The huge Polish reception

to Pope John Paul II's visit in June of 1979

constituted a huge challenge

to the authority of the Polish Communists

Then, led by Lech Walesa's and his dock-workers' union "Solidarity,"

Polish workers give serious

affront to the Communist system in Poland

Lech Walesa leading the strike

of workers at the Lenin Shipyards in

Gdansk, Poland

– August 30, 1980

Striking workers at the Lenin

Shipyard – 1980

Polish military under Gen.

Jaruzelski, fearful of a Soviet military reprisal (such as occurred in

Czechoslovakia in 1968), retake Poland from Solidarity – December 1981

But things are also stirring in the Soviet Union, as the Soviet Empire's leadership

changes hands rapidly over the course of the early-to-mid 1980s

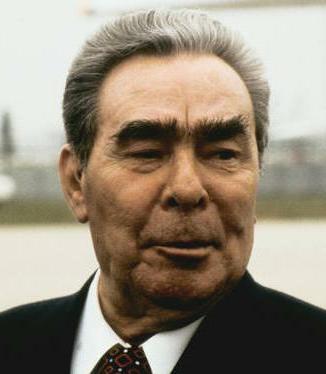

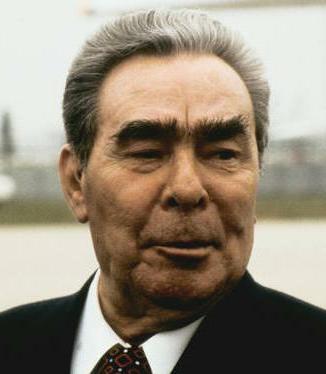

Leonid Brezhnev

Communist Party Chairman

1964-1982

|

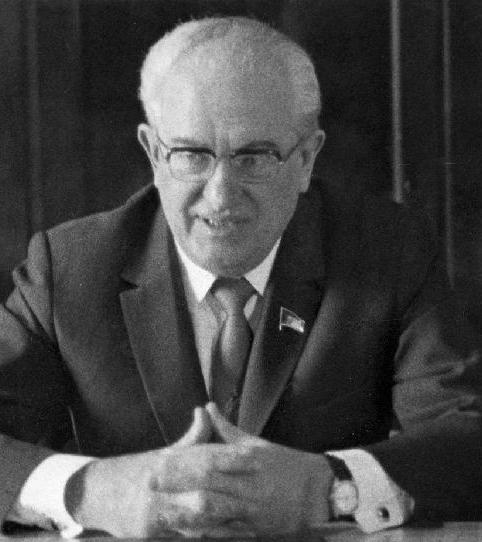

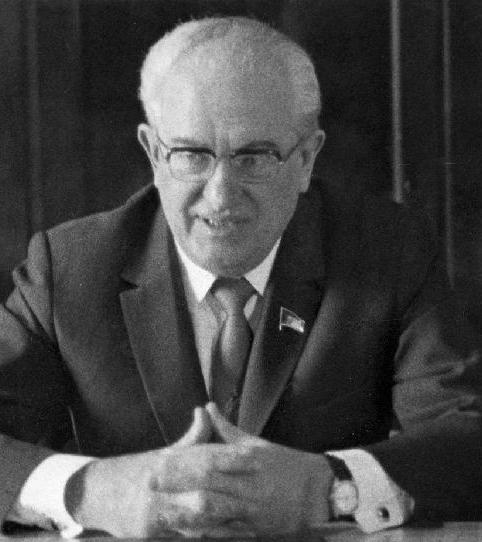

Yuri Andropov

Communist Party Chairman

1982-1984 |

Konstantin Cernenko

Communist Party Chairman

1984-1985

|

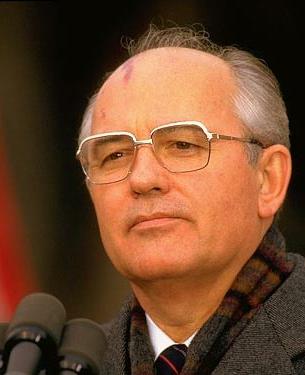

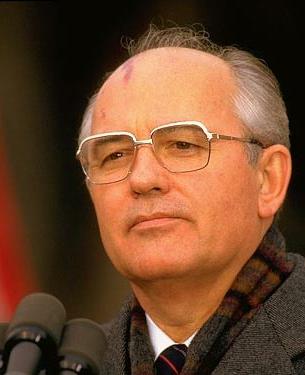

Mikhail Gorbachev

Communist Party Chairman

1985-1991

|

Also ... the Soviet position in Afghanistan begins to come apart (early 1980s)

Babrak Karmal

chairman of

Revolutionary Council of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

(1979-1986).

The Soviets had installed

this Afghan Communist leader in Kabul in 1979 in the hopes

that he might

keep more effective control over

Afghan politics than had

his Communist predecessor,

Hafizullah Amin – whom Soviet troops assassinated

when they first invaded the country in 1979.

Soviet paratroopers aboard

a BMD-1 in Kabul

Soviet helicopters working

with Soviet tanks in Afghanistan

Afghan village destroyed

by Soviet troops

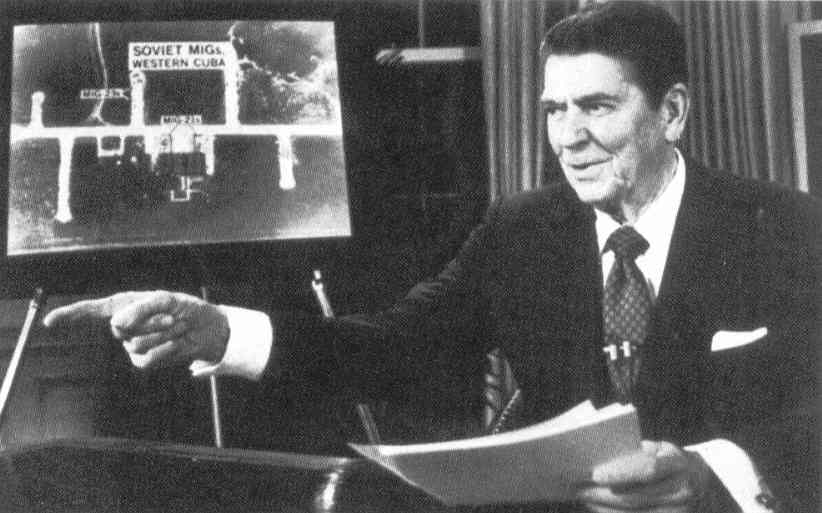

Reagan listening to the

mujahidin's

description of Soviet atrocities in Afghanistan – February 1983

Texas Congressman Charlie

Wilson in Afghanistan

Wilson was a prime mover

in Operation Cyclone, in which the US sent $ millions to support the

mujahidin in their fight against the

Soviets (unfortunately much of the money ended up in corrupt Pakistani

military hands). Resistance by conservative

Muslim mujahidin however is grinding down the Soviet effort to maintain Communist control

in Afghanistan.

|

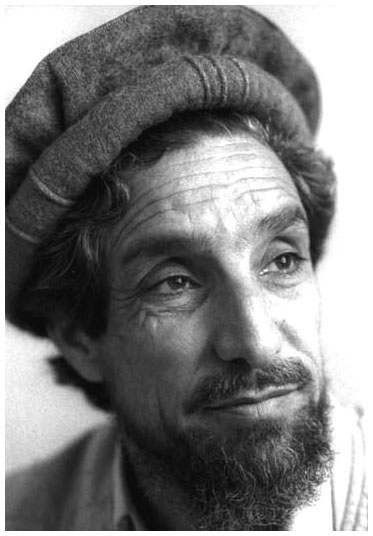

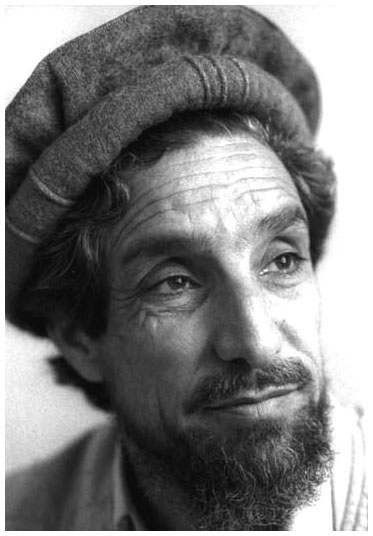

Ahmad Shah Massoud – the

"Lion of Panjshir"

|

This

engineer-turned-mujahidin

proved to the the most effective of the Afghan resistance commanders. When the Taliban later

took over the country, he became their prime opponent. The Taliban

assassinated him just days before the September 11, 2001 attack

on the New York Twin

Towers)

|

Well armed mujahedin

confronting

Soviet troops in Afghanistan

The new Soviet leader Gorbachev was pushing for a new face

to Communism

with the policies of perestroika (economic reform), glasnost (personal freedom),

and demokratizatsiya (democratization).

A Russian practicing

glasnost

on a Russian street

Gorbachev welcomed in Prague

for his reforms

Soviet Premier Gorbachev

meets with French President Mitterrand in Paris – 1985

Reagan and Gorbachev at the

first Summit in Geneva, Switzerland – 19 November 1985

Gorbachev and Reagan meet

in Reykjavik, Iceland – autumn 1986

"Mr. Gorbachev, tear down

this wall!" – June 1987

Gorbachev, realizing that the Afghan War was merely weakening further the Soviet strategic

position globally, decides to call it quits in Afghanistan – July 1987

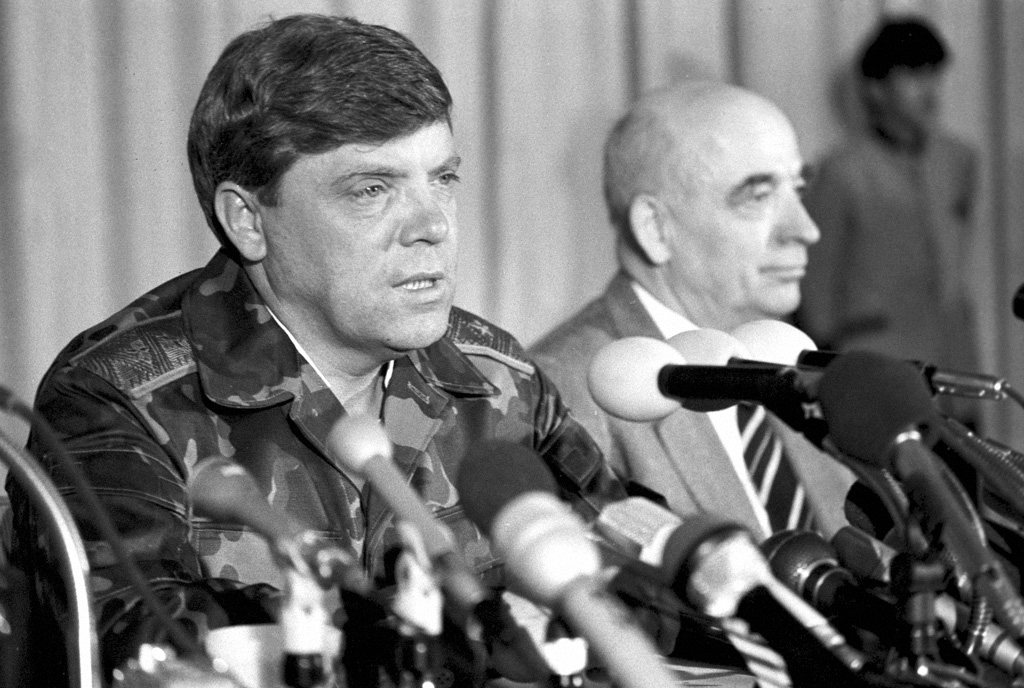

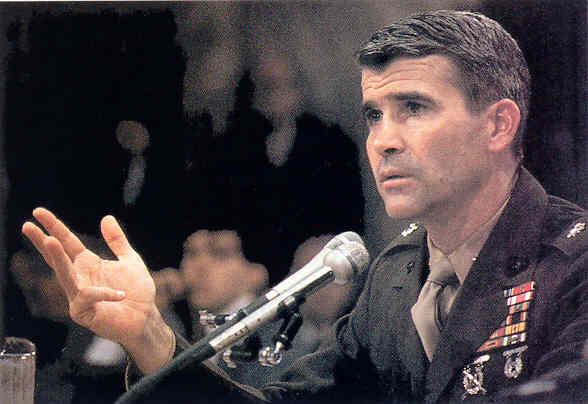

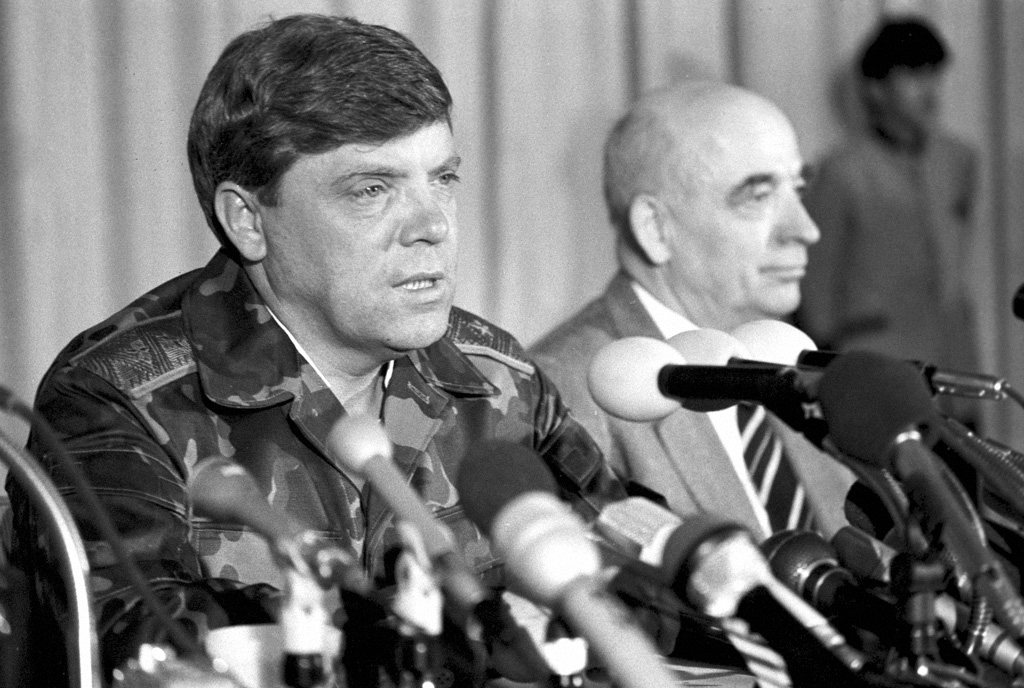

Soviet Commander Boris Gromov

announcing the Soviet troop pullout from Afghanistan – July

1987

Afghan troops (on the left)

watching Soviet troops leaving Afghanistan – 1988

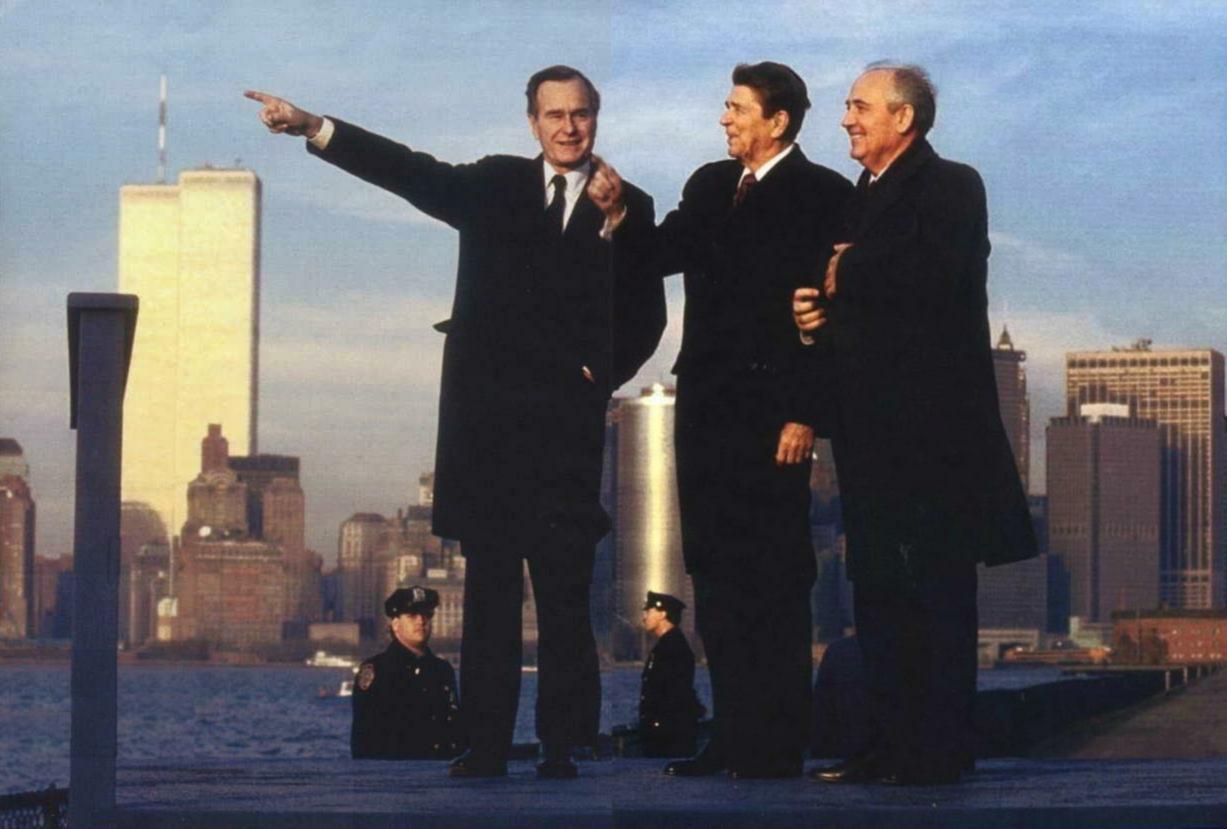

Gorbachev with Reagan on

a summit visit to Washington – 1987

The Gorbachevs visit the

Reagans in Washington – December 1987

Gorbachev and Reagan sign

the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in Washington – 1987

A Soviet sentry guarding

ICBMs scrapped under a 1987 disarmament treaty with the US

Gorbachev and Reagan in Moscow

- 1988

President Ronald Reagan visiting

with Soviet Premier Mickail Gorbachev in Moscow,

chatting in front of St.

Basil's Cathedral on Red Square

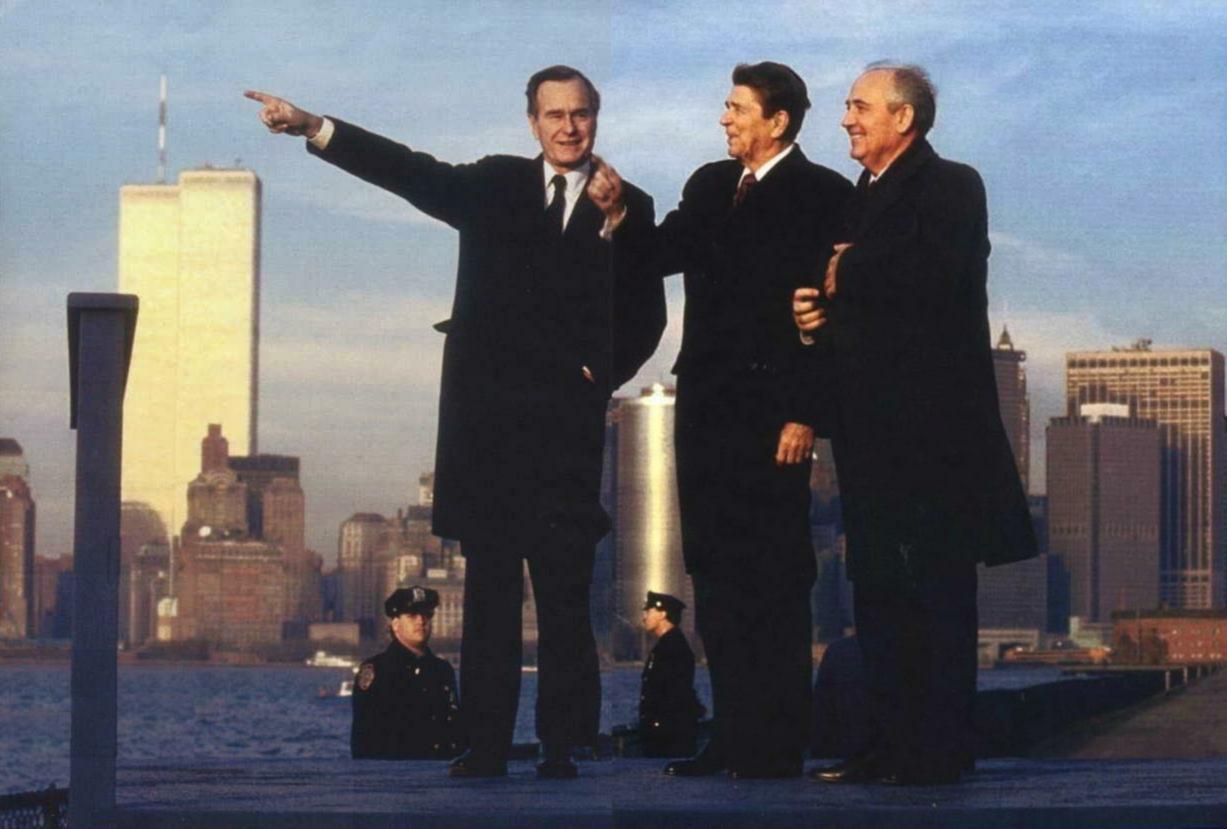

Soviet Premier Gorbachev

visiting Reagan and Bush in New York

shortly after the latter's

electoral victory in 1988

Troubles in the Middle East

Troubles in the Middle East

The

Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull down the Reagan presidency

The

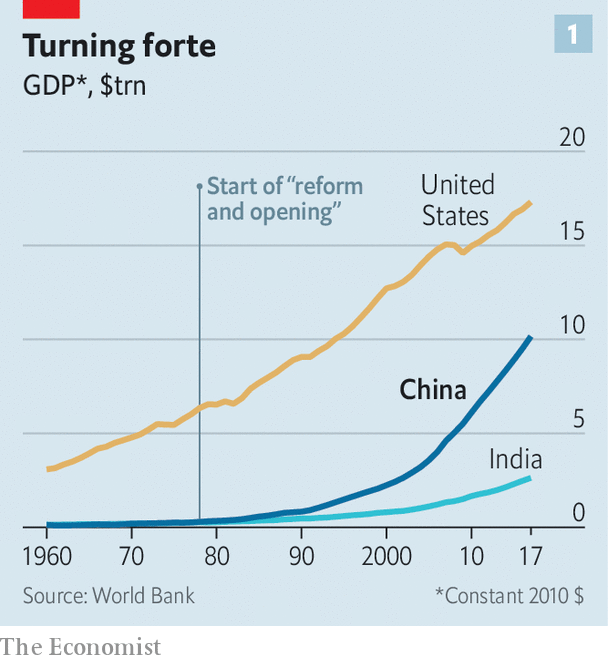

Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull down the Reagan presidency China begins to self-reform under Deng Xiaoping

China begins to self-reform under Deng Xiaoping The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire

The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire Another

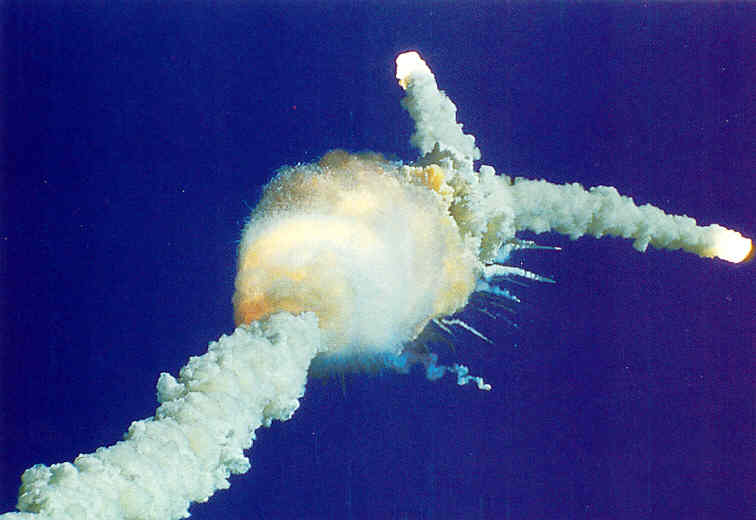

event adds a strong touch of tragedy to the Reagan years

Another

event adds a strong touch of tragedy to the Reagan years

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges