|

|

|

|

Jane Addams (1860-1935) founder of the Hull House for immigrants in Chicago

Jane Addams

|

|

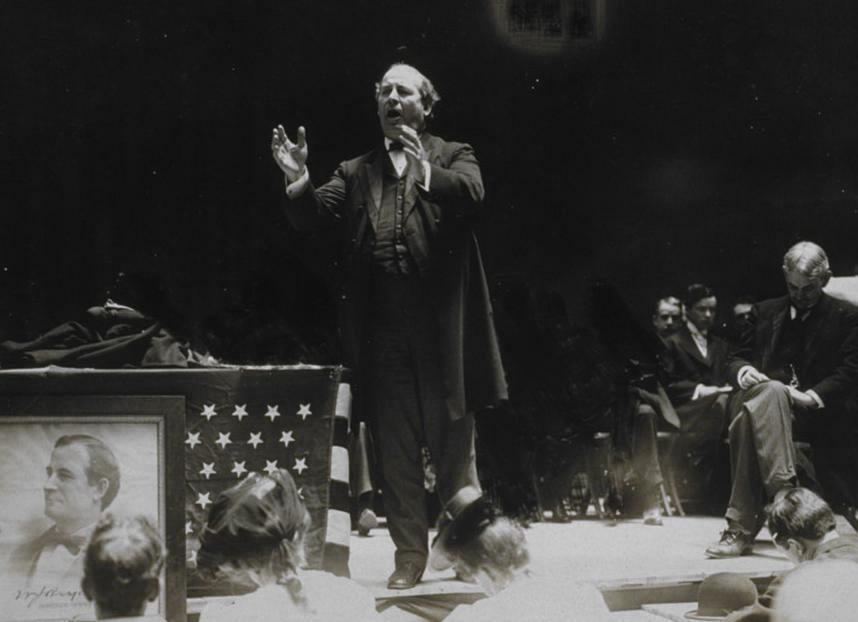

Bryan a hero ... or a major social annoyance?

Bryan was born in rural southern Illinois in 1860 to a Baptist mother and a Methodist father, and went his own way religiously because of a Christian revival when he was fourteen that led him to be baptized as a Presbyterian – the most important day in his life he would say. His father was an avid Jackson Democrat and an Illinois circuit judge and the family lived comfortably and respectably. In order to prepare him for college he was sent in 1874 to attend Whipple Academy in Jacksonville, connected to the Presbyterian Illinois College, which he also attended after completing high school at the Academy. Following graduation in 1881 (he was the class valedictorian) he attended Union Law College in Chicago (the future Northwestern University School of Law). After graduating, he taught high school and married Mary Elizabeth Baird (1884). The two then settled in Jacksonville, where both William and his wife Mary practiced law. Greater opportunity beckoned from fast-growing Lincoln, Nebraska, and the Bryans moved there in 1887, where he soon became involved in local politics. He ran for U.S. Congress in 1890 and was carried into office with the landslide victory of the Democratic Party that year. He was reelected two years later but then in 1894 he lost a bid to become one of Nebraska's two U.S. senators when the Republicans took control of the state legislature (at that time senators were still selected by the state legislatures). But he had a crusader's heart, had limitless energy, and a commanding voice that put him on the lecture circuit, where he could spread his message of social reform. A number of issues found their way to the heart of his lectures, particularly the gold-silver crisis (the Panic of 1893) that had the nation deeply divided at that time. As noted previously, when President Cleveland repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, it caused the value of silver to drop away drastically. While this saved the day for America's major industrialists and financiers, it left the American farmers and miners in a terrible situation. Banks wanted payment in stable currency (gold), something that the farmers did not have, especially at a time of greatly reduced food prices caused by the massive production of farm products. Also at the same time, Western miners found themselves simply out of work. The 1896 presidential election

It was Bryan who took up the cause of the farmer and miner, delivering powerful speeches on the lecture circuit attacking the great gain of the rich with their gold strategy.1 Then in 1896 he mesmerized the Democratic National Convention when he delivered his "cross of gold" speech. The speech changed the entire course of the convention, and the young Bryan (just thirty-six years old) was chosen by the Democratic Party (Cleveland was out) to be its presidential nominee for the 1896 national election, running against the Republican McKinley. Bryan then took to the road, to deliver more of his speeches (500), fully expecting this to turn the election in his favor. Of course this election was not just about gold, but also about the huge industrial and financial trusts that controlled the nation's economy, the railroads that practiced monopolistic pricing that crushed the farmer, and the politicians in the pockets of the big-money boys. But the economy was settling down at this point and Bryan did not have the impact that he was hoping for. As we have already seen, he lost to McKinley, gaining 46.7 percent of the popular vote to McKinley’s 51 percent, carrying twenty-two of the less populous southern and western states compared to McKinley’s victory in twenty-three of the vastly more populous states of the Northeast and Midwest and the Pacific coast, and thus taking a beating in the electoral college (271 to only 176). Still, it was a respectable result, so much so that he would become the party’s candidate again in 1900. The question of imperialism and the Spanish-American War

In the meantime, Bryan (like the rest of the nation) got caught up in the growing problems with Spain over its cruel actions taken to suppress rebellion in the remaining Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. Bryan was an ardent anti-imperialist. He considered imperialism to be nothing more than crude bullying, justified by Darwinist rhetoric (which he also detested) about the necessity of the strong dominating the weak. Yet he was himself caught up in the rising democratic Idealism that made democracy the answer to the world's problems. Thus he put aside his anti-imperialism and took up the American nationalist cause of intervening in the Cuban and Puerto Rican rebellion to help those two lands acquire their own democracies – drawing criticism from his anti-imperialist supporters who saw such American involvement as merely another form of imperialism. It also brought sneers from his detractors for his being so confused about exactly where he stood on matters. But then when a piece of follow-up legislation to the Treaty of Paris calling for independence for the Philippines failed to pass in Congress, Bryan began once again to take up his anti-imperialism stance. The 1900 presidential election

Indeed, anti-imperialism was his main theme at the 1900 Democratic National Convention, where Bryan was again chosen to be the party's presidential candidate. Then once again he became a whirlwind of activity, delivering an endless round of speeches denouncing American imperialism – and pressing still for a return to silver currency. Yet at this point the nation had largely moved on past both issues. America was enjoying the Full Dinner Pail, which McKinley reminded Americans that they had come to experience under the last four years of his presidency. Consequently, Bryan's results in his re-match in 1900 with McKinley were an even greater disappointment to Bryan and his supporters than they had been in 1896. At this point Bryan devoted himself to the lecture circuit, especially at the rural Chautauquas that economically-comfortable people attended, particularly in the summers to escape the stifling heat of the American cities. Here whole families encountered a full program of entertainment, sports and cultural exposure. Clearly, Bryan was the most popular of the speakers with his coverage of subjects running from social reform to the Christian faith, especially the latter. One of his favorite subjects was Darwinism and the threat it posed to American morality. He was less interested in the debate raised by Darwinists over the Bible as scientific Truth (the inerrancy issue) than he was in the way the growing Darwinist mindset of modern culture was undermining Christian morality. He even went abroad with his lectures (and just touring) from 1904 to 1906, in a sense taking a vacation from American political issues. The 1908 presidential election

The 1908 presidential election. But when the 1908 election rolled around (and Roosevelt was stepping down from the Presidency in favor of his friend Taft) the Democratic Party again looked to Bryan to run for the presidency. Bryan had a comprehensive Progressivist program to run on, including a constitutional amendment calling for federal government income and inheritance taxes, full disclosure of corporate contributions to political campaigns, the program of the initiative and referendum (citizens having the right to initiate legislation of their own), and more trust-busting. But Bryan just could not excite the electorate with his program, aimed at an opponent (Taft) who himself was a recognized trust-buster, as well as inheritor of the Roosevelt mantle. This, Bryan's third and last attempt at gaining the presidency, brought him even more disappointing results than the two times earlier. It would be his last run for the presidency. Bryan's appointment as secretary of state in 1913

Once again Bryan returned to the lecture circuit. But when the 1912 election came around, he chose to merely support a Democratic Party candidate rather than be that candidate himself. The Convention itself was split among a number of contenders, and finally Bryan threw his weight to New Jersey Governor (and former Princeton University professor and president) Woodrow Wilson, who, with Bryan's support, finally on the 46th ballot was chosen as the party's candidate. Wilson, subsequently elected to the presidency on a mere plurality of votes – because of a split among the Republicans between followers of Taft and followers of Roosevelt – in turn appointed Bryan to the position of secretary of state. Although this was considered the most important of the cabinet positions, actually under Wilson, Bryan would be relegated to a very secondary role in the conduct of the secretary's usual business in foreign affairs – because the idealistic Wilson wanted to conduct American foreign policy himself. But the rest of Bryan's story will be found here in the chapters that follow. 1Bryan

had actually started doing so on the floor of Congress in 1893 when he

was a Representative, opposed to the repeal of the Sherman Act.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges