|

|

The American-Indian Wars during the Civil War The American-Indian Wars during the Civil War  The routes West The routes West

Cowboys and farmers Cowboys and farmers

The Indians' "Last

Stand" The Indians' "Last

Stand" The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 329-339. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

Wars between the American settlers and the American Indians had been going on, of course, virtually since the arrival of Englishmen to the shores of North America in the early 1600s. Certainly they continued even while America was caught up deeply in its Civil War – and particularly during those times – because federal troops protecting settlers had been pulled from Western service to fight the Confederacy. Thus the Civil War days saw some intense fighting between the settlers and the Indians. There were hundreds of Indian attacks in an Indian effort to drive the White settlers off their lands. There was no sparing of women, children and the elderly as these were battles of whole communities over the matter of land ownership, vital to the survival of both Indians and Whites. In the span of the four years of the Civil War over a thousand settlers' lives were lost to these Indian attacks The Sioux War in Minnesota The most intense action occurred in Minnesota in 1862 when Dakota tribes attacked German settlements at New Ulm and Hutchinson, killing several hundred (300-400) settlers. Local militiamen did what they could to hold back the Sioux, and Lincoln quickly sent federal troops to help them. Battles thus broke out between the federal and Indian troops over a six-week period, resulting finally in breaking the Sioux offensive. Over 400 Sioux were subsequently arrested, 300 of which were convicted of murder and sentenced to be hanged. Lincoln however pardoned most of them (much to the great irritation of local White authorities) and only thirty-eight of them were subsequently hanged, the largest such event nonetheless in American history. The Sand Creek Massacre Ultimately such Indian attacks brought a bitter White response, in the form of countering attacks of White militia and federal troops on the Indians. There was an attempt to be fair in the size of the response. But the anger raging between both sides made this a matter very difficult to manage. A huge and unwarranted loss of Indian life during this period occurred at Sand Creek in eastern Colorado in late November of 1864, when some 700 federal troops attacked a peaceful community of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, most of whose men were away hunting buffalo. 130 were killed or wounded, mostly women and children but also a number of the members of the Cheyenne Council, tragically those most supportive of the idea of peace with White society. This action thus strengthened the hand of the pro-war Indian Dog Soldiers. It also brought into action a federal court of inquiry and condemnation of the federal officers involved. But no other punishment resulted.  Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanches Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and ComanchesMeanwhile in the American southwest, action led by Union General Carleton – but carried out largely by the living legend Kit Carson1 – was undertaken in early 1863 to round up the Navajo and Apache tribes and move them to a reservation along the bleak Pecos River, where they could be more easily prevented from making raids on the White settlers in the New Mexico Territory. The roundup proved difficult because the Indians knew how to hide themselves in the mountains, driving Carson to take harsher measures to break the will of the Navajo (the ones who had not already joined the Apache in a flight to the West to form an anti-White army.) By early 1864 Navajo resistance had been broken and thousands of them were rounded up and sent off to the reservation, where many died of cold and hunger. Eventually they were allowed to return to their former homes, though as a submissive people. By late 1864 Carson had turned his attention to the Kiowas and Comanches who had been conducting raids on White settlements in the Texas Panhandle region. In November Carson and his men met a grand Indian coalition of several thousand warriors at the Battle of Adobe Walls. Carson's men were vastly outnumbered and quickly out of ammunition and thus forced to retreat, but managed to inflict massive casualties on the Indians in the process. This battle proved to be a turning point in the Indian wars in the region, greatly undermining the power of both tribes and ultimately bringing the Kiowas and Comanches to sue for peace in 1865. 1Penny novels were already being written about his exploits as a mountain man and Indian hunter.

|

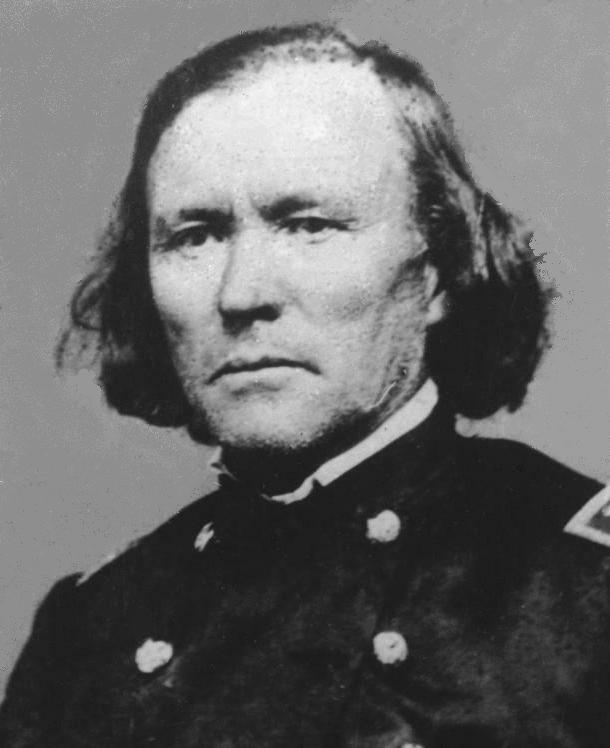

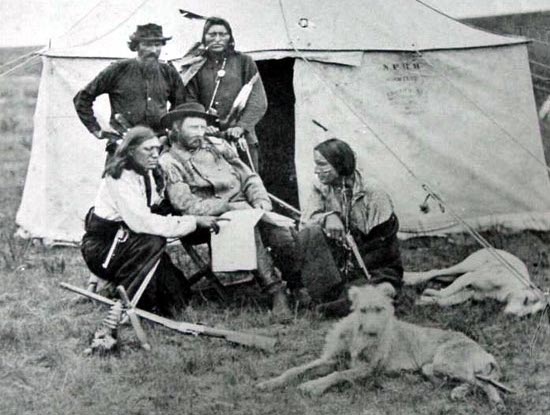

Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer with his favorite Indian scout, Bloody Knife (kneeling left)

Gen.

William T. Sherman and commissioners in council with Indian chiefs

at Ft. Laramie,

Wyoming – ca. 1867-1868

The National Archives

|

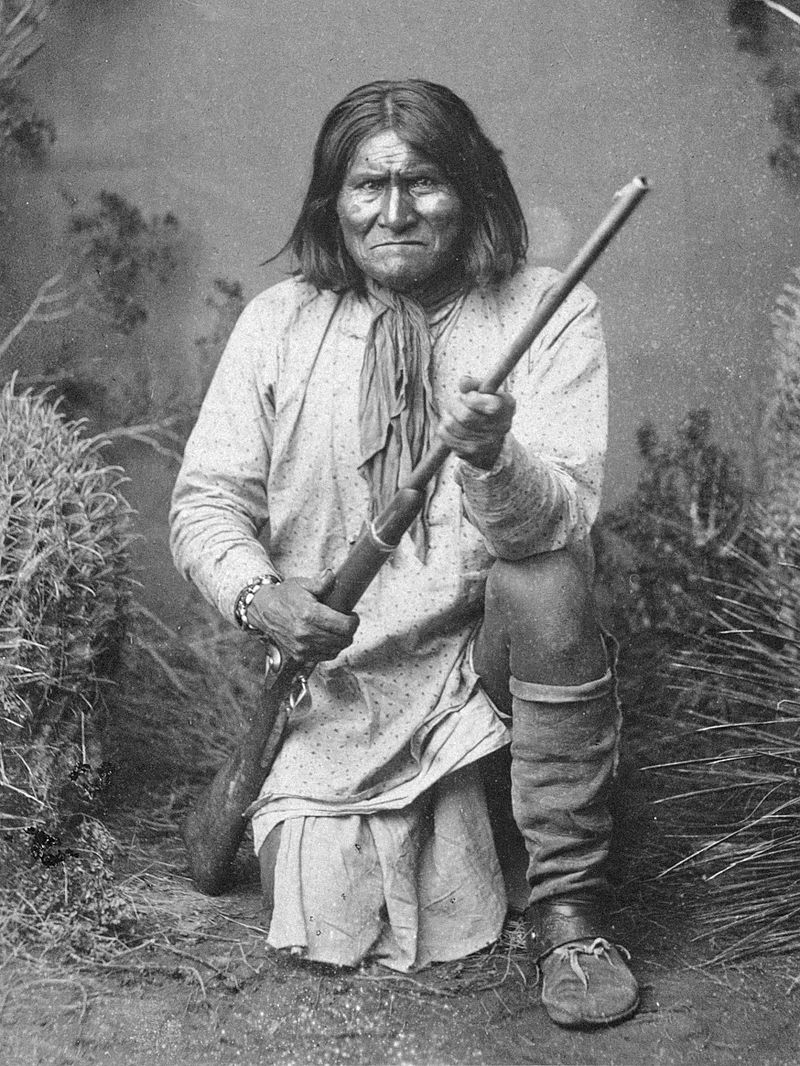

Geronimo and his Apache raiders

But alongside Kit Carson, the Indians could provide heroics of their own, such as the Apache raider Geronimo. He was part of a military tradition that reached back to the wars earlier in the 1800s between the Apaches and the Mexicans. These wars were constant and without definitive results. Then when the American frontiersmen came on the scene, Geronimo included their settlements in his raids. He actually never commanded a band larger than forty or fifty warriors. Yet his skills brought his name to some kind of fame among the Apache – and the White settlers as well! He eventually was forced into retirement on the Apache reservation by the U.S. military (with also Mexican cooperation), breaking out three times between 1876 and 1886 when he grew restless under the restrictions of reservation life. Eventually he and his Chiricahua tribe were moved to Florida and then to Oklahoma. But his name was so well known that several times he was featured at several major expositions back East and even rode horseback (in native attire, of course) in Teddy Roosevelt's inaugural parade in 1905!

|

A band of Apache Indian prisoners at a rest stop beside a South Pacific

train – Sep 10, 1886

Among

those on their way to exile in Florida are Natchez (center front)

and,

to the right, Geronimo and his son in matching shirts.

The National Archives

|

|

The grand Western migration

On they came – White men, women and children – by steamer or river barge (as far as the rivers would take them westward), then by wagon train, following trails set out by trail-blazing frontiersmen, and eventually by train as the American railroads pushed West and Southwest deep into Indian lands. They laid claim to railroad land and set up their own farms, as well as towns to service the fast-growing farming world of the West. The Mormons Some such as the Mormons came looking for religious utopias, much in the manner that had brought the Puritans to America in the early 1600s. Indeed, Brigham Young's Mormons were particularly successful in this matter, developing communities centered on their City of Zion of Salt Lake City (founded by Young in 1847), but reaching far and wide from Utah into Idaho, Arizona, Nevada, California, Colorado, and even northern Mexico. In 1857 a war began to brew between the Mormons and the U.S. government, the latter in 1850, after having secured the area from Mexico in the Mexican-American War, declaring the region to be off limits to the practice of polygamy (a common practice among the Mormons). U.S. troops were sent to Utah to enforce the ruling against the rebellious Mormons, although the Mormons fought back mostly by simply refusing to supply the troops with needed food and material. Then in the summer of 1858, just as the Mormons were making a move to leave Utah, pressure from Congress brought U.S. President Buchanan to declare an end to the Mormon suppression. The war was now officially over and the Mormons returned to their homes in Utah. One unfortunate result of the war however was the massacre2 by Mormons (disguised as Indians) in 1857 at Mountain Meadows in southern Utah of a party of 120 to 140 adult Arkansas "Gentiles" (non-Mormon Whites) passing through Mormon territory with a huge herd of cattle on their way West to California. All were killed, except children under six who were spared however and taken in by Mormon families. Blame for the massacre was never fully ascertained (Young claimed to have had no involvement in the decision to execute the group of Gentiles), and only in 1877 was one of the supposed perpetrators finally successfully tried and executed. Miners

The rumors of gold (but also silver and copper) also brought Americans west, though not usually entire families but instead merely single male fortune hunters. States such as California, Nevada (with its fabulous Comstock Lode), Montana, Idaho, and Washington were states particularly sought out by these fortune hunters. Towns would quickly appear wherever mineral sites were discovered, bringing not only the fortune-hunting miners, but also barkeeps and prostitutes to entertain the miners, but also bankers, clergy, and general store operators to bring some degree of American civilization to the towns as well. Then when the mines yielded up all their bounty, everyone moved on to opportunities elsewhere – and then yet another bustling mining town would turn into a deserted ghost town. 2The

decision to massacre the entire group was made when the Mormons feared

that some of the Gentiles had discovered that their attackers were

Whites (Mormons) and not really Indians.

|

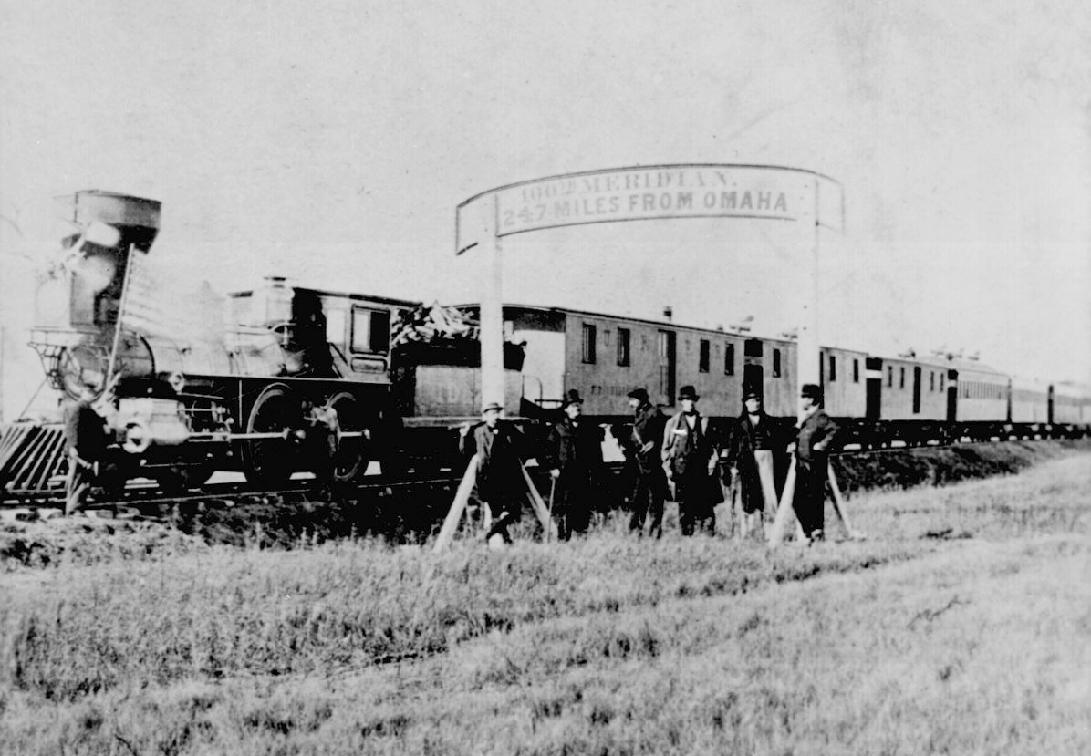

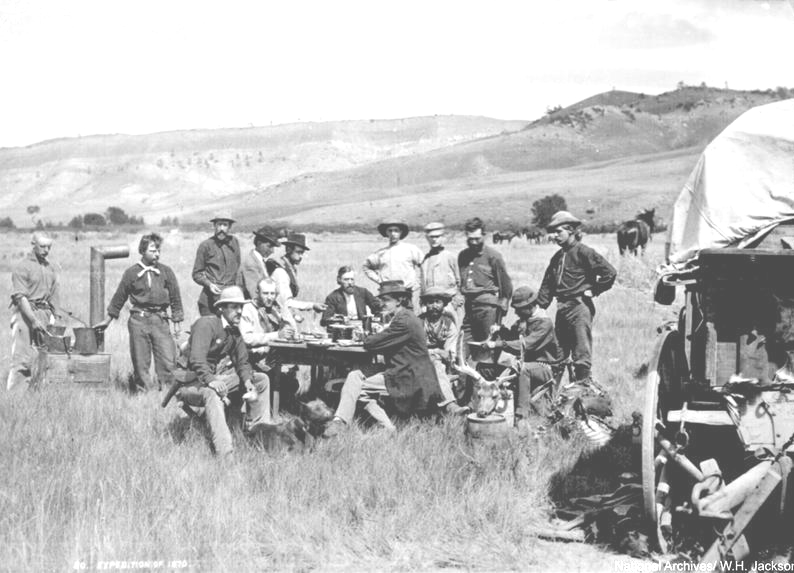

The train in the

background awaits the party of Eastern capitalists, newspapermen

and other

prominent figures invited by the railroad executives

The National

Archives

Campsite and

train

of the Central Pacific Railroad at the foot of mountains

The National Archives

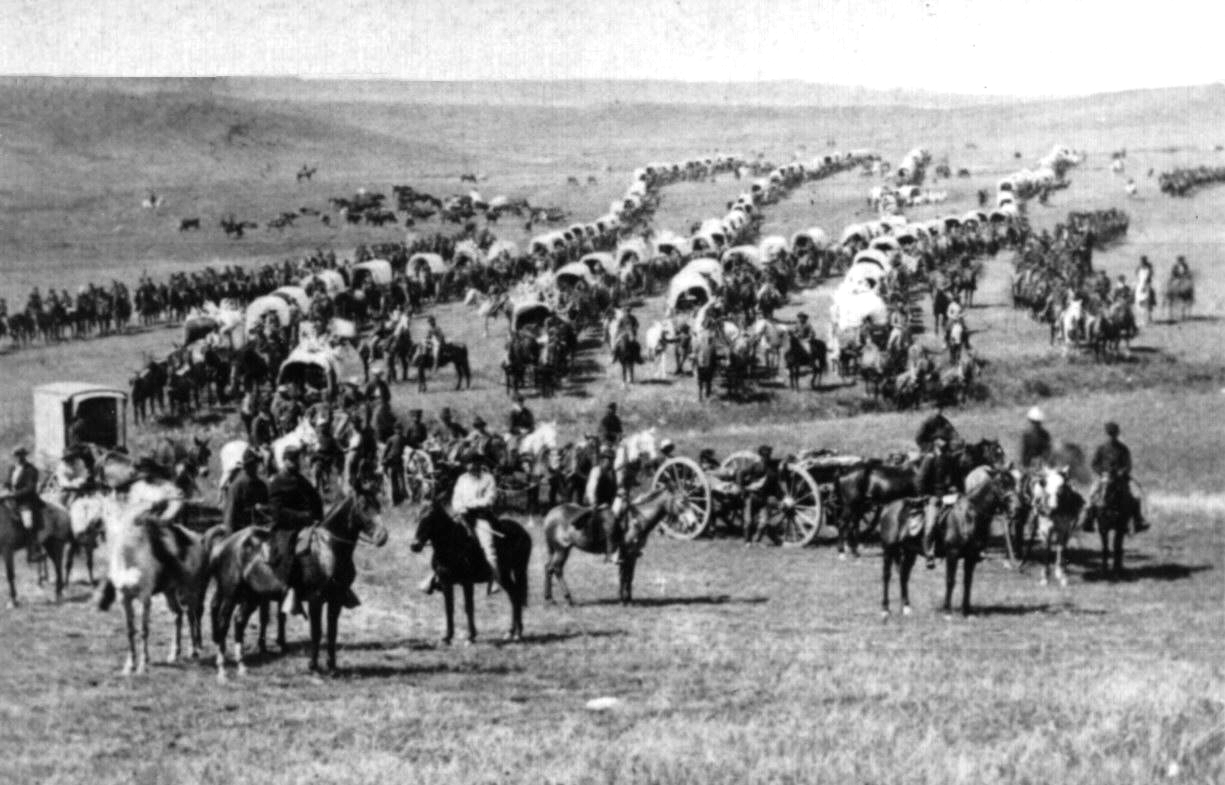

crossing the plains of Dakota

Territory – 1874 Black Hills expedition

The National Archives

The National Archives

|

|

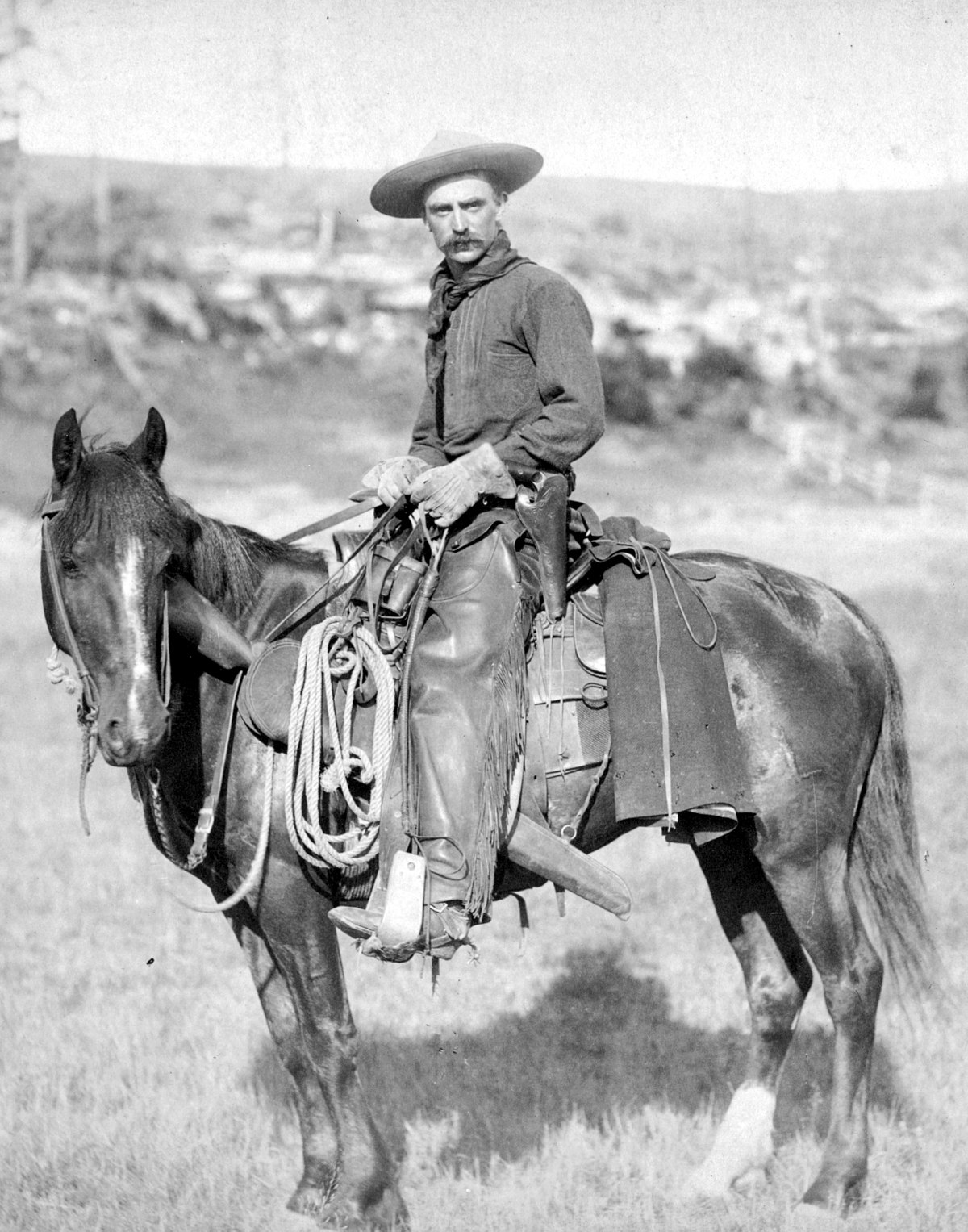

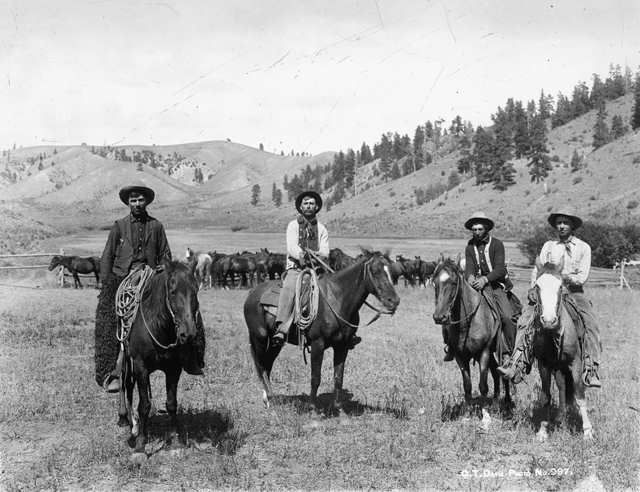

The West's Cattle Kingdoms (1860s–1880s)

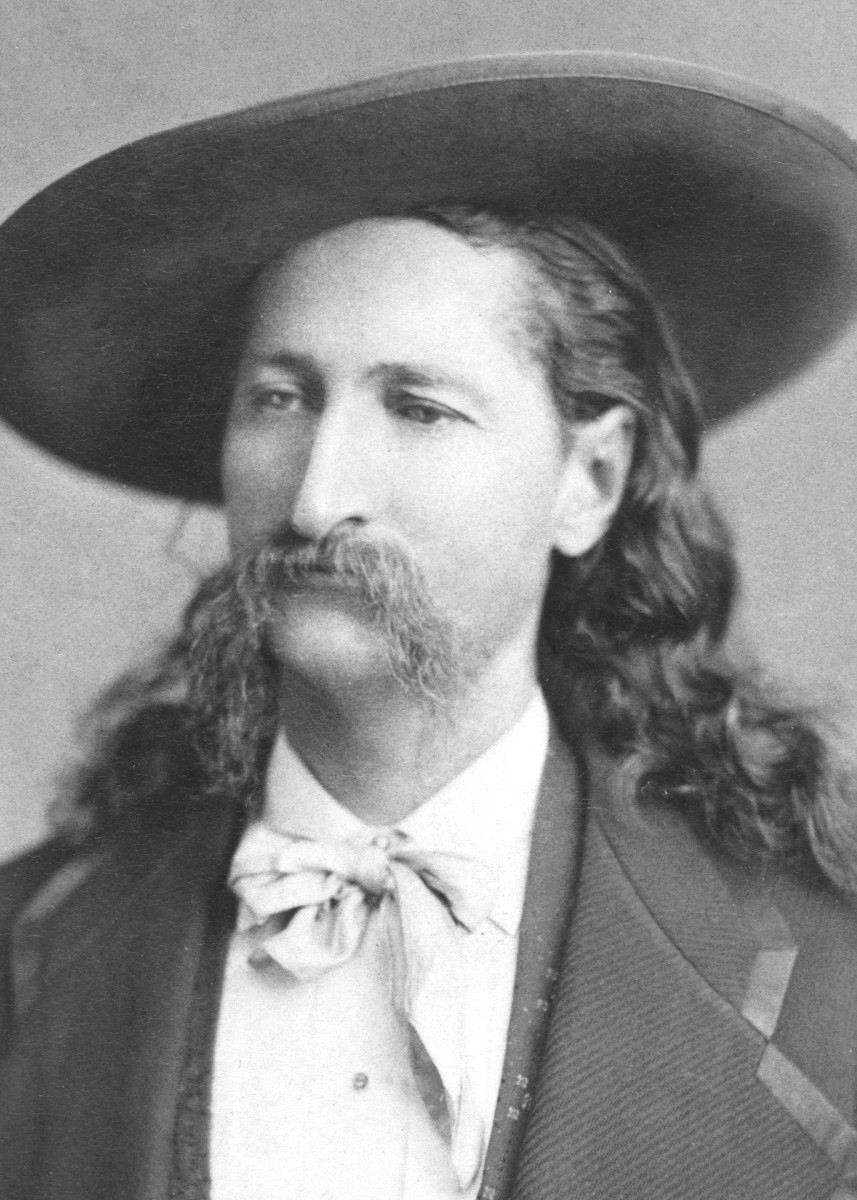

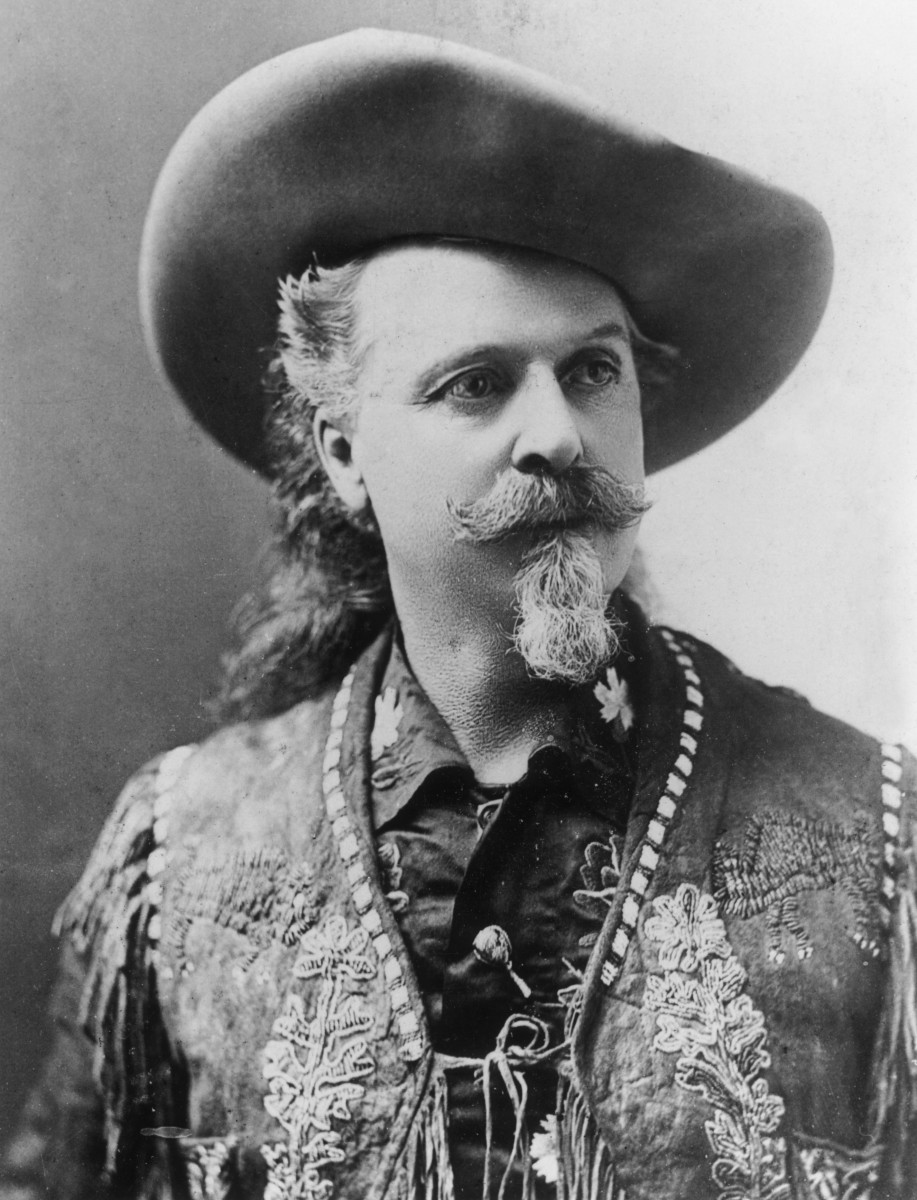

Cow trails and cattle barons. With the advent of the railroads into the West, new opportunities opened up for the lucrative trade in beef cattle. Thousands of cattle would be herded north from the grasslands of Texas, through the Indian territory of Oklahoma, to the various railheads of the Kansas Pacific Railroad. For instance, in 1867, when the new Chisholm Trail was first laid out, 35,000 head of cattle were brought up from Texas to the railhead at Abilene in that first year alone. From Kansas the cattle were then herded onto boxcars and shipped up to Chicago (or west to Denver for shipment to the Pacific coast). In Chicago the slaughterhouses would be kept busy preparing meat to be shipped up the Great Lakes waterway to the populous Eastern cities. The fabled cowboy. From the end of the Civil War to the mid–1880s the cattle business boomed, making a lot of cattle barons very rich – and creating a fabled American proto-type, the American cowboy. The battalions of cowboys conducting these drives were hard-working, hard drinking, young men on whom endless popular stories of American fortitude would be based. They were a restless lot, not destined to set down family roots while they remained in the business of cattle herding. Greatly exaggerated however were the multitude of stories of gun battles conducted by them in the Kansas bars, where, being finally paid for their work, they were supposedly emboldened by booze and prostitutes to the point of murderous manliness (but still, these stories made for great reading!). Nonetheless, the cowboy exemplified a spirit that seemed to simply roll out of the manliness demanded of the American male during the Civil War. The cowboy was, indeed, an inspiring symbol of a young, aggressive, expansive America, a nation with a growing sense of destiny.

|

|

Cattleman versus farmer

But three things would bring this era to a close: the steel-bladed plow, the barbed-wire fence, and the overgrazing of the cow trails. The grassy plains through which the cattle trails led were covered by a thick undergrowth of tough grass with deep roots, which made the land prohibitively difficult to plow – that was until the steel plow began to come under wide usage (sometime in the 1870s and 1880s). With this invention, homesteaders could now begin to settle the plains, with their plowed fields and domestic animals able to support the lives of their families. To protect their investment, they began to secure their landholdings by the relatively cheap means of the new barbed wire fencing (developed in the mid–1870s). Now the cattle herds found their paths along their cow trails blocked here and there by these fenced-in homesteads, and trouble began to brew between these two categories of Westerners, the farmer and the cattleman. For years the cattlemen had been allowed freely to graze their herds on the vast federal lands of the Great Plains (reaching from Texas to the Dakotas). But now homesteaders were rapidly filling these open lands. Little by little the cattle herding business was pushed ever more westward, increasing the difficulty and costs of the herding itself. Furthermore, the herds had expanded to such a size that the price of beef began to drop – at a time in which the cattle lands and trails were beginning to be overgrazed by this vast number of cattle. When a very bad winter hit in 1886–1887, hundreds of thousands of cattle died from exposure and the lack of sufficient grass or even grain for feed. A number of cattle barons never truly recovered from this bitter blow.

|

|

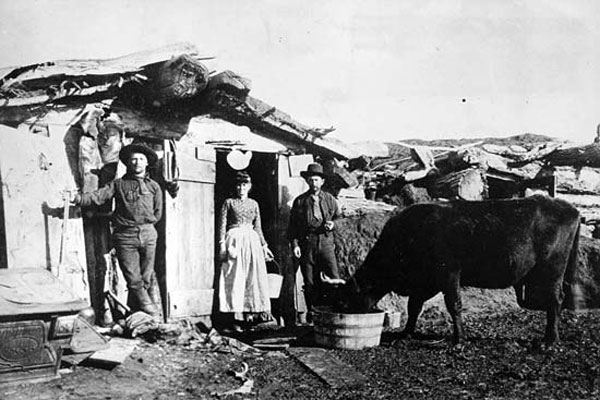

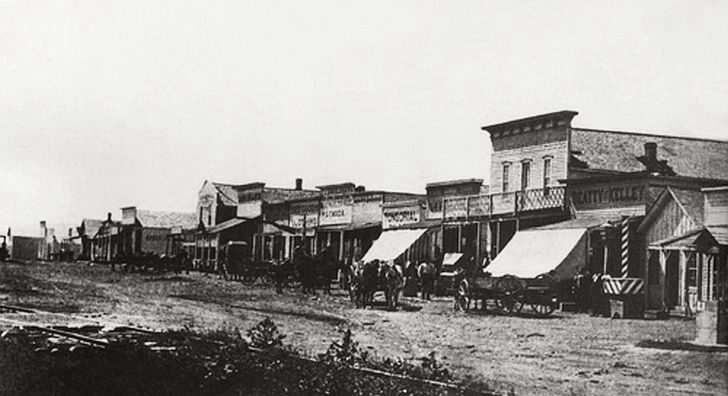

The Rapid growth of the American West

The rise of the American farmer. Anyway, the business of farming was slowly taking over from the business of cattle herding. And truly a business it was. The families who came West and acquired their 160-acre tract of land found that 160 acres in the West did not provide the financial security that 160-acres in the East once had. At best these small homesteads could feed their large families. But beyond that, there was little additional income from their fields that could allow them to purchase the extras needed for the good life. For instance, the Great Plains was devoid of woodlands and thus wood had to be purchased rather than simply cut from the surrounding woods as was the case back East. Sadly for many homesteaders, their sole building material was the sod they cut from the ground and turned into something like bricks to frame their houses and barns. The sod houses that dotted the landscape of the Great Plains were hardly a lasting solution to the challenge of settling the West. In short order, numerous homesteaders (perhaps as many as three-quarters of them) had to simply abandon the effort and move on to try their luck elsewhere. But this opened the opportunity for the more entrepreneurial-minded homesteader to pick up abandoned neighboring land, adding to his holdings until he possessed many hundreds of – even a thousand – acres of farmland. This was nicely timed with the invention of farming machinery that made the plowing, cultivation and harvesting of vast fields an attainable goal for an industrial farmer. And indeed, America began to see such industrial farms grow in number during the latter part of the 1800s. In America, farming had finally become very big business, the Western farms fully able to feed the Eastern cities which were also growing rapidly in size. Urbanization comes to the West. Towns located along the growing number of rail lines crisscrossing the American Great Plains or Midwest began quickly to develop as economic and social centers for the agricultural industry of entire counties. Thus as the farming business boomed, churches, schools, banks, and general stores began to appear in these towns, bringing American civilization to the Midwest. In many ways this too, along with the cowboy, was fast becoming a major cultural symbol representing the young and fast-growing America. Meanwhile... the American South. Sadly the South had slipped out of the picture, caught up locally in trying to heal the economic and cultural wounds left by the Civil War. It would take many generations before the South was finally able indeed to rise again.

|

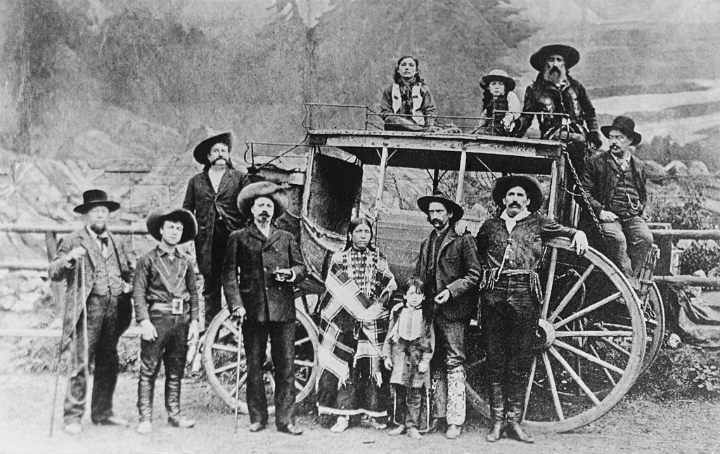

And lawmen to keep some semblance of order in the midst of the rowdy crowd

And there were the celebrities to add a sense of adventure

to those watching frontier life from afar

|

|

At the end of the Civil War whatever Indian communities still remained East of the Mississippi were quite small and isolated, hardly registering at all in the social-political scheme of things. However, in the American Southwest, widely scattered communities of Navajo and Hopi maintained something of an undisturbed, though marginal, agricultural existence (their land was arid, even much of it desert.) Neighboring Apache meanwhile led a nomadic lifestyle hunting game from horseback. In the American Northwest a number of tribes led fairly comfortable and quiet agricultural lives, along the lines that the Eastern Indians had once led, prior to the arrival of the Europeans. The most active, and violent, Indian-European dynamic was on the Great Plains, where Indians constantly struggled against White Americans for control of the land. The Plains Indians had once been farmers. But with the rapid growth of the herds of Spanish horses that had escaped to the wild – horses that the Indians learned how to tame – the Indians had developed great skill as horsemen and left the farming world for the world of the hunter, becoming dedicated hunters of the vast bison herds which covered the Great Plains. They had so completely adapted to the lifestyle of bison-hunter that without these herds to hunt they would not know how to survive. And therein lay one of the biggest problems for them. The other problem of course was like the one also faced by the American cowboy: the American homesteaders who were moving onto the Great Plains to establish fenced-in farmlands for themselves and their families. By the last quarter of the 1800s it was increasingly apparent to the Plains Indians that the two societies could not coexist. For the Indians, survival meant simply chasing the American homesteader off the land. Thus Indian-American war loomed. The decline of the buffalo herds

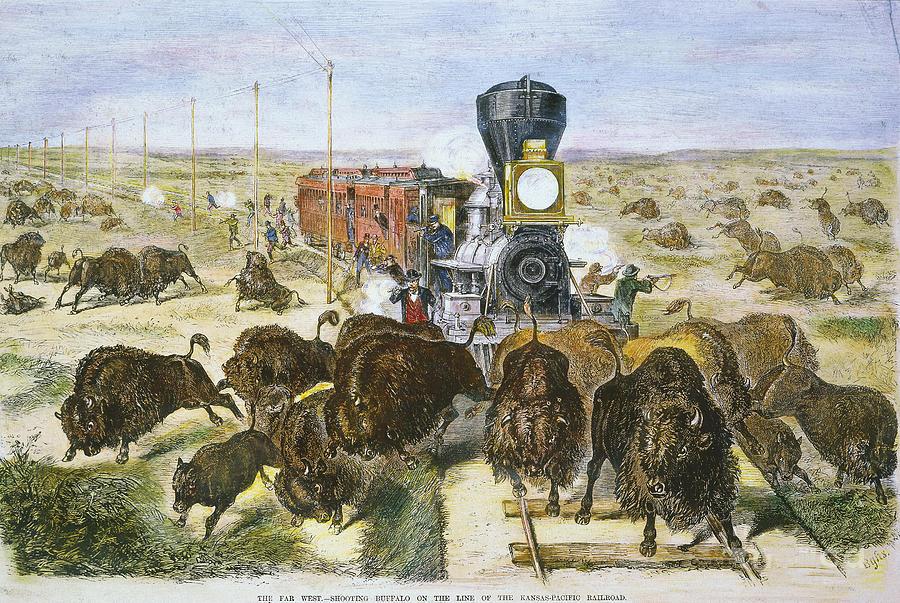

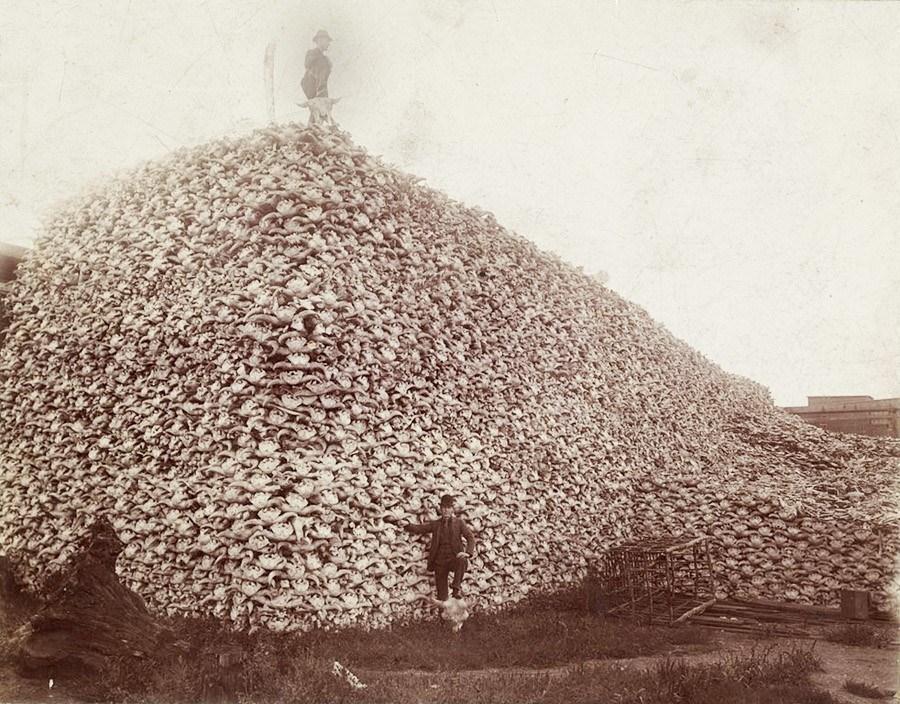

Concerning the bison or buffalo herds and their rapid decline, there is still much controversy as to the cause. But certainly the effect was clear enough: deprived of their buffalo, the Plains Indians could not survive as a society. Explorers to the West prior to the Civil War were astounded by the size of the buffalo herds, hundreds of thousands of them in a single herd. But already by the time of the Civil War the herds were beginning to thin out. The Plains Indians themselves were well-known for their extravagance in the killing of the herds, given their own marksmanship with the hunting rifle and skill on horseback. The herds also lacked protective instincts and so they were easily slaughtered in vast numbers. The Whites of course also participated in the slaughter, hunting them for their hides, sometimes just hunting them (for instance from passing trains) for sport – or ultimately to deprive the Plains Indians of their sustenance. By the 1880s the total number of buffalo had dropped to only mere hundreds, to the point of near specie-extinction.

|

|

The debate over what to do about "the Indian Problem"

While events on the frontier itself seemed to take their own course as frontiersmen saw the necessity, back East a huge debate raged over what the proper policy toward the Indian should be. Humanism was a response natural to those back

East who were comfortably removed from the terror of frontier life. In

a Rousseauian fashion,3 Humanists took the rather romantic view of the

Indian as the pre-civilized natural man, possessing all the pure or

sinless qualities of man that he possessed before Adam and Eve's Fall

into sin (or before the corruptions of civilization had produced their

disastrous effect). Humanists thus believed that the Indians should be

simply left alone, that White intrusion into the West should be slowed

up or even halted completely. But that romantic dream was also simply

not going to happen. Thus the Humanist program was largely irrelevant

to the solution of the Indian Problem. Others, notably evangelical Christians, felt strongly that God wanted Christian Americans to help the Indians come out of their primitive (and pagan) ways, to personally bring them the good news of the higher life to which God called all his American children (including the American Indians). Thus missionaries took themselves to the tribal lands of the Indians to bring them to Christian ways and to the life-style of Anglo-Americans – setting up schools and churches to show the Indians the way to proper or civilized life. But as the Cherokee and other Southeastern Indians themselves had discovered earlier in the 1800s, converting to the settled, agricultural, Christian life-style of the White frontiersman did not guarantee any kind of larger protection when these White frontiersmen sought their land. Thus ultimately this was not a terribly good solution to the Indian Problem, at least not from the Indian point of view. Ultimately the decision came in the form of the policy of rounding up the nomadic Plains Indians tribes and placing them all on Indian reservations, promising that within those reservations they could live as they chose – but that they were not ever to leave those reservations or they would face the wrath of the U.S. military sent to enforce the reservation policy of Washington's Bureau of Indian Affairs. As Commander of the U.S. military enforcing that policy, Civil War veteran cavalry leader General Philip Sheridan proved to be a strict enforcer. The only problem here was that the Indians themselves knew from previous treaties undertaken with the U.S. government that these reservations were generally only temporary promises of respect for Indian rights, before such reserved territory was once again taken away from them by land-hungry Whites. Ultimately, the Indians understood that they were going to have to have their own say in shaping policy, which meant only one thing: they were going to have to fight – and fight savagely – to protect themselves from extinction as a unique society or people. Custer's Last Stand

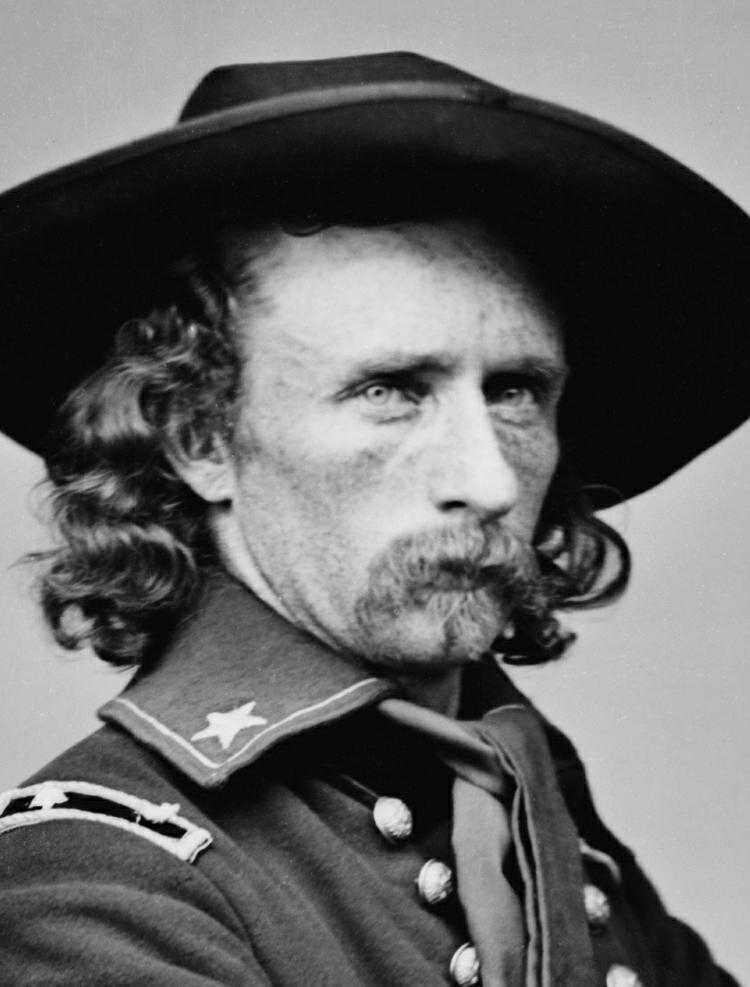

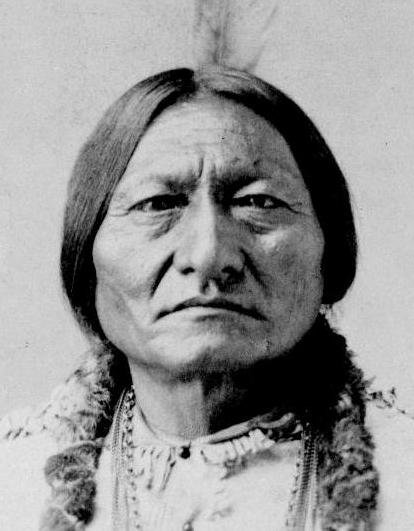

Meanwhile, wars between the Indians on the one hand and White settlers and U.S. Army units on the other had been fairly constant on the American Plains since the days of the Civil War, with the Indians typically receiving the worst end of these encounters. But by the mid–1870s the Indians were putting aside their ancient tribal differences and beginning to work in concert with each other. Thus in 1875, Sioux (or Lakota) Chief Sitting Bull and his tactician Crazy Horse decided it was time to leave the Dakota Reservation to take to the offensive against settlers invading the Dakota Black Hills, sacred Sioux land. By the summer of the next year (1876) Sitting Bull had linked up with a large number of Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors in Southern Montana. Sent to deal with this huge gathering of thousands of Indians was Sheridan's cavalry. Sheridan divided his cavalry into separate units, to converge on the huge Indian gathering from three different directions and force these Indians back onto their reservations. Things did not go well for Sheridan, as the Indians took on one of these detachments and forced them into humiliating retreat. Trying again, Sheridan sent out 700 troops under the colorful Civil War celebrity, George Custer, Custer dividing his force into a number of units, he himself leading a large detachment of those men. On June 25-26 at the Little Bighorn River he and his soldiers were also to discover the fighting prowess of the Indians, when his entire detachment, including Custer himself, was either killed (268 men) or severely wounded (55 men, 6 later dying from their wounds) in an encounter with Crazy Horse and his warriors. But this massacre did not break the will of the U.S. military. Ironically it had the opposite effect, turning Custer into some kind of iconic martyred hero, and merely deepening the determination of the military to crush definitively all Indian power. Realizing that his actions had simply awakened an angry and massive White nation, Sitting Bull reappraised the situation and decided simply to take himself and his people back to their Dakota reservation. And this would be the last of the great Indian efforts to hold off by force the advancing White Americans. 3Jean-Jacques

Rousseau was a French-speaking Swiss philosopher of the mid–1700s who

in his widely-read book, Social Contract, idealized the "natural man" –

even citing the American Indian as a perfect example – claiming that

sin and corruption was not itself natural to man, but came upon the

social scene only with the rise of civilization. Of course he had the

very obvious corruptions of the European royal courts in mind as he

wrote, and from a commoner's point of view such highly "civilized"

courts (as kings and their attendants saw themselves) were indeed very

corrupt, with their perfumed wigs, expensive entertainment, and general

uselessness as overseers of the lives of the multitudes of Europeans

not part of the privileged class. |

|

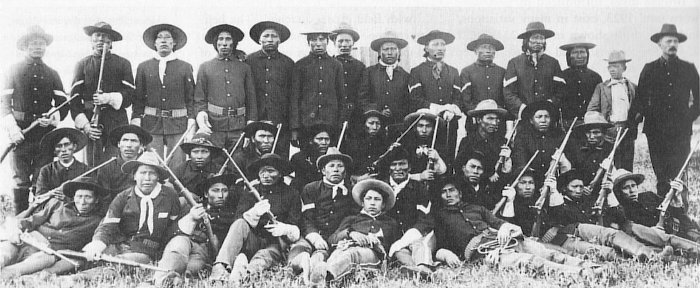

Indians assigned to Reservations under the Dawes Severalty Act (1887). Indians assigned to Reservations under the Dawes Severalty Act (1887). Finally in 1887, Washington came to some kind of conclusion about the Indian Problem when it passed the Dawes Severalty Act. It attempted to turn the Indian reservations into homesteading territories, each Indian family assigned the proverbial 160 acres, all Indians to receive English instruction, and eventually all becoming U.S. citizens. That these proud nomads however were not naturally farmers was clearly demonstrated in the crushing of the Indian social morale, and the widespread alcoholism that quickly descended upon the reservations. But at least from White America's point of view, the Indian Problem had been solved. In keeping with the moral climate of the times, it was not long until the Bureau of Indian Affairs fell right alongside the railroad business into deep corruption. Government money, unaccountable to market forces but distributed solely through political considerations, invited all sorts of patronage appointments, at a cost (kickbacks) of course. But it was not long before a vigilant news media caught wind of the corruption, and scandals erupted into the public view, dirtying the reputations of a number of American politicians. The Ghost Dance, Sitting Bull, and Wounded Knee (1890).

But White Americans were not the only ones to take note of the corruption, which merely added to the Indians' sense of demoralization. Nothing that they could do seemed to improve the Indians' sense of social significance. They were an entirely defeated people. Thus it was that in 1890 the Sioux got caught up in the Ghost Dance craze, believing that the performance of this ritual would finally clear the land of the White man, even with the wearing of special shirts to make the Indians invulnerable to White man's bullets if it should come to armed conflict. And it soon came to such conflict – in which Sitting Bull was killed along with a dozen of his warriors. Then the 7th Cavalry was sent in to impose order and at Wounded Knee even greater fighting broke out, in which 200 Sioux men, women and children were killed – along with 25 U.S. soldiers killed and 39 wounded. It would be the last sad (and probably accidental) such episode in the long-standing feud between the American Indian and the American White. Indeed, the Indian Problem had now been solved definitively.

|

Miles H. Hodges