|

Meanwhile, Europe also struggles to find its way forward

Despite the Idealism of many of the European

leaders, especially those of Great Britain and France, the mood of the

average European was not all that different from the average American,

rural or urban.

For Europeans, who had suffered greatly

through the four years of war, the post-war period was troubled with

the thought that all of the war's high-sounding nationalist spirit had

produced in the end only mindless death and destruction. A spirit of

disillusionment with politicians and cynicism with respect to their

ideas and programs set in, much as it did in America.

This cynical spirit stirred a sense of

political opportunity among a number of extremist political factions

and their leaders: Communists and Social Democrats on the Left and

Fascists on the Right. They found their appeal strongest among the

social classes that had suffered most from the crumbling of the older

social order.

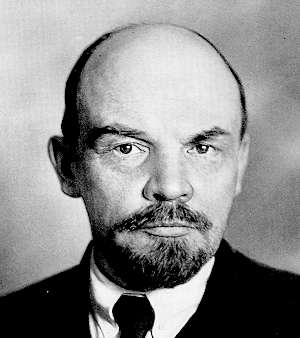

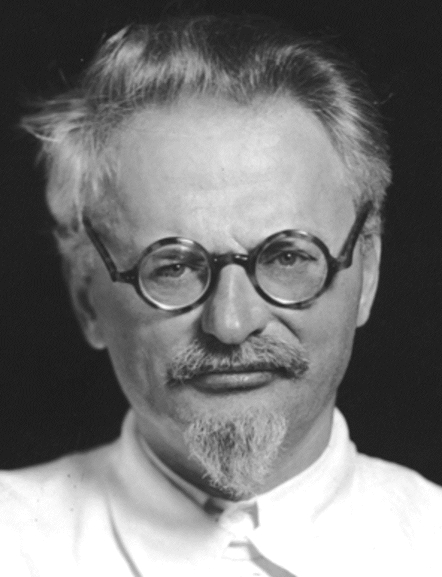

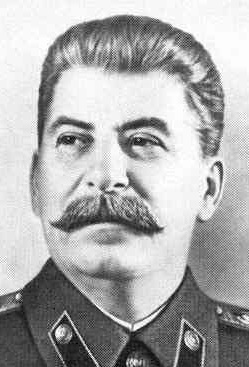

Socialism/Communism.

European soldiers coming out of the war found that with the war over

and war-time industry cutting back, jobs were scarce, and the ones that

did exist paid very poorly. They were deeply resentful of the way their

personal sacrifices were so poorly rewarded – while fat-cat wartime

industrialist owners or capitalists still seemed to be doing fairly

well for themselves. This group of industrial workers was thus easily

manipulated by leaders who urged the workers to rise up against the

wealthy industrial property owners, seize their property and make it

communally their own. This was the basis of the Communist appeal which

produced workers’ uprisings all across Europe in the 1920s (and the

huge Red Scare in early 1920s America).

Fascism.

Other European soldiers, upon a return to their farms, found that they

had been left behind economically and culturally by developments

brought on by the war. With international farm prices running at a new

low, farmers found it difficult to sustain a living for themselves and

their families. They watched with resentment as a fast-growing urban

industrial order appeared to be enjoying many of the new economic

opportunities of the post-war world. This agrarian/ small-townsmen

group was easily manipulated by leaders who stressed the importance of

restoring a largely romanticized traditional agrarian social order.

They promised to bring the glories of a mythical past back to existence

– if the people simply surrendered their hopes and dreams to the total

management by their great leaders. This appeal is the basis for what

will come to be called Fascism.

European Fascism actually had its roots in

Italy when post-war Italy seemed literally to have fallen apart

politically. Although Italy had finally joined the war in 1915 on the

"victorious" side in the Great War, there had been nothing at all about

Italy’s performance in the war to indicate to the average Italian that

they had achieved anything at all of what might be classed as victory.

Instead, coming out of the war, the Italians generally considered their

former leaders as grand failures – which the Italian leaders themselves

understood was their political standing in Italy. Thus they tended to

lay low. And thus also a power vacuum existed in Italy after the war.

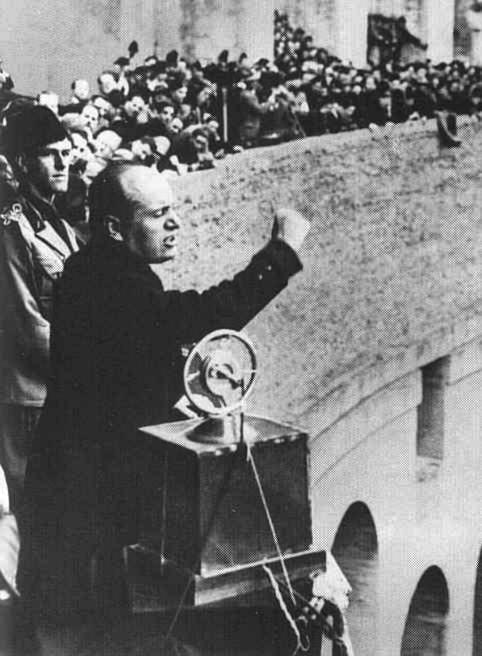

And into that vacuum had stepped Benito

Mussolini, the bombastic editor of a Milan newspaper. Mussolini had

started out as a Socialist propagandist – who turned against Socialism

when it refused to support the Italian entry into the Great War.

Mussolini saw the war as a means of bringing Italy to a new strength

and prominence: strength through collective struggle (Fascism).

Mussolini became bitterly opposed to Marxist Socialism, with its call

to European workers to resist taking up arms on behalf of capitalist

war profiteers – a call which Europe’s fiercely nationalist workers had

largely ignored … and then had paid a huge price for their patriotism.

But Mussolini was opposed not only to

Socialist pacifism, he was as opposed to Liberal Idealism with its

hopes to build an international order of peace through a new spirit of

international democratic cooperation. Mussolini accused such

philosophies of peace as merely weakening human strength and producing

effete societies. He exalted strength – strength through conflict,

strength through struggle – which would produce a warlike character

among a people. This in turn would bring them to greatness – greatness

such as the ancient Romans had once exemplified. The key to this

process was achieving an absolute unity of the people through

unswerving loyalty to a great leader, a Duce (Italian simply for

"Leader") such as Mussolini himself proposed to become. He promised

Italians (notably Italy’s industrial leaders) to bring unity to Italy

through a policy of strict enforcement of social conformity through the

use of his street toughs (the Fascist Blackshirts) – who stood ready to

strike total fear in the hearts of labor agitators and anarchists

through whatever means necessary to do so.

At a time when Italy seemed to be

threatened internally by the same forces tearing Russia and Germany

apart, this Fascist call of Mussolini's to enforced unity had a very

strong appeal. Thus it was that in October of 1922 a small group of

Mussolini's Fascists marched on Rome – facing virtually no resistance.

The Italian king responded by asking Mussolini to save the nation by

becoming its leader. Italy now began to head down the path of Fascism –

forced national unity under the domination of the Duce, who was to do

the thinking and direct all the actions of the Italian nation. Any

resistance to his program, actively or even just verbally, was met with

stiff repression.

|

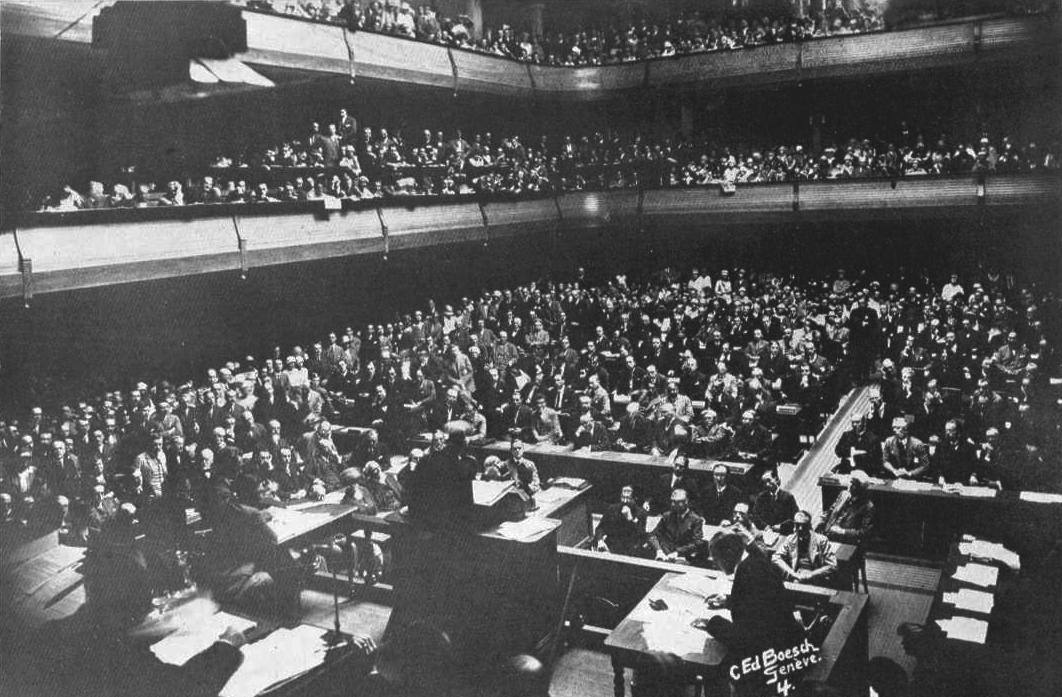

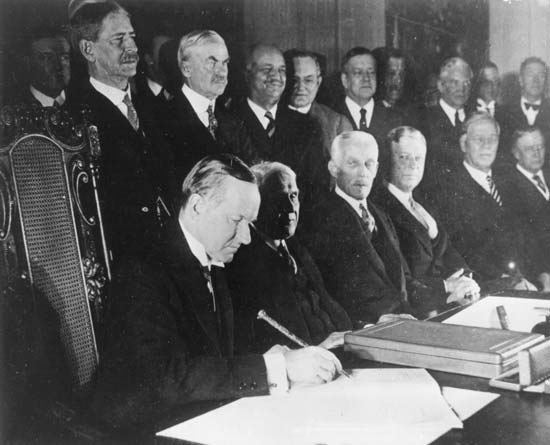

The League of Nations: Wilson's utopian project

The League of Nations: Wilson's utopian project America's approach to

the larger world of global

diplomacy

America's approach to

the larger world of global

diplomacy The court martial of General Billy Mitchell

The court martial of General Billy Mitchell European political

developments lead the world in the opposite direction

European political

developments lead the world in the opposite direction

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges