The Suez Canal had been built by French engineers

back in the 1860s, with ownership shared by private French investors

and by the Egyptian king. But in 1875, because of a major financial

crisis in Egypt, the king sold all his shares to the British

government, which was very interested in the canal because it provided

a direct link between Great Britain and the British Empire in India.

Indeed, it was so important to the British that they eventually placed

themselves in the position as protector of the Egyptian government, and

would continue in that role in the decades ahead – even into the

beginning of the 1950s.

But economic hard times in Egypt at the

beginning of the 1950s had produced widespread protesting in Egypt,

leading to the dismissing of the king and his replacement by a military

council, one that would eventually be led by the very ambitious Gamal

Abdel Nasser – who took for himself not only the role of president of

Egypt but potentially the leader of the entire Arab world. After all,

the divisions of that Arab world into the (fictional) nations of Iraq,

Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, etc. had been designed

by the European powers – and not the Arabs themselves – during a period

of robust Western Imperialism, mostly just before or immediately after

World War One, solely according to European power considerations.

Nasser however intended to unite that

broader Arab world into a single United Arab Republic, under his own

leadership of course. But he had a contender for this leadership

position in the form of the Prime Minister of Iraq, Nuri al-Said – who

himself had the same ambitions as Nasser, and who also enjoyed a close

working relationship with the British.

The British, now back under Conservative

Party leadership, were again attempting to maintain something of a

pivotal position in the Middle East. Thus they had set up the Baghdad

Pact in 1955, uniting al-Said's Iraq with Pakistan, Turkey, and

Britain. Nasser was invited to join, but suspected that to do so was to

undermine his own position in the Arab world to the benefit of Nuri. He

thus refused to join, and drew Egypt away from the former close

relationship it had long held with Britain. In fact at this point,

Nasser began to portray Britain as the Arab world's major stumbling

block in its quest for collective unity and Arab national pride. It

would thus not be long before British Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden

would develop a passionate hostility towards Nasser.

At the same time, the French were growing

increasingly hostile toward Nasser for his support of the Arab

rebellion going on within Algeria (which at the time was considered an

integral part of France itself). And Israel was just as angry toward

Nasser for his support of Palestinian fedayeen and their attacks on

Israeli settlements, and for his refusal to allow Israeli ships – or

any ships supplying goods to Israel – to pass through the Suez Canal.

Consequently, by early 1956, both France and Israel found themselves

working closely together in their desire to neutralize Nasser. The

British would soon join them in this enterprise.

Meanwhile, Eisenhower's America was

focused intensely on the ongoing Cold War with Soviet Russia, deeply

concerned that the Soviets were going to make a move to insert

themselves in the heart of the Middle East. For Eisenhower's Secretary

of State Dulles, this concern to keep the Soviets contained also was

passionate, almost obsessive.

The Americans wanted to build a NATO-like

military defense organization focused on the Middle East, and like the

British had tried to entice Nasser to join, recognizing him to be of

central importance to any plan to unite the Arab world against Soviet

expansion. But when Nasser could not secure military arms purchases

from America (because of an earlier agreement among America, Britain,

and France to minimize Arab-Israeli tensions by cutting back on arms

sales to the Middle East), in September of 1955 he purchased Soviet

arms through Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia, irritating Dulles and

Eisenhower greatly.

Soon after this, trouble also erupted

between America and Egypt over the financing of the construction of the

very expensive Aswan High Dam along the upper Nile River. This project

was deeply important to Nasser as a means of providing Egypt with both

hydroelectric power and flood control protecting farms and industries

along the Lower Nile. America had been supplying funds for this venture

with the expectation of drawing Nasser into the American political

orbit. But when in May of 1956 Nasser extended official recognition to

Mao's Communist China, this angered Eisenhower so much that he cut off

funding for the project. Eisenhower expected that Nasser would then

turn to the Soviets for financial assistance, but find in doing so that

the Soviets would not be able to grant funding equal to the loss of the

previous American support. This then should drive Nasser back into the

arms of the Americans

But instead Nasser decided in late July

of 1956 to grab the one money-maker he had at hand, the Suez Canal,

still owned by British and other foreign financial interests. This

immediately spun the diplomatic world into a round of debate as to how

to respond to Nasser's actions – in violation of a number of

international laws, but more importantly with a number of political

implications for Britain, France, Israel, and even Iraq. For instance,

Iraqi King Faisal and Prime Minister Nuri urged immediate military

action. But the British Parliament was divided between those also

wanting such action, and those who insisted that Nasser's actions did

not warrant military attack. Also the English dominions Canada,

Australia and New Zealand were very lukewarm on the idea of a military

response to Nasser. To Australia and New Zealand, the Panama Canal was

much more important to their national interests than the Suez Canal.

The French on the other hand were a bit more united (except the French

Communists) around the idea of a military countermove, for Nasser

needed to be curbed, not just for his actions concerning the canal but

for his support of the Algerian Arab nationalists who were trying to

split the Algerian Department from the rest of France (which had

millions of non-Arab Frenchmen living there, plus many Algerian Arabs

who also saw themselves as French first and foremost).

Eisenhower urged his European allies

merely to proceed cautiously in their response to the crisis, something

that upset French Prime Minister Guy Mollet, who expected stronger

support from America – especially since, out of loyalty to NATO, he had

passed up an offer from the Soviets to cease their support of the

Algerian Arab nationalists if the French were to drop out of NATO. This

weak response of Eisenhower seemed to indicate to the French that they

were going to have to respond to Nasser on their own, with or without

American support.

For the next couple of months America

held the upper hand in trying to get its allies and Nasser to come to

some kind of diplomatic solution to the crisis. Eisenhower was hoping

to mobilize the broader world opinion against Nasser as a way of

forcing him to return control of the canal to its European owners.

Eisenhower even proposed some kind of international authority

controlling this strategic canal. Meanwhile the British and the French

quietly went along with all the diplomatic maneuvering, mostly to give

themselves the time necessary to prepare themselves for a military move

on the canal (they were actually working together in their military

planning, including also Israel).

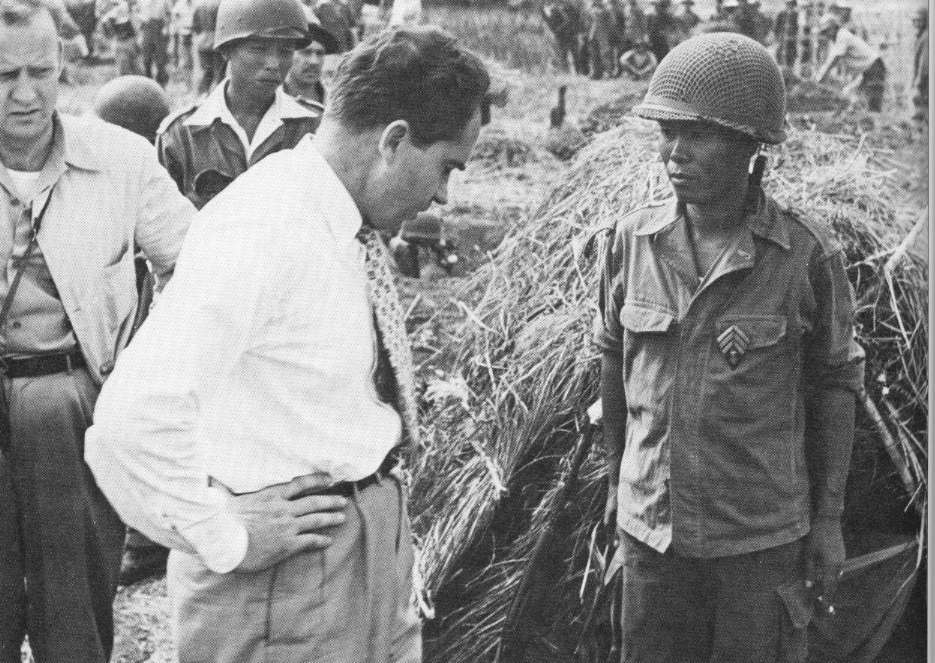

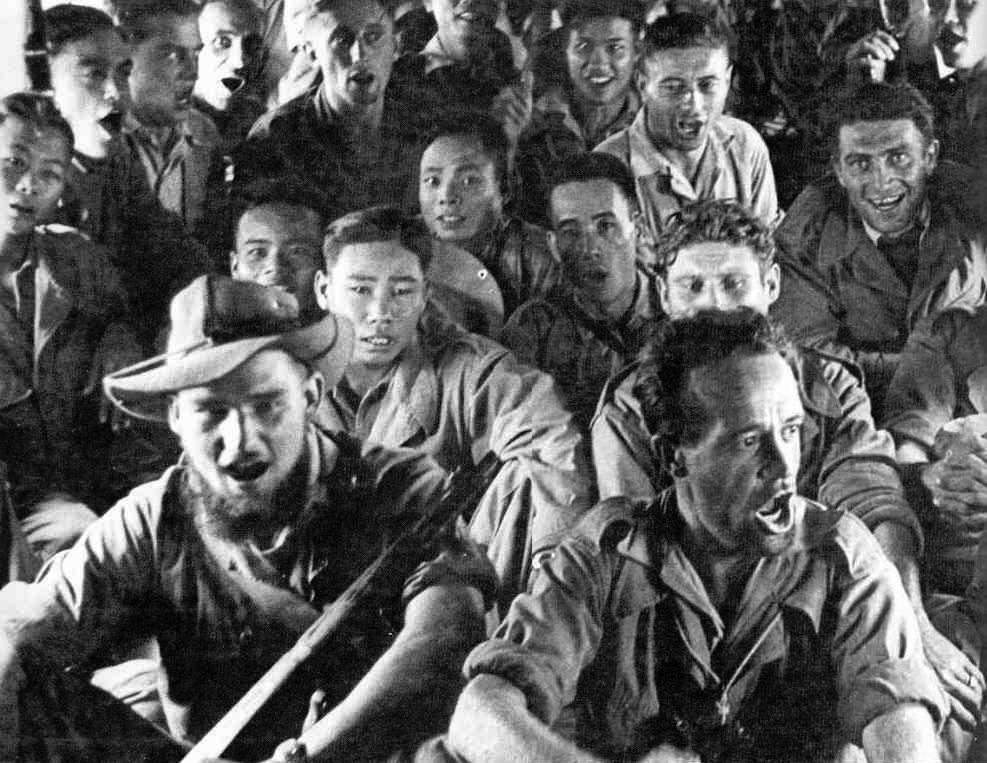

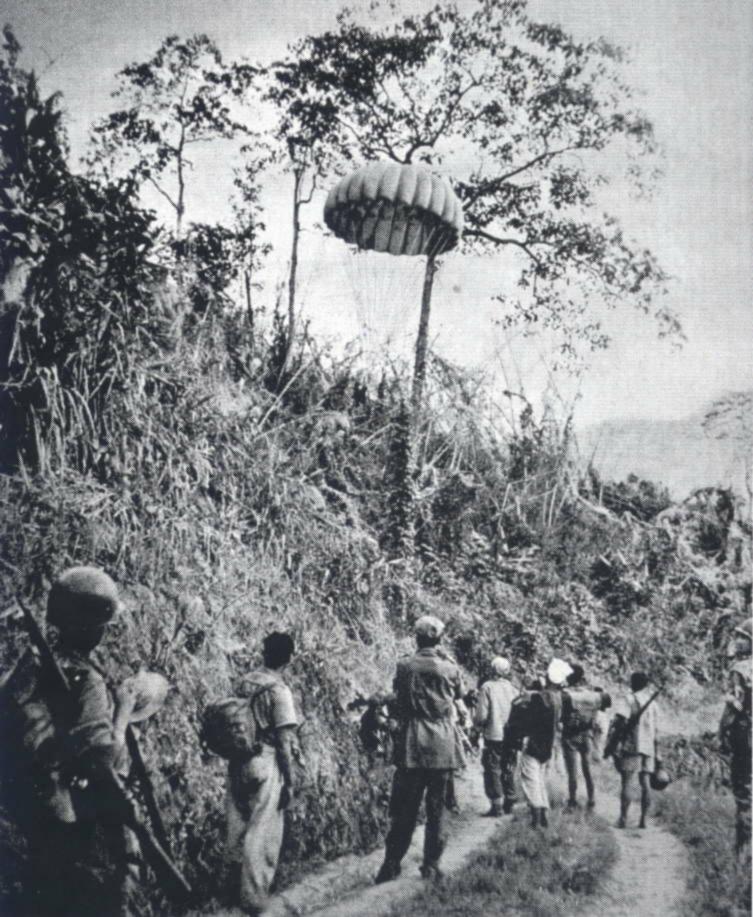

Finally, with winter coming on and with

pressure mounting from fellow members of the British Parliament calling

on the Anthony Eden Government to do something soon, the decision was

made to hit Egypt hard. With the Israelis on October 29th coming across

the Sinai Desert from the East, the British subsequently (November 1st)

attacked Egypt by air from their bases in nearby Cyprus and from navy

ships offshore from Alexandria. Then British and French paratroopers

were dropped several days later near the Canal in order to seize it

(November 5th). The Egyptians were quickly overwhelmed, their

casualties greatly outnumbering (about 100 to one) French and British

casualties. Militarily, the action was an immediate and grand success.

But politically the action was a grand

disaster. Members of the British Opposition (Labour and Liberals)

protested loudly concerning the sheer imperialism of the action. And

the move itself was not widely popular with the British public. In

fact, a huge public demonstration took place in London in opposition to

the action.

The Americans were also irritated greatly

by the action, because the British and French seizing of the Suez Canal

took place the very next day after the Soviet invasion in Hungary.

America was trying to score major diplomatic or simply ideological

points against the Soviets for their brutal crushing of the Hungarian

national spirit. But the behavior of its allies Britain and France in

Egypt looked much the same, thus undercutting deeply this diplomatic

opportunity to score huge ideological points concerning Soviet bullying

of smaller nations.

Furthermore, any support America might

have been willing to show its allies Britain and France Eisenhower knew

would merely alienate the Arab world all the more, even possibly drive

that world into the arms of the Soviet Russians.

Khrushchev, naturally, was deeply pleased

by this English and French action, because it diverted world public

opinion away from his heavy-handed move against Hungary. In fact the

early action in late October and the first days of November by the

Israelis, French, and English in Egypt helped him immensely to come to

the decision to undertake that move in Hungary. Thus it was that on the

4th of November he had sent those 2,500 tanks and 120,000 soldiers to

Budapest to crush the Hungarian rebellion.

Oddly enough, both America and Russia

brought resolutions before the United Nations Security Council calling

for an immediate ceasefire in Egypt – and for an Israeli, British and

French withdrawal from Egypt ... with both resolutions vetoed by the

British and French.3

Meanwhile, with the Suez Crisis dragging on, Eisenhower took an even

stronger stance against America's British and French allies, worried

that this event gave the Soviets the opportunity to move into Egypt as

Nasser's new friend and protector, even to come out threatening the

West with Soviet nuclear reprisals if Israel, Britain and France did

not immediately withdraw from Egypt. NATO commitments would necessarily

draw America into such a war, something that Eisenhower wanted to avoid

at all costs. Fearing just such a scenario (Eisenhower truly believed

that Khrushchev was just crazy enough to do exactly that), Eisenhower

now put huge pressure, including threats of economic reprisals, if the

British and French did not immediately pull back from the Egyptian

venture.

Facing such enormous pressure, Eden's

British Government finally capitulated, and was forced to acknowledge

what America itself demanded: British (and French) recognition that

Nasser's Egypt was indeed now the owner of their canal.

In the end only the Soviet Russians and

Nasser's Egypt gained from this event. Russia had moved quickly to pose

itself as the Arabs' best international friend. And Nasser now became

the Arab hero of the Middle East for his standing up to the European

imperialists.

America meanwhile, because of its

Israeli-Arab neutrality, gained no new advance of its position in the

Middle East through its behavior in this crisis. Eisenhower's attempt

to look like the friend of the Arabs failed to impress the Arab world,

which now looked more to the Soviets as their friend in their efforts

to get out from under European domination. At the same time

Eisenhower's heavy hand against his British and French allies weakened

tremendously the appearance of NATO as a solidly-united military front

lined up against Soviet expansion.4

And America's allies were hugely

embarrassed both at home and abroad. The whole thing was very

demoralizing to America's European allies – who were already suffering

from a deep sense of loss of national dignity.

And perhaps most importantly, it allowed

the Soviets to deflect the hostility that the world otherwise would

have felt towards the Soviets in reaction to their brutal behavior in

Hungary. Indeed, at a deeper level, it reminded the world that even

under Khrushchev, the Soviets were still a major superpower, one that

the world needed to respect in order to survive and thrive.

French Indochina

French Indochina Stalin dies... and a workers' uprising in East Germany results (June 1953)

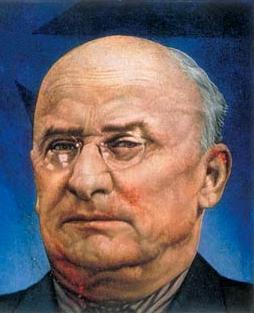

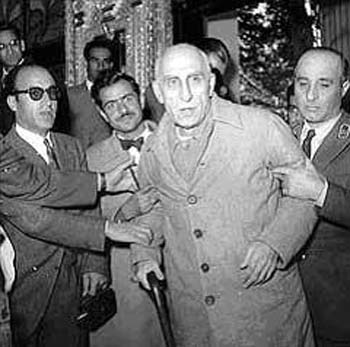

Stalin dies... and a workers' uprising in East Germany results (June 1953) The 1953 Iranian coup d'état

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état Khrushchev ... and the Hungarian uprising (October-November 1956)

Khrushchev ... and the Hungarian uprising (October-November 1956) The Suez Crisis (October-November 1956)

The Suez Crisis (October-November 1956) American paternalism in the Western Hemisphere

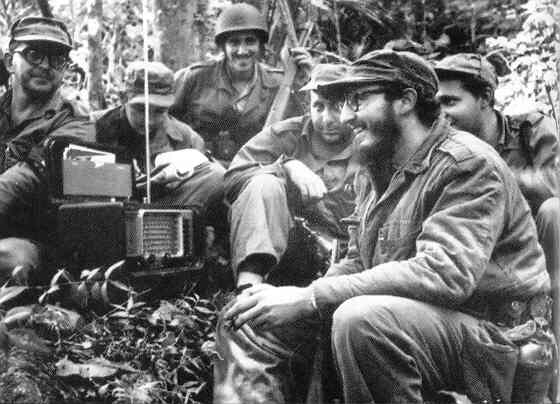

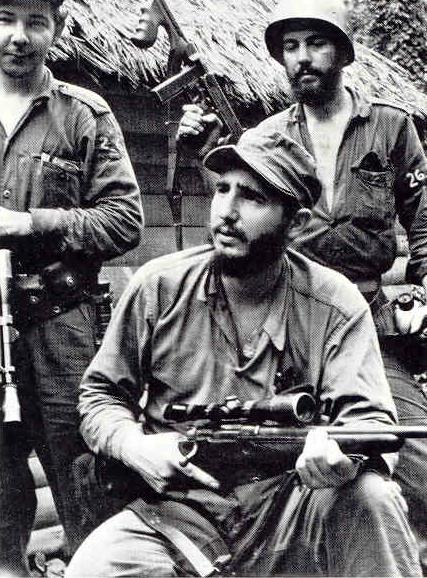

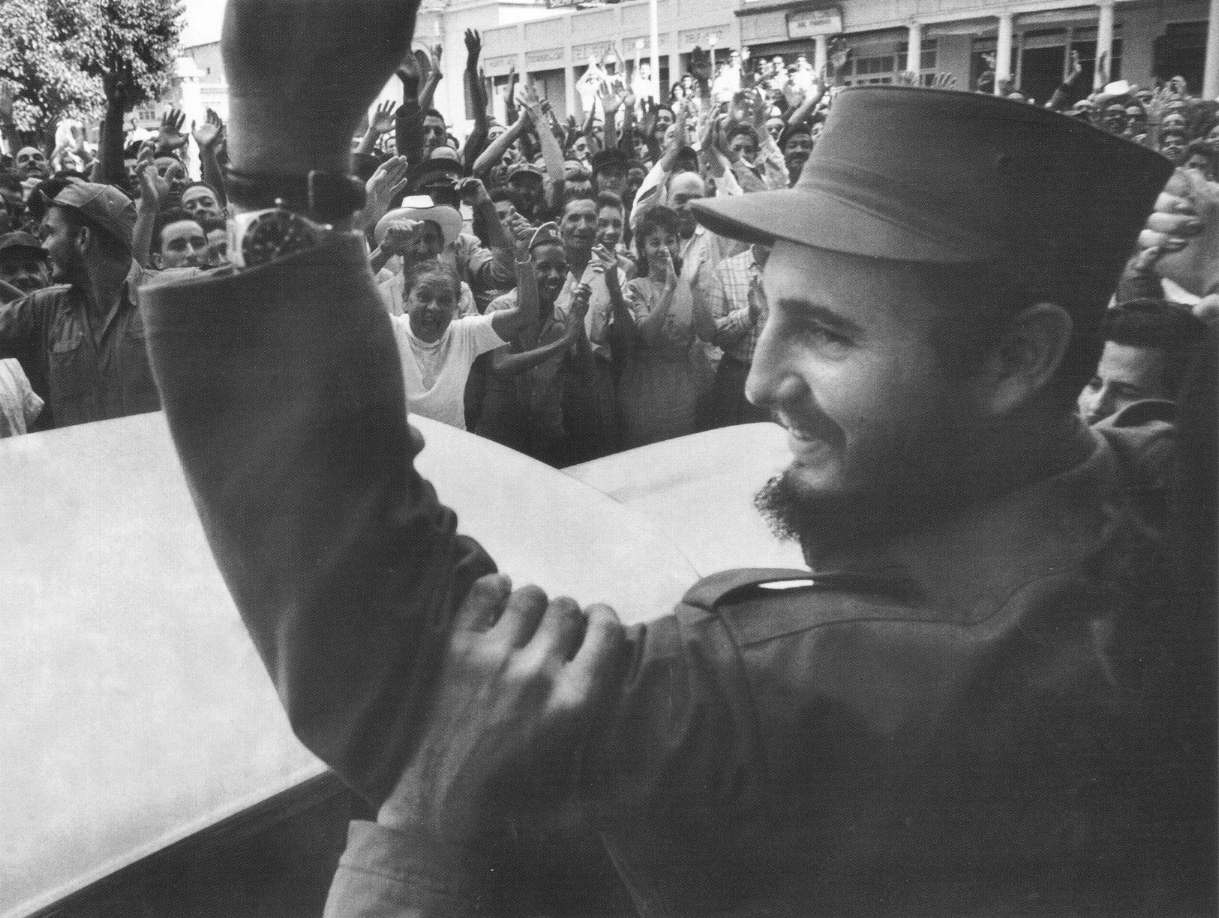

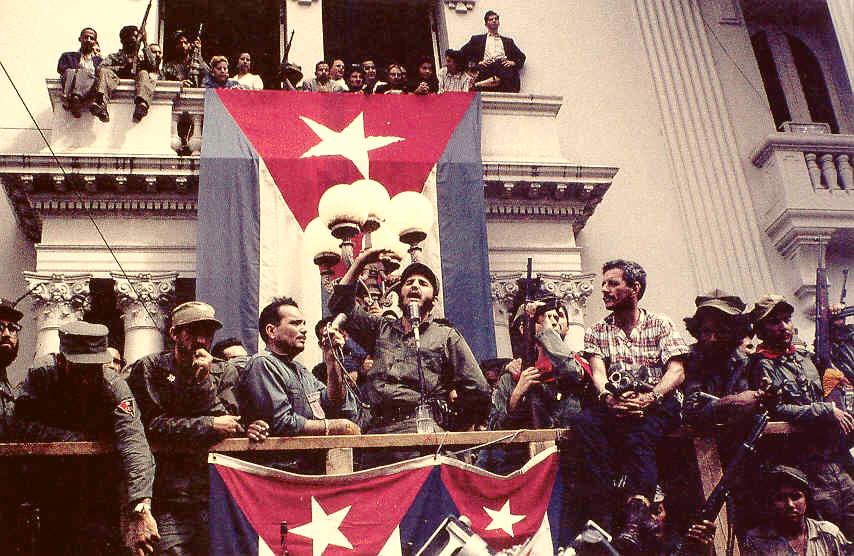

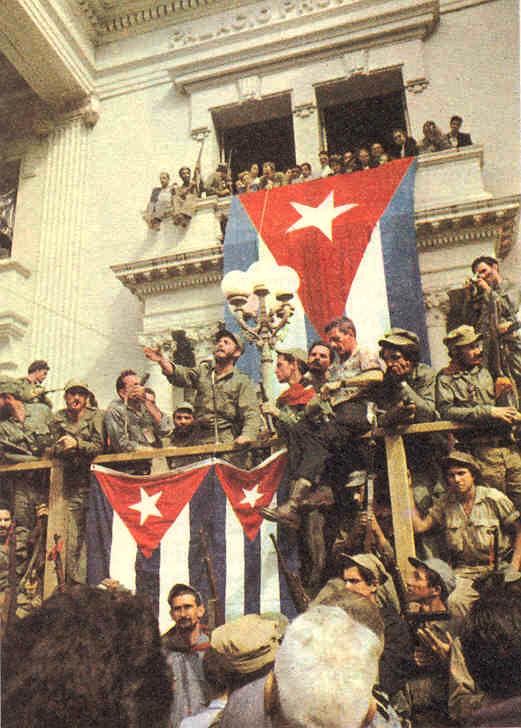

American paternalism in the Western Hemisphere  Castro's revolution in Cuba

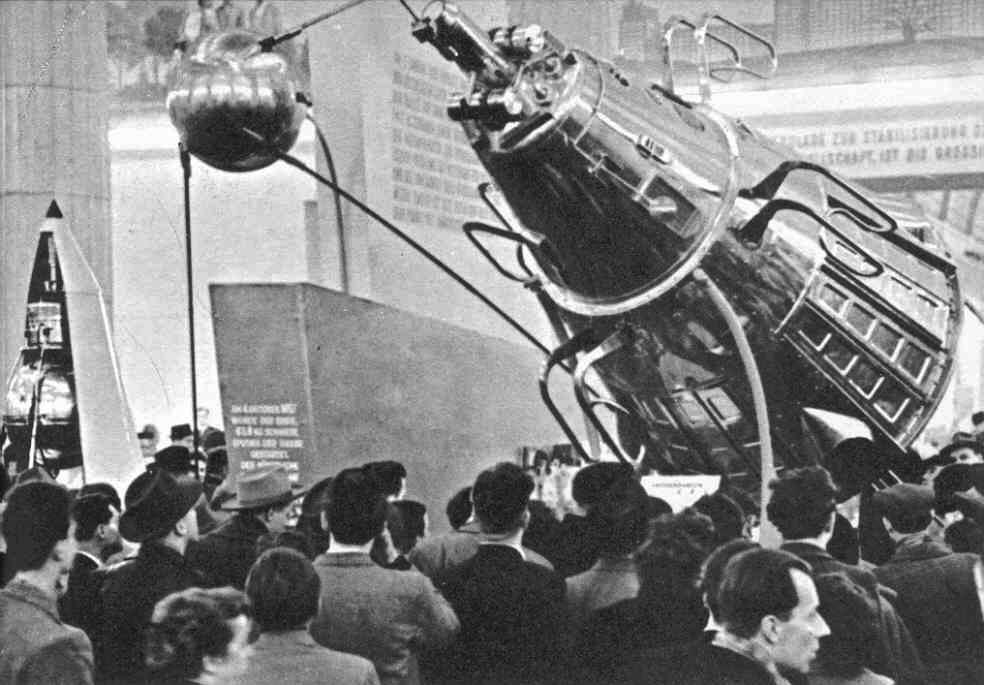

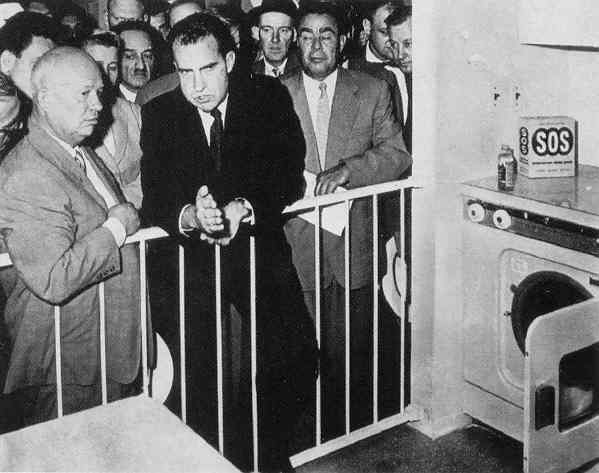

Castro's revolution in Cuba  Sputnik – followed by a "thaw" in East-West relations

Sputnik – followed by a "thaw" in East-West relations Christian America ... as it is about to head into the 1960s

Christian America ... as it is about to head into the 1960s

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges