|

Johnson grew up on a farm in the tiny and

rather remote community of Stonewall, Texas, in a condition of constant

poverty and humble social circumstances, although his family had a

somewhat impressive history dating back to the early days of Texas. In

fact, the nearest town in the region, Johnson City, was named after one

of his relatives. The young Lyndon attended high school in Johnson

City, and eventually entered Southwest Texas State Teachers College in

San Marcos, where he developed a taste for politics and ended up as

editor of the school newspaper. He took time off during his studies to

teach a full school-year to Hispanic-American children, which touched

deeply an old nerve in Johnson, one that never failed to make him

greatly concerned about the problems that people face living in utter

poverty – something he personally could identify with closely.

Graduating in 1930, he found a position

teaching high school public speaking in Houston and also got involved

in Richard Kleberg's Congressional campaign. With Kleberg's victory in

late 1931, Johnson followed him to Washington, D.C., where he found

himself by natural impulse organizing Congressional aides into

something of a political fellowship. Eventually that fellowship would

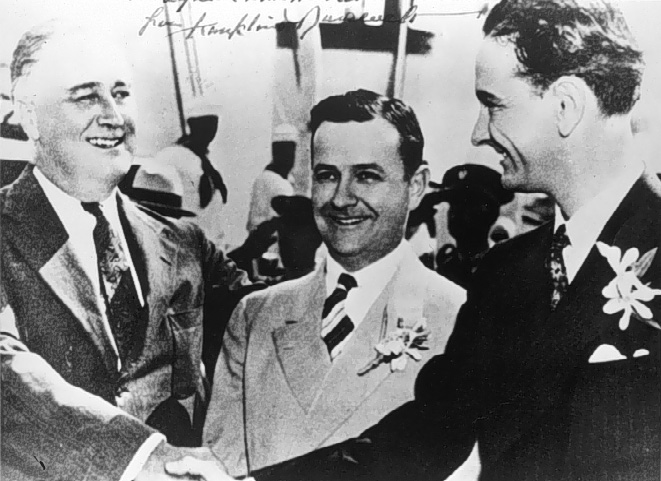

include staff members of newly elected President Roosevelt. But it

would also grow to include even a direct friendship with Vice President

John Nance Garner and powerful Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, both

Texans. In fact, Johnson's relationship with Rayburn would grow over

the years, forming a strong political bond between the two.

In 1934 he married Claudia ("Lady Bird")

Taylor of Texas, whose mother (of aristocratic Alabama ancestry) died

when Ladybird was only five. Her father was a strong-willed Alabama

sharecropper who managed to move to Texas and put together a fortune,

coming to own 15,000 acres of cotton and two general stores. Growing

up, Lady Bird ventured back and forth between Texas and Alabama, but

eventually attended and graduated from the University of Texas, and

then headed on to Washington, D.C., where she met Johnson, marrying him

only ten weeks later.

In 1935 he returned to Texas to became

head of the Texas National Youth Administration, a big part of

Roosevelt's New Deal, given the task of setting up government-sponsored

jobs and job-training for unemployed Texas youth. This was a key

component of Johnson's understanding of the proper role of government,

one that would stay with him during the years ahead as he entered more

fully into political life.

In 1937, financed heavily by his wife, a very ambitious Johnson ran

successfully in a special Congressional election, and would continue to

serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during the next dozen years,

most importantly during World War Two, proving to be a key supporter of

Roosevelt's legislative agenda. He joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in

1940, was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander, and when America

entered the war in December of 1941, he was called to active duty. He

wanted a combat appointment but instead was put to use by Roosevelt

during the early part of the war as an investigator into general

conditions of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, this leading him eventually

to be a chairman of a key subcommittee of the House Naval Affairs

Committee investigating navy contracts with America's manufacturers

(similar to Truman's role in the Senate investigating army contracts

during the same period).

After the war, in the 1948 national

election, Johnson ran for a U.S. Senate seat, gaining (very narrowly,

and very questionably) the Democratic Party nomination, and thus in the

Dixiecrat South (which included Texas) most assuredly the subsequent

election itself (Southerners at that time were still refusing to vote

Republicans to any office). Now in the Senate, Johnson was quick to

befriend the powerful Senator Richard Russell and also help create and

then lead a Senate subcommittee investigating government contracts with

the defense industry, very similar to the role he played in the House

of Representatives.

By 1951 he had gained the key position of

Senate Democratic Party Majority Whip. Then when in the 1952 elections

(which brought Eisenhower to the White House) the Republicans swept the

Democrats out of power in both houses of Congress, in the new Senate

political reshuffle in early 1953 Johnson was elected by fellow

Democrats as the new minority party leader. This made him the youngest

person ever to be elected to that powerful position (he was only

forty-four at the time). Then when in the 1954 elections the Democratic

Party regained the majority in the Senate, Johnson became the majority

party leader. This would make him not only one of the youngest but also

one of the most powerful leaders in Washington, D.C.

Johnson grew up in a family that had a

number of Baptist pastors in its recent genealogy on his mother's side

of the family, whereas his father had merely a distant relationship

with the world of religion, only occasionally attending the Disciples of

Christ (DOC, or just "Christian") Church in Johnson City. But it was in

this church that Johnson would grow up, a rather different sort of

denomination than the Southern Baptists and Methodists of the

camp-revival variety that dominated the local religious scene. The DOC

had been founded in the 1800s in an effort to create a Christian form

that adhered to no particular doctrinal or liturgical structure. And

this seemingly left its mark on Johnson, who in later years (really

only after he became president in late 1963) would find himself

comfortable in any of America's Christian denominations, even Catholic.

And he especially loved to find himself in the company of pastors, of

any variety. But actually, Johnson seemed to develop a preference for

the more liturgical (Catholic and Episcopalian) churches to attend,

although ultimately he could be wide-ranging in his choice of where he

would worship on any particular Sunday, sometimes even attending more

than one church on that same morning. Part of this was that he truly

felt at home within the broader spectrum of Christianity. But he also

liked to be out in the crowds (always hating to be alone). Of course

this never hurt his political status either. Also it kept him one step

ahead of the press, who naturally wanted the week's latest story on

where Johnson had attended church (he loved to keep the press guessing).

But clearly the one person who meant the

most to the president in the religion category was the evangelist Billy

Graham (whose contact with President Kennedy had been quite minimal).

Graham and Johnson became very close over the years of the Johnson

presidency. Graham was called on to speak at every one of the

presidential prayer breakfasts in those years, and Graham met

frequently with the president both in the White House and on Johnson's

Texas farm, to pray and offer comfort to a personal friend who was well

aware of the troubles his presidency had come to encounter. Johnson

even asked him in 1964 as to who he thought would make the best running

mate, to which Graham wisely declined to give an answer! Graham stayed

with Johnson the president's last night at the White House, and

eventually would be called on to conduct Johnson's funeral service

(1973). But very little of this close relationship was known outside

the inner Johnson social-political circle.

Johnson never saw the need to personally

inspire, through his own spiritual qualities, a "Christian America." He

did not usually talk about his religion publicly, or bring religion

into his public arena. Although he himself personally was a fairly

strong Christian, and found himself in personal prayer often over his

work, his public working-world was strictly Secular, and would remain

that way, even through all the difficulties he would face in trying to

lead the nation.

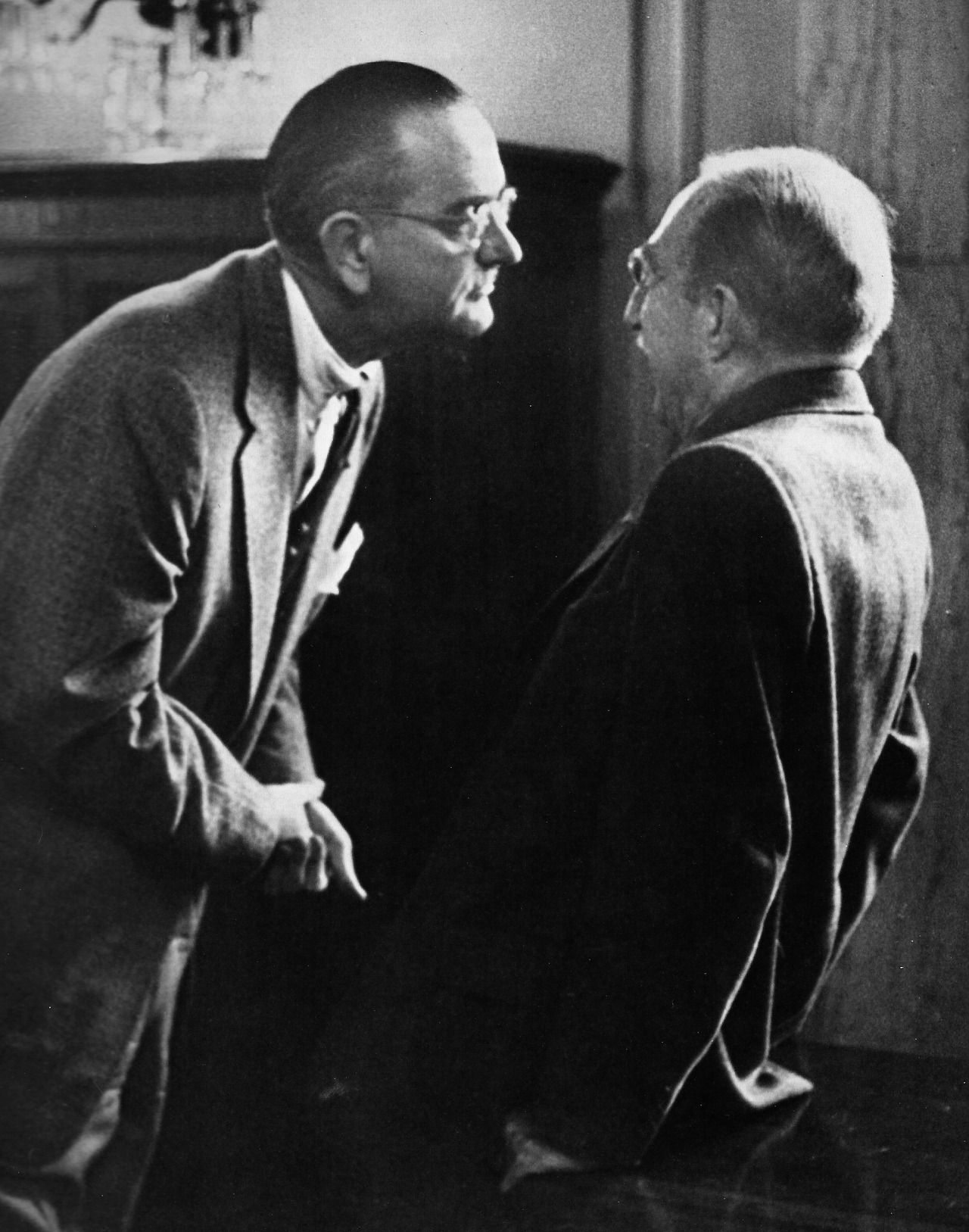

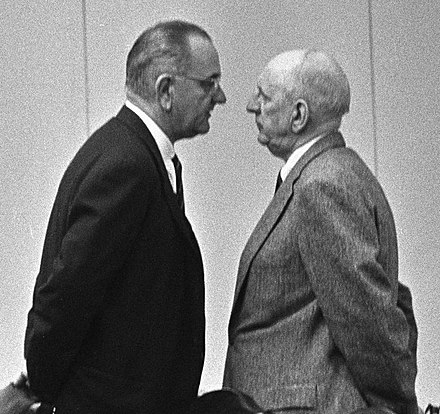

Johnson carefully researched every person

he would have to work with in Washington, finding their strengths and

weaknesses, their positions on various issues. Indeed, he was

well-known for his ability to go to work on his political colleagues,

towering over them hugely (he was a big man) in personal face-to-face

discussions, literally so, only an inch or two separating his face from

theirs as he pressed his views upon his intimidated victims.

He was very sensitive to the blemish of

poverty still afflicting the supposedly prosperous nation. Very

importantly in how he viewed this issue, he had come into the world of

politics as a young man deeply committed to Roosevelt's New Deal

program, and had a strongly ingrained sense that the government in

Washington was the best source of solid political, economic and social

reform for the nation – despite whatever the Constitution had to say on

these matters.

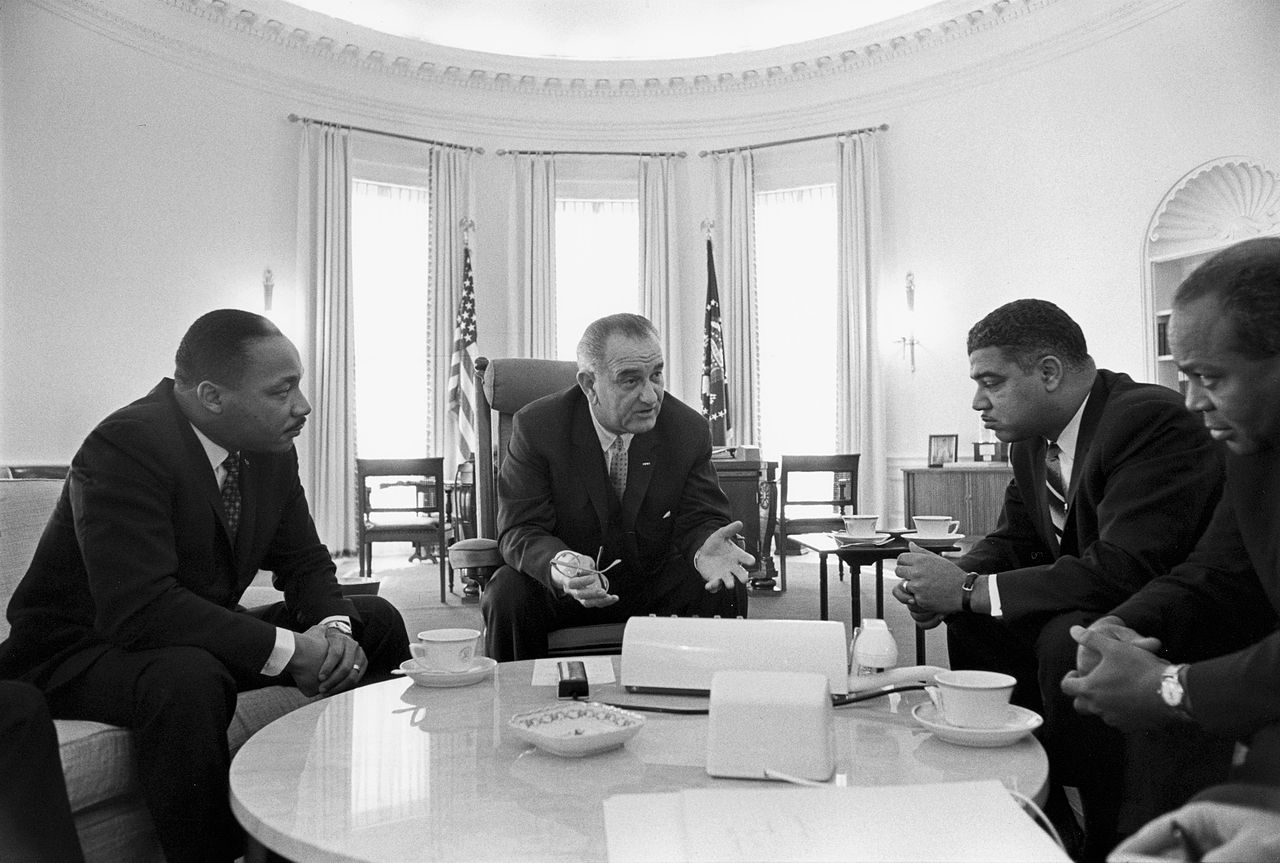

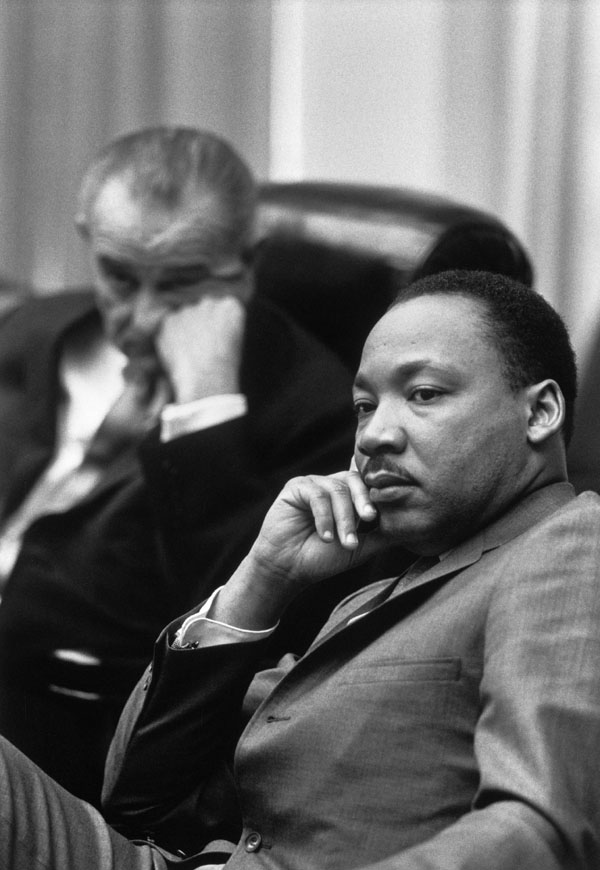

Also, as a Southerner, personally stung

by the way fellow Southerners had dug in their heels against Black

civil rights, he was by no means convinced that a mere appeal to the

American conscience was sufficient to get Americans to do the right

thing. Thus to Johnson it seemed to make more sense to him, on a number

of different political fronts, that real reform had to come to America

by way of a strong central authority, namely the Washington government

that Johnson had come to know quite well.

Besides, he was well-aware of the fact

that he lacked the personal qualities that could charm the American

people to action like Kennedy. He did not have a charismatic

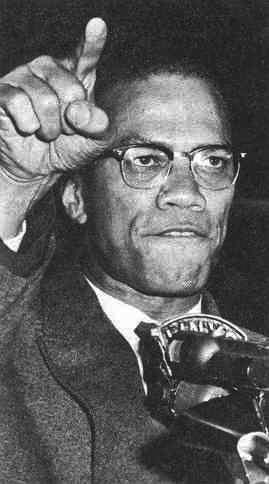

personality that could move the public like King. No, he was a

behind-the-scenes political maneuverer – a very effective one at that.

He could get things done in Washington that not even a Kennedy or a

King could achieve, because of the huge amount of personal political

leverage he had developed in dealing with the other members of Congress

as Senate minority and then majority leader.

Johnson was also one very impressed with

professional credentials, ones that distinguished the experts of

Washington's powerful political circles from the common folk back home.

He was very definitely a deeply committed "Washington insider," as few

U.S. presidents before him had been.

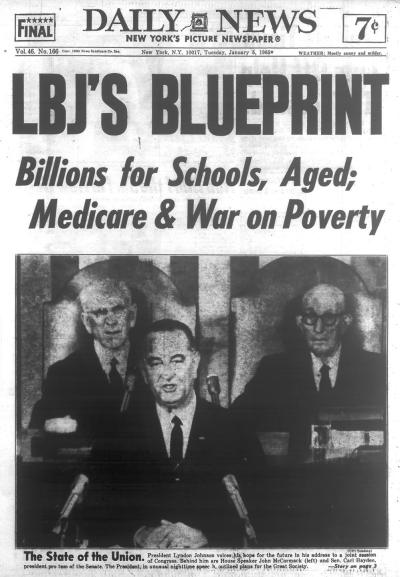

Thus he would eventually come to put

forward his Great Society idea, a set of government programs run out of

Washington by political professionals, which he felt was the most

effective way to bring America to perfection. To Johnson's way of

thinking, professional economists, public administrators, lawyers,

etc., brought to Washington to engage in their professional work and

duties, seemed by far to be the best way to get the job done of

perfecting America.

So it was that Johnson pursued American

politics not along the lines of great idealistic challenges to equally

idealistic (and socially self-motivated) Americans, as Kennedy had, but

more in terms of an aggressive out of sight herding forward of the

Washington congressional and executive bureaucratic machinery. He

relentlessly pushed forward his political program of social reforms

through this Washington political machine – expanding it to rather

colossal proportions in the process.

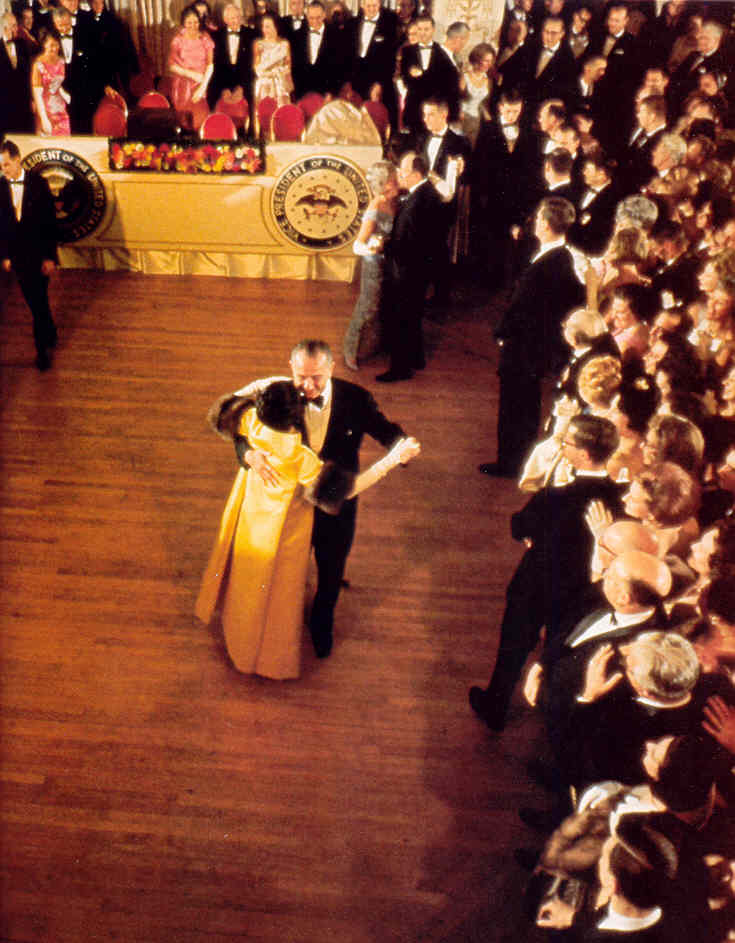

Under Johnson, Washington D.C. transformed itself into a great imperial

metropolis – also improved greatly in appearance through his wife Lady

Bird's huge efforts to make the capital appear indeed to be just such

an imperial metropolis.

|

The

American presidency under Johnson ... not quite Camelot!

The

American presidency under Johnson ... not quite Camelot!

The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ)

The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) The

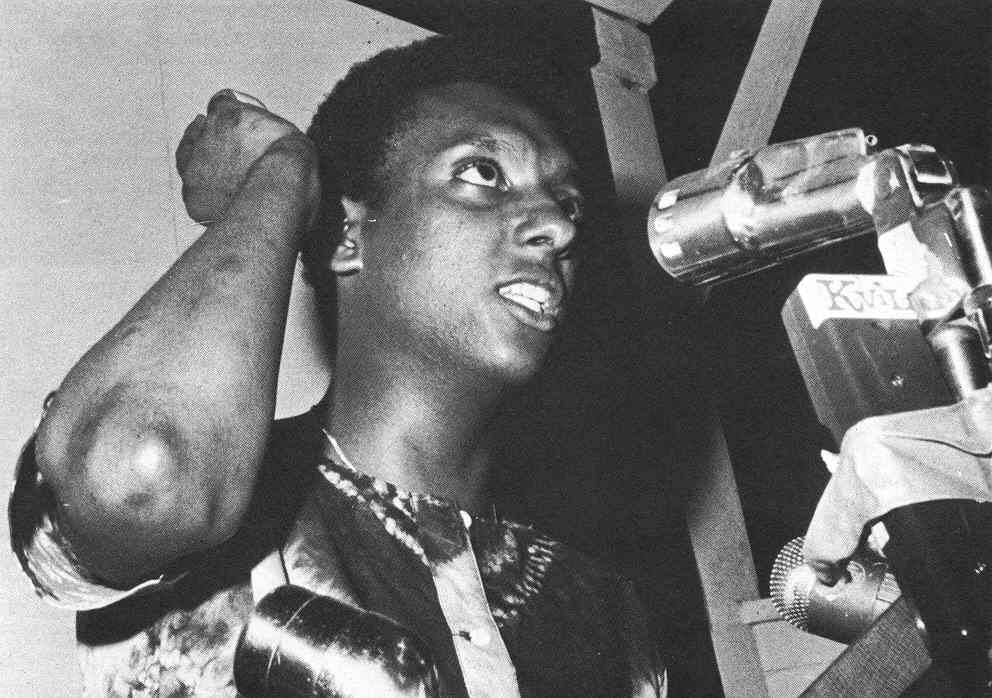

civil rights movement gains steam

The

civil rights movement gains steam Johnson's "Great Society" program – May 1964

Johnson's "Great Society" program – May 1964

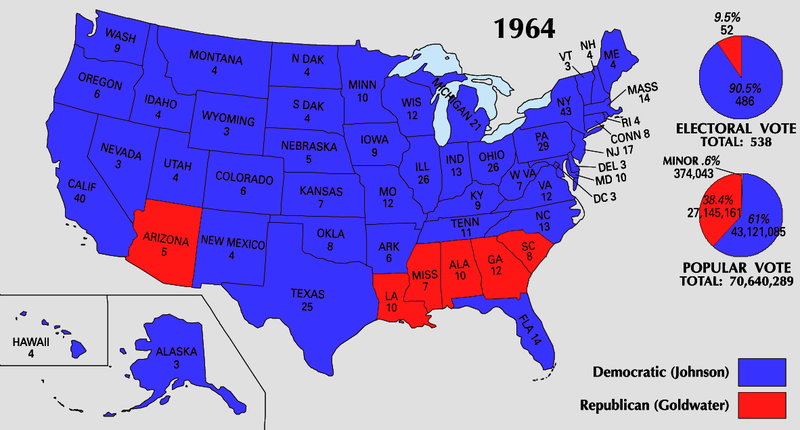

American politics takes a left turn under Johnson

American politics takes a left turn under Johnson The continuing attempt to protect religion fromSecular-Judicial regulation

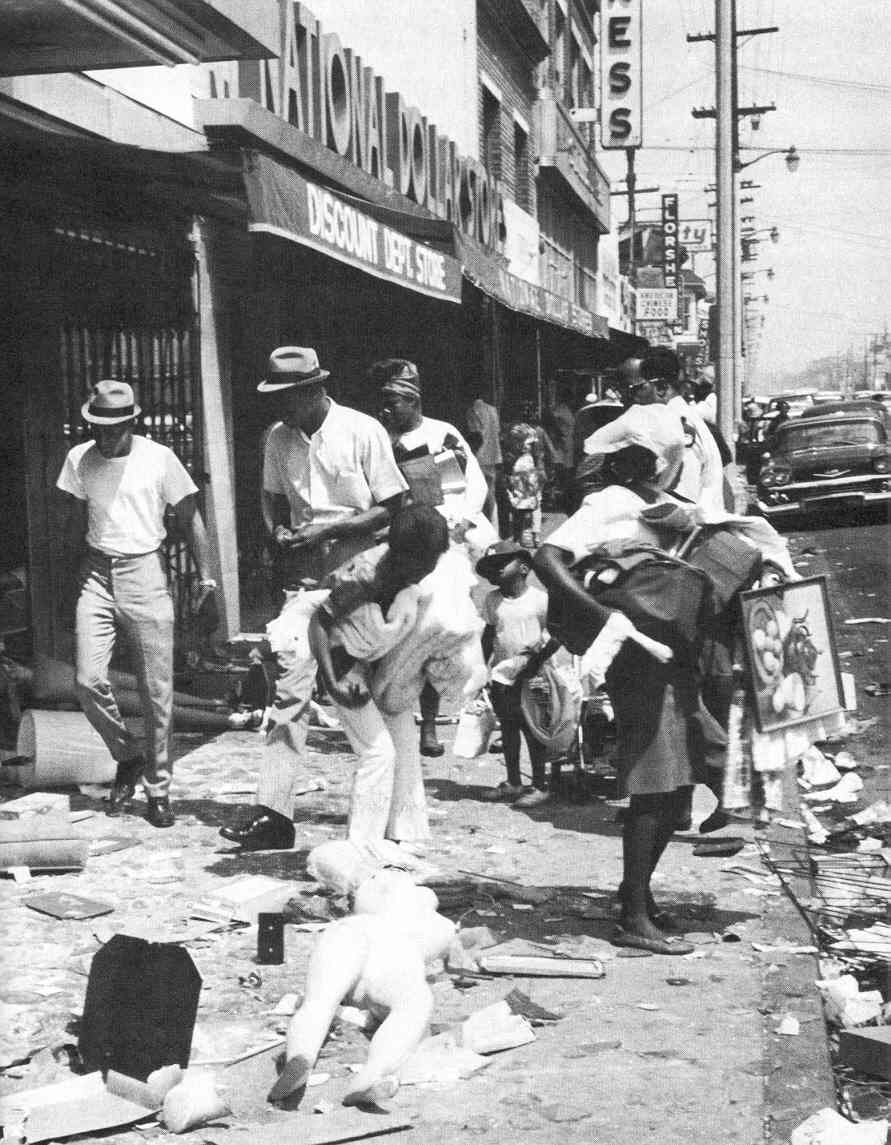

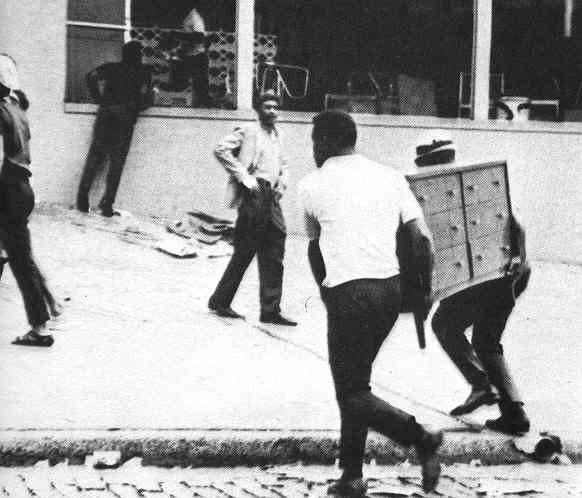

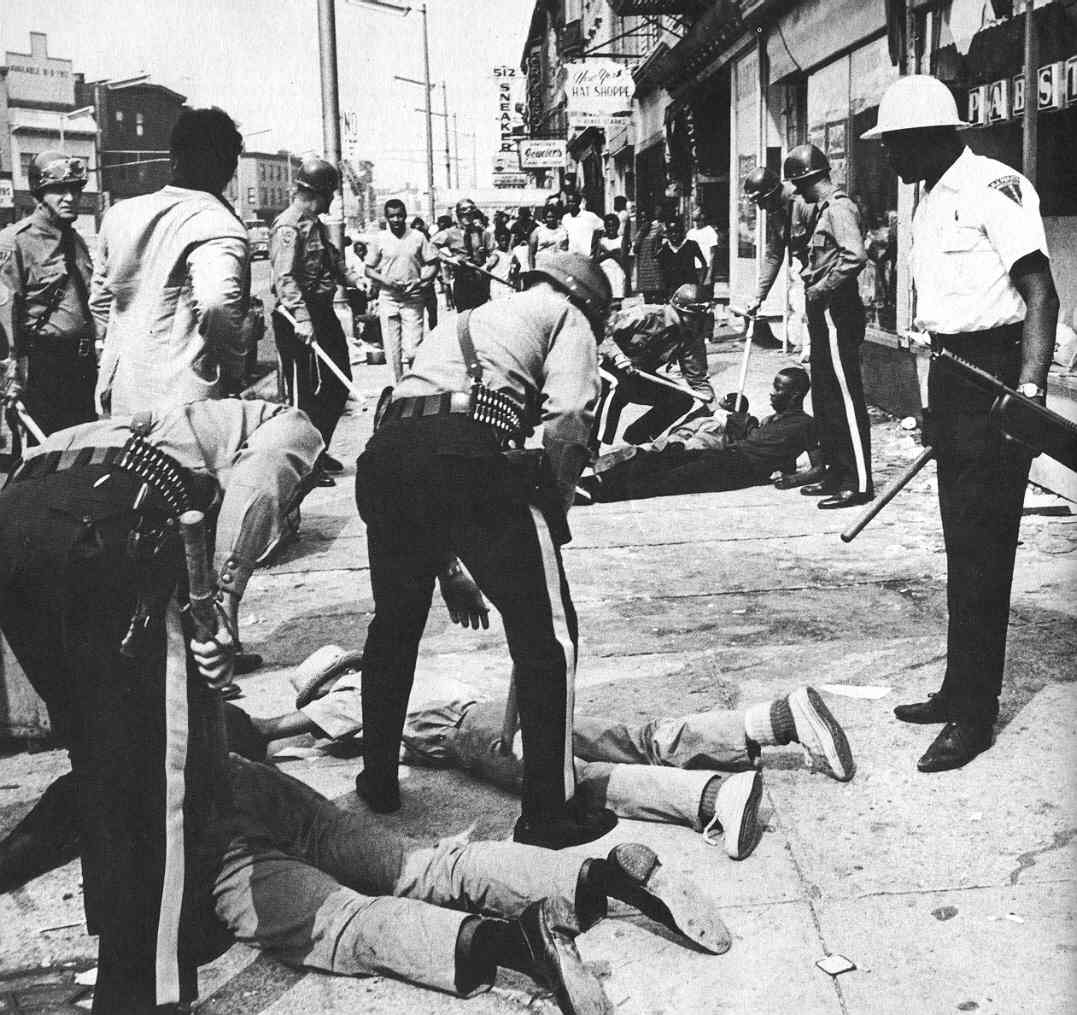

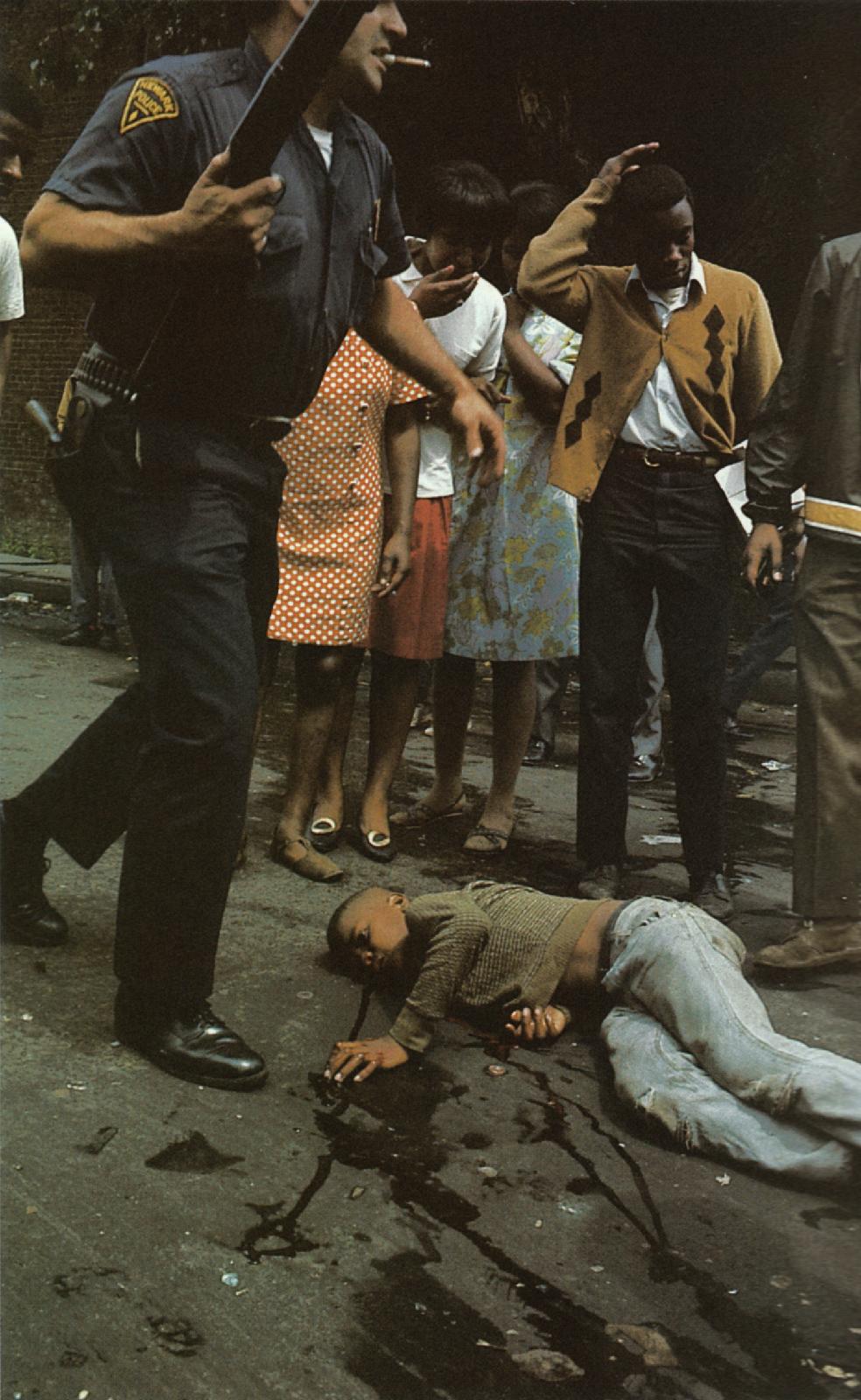

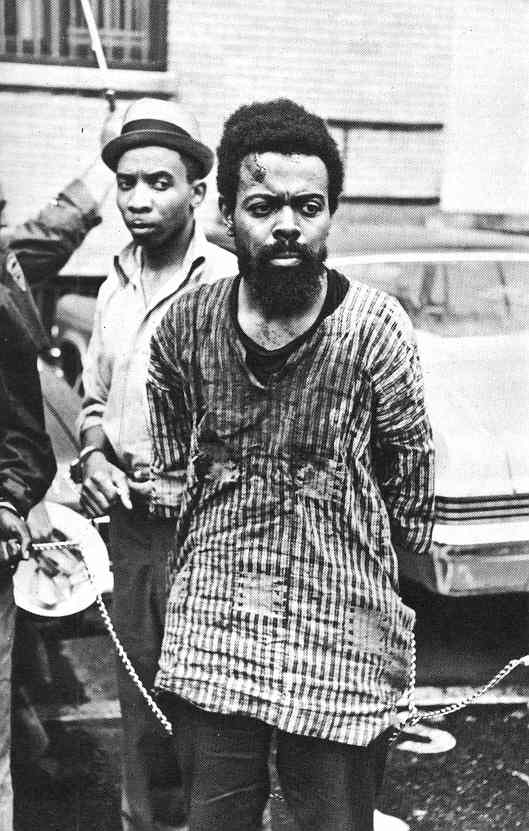

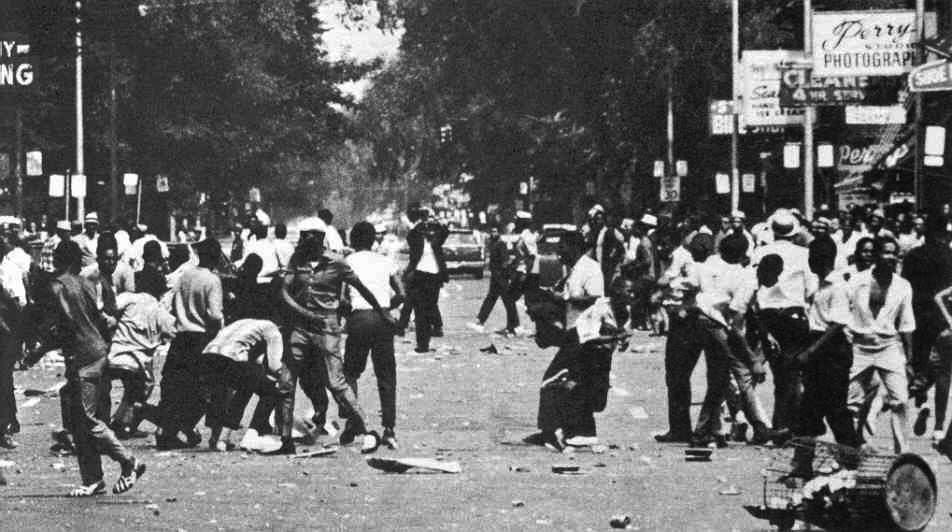

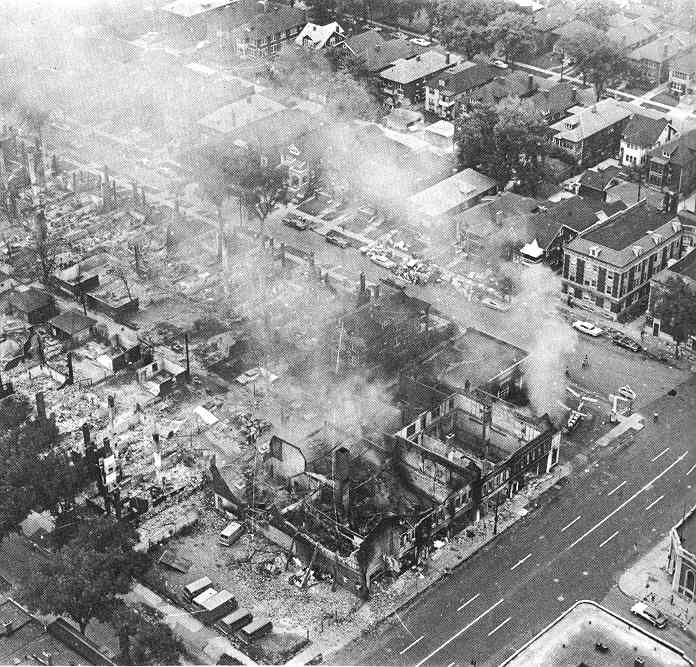

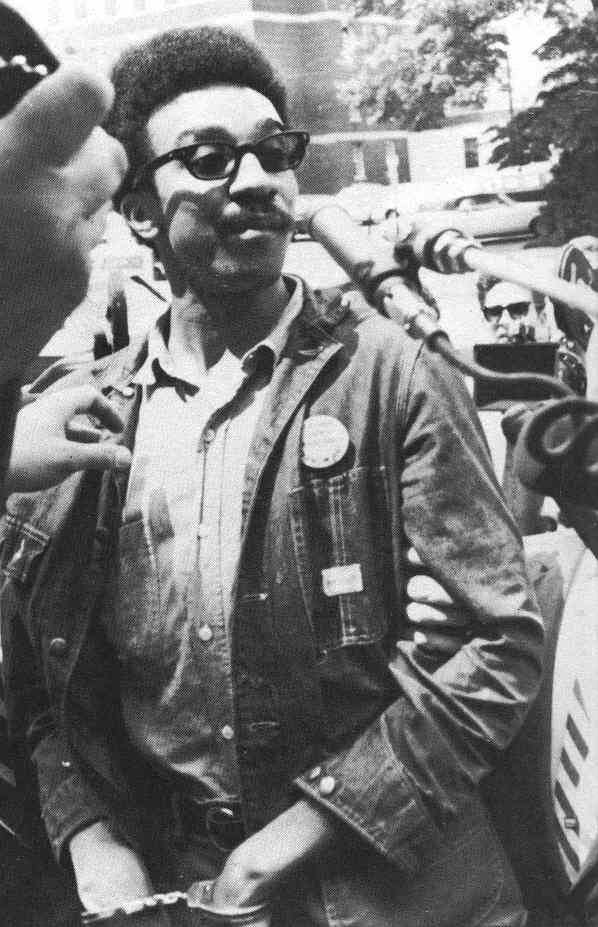

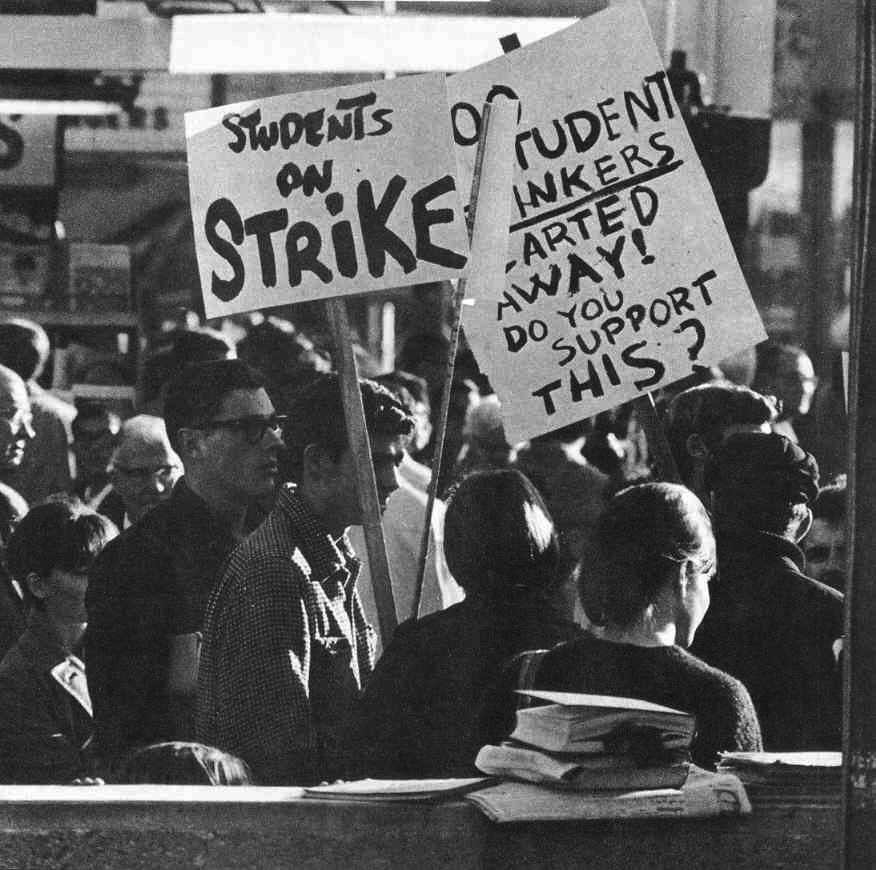

The continuing attempt to protect religion fromSecular-Judicial regulation Race relations worsen

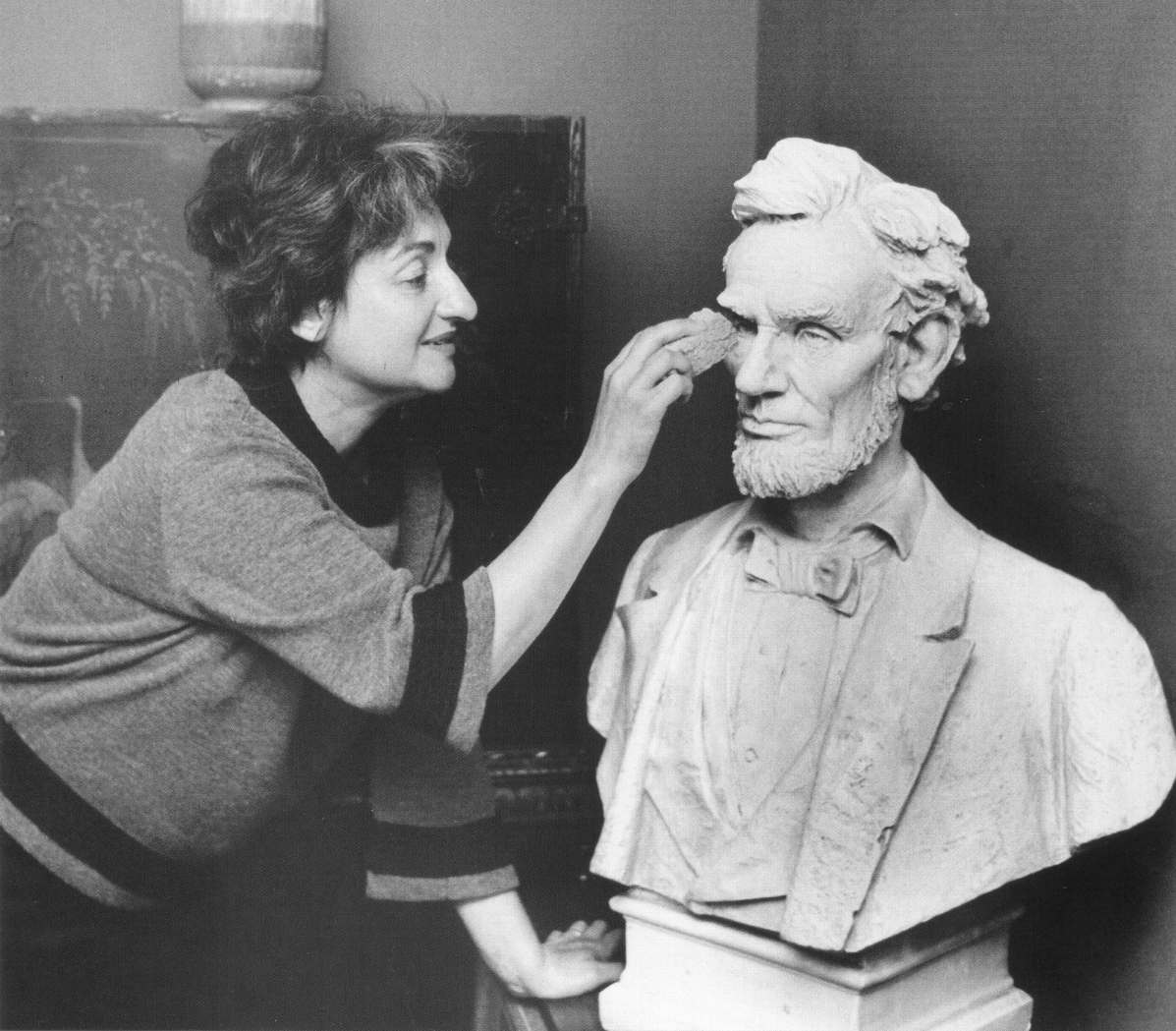

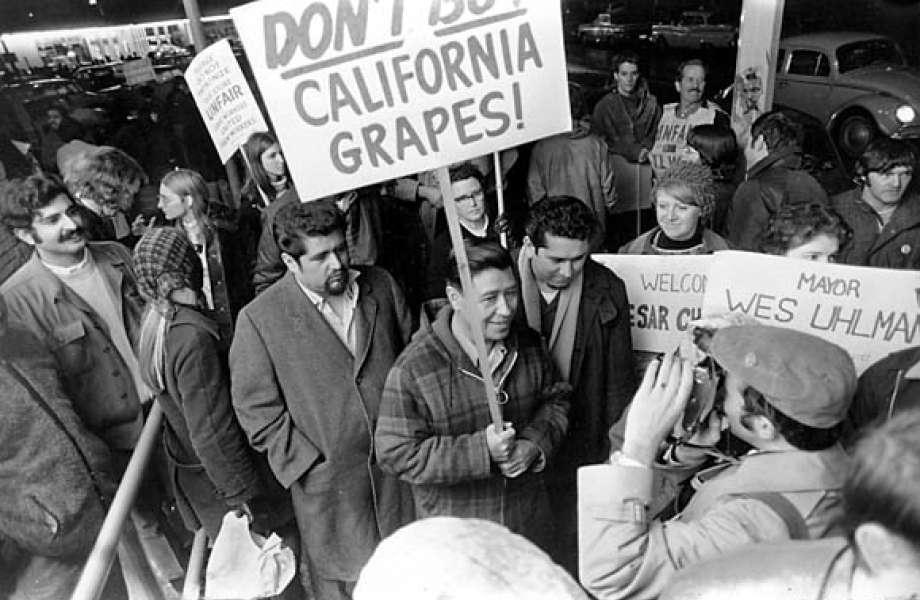

Race relations worsen Affirmative action also for women and Hispanics as suffering "minorities"

Affirmative action also for women and Hispanics as suffering "minorities" The growth of the Federal state ... and the Federal debt

The growth of the Federal state ... and the Federal debt

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges