|

|

Nixon and the political world immediately around him Nixon and the political world immediately around him Watergate Watergate Congress strips the President of his discretionary spending powers Congress strips the President of his discretionary spending powersThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 226-231. |

|

|

Nixon was a private man, disliking crowds and preferring to deal with the world quietly from behind closed doors. He clearly was at ease and happy when working personally with others. But when in front of a crowded pressroom, Nixon appeared nervous, defensive and cold, very uneasy in handling questions and clearly uncomfortable when sensing a challenge by members of the press. And this latter side of him was the side that became the public image of the man. Because of his personal nature he preferred foreign politics, usually handled personally from head of state to head of state, rather than domestic politics, which required much more of a public presence. Consequently, he largely turned domestic matters over to trusted cronies – which was a very risky move. Also, because of his sense that the press and other popular figures "were out to get him" (which was mostly true), he developed a very defensive spirit with respect to the political world immediately around him in Washington. He kept an enemies list and developed a siege mentality inside the White House as he found that despite his efforts to bring America to a post-Vietnam era of peace and prosperity, his political opponents never let up in their opposition (which he interpreted as a personal attack). Politics, of course, has always been highly adversarial, as Nixon himself knew well. Nonetheless knowing this did not lessen his sense of paranoia, a mentality that ultimately would destroy him. Indeed, his sense of there being enemies out there in American political society was not entirely fanciful. The Boomers' heroic hunt for authoritarianism in high places did not stop just because Johnson had left office. It simply switched to Nixon as he took office as President. He was the new imperialist in the White House. The fact that he had opened new relations with the Chinese, had lessened the tensions of the Cold War with the Russians, and had brought hundreds of thousands of American soldiers out of Vietnam did nothing to appease this vigilante mood of the Boomers (and their intellectual mentors). He received no thanks at all from them for his achievements Societal battle lines harden Youthful emotions were still running high in the street. And it seemed that the Boomers wanted to keep it that way. As the Beatles' song Revolution (1968) put it: You say you want a revolution, This spirit of radical protest pumped political adrenaline and helped maintain a revolutionary "high" among the Boomer youth. Then when Nixon and his Silent Majority of middle-class Vet voters soundly defeated McGovern and his vanguard of the Boomer revolution in the 1972 elections, the mutual animosity grew all the more intense between the two groups. The younger, rising Boomer world, and its youngish "Progressive" mentors, viewed Conservative America as if it had developed out of a very bad Fascist nightmare. For the Boomer-Intellectual party, possessing a virtually limitless contempt for the world of the Vets and their champion Nixon, there could be no moral compromise in this battle.

|

|

|

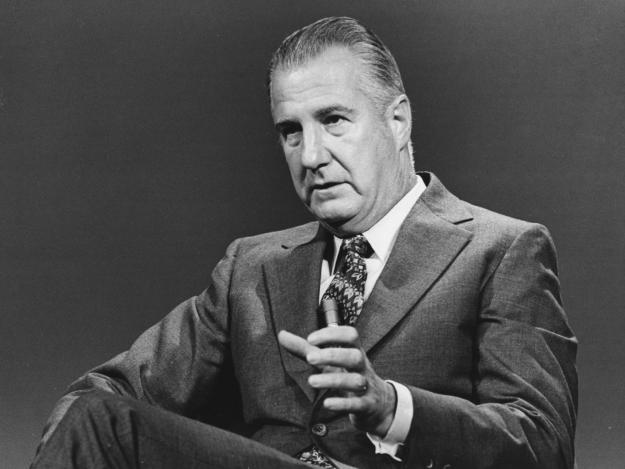

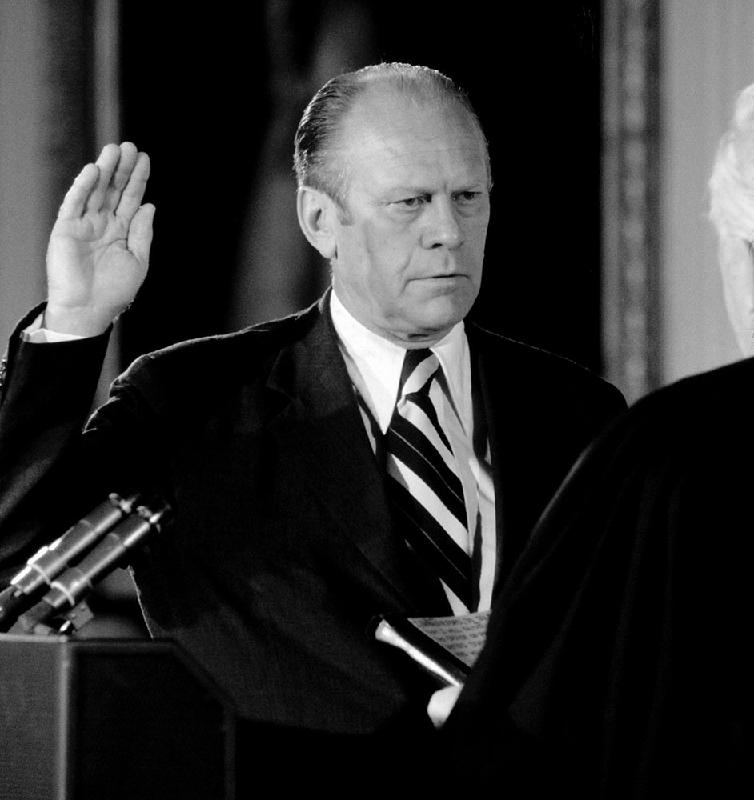

Opposing lines formed for battle when, during the summer of 1972 presidential election campaign, some of Nixon's re-election staff were caught by police undertaking "dirty tricks," by breaking into the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee in Washington, D.C., to plant bugs or listening devices. What was a totally unneeded1 event in the realm of dirty tricks – that sadly but also typically go on in high-stakes political campaigns – soon turned itself into a major scandal when two young Washington Post reporters (Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein) decided to pursue the story, a story leading hopefully all the way to into the White House if possible. In this they had inside FBI help in unfolding the story as one after another individual on Nixon's campaign staff was implicated in the affair. With the trial of the Watergate burglars finally beginning in January of 1973, immediately the cry went up for the strongly Democrat-controlled Congress itself to look into the whole affair. The person seemingly now leading the Democratic Party, Senator Ted Kennedy, sponsored a resolution in February of 1973 to set up a select committee2 of four Democrats and three Republicans to investigate the activities of the 1972 Nixon campaign committee. At this point Nixon himself had done nothing that could have produced any reason to have him impeached. For Nixon, the difficulty arose only when the Kennedy-inspired inquiry into the event to see if it would lead to the White House actually got underway. At this point a huge political storm quickly developed between Nixon and those called to investigate his 1972 campaign operations. To the understanding of Congress, any attempt to impede a wide-ranging search for irregularities in his conduct of his office would itself automatically place that activity in the category of "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors" (Article II, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution). And indeed, by very instinct, Nixon would do what he could to head off this search of him and his office for any evidence that an investigative team could find to have him removed from the presidency (and even sent off to jail afterwards as a private citizen). Only at that point would Nixon find himself in a position where his Congressional (and press) enemies would have supposed grounds to bring down "the evil president." In April of 1973, sensing that the axe would likely fall on him, Nixon's own Legal Counsel, John Dean, offered himself as witness against the president, claiming that Nixon himself had actually authorized a post-event coverup of the affair (though he himself had no actual evidence to present), and kept an enemies list of his opponents (not exactly uncommon in politics), supposedly indicative of Nixon's general abuse of power. This was the kind of political feed that not only Congress but also the press was looking for. Indeed, a political feeding frenzy was under full go at this point. Sensing the world closing in on him, Nixon that same month began the firing of key White House and Cabinet officials, supposedly action on the president's own part to distance himself from those directly involved in the Watergate affair. But whatever he hoped that might achieve instead proved pointless, actually making these firings appear to be more like some kind of admission of guilt in high places. By May of 1973 the Senate was ready to go public in their investigation, with a series of hearings followed widely across the country. When in July it was revealed that Nixon had tapes recording conversations he had had with various staff and government officials (as part of the material he wanted to have to help him later write his White House memoirs) Congressional pressure was on to get those tapes, which Nixon declared were personal (indeed presidential conversations were always considered to be sensitive and thus out of the reach of Washington politics). But the Special Prosecutor Harvey Cox issued a subpoena for those tapes anyway, which Nixon resisted. Finally in October an angry Nixon (this battle between the White House and Congress had now been going on for nine months) ordered his Attorney General Eliot Richardson to fire Cox (the Attorney General indeed did have such authority in this matter), but Richardson resigned instead. The same happened when Nixon then turned to the Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus. Finally, Solicitor General Robert Bork carried out the order, the action actually hurting rather than helping Nixon in this battle. In any case, Bork then had to appoint a new Special Prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, and the battle continued. By this time, Watergate had become high-drama politics. Nixon now seemed like a man on the run. Americans were glued to their televisions (the afternoon soap operas had even given way to the televised Congressional hearings) as both houses of Congress deliberated on the Watergate matter. In short, a public trial was being held, even before formal charges could be presented and an indictment actually issued. But all the drama was putting the names and faces of multiple Congressional officeholders in front of the voting public. It was great political publicity, seeing these individuals defending American democracy against the imperialist presidency. Meanwhile the Department of Justice

announced that it was investigating Vice President Spiro Agnew for

taking bribes for government contracts when he previously served as

Maryland governor. In early October Agnew resigned, and that same day

Nixon announced that he was appointing the well-liked Michigan

Congressman (and head of the Republican Party in the House) Gerald Ford

as his vice president. In November the appointment was approved by both

houses of Congress by huge majorities. The following March (1974) the case moved beyond the White House and Senate battlefield when a Washington, D.C. grand jury indicted seven of Nixon's closest staff-members of conspiring to hinder the Watergate investigation, after two others (including Dean) pleaded guilty to the same charges. Finally in April Nixon agreed to release

written transcripts of the much-sought-after White House conversations.

Deeply shocking to the public was Nixon's use of vulgarity, and

comments he had made about this social group and that religious group.

At this point Nixon's embarrassed Republican supporters in both

Congress and in the nation began to drift away from him.3 But even worse for Nixon, conversations Nixon had held with his legal advisor Dean and others revealed that Nixon had indeed been involved in the Watergate coverup, at least to the extent that Nixon back in March of 1973 had been part of a discussion concerning the demand for hush money coming from E. Howard Hunt – and potentially all of the Watergate burglars – blackmail funds that might possibly have to be paid out secretly to keep them quiet about any connections they might have had with the Nixon team. This was the "smoking gun" the prosecutors (and the press) were looking for. They finally had Nixon. 1However,

the break-in was likely motivated in part by the hope to find precise

information about Democratic National Chairman Larry O'Brien's exact

connections (if there actually were any) with the incredibly wealthy

but highly secretive Howard Hughes. It seems that the Democrats had

been feeding information to Nixon through his rather improvident

brother Donald that Nixon was going to lose the 1972 campaign because

O'Brien had damaging information about Nixon given him by Hughes –

including evidence that the gift of $205,000 from Hughes back in 1957

to rescue Donald's failing restaurant business was actually given as a

political favor for then Vice President Nixon. Such information – true

or not true – would have damaged the 1972 Nixon campaign tremendously.

However, the whole thing was likely a hoax. But this was the kind of

misinformation that the Democrats were hoping would put Nixon in a

self-destructive frenzy. Unfortunately, it was not untypical of the

kind of antics that go on in races for political office. But in any

case, it did succeed after all (quite ironically) if this is what got

the Nixon team to attempt the disastrous Watergate stunt. 2For

various reasons, however, it would be Sam Erwin, not Kennedy, who would

chair the Senate Committee doing the investigation. One explanation

offered was that having Kennedy head up this committee, a man who had

high hopes of being the Democratic Party's Presidential nominee in the

1976 national election, might make the investigation look partisan! An

unspoken explanation was that Kennedy's own moral credentials since the

Chappaquiddick incident were hardly admirable. 3Political

morality can be very selective. Truman and Johnson were just as likely

to use such salty language and offer unkind opinions on this group and

that when president. And this kind of behavior behind Washington

politicians' closed doors was not uncommon – including among some of

those Congressmen who sat in judgment of Nixon. It is just that in

general such privileged conversations were never allowed to leave

through those closed doors. This does not justify Nixon's language or

his opinions. But it raises questions about the level of political

hypocrisy in Washington.

|

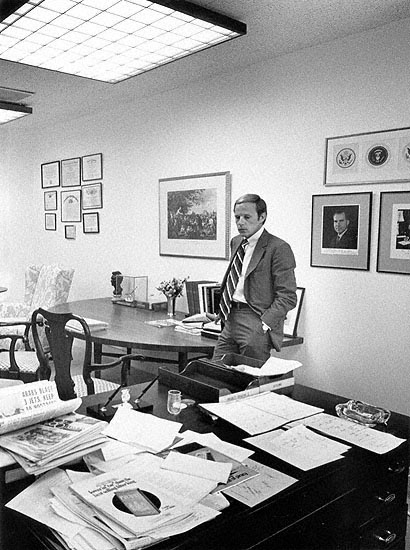

White House

Legal Counsel John Dean

– September 17, 1970

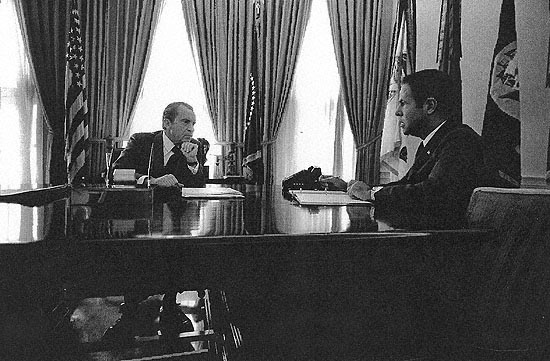

Nixon and H.R.

Haldeman – White House

chief of staff – February 10, 1971

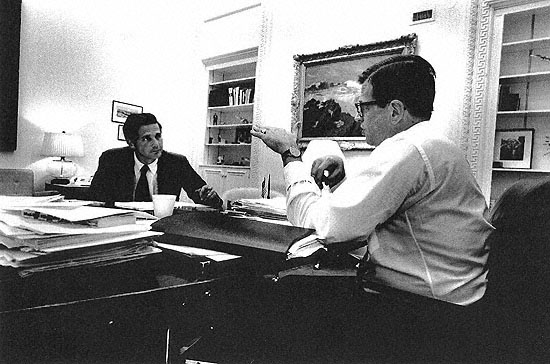

Jeb Magruder

and Special Counsel to

the President Chuck Colson – June 1972

Nixon's Committee to

Re-elect the President

(CRP / also known as CREEP!) – summer of 1972

Headed by former Attorney General John

Mitchell

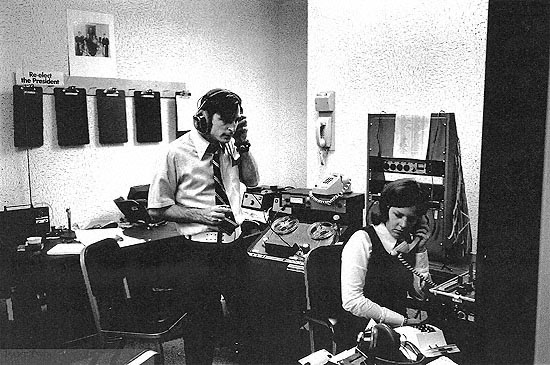

Monitoring tapes

and conversations at

the CRP

The Watergate

apartment complex –

Washington,

D.C.

where the Democratic national headquarters

were located

Watergate begins to reach

up to the

White House

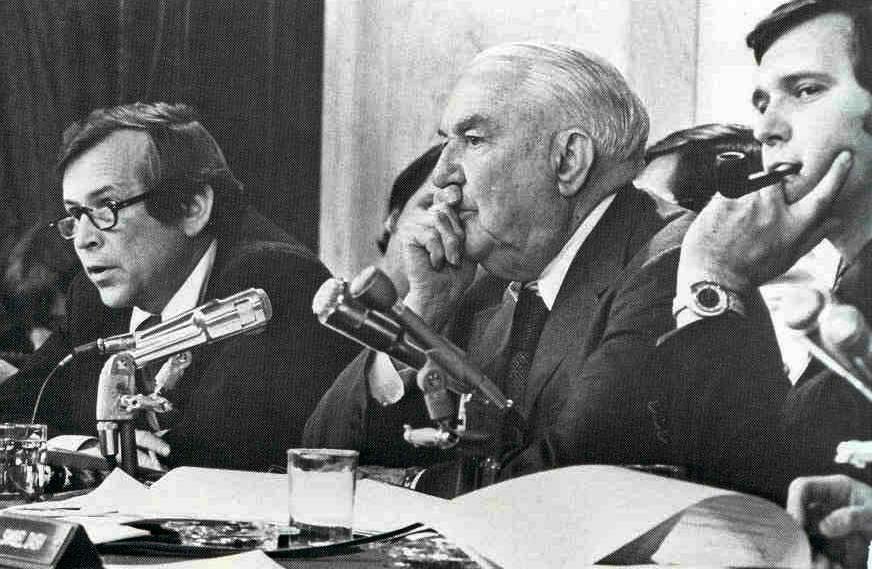

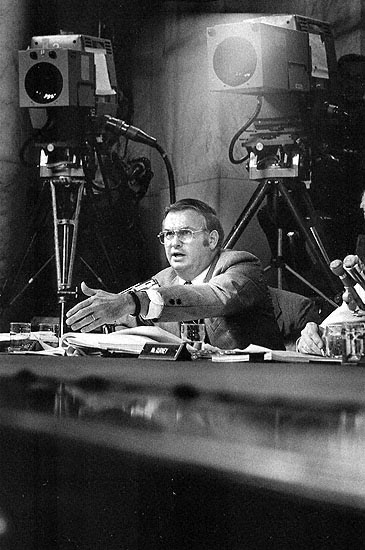

The Senate Watergate Hearings

– Summer of 1973

(Senate Select Committee

on Presidential Campaign Activities)

Republican Senator Howard

Baker and Democratic Senator and Committee Chairman Sam Ervin

directing the Senate Watergate

Hearings

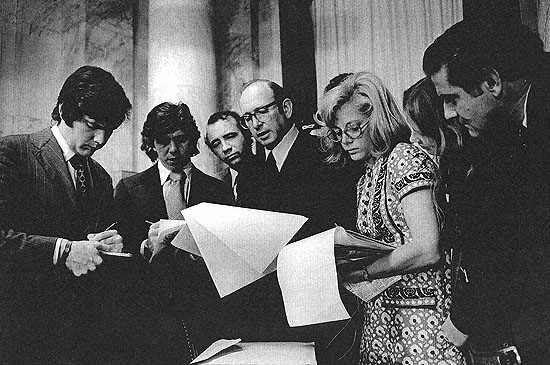

Senate Chief

Counsel Samuel Dash (center)

conferring with

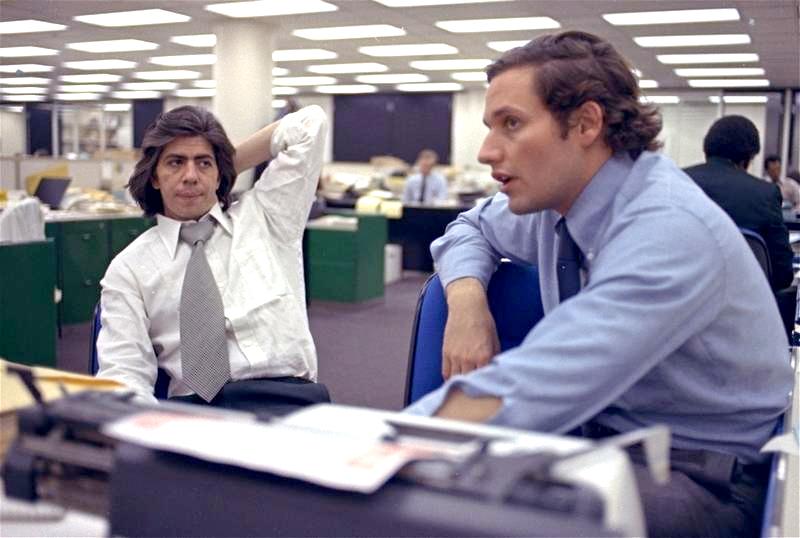

Washington Post reporter Carl

Bernstein and CBS correspondent Leslie Stahl – June 3, 1973

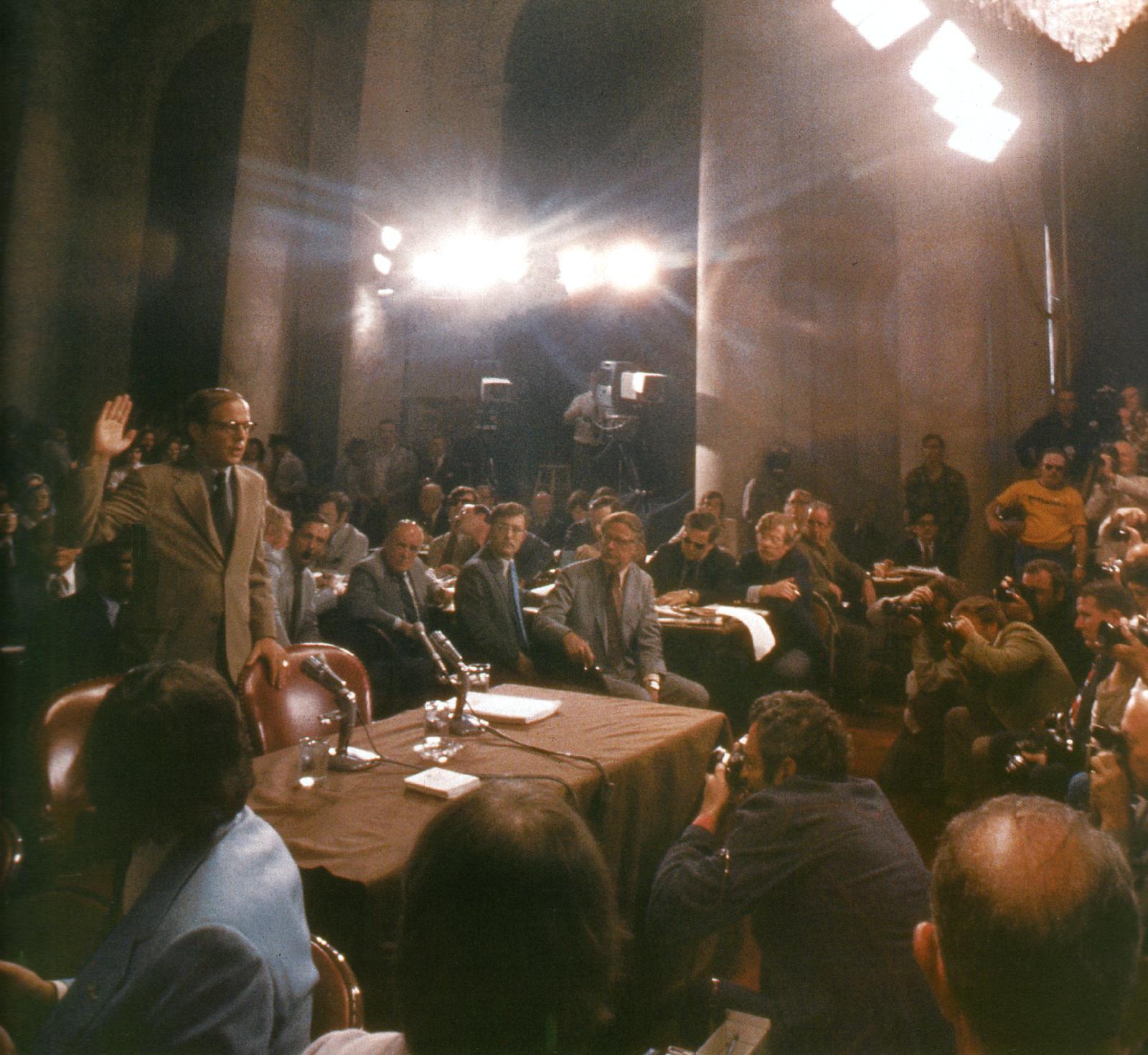

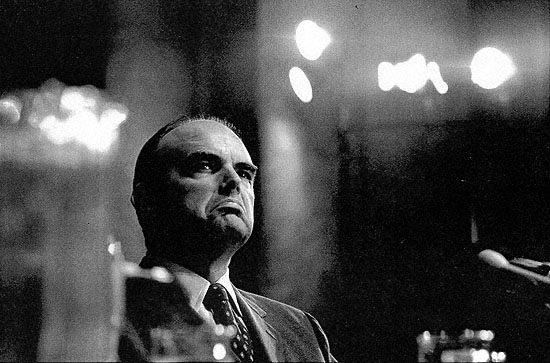

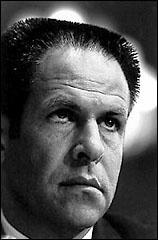

White House Legal Counsel

John Dean at the Senate Watergate hearing

John Dean testifying against

his former boss Nixon at the Senate Watergate hearings

John Dean testifying at the Senate Watergate Hearing – June 1973

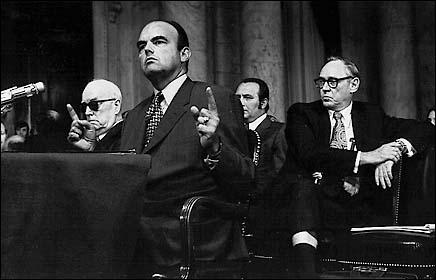

Former

domestic policy advisor John

D. Ehrlichman testifying before the Senate committee

July 24, 1973

John D.

Ehrlichman before the Senate

committee

H.R. Haldeman

testifying before the

Senate committee

Senator Weicker – July 30, 1973

|

|

While all of this Watergate political drama was underway, Congress had already begun to flex its muscles against the "imperialism" of the White House in other areas. Congress moved to take away the President's discretionary spending powers, his powers to impound funds which Congress had voted to be spent. Since ancient times, the contentious issue of government spending had normally been one arising from the overspending tendencies of the heads of state (kings, emperors, etc.). The role of legislatures was typically understood to be to rein in that spending, generally by refusing to authorize revenues for kings or emperors by way of new taxes. When the American Constitution was set up it was done so with the idea in mind that the House of Representatives would continue to play that restraining role within the national government. All authorizations of government spending had to originate in the House of Representatives. The President could spend no more than he was authorized by the House. But what was happening under Nixon was that he was underspending, not overspending, with respect to the operations of government. He had promised to cut back on government spending, and did so by simply impounding or refusing to release funds for a number of spending programs that he felt were unnecessary or at least unnecessarily costly. Congress fumed. Legislative programs that brought jobs and spending back to the Congressmen's home constituencies (plus also jobs in Washington, which the Washington bureaucracy protected at all costs) were what they depended on to stir support for their incumbency. Legislators could always point proudly to the amount of federal spending ("pork barreling") that they had directed back to the folks at home. Being that the President was in deep trouble over Watergate and on the political defensive on all political fronts, Congress decided to move, to bring "responsibility" to federal spending. They passed the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act which forced the President to get Congress's consent to impound or not spend any of the amount authorized in the Congressional budget. They thus stripped the President of important financial powers that reached all the way back to 1801, at the time of Jefferson's presidency. And they did this in the name of democratic anti-imperialism. They also set up the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to stay on top of exactly what was being spent and where. The idea was to follow up on details to make sure that the President was obeying Congress's spending directives. But the CBO would also, in the future, come to have the unintended effect of giving critics of out of control Congressional spending – in particular, lavish pork barrel programs of the Congressmen – plenty of detailed facts to work with!

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges