|

|

The

young, energetic, handsome Kennedy becomes President The

young, energetic, handsome Kennedy becomes President

The Congo Crisis The Congo Crisis

South Africa's ethnic disputes South Africa's ethnic disputes

The

Soviets launch the first man into space – April 1961 The

Soviets launch the first man into space – April 1961

The

failed East-West Summit – June 1961 The

failed East-West Summit – June 1961

The

Berlin wall goes up – August 1961 The

Berlin wall goes up – August 1961

The

Cuban Missile Crisis – October 1962 The

Cuban Missile Crisis – October 1962

Kennedy

again attempts a soft approach to the Cold War – summer (1963) Kennedy

again attempts a soft approach to the Cold War – summer (1963)

Nasser

– and growing tensions in the Middle East Nasser

– and growing tensions in the Middle East

The

mounting crisis in Vietnam The

mounting crisis in VietnamThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 142-161. |

|

|

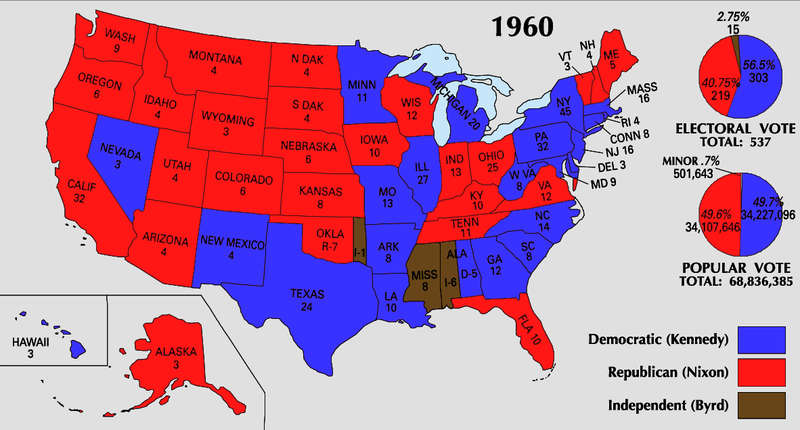

America knew that it was not a perfect country, but certainly understood what perfection should look and feel like, and indeed sought growth toward that ideal. The Cold War raging in the 1950s and early 1960s made this imperative. To win the hearts of an emerging Third World, to keep the Third World nations of Asia, Africa and Latin America from falling under the Communist program emanating from the Russian Kremlin, America needed to present to the world as positive a face as possible in order to win these newly emerging nations over to the "Free World" community of nations led by America. The 1960 Democratic Party presidential nomination Coming into the 1960 presidential election, it looked fairly clear that Vice President Richard Nixon would receive the Republican nomination. Only New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller seemed to be a possible challenger, except that he let it be known early on that he had no intentions of running for the position. Thus Nixon was easily nominated as the Republican candidate at the Chicago Convention. America’s U.N. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., was selected to be Nixon’s vice-presidential running mate. On the Democratic Party side, the situation was much more fluid. Adlai Stevenson tried again for the nomination, but could not get much traction on this third attempt. Texas Senator Lyndon Johnson, the powerful Senate majority leader, sought the nomination, and brought solid-South or "Dixiecrat" support with him to the Los Angeles Convention. But the front runner virtually from the start was the charismatic John F. Kennedy, Massachusetts senator and leading member of the rich and ambitious Kennedy clan, run by John’s father, Joseph Kennedy, Roosevelt’s one-time American ambassador to Great Britain (appointed by Roosevelt to get him out of the country and out of Roosevelt’s way!). Helping advance John’s political career was his brother, Robert, who had been serving as legal counsel to a number of congressional committees, but who had also served as John’s campaign manager as far back as John’s initial run for the U.S. Senate in 1952. The brothers were close, and would remain close. As it turned out, Johnson was unable to get any significant amount of support outside of the South, and Kennedy went on to gain the Democratic Party nomination. But Kennedy then asked Johnson to be his running mate – and Johnson accepted. Kennedy needed the Southern vote to edge out Nixon, who had strong support across much of the rest of the country, except among a number of old guard urban bosses and state governors, who lined themselves and their political organizations behind Kennedy. John Fitzgerald Kennedy John Fitzgerald Kennedy was second of nine children born to the very prosperous and politically active Irish-Catholic family of the Kennedys of Boston. John’s grandfather on his mother’s side, "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, was a Democratic congressman and two-term mayor of Boston, and his grandfather on his father’s side, Patrick Joseph (PJ), was a businessman active in Massachusetts Democratic Party politics, a political opponent of John’s other grandfather! John’s father, Joseph, continued the family’s activity in Massachusetts Democratic Party politics, as well as make a huge fortune in the 1920s in stock market and real estate investments and in Hollywood movie production, surviving the stock market crash by getting out of his investments ahead of time, and then in the 1930s, with Prohibition ended, moving into the whiskey import business. Joseph Kennedy was a major financial supporter of Franklin Roosevelt in his march to the White House in 1932, and Roosevelt rewarded this support in 1933 by appointing Joseph Kennedy as head of the new Security and Exchange Commission (SEC), assigned the task of cleaning up illegal stock market activity. Two years later, Joseph would change jobs, heading up the Maritime Commission. And three years after that, he would be appointed by Roosevelt as U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. Thus young John Kennedy would grow up in a world of privilege and power. But he worked hard to meet the family’s expectations of high performance in all walks of life. He was educated at a number of Catholic private schools before entering the prestigious but Protestant (largely Episcopalian) Choate boarding school for his high-school education. Then like his father, John would attend and graduate from Harvard (1936-1940). During this time, he traveled abroad extensively (not merely West Europe but also the Middle East and Soviet Russia) and developed a very strong interest in international affairs, writing a Harvard senior thesis critical of English diplomacy in its dealing with Hitler, which was published in 1940 as a best-seller, Why England Slept. But, unknown to the public, John Kennedy suffered from a wide variety of deeply serious health problems, the most critical and lasting being constant back problems. This would keep him from being accepted into the army’s Officer Candidate School in 1940. But after some considerable exercising (and some inside help from his father) he was able to get into the U.S. Naval Reserve, soon an ensign and a member of the Office of Naval Intelligence staff in D.C., just shortly before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in late 1941. The next year he received extensive torpedo-boat training, becoming at the end of the year a trainer himself, before receiving in April (1943) the overseas assignment in the Pacific Solomon Islands of commanding a number of PT boats in active war service. In August of that year his PT boat was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. But Kennedy and his surviving crew were able to swim (three miles) to shore, Kennedy bravely towing a badly wounded crew member – at the same time that his own back was badly injured. He returned to service in September, and helped rescue a number of marines stranded on a Japanese-controlled island. But in November he was sent to the hospital to begin treatment for his back injury. This was a very tough time for Kennedy, his older brother Joseph, Jr. being killed in Europe the following year, and he himself having to spend much of the rest of the war hospitalized for back treatment. He was finally discharged from the Navy Reserve as a naval lieutenant (March 1945). But he was able to carry himself admirably with a substantial number of military decorations. Being a talented writer, he (with his father’s help) gained a position with the Hearst papers as a special correspondent, even getting to cover the famous Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945. But with his older brother’s death, Kennedy’s father had other plans for his second son, John. The Kennedy family plans had originally been for Joe, Jr., to enter American politics, and reach even as high as the U.S. presidency itself. Now the family turned to John to take up that responsibility. John’s father was ready to invest considerable sums of money in support of John’s entry into national politics. That opportunity came with the 1946 Congressional elections in which the incumbent Congressman stepped aside to become Boston mayor, allowing John to run for, and ultimately win (quite substantially), the election for the 11th Congressional District of Massachusetts. Thus John Kennedy’s long march to the White House got underway. As a freshman Congressman, he was appropriately supportive of the fellow Democrat U.S. President Truman, taking a special interest in the growing Cold War. But even well before the beginning of his third term as Congressman, he began laying the groundwork for a senatorial run in 1952. In this he would be seeking to upset the incumbent "Boston Brahmin" (member of Boston’s long-standing ruling class) Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., whose political ancestry reached back even before the beginning of the 20th century (Lodge’s grandfather of the same name had become a U.S. senator back in 1893 and head of the Senate in the early 1920s). Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., had been a U.S. senator since 1937. It would be a tough race. But Kennedy worked hard, and actually succeeded that November in defeating Lodge with a relatively high majority of the votes (the extensive Roman Catholic population of Massachusetts helping him considerably). During his 1952 campaign, Kennedy met the sophisticated Jacqueline Bouvier, like himself a skilled journalist, and very good-looking in a Hollywood sort of way. She also was well-traveled abroad – as well as quite fluent in French (considered at the time to mark someone as a true aristocrat) and sophisticated in more a French than Middle-American manner. They dated, and following his successful run for the U.S. Senate he proposed marriage. She however did not give him an answer for some time – until she returned from her coverage of the coronation of the very young British Queen Elizabeth (June 1953). They would be married that September at Saint Mary’s Church in Newport, Rhode Island, with Roman Catholic Cardinal Cushing presiding. It was a major story, appearing on the society pages of America’s newspapers. Unfortunately, tragedy that seemed to accompany Kennedy success hit the young family hard, Kennedy being forced to undergo (and nearly dying from) spinal surgery in late 1954, and Jacqueline suffering a miscarriage (1955) and a stillbirth (1956) before she was finally able to give birth to a healthy daughter, Caroline, in 1957. Nonetheless, Kennedy was a rising star. And at the Democratic National Convention of 1956, after delivering an excellent nominating speech for presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson, he came in second in the vote for Stevenson’s vice-presidential running mate. Even at that, Kennedy now had national political recognition, helping advance his career considerably. This helped him gain a very easy re-election in 1958 to a second term as Senator. At this point he began to lay out a strategy for a run for the U.S. Presidency in 1960. He was able to win some key Democratic Party primaries going into the national convention. But it was still a time in which party bosses controlled most of the votes at the convention and Senator Lyndon Johnson was a well-known behind-the-scenes operator. Going into the convention Kennedy had the largest number of first-round votes, but knew that if he did not get the nomination on that first round, Johnson would probably be able to swing the convention his way after that. But as it turned out, Kennedy was able to gain the majority he needed to receive the party’s presidential nomination on that first ballot. Then, to the surprise of many (and the irritation of his brother Bobby, John's campaign manager), Kennedy asked Johnson to become his running mate. It would be a very close race against Republican Vice President Nixon and Kennedy would need the swing vote of the South where Johnson was from, and where Johnson commanded a lot of support. The presidential campaign that year would be the first time that presidential debates would be presented via television, and it would work greatly to Kennedy’s benefit. During the all-important first debate (of four), Nixon did not present himself visually in the cool format that Kennedy was able to project, and such imagery would become increasingly important in the way Americans would henceforth evaluate candidates.1 The debate turned on Nixon’s citing his own eight years of executive experience as Vice President, plus the promise to continue down the same prosperous path that the country had experienced during the Eisenhower years. Kennedy countered by pointing out that America had been allowed to fall behind the Soviet Russians in the vital technology race, and by promising that as President he would push hard to get America back into the lead in the space race. As he campaigned, having his attractive wife Jacqueline often at his side during the campaign merely added all the more to the sense of sophistication that accompanied the Kennedy presence. His Catholicism was of some concern to largely Protestant America. But he was quick to point out that he was not campaigning on behalf of the Church, and that his Catholicism had not been an issue to anyone back when he served his country in the South Pacific! Actually, Kennedy’s religious loyalties remained largely unknown to Americans (even while president). He was indeed a loyal member of the Irish-Catholic world, although this seemed to be more a matter of social identity than any particular personal theological conviction. He followed fairly closely the ritual requirements of the Catholic Church (principally, regular in his attendance at mass) but not so much its moral disciplines. Also unknown to Americans at the time, and even long after, Kennedy was a compulsive womanizer with an insatiable appetite for mistresses, usually of the higher reaches of society, including Hollywood (even the famous Marilyn Monroe). Kennedy would bring God into his public pronouncements in a way Americans at the time expected their presidents to do so. But where he actually stood personally with God was not really known to anyone other than Kennedy himself. His close associates, including for instance his personal advisor Ted Sorenson, remained unaware of Kennedy’s exact position on such matters as heaven and hell and life after death. Certainly Kennedy lived a life of prayer, personal pain as well as political pain being a big part of his life. But that seemed to have no impact on his extensive womanizing (which at the time was considered by the Washington press and Congressional membership to be nobody’s business other than the president himself). Kennedy was thus a very private Catholic. And Americans truly had no cause to believe that he would, as a good Catholic, bring America under Rome’s papal authority. Anyway, with the grand religious council held in Rome known as Vatican II (1962-1965), the political requirements of "good Catholics" to come under Rome’s political jurisdiction was put aside in support of a wider acceptance of the legitimate place of other members of the Christian world (meaning, among other things, that non-Catholics were no longer destined at death to go to hell!). In any case, the November (1960) presidential vote was close2 – very close indeed, with Kennedy gaining 49.7 percent of the vote and Nixon 49.5 percent. The crucial electoral college majority, however, would register as a bigger difference, with Kennedy’s 303 votes to Nixon’s 219. Kennedy was thus elected as the country’s thirty-fifth president. 1Just prior to that first broadcast, Nixon had rushed in from a campaign meeting and had not put on makeup (Kennedy had) needed to keep him from looking washed out under the glaring T.V. lights. Nixon would not repeat that mistake. But first impressions really stayed with people who thought Nixon looked uncertain and even anemic. Radio listeners however thought Nixon had sounded the more solid of the two debaters – although at this point the TV audience (some 70 million Americans) vastly outnumbered the radio audience. 2There

were serious questions about how Mayor Daily brought in the Illinois

vote for Kennedy. But Illinois going to Nixon instead of Kennedy would

not have changed the ultimate outcome.

|

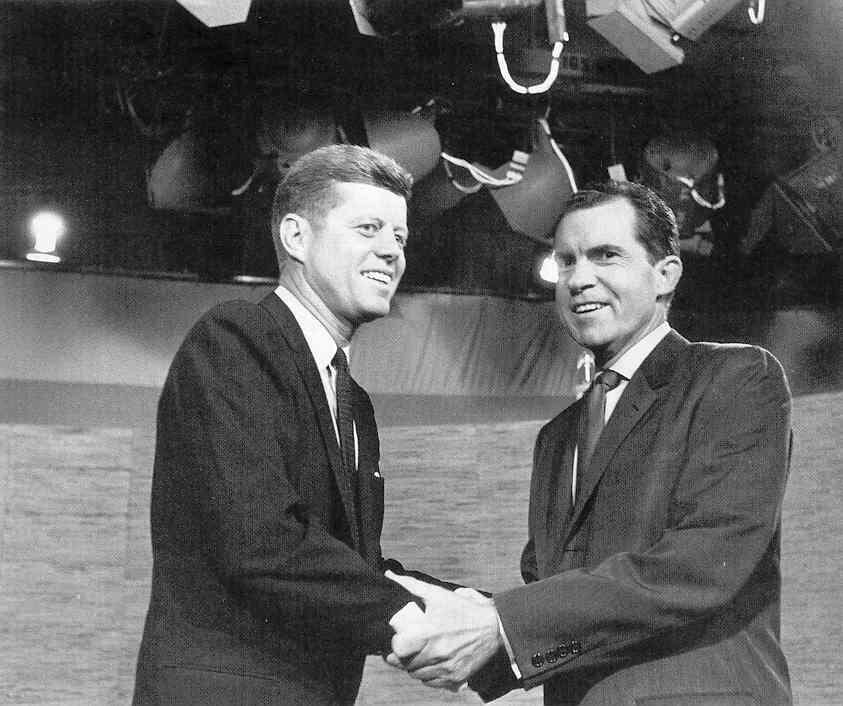

John Kennedy and Richard

Nixon before they begin the TV-radio debate series – 1960

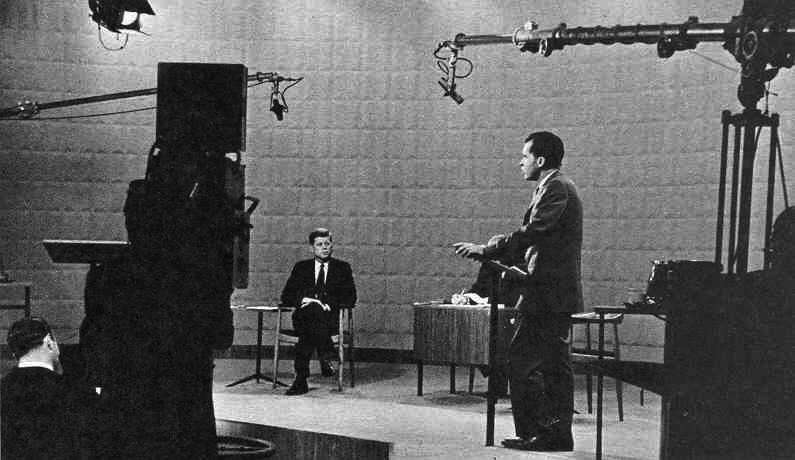

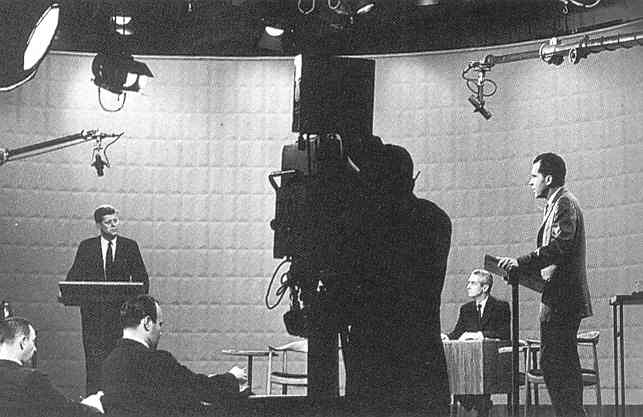

Nixon debating Kennedy -

1960

The Kennedy – Nixon Debates - 1960

Some of the Kennedy Clan

- just after JFK's election to President – November 1960

(Seated from left: JFK's parents,

Mrs. (Rose) and Mr. Joseph Kennedy; his wife Jacqueline;

his brother Edward; standing from left: Mrs. Robert

(Ethel) Kennedy; brother-in-law

Stephen Smith; Mrs. Smith; JFK; Robert

Kennedy; sister Mrs. Peter Lawford;brother-in-law

R. Sargent Shriver; Mrs. Edward (Joan) Kennedy; brother-in-law Peter Lawford

John F. Kennedy (1917-1963)

at the podium

President John F. Kennedy

- 1961

|

The term "Camelot" is often

used to describe the sheer elegance

of the Kennedy White House

John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline

Bouvier just prior to their wedding in 1953

Camelot: the splendor

of the Kennedy's

The Kennedy Style:

Pablo Casals performing in the East Room of the White House

|

Kennedy's fondest hope is

to take up the Soviet challenge through a new spirit of cooperation with

emerging nations around

the world: to show them the American way to freedom and development

|

In his Inaugural Address (January, 1961), at age forty-three, the youngest American to be elected president ever (following its oldest president up to that time),3 he both explained and personally symbolized the arrival of a regime of very new ways in which America under his leadership would approach the challenges then facing the country. He called on Americans to approach the world in a very new way, to see before them a "New Frontier" both at home and abroad. America’s youthful spirit (mirroring his own) was going to revolutionize the world. He spoke of the immense danger that nuclear weapons and the arms race posed, not only to the country but also to the world, and how America needed to back away from these conflicts and instead take up a more positive approach to the world and its issues. He called for a new East-West spirit of unity in refocusing international efforts away from war and directing them instead to the major problems of poverty, disease, and dictatorship that afflicted the world. In short, Kennedy called on Americans to look to a more positive approach to American diplomacy, promising that a better world would result. He also spoke his most memorable and

famous line: "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you

can do for your country." His call for Americans to take up their

greater responsibilities would find Vets in the audience agreeing

heartily. But that line would make no sense to the rising Boomer youth,

who would approach life in every way possible from exactly the opposite

direction: what does society owe me? But at this point the first of the

Boomer generation were just entering their teenage years, not yet in a

position to turn American culture upside down. The Peace Corps Kennedy had been in office only a little over a month when on March 1st, in pursuit of the ideals declared in his inaugural address, he issued an Executive Order calling for the creation of a new program (actually thought up by Senator Hubert Humphrey) challenging America, in particular its youth, to help spread the understanding of "The American Way" around the world, by volunteering as members of a new Peace Corps. University-educated Peace Corps volunteers were to take their places in the ranks as patriotic Cold Warriors, not as soldiers, but as cultural missionaries sent out to show villagers around the world what America was like up close – to go and live among the people of the Third World in order to show them personally how American ideals worked to make for a better life. This would not become a massive, expensive government program. No huge Washington bureaucracy would provide the muscle for this program. Instead it would rest on the support of the thousands of young volunteers who answered the call to national duty (they did receive the equivalent of army basic pay, which indeed was truly "basic.") It was typical of the way that Americans felt at that time that the nation should go about its business, challenging the average American to do the right thing, to volunteer to take up the national cause, just as the nation should inspire (not dictate to) the world to do the right thing. The Washington government’s job was simply to organize the opportunities for Americans to do the right thing, nothing more. Washington itself wasn’t expected (not yet, anyway) to do the right thing for the people. The "Silent Generation" respond Answering the call to Peace Corps service were thousands of young college grads, members of the very patriotic Silent Generation. They were quite unlike their younger brothers and sisters, the Boomers, who would eventually arrive on the political scene as noisy and aggressive crusaders against virtually everything their Vet parents held dear. Although this older generation of youth had been put under some of the anti-authoritarian programming of the mid-1950s that their younger Boomer siblings had been, these "Silents" were already in their teens at that point and fairly well developed along lines much closer to the Vet parents' social values. These were not rebels but instead idealistic joiners, believing very much in the American message for the world, and eager to be sent abroad to show personally to Africans, Asians and Latin Americans the "American Way" they had grown up in.4 The birth of the hippie counter culture Ironically the process of cultural

missionary work would however often end up going in the direction

opposite the one intended by the Kennedy Idealists. Many of the

youthful Peace Corps volunteers would "go native" in their two years

abroad, seemingly absorbing as much as or even more than their giving

in the cultural exchange. Many volunteers would return to America

more interested in living close to the soil the way the peasants they

had been living among went about life. The simple life, by

comparison to the complicated life of Middle America, indeed had its

major attractions. And thus many of these idealistic youth would

come to take up the "hippie" communal lifestyle, rejecting the

competitive, upwardly-aspiring Middle-Class lifestyle of their parents,

hoping to find in the communal life a serenity that they felt was

lacking in American culture. The naive assumption that the world naturally could be, On the other hand, most of the world stood in envy of American prosperity, its huge material wealth, its glitzy lifestyle (by comparison to the world’s humble, largely peasant lifestyle). But envying the American lifestyle and choosing to emulate that lifestyle, even being able to do so, were two quite different things. America could not appreciate the fact

that the Soviet model offered to the political leadership of the Third

World a kind of efficiency or developmental speed in moving from

feudal, agricultural backwardness to industrial dominance in a single

generation (as in Stalin's Russia). American-style capitalism seemed

complicated and required the presence of certain social attributes and

personal skills (especially personal initiative and willingness to take

risks) that just did not exist in these Third World countries. 3Teddy Roosevelt was younger than Kennedy when he took office as President, but did so only on the basis of stepping up as former Vice President into the presidency when President McKinley was shot. 4In

terms of national leadership, this generation will be skipped over, as

presidential leadership would in 1993 pass from the last Vet, George

H.W. Bush to the first Boomer, Bill Clinton, 22 years younger.

Prominent "Silents," born in between those two quite different

generations, would include Newt Gingrich and John McCain – highly

patriotic presidential material ... individuals however who were not

quite able to interest the vote of the Boomers – or the Generation-Xers

that followed the Boomers.

|

The Kennedy brothers – close

confidants

The US Peace Corps becomes the symbol of Kennedy's New Look

A Peace Corps Volunteer in

Accra, Ghana, with his students

President John Kennedy greeting

Peace Corps volunteers – 1962

|

Tragically this "new look" is set off

on the wrong foot

by the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba – April 1961

|

The Bay of Pigs Fiasco (April 1961)

Almost immediately, Kennedy’s New Frontier philosophy was put to its first moral test. Kennedy was rather surprised to learn that a huge 1,400-man militia of Cuban expatriates had been in training for the eventual overthrow of the troublesome Cuban President Fidel Castro, and in fact was scheduled for an assault on Cuba soon after Kennedy took office. The date for the action was already set for mid-April 1961. But Kennedy had campaigned on a peaceful rather than aggressive approach to winning the Cold War contest over the rising Third World. An American-sponsored invasion of Cuba would make a complete mockery of that very idea. Yet on the other hand, Castro was clearly opening up Cuba to massive Soviet influence – right off the American shores of Florida. Something needed to be done to reverse that development. But not seeing any alternative to the plan in place, the new President Kennedy gave the event the go-ahead. But Kennedy wavered when the involvement of America was made increasingly obvious. On the third day of the operation Kennedy called off further American air cover and naval resupply of the invading militia, leaving the ammunition-less anti-Castro militia to face the fury of a retaliating Cuban tank corps. It was a humiliating defeat for the militia, taken prisoners and paraded in front of the world press. And it was also a grand humiliation for America, and for the new President, who did not come away looking anything but weak and irresolute in the face of the Cold War contest still raging. Kennedy’s youthfulness thus seemed confirmed not only by his looks but now also by his behavior.

|

A CIA-sponsored military

training camp for Cubans committed to the overthrow of Fidel Castro

(most of these camps were

located in Florida)

A scene of the military fiasco

at the Bay of Pigs, Cuba – April 17, 1961

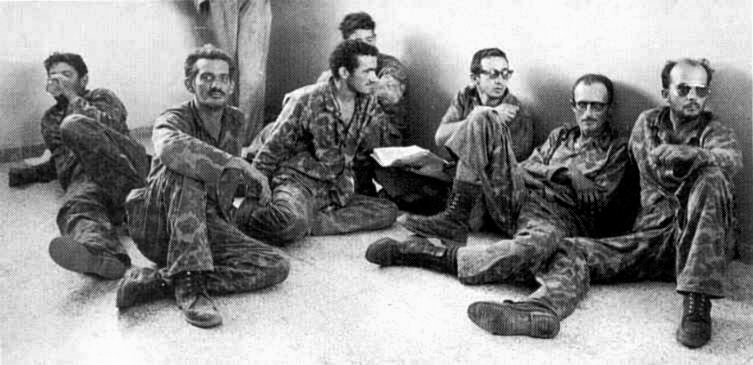

Part of the 1500 member anti-Castro

paramilitaries captured at the Bay of Pigs – April 1961

CIA-trained Cuban "liberation"

soldiers captured at the Bay of Pigs

Castro inspects the wreckage

of an American plane that crashed at Playa Giron – April 1961

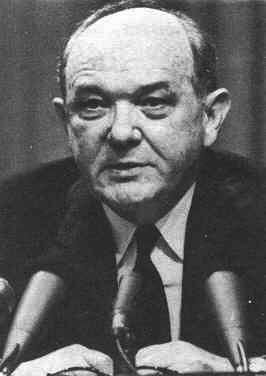

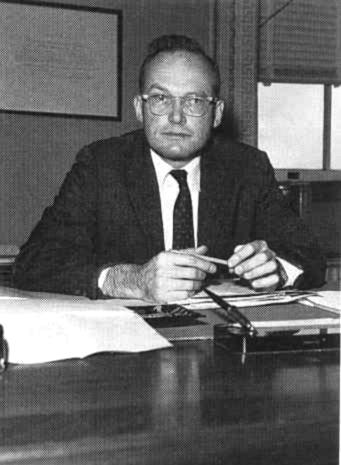

Dean Rusk

U.S. Secretary of State:

January 1961 – January 1969

|

|

The latter part of the 1950s saw Europe’s African

colonies wanting to move to national independence. That was not going

to be easy, because when the European powers distributed African

colonial territories among themselves (principally at the Berlin

Conference of 1884-1885), colonial borders were drawn up without any

consideration of the tribal or ethnic lines that divided Africans

locally. Some tribes were divided, with some part of the territory

assigned to the English, some to the French, some to the Portuguese.

Some tribes (even former enemy tribes) were lumped together as part of

this or that European colony. Ultimately what determined the colonial

boundaries had nothing to do with African political dynamics themselves

but instead simply a way of balancing European imperial power by some

kind of equitable assignment of African lands to this or that European

power. Now as the 1960s approached, local leaders (Africans who were European-educated for the most part, but still identified locally as a member of this or that African tribe) began to call for the independence of their "nation." Immediately this threw local African politics into something of a turmoil, as local Africans saw such a move as merely the opportunity of one tribe to place itself in a position of dominance over other local tribes enclosed within these European-created "national" boundaries. For instance, Nigeria as a nation was definitely more of a British concept than a local understanding, where local inhabitants of this British colony saw themselves mostly as Hausa, Fulani, Yoruba, or Ibo – not "Nigerian." But in general, the transfer of power from European to African in the late 1950s and early 1960s was transacted fairly smoothly, by carefully putting the country’s power in the hands of a strong local leader, often perceived in America as simply a dictator, although America generally stayed out of the process. But it worked, mostly, as these new "nations" were granted independence and took their seats as new members of the United Nations Organization. The Belgians themselves were in no hurry

to grant independence to their Congo colony, Belgium being deeply

invested in the economy of its colony. But the process of gradual

introduction of local self-rule in 1957 simply opened the realm of

rapidly-rising expectations that always accompanies a shift in the

political status quo. But when deadly violence broke out in the Congo, the Belgians, hoping to calm the situation, moved fairly quickly to grant full independence to their colony at the end of June (1960). But this was only the beginning of the violence, for there were some 80,000 Belgians living in the Congo and local groups turned violently on these Europeans (similar to the treatment of Europeans in Dutch Indonesia and French Algeria). The United Nations was called in to help protect the Belgians, who at this point were scurrying to get out of the country. In their departure, the Belgians gave over their Congo colony in June of 1960 to a hopeful coalition of local Congolese leaders supposedly constituting a new Republic of the Congo. But this was the signal for a wide number of individuals, usually supported by a local tribe, to attempt to either take control of the new government – or simply try to break free from the new Congo and set up their regions as independent countries. To keep the Congo unified, Lumumba turned to the Soviets (who thus sent 1,000 military "advisers" to the Congo), alarming greatly the Americans. Meanwhile the Belgians, trying to keep some kind of foothold in the Congo, threw their support to mineral-rich Katanga Province leader Moise Tshombe. At this point U.N. troops were also trying to keep the country from falling apart. However, as the situation failed to improve with time, U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld tried personally to intervene, only in flying to Africa to have his plane crash (September 1961). Things then got even crazier. America then swung its support to Tshombe, convincing him not to separate the Katanga Province from the Congo but instead to take over the whole of the country (1963). This he did, settling things down (sort of) under his rather dictatorial rule. But Tshombe’s military commander Mobutu Sese Seko in 1965 decided that it was time to step in and take control of the country (whose name he changed to Zaire in 1971). Mobutu would remain firmly in power all the way up until his death in 1997! Lessons for America in African politics America got nothing out of the Congo crisis – except the understanding that there was very little America was likely ever to get out of African developments. In a sense Africa was Europe’s huge legacy. And whatever developed on that continent, especially in the Sub-Saharan or southern part of the continent, was Europe’s concern, not America’s. African countries were likely to be run by tribal dictators anyway. And America (other than, in a limited cultural way, its talented Peace Corps volunteers) would have no way of influencing the very strong political instincts of the African people.

|

|

|

The exception to this political hands-off policy would be the country of South Africa, long run by Dutch and English-speaking Whites. Much more was expected by Americans of those European descendants in their handling of South African politics. But those expectations were based on an amazing ignorance of any of South Africa’s actual social dynamics. The Dutch had actually moved into a sparsely settled South African Cape region back in the 1600s – just as the English were colonizing the sparsely-settled shores of North America. And this Dutch settlement in South Africa occurred also at precisely the same time as other Dutch were settling into the Hudson River, Manhattan, and Long Island region of what would eventually become New York! Somehow America, however, seemed to miss the comparison between these Dutch South African settlers who came to see themselves as "Afrikaners" and the Anglo settlers of New England and Virginia, who would eventually see themselves as "Americans." Indeed, 20th century Americans simply viewed the Dutch-speaking Afrikaners (and the later-arrival South African Anglos) as illegal occupants of a Black African continent. Actually, the tall Bantu Black Africans (mostly of the Xhosa and Zulu tribes) in their migration south along the Indian Ocean were themselves later arrivals to South Africa. And it was not until the mid-1700s that the two groups, Bantu Blacks and Afrikaner Whites, met – much to each other’s surprise! – about halfway across what is today South Africa. The original inhabitants of South Africa were not the Bantu but instead the San people (Bushmen and Hottentots), hunted like rabbits by the advancing Bantu. The San survivors took refuge among the more hospitable Dutch, learned their language, and today forming the Dutch-speaking "Coloured" ethnic component of South Africa – the descendants of the original but largely forgotten inhabitants of the region. But Americans simply chose to see all this South African dynamic as another version of its own growing Black-White problems arising at home in America, totally missing the complexities of the South African situation – a situation just about as complicated as any other of Africa’s political situations. For instance, the ancient hatred between the Bantu Xhosa and the Bantu Zulu was intense inside of the country, but overlooked entirely by the outside world that saw only "Black" and not Zulu or Xhosa. Then there was the matter of the huge Indian population of South Africa’s Natal Province – where Gandhi himself had practiced law for twenty-one years before heading off to India to save that country from the British. Few Americans had any idea that this huge Indian population even existed in "Black South Africa." And of course the White community itself was held together in a very precarious Dutch-speaking and English speaking union, in which the English seemed to have less an emotional foothold in the country (arriving at South Africa two centuries after the Dutch had made it their home) and thus more willing to be compliant before rising Black political expectations for mastery of "their African nation." To the Dutch-speaking Afrikaners, however, South Africa was certainly no less "theirs" than it was to the late-arriving Bantu. Anyway, Americans eased their own consciences deeply shamed by White mistreatment of Blacks in America itself – by becoming super zealous in attacking White South Africa for its "similar" racial prejudices. The fact that the South African and the American situations had little in common did not seem to matter, nor did it even stir the curiosity of Americans as to what was actually happening in South Africa. The Americans were well-pleased to keep the South African moral matter as simple as possible. Thus they could pronounce their own judgments on South African developments with a very clear (actually very muddled) conscience. Ultimately this served no one well, particularly the South Africans.

|

|

The Bay of Pigs fiasco is

timed with another American setback:

the Soviet's announcement

that they have launched the first man into space – April 1961

The Soviets continue to push ahead in the space race with a number of new "firsts"

Yuri Gagarin, first man in

space, April 12, 1961

Yuri Gagarin being greeted

in Moscow by Khrushchev

two days after his 89-minute

flight into space – April 1961

Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin

and Valentina Tereshkova – first man and first woman in space

Alan Shepard, Jr. – 1st American

into space – May 1961

(but unlike the Soviet flight

of Gagarin, Shephard did not orbit the earth)

|

In June of 1961 the Kennedys travel

to Europe in an effort to improve relations

with a distancing France and a threatening

Russia

|

Soviet premier Khrushchev had indicated quite clearly that the Soviets were going to push harder in aligning the rising Third World with the Soviet bloc, Castro’s Soviet-supported social revolution in Cuba and the chaos in the Belgian Congo's independence serving as examples of what America might expect from the Soviets. At the same time, Khrushchev announced a coming treaty with East Berlin, one which would end access rights from East Berlin into West Berlin. To try to defuse resurfacing Cold War tensions, Kennedy got Khrushchev to agree to a summit meeting in Vienna in June. But dealing with Khrushchev would not be a straight-forward matter. Kennedy was warned about Khrushchev’s very aggressive style, even by French President De Gaulle whom Kennedy visited on his way to Vienna. Ultimately the Vienna meeting did not go as Kennedy had hoped and, possibly even worse, confirmed Khrushchev‘s impression of Kennedy as a weak leader. The Soviet closing of open access to West Berlin thus moved forward as planned, despite Kennedy’s own announcement of a considerable beefing up of American NATO support in Germany.

|

The Kennedys with Charles

de Gaulle outside the Elysee Palace – June 1961

Kennedy Greets Khrushchev

in Vienna – June 3, 1961

Nina and Nikita Khrushchev

chatting with Jackie Kennedy in Vienna – June 1961

In his "summit" meeting with

Nikita Khrushchev (June 1961) Kennedy becomes aware

that a new test of East-West

resolve is about to occur over Berlin

|

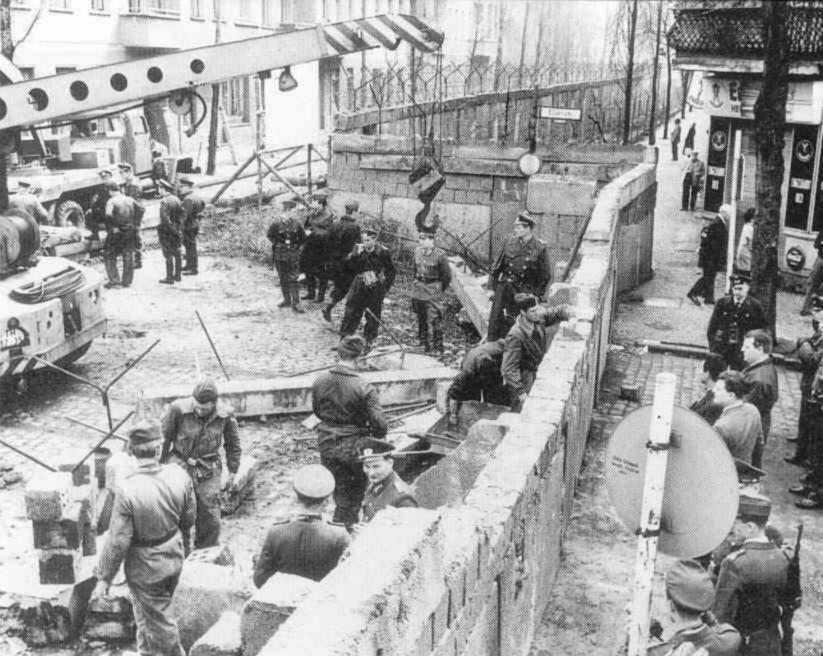

Thus Berlin once again serves as a measuring

device by which the Soviets test American

(Kennedy's) will power as the Soviets

build a wall around the city – August 1961

|

In the next weeks, tens of thousands of Germans poured from East Berlin into West Berlin in anticipation of the Soviet closing of access from East to West Berlin. Finally in mid-August East German soldiers began the erection of at first a barbed-wire then a concrete barrier (ultimately including armed guard towers and minefields) around West Berlin, closing off all further access from the East to the West of the city. The last open door offering escape from the Soviet side of the Iron Curtain was now completely closed. Much of the world watched in anticipation to see what Kennedy would have the Americans do in response. It soon became apparent that there would be no American response in terms of knocking down the wall. But Kennedy did make it a point to march NATO troops to West Berlin using the highway running through East Germany, daring the Soviets to try to block the continuing access of Western troops into West Berlin.

|

Barbed wire going up quickly

around Berlin – August 1961

An East-West standoff over

the Berlin Wall – August 1961

Watching East Germans put

the finishing touches on their own imprisonment

East German border guard

escaping to the West – August 13, 1961

Soviet-American tank standoff

at Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin – October 1961

Stand-off at the new Berlin

Wall – 1961

The Brandenburg Gate and

the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall – July

1962

Miles Hodges

The Berlin Wall – July

1962

Miles Hodges

The Berlin Wall as it passes

before the Brandenburg Gate

(29 miles long and 8 to

12 feet high)

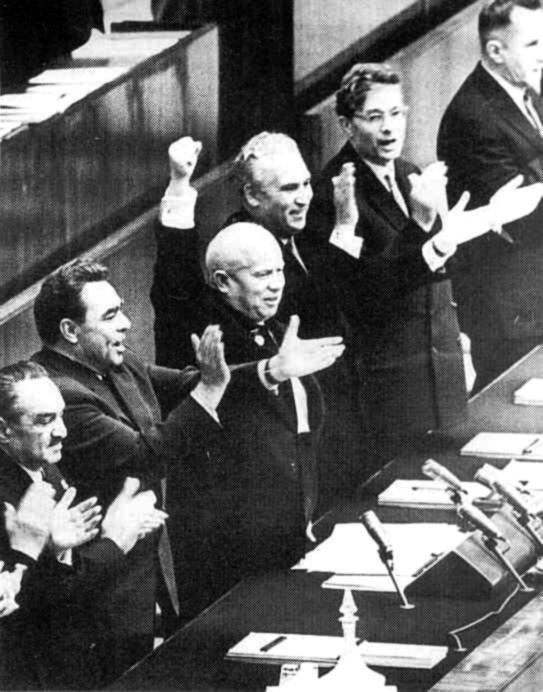

Khrushchev being applauded

at the 22nd Party Congress in Moscow – October 1961

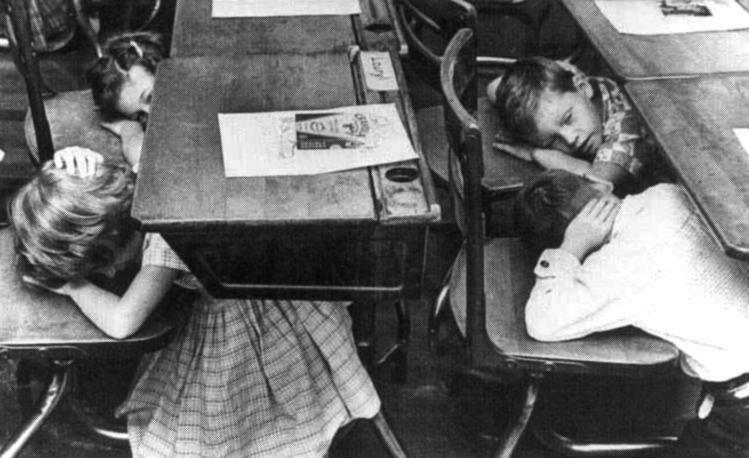

American children practicing

"duck and cover" drills as Soviet American tensions build, and

Americans come under a new fear of

a possible nuclear war with an aggressive Soviet Union

Kennedy finishes out the

first year of his presidency as a very tired man – December 1961

|

The weak Kennedy response

to Soviet challenges emboldens Khrushchev to try

to plant deadly nuclear

missiles in nearby Cuba – October 1962

|

Despite the abysmal failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy and the CIA had not ceased to plan to remove the Cuban threat posed by Castro’s Communist regime, and had undertaken a number of programs to isolate Cuba economically and destabilize the regime internally. These plans included a revolt within Cuba by disaffected Cubans (Operation Mongoose), supported of course by U.S. funding. Castro and Khrushchev quite naturally suspected such a U.S. maneuver, and Khrushchev saw an opportunity not only to thwart this operation, but to embarrass and weaken further the American international position by placing nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba, ones possessing fully a first-strike capability. This could be used as leverage to force America to back down, not only in the event of an American attack on Cuba but even elsewhere if need be – such as in the event Khrushchev wanted to try again to force the West completely out of Berlin. Placing Soviet missiles in Cuba would also neutralize the impact of the American nuclear missiles placed in Turkey and aimed at the Soviet Union. By the summer of 1962, Castro had come to the point of accepting this idea of placing Soviet missiles in Cuba, seeing in this the further securing of his own position not only as Cuban leader but also as a major sponsor of social revolution elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere. Within the Soviet hierarchy in Moscow itself there was considerable debate about the wisdom of such an aggressive move against America, as the Americans, compared to the Soviets, had a vastly greater number of long-range nuclear rockets and nuclear warheads (over 15 times the number of Soviet warheads) able to do widespread damage in case of a Soviet-American conflict. But Khrushchev was able to carry the day on the basis of his portrayal of Kennedy as a weak individual who would be forced to accept the Cuban missiles rather than take direct military action that would provoke all-out war. The net result of Soviet missiles based in Cuba would thus be a massive shift in the international balance of power in favor of the Soviets. Preparations thus got underway to first build the infrastructure of the launch sites where these Soviet missiles could be based. It would all be done in high secrecy of course – until the missiles were fully operational. But American U-2 spy-plane flights over

Cuba soon detected the infrastructure activity in Cuba (August) and

complained – but received from the Soviets in early September the

assurance that the installations being placed in Cuba were purely of a

defensive nature. But that merely raised the question within the

American intelligence community as to why defensive (short range)

missiles were necessary unless they were designed to protect something

of greater strategic importance, such as long-range missiles aimed at

the US. At the same time, fearing that defensive missiles might be used to bring down another American U-2 spy plane, further U-2 flights over Cuba were canceled. But American defense analysts were concerned that the configuration of these Soviet sites matched those of major nuclear sites within the Soviet Union itself, and finally got U-2 missions resumed a month later – although it was not until mid-October (the 14th) that the cloud cover over Cuba broke, allowing the Americans to detect finally what was really going on in Cuba. The next day President Kennedy was informed of the problem, and the day after that Kennedy convened his national security team to discuss the situation and consider the American options, none of which were very good. Some, such as Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, argued that the small number of Soviet missiles placed in Cuba would not affect the balance of power significantly. But others argued that failure to act would further weaken the appearance of American power and undercut the reputation of America as a reliable defender of its NATO partners, especially just after Kennedy had promised the American people publicly that America would act decisively in case the rumors already in the press concerning nuclear missiles being placed in Cuba were proven to be true. But what would constitute decisive action? At a meeting on the 18th between Kennedy and Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, the Soviets again made the claim that the sites were just for defensive purposes, not knowing that the Americans already knew this to be quite untrue. Thus there was nothing yet to be done diplomatically, as long as the Soviets continued to play this hand of innocence. But still, direct military action? Finally on the 21st, the decision was made to throw a U.S. naval blockade around Cuba, under international law an act of war, but not sufficiently provocative to push Khrushchev to start a nuclear exchange. Further, the next day (the 22nd) the large inter-American alliance of the Organization of American States (an alliance founded in 1948 uniting thirty-five countries of the Western Hemisphere) was called to invoke the terms of the defense treaty, and the OAS gave its support of the "quarantine" idea when the crisis was explained to the organization. This isolated Cuba considerably diplomatically, as well as Soviet Russia, which had long wanted to improve its diplomatic position among the Latin American countries. Also that same day, leaders of America's European allied nations gave their approval to the idea of the blockade. Then that same evening (again, on the 22nd) Kennedy was ready to address the nation on television, explaining the nature of the Cuban missile crisis and the American decision in response to it. The next days were filled with all sorts of talk and speculation back and forth everywhere. It was at this point that the idea of dismantling American Jupiter missiles placed in Turkey in exchange for the dismantling of the Soviet missiles in Cuba was discussed. Turkey was most unhappy at the possibility, even though the missiles located there were, by the technological standards of the day, relatively obsolete – and American nuclear-armed ships positioned in the Eastern Mediterranean were more than able to compensate for the withdrawal of the missiles from Turkey. But for the Turks this was a matter of the appearance of a reduction of American power in support of its ally Turkey. Meanwhile the American naval blockade was put into place, and the first ships headed for Cuba were intercepted – but were allowed to continue onward when it was observed that they were carrying no strategic war materials to Cuba. Nonetheless, the Soviets were not backing down, and development of the launch sites in Cuba continued. And Castro, becoming more certain that an American offensive was about to be undertaken, on the 26th called on Khrushchev to issue a pre-emptive nuclear strike against America, even if only the short-term missiles able to reach no further than Miami were operational at that point. But that would most certainly mean that America would strike back, not only at Cuba (probably destroying the island) but starting an all-out nuclear war with the Soviets. Cuba was not that important to the Soviets however, and on the 27th Khrushchev addressed the world over Radio Moscow announcing a willingness to remove the Soviet missiles from Cuba – if the U.S. did the same with its missiles in Turkey. Castro was furious at this offer, issued by Khrushchev without first consulting with the Cubans themselves. But there was little Castro could do at this point. The game was entirely out of his hands. But it appeared that he was fully ready to see Cuba destroyed, if only it meant that America too (and much of the rest of the world) would be destroyed.5 But this is where Castro and Khrushchev parted company. Then on the same day, an American U-2 plane was shot down, the Russians blaming it on the Cubans (although only the Soviets had the capabilities to do this). At this point the Americans were furious, and warned that if another plane were shot down the U.S. would be compelled to attack all the missile sites (Russian technicians as well as Cubans caught in the attack). Now Khrushchev was beginning to believe that the Americans were truly serious about ending this matter. But then that same day (the 27th) the Kennedy team decided to formally accept Khrushchev’s offer to demobilize the Soviet missiles, not mentioning specifically the Turkish exchange, but quietly implying that this would happen on a "volunteer" basis. On the 28th, Khrushchev, over Radio Moscow, responded in the affirmative to the American offer – however including also mention of the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Turkey. Meanwhile the situation continued unchanged, the Soviets moving ahead in the development of the launch sites, Americans not realizing that over 150 nuclear warheads were present in Cuba, but the American blockade still not backing down. And the Soviets had loaded eight more ships with some 40 missiles and were heading them toward Cuba. But as they approached the America blockade, Khrushchev ordered them to turn around. Everyone breathed a great sigh of relief. The crisis was finally over with the Soviets making the first big move to step out of the crisis Now the Soviets began to dismantle their launch sites in agreement with the Kennedy-Khrushchev accord and in the period November 5th to the 9th, ships carrying Soviet missiles departed Cuba for their return to the Soviet Union. Likewise, Soviet bombers were also removed from Cuba. Thus by November 20th Kennedy announced that the Soviets had fulfilled the terms of the accord, and the blockade was thus being lifted. But what Kennedy and the Americans did not know was that smaller nuclear-armed rockets that had not been detailed in the accord were still in Cuba, and Castro pressed the Soviets hard for authority to use those against America in case of a still-expected American invasion were to occur. This frightened the Soviets sufficiently to have even these removed from Cuba on the 22nd. Also, what the Americans did not know at the time was how very close the world had come to the nuclear exchange which thankfully they now saw being backed down. During the intense days of the crisis, an American ship had dropped depth charges in Cuban waters, nearly taking out a Soviet submarine possessing nuclear missiles of its own, a submarine also possessing orders to use them if attacked, but provided that all three levels of command aboard the submarine agreed. Thankfully one of the three refused to agree to the counter strike, and thus the world was spared the horror of a full nuclear exchange, one that once was started might have spun itself into a global nuclear holocaust! In any case, with the departure of the missiles from Cuba, Kennedy moved to honor the unwritten part of the agreement concerning the missiles in Turkey, and by the spring of the following year (1963) they were all removed from Turkey. In the end it was clear that Khrushchev, not Kennedy, had been the one to back down. This would of course improve Kennedy’s international standing, and help to undercut Khrushchev in his standing within his own party at home in Moscow. In fact, it would be one of the key reasons cited by his fellow party members in demanding Khrushchev’s retirement from Soviet leadership in 1964. 5What

is especially terrifying about this experience is that it makes clear

the fact that such socially suicidal instincts as Castro’s are not

unknown among self-important political leaders willing to bring down

the rest of humanity rather than deal with the failure of their own

leadership (Hitler being clearly a recent example, not to mention

Castro). With nuclear weapons in the hands of such individuals, the

world would find its very survival quite problematic. Hopefully the

world will be able to keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of such

individuals … although in the end only God can offer mankind such

protection.

|

Playing with nuclear-tipped missiles was a very deadly game at this point

Green H-bomb cloud over Honolulu

– July 19, 1962

800 miles to the west another US H-bomb test had been set off (the first one – 500 times more powerful than the A-bomb – was tested in 1952). By this time the Soviets had their own model of the H-bomb. |

Secretary of Defense Robert

McNamara, whose public comments in the spring of 1962

caused the Soviets to fear

that the US might be planning

a pre-emptive nuclear attack

on the Soviet Union

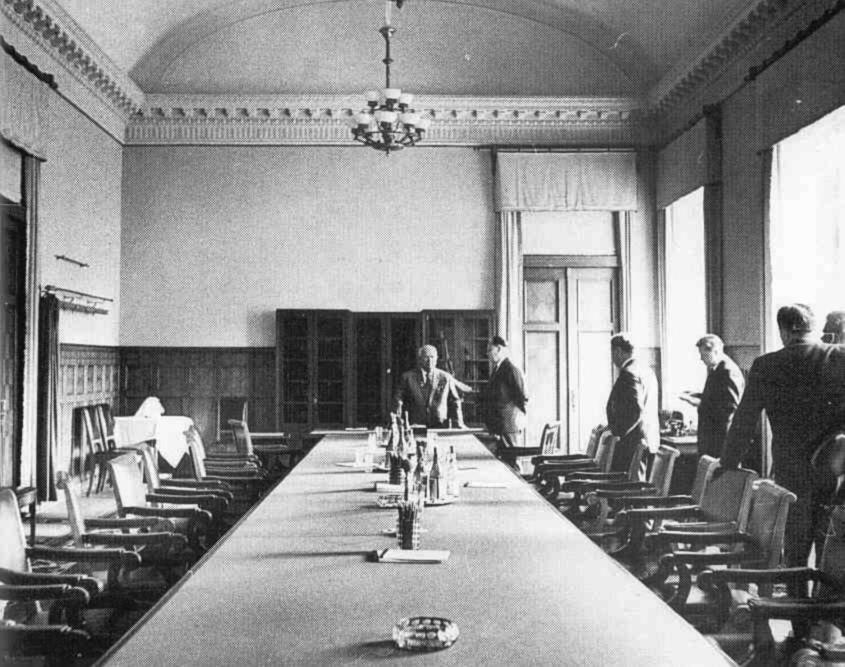

Khrushchev meeting with his

advisers in the Kremlin to discuss the possibility of a US invasion

of

Cuba – and the Soviet Union's deterrent

in the form of nuclear tipped ballistic missiles

placed in Cuba – April

1962

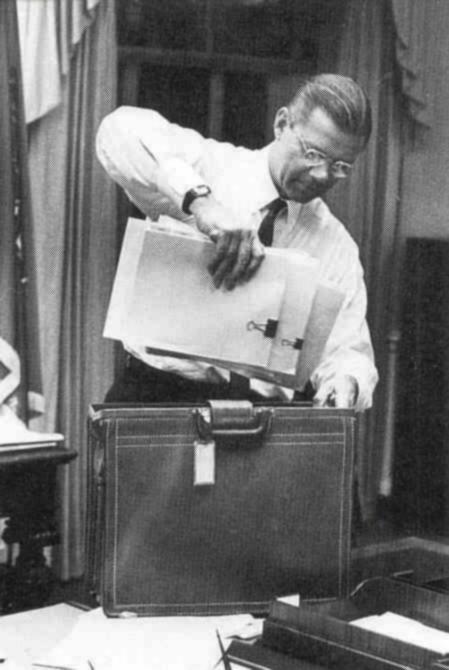

McGeorge Bundy, National

Security Adviser, who informed Kennedy early October 16, 1962,

of the building of Soviet

missile bases in Cuba

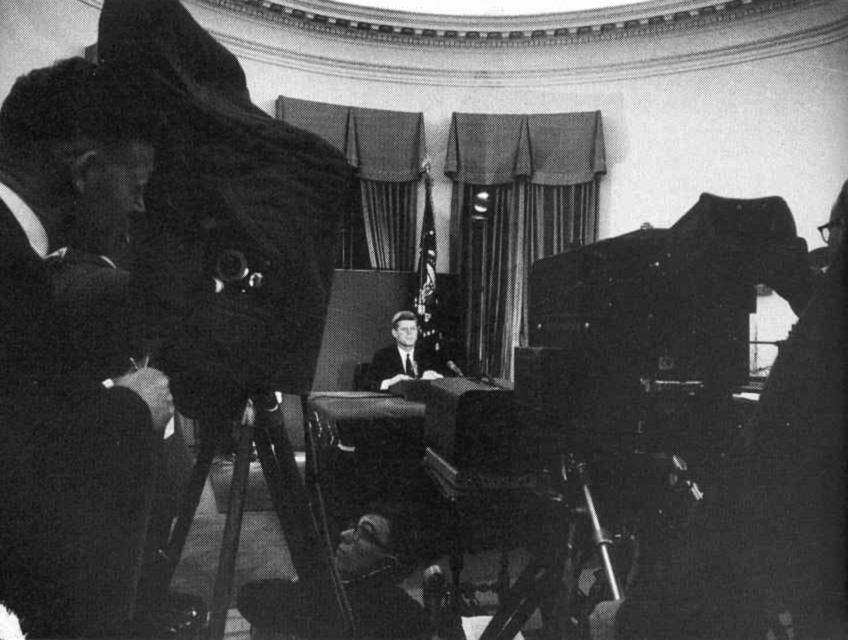

Kennedy's televised announcement

to America about the Cuban missile crisis –

and the proposed American

response – October 22, 1962

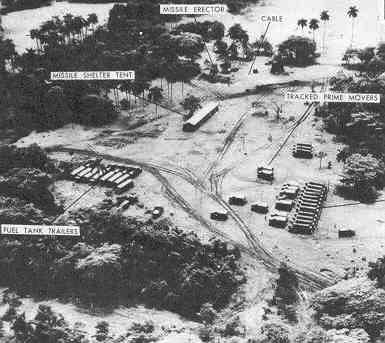

Build-up of Soviet missile

sites in Cuba – 1962

Soviet missile bases in Cuba

– October 15, 1962

An American warship inspecting

the cargo of a Soviet ship near Cuba – 1962

An American warship escorting

a Soviet tanker carrying missiles out of Cuba – summer of 1962

Departure of Soviet missiles

from Cuba

|

The next summer (1963) Kennedy tries

again to stress that his policy

is one of peace for the world – without

surrendering Western freedoms

|

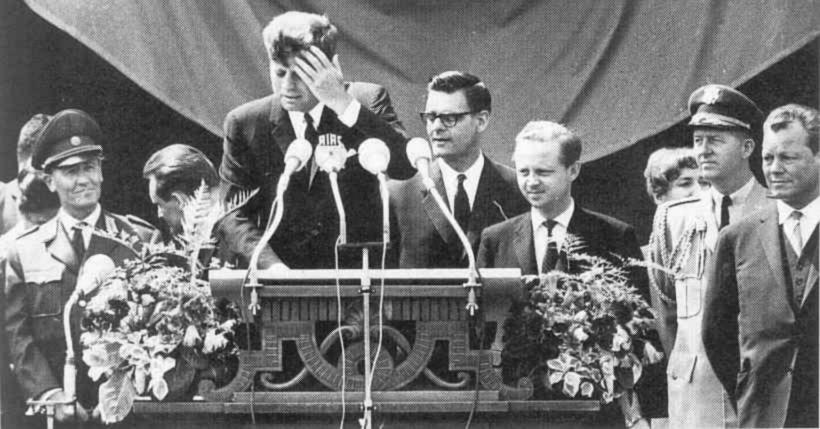

Kennedy revisits the Berlin Wall situation with a personal speech in front of the Wall (June 1963)

Although Kennedy had taken no strong steps to bring down the hated wall that now surrounded Berlin, he decided to make of this affront to mankind a chance to score ideological points against Communism's bullying ways, by coming to Berlin in mid-1963 and making a speech in front of the wall there. Here he uttered the famous (but grammatically somewhat misleading) statement, "Ich bin ein Berliner,"6 as a show of solidarity with the besieged Berliners. Nice, but not impressive, at least not to Soviet Premier Khrushchev. 6What

he should have said was "Ich bin Berliner" (I am Berliner). What he

actually implied when he said that "I am a Berliner" was that he was a

well-known German sweet roll (a "Berliner"). It is sort of like saying

"I am a Hamburger" or "I am a "Frankfurter" (referring to two

well-known foods) rather than "I am Hamburger" or "I am Frankfurter" –

in reference to certain German home-towns! No one is quite

certain as to who it was that advised Kennedy on his German

phrasing! But it certainly was not a German! But the

Germans were gracious enough not to laugh at this very evident mistake

... for they understood the intent of his words.

|

Kennedy at the Berlin Wall

– June 1963

Kennedy delivering his "ich

bin ein Berliner" speech – June 1963

Signing the Test Ban Treaty

in Moscow – August 1963

Nazi leader Adolf Eichman in trial in

Jerusalem for genocide

against the Jews during World War Two – 1961

|

The Middle East becomes a

major scene of Cold War contentions

with the rise of Arab nationalism under

Nasser of Egypt

Arab leader Gamal Abdel Nasser

(Egyptian President)

meets with Communist Foreign Minister Chou En-lai

– 1963

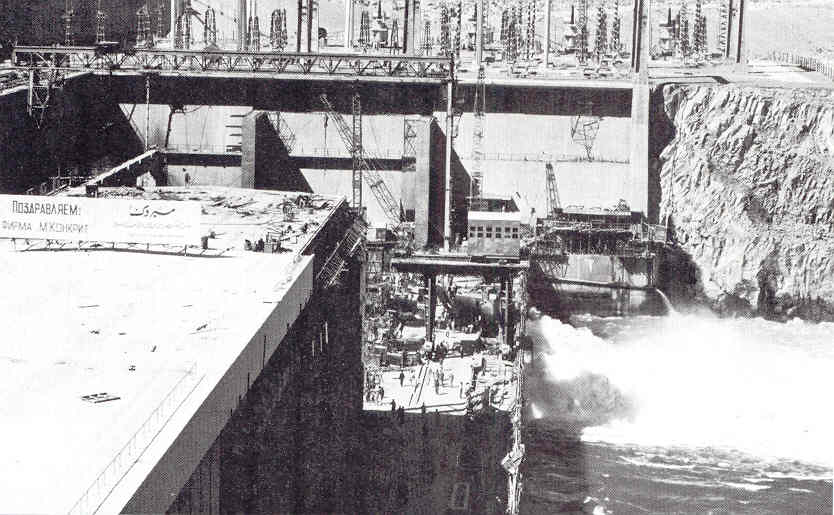

Building the Egyptian Aswan

High Dam (completed in 1971) – with Russian help

|

But the most perplexing problem of all

is the growing threat of communism

in old French Indochina –

At first Laos – but then especially

Vietnam

|

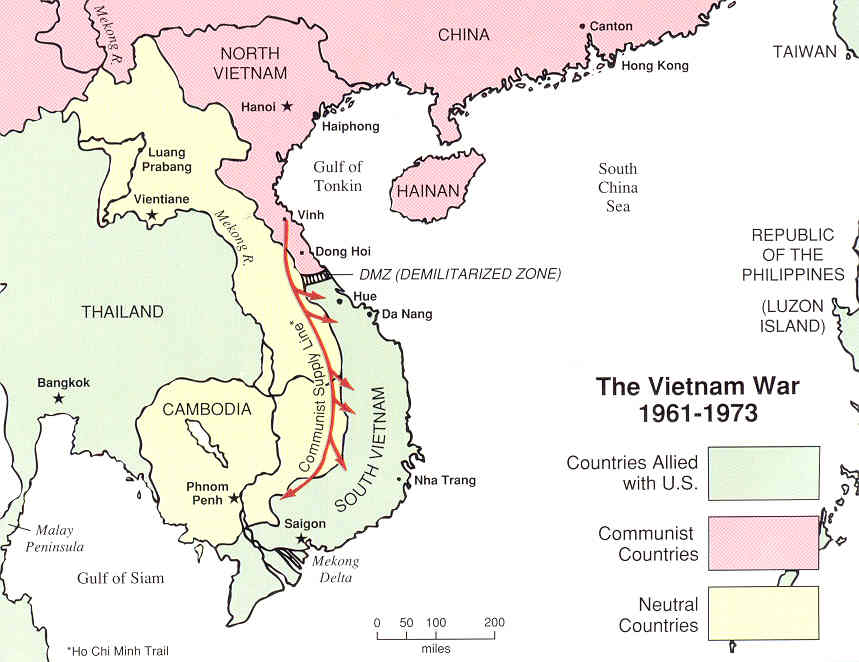

Another major problem seemingly facing the nation was the apparent advance of Communism in the former French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos). Political turmoil had rocked old French Indochina since the collapse of the Japanese Empire in 1945 and the attempts of the French to re-establish their own Southeast Asian empire there. Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam had been a constant scene of strife and civil war among Buddhist peasants and priests, French-speaking Catholic townsmen, Communist intellectuals, nationalist guerrilla leaders, and various minority groups scattered throughout the region. France had finally given up its effort to hold the area and had withdrawn in 1954-1955. Gradually, with the Communism which had overtaken China seeming now to be gaining momentum in the Indochina region, and with France dropping out as the defender there of a pro-Western status quo, America found itself drawn to the area as the new protector of that same status quo. Kennedy was cautious about making a huge American commitment to the area. He sent military advisors or trainers to help the Westernized elite in Laos and South Vietnam defend their land against the Communist soldiers and guerrillas. But this effort did not seem to be keeping up with the worsening of the crisis in Southeast Asia, notably Laos, and then Vietnam (and to a lesser extent Cambodia). Efforts to negotiate a compromise seemed not to slow the progress of Communism in the region. One (of several) of Kennedy’s big concerns about Southeast Asia was the government of the South Vietnamese strongman Ngo Dinh Diem, who had actually been put in place in the 1950s by the Americans themselves. His style (because it was authoritarian – or just because it was highly pro-Catholic?) was clearly irritating the very people in Vietnam (heavily Buddhist) that Americans were trying to save from Communism. Kennedy interpreted the situation as America needing to be more truly supportive of the democratic process, which Diem hardly symbolized. Thus Kennedy helped to plan the military overthrow of Diem, hoping idealistically that Diem’s removal would enable a more "democratic" (and thus supposedly more pro-American) government to come to power in South Vietnam. That Kennedy would think that a new government more committed to Western democracy should satisfy the Buddhists (one of them burning himself in public protest in June of 1963), whose argument was cultural rather than political, was typical of the national naďveté that afflicted (and still afflicts) America, even the sophisticated Kennedy. Actually, the attempt at removing Diem led all the way to his (and his brother’s) assassination at the beginning of November, 1963 – only making the now leaderless South Vietnamese situation much, much worse. But Kennedy himself was soon assassinated (merely three weeks later) before anyone could see what Kennedy planned to do next to get things settled back down in chaotic post-Diem Vietnam.

|

A Buddhist monk, Thich Quang

Duc sets himself on fire in protest against Diem's

Western cultural

assault on Vietnamese Buddhist traditionalism – June 11, 1963

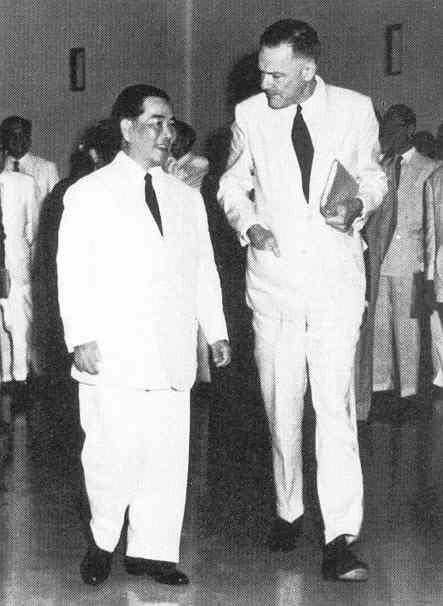

US Ambassador Henry Cabot

Lodge visiting South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem

– October 1963 (while encouraging the military

coup that would assassinate Diem in November)

The bloodied body of South

Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem

The military coup started on November

1st. Diem and his brother were killed on the 2nd

... supposedly "opening the door for democracy" in

South Vietnam.

But only chaos resulted. South Vietnam would never again

acquire a stabilizing government.

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges