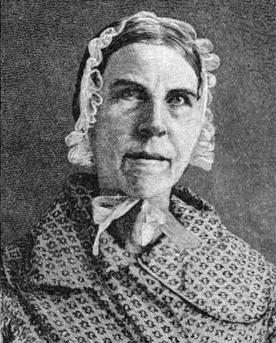

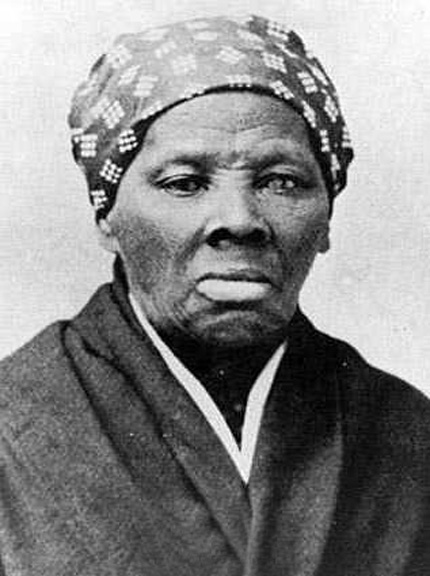

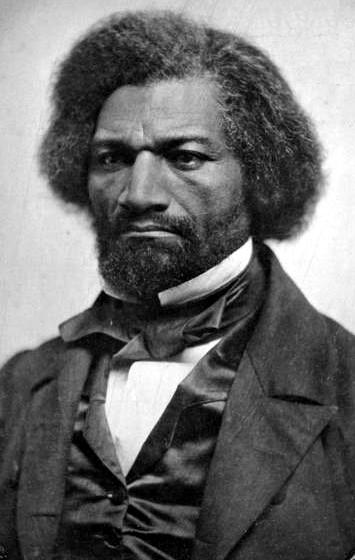

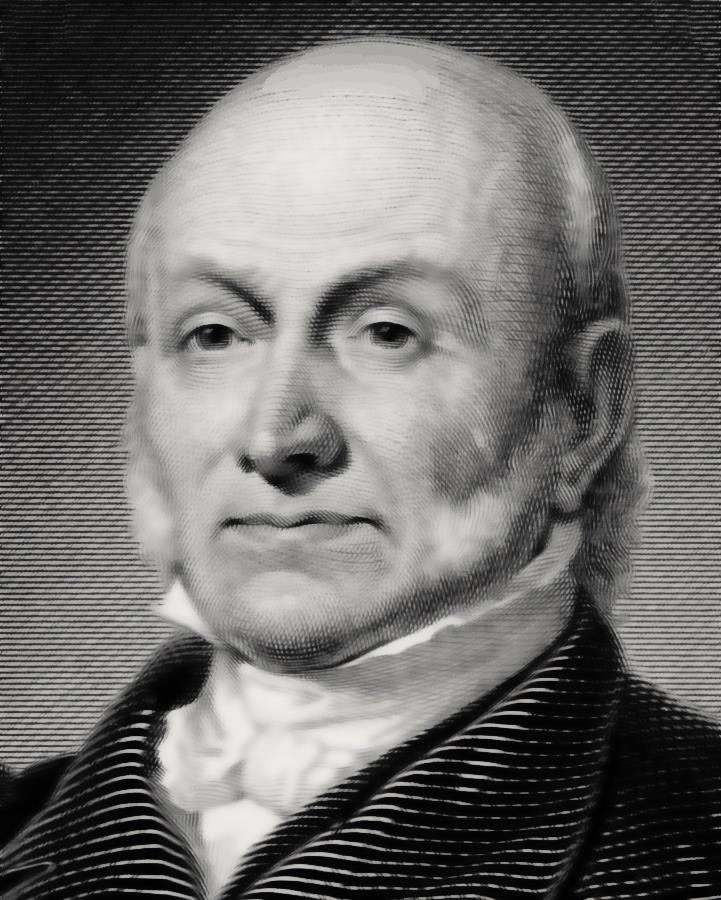

The Abolitionist cause was also moving front and center in the midst of a growing feminist movement in America. Alongside the temperance movement to slow down or prohibit entirely the consumption of alcohol (Amelia Bloomer and Harriet Beecher Stowe), the public-school movement to extend public schooling into the poorer neighborhoods of America's fast-growing cities, and the movement to reform prisons and insane asylums (Dorthea Dix), the call for the abolition of slavery stirred women to tremendous public action (making even some male social reformers nervous!). The Grimké sisters, Angelina and Sarah, were Southerners who moved to the North to get away from the horror of slavery. And from their new home in the North they dedicated themselves to opposing the practice by any means possible, particularly through the distribution of pamphlets and lecturing around the country. As a Quaker, Lucretia Mott put her views to work in lectures enjoining women to see it their duty to push for the immediate end to slavery. Also joining the Abolitionist movement would be future suffragists (demanding the right of all women to vote) Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone. Free Blacks also joined the Abolitionist chorus, speaking from the horror of personal experience. Thus Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman worked actively in support of immediate freedom for the slaves, Tubman becoming active in aiding escaped slaves to head North through the Underground Railroad and Sojourner Truth joining the speaking circuit to publicize the need for immediate action on the issue. But undoubtedly the most important voice coming from the Black community itself was that of Frederick Douglass, whose obvious intelligence put to lie the idea of inherent Black inferiority on which the South built its moral case. Douglass was one of the greatest orators and writers on the subject, his books Narrative of The Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) and My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) both becoming best-selling works. And working from within the political system was once the ever-vigilant John Quincy Adams. He had taken the bold course of presenting himself for election to the House of Representatives in 1830, after having lost to Andrew Jackson his bid for reelection as president in 1828. Then as a Massachusetts representative in the House, he proved to be far more politically effective than he had been as president. And on the basis of his strong opposition to slavery he built an ever-growing reputation, both in focused support and in focused opposition. He had simply ignored the 1836 gag rule and pushed the issue ever before Congress, frequently by stirring his pro-slavery opponents to wrath and thus actionable rebuttal. He had made dedicated enemies, of course. But he also had begun to have his impact in Congress, as he rose higher as a clear moral voice that constantly forced Congress to face the issue of this vile institution. He even became close friends with his former arch-rival within his Whig Party, Henry Clay.

|

Female

voices against slavery

|

The slave-holders' moral response

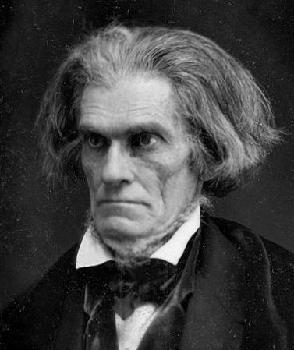

Southerners, such as the fiery-tongued Calhoun of South Carolina, were quick to react to the moral condescension coming from the Abolitionists and soon formulated a moral reply of their own. As the slave-holders themselves now in essence put things: slavery existed as a divine ordinance of God himself because Blacks were unable to function outside the system of mastery by the Whites. Thus slavery was more than merely a legal matter. It was a racial and even religious matter as well. Whites and Blacks were two different breeds of people, obviously (to any reasonable observer) unequal in their nature or character. Blacks were clearly destined by God himself to serve (as the sons of Ham) the superior White race.2 Messing with God's ordinance, as certainly the Abolitionists were doing, was itself going to bring on America the wrath of God. The moral chasm deepens.

So there it was. Two opposing viewpoints, both

enshrined with a keen sense of divine legitimacy, both employing

precise human logic to develop and deepen their two contradicting moral

positions. There was no way that the issue therefore was going to

simply go away on its own. The challenge of answering the moral

question of slavery had spun America into two moral camps with only a

small and rapidly declining moral realm still uniting them. Once again, Human Reason was not going to provide America with any clarity or Truth that could bring it out of this growing hostility. Human Reason merely fortified the two bitterly opposing social viewpoints, even at this point religious worldviews. Conflict – vicious conflict – was increasingly the only way this critical issue was going to be resolved. 2Because Ham saw the nakedness of his father Noah, this Biblical pronouncement fell upon him and his descendants: "Cursed be Canaan [son of Ham]; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, blessed be the LORD God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant" (Genesis, 9:25-26 KJV). "Hamite" was a term applied to one of many African groups, and Southerners concluded that it was through this Biblical reference to Ham and his descendants that the curse of servanthood fell eternally upon the Hamites, i.e., those of African descent. Clever, but horribly flawed, logic – not to mention terrible Biblical exegesis [analysis]! But it seemed to many Southerners to suffice as a compelling moral argument.

|

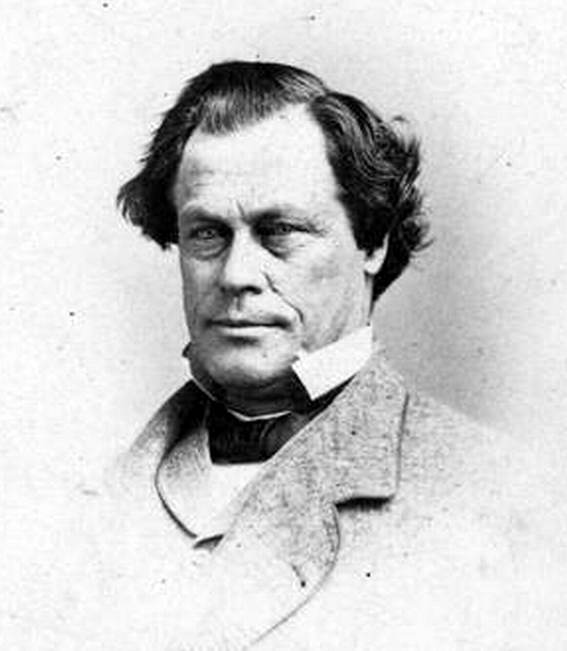

| After

serving as U.S. President, Adams returned to Washington in 1830 to

serve in the House of Representatives, where he became a very active

supporter of Abolitionism. On the other side of the issue, Calhoun became the voice of the angry South, claiming even Biblical support for slavery ... and supporting strongly the departure of the South from the Union if slavery were in any way restricted or outlawed. |

|

|

Zachary Taylor elected U.S. president (1848)

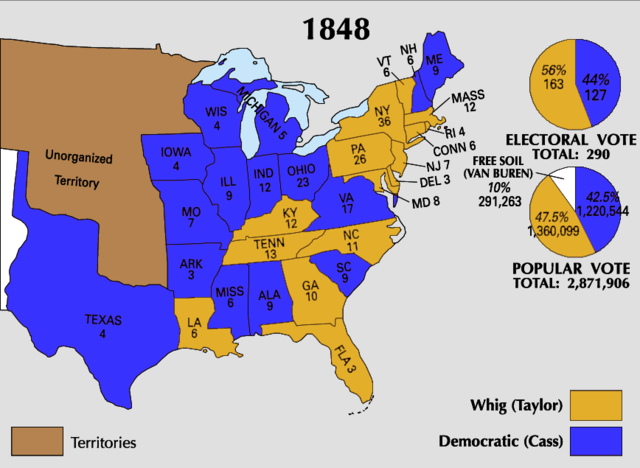

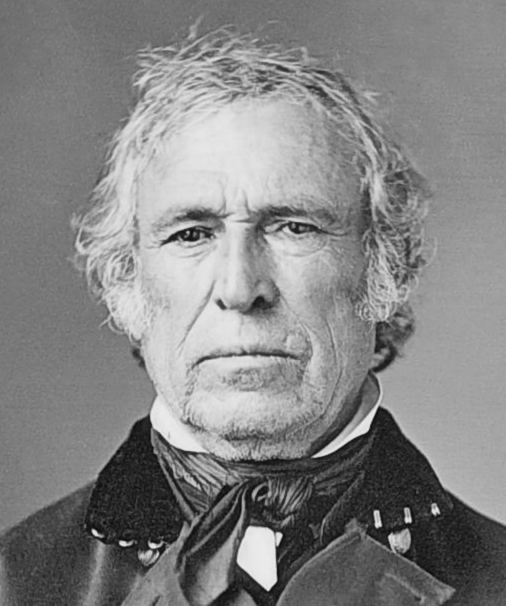

Clay now supposed that he had the Whig nomination all sewed up as he approached the nominating convention in Philadelphia. But the Mexican-American war had put General Taylor front and center in the hearts of the American people, especially among a younger generation that had less reverence for the Great Compromiser Clay. Similarly, the long-standing political star Daniel Webster suffered from the same loss of relevance to the younger generation. Webster finally threw his support behind Taylor, who in turn offered him the position as his vice presidential running mate, which Webster declined (though when Taylor died sixteen months into his presidency, Webster would regret not having taken up the offer). So Taylor turned to the strongly anti-slavery New Yorker Millard Fillmore as his running mate. Taylor's political views were largely unknown. He was a Kentuckian and a slaveholder (a rather unusual social profile for one who confessed himself to be a Whig), though he seemed to have no strongly-held views on the issue of slavery. He was a soldier first and foremost, a strong American nationalist, and a national hero. And that is what the American people found so appealing about him. Running against the Whigs was a new face in the competition, a new third party, the strongly Abolitionist Free Soil Party, which ran Van Buren as its presidential candidate (actually drawing about ten percent of the national vote). And, as usual, opposing the Whigs – but also now the Free-Soilers as well – was the pro-states'-rights Democratic Party, with its strong Southern support, which ran Lewis Cass as its presidential candidate. In the election itself, in which the voter turnout was quite light, Taylor won a slight (five percent) majority of the popular vote, although he ultimately received 163 electoral votes to Cass's 137 votes in securing for himself the U.S. presidency. All in all, the election was a clear indication that the nation was ready for a break from the tensions of the Mexican-American war and the slavery issue. But sadly, the latter was not destined to be.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges