Political

Realism would have had no difficulty in finding acceptance from either

the Founding Puritan Fathers or the Founding Fathers of the American

Republic, for it is a political philosophy that arises from the basic

premise that man instinctively engages the world around him most

powerfully on the basis of what he understands "logically" as his own

(sinful) self-interest.

Political Realism is aware that man is a moral animal, in the sense

that he feels compelled to justify his actions on the basis of some

moral logic or moralizing of his own. But even this moralizing is

simply another aspect of his pursuit of self-interest. Morality is

simply the way a person logically justifies his pursuit of

self-interest, to others – even to himself.

For instance, a Realist realizes that moralizing is simply a verbal

cover the individual offers up in the hope of presenting a compelling

reason for others to yield to that individual's set of interests (such

as a lawyer before a jury, or a six-year old before a scolding parent).

It may actually include a lot of lying or slick deception in the hope

that such deceptive moralizing will shape more advantageously the

behavior of others.

A Realist, in attempting to deal with others, however, must first be

clear in his own mind about what, in any given situation, his

self-interests truly are. He must be very careful not to confuse his

own moralizing with his true self-interest, which is fairly easy to do,

and which in fact is often done in history, usually with disastrous

results (say for instance when Hitler himself truly began to believe

the lie he put over on the rest of the German nation that he was a

diplomatic and military genius).

It is also very important that the Realist try to understand the actual

self-interest behind the moralizing of the others around him. He should

study life's challenges from their perspective, to try to understand

how it is that others see things, and thus how they are likely to act

in any particular situation on the basis of what they think they see. A

Realist should also pay close attention to the moral arguments he hears

from others, not to sit in judgment as to whether they are objectively

right or wrong but because they give him a better insight into how

others perceive their own self-interest.

This is an important contributor to the Realist's ability to understand

and anticipate the behavior of others, and to his ability to respond to

the logic that others will use to give moral cover to their behavior.

The Realist also understands that self-interest is shaped tremendously

by power. Power is the amount of ability a person has to actually

pursue his sense of self- interest. The more power a person has, the

more a person's sense of self-interest will expand. Little power

enables only the most-humble pursuit of self-interest. Great power

enables a wide ranging, domineering pursuit of self-interest.

But of course, power is a rather limited factor. No one, no nation, has

total power. Everyone, every nation, has some power, and needs to know

exactly how much that actually is.

Power in a social context is not a particular material quality, but is

simply how strengths in oneself and in others are perceived. Power is

highly symbolic in nature. Certainly there are material attributes that

shape that perception: guns, bombs, size of armies, size of the

industrial infrastructure, size and training of the population itself.

But of equal and usually even of greater importance are such

intangibles as a reputation for power, wisdom (or lack thereof), a

sense of optimism (or conversely, pessimism), and simply bravery or an

inner strength willing to take on risks. This latter element of power,

bravery, is where a deep faith in or sense of higher connection with

the One who controls all life becomes absolutely essential (although

this idea does not play as central a role in classic Realism as it

should, though most Realists do recognize the connection).

Modern Political Realism is ultimately about nations, their interests

(the "national interest") and their power. A nation must have a very

keen sense of its own national interest, as well as the national

interests of the other nations playing at the "game board" of world

diplomacy. A nation must also be very aware of the size and nature of its

own power, material and symbolic, as well as the power of others. In

short, it (or at least its leaders) must know how to size up both

itself and others.

Before a nation ventures into a new move on the game board it should do

a very thorough cost-benefit analysis of the situation. How important

is this particular move? What are the gains or benefits that will

probably come from this move? How much is it going to cost the nation

to make this move? How much of its limited resource of power is it

going to take to put national muscle behind this move?

Failure to get this analysis right (or worse, failure to undertake this

cost-benefit analysis altogether, which sadly is often what happens,

especially to Idealistic America) can bring disaster, even total ruin

to a nation. For instance, nations that exhaust themselves in a war

that brings no offsetting gain have simply squandered needlessly, even

foolishly, even tragically, their power. In doing this they have left themselves

vulnerable to the aggressions of a nation of growing power that is

willing to test the weakened nation to see how badly that nation got

depleted by its political folly. Political nature will simply take out

that nation that has self-inflicted wounds wrought through folly.

A wise nation moves cautiously in the international diplomatic/

military game. It attempts to join forces with other nations who are

pursuing similar national interests in order to combine forces and not

expend drastically its own power. Sometimes it has to ally with others

simply because it does not have enough power to take on a challenge by

itself. This is how Roosevelt's America and Churchill's Britain found

themselves in alliance with Stalin's Communist Russia during World War

Two (1939-1945). Germany was so powerful that it necessitated this

alliance to bring Germany to defeat. They allied not because they

shared similar moral codes and political cultures (although of course

Britain and America certainly did). It was simply that as long as

Germany was running loose across Europe, they all shared a common

national interest of defeating Germany. Period. But once Germany was

defeated, that alliance broke down (the Cold War took its place),

because principally America (with Britain in support) no longer shared

a common interest with Russia. In fact at that point their national

interests were in something of a natural conflict over Europe, and then

soon over the entire world, as they were bound to be (as both Truman

and Churchill were quick to understand after the war's end in 1945).

As odd as this may sound, self-interest can lead to some of the most

charitable acts in the world of diplomacy and international relations.

For instance, after World War Two, Truman and his America expected

Europe to simply put itself back together after the shooting stopped.

But within two years the Europeans had exhausted what was left of their

social assets in the effort to rebuild. Politically as well as

economically they were bankrupt. Stalin saw great advantage to his

Soviet Union in this situation and called on his Communist allies in

the West to thoroughly disrupt what was left of the social order in the

West – to give him, through his Stalinist agents, full control of

Western society. Truman (and his Secretary of State George Marshall)

immediately understood the danger this put not only Europe but also

America in ... and moved to offer Europeans full economic assistance in

rebuilding their societies. The offer was extended even to the Russians

if they had wanted it – which of course would have been totally

contrary to Stalin's Soviet self-interest, and therefore was refused in

the East. But the "Marshall Plan" did the trick, settling things down

both economically and politically in Western Europe. But it also gave

America the task of using its factories and farms (and thus jobs for

Americans as well) to supply much of Europe's needs for rebuilding. And

both societies prospered enormously in the process! That was true charity – formulated out of a strong

sense of political self-interest on the part of everyone (except

Stalin)! That's also political Realism in action – in the very best of

ways!

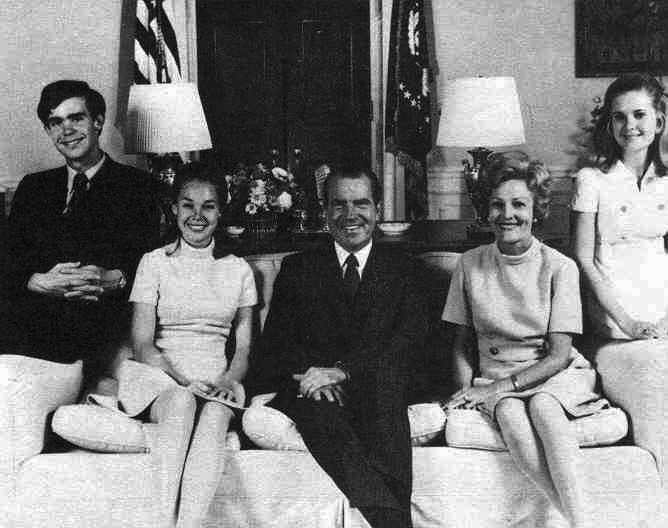

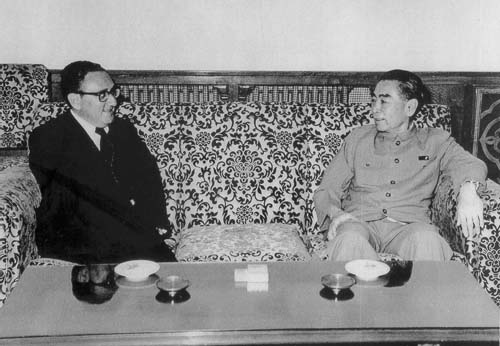

Nixon and Realpolitik (Political Realism)

Nixon and Realpolitik (Political Realism)

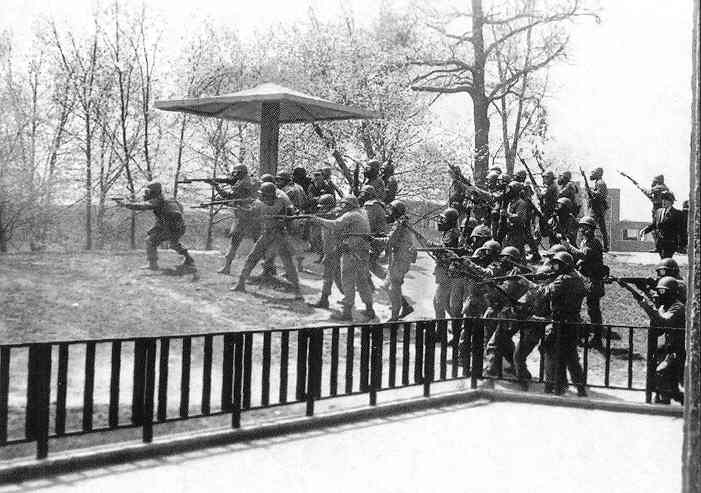

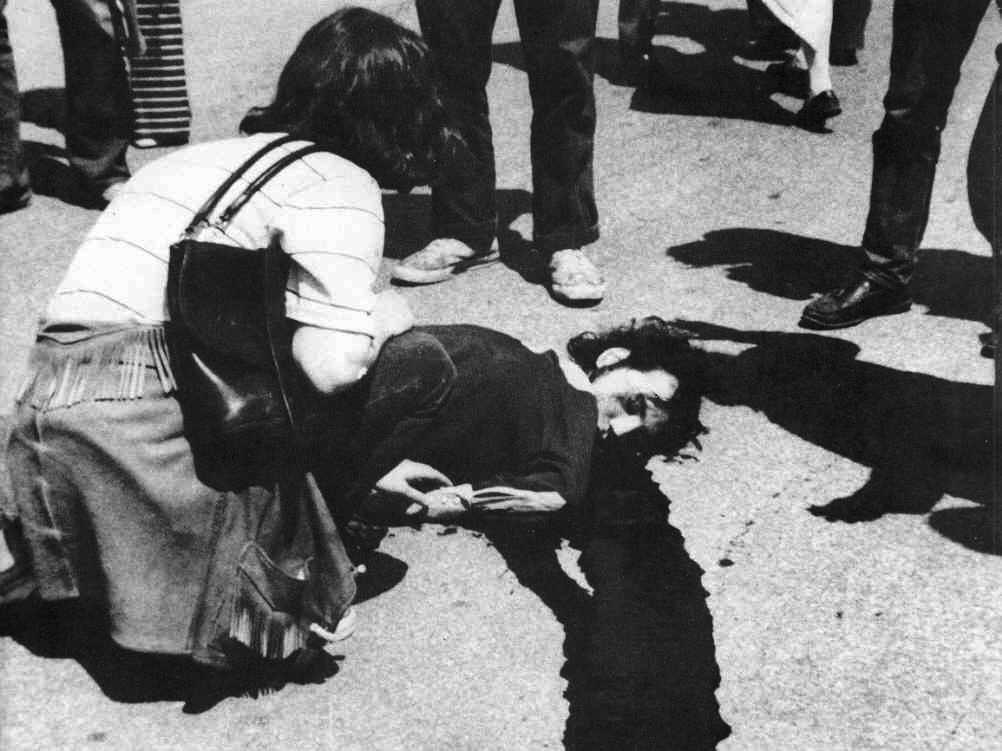

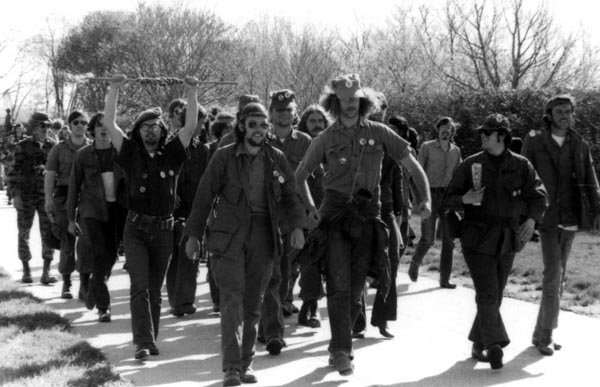

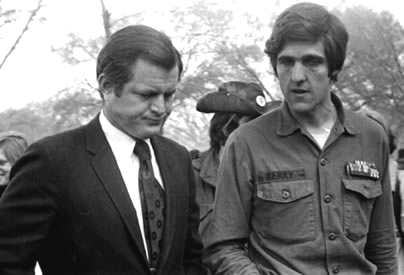

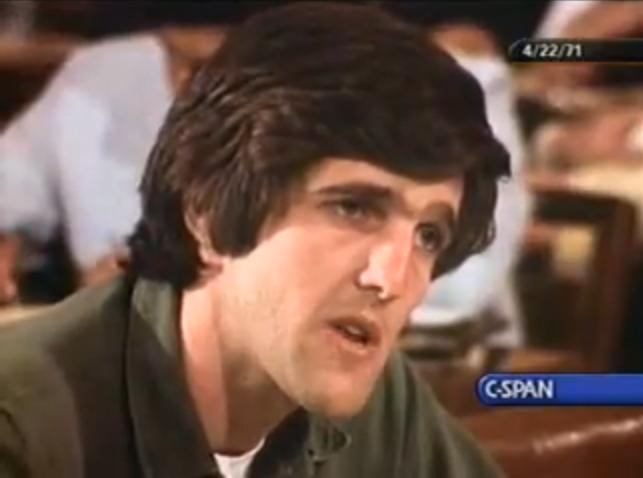

Nixon's

determination to wind down the Vietnam program

Nixon's

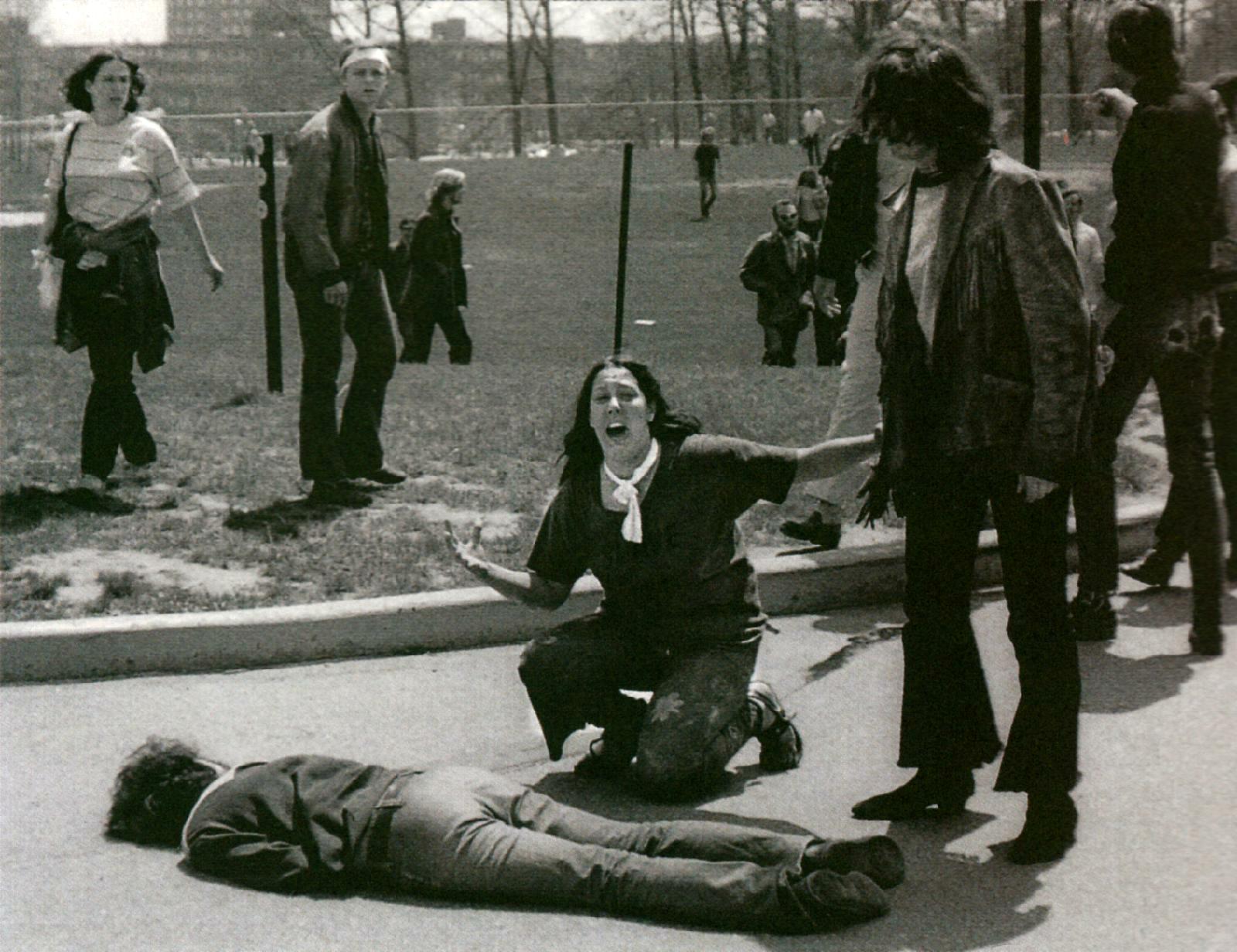

determination to wind down the Vietnam program Efforts to undercut Nixon's efforts at home

Efforts to undercut Nixon's efforts at home

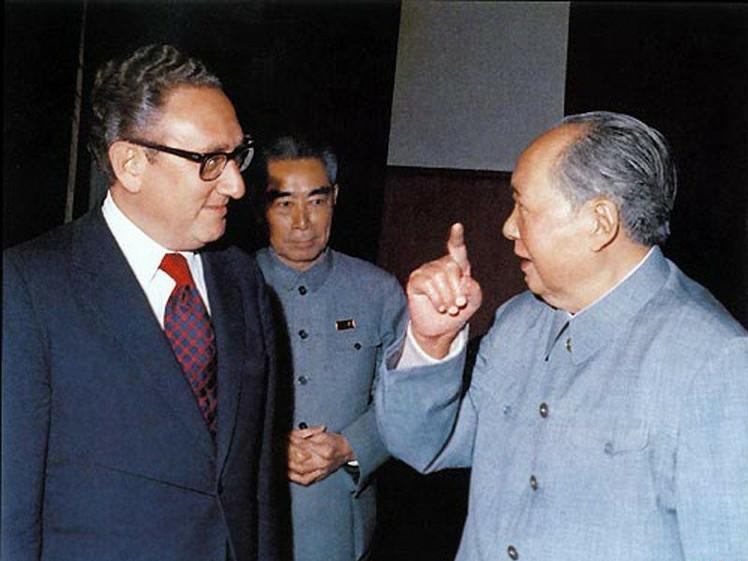

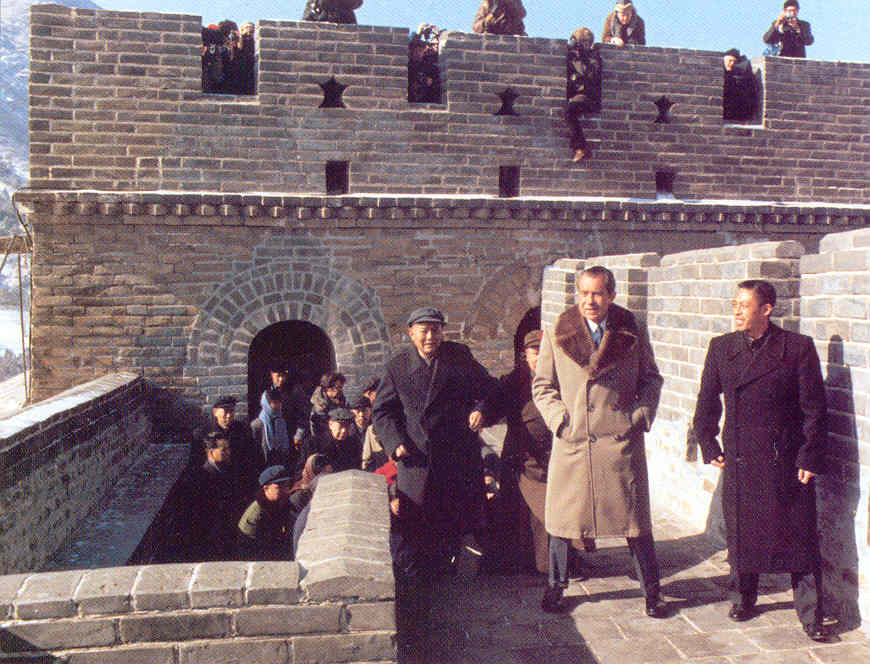

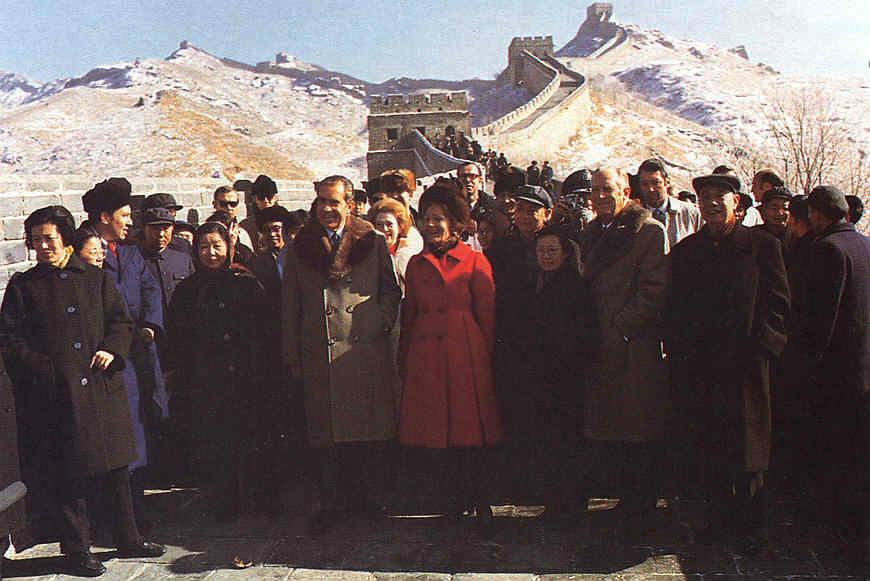

Nixon

decides to open relations with China (February 1972)

Nixon

decides to open relations with China (February 1972) Nixon pursues détente with the Soviets (May 1972)

Nixon pursues détente with the Soviets (May 1972) Nixon orders another round of bombing of North Vietnam (August 1972)

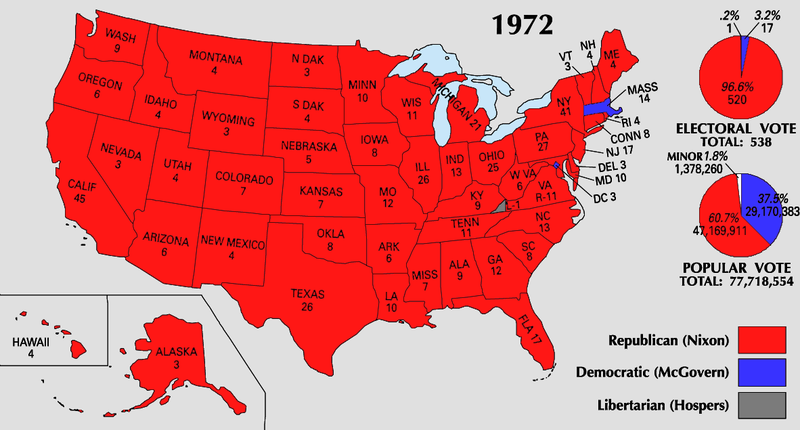

Nixon orders another round of bombing of North Vietnam (August 1972) Nixon's reelection (November 1972)

Nixon's reelection (November 1972) The Paris Peace Accords on Vietnam (January 1773)

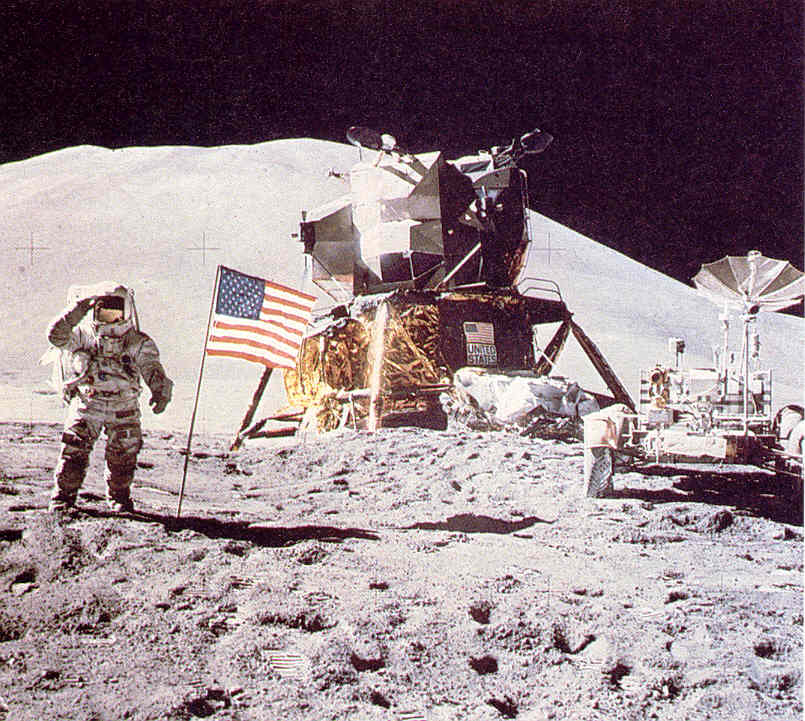

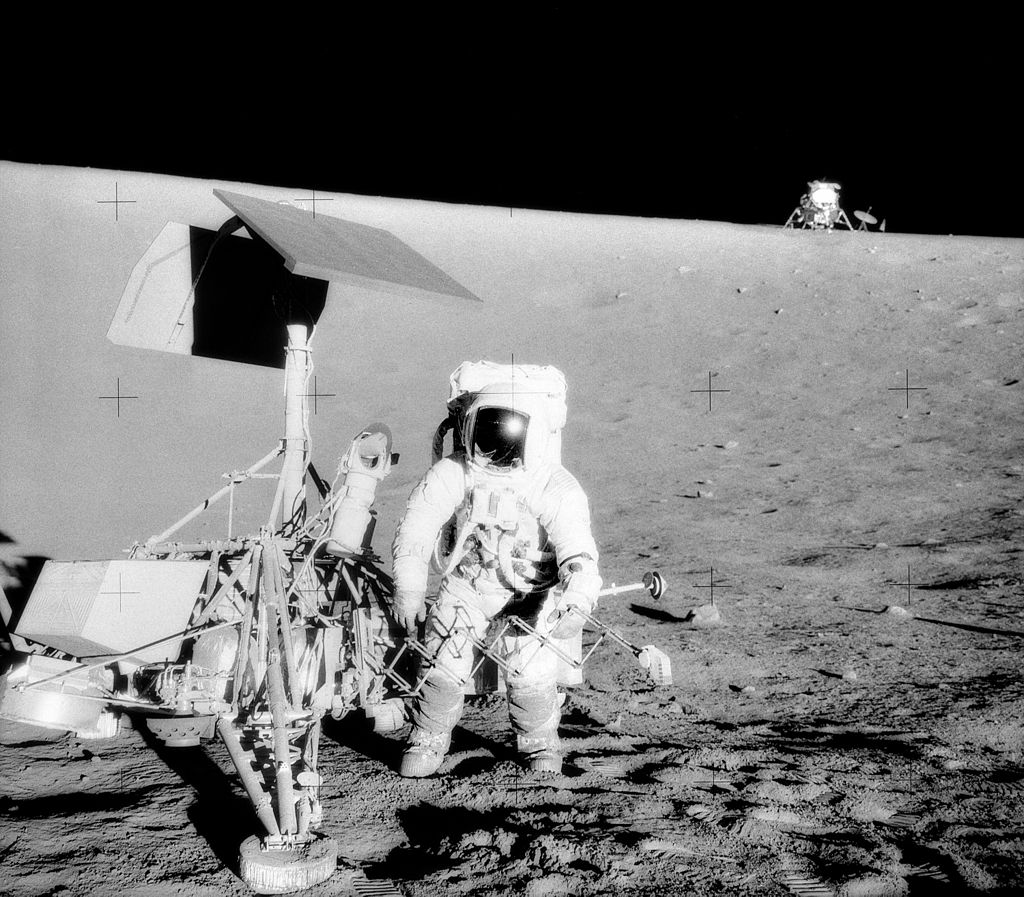

The Paris Peace Accords on Vietnam (January 1773) Nixon continues to push forward America's space

program

Nixon continues to push forward America's space

program

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges