|

|

Occupation and demobilization of Japan Occupation and demobilization of Japan Occupation and demobilization of Germany Occupation and demobilization of Germany The Europeans struggle to survive and dig out The Europeans struggle to survive and dig out The peace treaties with the other former enemy nations The peace treaties with the other former enemy nations The new United Nations wants to put in place a peaceful world order The new United Nations wants to put in place a peaceful world orderThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 53-56. |

|

|

|

World War Two was devastating

for both the Allied and Axis nations.

Five countries suffered

the deaths of more than 10% of their population.

Wikipedia – "World

War II"

|

Taking over the former Japanese Empire

The situation in Asia and the Pacific at the end of the war was fairly straightforward. The Americans, the Chinese, and the British and their Commonwealth partners (Australia and New Zealand) were largely of one accord on matters; the Russians entered too late to have much to argue about (though they did get quite a nice compensation for a week's worth of wartime effort!); and the French and Dutch were so enfeebled by the war that although they wanted to hang on to their empires in Southeast Asia, they could bring little muscle to the effort. A major question that hung over Japan in defeat was what to do with Japan's wartime leaders, considered widely among the Allies as international criminals. Most critical of all was the matter of the status of the Emperor Hirohito. Many Allies felt that he was especially guilty of war crimes because of his guidance and support of the Japanese military that had assaulted and plundered Asia and the Pacific. But Truman (as well as the American commander General Douglas MacArthur) understood that governing a post-war Japan would be very difficult without the cooperation of local leadership, in particular the emperor. Thus MacArthur headed off investigations destined to implicate the emperor in war crimes. Indeed, MacArthur stood strongly with the emperor in redirecting his place in Japanese society away from his former god-like status, to a status more akin to Europe's constitutional monarchs. And the emperor was himself willing to switch to this new role, presenting himself before the public at various events, even taking walks through the streets of Japan's cities and towns to meet his people personally. The Japanese themselves seemed to be quite okay with this change in the character of their government, and indeed seemed to switch rather quickly from a dedicated hostility to America and things Western, to a willingness to adapt to and even learn from their new occupiers. Consequently, Japan made the transition to the post-war world without the major traumas that much of Europe encountered. Another factor in the smooth transition was American General MacArthur. He had previously spent considerable time along his career path operating within Asian culture, and possessed an important amount of knowledge about Asian culture and its priorities. Thus he himself easily took up the role Asians expected of their leaders: noble, strong in will, and with an obvious concern for the welfare of the society. In a way, Japan now had two emperors: Hirohito and MacArthur, who worked well together.

|

Devastated Hiroshima -

1945

U.S. Air Force

In the background, a Roman Catholic

cathedral on a hill in Nagasaki. ca. 1945.

National Archives

77-AEC-52-4459.

MacArthur arrives in Yokohama,

Japan – August 30, 1945

American GIs playing softball

with a Tokyo team in October 1945 –

only two months after the

end of the war

U.S. Army

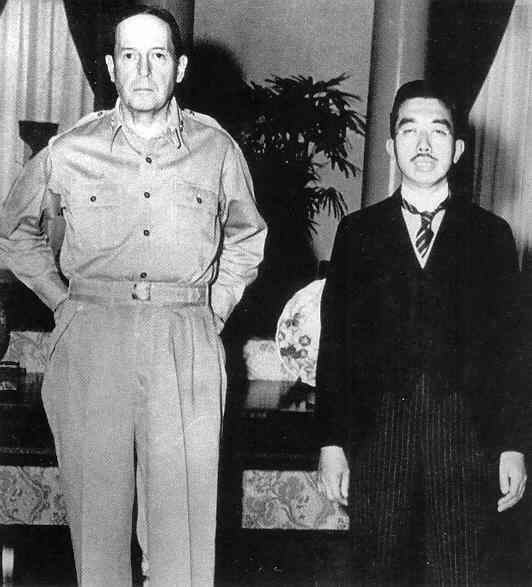

Supreme Commander Douglas

MacArthur and Japanese Emperor Hirohito – 1945

National Archives

NA-208-N-46403-FA

The man once considered a

god, Emperor Hirohito, meets with residents of a new

housing project near

Tokyo – part of the

democratization

of Japanese authority

U.S. Army

|

|

The dividing of Germany

At the Potsdam Conference, the new German boundaries broadly agreed on at Yalta earlier that year had been finalized. Poland was awarded much of Germany's eastern lands (all the way west into the German heartland to the Oder and Neisse Rivers), given to Poland as territorial compensation for the eastern lands of Poland seized during the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, which were now formally recognized by the Americans and British as being permanently annexed to the Soviet Union. Additionally, much of old East Prussia (the heartland of the ancient German Teutonic or Prussian state) was divided in half, with the northern portion and its leading city of Königsberg given to Russia and the southern half to Poland. Also the German free city of Danzig was turned over to Poland. Germany itself, or what was left of it, was divided first into three zones, one in the East placed under Soviet supervision, one in the Southwest under American supervision, and one in the Northwest under British supervision. France wanted a zone in the West, bordering Germany, and Russia agreed to reworking the boundaries of the zones – as long as the French zone was drawn entirely from the British, and American zones. So it was that France also became an occupying power. The Berlin capital city, which was located entirely within the Russian zone of occupation, was itself divided also into four sectors: Soviet, French, British, and American. The Russians promised free access from the American, British, and French zones in the West through the Soviet zone to Berlin. As events would soon prove however, that would leave Berlin – even the sections of the city under joint French, British, and American control – in a very vulnerable position. Learning of these territorial transfers, masses of Germans living in East Prussia grew fearful of what would happen to them under their new Polish and Russian masters, and filled the roads as they fled west to what was left of Germany, even then trying to reach past the eastern or Russian sector (what would soon come to be called East Germany) in order to get to the West German (the American, French or British) sectors of a newly divided Germany. Hunger and intense suffering (even death) from winter exposure became widespread among a huge German refugee population. The Germans, however, expected little sympathy from the rest of Europe. They were on their own to face their new fate as fallen Übermenschen.

|

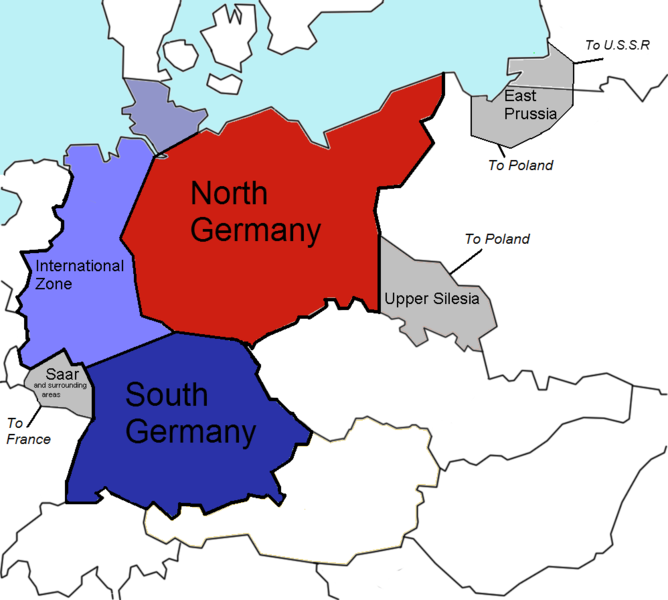

The Morgenthau Plan showing

the planned partitioning of Germany into a North State,

a South State, and an International

zone. Areas in grey are areas intended for

control by France, Poland

and the USSR.

Wikipedia – "Allied-occupied

Germany"

Official map from 1945 showing

the Allied allocation of the occupied German territories.

Text is in English and German.

The territories east of the Oder-Neisse line

that were granted to Poland

are here described as "Polish territory"

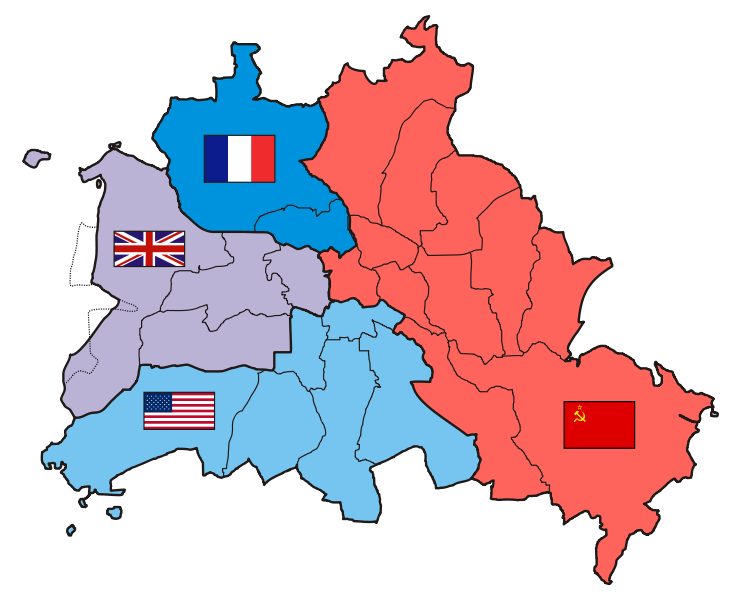

The four sectors of the occupied

Berlin

Wikipedia – "Allied-occupied

Germany"

Workers removing the sign

from a former "Adolf Hitler Street"

Demonstrating American G.I.s

marching down the Champs Elysees in Paris

demanding to be sent home

- January 1946

Devastated Nuremberg -

1945

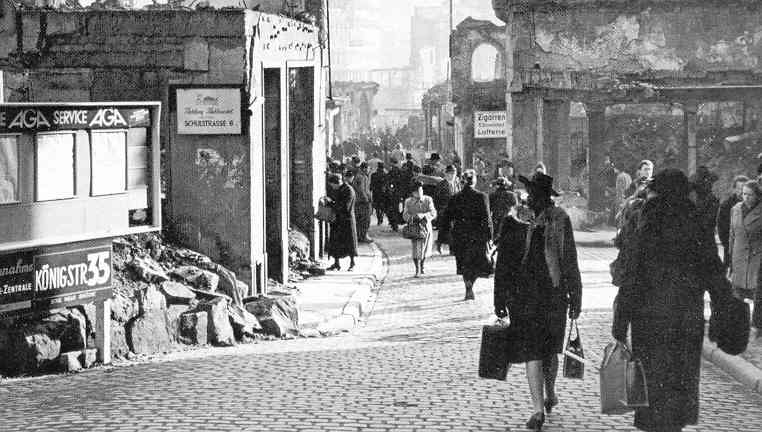

Cologne in ruins

Bremen, Germany at War's

end – 1945

US Army

Bombed-out Dresden – May

1945

|

Bringing justice to the Allies' former enemy leaders

A major issue facing the victorious Allies was what to do with the leaders of the former Fascist enemies. To a great extent the Italian situation had resolved itself when in late April Mussolini was captured by Italian anti-Fascists (for the second time) and this time shot and then hung up (along with his mistress and a number of his close supporters) for display in a public square in Milan. Hitler had also resolved the question of his fate when at the end of the month he and his long-time mistress, Eva Braun, committed suicide. Also Himmler and Goebbels (and family) had taken the path of suicide. But twenty-four other leaders were arrested and turned over to a special court located at Nuremberg. After lengthy hearings begun in November of 1945, on October 1st, 1946, judgements were handed down: twelve were to be hanged (Air Marshall Goering had hanged himself in his cell just prior to the sentencing; Labor Front head Ley had done so several months earlier), seven were given lengthy prison terms (three for life) and three were acquitted. With this, it seemed that the Allies were ready to move on with their work of reconstituting Germany. Russia was given the go-ahead within its occupation zone in East Germany to strip the land of any and all German industrial equipment it needed in order to rebuild its own war-torn industrial infrastructure. At first Russia was rapid in the dismantling of German industry, although the Soviets eventually slowed down the process when it became apparent that ruining the German economy would leave Russia facing a huge social crisis in Russian-occupied Germany, a crisis that Russia was not ready to handle. Meanwhile in their zones, the British, French, and Americans also undertook to dismantle the German armaments plants, but also slowed up the process when they discovered the same problems the Russians had encountered. Indeed, in the French zone, gradually farming, coal mining, and steel manufacture were encouraged by the French administration, since much of the production and profits were directed toward France.

|

Nuremberg War CrimesTrials: looking

down on the defendants' dock. Ca. 1945-46.

National Archives

238-NT-592.

Göring, Hess and Dönitz hear their sentences - September 30, 1946

|

Black-market trading between

soldiers and civilians – Berlin Tiergarten – summer 1945

Cameras, household goods

and heirlooms were traded for money or cigarettes –

to then purchase scarce

food

Berliners looking for anything

of value that can be used for barter

Citizens of Dresden sorting

out useable brick and stone as a volunteer effort to rebuild Germany

A woman in Nuremberg in a

makeshift home cooking a mix of apples, potatoes and greens

Makeshift life in

Hamburg

Imperial War Museum,

London

A small group of German women

and children arriving in the British sector of Berlin,

October 1945 – the sole survivors of 150

who were expelled from Lodz, Poland, 270

miles away. The mother in front is striding

out ahead, anxious to get help for her

3-year old son.

The mother clasps the son to keep him warm – and then realizes that her son has just died.

The women grieving as the

boy's head is pillowed on a railroad track

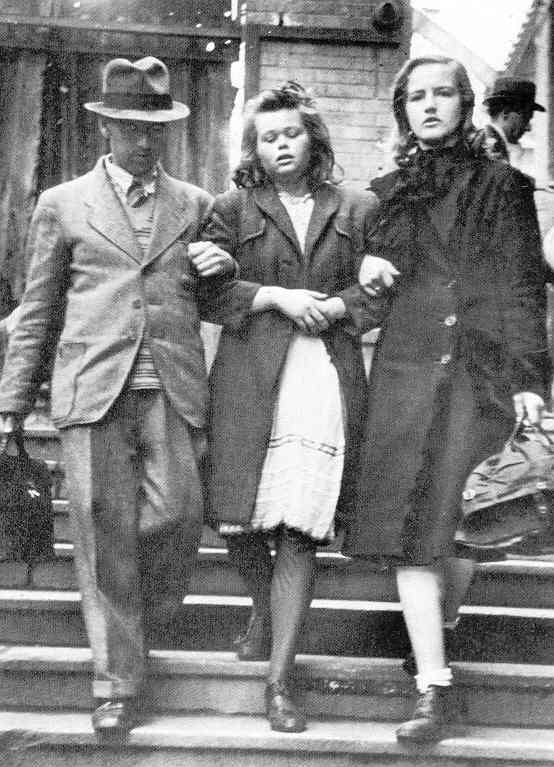

A German girl being led from

a Berlin train station –

having been gang-raped by

Polish youths (typically, war orphans)

who regularly boarded trains

to rob or rape German refugees fleeing Poland

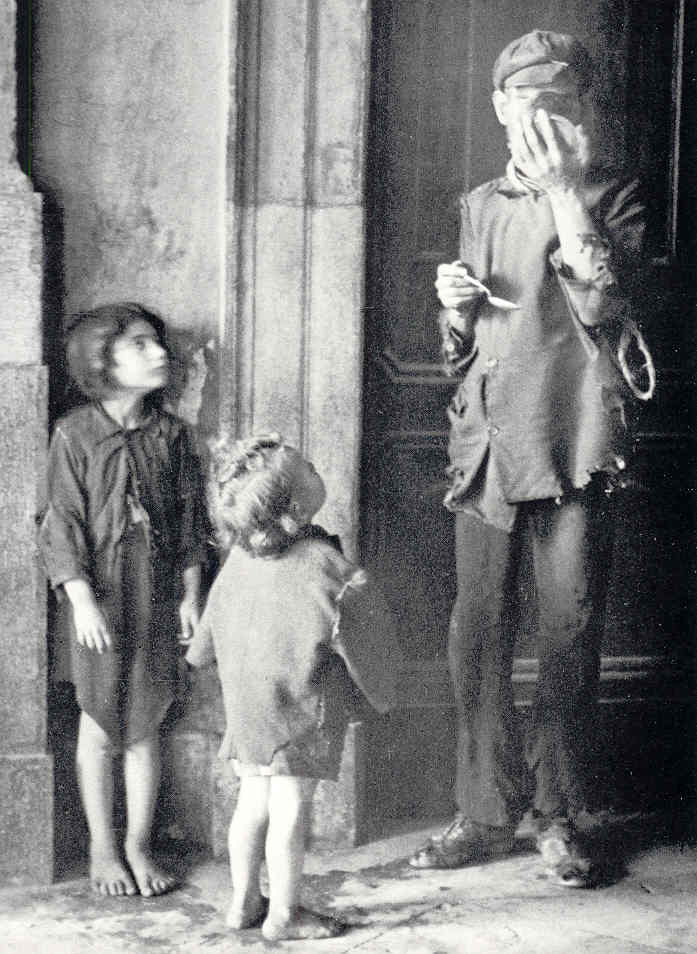

Hunger in Palermo,

Sicily

Homeless orphaned sisters

on a street in Rome

Toni Frissell – courtesy

of Frissell Collection, Library of Congress

But somehow life goes on

German farmers and miners

gathering with families and possessions

to move from the horribly

overcrowded American sector to the French sector

where skilled labor was

actually in short supply

National Archives

Some citizens of Cologne,

Germany, resuming as much a normal life as possible –

though for most life amounted

to a constant search for food, shelter and clothing – 1946

Sheep resuming a normal life

in a bombed out hangar in Leipzig

One quarter of the city was totally flattened

by Allied bombing

Britishers looking for coal – Feb. 1947

Cold, rundown mines and

lack of transport made the fuel shortage worse than during the War

Recovery was not quick: Hamburg still in Ruins – 1947

|

|

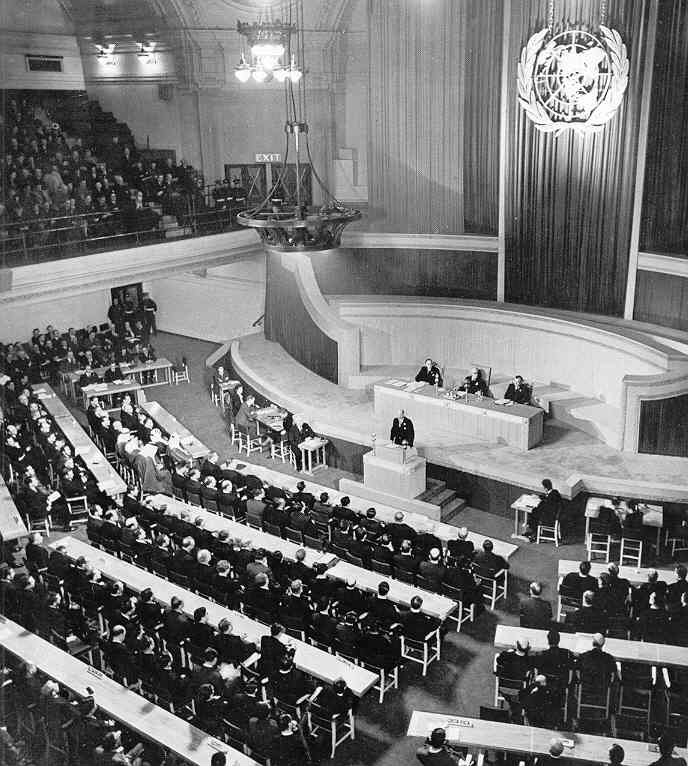

As far as the rest of enemy Europe was concerned (most all of it except Italy under occupation by the Russian Red Army), the design of the futures of Italy, Austria, Rumania (soon to be termed Romania), Bulgaria, Hungary and Finland was turned over to a special Council of the Foreign Ministers of the Big Five. When the Foreign Ministers finally gathered in Paris (July-October 1946) they found the going slow in their attempts to find agreement in the handling of these former enemy nations. Russia wanted the Italian colony of Libya (giving Russia finally a position on the Mediterranean), but America and Britain would not back down in their refusal. Russia also wanted a huge reparations payment ($300 million) from Italy. But that too was blocked by the Western allies. However the final treaties did provide for extensive land transfers and large reparation payments to the Allies (Russia, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Greece principally) and a huge reduction in the size of their former enemies' armed forces. Finland, which had been attacked by Russia – and consequently found Germany to be its only practical ally – now had to pay Russia $300 million for damages and surrender territory to the Russians. And in the end the Italians were required to pay Russia $100 million, Yugoslavia $125 million, Greece $105 million, and were forced to give up all their colonies. The city of Trieste, once the most important port city of Habsburg Austria's empire, and its rich hinterland (inhabited by both Italians and Slavs), found itself caught between Italy and Yugoslavia in its post-war assignment. It was finally decided to place Trieste under United Nations administration.1 1In 1954 the Trieste province would be

divided in half with the western portion, including the city of Trieste

itself, assigned to Italy and the eastern and southern portion assigned

to Yugoslavia (eventually to Slovenia and a smaller section to Croatia).

|

|

The General Assembly of the

United Nations meets in London – 1946

United Nations Headquarters – New York City

Eleanor Roosevelt – Truman's

representative at the United Nations

United Nations

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges