|

|

American "Anti-Imperialism" American "Anti-Imperialism" The Dutch struggle to keep their empire in Southeast Asia The Dutch struggle to keep their empire in Southeast Asia Under heavy pressure from Gandhi, India receives Swaraj (independence) Under heavy pressure from Gandhi, India receives Swaraj (independence) The Chinese Civil War (1947-1949) The Chinese Civil War (1947-1949) The Israeli-Palestinian Question The Israeli-Palestinian Question The French struggle to keep their empire in Indochina The French struggle to keep their empire in IndochinaThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 70-84. |

|

|

Meanwhile, at the other end of the world, the war had its own powerful effect on the way things took shape in Asia – as the Americans and Europeans attempted to piece back together what had been their former place in the scheme of things. But that was not exactly going to happen. For the Europeans at least, their long-held position of dominance in the world seemed to be coming to a close. American "anti-imperialism" At the same time, the new superpower America was well-pleased to be able to demonstrate its Democratic Idealism when on July 4th, 1946, it finally accorded full independence to its partially self-governing Philippine dependency or Commonwealth of the Philippines, a move it had actually planned before the war with the Japanese erupted. |

The US flag comes down in the Philippines – July 4, 1946

|

For America itself this was conceived as

a grand gesture of great moral significance, because America considered

itself to be by nature anti-imperialistic due to its own supposed

"birth"1 in 1776 through rebellion against English imperialism. Anti-imperialism even stood as the keynote of American foreign policy, at least since the presidency of Woodrow Wilson in the early 1900s. Disregarding their own march across the North American continent – in which they swept aside the natural resistance of the Indian tribes and Mexicans already established in the American West in order to plant their own Anglo society there – and likewise disregarding the military power used to force a slave-holding South to remain in the Union minus its slaves, Americans had somehow come to believe that American society had achieved its greatness through simply its own superior moral qualities, its basic "goodness." And thus America came to the conclusion that its mission in the world was to demonstrate its commitment to those same high moral qualities by insisting that its friends and allies take up the same "post-imperialist" character. In other words, the rest of the world – or at least those in the "Free World," as Americans were beginning to term their particular sphere of global influence – must demonstrate the same generosity by abandoning their imperial positions in the rest of the world, just as America did in the Philippines. As Americans saw things, its European

friends were now – having failed to follow Wilson's call to do so after

World War One – finally to pull back from their global positions

outside of their own homelands in Europe. The British, French, Dutch,

Portuguese, Belgians, etc. needed to go home, and leave to the

oppressed peoples of the world their own right of "self-determination"

(self-government). Almost immediately those countries experiencing American-encouraged (or even American-enforced) independence would fall into violent civil war – finally brought to a close through the takeover of a local dictator of the most brutal variety, or it would get dragged into the bitter Soviet-American competition for cultural dominance in these newly freed societies – new battle zones in the on-going Cold War waged between these two superpowers. Ironically, America would have great difficulty in understanding how its "pro-democracy/anti-imperialism" posturing would itself come across to others as highly imperialistic – not to mention highly disruptive of a people's cherished social order. And worse, America would simply refuse to take a close look at the lessons about its own power programs that it should have learned along the way, continuing to walk into the same disasters generations later, still attempting the same failed Humanist Idealism in Vietnam, Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, not to mention in multitudes of cases to the south of its own country in Guatemala, Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, Chile, etc. Americans refused to understand that democracy is a social responsibility taken up by a society of individuals well-trained to assume those responsibilities personally, lest those responsibilities be taken on by autocratic or dictatorial personalities, "enforcers" of a social order that the people themselves were not able to bring into being – or maintain in the face of energetic human ambition. Democracy is not "natural" to anyone. The disciplines and responsibilities of democracy are either carefully taught to rising generations by those most directly involved in the social-moral indoctrination of children (namely their parents), or else authentic democracy simply does not take place. It is not achieved by natural instinct as Humanists believe – believe religiously. Humanism itself is in fact a very frightful religion, because socially, economically and politically it so easily becomes irresponsible – and dangerous to human life. 1Many Americans consider the War of Independence of the 1770s and 1780s as the time of the nation's birth, not realizing that America had already experienced 150 years of very formative independent existence by that time. 2But moral self-congratulation has always been a blinding force in the lives of all-powerful people.

|

|

The Dutch economy was very

dependent upon the wealth coming from its southeast

Asian colony – and the Dutch were in no

mood to let go of this invaluable asset.

|

Unlike the Americans – releasing the Philippines to national independence – the Dutch at the war's end had no intentions of a similar sending off into independence of its extensive colonial holdings in Southeast Asia. The business back and forth between the Dutch home-base in the Netherlands and its overseas territories in Southeast Asia was considered to be absolutely essential to the Dutch economy. Also, three hundred years of connection had made a cultural impact both ways between the Dutch and the Southeast Asian islanders. Furthermore, during its long period there, the Dutch had succeeded in keeping a fairly tight control over political developments in the entire region. But in the days when the end was clearly in sight for the Japanese Empire, the Japanese authorities – who for three and a half years had held the Dutch colony under tight control and who had destroyed much of the Dutch economic and social infrastructure – worked hard to make the return of the Dutch to their colony as difficult as possible. They encouraged the Asians to rise up against the returning Dutch, supporting even in the days immediately after the war a proclamation of Indonesian independence by the local nationalist leader Sukarno and his close associate Mohammad Hatta. Also, many of the weapons that the Japanese were forced to lay down in surrender went purposely to arm the Indonesian nationalists. The Dutch therefore found the return to their colony resisted heavily by a new group of anti-Dutch nationalists. Indonesian resistance was chaotic, because of the vast cultural mix found on the islands (including even a large Chinese minority group). Ethnic massacres became frequent, with tens of thousands reported killed or missing in the first year of the resistance alone. Several thousand Europeans were known specifically to have been tortured and executed and as many as 20,000 of mixed European-Asian ancestry were killed or went missing (probably suffering a similar fate, though most likely their bodies were thrown into the sea; some mass graves were later uncovered). Also, some of the outer islands (which were Christian rather than Muslim as was much of the rest of the colony) were less than enthusiastic about the nationalist uprising. In early 1946 the Dutch were back in

business enough to send an army to Indonesia in an attempt to bring the

region back under Dutch rule.2b And by 1947 the Dutch seemed to be

succeeding in re-establishing Dutch authority over its colony,

especially in the more populous areas of Sumatra and Java. But the Dutch found that the Republicans were not really interested in respecting the cease-fire line, and given their growing diplomatic isolation the Dutch began to see their cause dying. Thus in late December of 1948 they made one last grand effort to put themselves back in power. They regained much of urban Indonesia, but could make no progress in the countryside. Furthermore, the members of the U.N. Security Council (including anti-imperialist America) were lining up strongly against the Dutch. America not only cut off all Marshall Plan aid originally designated for the rebuilding of Dutch Indonesia, but threatened to cut off all aid to the Netherlands itself. Americans were very unhappy at the thought that their grants in aid, which equaled about half the budget allocated to the effort to restore Dutch rule in Indonesia, could be indirectly supporting Dutch imperialism. With the world lining up against them, by the summer of 1949 the Dutch were ready to quit. Discussions opened up in August and by November the Dutch had come to an agreement in support of Indonesian independence, under the man who would become Indonesia’s dictator, until another military leader, Suharto, forced him to step down in 1967 – in one of the 20th century’s most brutal takeovers. Suharto would then rule Indonesia for the next thirty-one years. And thus it was with the Dutch gone, Indonesia stepped into "self-government." 2bSince the wars end in August of 1945 the region had been under a rather feeble British administration, British Indian and Commonwealth troops having been sent to the islands largely to receive the surrender of the Japanese, not to defend Dutch interests!

|

Sukarno (with Mohammed Hatta

on the right) announcing Indonesian independence

– August 17, 1945 – two days after the Japanese

surrendered to the Allies

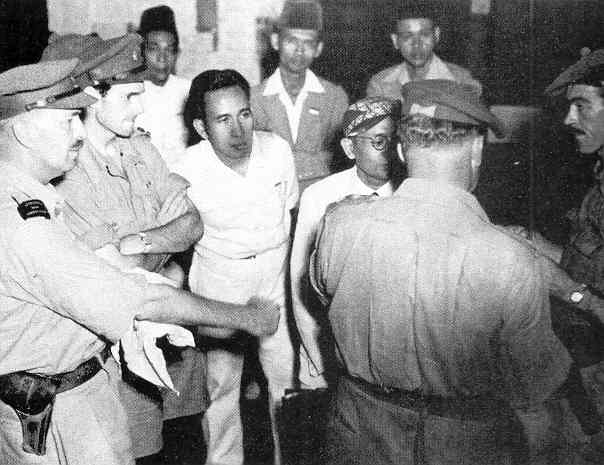

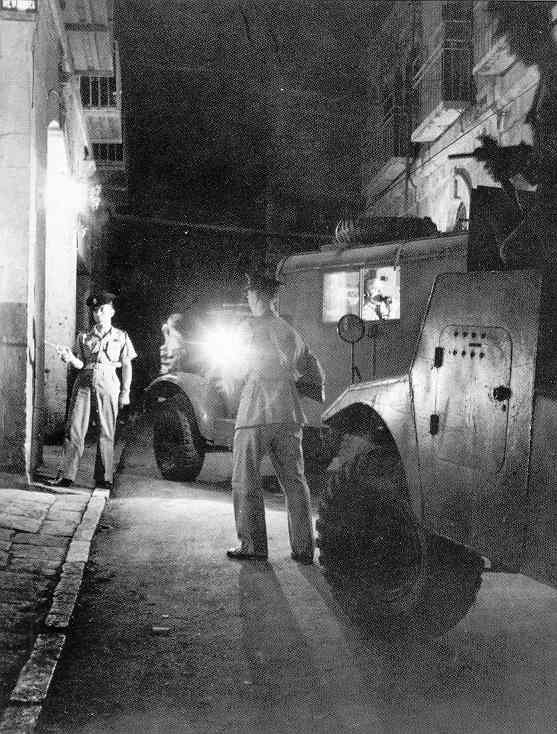

British soldiers, acting

on behalf of the Dutch,

questioning Indonesians about nationalist activities – 1945

| Not until September did the British arrive in Indonesia, to take over from a greatly demoralized Japanese occupational force – giving the Indonesian nationalists weeks of opportunity to establish themselves. |

British Indian troops encountering

the first major uprising of the Indonesian nationalists

November 1945

Imperial War Museum,

London

| When the Dutch finally were able to begin taking over from the British it was early 1946 – and they found themselves facing a well-developed nationalist movement among the Indonesians. |

Dutch soldiers and Indonesian

civilians at a checkpoint in Djakarta

Dutch Institute for Military

History

Skulls and bones of Dutch

civilians murdered during Indonesian Independence-Day celebrations

at Balapulang – August

17, 1946

Government Institute for

War Documentation, the Hague

UN military observers checking

up on a UN-sponsored cease-fire – 1948

National Archives

Indonesians remove from the

Djakarta palace portraits of their former Dutch governors – 1948

Aerial photo of Dutch parachutes

and cargo planes at Maguwo Airport near Yogyakarta after Dutch

paratroopers

and regular troops attacked the nationalist position there – December 19,

1948

Crowds in Djakarta celebrating

the 4th anniversary of Indonesian independence – August 17, 1949

National Archives

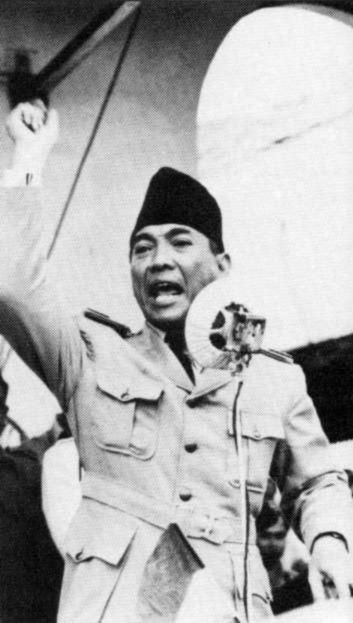

Achmed Sukarno challenging his Indonesian countrymen to grand acts of patriotism

|

|

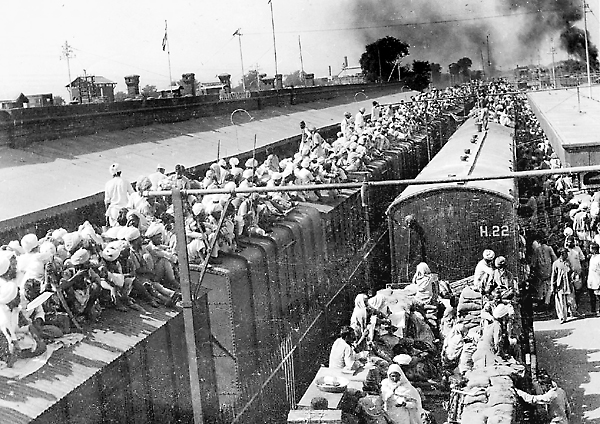

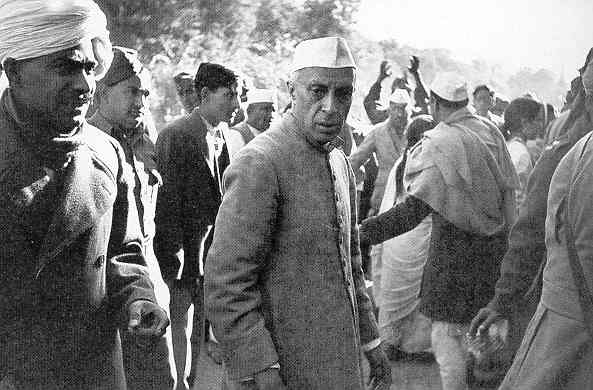

Unlike the Dutch, the British under Clement Atlee's post-war Labour Ministry were rather eager to divest themselves of their former responsibilities in Asia. The British Labour Party always had a strong distaste for empire, claiming that Britain's economic investments in India undercut jobs for the working class in Britain itself, not realizing that the Indian connection actually fed British industrialism – and thus jobs for British laborers. Also, Labour considered economic problems at home far more important than Great Britain's former responsibilities in the larger world (one of the reasons why Churchill came to America in 1946 to appeal to America to take up the responsibilities that used to belong to Great Britain). Even in his days as British Prime Minister, Churchill knew that India was going to have to be granted a greater degree of self-rule, although he was hoping that somehow India would still remain as a member of the British Empire that he loved so much. But Mohandas Gandhi always had other plans. He wanted the English to "Quit India" entirely. He not only wanted the English gone but also the culture they had brought with them to India. Gandhi had some kind of fond dream of India returning to some version of an ancient Indian grandeur – pre-industrial, pre-modern. Thus he had shed his Western lawyer's attire, had taken up the appearance of a Hindu holy man, and had set a proper Indian economic example by spinning his own yarn at his spinning wheel, to make his own clothing. His goal therefore in his quest of Indian independence was not to achieve modern industrialism on India's own national model, but to ditch modern industrialism altogether.3 On this matter however his view was not widely shared by his colleagues in the Indian nationalist movement, in particular Jawaharlal Nehru (the future prime minister of independent India) who was an ardent modernizer. Nonetheless, the other Indian nationalists humored Gandhi in his romantic vision of independent India. He was, after all, the Mahatma or Great Soul of India. They needed his charisma to give momentum to their independence movement. But British India was a complex of a number of ancient states, various languages, even different religious communities (Hindu, Islam, Sikh, Parsi), not to mention different castes that had rigid rules keeping them at a distance from each other. India was not really a nation, but instead a Europe-sized subcontinent of some 500+ states. The British had maintained authority in this complex India through an array of different treaties with the rajas (Indian rulers) of these states, British Indian government supplemented by a huge bureaucracy that directed the rest of the Indian subcontinent not covered by these treaties. How Gandhi was going to hold all this together following a British departure was something that remained a mystery to everyone. To the sizeable Muslim community in India, the vision projected by Gandhi was deeply disturbing, because it definitely had strong Hindu overtones. The Muslims, used to centuries of Muslim control over the subcontinent prior to the arrival of the British, had no desire to see the Hindus take up where the Muslims once left off. Indeed, the Muslim League, speaking on behalf of India's Muslim community, wanted no part of Gandhi's India. They thus petitioned the Atlee government to set up separate Muslim and Hindu states or dominions at independence, in particular an independent Pakistan4 to gather the Muslims. That was not going to be easy, and not just because Gandhi stood entirely opposed to the dividing up of his India. Muslim communities were most prevalent in the very western and the very eastern parts of India. But by and large there was a good mix of both Muslims and Hindus all through India. Also the definition of Muslim or Hindu states had traditionally depended on the religion of the raj rather than the people themselves within these different Indian states. If India were to be divided into separate Muslim and Hindu states, how would boundaries thus be defined? And what about Kashmir for instance? It would be very hard to decide where a Muslim-Hindu boundary line would be drawn through this northern province. Then there was also the question of the large Sikh community living in the west and northwest of India, who historically had a huge empire in southern Afghanistan and northern India, located principally at the headwaters of the Indus River, the Punjab (Five Waters). Their fate now however was most uncertain amidst this contention between the Hindus and Muslims. There really was no good answer as to what the Indian subcontinent was to look like with the British departure. But the British were quickly losing interest in the question. British Lord Mountbatten (a member of the British royal family and Viceroy of India) was given instructions by the British government to prepare India for independence, by no later than 1948. But seeing the dangers of communal schism mounting, Mountbatten pressed for an early date and got representatives of the Hindu, Muslim and Sikh communities to come to an agreement in June of 1947, calling for independence within the next couple of months. (Gandhi remained adamantly opposed to the agreement by which India was partitioned). On August 15th British rule ended in India. Seeing the division of India taking shape and (rightly) fearing massive genocide, millions5

of Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus took to the roads to get to areas where

their religion would dominate. Hundreds of thousands died in the brutal

chaos which accompanied these mass migrations.6 The worst off perhaps were the Sikhs, who ultimately got no particular region designated as devoted to their people. It was perhaps merciful that it was a Hindu and not a Muslim that gunned him down; had it been the latter, the Hindu-Muslim violence would have been far, far worse than it already was. In fact the assassination helped sober up some of the extremists, and bring the new Indian leadership together (they were finding themselves quite divided over policy issues as independence approached). It also resolved a question which hung over India at independence. In which direction was India to head: towards Gandhi's pre-industrial traditionalism or towards Nehru's modern industrialism? With the loss of Gandhi, India now moved in Nehru's direction (and under his leadership until his death in 1964). India was thus spared an ideological feud between Gandhi and Nehru that might have turned quite ugly. India did not long remain a Dominion within the British Commonwealth. In 1950 India drafted a new constitution ending its existence as a Dominion, recasting itself now as a Republic (nonetheless remaining within the British Commonwealth of Nations). 3Gandhi seemed blissfully unaware of the fact that his effort to move India back into some kind of pre-industrial utopia would have put India at such a low level of economic capacity that millions of Indians would most likely have starved to death. 4Part of the name came from istan meaning place or land; Pak has a dual source as both the Urdu word for pure (thus Land of the Pure) or simply the acronym for the northeast region of Punjab, Afghanistan and Kashmir, or cleverly, both. 5The United Nations estimated that 14 million people were displaced during this migration. 6The exact death count is hard to calculate. The numbers vary from a low of 200,000 to a high of 2 million.

|

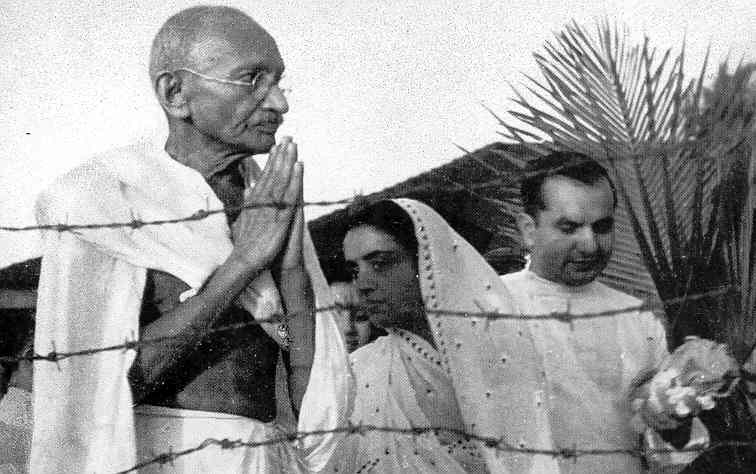

Gandhi after release from

prison in May 1944

| In early 1942, at a time when the Japanese were threatening to overrun the British Empire everywhere, Gandhi decided to resume his civil disobedience campaign to topple British authority in India. He refused to cooperate with the British in fending off the Japanese – and was arrested and detained for the next 21 months. |

Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru confer at a meeting of the Congress Party – 1946

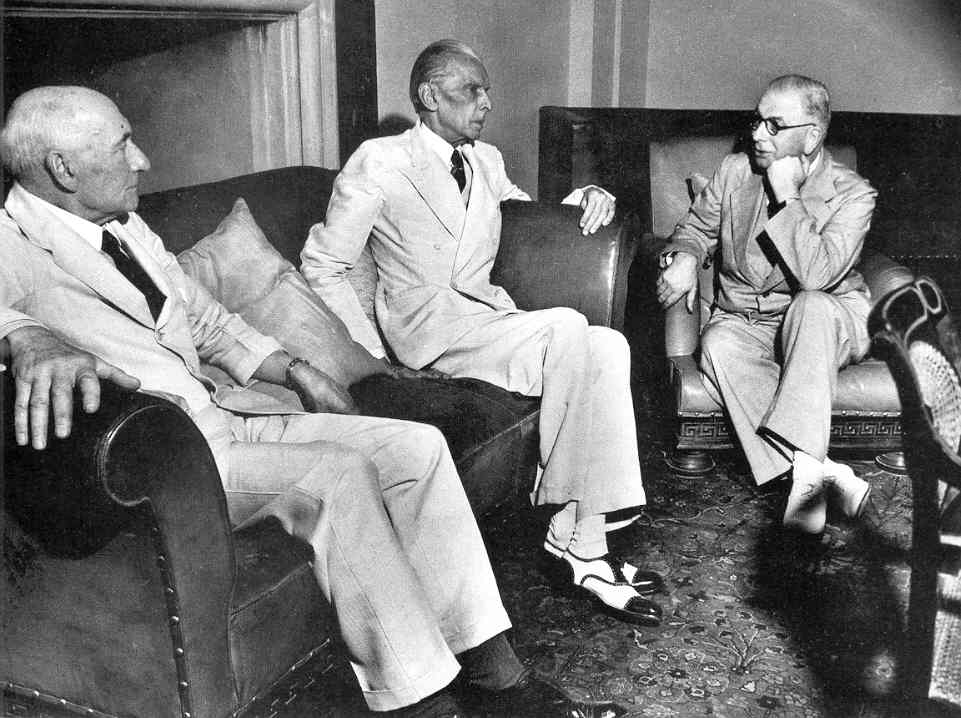

Muslim leader Muhammad Ali

Jinnah meets with British officials to plead the cause of

an independent

Pakistan, a separate Muslim state

carved out of British India –

something which Gandhi hotly opposed

Vultures and dead victims

of religious rioting – August 1946

The rioting occurred

when Ali Jinnah of

the Muslim League called on his people to

demonstrate against Hindu-dominated

Indian Congress Party of Gandhi and Nehru

Vultures preside over those

killed in Muslim-Hindu violence in the approach to Indian independence

Gandhi confers with Lord Louis Mountbatten in the days before Indian independence – 1947

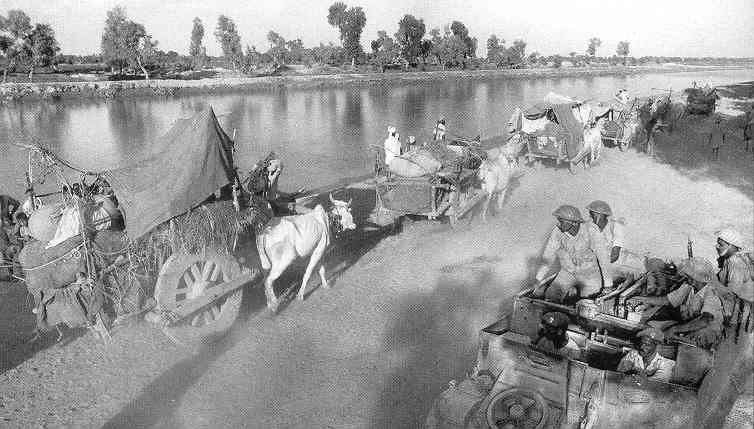

Muslim refugees passing a

shallow grave of victims of an attack by Sikhs

Refugees making their way from Pakistan to India under military protection – 1947

Gandhi on the 5th day of

his fast to compel the Indians to cease the Hindu-Muslim

violence

against each other – January 17, 1948

|

After

only five days, he presents himself as if he were at the edge of death

... hardly the case, but very dramatic ... and supposedly politically

very effective. Great political drama, Gandhi! He ended the fast the following day when leaders of both communities met to sign a peace agreement. 12 days later (January 30th) he was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic who was embittered by Gandhi's toleration of Muslims. Ironic justice for the London-trained lawyer Gandhi ... in his highly Romanticized effort to bring down India's well-developed social system (which was too "English" for him personally). |

Nehru and others in grief

over the news of Gandhi's assassination

Hindu women keeping vigil

beside the body of Gandhi

Mahandas "Mahatma" Gandhi

lies in state – 1948

The funeral procession carrying

Gandhi's body to the Jumna river where it is to be cremated ![]()

| By the spring of 1948

when the worst

of the cross migration of Muslims into Pakistan and Hindus into India had

finally slowed down (the Sikhs had no land of their own to migrate to)

as many as 15 million people had been transplanted in the two new countries.

The figures of those who died in this massive upheaval are unknown:

estimates run from several hundred thousand to as many as a million. And it left, deeply embittered, even millions more ... Muslims versus Hindus. |

|

|

Meanwhile things were getting very much out of hand in China. At the end of the war in 1945 the elected government led by America's wartime ally, Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek, was in a very shaky position. Chiang's public image in China had been badly tarnished during the war by the failures of his Nationalist (or Kuomintang) army to stop the Japanese from taking over the coastal cities of China (where his main support was originally concentrated) and by his having to rely on corrupt warlords and on foreigners (principally Americans) to maintain him in power in the Chinese rural interior to which he had to retreat during the war. Meanwhile the Communist guerrilla leader Mao Tse-tung (Mao Zedong) had built up a rapidly growing following: an army of Chinese peasants. But Mao and his army largely sat out the war. Mao had been virtually no help in getting the Japanese out of China, but was focused mostly on escaping the wrath of Chiang and his Nationalist army, which was heavily preoccupied with the Japanese. Mao's hit and run operations against extended Japanese positions gained him respect in the eyes of his fellow Chinese, but strategically did little to dislodge the Japanese army occupying the country. In sum, the Chinese took note of the fact that Mao had succeeded in not humiliating himself and his army with some embarrassing failure, whereas Chiang and his army (burdened with the greater war responsibility) appeared less than impressive as defenders of the dignity of China. In the eyes of the average Chinese this was a highly shameful situation for any Chinese ruler to find himself in. It registered with the Chinese much the same way the ancient idea of the Tianming (Mandate of Heaven) had once operated: such shame was the sure sign of the loss of that precious mandate deriving from the powers of Heaven (Tian). This would be a very difficult assessment for President Chiang to overcome, and all the American China experts were well aware of this fact. Economic factors also influenced the direction that China was to take after the war. Mao promised future land reform to the peasants, offering to seize the property rights of wealthy absentee landlords and hand land titles over to the peasants7 – making Mao very popular with the huge peasant population. Additionally, Chiang's inability to control inflation which skyrocketed after the war, destroying the savings of the urban middle class, undercut deeply the support of the one group that Chiang's Republic of China could usually count on. Mao clearly was gaining political strength at the same rate that Chiang was losing his. American diplomats (importantly Marshall) attempted at war's end to get the two Chinese factions to work together to rebuild China. But neither leader was willing to work with the other, their hatred for each other was so intense. Meanwhile, although openly Stalin supported Chiang's Republic of China, he was less openly supporting Mao's peasant army by seeing that weapons surrendered by the Japanese in Manchuria (which had been granted at Yalta to Russia to administer after the war) came into the hands of Mao's army, and also let Mao and his army move into controlling position in Manchuria as well. Truman countered by ordering the airlifting of thousands of Chiang's troops into eastern Manchuria (and sending U.S. troops there as well). But beyond that, there really was little America could do, as American power was spread thin with its occupation of Japan and its support of Western Europe. America could not resolve the problems of both Asia and Europe at the same time, and the situation in Europe appeared to be clearly more menacing to America than the situation in China. Again, Truman and his advisors8 tended to look at the situation in politically Realist terms of the specifics of national interest (great in Europe but less so in China) rather than political Idealist or ideological (general anti-Communism) terms. But that sophistication would not be easily understood by the American people, who more readily (often only) thought passionately in Idealistic or ideological terms. By mid-1946 the enmity between Mao and Chiang finally erupted into a full-scale war. Mao’s army tended to follow the program of passive resistance, slowly wearing down Chiang’s army in skirmishes fought in the countryside, at the same time that Mao’s army was expanding in size and territorial control. With each small victory of Mao over Chiang’s troops, better weapons (including tanks) fell into the hands of Mao’s rapidly growing Communist army. By 1948 the Communists were ready to take on Chiang’s positions in China's cities. Over the course of 1948 one city after another fell to Mao’s troops. In a two-month time period alone, between the beginning of December 1948 and the end of January 1949, numerous strategic cities in the north, including the all-important Beiping (Beijing), fell to Mao. Then in April of 1949 Mao’s troops were able to cross the Yangtze River to attack and capture the Republic's capital at Nanjing. Now Chiang’s troops were having to retreat south all the way to Canton. On October 1st, Mao announced the establishment of the People's Republic of China, with its new capital at Beiping. What was left of Chiang's army and political supporters – some two million of them – managed to escape the Chinese mainland and get themselves to the island of Taiwan. And with that, a new Chinese status quo set in. There would now be two Chinas, one with its capital at Beijing and one with its capital at Taipei on the island Taiwan. Which one would be entitled to the all-important China seat at the United Nations would become a point of major contention in the growing Cold War, as America would recognize only Chiang's government as the legitimate voice of China – and pressured its allies to do the same. The Soviets demanded that China's U.N. seat go to Mao's government in Beijing, and demonstrated their irritation at American intransigence by proceeding to boycott sessions of the U.N. Security Council, hoping to force other U.N. members to formally recognize Mao's regime as the true government of China. They would soon regret the decision to boycott those U.N. sessions. 7But then in 1958 Mao would take away that same ownership of the peasants’ lands when he forcibly "collectivized" China’s agricultural holdings with his "Great Leap Forward." 8Truman's

small society of foreign policy advisors was outstanding: besides

Marshall, Acheson, Lovett and Kennan, the list included Chip Bohlen,

Averell Harriman, Paul Nitze, John McCloy and many other highly

talented American statesmen. Most of these men served as advisors in

some capacity from the Roosevelt Administration all the way to the Johnson

Administration in the mid-1960s.

|

US C-54 plane transporting

Nationalist troops to Shanghai – October 1945

Bitter foes, Mao Tse-tung

and Chiang Kai-shek, putting on smiles at a reconciliation

conference

called by the United States

in August and September of 1945

Russian soldiers, who entered

the war against Japan a week before Japan's surrender, mixing with Chinese

in Manchuria, which they have just taken over from the Japanese – 1945

Fotokhronika-TASS,

Moscow

The British were quick to

retake the valuable Hong Kong colony after Japan's surrender in 1945

National Archives

Gen. George Marshall meeting

in Nanking in 1946 with Generalissimo and Madam Chiang Kai-shek

in the hopes of negotiating

a peace settlement between the Nationalists and Communists

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

and his wife with General George Marshall

U.S. Gen. George Marshall

brings together the Nationalists and Communists – March 1946

(Communist Chou En-lai,

Gen. Marshall, Communist Gen. Chu Teh,

Nationalist Gen. Chang Chih-chung

and Communist Mao Tse-tung)

Chinese warlord Ma Hung-kuei – powerful ally of Chiang's

Chiang Kai-shek being declared

President of China – 1947

Mao Tse-tung addressing his

followers as his move to oust Chiang

Kai-shek

gathers momentum – December 1948

Conscripts for the Nationalist's

last-ditch stand in Beijing against the Communists

December 1948

Chinese Communist troops

entering Beijing – February 1949

The Communists take over

Beijing – 1949

Dejected Nationalist soldiers

awaiting transportation out of Nanking

Nationalist Chinese fleeing

Nanking – 1949

Beneath a portrait of Sun-Yat-sen

the Nationalist parliaments ends its last session -

shortly before the Communists

take over Nanking – April 1949

Curious citizens of Nanking

getting their first look at Communist troops

Mao's Red

Army

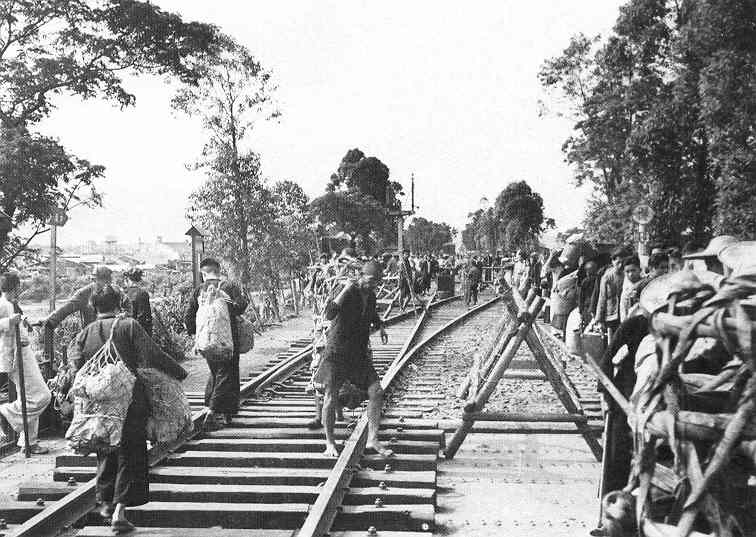

Chinese refugees (at right)

stream into Hong Kong from China in 1950

passing others going the

opposite direction

|

|

The ancient contest among Jews, Christians and Muslims At around the same time but at the other side of Asia, along the shores of the eastern Mediterranean, the British were facing another set of responsibilities, ones also that Atlee's British government seemed to have little desire to carry. The issue was Palestine – and who had the right/responsibility to govern it. The region had long been a place of major contention, being sacred land to three different religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It anciently was held by the Jews, until the Roman diaspora (scattering) of the Jews for their part in major uprisings against Rome in the 1st and 2nd centuries A.D. The city of Jerusalem had been not only the capital of the region but the political focal point of all who called themselves Jews, anciently as well as presently. But the area was also the homeland of Jesus (the Christ) and as the Christian Holy Land, something of a spiritual center of Christianity. And the Muslims also claimed the area, or more particularly Jerusalem, as the third most holy site in Islam The area became distinctly Christian with the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity in 313, but then was overrun by Arab Muslims in 637. Christian crusaders had briefly wrested it from the Muslims in 1099, but lost it again to the Muslims under Saladin in 1187. Eventually Muslim Ottoman Turks took over the region, governing it over the following centuries as the province of Southern Syria. The British assume governing responsibilities in Palestine The Turks lost big when they decided in 1914 to ally with the Germans in World War One. The British stoked the nationalist feelings of the Arabs against the Turks, encouraging Arab national resistance with the promise of turning captured Turkish lands over to the Arabs for their own governance. But in the famous Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British had also promised the same lands to the European Jews (a Jewish homeland), in exchange for much-needed Jewish financial support9 for the British war effort. And the British ultimately had interests of their own in the region. In any case the British ultimately

awarded the area to themselves in one of the follow-up treaties

officially ending the war. Palestine would become a mandate territory,

under British supervision … while supposedly the land would prepare

itself for eventual self-rule. Jewish Zionism

Palestinians, a mix of Muslim and Christian Arabs, began to be joined by European Jews who started to arrive in fair numbers after World War One as part of the Zionist Movement. Jews had always had major difficulties avoiding persecution by European Christians ... and the thought of setting up an independent Jewish nation where Jews would no longer suffer such persecution had a strong appeal among the Jews. This was especially true when the thinking turned in the direction of Palestine, the birthplace of Judaism. And so a large number of Jews began arriving in Palestine in the years after the First World War. This had upset greatly the Arab population living in Palestine. Jews had always been part of the cultural mix, possessing their own quarter in the capital city Jerusalem.10 But the mass arrival of Jews began to upset greatly the long-standing communal relations among the various religious groups. Particularly vexing was the problem of immigrant Jews buying from absentee Arab landowners (living off in the popular cities along the Mediterranean coast) farmlands in the Palestinian interior, which had whole communities of Christian and Muslim farmers living on them. Being thrown off the land to make way for Jewish kibbutzim (communal farms) stirred the Palestinians to such wrath that the British had been called on in 1936 to put down a major Arab revolt. This revolt dragged on brutally for several more years, with thousands of Arabs killed (and hundreds of Jews as well). One of the results of the revolt was the organizing of the Jewish immigration effort by David Ben-Gurion's Jewish Agency, and the development of a well-disciplined Jewish army, the Haganah, which would serve with the British in keeping order in Palestine (to the advantage of the Jews, of course). But relations between the British and Jews would be somewhat tenuous, as the British were also very sensitive about upsetting the larger Arab world, with which the British had strong political and economic interests in common. Consequently in 1939 the British published a White Paper announcing a limit on Jewish immigration into Palestine of 15,000 individuals per year. The Jews were upset. But the Arabs were still hardly delighted by even this number of Europeans coming in on their land. There really was no undeveloped land for the Jews to settle on. The Jews would thus have to displace Palestinians in order to occupy the land. Now the British found themselves up

against Jewish efforts to enter Palestine illegally in massive numbers,

as Hitler tightened the noose around the Jewish population in Germany

(and soon in the rest of German-occupied Europe). The British navy

attempted to hold off shiploads of Jews trying to enter Palestine,

sinking many of the boats in the process. The Jewish scramble for Palestine after World War Two

But this problem, as big as it was, was nothing by comparison to what exploded at the end of World War Two in 1945. The Allies were shocked by the sight of the multitudes of concentration camps scattered across central and eastern Europe, the dead and the walking dead they encountered. A good half of the inmates were Jews, sickly survivors of Hitler's efforts to exterminate the entire Jewish population of Europe. To make a very bad situation even worse, it quickly became apparent that non-Jewish people across central and eastern Europe, people who themselves had suffered greatly from the Germans, had little interest in seeing the Jews return to their homes. And with the shortage of jobs, housing, even food – and the growing ranks of DPs (Displaced Persons) – Zionism became very appealing to the Jewish survivors in Europe. As the inmates of the concentration camps were judged sufficiently recovered to leave the camps, thousands of them would find boat passage to bring themselves to Palestine. But the British were still trying to control the flow of European Jews into Arab Palestine. As a result, Jewish organizations began to take on the British Palestinian Authority. The Haganah took up the fight against British troops and installations, and Lehi (also known as the Stern Gang) and Irgun, led by Menachem Begin, took up the function of terrorists, brutally murdering British authorities and Arab civilian leaders (the Muslim and Christian Arab Palestinians had no military organization or officers of their own) in order to drive Arabs off the land and the British out of the country.11 Fed up with the thankless role of trying to mediate between the Jews and the Palestinians, the British Labour Party at this point (February 1947) announced that it was turning the matter over to the United Nations to resolve, and that July voted to terminate its Palestinian Mandate – effective no later than August 1948 (and earlier if possible). A U.N.-proposed Jewish-Palestinian division of the region The United Nations established a committee to come up with a plan to partition Palestine geographically, ultimately proposing a Jewish state – mostly along the heavily urbanized and more fertile Mediterranean coast – and an Arab state – in the southern Gaza desert region and the quite arid mountainous interior. It also proposed that Jerusalem city, located within the territory of the Arab state, would be internationalized under U.N. authority. The proposal, backed by both America and the Soviets, was satisfactory to the Jews. The Arabs, both in Palestine and in the surrounding Arab lands, however were totally opposed to handing over any Arab land to a new Jewish state. Further, they claimed that the United Nations had no authority to decide for the Palestinians their own future, as that right belonged only to the Palestinians themselves. Some of the committee members (India, Iran, Yugoslavia) proposed an alternate single federal state, and Australia ultimately abstained in the decision. In late November 1947 the United Nations General Assembly approved the plan (thirty-three to thirteen with ten abstentions). Britain let it be known that while it accepted the plan, Britain would not be the one responsible for instituting or enforcing it. In any case Britain at this point issued 14 May 1948 as its departure date. Meanwhile the surrounding Arab states announced their full opposition to the plan, even by military action if need be. And Begin's Irgun organization announced that it would not accept partition because the entire area, including Jerusalem, belonged to the Jewish nation alone. The dark clouds of war thus gathered. The contest for the control of Palestine becomes brutal Indeed, fighting broke out immediately with the announcement of the U.N. partition plan. Arabs tended to attack Jews in the cities, and Irgun, Lehi and the Haganah (especially Irgun) attacked Arab villages in the countryside. But Irgun was also busy in the cities bombing civilians' neighborhoods at will, to terrorize the Arabs into submission or flight. The most infamous was the Deir Yassin massacre by Irgun and Lehi, in which they moved house to house killing as they went, leveling the houses also. Rumors were also that they even shot Arab prisoners, women and children as well as men. True or not, these rumors helped enormously to put the Palestinian population into panicked flight. Soon floods of Arab refugees were abandoning their homes, shops and farms in an attempt to reach neighboring Arab nations, especially the new state of Transjordan, just east across the Jordan River. Also the city of Jaffa (which had been designated as belonging to the new Arab state) was attacked by Irgun and the Haganah with such intensity that its Arab population of 70,000 was reduced to a mere 4,000 when the fighting ceased. The formal withdrawal of the British in May of 1948 and the announcement by Israel's leader Ben-Gurion of the existence of the new state of Israel did not change matters much,12 for the fighting never let up. The partition plan of the U.N. was greatly ignored by the new Israel, which sent the Haganah into internationalized Jerusalem to lay claim to as much of the city as possible, plus ordered it to extend land boundaries as deep as possible into land designated for the Arab state. Furthermore, the Haganah was instructed to move as much of the Arab population out of the new Jewish zone as possible. Surrounding Arab nations answered the Israeli challenge with small military contributions, none of them coordinated in action nor large enough to do any real damage to the Israeli Defense Force (the former Haganah). Only in Jerusalem, where retired British officers commanded Jordanian Arab troops, was there effective resistance to Israeli expansion, enough that the Israelis were able to hold only the Western half of the city. Like Berlin, Jerusalem too would be a divided city, for a long time. Ultimately some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs who had fled their homes and who were not able to reach or settle in neighboring Arab countries were forced to settle in U.N.-run refugee camps, as the Israelis would not let them return to their homes. And here they stayed in tents, fed by U.N. food trucks, living on barren and unproductive land, far from any possibilities of employment, and destined to settle there indefinitely. A U.N. resolution called on Israel to allow the Arab Muslim-Christian refugees to return to their homes. But that went completely ignored by the new Jewish state. Thus a problem had taken root that would simply never seem to go away, one that would produce more than one future war and more diplomatic confusion than any other issue because the issue has always been insolvable ... despite repeated – but always failed – attempts by one American President after another to intervene to get both sides to see "reason." 9That support was expected from Europe's extremely wealthy Jewish Rothschild banking family, to whom the Balfour Declaration was in fact directed. 10The Muslims also had a quarter, and Christians possessed the two remaining quarters in Jerusalem. 11It is interesting to note that the Irgun leader Menachem Begin, who ordered the destruction of the King David Hotel (and 91 lives, including even Jews as well as British and Arabs) would become Israeli Prime Minister in 1977... and ironically become winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979. Also a former Lehi leader Yitzhak Shamir would follow Begin as Israeli Prime Minister in 1983, a man who ordered the assassination in 1944 of the British Minister for Middle East Affairs, Lord Moyne, and in 1948 the United Nations peace negotiator, Swedish Count Bernadotte. 12However, both America and Soviet Russia were quick to recognize the new Israeli government.

|

Anne Frank (2nd from the

left) and playmates – 1937

She would die at age

15 in Bergen-Belsen

camp; three of her playmates would survive

the Holocaust; her diary kept during her family's hiding

in Amsterdam (1942-1944) would

be found, published, and widely read after the war

Jews mourning relatives killed

in anti-Semitic violence in Kielce, Poland – 1946

The leaders were tried and convicted; but this nonetheless persuaded

thousands of Jews to emigrate.

A party of rather young and

very determined Jews sailing to British-held Palestine

to start a new life

there – 1946

| 3 million Jews survived the War – out of the original 10 million of Europe's original population. To many – if not most – Jews, an independent Jewish state in Palestine seemed to be the only guarantee that this would never happen again to their people. |

A Jewish husband and wife

- separated by the Nazis since 1941 – reunited in Haifa – May 1946

A British soldier at the

Haifa docks guarding Jews barred from entering Palestine![]()

| Fearing a massive rebellion from the Arab Palestinians who were irate at the post-War flood of immigrants into their land, the British began to seriously enforce an immigration restriction: only 1500 Jews per month. The huge additional flow of Jews that arrived were at first sent to Cyprus to await their place in the quota – a process that promised to be years in the making. Soon overwhelmed in Cyprus, the British took to returning the Jews to Europe. |

A ragtag Szold being

blocked by British troops from disembarking its passengers into Palestine

A Haganah soldier with Auschwitz tattoo doing sentry duty in Jaffa

| The 60,000-man army-like Haganah, led by officers who had fought alongside the British towards the end of the War, now turned its wrath upon its former ally. The Haganah blew up British radar stations, sank British boats patroling the Palestinian coastline, blew up oil refineries, British troop trains, RAF airfields and bridges, cut phone lines and oil pipeline and succeeded in isolating Palestine – and the British authority within it. |

A wing of the King David

Hotel being blown up by the Irgun terrorist organization

July

22, 1946.

91 Britons, Arabs and Jews died in the

explosion

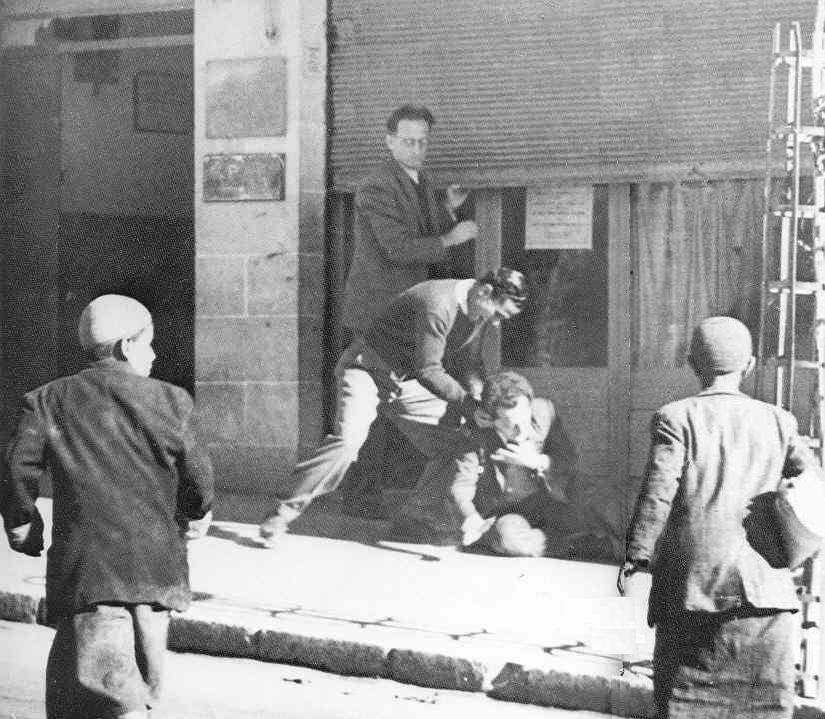

| While the Haganah attempted to focus on military targets and minimize human casualties, the 2000-man Irgun led by the Polish refugee Menachem Begin and the much smaller Lehi or "Stern Gang" worked in quite the opposite fashion. They gunned down their opponents on the streets, sent letter bombs, dressed themselves as Arabs or British soldiers in robbing banks, bombing train stations, attacking police stations and government offices, etc. By the end of 1946 they had also assassinated 373 people as part of their strategy of terror. |

British police about to invade

a suspected terrorist hideout in Jerusalem – October 1946

An Orthodox Jew being searched

before being admitted into a British compound for questioning

about the bombing of a British

officers' club by terrorists on a day (March 1, 1947) in which

16 attacks were

carried out against British targets, resulting in the deaths of 22 people

A Palestinian policeman guards

workers clearing wreckage of a train wreck – April 1947

The Cairo to Haifa

express train

carrying British troops was sabotaged by

the Jewish underground, killing

five soldiers and 3 civilians.

Two British soldiers executed

by the Jewish terrorist organization Irgun –

after the British executed

two Jewish terrorists – July 1947![]()

| A copy of the Irgun's execution orders is pinned to one of the soldiers. When the first body was cut down it exploded, wounding a British officer. The Irgun had mined the surrounding ground. On hearing of this atrocity, off-duty British troops in Tel Aviv rioted, killing 5 Jews and wounding 15 more. |

A Haganah refugee

ship Exodus-1947 impounded by the British at Haifa – July

1947

| To discourage further immigration of Jews, the British decided to make an example of this ship, ramming and crippling it just outside Haifa, and then transporting its 4500 passengers back to Europe in three prison ships. |

Defiant young Jews of the

Exodus-1947

being held in the Poppendorf D.P. [Displaced Persons] camp in

Germany

| The British guards at Poppendorf were less than enthusiastic about this assignment and the Jews were able simply to slip away. Within a year the camp was empty and the former detainees finally reached Palestine. |

Violence breaks

out upon the UN decision of November 30, 1947 that Britain's mandate

in

Palestine will end the following May and that Palestine will

be divided into two states,

with the coastal areas going

to the Jews

and the interior and the desert region of Gaza to the Arabs.

The Jews are elated; the

Arabs are furious. What gives the United Nations the right to give

Arab land away

to European Jews? It was the Europeans, not the Arabs, that mistreated

the Jews.

Now the Europeans are making the Arabs pay for the European

atrocities.

A Jewish journalist stabbed

by an Arab during the riots in Jerusalem that followed

the November 30, 1947 announcement

of the UN-sponsored partition of Palestine

A Jewish-owned taxi burns

outside the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem in retaliation for a drive-by

shooting conducted by Jewish terrorists which killed 15 people in the Arab

market.

During the month after

the announcement

of the pending partition, 489 people died in the violence.

Jews fleeing a bombing of

Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem – February 22, 1948

Jews surveying some of the

damage caused by the Ben Yehuda bombing

The bombing

was undertaken

by Arab terrorists dressed up in British uniforms.

57 people died. Angry

Jews, taken in by the deception, killed 9 Britons in retaliation.

On May 14th, 1948 Britain's

mandate over Palestine ended.

That afternoon the Jews

announced the creation of Israel.

On the following day the Arab-Israeli

war began.

Official UN mediator, Count

Folke Bernadotte,

assassinated by Jewish terrorist

organization Lehi (the Stern Gang) in September 1948

U.S. diplomat Ralph Bunche,

who replaced Bernadotte, mediating the Palestinian conflict

United Nations

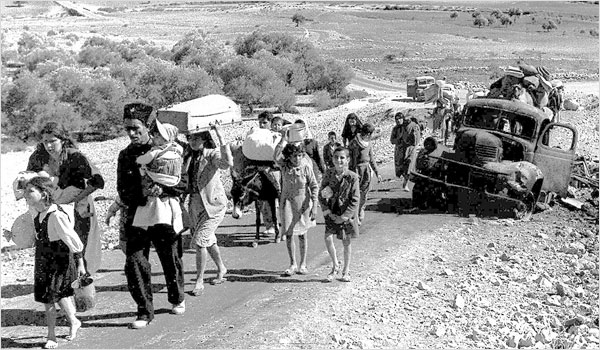

Palestinian refugees "Making

their way from Galilee in October-November 1948".

Front cover of The Birth

of the Palestinian Refugee Problem by Benny Morris

Israelis raise their national flag at the United Nations

Jaramana Refugee Camp for

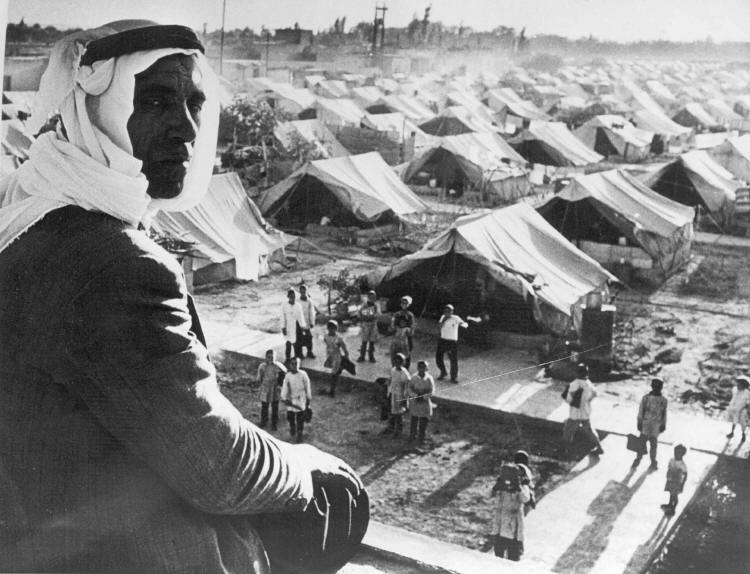

Palestinian refugees, Damascus, Syria – 1948

Palestinian refugees in Zerka refugee camp – 1949

Refugee routes of

Palestinians

Wikipedia – "Palestinian

refugee"

|

|

Unlike the British, and quite like the Dutch, the

French coming out of World War Two had no intentions of giving up their

colonial holdings in Asia. But the effort to reestablish their position

there would encounter major difficulties. The Vichy French government

had been something of an ally to the Japanese during the war and had

stood aside to let the Japanese occupy their colonies in Indochina (the

three Vietnamese coastal regions of Tonkin in the north, Annam in the

center, and Cochinchina in the south, plus Laos and Cambodia). With the

end of the war and with both the Japanese and Vichy French routed, the

new French Republic was eager to regain its French holdings in

Indochina. In September of 1945 Ho Chi Minh announced the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, but was blocked by British and French troops arriving to receive the Japanese surrender ... and to restore French control over the colony. But here too, the defeated Japanese meanwhile had been turning many of their weapons over to the Viet Minh. Consequently, fighting immediately broke out between the newly armed Viet Minh and the French and France's Vietnamese ally, the young Emperor Bao Dai – whose reputation among the Vietnamese was tarnished however because he had served as something of a Japanese puppet during the war. For the next few years fighting between the two sides remained mostly concentrated in Tonkin in the Vietnamese North and small in scale – except for one incident in 1946 in which heavy fighting broke out in Haiphong, the French bombarding the port city and killing 6,000 civilians, and driving the Viet Minh into the countryside. However, French troops, subsequently sent out to finish off the Viet Minh, found them hard to trap – and a cat and mouse game developed between the two sides. In 1949 the French created a State of Vietnam under the Emperor Bao Dai, an Associated State within the French Union, and under French supervision. And a Vietnamese National Army was set up by the French to patrol the less troubled regions. Also Laos and Cambodia were announced as similar Associated States within the French Union. But with the victory of Mao's Communists in 1949 in the Chinese Civil War, the situation in Indochina took on a new quality. Communist China began to send military assistance to the Viet Minh. And America finally began doing the same with the French. The matter had now become part of the larger Cold War.

|

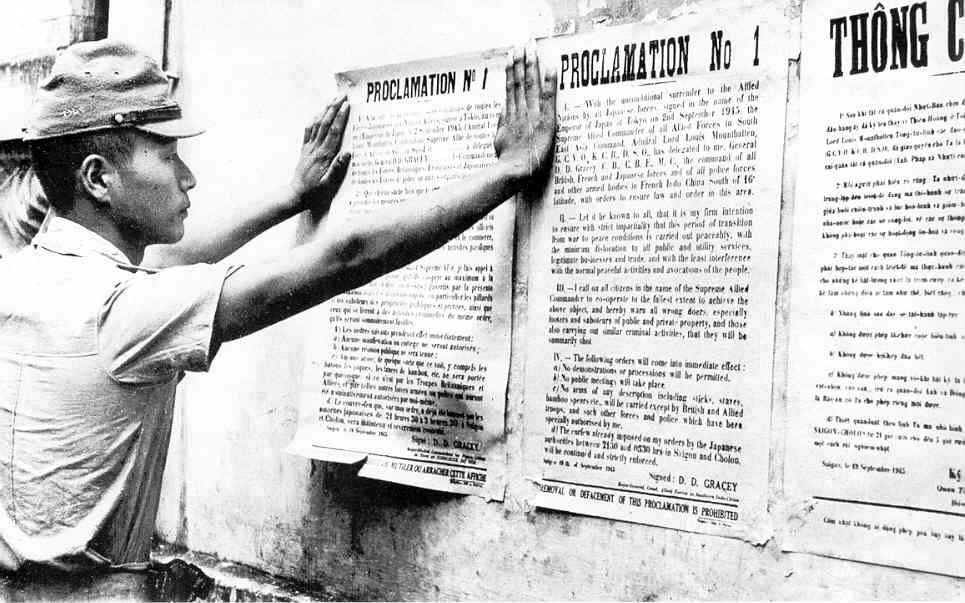

A Japanese soldier posts

Proclamation No. 1 declaring martial lawin English, French and Vietnamese

September 1945

Imperial War Museum,

London

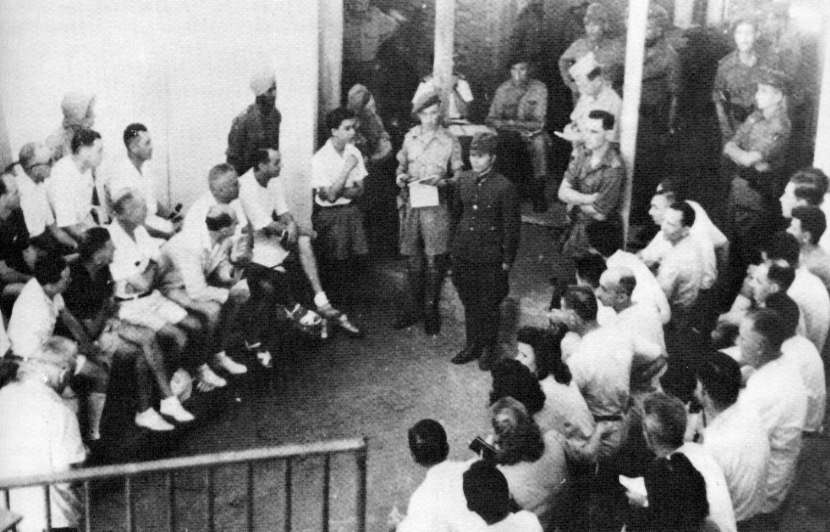

Japanese commander of a military

police unit in Saigon submitting his sword

to a Indian officer in the

British army – November 1945

U.S. Army

| The British were the first to enter the Japanese-held former French and Dutch colonies. The British kept the Japanese military in place for several months to help keep order until their European allies could retake their former colonies. |

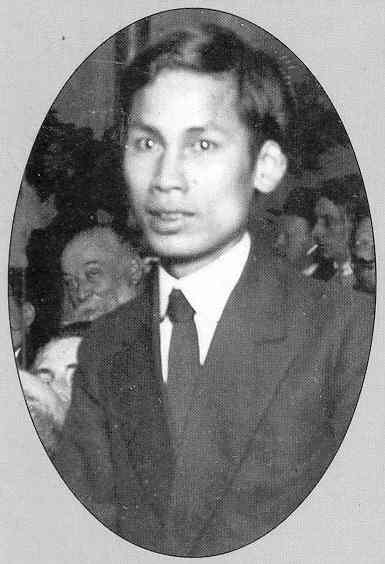

Nguyen That Thanh or "Ho

Chi Minh" ("He who enlightens") addressing the 1920 meeting

which gave rise to the French

Communist Party, of which he was a founding member

Ho Chi Minh (center) and

Vo Nguyen Giap (far left) with American OSS agents

planning coordinated action

against the Japanese – 1945

Ho Chi Minh proclaiming Vietnamese

independence – 1945

Under British command, former

French prisoners confront their former Japanese captors

Vietnamese nationalists in

Saigon taken prisoner by the French – September 1945

French troops leaving Marseilles

France for Indochina to retake control of the French colony

November

1945

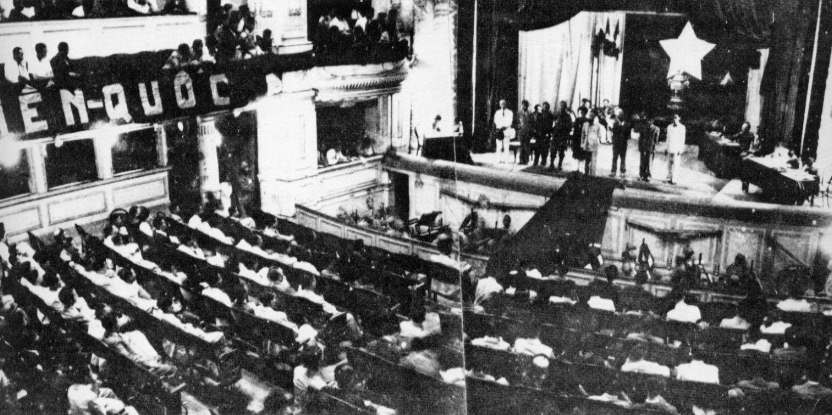

The first National Assembly

of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam meeting in January 1946

French Commissioner of Tonkin,

Jean Sainteny; Vo Nguyen Giap, Ho Chi Minh's Minister

of the Interior; and General

Jacques Philippe Leclerc, commander of the French forces in

the Far East, lead a contingent

to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Hanoi, March 1946

Ho Chi Minh arriving in Paris

to discuss Vietnamese independence

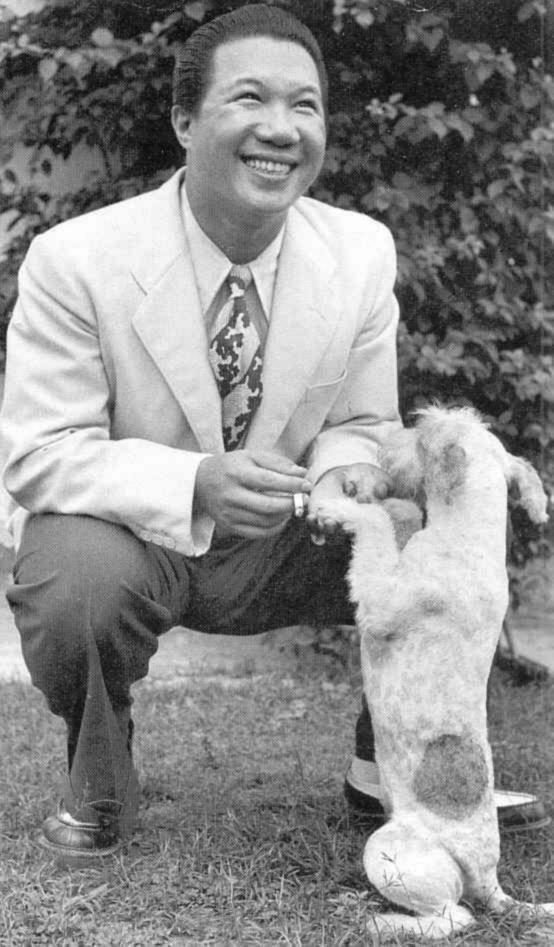

The Vietnamese Emperor Bao

Dai in exile in Hong Kong – 1948

He was returned to Saigon

in 1949 in a French effort

to form a new non-Communist

government

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges