|

|

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

It is hard today to understand that in the late 1800s and early 1900s imperialism was generally (though there were exceptions) not considered to be some kind of great evil, but was quite the opposite, something able to bring patriotic tears to the eyes of Europeans as they reviewed the blessings brought to the world through their political, economic, cultural or even religious undertakings abroad. As with all aggressive dominators, their ability to rationalize such aggression with high sounding moral logic was truly amazing. But keep in mind that it was the age of Darwin and Social Progress. Darwinism, with its survival of the fittest mentality, made the justification of imperial aggression very natural, even laudable. Newly rising national interest at the heart of European imperialism

Actually imperialism, as practiced in the 1800s and early 1900s, involved simply the transferring away from European and American – or Western – society the naturally aggressive (tribal) tendencies of the West's new, rising and highly ambitious national political actors. This redirection of competitive instincts abroad would help immensely to keep peace within the West itself, for a while – that is until there were no more unclaimed overseas territories available for these hungry empires to grab up. When that happened, Europe fell into suicidal self-destruction: the Great War or World War One. No two nations explained the blessings of

imperialism exactly the same way. But that is because each of these

dominators understood themselves in unique ways, and therefore

moralized their imperialism in unique ways. In other words, there

was no one standard thing called imperialism. It was simply nationalism

written large, nation by nation. The Portuguese

The Portuguese got an early start on (commercial) imperialism in the 1400s, setting out from their Atlantic ports and slowly advancing south down the West African coast, establishing Portuguese trading posts along the way – actually also crossing the Atlantic once the discovery of America occurred and establishing a base point there (Brazil) from which they could then take advantage of the Atlantic currents and sweep back again eastward towards Southern Africa – either way finally reaching the southern tip, the Cape of South Africa. Once around South Africa, the Portuguese then headed toward India, again establishing trading posts – the most notable and enduring being Goa on India's Western coast – and then heading on around India toward the valuable Spice Islands of Southeast Asia. From there they would by the mid-1500s even head north to China, establishing another port along the southern Chinese coast at Macao. They would later lose some of these holdings to the Dutch, but hold on to others, such as Goa and Macao, and their positions in Africa at Angola and Mozambique – well into the 20th century. The Spanish

The Spanish found their way to the wealth of the Far East blocked by the Portuguese, so at the end of the 1400s they headed west across the Atlantic, and in doing so stumbled into the Americas – and a vast amount of gold they were able to acquire in plundering the Aztec and Inca Empires. The wealth was so vast that they had to – and were able to – build a huge navy to protect the transfer of that wealth from the pirates that lurked in the Caribbean waters, where their American empire was headquartered. But their thirst for increasing the number of Catholic souls at a time that Protestantism was driving Catholicism from its religious monopoly in Europe became another key motif of Spanish imperialism. Huge numbers of Catholic priests were sent to establish missions among the new Indian subjects of the Spanish kings, thus bringing Spanish America emotionally as well as materially into the realm of Spanish feudalism. This feudal social-cultural legacy became so well-established that even when these colonies broke free from their Spanish (and closely related Portuguese) sovereigns in the early 1800s, the cultural patterns established through this imperialism remained firmly in place. Indeed, by the late 1800s a romantic revival of Spanish nationalism was taking place in Spain, looking to Spanish America to rebuild the Spanish-Catholic cultural ties that once existed between Spain and America. But Yankee Americans had other ideas. They wanted to democratize this feudal culture, and thus found themselves intervening frequently in the affairs of their neighbors to the south, under the principle of the Monroe Doctrine. These interventions (usually by the U.S. marines) helped support U.S. economic interests in Latin America, but had little impact on the political culture of the region, producing instead a lot of anti-Yankee resentment. The Dutch

While the Portuguese and Spanish were busy setting their overseas empires in place, the Protestant Dutch were busy fending off the very-Catholic Spanish kings trying to force the Dutch provinces back into submission to Catholic Spain. The effort drained Spanish power considerably,1 and instead strengthened Dutch power and resolve all the more. When Spanish power became feeble enough in the early 1600s, the Dutch then headed out on their own to explore the larger world – mostly following the Portuguese imperial route, seizing Portuguese ports along the way: notably South Africa and the Spice Islands (modern Indonesia). The Dutch also established trading posts in North America at the mouth of the Hudson River and the land behind it, on various islands in the Caribbean, and on the northeastern coast of South America at Suriname. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch Empire was largely commercial (trading in valuable goods) in nature, which included a vast number of Africans sold into slavery in order to work the highly valuable sugar plantations in the Caribbean and at Suriname. The British

Early British imperialism followed the pattern of the Portuguese and the Dutch, especially the Dutch with whom the English found themselves in deep commercial competition – with several wars fought in the process. Like the Dutch, the English were early capitalists, forming joint-stock corporations to amass the amount of investment money needed to pay for very expensive private business operations (meaning, not funded by the monarchy). A number of companies reached great size, such as the Muscovy Company in 1555, trying unsuccessfully to reach China by way of a Northeast passage across the arctic, or at least across Russia. And there was the East India Company, though as with all business enterprises, it had its ups and downs. The British East India Company reached such enormous size that it became almost a government in itself, securing political as well as economic dominance over most of India and parts of China. After American independence – achieved through a rebellion sparked in part by the British king's attempt to establish an East India Company monopoly in the tea trade with the American colonies – the British Empire and the East India Company became almost one and the same. The focus of the Company's activities was India, a huge sub-continent over which the Company secured political control through an array of separate agreements with various local Indian lords or rajas. In essence the Indian rajas agreed to place themselves under the Company's protection in order to facilitate the all-important trade of tea, cotton, indigo and salt from India in exchange for the finished textiles of England. Backing up this arrangement was the Company's own private army made up of local Hindu and Muslim mercenaries – or sepoys – commanded locally by some of the rajas, but ultimately by Company officers themselves. It was all quite a noble arrangement for many Indians and Englishmen. The Company and its army was an aggressive player in the international theater, fighting wars here and there in Asia, such as the one waged against the Chinese Emperor – who tried (unsuccessfully) to stop the Company from selling its highly profitable opium to his Chinese subjects. In essence the Company was the world's first major drug cartel! But troubles with its own Indian sepoys developed over the thoughtlessness of some of its English officers, and a huge rebellion resulted (1857-1859) – involving the death of large numbers of English officials and their families serving in India. When the rebellion was finally put down, British Parliament liquidated the Company and took over its affairs directly, creating officially the British Empire – with Victoria now serving as the Empress of India as well Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland (along with many other titles). These were the glory days of British imperialism. And the British Empire stood at the very heart of the whole European imperial system as its proudest symbol. The French

Not to be outdone by the English, the French sought a similar imperial status during the mid-1800s under the new French Emperor, Louis Napoleon or Napoleon III (nephew of the famous Napoleon of the earlier 1800s). The French were having a hard time emotionally with the fact that French culture had once (during the 1700s and much of the 1800s) been a central part of the culture of Europe's ruling classes, and that its decline in the face of rising linguistic nationalism in Europe was a major blow to French pride. France's imperial mission therefore seemed to be to compensate for this loss by taking French culture abroad, trying now to plant French culture among the ruling elite in French Indochina of Cochin China (Vietnam), Cambodia and Laos and at various points along the African coast. The scramble for European imperial territory in Africa and the Middle East Then when in the latter part of the 1800s the Europeans began to take an interest in laying claim to the material wealth (and the souls of the people) in the dark unknown of interior Africa, the French made a huge effort to plant widely the French imperial flag there. Also Egypt – at least since Napoleon's invasion there in the early 1800s (an unsuccessful effort to block Britain's passage from the Mediterranean to India) – had long held French interest, and the French worked out a deal with the local king to build a canal at Suez, which then stirred British interest in the project. The British eventually bought out the king's interest in the Suez Canal, making European imperialism in Egypt at the very heart of the world of Islam a matter of cooperation between both the French and the English. Africa. Also interested in Africa were the recent arrivals on the European national scene, the Germans and the Italians. The many Italian city-states and regional kingdoms had finally united into a single Italian state in 1860, and much the same was the case for Germany in 1870. Now fully national as Italy and Germany, both new countries wanted a piece of the imperial action in Africa – because that was about the only part of the earth that had not already been laid claim to by European imperialists. The Portuguese, of course, were already in Africa (coastal Angola, Mozambique and other small positions along the coast being under Portuguese control since the 1400s and 1500s). And Spain was interested in the North African land across the Straits of Gibraltar (and British-held Gibraltar itself) in Morocco. And America had protectorate responsibilities over the tiny country of Liberia, set up as an independent country to receive American Blacks freed from slavery and returned to the African "homeland" earlier in the 1800s. The decaying Ottoman or Turkish Empire. Then at the same time there was the matter of the Ottoman or Turkish Empire, a great Islamic domain at the eastern end of the Mediterranean and in Southeastern Europe (the huge, multi-ethnic Balkan Peninsula). The Ottoman Empire had lost considerable energy since its glory days in the 1500s, and like old Christendom, it was falling apart. Thus various newly emerging national groups, principally the Bulgarians, the Greeks and the Serbs – once part of the Ottoman empire – were moving to grab chunks of the Ottoman holdings in the Balkan Peninsula in order to establish their own national independence. Meanwhile the English and French busied themselves attempting to grab the rest of the Ottoman Empire – from Egypt to Syria – with the Russians coming at the Turks along the northern coast of the Black Sea at Crimea and Southeastern Ukraine (with the British actually attempting to help the Turks hold off this Russian expansion). The Berlin conferences (1878 and 1884-1885)

All this activity – focused on the dying

Ottoman "Sick Man of Europe" plus the opening up of Africa – threatened

to bring the aggressiveness of European imperialism much too close to

home for the comfort of the major European players. Indeed, since the days of Napoleon's defeat in 1815, there had been a rather high level of diplomatic cooperation among Europe's imperial contenders, sort of a gentlemanly sharing of the spoils of imperialism. The ruling dynasties understood the importance of being somewhat cooperative in their aggressions. They had learned some hard lessons from the Napoleonic wars and had devised a system (the Concert of Europe) to bring their mutual tensions under discussion in order to keep those tensions from pushing them to war, and thus having to call on their people once again to come rescue their thrones from their enemies. And thus it was that they gathered in Berlin in 1878 to come to an agreement as to how they wanted to divide up the dying Ottoman Empire, and assign Ottoman land to the various European participants, notably the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs. Everyone was mostly happy with the results – except the Turks, of course, whose nationalist fever began to rise in the face of this assault on their long-standing Empire. Then in 1884-1885 the Europeans met again in Berlin, this time to get out a map of Africa and assign pieces of the continent to the conference's various European participants. Everyone was a winner (except the Africans, who were not consulted on the matter). The Portuguese were simply confirmed in their old African holdings. The French received major pieces of West Africa (interspersed with English holdings). The Belgian King Leopold was awarded the rich center-piece of Africa, the Congo, as a personal feudal domain, serving somewhat like Belgium itself as a buffer territory designed to keep any one of the major European powers from establishing a single line of dominance across the continent. The English were accorded vast pieces of the rest of Africa, most importantly from the Cape Province in the South – taken from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars – north through the Central part of Africa (with Leopold's Congo being the exception), all the way up through the Sudan to Egypt. The Germans finally got lands in Central Africa to the east (Tanganyika) and the west (Kamerun) of the Belgian Congo. And the Italians got a section of Somaliland at the vital juncture between the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Under Bismarck's skillful leadership this

business had all been conducted in a fairly rational fashion. For

Bismarck and for Germany this was all part of the German nation's new

birth, but also its growing sense of importance within the realm of

European political affairs. 1The

disastrous attempt at about the same time (1588) to do the same thing

to Protestant England by sending their mighty Spanish Armada (army and

navy) against the English also drained Spanish power considerably.

|

|

|

American "anti-imperialism" Americans generally identified imperialism only in terms of direct governmental control of one people over another, the very thing America had revolted against when King George tried to pull that on America. Thus it was that at a time when European powers (but also some American politicians) were bragging about the human benefits of their particular brand of imperialism, "imperialism" in the American lexicon generally had become a very sinister word, something to be resisted at all costs – like Satan himself. However, America actually had its own imperialist agenda, although it would have a very hard time recognizing this agenda as imperialism. For America, as was the case for everyone else, its version of imperialism too would be merely reflective of the social priorities and moral imperatives of the nation – such as it held in late 1800s and early 1900s – extended outward to the larger world as part of its naturally expanding power. There were a number of facets to American imperialism. But basically, there were three paths that this imperialist agenda took: Christianity, American business, and democracy. Just like every other nation, America saw these as entirely noble enterprises, and thus tended to identify none of these as imperialism. The Christian mission impetus

The swing of America from the 1800s into the 1900s was a very heady time, unprecedented material progress evident everywhere, the likes of which were more than just spectacular – they were totally unprecedented. Thus it was easy for Christian Americans (and many Christian Europeans) to believe strongly that the End Times (the Second Coming and Final Judgment of the Lord Jesus Christ) was at hand. But was the world ready for such divine judgment? A rush was on, supported by missionary societies of all Christian varieties, to send out workers to reap the harvest of souls in anticipation of the approaching millennium. Especially prominent in this was the Student Volunteer Movement (Protestant, but not belonging to any particular Protestant denomination) which inspired thousands of fired-up students to leave their American college campuses and head out into the world to save souls. Soon supporting them was an equally highly motivated Laymen's Missionary Movement made up of Americans at home willing to support financially this massive missionary effort. And thus, out Americans went, not only

bringing the Christian gospel to Latin American neighbors to the South

but also Africans and Asians to the East and West across the great

oceans. With this supreme effort to be a Light to the Nations, America

was finally fulfilling its long-standing covenant with God. The democratic mission

Closely accompanying this sense of Christian mission was the idea or doctrine of "democracy for all," related to America's long-held belief in grass-roots self-government – increasingly identified as democracy. Democracy certainly appeared to be the natural political accompaniment to the Christian life (as indeed something like that had been since Puritan days). But Humanists were quick to point out that the political ideal of democracy did not depend on the gospel as its primary foundation. Indeed, the effort to spread democracy abroad would soon be carried out quite apart from the Christian missionary effort – as Humanists attempted to demonstrate in taking up the cause of building (Secular) democratic societies abroad wherever, and by whatever means necessary. The Humanist procedure was quite simple: overthrow the authoritarian rule of the traditionalist ruling classes of the various societies abroad, call representatives of the newly freed people into consultation, develop a new constitution (modeled largely after the American Constitution), and hold elections to fill the offices of the new democratic government. With this new democracy in place, America could then take its leave as mentor and supervisor, and head home, leaving the new society to enjoy the bliss of democracy. Again, the American desire to spread democracy abroad would supposedly put Americans in opposition to the imperialist practices of the other members of the imperial circle, because the imperialism of the others was so "imperialistic" (meaning, non-democratic). But it never occurred to an aggressive America that its desire to liberate the rest of the world (such as Cuba and the Philippines liberated from the Spanish Empire in 1898) in order for it to plant there enlightened American constitutional practices, was just as imperialistic as the behavior of the other, self-acknowledged, imperialists.2 In any case, as official government policy, America did not really have much of an overseas agenda during the first half of the 1800s, the nation being so completely absorbed in its aggressive (imperialist) movement at home against the Indian tribes and against Mexico, and then being caught up in its own Civil War. But it would certainly find itself taking up a broader, more global cause, towards the end of that century and into the next. The expansion of the Monroe Doctrine

But actually the policy worked because the British – who did have the power (which other Europeans well understood) to enforce the doctrine – wanted to keep the door of Central and South America open to British trade, and opposed the kind of colonialism practiced by Spain, and France. The Spanish and French brand of colonialism allowed trade of their colonies in America with only the mother country in Europe (a practice called "mercantilism"). Both the British and the Americans were in agreement about keeping Spain – or any other European power – from retaking the former Spanish colonies. These new states had just secured independence from the mother country. The British for economic reasons and the Americans for reasons of political ideology – although later, like the British, for economic reasons as well – intended to "protect" that independence. Americans did not consider the huge intervention of British business in Latin America as being in violation of the Monroe Doctrine, because they viewed imperialism almost completely in terms of the legal matter of who or what officially governed the country, not who did business with it. British business was just that, business, not government, and good business at that. In fact, Americans saw the opportunity to do the same – involve themselves deeply in the economic affairs of their neighbors to the south – without feeling that they were engaged in imperialism any more than were the British. The "opening" of Japan

An eventual effort to expel the Western barbarians was a dismal failure, and then the mysterious death of the Emperor in 1867 brought forward a young Emperor who was determined to begin the transformation of Japan, along Western industrial – and military – lines. The Meiji Restoration had begun. Alaska

The Russians had been moving eastward across Asian Siberia from their base in Moscow since the 1500s, and may have reached all the way to Alaska with a small settlement by the mid-1600s. By the 1700s Russians were fishing the region, trading for the highly sought-after sea otter pelts, and placing more settlements in the coastal region. The Spanish also sent explorers to the region in the late 1700s to defend (largely unsuccessfully) their claims to the entire Pacific northwest of the American continent. Some Russian settlement continued into the 1800s, though slowly because the region did not seem to be a very profitable enterprise for the Russians.

But when the Dominion of Canada brought British Columbia into its confederation in 1871, hopes to link Alaska directly to the United States were blocked permanently. At the time, $7.2 million for what was popularly considered to be a useless piece of territory gained the whole deal the caption "Seward's Folly." Then when in the 1890s a gold rush brought Americans to Alaska in the thousands, the tune changed dramatically. Eventually Alaska would become officially an American "Territory" in 1912. 2Interestingly,

it still has not occurred to Americans, who even today are in the habit

of overthrowing foreign governments with the hope of instituting new

governments in their place, ones that mirror the supposed American

constitutional or democratic model – which even America has moved away

from as it has come increasingly under the governance of an

ever-expanding care-taker bureaucracy and activist judiciary. Vietnam,

Iran, Russia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria and probably even China,

have taught Americans nothing about democracy's dim possibilities in

other unreformed cultures, even as violent – and unsuccessful – as the

effort to institute democracy in these other countries has generally

proven to be. On the other hand, the democratizing of Germany, Japan

and South Korea has taken deep root – but required huge expenditures of

American social assets (brutal war) and a rather deep and lengthy

American occupation to bring about the necessary cultural

transformation that democracy requires for it to be able to exist at

all.

|

|

|

His refusal led to a revolt in 1887, which he was unable to bring under control. At this point Hawaiian politics moved under the patronage of the Hawaiian League, an elite group of wealthy White-American sugar plantation owners and the core of the Missionary party. They forced on the king a new constitution which created an assembly, but also a House of Nobles, which they controlled and which now dominated Hawaiian politics.

There was much debate in Congress about the legitimacy of such an imperialistic move on the part of the United States, and when a Treaty of Annexation was sent to the Senate for ratification it failed to gain the two-thirds vote necessary for approval. Thus the pro-annexation group in Congress reauthorized the move as simply a resolution, requiring only a majority approval in both houses of Congress. Thus in 1898 Congress approved (barely) and McKinley signed the resolution annexing Hawaii, which took effect officially in August of 1898, at about the time that a conflict was breaking out with Spain over its actions in Cuba.

|

Hawaiian Queen

Liliuokalani (younger and older)

|

|

Cuba. Meanwhile, just offshore from Florida, the Cubans were fighting for their independence from Spain, and the Spanish were absolutely determined to give up no more Spanish territory in the Americas. The violence between the two groups thus grew ugly. It was also affecting the huge sugar industry, largely under American domination (almost 90 percent of Cuba's huge sugar exports went to the U.S.). A large number of Americans began to call for U.S. intervention in the Spanish-Cuban conflict. President McKinley however, aware of the complexity of the crisis, instead sought to work with the Spanish government to see how a compromise could settle things down in Cuba. Also, the increasing talk of intervening in the Cuban question was stirring much opposition, coming from the Anti-Imperialist League – including such individuals as Andrew Carnegie, Grover Cleveland, John Dewey, William Graham Sumner, and Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). In the midst of this controversy were the Hearst and Pulitzer newspapers, hyping the issue of the cruel Spanish actions in Cuba against the freedom-fighting Cubans, to increase their New York readership. Consequently, the American warship U.S.S. Maine was sent in January of 1898 to Havana to put a chill on the violence. But then when the next month the Maine blew up and sank in Havana harbor, the newspapers went wild with outrage at the Spanish government for having committed this vile act. A quick official investigation into the tragedy concluded that this was an act of perfidy on the part of the Spanish government.3 With the publication of the findings at the end of March, Americans demanded war with Spain. Less than a month later both sides had declared war on each other. The war in Cuba was of very brief duration, but of great consequence. With the capture of Santiago (via the Battle of San Juan Hill) and the destruction of both the Spanish fleet and army based there at the beginning of July, the Spanish quickly lost their hold over Cuba. The Philippines. But the action also reached all the way across the Pacific to the Spanish Philippine Islands and the Pacific island of Guam. In the Philippines, over 300 years of Spanish rule had been under challenge (much like events in Cuba) since 1896 by a liberal party of Filipinos demanding independence. Thus the position of Spain in the Philippines was very shaky at the time war between America and Spain was declared. Even before action in Cuba had taken place, Americans made their move on the Spanish Philippines. The decision to do so itself was another huge moral stretch, it too being strongly opposed by the Anti-Imperialist League. Thus in late April 1898, as tensions mounted between America and Spain, McKinley spent an evening in prayer, before announcing the next morning that he perceived that it was God's will for America to "educate the Filipinos, and uplift and Christianize them." (But the Filipinos were already heavily Catholic. So what did "Christianize them" actually mean?) Standing in agreement with McKinley was the leading voice of the Imperialist party, Senator Albert Beveridge, who saw the taking of the Philippines as the call of the Divine Father himself on a noble and favored America to take up this mission, this sacred duty in the Philippines. With such a divine duty having fallen on America, on May 1st Admiral George Dewey's fleet moved on the Spanish fleet based in Manila, quickly destroying the Spanish fleet in a single day's action. Troubles then developed when warships from Britain, France, Germany, and Japan showed up at Manila, expecting to participate in the opening of the Philippines. Most aggressive were the Germans who sent numerous warships, having previously expected the Americans to be defeated by the Spanish and thus giving Germany the opportunity to take over the islands. But the Americans were quick to gain control of the islands, finally seizing the capital Manila itself on August 13th – a day after a peace agreement had already been worked out between Spain and America in which Spain simply turned control of the Philippines over to America. Then American cooperation with the

Filipino rebels abruptly ceased when American commanders refused to let

the rebels enter Manila with the victorious American troops. Resentment

flared, beginning a conflict between the Americans and Filipino rebels,

who immediately declared a Philippine Republic. The Americans, however,

were unwilling to surrender their role as "protectors" of the

Philippines, claiming that without American protection, Spain or some

other European power would soon drag the Philippines back under

European imperial control. Besides, America wanted to make the

Philippines a model of democratic creativity – under American tutelage

(of course). But the Filipinos didn't see things this

way. And thus the Philippine-American War broke out in February of

1899, a war that would drag on until 1902 (although guerrilla action

would continue sporadically in the Philippine provinces for ten more

years after that). This war would tragically become much more deadly

(the loss of much civilian life through disease and starvation) than

had been the brief war with the Spanish during the summer of 1898. The 1902 Philippine Organic Act helped settle things a bit, giving the Filipinos limited self-government in the form of a Philippine Assembly, elected by a select section of Philippine society. Eventually, under the urging of President Wilson, the Filipinos were promised future independence with the 1916 Philippine Autonomy Act. 3The actual evidence itself was very inconclusive, and is still under debate even today, although most researchers now think that the explosion occurred from within the ship, possibly from a coal fume (methane gas) buildup, and not from a Spanish mine outside the ship.

|

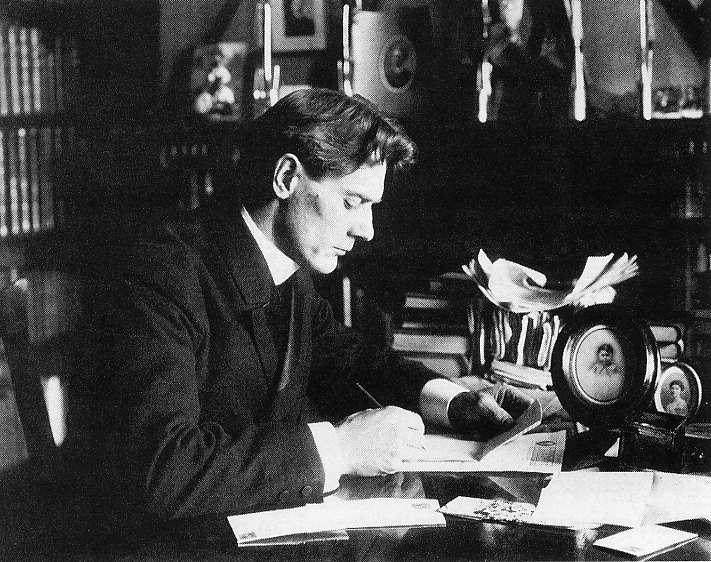

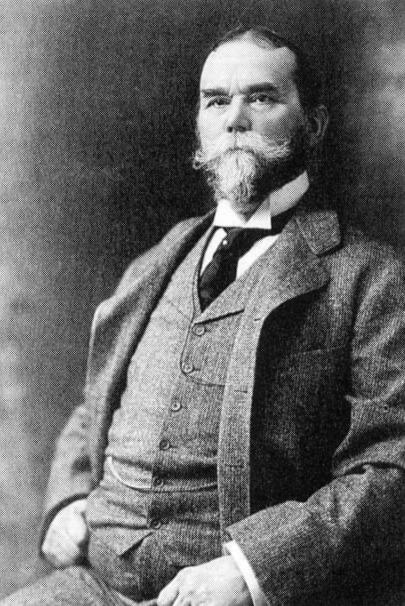

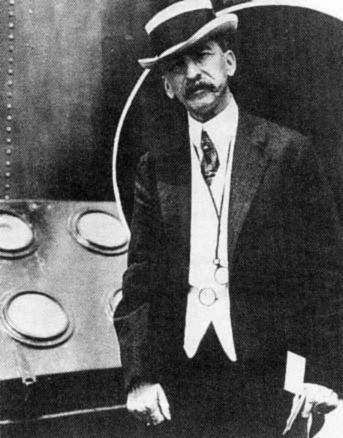

Senator Albert Beveridge

(Indiana) – advocate of American imperialism at the end of the 1800s

John Hay – McKinley and

Roosevelt's

Secretary of State

He was a strong advocate

of the Open Door Policy in China

and the building of the Panama Canal

The pre-text: supporting the independence of Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and the Pacific

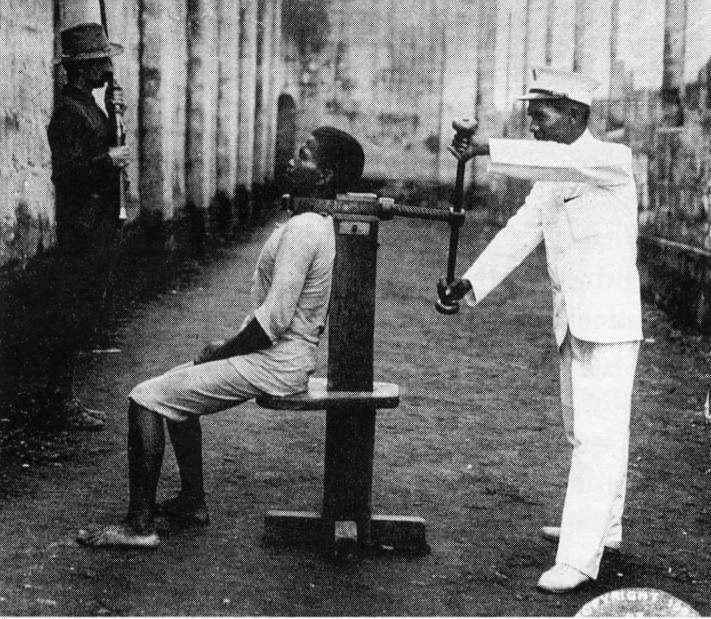

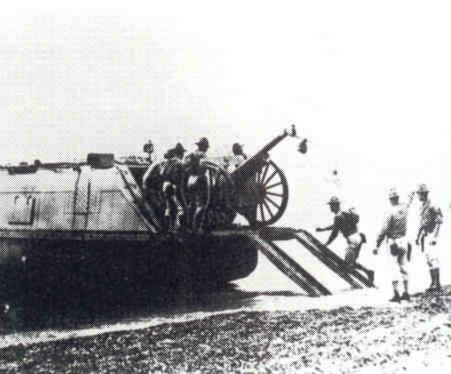

Spanish firing squad (Alphonso

Guards) preparing to execute Cuban rebels

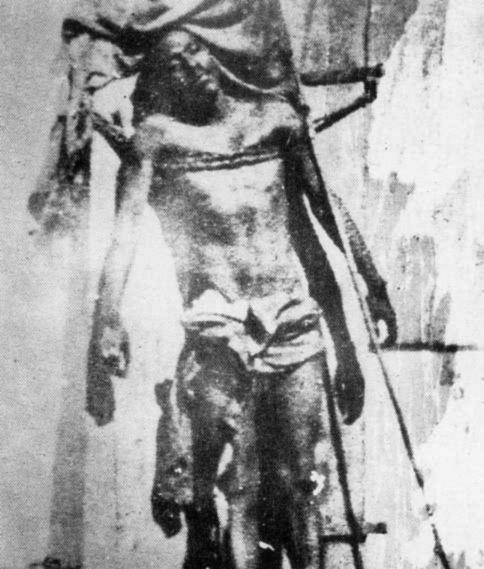

Cuban rebels about to be

executed by the Alphonso Guards

Spanish execution chamber – Manila

The excuse: The unexplained explosion of the Battleship Maine in Havana Harbor

The U.S.S. Maine entering

Havana harbor – January 1898

California troops ready to

leave for Manila – 1898

|

|

The Boxer Rebellion (1898-1901) and its aftermath

From the early 1800s on, the British East India Company had begun the process of opening China to the West, to British trade, in particular the highly profitable and highly corrupting trade in opium. The Company had resorted to this trade in order to recover vast amount of silver coinage that had made its way to China to buy China's valuable porcelain ware (its china!), its silks, its teas, etc., a one-way trade because the British seemed to have no product – except opium – that interested the Chinese in exchange. The Chinese emperor attempted to put a halt to this corrupting opium business, and the company fought back, resulting in two Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860) which worked to the advantage only of the British and to the increasing political humiliation of the Chinese emperor and his people. The second war resulted even in the forced opening of a large number of Chinese coastal ports to European (and American) trade. It also opened all of China to Christian missionary activity, which previously had been limited only to the assigned open ports. Numerous Chinese rose in popular revolt in 1850 against the weakened Manchu or Qing Dynasty, commencing the 14-year Taiping Rebellion, actually a civil war originally between the followers of a quasi-Christian Hong Xiuquan and the failing Manchus. The war savaged China horribly from end to end (somewhere between twenty and thirty million Chinese died in the war, mostly due to the famine and plague that broke out within this greatly weakened society). The Manchus were finally able to regain control of the country in 1864, although rebel armies continued to hold out until the last one was defeated in 1871. A greatly weakened China had no real defenses against the Europeans and Americans who now flocked to China to participate in its trade, its industries, and its religion and education. Little by little the urban areas of coastal China began to take on Western appearances, to the distress of Chinese traditionalists in the interior of China. Cooperation continued to be the general rule in the continuing opening of China by the European imperialists, joined by America, and now also by Japan, which had developed its own modern army and navy and a modern industrial economy to support its modern military. Toward the end of the 1800s, Chinese resentment flared over this increasing domination of their society by these outsiders, especially by the Japanese, who humiliated the Chinese in the Chinese-Japanese (or Sino-Japanese) War of 1894-1895, fought largely over the matter of control of Korea. This humiliation led to a demand by both Chinese modernizers for more reform of the country along Western lines, and by traditionalists – members of the Boxer movement – pressing for a return of China to the greatness of its glorious past. The Boxers were the first to act,

breaking out in rebellion in 1899 against the Manchu Dynasty and

against Westerners, but especially against fellow Chinese who had taken

up Western ways – whom they murdered in vast numbers. Joint action by

the English, Germans, French, Americans, and Japanese (among others)

finally crushed the rebellion (1901).  Destruction resulting from the Boxer Rebellion ... and the Western response

The execution of a Boxer rebel This was followed by the execution (by Japanese swords) of thousands of rebels and the permanent stationing of foreign troops in the Manchu capital at Beijing. It also included the agreement by the Manchu government to send annual indemnity payments to members of the eight-nation coalition, in the amount of virtually the entire annual Chinese governmental budget, over the next thirty-nine years. But at least China was not divided up like Africa and the Ottoman Empire, because of an Open Door Policy put forward in 1899 by the American Secretary of State John Hay – a policy importantly supported by the British. This enabled tradesmen to operate anywhere in China rather than only in designated zones. It also served to preserve the unity of China, pleasing somewhat the anti-imperialist party in the U.S. Congress. Nonetheless the Manchus could not deliver on the agreed indemnity payments, and their government, despite efforts at Western-style reform, finally collapsed, with local warlords now taking over different regions of China. China thus found itself again involved in chaotic civil strife. This in turn moved the Chinese modernizers or Nationalists (the Kuomintang) in 1911 to depose the last of the Manchu emperors in an effort to establish a Chinese Republic. However a political mishap occurred along the pathway towards republican government when, in the process of trying to bring Chinese warlords under control of the new republican government, Nationalist Army General Yuan Shikai came close to establishing a personal dictatorship. He died however in 1916, ending this problem, but increasing the ability of the warlords to operate even more independently of the republican government. It would take a massive effort on the part of the Kuomintang and the skillful leadership of Dr. Sun Yat-sen almost ten more years to bring the warlords under some degree of control by the Chinese Republic, although even then not fully so.

|

|

|

Negotiating an end to the Russo-Japanese War (1905) It was Roosevelt that truly brought America into the game of international diplomacy as a major power broker. In 1905 he hosted in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a peace conference to help the Russians and Japanese work out a settlement ending their war fought along the Eastern coast of the Pacific (it had cost the Russian army and navy dearly and the Russian Tsar his standing in the hearts of his own people). The skillful diplomatic negotiator Roosevelt balanced the interests of both sides in such a way that a final settlement would cause Russia the least amount of loss of face, yet give Japan the recognition as a rising power that it so eagerly sought. Roosevelt had no idealistic cause of his or America's own to pursue in this matter. Yet the action brought notice to the world that America was actually much more sophisticated politically than they had previously believed (America was still believed by Europeans to be merely a land of cowboys and Indians). And it also brought Roosevelt in 1906 the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation ending the Russo-Japanese War.

Helping resolve the Moroccan Crisis (1906) Also Roosevelt was personally present at the Algeciras Conference in southern Spain which was called in 1906 to resolve a growing naval confrontation between Germany on the one hand and Britain and France on the other over the status of the still somewhat independent Sultanate of Morocco on the North African coast just opposite Spain. Roosevelt threw America's weight to the British and French side, helping to force Germany to back away from a needless confrontation, one that looked as if it might lead to all-out war if allowed to continue.4

4Unfortunately,

the settlement only postponed the conflict; it reappeared in 1911 –

which again was negotiated to a standoff – and then in 1914, at which

point all parties involved lost complete control over events (the

startup of World War One).

|

|

|

America had long looked at the necessity of

connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the narrow strip of land

constituting the southern portion of Central America. The French jumped

at the opportunity first, signing an expensive deal with the Colombian

government to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama – but had to

drop the project because of the way malaria kept striking down their

workers. Politicians in Washington in the meantime had been looking at

the possibility of building a canal across the wider, but flatter

expanse at Nicaragua. The French anticipated this move by offering to

sell their Panama Canal rights cheap, and helped to move things along

politically (Panamanian independence) when the Colombian Senate refused

to accept the transfer. Thus America took up the project in 1904 with the newly independent government of Panama, first solving the malaria problem (mosquito control and vaccinations) and then putting their heart and soul into the massive digging involved. For Roosevelt, this became a chief project of his, however not being able personally to complete the project during his presidency (ending in 1908) but following closely the progress on the project until its completion in 1914. |

Digging the Panama Canal – 1904-1914

Digging the Panama Canal – 1910

The Culebra Cut in the Panama Canal

Mammoth Locks being built at the Panama Canal – 1912

|

|

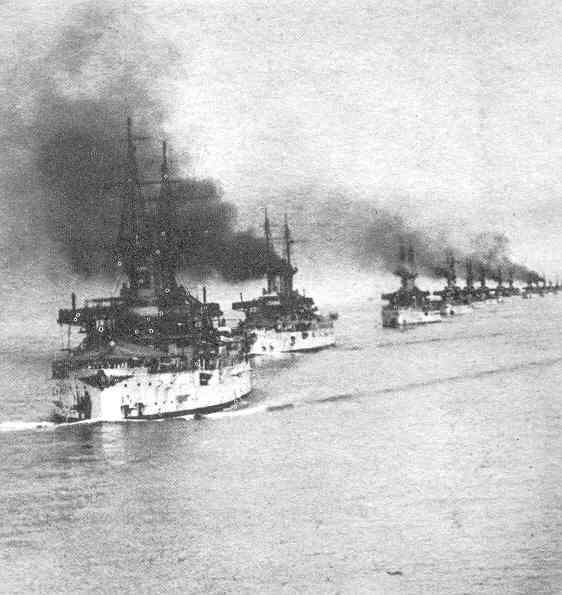

Roosevelt, who was entranced with naval power as

the underpinning of national greatness, decided in the very last year

of his presidency that it was time for America to demonstrate that

greatness5 by sending

sixteen new battleships of the U.S. Navy around the world. There were

many hurdles that had to be crossed to get this operation underway: the

lack of coaling stations needed to refuel the ships' engines, the fact

that the Panama Canal was not yet completed, and the opposition to the

plan by congressmen who thought this all to be a needless government

expense. But Roosevelt forged ahead anyway, had the hulls of the ships

painted white (thus the name for the fleet), and sent them on their way. 5Not

just to the great European powers but also the Japanese who, having

just humiliated Russia in their naval war in East Asia, seemed to pose

something of a challenge to America and its position in Asia achieved

through the Spanish-American War.

|

President Roosevelt sends

off the Great White Fleet in its round-the-world trip – December 1907

Teddy Roosevelt's "Great

White Fleet" of 16 battleships and 15,000 sailors

sent on a 14-month global

tour in 1908 to announce America's entry into world affairs

US sailors, part of the Great

White Fleet" world tour, being greeted in Japan – 1908

|

U.S. marines landing artillery

in Haiti – 1915

The body of Haitian rebel

leader Charlemagne Massena Peralte – killed by US-led gendarmes

|

Mexican President Francisco

Madero

The first democratically

elected leader (1911) in Mexico's history.

He is announcing a plan

to transfer the wealth of Mexico

from the wealthy aristocrats

and foreigners to the Mexican people themselves.

General Victoriano Huerta

(center) in early 1913

overthrew the Madero government

(murdering Madero in the process).

Augustin Victor Casasola

/ Casasola Archive, Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico

City

|

Behind the plot was the U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson representing the interests of the aristocrats and foreigners who traditionally had run the country. (American business interests controlled 43 per cent of the country's wealth – notably nearly all the mines and smelters and two-thirds of the railroads; other foreign interests – notably British and German – controlled another 25 per cent; and the remaining wealth was controlled by one per cent of the Mexican population).

|

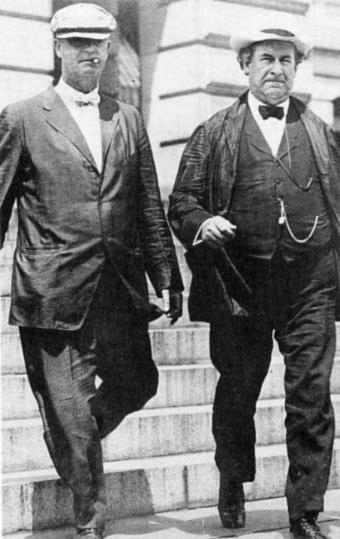

Henry Lane Wilson,

U.S. ambassador to Mexico

Wilson's Secretary of State,

William Jennings Bryan (and bodyguard)

Harry Ransom Research Center,

The University of Texas at Austin

| Bryan supported Wilson's idea of forcing the Mexican dictator Huerta out of office (a large expeditionary force of U.S. troops landed at Veracruz in 1914 and achieved Huerta's resignation); a year later when ranking members of the U.S. State Department plotted to overthrow the new Carranza government – and put Huerta back into office – Bryan moved to bloc the plot. Huerta was seized at the Mexican border and imprisoned in Texas. |

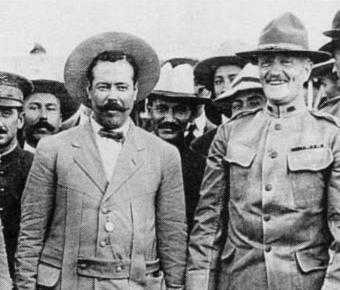

"Gen. Villa, Mexican

bandit"

"1. Gen. Fierro. 2. Gen. Villa.

3. Gen. Ortega. 4. Col. Medina." – ca. 1913. – W.H. Horne Co

Pancho Villa and his rebel

army on a raid along US-Mexican border – 1916

Pancho Villa and US General

John Pershing in happier days – 1914

Headquarters of the

American forces in Colonia Dublan, Mexico.

General Pershing with his

aide Lt. Collins – 1916 – photo by William Fox.

"En route with the American

Field Headquarters from El Valle to Las Cruces, Mexico,

April 10,1916. Company A,

6th Infantry, in emergency trench which has been prepared

at its camp for Attack by

Mexicans." – photo by William Fox.

"A triple execution at Juarez,

Mexico, about the time of the Columbus affair" – ca. 1916

photo by W.H. Horne

Co.

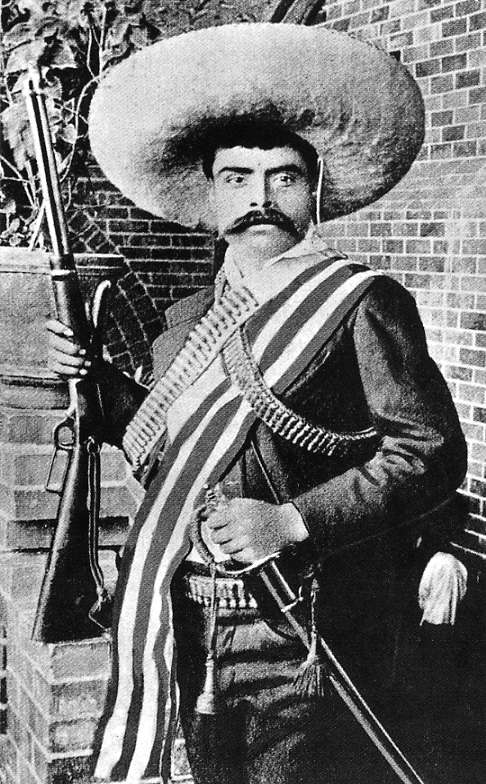

Emiliano Zapata – rebel leader who took on the wealthy landed gentry of Mexico

Miles H. Hodges