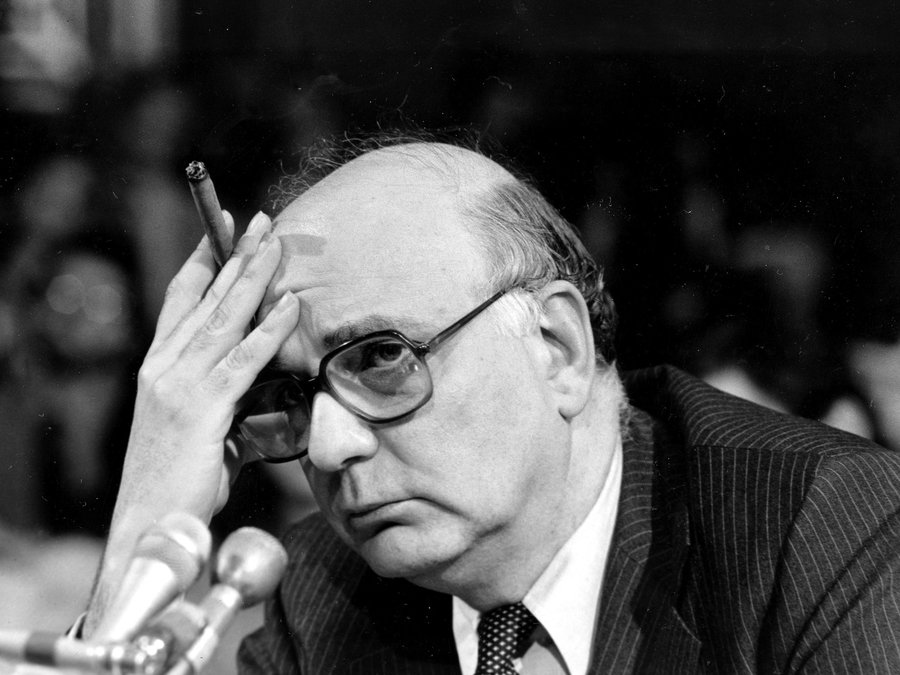

But ultimately what guaranteed that the Carter

presidency would be a one-term presidency was the economy. Carter's own

appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker decided in the latter

part of 1979 to attack the high inflation set loose by the huge

three-fold oil price hike (caused by Iran's withdrawal from the

international oil market) – and the need of the rest of the industrial

economy to raise prices on their products in order to maintain some

degree of profitability in the face of the new energy costs. Volcker

decided that he was going to solve the problem of runaway inflation –

by the Federal Reserve's putting into play a huge tightening of

America's dollar reserves, driving interest rates astronomically high.

He believed that this would indeed kill inflation (if it didn't also

destroy the American economy!).

Thus by cutting back severely the amount

of dollar reserves available for lending to America's banks, Volcker

drove the Federal Reserve discount rate all the way to 20 percent, in

turn forcing the large commercial banks (all of whom borrowed from the

Federal Reserve to maintain their own supply of lending power) to have

to set their prime rates at 21.5 percent, for even their best

industrial customers. This strategy Volcker called "monetarism."

Volcker's "monetarist" (tight money)

strategy was designed to make Americans feel poor enough that they

would stop spending, and thus presumably force down prices, and

supposedly inflation with it. This was also supposed to strengthen the

dollar. At least that was the theory Volcker was supposedly working

under.

What this actually meant was that

industrial enterprises, facing a three-fold increase in their energy

costs in their operations, now found themselves also having to make

huge interest payments on the bank loans on which their businesses

depended. To survive at all, to meet skyrocketing operating costs (now

both energy and interest expenses), they were forced to have to raise

(not lower!) prices on their products quite considerably – to make

enough money just to barely stay in business. In short, Volcker's

monetarist strategy served to drive inflation even further upward.

But far worse, with car loans and house

mortgages borrowed from American banks now running at Volcker's new

rates (forcing the banks' 30-year mortgage rates to run at about 16

percent and industrial prime lending rates up to 21 and 22 percent),

Americans decided to hold off buying a new car or buying that new home.

Thus now with few customers coming through their doors, businesses

found themselves in deep trouble. Soon these businesses began to shut

down, one by one.

Consequently, everywhere the economy not only slowed down, as Volcker intended, it plunged downward in a death spiral.

But Volcker was determined to hang tough

until he single-handedly had "shaken the last of inflation out of the

economy" (or so he said). That was except for the brief period over the

summer of 1980 when Volcker dropped interest rates, to release the

economy from his imposed restraints and thus get it up and moving again

in time to get Carter re-nominated to the Democratic Party ticket. The

economy immediately responded by picking up again.

But before the November elections rolled

around, Volcker decided to take the interest rates right back up again,

plunging the economy back into deep recession, which in turn had the

Americans going to the polls feeling very grumpy. This helped produce a

very humiliating Carter defeat in the 1980 general elections.

But tragically Volcker's monetarist

strategy also helped worsen what were at this point already shaky

American heavy or basic industries (steel, chemicals, cloth,

construction), forcing many businesses either to shut their doors,

never to reopen, or go "offshore" with their operations (to Japan,

India, Thailand, etc.), never to return to America.

And banks, at first making huge windfall

profits on the basis of the new interest charges imposed on their

customers, soon found that they too were losing customers – as no one

came to the banks looking for mortgages or car loans.

And commercial and industrial

bankruptcies were not what the banks wanted either. Commercial

bankruptcy now got pushed onto the creditor banks who had formerly

funded these now-bankrupt companies more than they were now worth.

True, the banks received title to these bankrupt companies. But what

were the banks to do with these companies? They could not sell them to

investors willing to take them off their hands. There were no such

investors willing to take on the financing necessary to purchase even

these bankrupt companies. Thus it was that American banks now found

themselves also in debt. They could, of course, borrow from the federal

reserve. But what bank was foolish enough to take on federal reserve

loans running at times almost at 20 percent interest? Within short

order, American banks also began to fail one by one.

Thus it was that the only thing that

Volcker's monetarism actually achieved was first the ruination of the

American industrial sector and then the collapsing of much of America's

financial sector as a follow-up.

America now fell into a deep recession,

one that American businesses and consumers had no idea of how to climb

out of. Certainly Volcker's federal reserve bank was of no help in

addressing the problem. At this point it was one of the chief causes of

the problem!

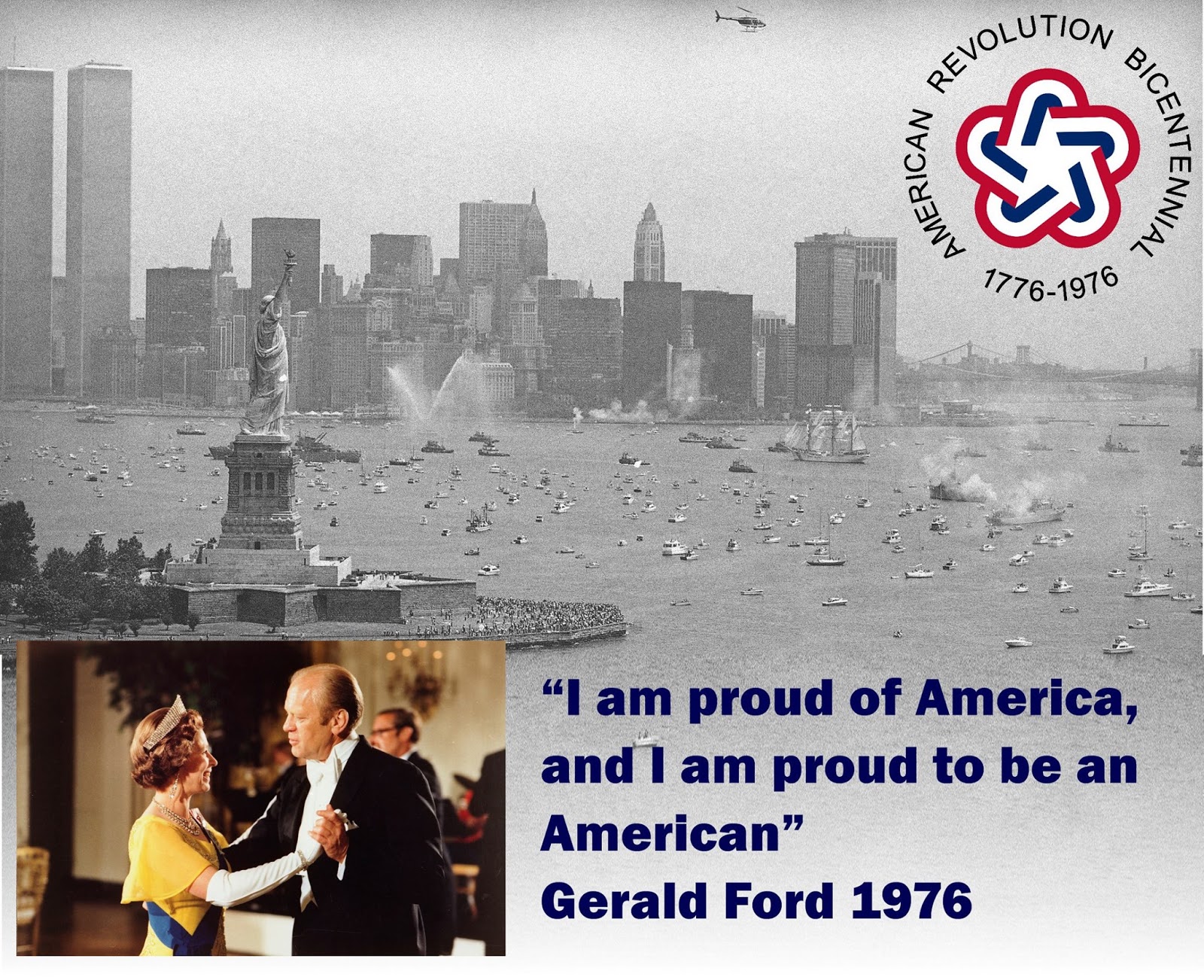

The American Bicentennial – 1976

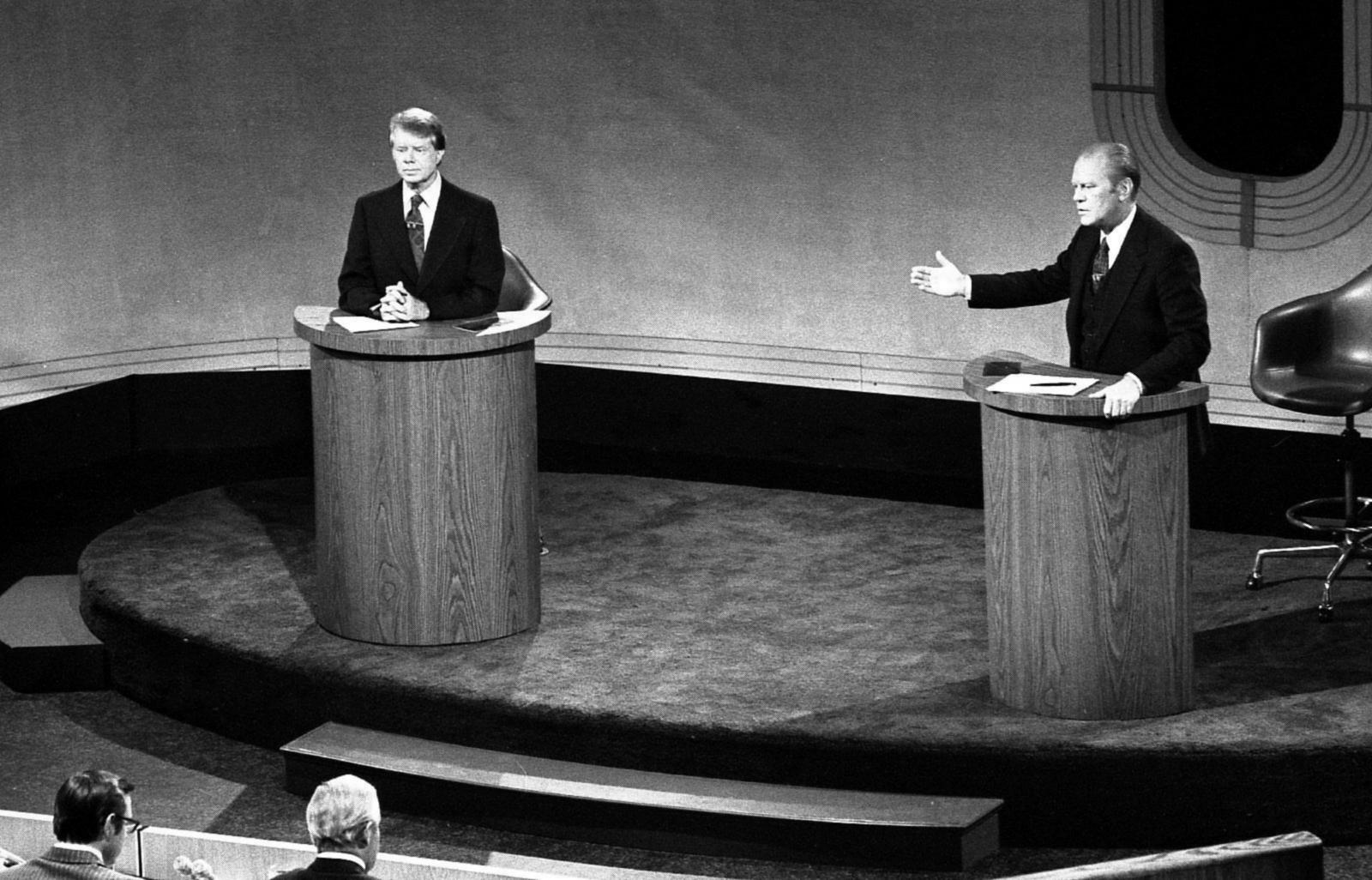

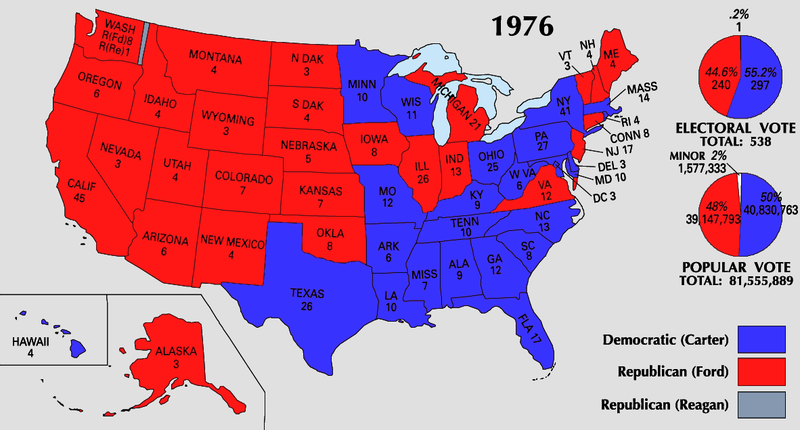

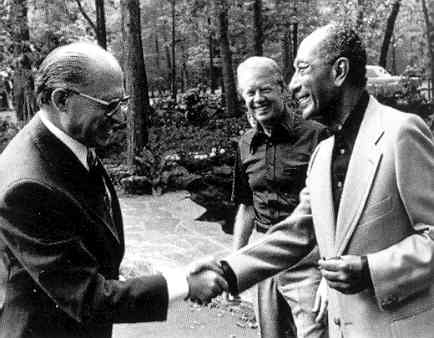

The American Bicentennial – 1976 Jimmy Carter and the national elections of 1976

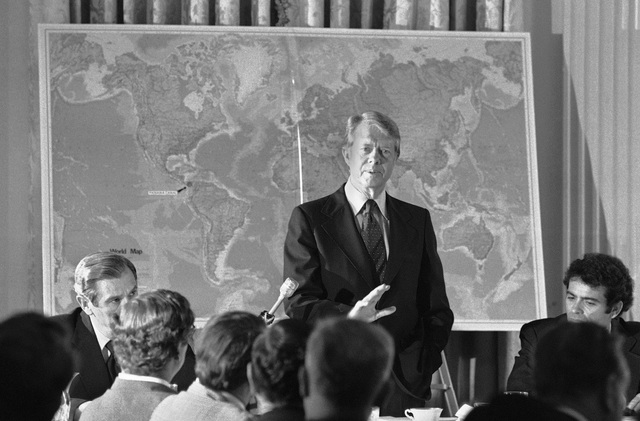

Jimmy Carter and the national elections of 1976 Carter proposes a foreign policy of "Morality"

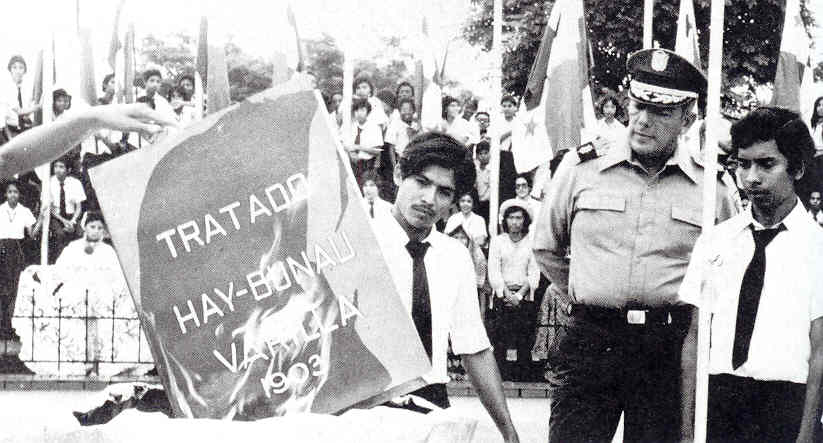

Carter proposes a foreign policy of "Morality" The surrender of the Panama Canal

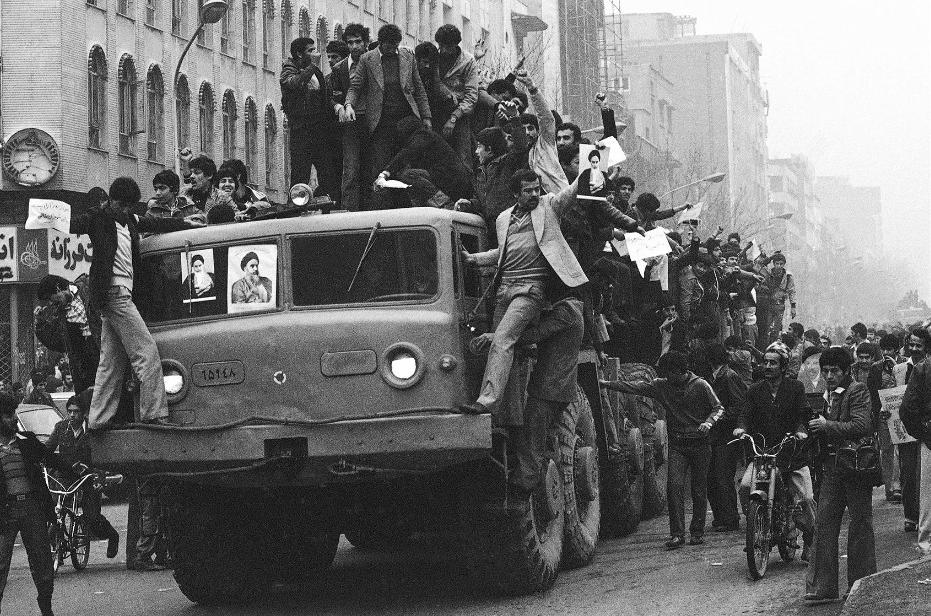

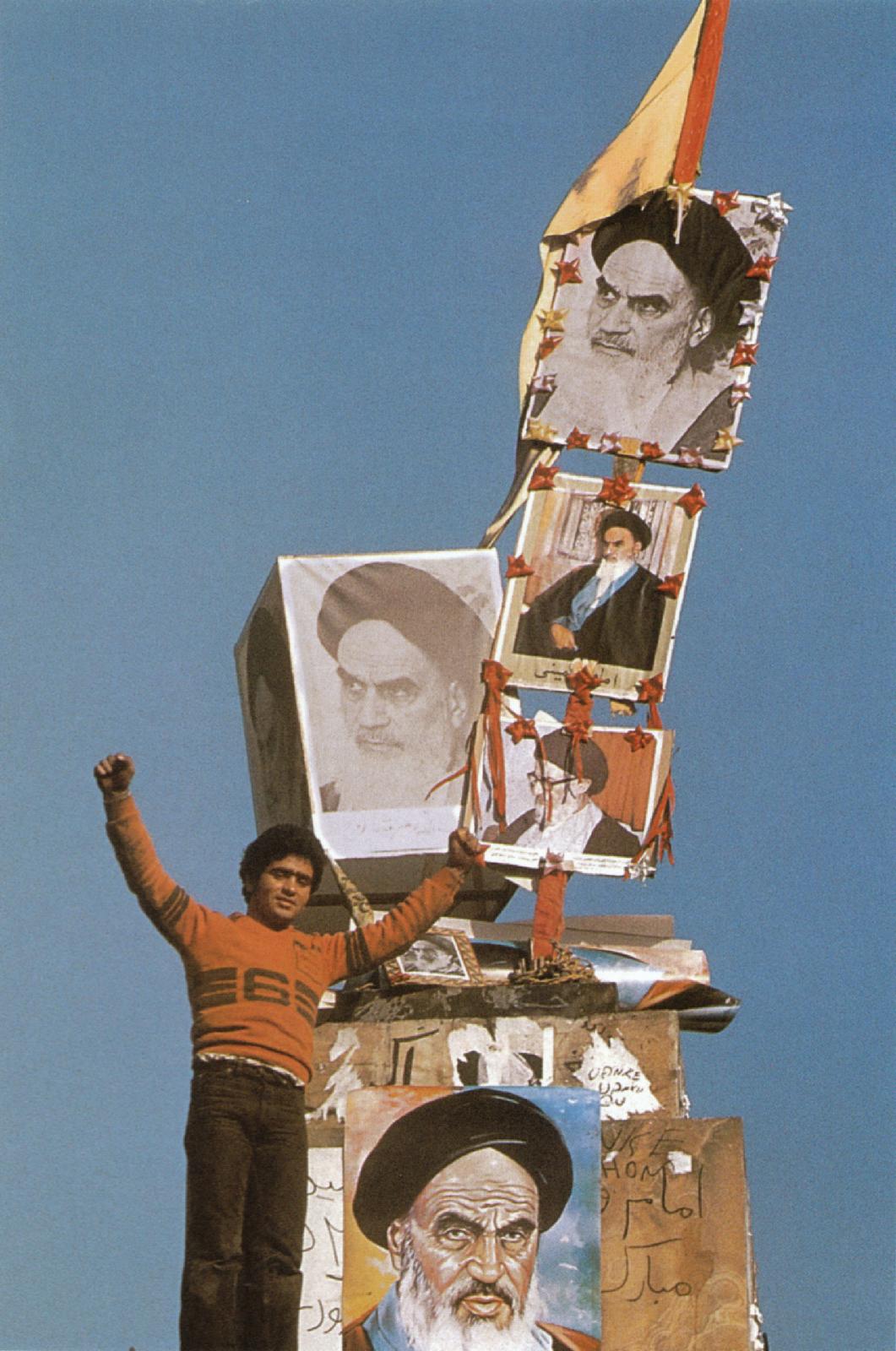

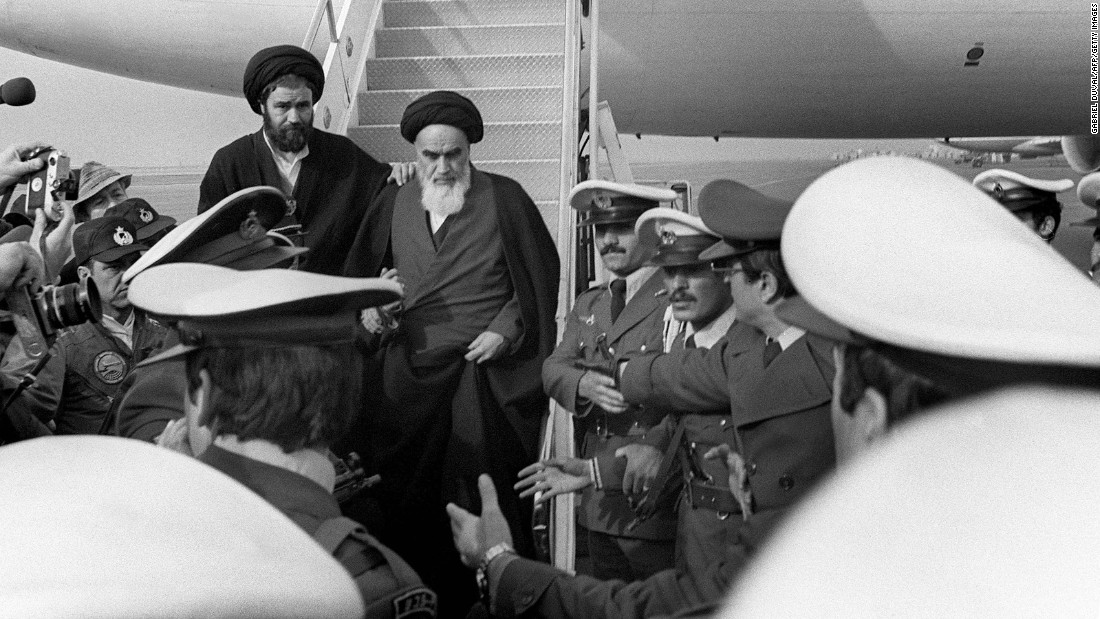

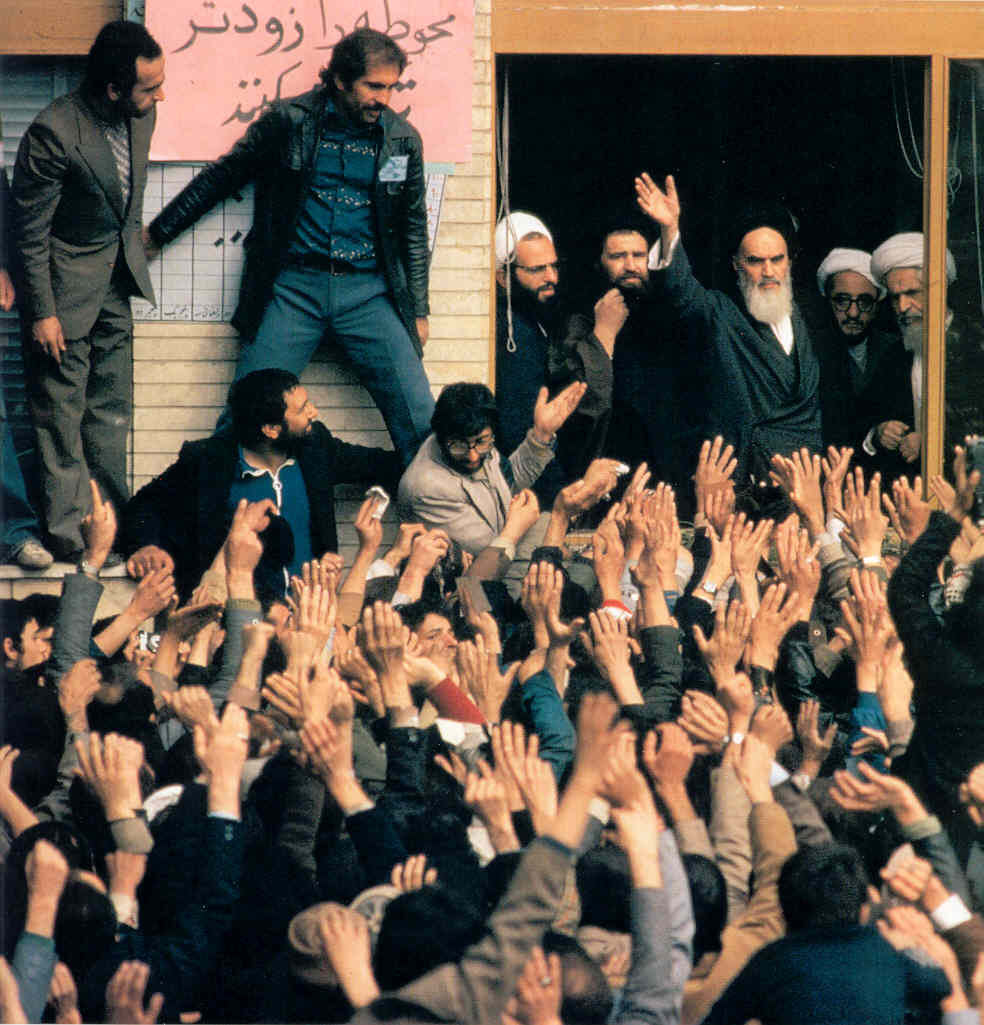

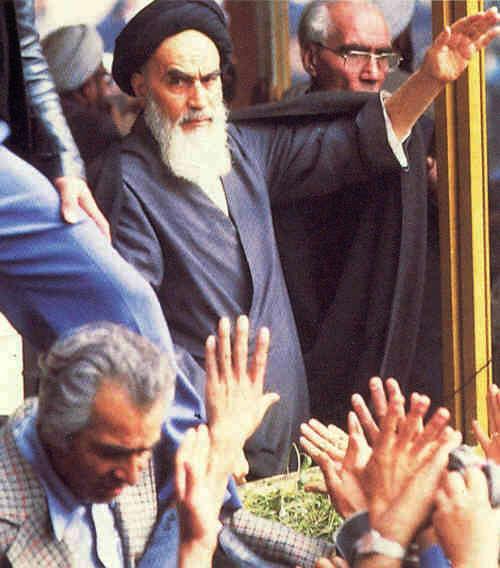

The surrender of the Panama Canal The fall of the Shah of Iran

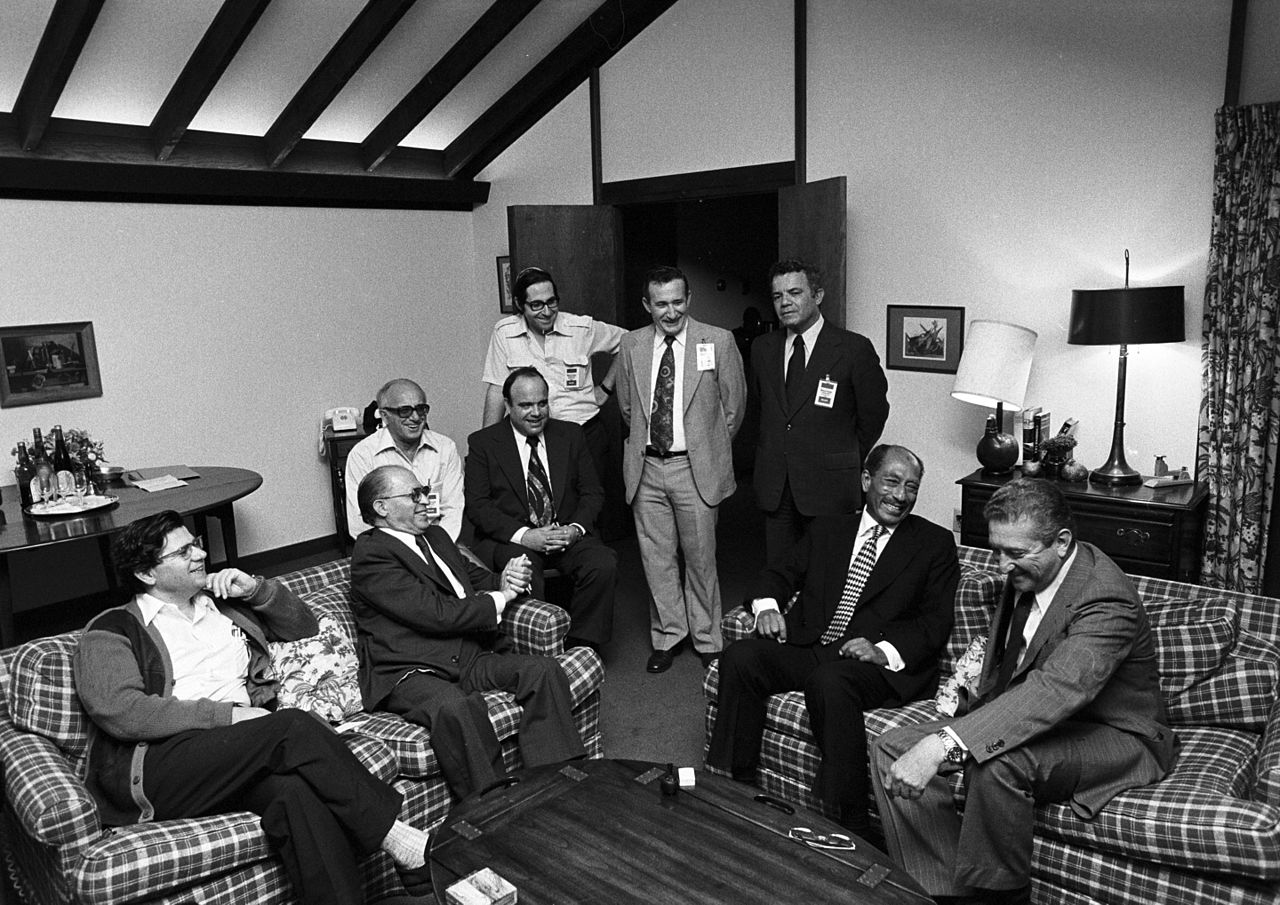

The fall of the Shah of Iran Other international issues during the Carter years

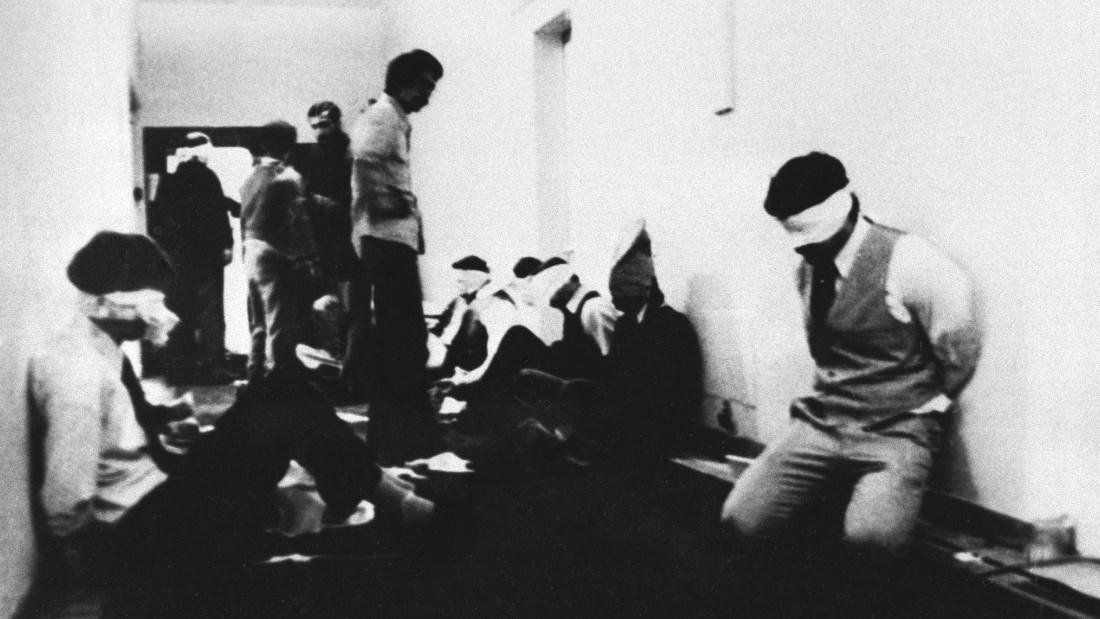

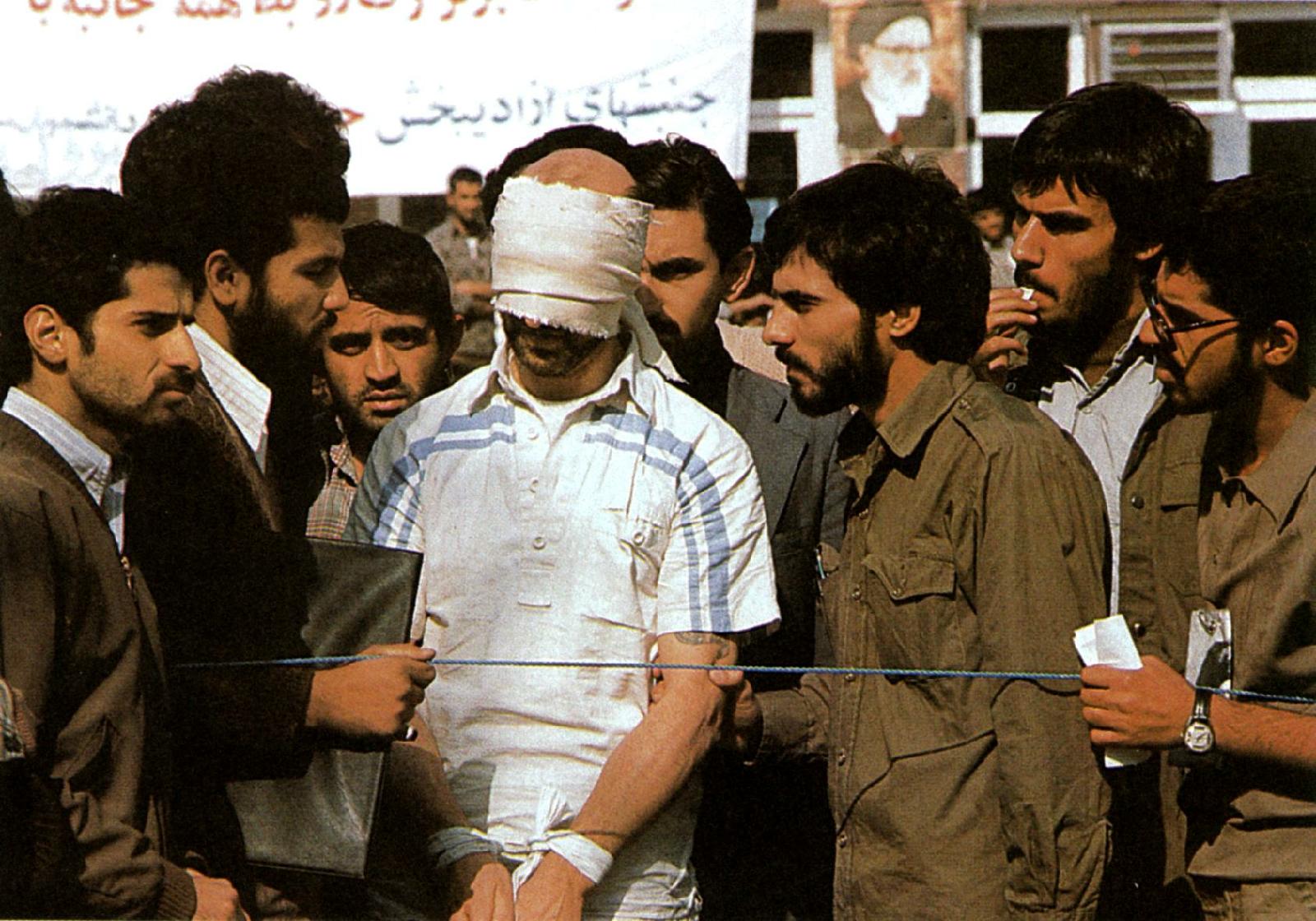

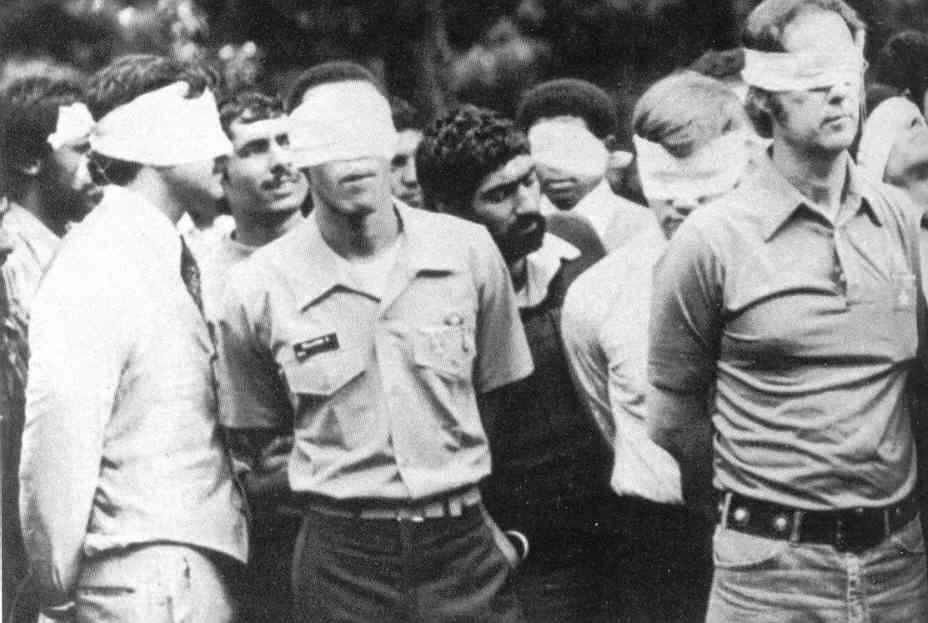

Other international issues during the Carter years American diplomats imprisoned in Iran

American diplomats imprisoned in Iran  Drooping American morale

Drooping American morale  Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue?

Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue? Other political causes continue to advance themselves in America

Other political causes continue to advance themselves in America

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges