|

Iraq and the Political Idealism of the "Neocons"

While the operation against al-Qaeda and the

Taliban had been building in Afghanistan (and Pakistan), Bush's

thoughts had never been far away from the perceived dangers coming from

Iraq and its dictator, Saddam Hussein. Indeed, one of the things that

marked the Bush presidency from its earliest days was the great

antipathy that the Bush White House had to Saddam Hussein, and its

determination to remove Saddam from power. Pushing this idea strongly

was the formidable neoconservative (or "neocon") team of Donald

Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney and Rumsfeld's Assistant Defense Secretary Paul

Wolfowitz. But Bush himself was also largely in line with this point of

view.

The neocons represented the old

tradition of Democratic Idealism, but a hawkish Idealism pushed by

all-out force rather than by the dovish Idealism promoted through

diplomatic appeasement. According to neo-con thinking, Saddam was a

dictator, an evil dictator, and he needed to go. With his disappearance

the Iraqis would have a wonderful opportunity to come to Democracy on

their own. And this Iraqi Democracy would stand in stark contrast to

the repressive Arab regimes that surrounded it. Iraq would become a

beacon of democracy offering hope to the rest of the Arab or Muslim

world. This fit well with Bush's concept of compassionate conservatism.

A strongly compassionate neoconservative stand on behalf of global

democracy was the very thing that supposedly dignified America. It had

long been (at least since the days of Woodrow Wilson a century earlier)

a key part of America's "compassion" with respect to the rest of

mankind. And thus the title "compassionate neoconservative" was a name

that these White House neo-cons intended to wear proudly.

With the events of 9/11, the neocon team

jumped at what they saw was the opportunity to connect Saddam with the

terrorist attack. In accordance with the new Bush Doctrine, any country

(except obviously Pakistan!) giving sanctuary or aiding in any way the

terrorists of 9/11 the Bush White House in its War or Terror was bound

to take down. Obviously (obvious to Bush and the neocons, anyway)

Saddam must have been guilty of at least such support ... placing

Saddam into the category of "terrorist enemy." The neocons felt that

they finally had in this anti-terrorist logic all the justification

they needed to go after Saddam.

Disagreements within the Cabinet

However, CIA chief George Tenet,

Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Advisor

Condoleeza Rice were very hesitant about going after Saddam. To their

understanding, the war in Afghanistan against al-Qaeda had to take

precedence over any attack on Iraq to remove Saddam; there was little

evidence that Saddam was connected with the 9/11 events; and failing to

be able to demonstrate such a connection, America would not likely get

the support from its allies that it would need to conduct effectively

an attack on Saddam in Iraq. And there was always the question of what

to do with Iraq if and when Saddam fell.

Cheney had quite conveniently forgotten

about his 1994 "quagmire" comment concerning Iraq, an earlier insight

resulting from his having served Bush Sr. as Secretary of Defense. But

Tenet, Powell and Rice still saw Iraq in that very same light. To go

crashing into Iraq to overthrow the Saddam regime and put in place

there a "democracy" was guaranteed to throw America into a quicksand of

chaos, which would prove immensely expensive to then try to bring some

degree of order there, and for which America itself would ultimately

derive no visible benefit.

But that kind of insight was lost to Bush and the neocons, who were determined to go anyway.

Thus in his State of the Union address in

January of 2002 Bush drew Iraq into his list of America's enemies in

their "War on Terror" by describing an "Axis of Evil" of North Korea,

Iran and Iraq, constituting a growing threat to the world. Then too,

the question of Saddam's role in this War on Terror would frequently be

brought up at press conferences. Clearly the War on Terror had not only

bin Laden and al-Qaeda in its gun sights, but also Saddam Hussein.

Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs)

However, as time went on and it

increasingly appeared that there was no way to connect Saddam with

9/11, a new approach to the Saddam question began to be looked at with

greater interest by the Bush cabinet. Saddam boasted a lot about his

contempt for the UN's restrictions and sanctions concerning biological

and chemical weapons that he was supposed to get rid of, and of nuclear

development that was forbidden to Iraq. Boasting was one of the ways

that Saddam attempted to keep a tight lid on Iraqi politics and a firm

grip over the various ethnic sub-communities that made up Iraq. Such

boasting however gave the neocons the "proof" they needed that Saddam

was indeed developing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), in violation

of a number of U.N. resolutions. Therefore, America now clearly had

moral grounds for taking action against Saddam – or so they hoped.

But here too, to get the international

community behind such a move, Bush would need some kind of direct

testimony from Iraqis themselves concerning Saddam's criminal

activities. Besides the Saddam boasting, all that they had was the

testimony of a group of Iraqi expatriates who called themselves the

Iraqi National Congress (INC) – who had gathered around the leadership

of Ahmed Chalabi. Chalabi had a deep hatred for Saddam, in great part

because of Saddam's horrible persecution of the Iraqi Shi'ites,

(Chalabi was a Shi'ite).

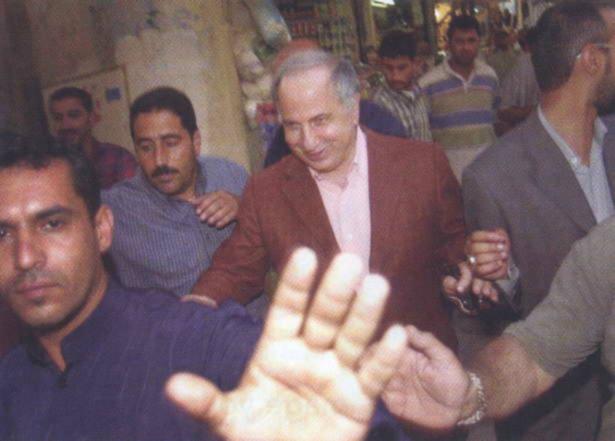

As an expatriate mathematician (with a

Ph.D. in mathematics) and businessman living in the West since 1956,

Chalabi had cultivated politicians in Washington (including the

neocons Rumsfeld, Cheney and Wolfowitz) who believed that he could be

the very person to replace Saddam, should the dictator fall. But

Chalabi's personal background was troubling. Some CIA reports indicated

that he could not be exactly trusted at his word – and that he might

even be a double agent working with the radically Shi'ite Iranian

(Islamic Republic) government. Powell's State Department did not trust

him either, finding no support for him, or even knowledge of him, in

Iraq – and also wondering what happened with all the money that had

been handed to him to support the INC.

But Rumsfeld and Cheney paid more

attention to Chalabi's claim to have knowledge of the development of

WMDs going on in Saddam's Iraq than they did to the hesitations of the

CIA and State. Chalabi had given them exactly what the neocons wanted

to hear.

Taking the case to the World

Powell however was balking at the neo-con

position, which he felt was moving faster than the rest of America's

allies were ready to move. He was afraid of a developing

"unilateralism" on this matter ("forget the rest of the world; we can

do this ourselves if need be"). Powell would get much appreciated

support for his position when British Prime Minister Tony Blair arrived

in Washington. Blair made it clear that Britain would gladly support an

anti-Saddam action – but only if it got U.N. approval for action. That

of course would require well-demonstrated violations by Saddam of the

restrictions placed on him by the U.N.

And so on September 12, 2002 (almost

exactly one year after the 9/11 event) Bush went before the United

Nations to lay his case for the necessity of an invasion of Iraq to

depose Saddam. He listed WMDs as the danger that faced the world if it

did not act with the U.S. in deposing this dictator.

But some of America's traditionally

strongest allies, France, Germany, Canada and New Zealand had strong

reservations about the matter. They viewed the anti-Saddam move as a

distraction from the real business at hand in Afghanistan. They worried

about what would happen to Iraq if Saddam were suddenly removed from

the political scene. Then there was also the major principle that would

be violated in invading another country without major compelling

reasons. Saddam was a nuisance. But a threat to the world necessitating

his and his government's elimination? Where was the American case for

that? Where was the hard evidence that pointed to the need for the kind

of action that the Americans were requesting?

Finally in November, the U.N. Security

Council arrived at a compromise (Resolution 1441) which called for

renewed inspections by a U.N. inspections team – and the threat of

"serious consequences" if Saddam did not accept this decision. But both

Russia and France let Bush know that "serious consequences" was not to

be automatically interpreted as the right of America to invade Iraq.

And so the U.N. inspectors were sent off to Iraq to search for WMDs. It

was not exactly what Bush wanted. But it was a start.

Bringing Congress on Board Concerning Iraq

Now it was time to get Congress's

backing. Bush put before Congress in October a request for a resolution

authorizing the use of U.S. armed forces against Iraq. At this point

Tenet was brought before the Senate to testify about what the CIA had

to say about the situation. But he confessed that the CIA had no

intelligence estimate (study or report) on Iraqi WMDs! The Senators

were astonished. Here the White House was clearly trying to move the

country toward some kind of military engagement against the Iraqi

government – and the CIA had no information to offer on the subject?

Tenet confessed that the Agency was busy in Afghanistan and had not

found the time to do a study on the subject! Actually, Tenet knew that

the CIA had no firm data to back up the White House's WMD claims and

was trying to skirt the subject. But the Senate insisted that he come

up immediately (within two weeks) with a complete Iraqi estimate.

Meanwhile Rumsfeld's Pentagon

intelligence service (the Defense Intelligence Agency or DIA) came up

with its own "smoking gun" evidence: proof that the African country

Niger had sold yellow cake uranium to Saddam. Saddam, according to the

DIA, was indeed working on nuclear energy development in violation of

all U.N. resolutions – with the clear intent of developing a nuclear

bomb. This and other documents had been sent on to the CIA and other

intelligence services by the Italian intelligence service – but had

been dismissed by the CIA as likely forgeries. But then the DIA

published its own intelligence assessment describing the yellow cake

sales and also the discovery of some aluminum tubes designed to be used

in centrifuges employed in enriching uranium. The CIA had been upstaged

by Rumsfeld's DIA.

At this point Tenet did what no true

intelligence officer should ever do, which is to come up with the

"facts" that he knows others want to hear. But that is exactly what he

did. Rumors of aluminum tubes that were part of nuclear development

that had been spotted in Iraq and mobile truck units possibly carrying

biological weapons were now certified as being more than rumors but

indeed hard fact (which Tenet knew was not the case). The sure and

certain existence of WMDs in Iraq now become the official stand of

Tenet. He had fallen in line with the neocons Rumsfeld, Cheney and

Wolfowitz.

And thus Congress on October 16th gave Bush the much-wanted

authorization to go to war against Saddam. It was just weeks before a

Congressional election and few Congressman, not even the Democrats,

were eager to appear to go on record as being opposed to a war against

a known evil dictator. The support was overwhelmingly in favor: 297 for

(215 Republicans and 81 Democrats) and 133 against (6 Republicans, 126

Democrats and 1 Independent) in the House and 77 for (48 Republicans

and 29 Democrats) and 23 against (only 1 Republican, 21 Democrats and 1

Independent) in the Senate.

Trouble Getting the World on Board

However, the harder Bush tried to make a

case, the harder some of America's allies, most importantly France,

worked to head off the move that Bush was clearly intent on making. The

situation for America was not being helped any by reports from the U.N.

inspectors in early 2003 that so far, their search had revealed no

WMDs. They had discovered some materials and problem areas in Iraqi

reporting. Saddam was not being cooperative. But the inspectors

themselves had nothing yet that pointed to actual WMD production or

even possession.

By now heavy pressure was being exerted

on Powell as Secretary of State not only to be brought into the Cabinet

"circle of the willing," but to stake his unimpeachably high

international reputation in going before the world community to explain

the American case in a final effort to get our allies on board with us.

The event that finally got Powell on board was an inexcusably rude

treatment of Powell by the French Foreign Minister Dominique de

Villepin. Powell was now ready to go.

On February 6, 2003, Powell went before

the U.N. Security Council – complete with photos, drawings and

illustrations of what U.S. intelligence had "confirmed" as pointing to

WMDs. He also tried to draw a connection between Saddam and al-Qaeda

claiming the existence of a training camp in Iraq under al-Qaeda

operative Zarqawi. The tragedy was that none of this information that

had been passed on to Powell to present at the U.N. had been verified

by normal intelligence gathering standards. Almost all of it would soon

prove itself to have been either totally false or simply hyped in order

to achieve the desired effect. But in any case, the presentation did

not move Russia, China, France or Germany away from their strong

skepticism, even growing opposition, about the American program. A week

later the U.N. inspectors' chief reported that the Iraqis were becoming

more cooperative – and that there were serious problems with a number

of Powell's assertions.

In fact outside of America, the support

for America's attack on Iraq was quite weak. On February 15 an

internationally organized anti-war protest turned out somewhere between

six to ten million people in approximately 800 cities around the world.

Even in Britain itself, where the Blair government was supportive of

America, clearly the British people were not. Tragically for Blair, the

Iraqi war in fact would prove to be the political undoing of a British

prime minister who up until then had one of the highest popularity

ratings ever with his people.

Nonetheless, toward the end of February,

America, with its allies Britain and Spain, presented the proposal for

a new U.N. resolution certifying that Saddam had not cooperated fully

under the terms of Resolution 1441. Thus, as America saw things, it was

time to kick into gear the "serious consequences" portion of 1441.

Passage of this new resolution would have given some kind of support to

American actions in Iraq. But it became apparent that the proposal was

supported only by its three sponsors plus Bulgaria. France, Russia and

Germany were strongly opposed. Seeing that failure in a vote would be

worse than no vote, the proposal was withdrawn. These were not good

signs for Bush.

|

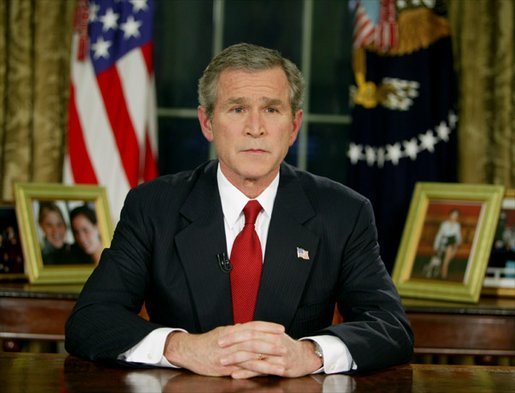

The

idea of extending the "Bush Doctrine" to Saddam Hussein

The

idea of extending the "Bush Doctrine" to Saddam Hussein

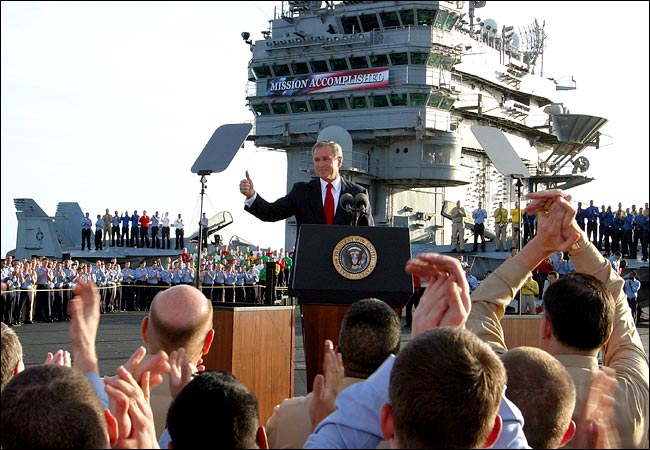

Bush

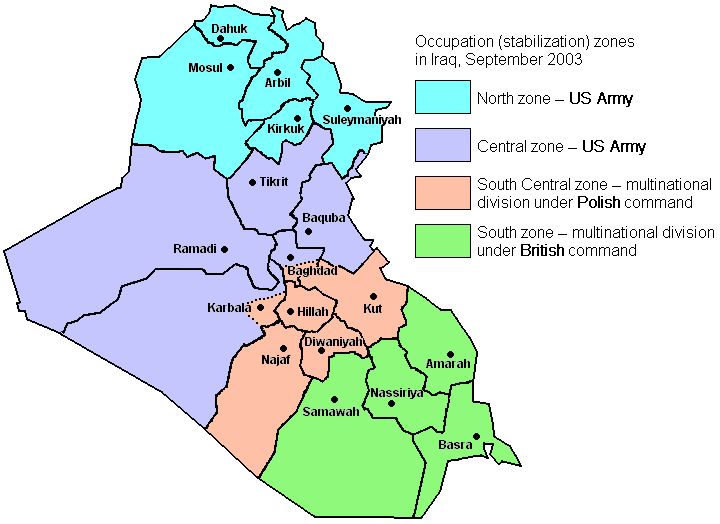

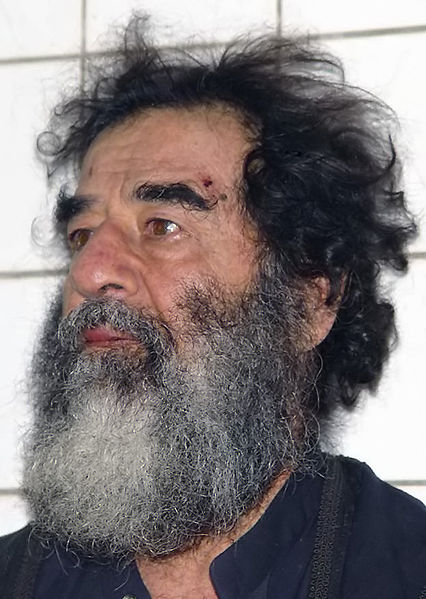

decides that it is time for Saddam Hussein to go – April 2003

Bush

decides that it is time for Saddam Hussein to go – April 2003

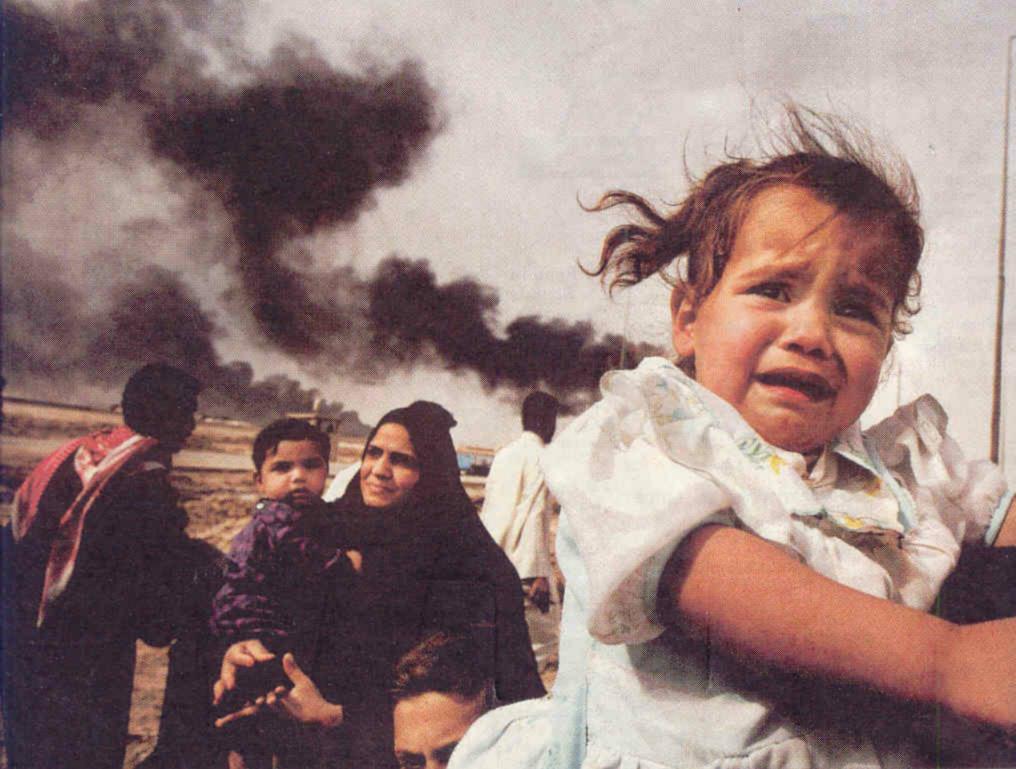

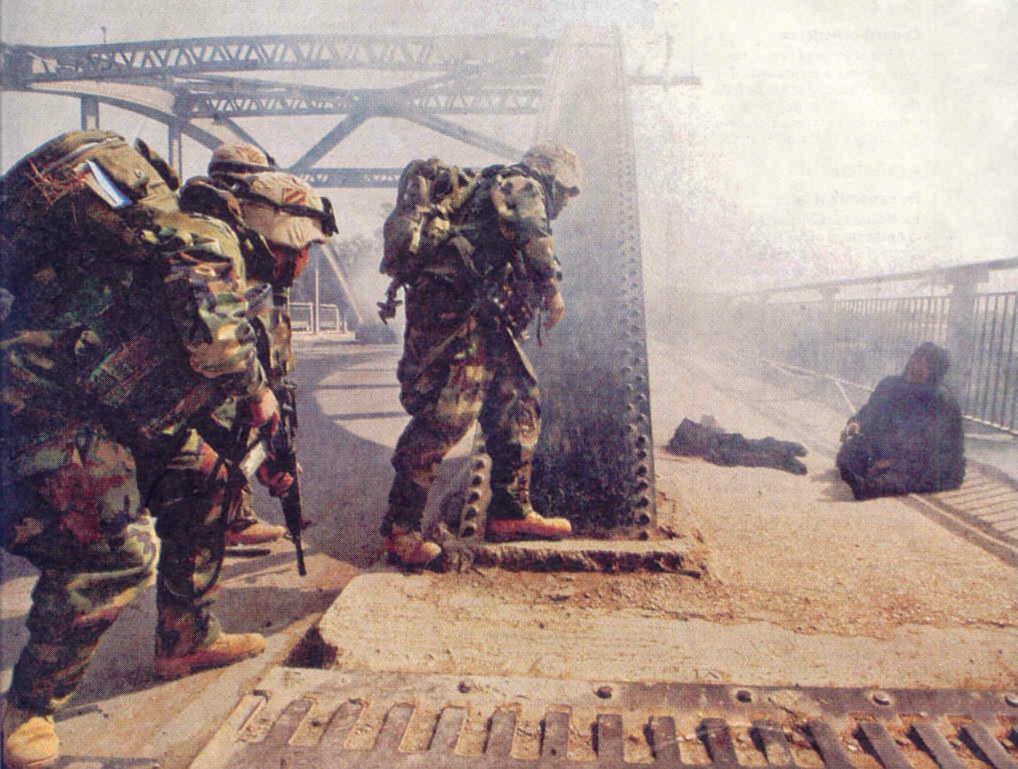

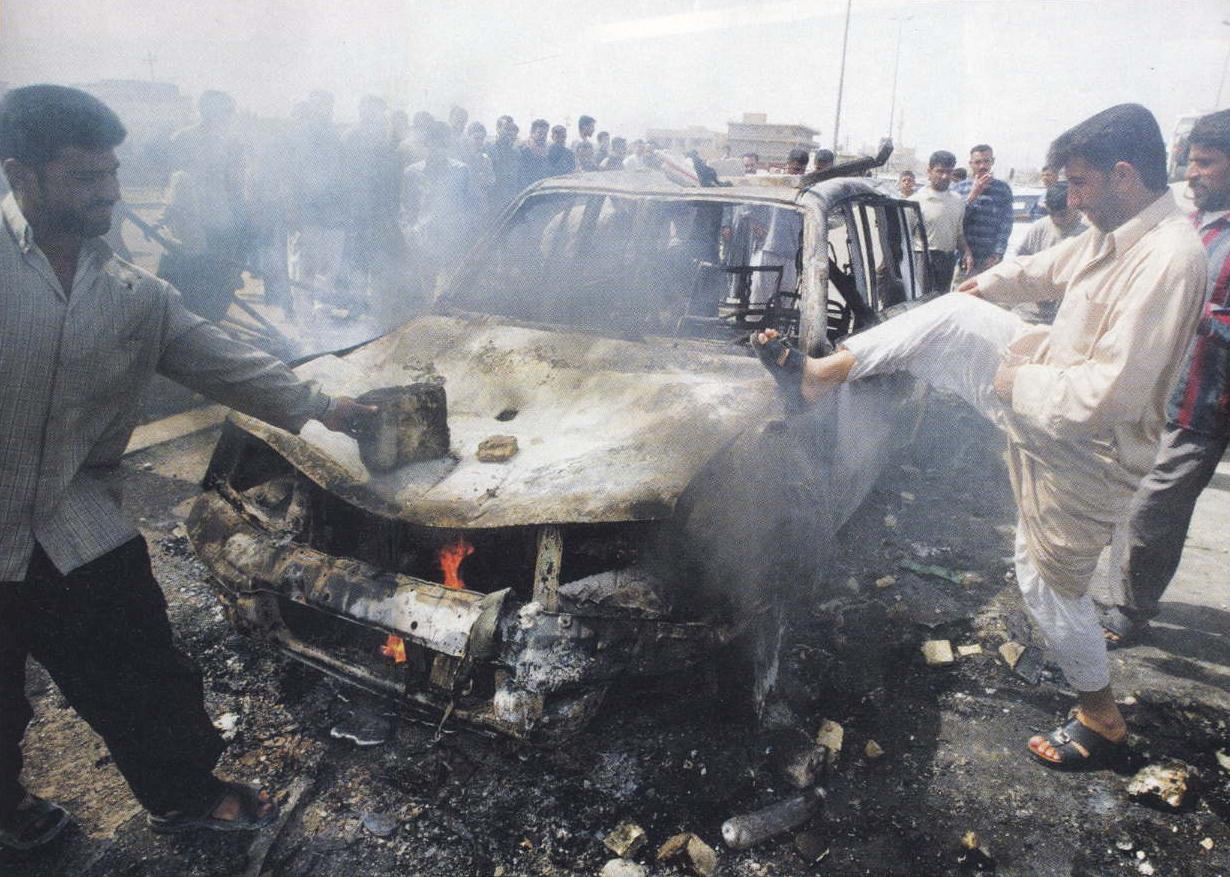

Things

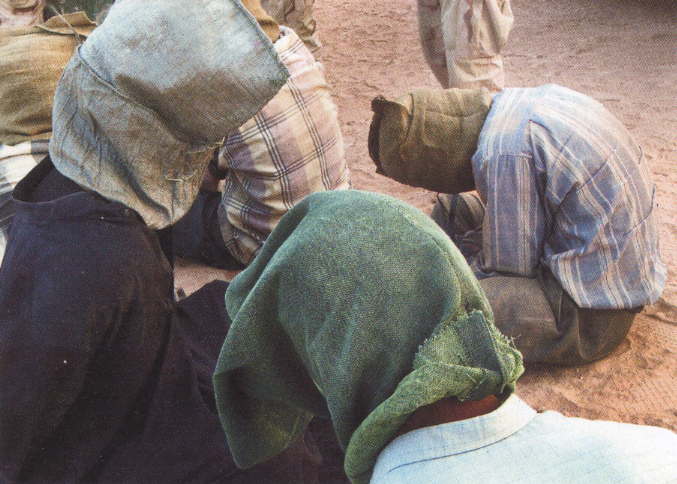

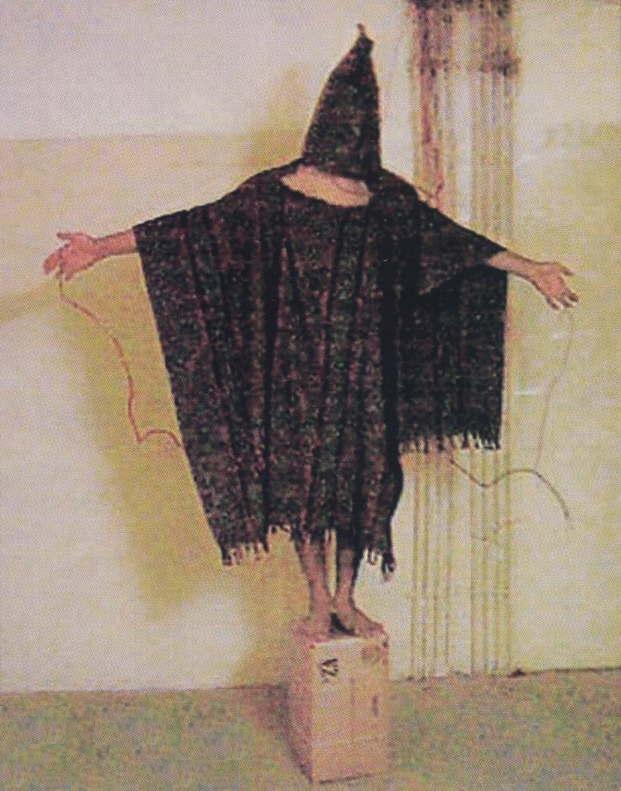

begin to bog down for the U.S. in Iraq

Things

begin to bog down for the U.S. in Iraq

2004:

The situation in Iraq worsens

2004:

The situation in Iraq worsens

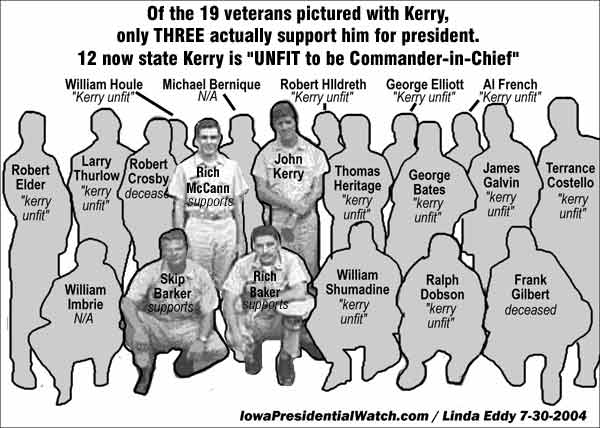

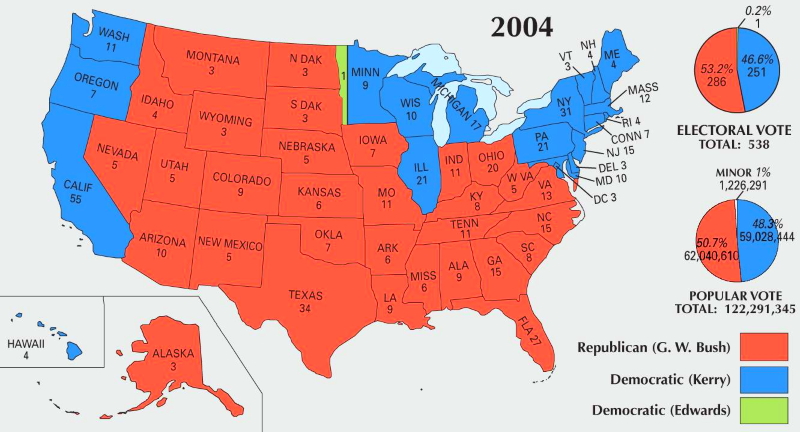

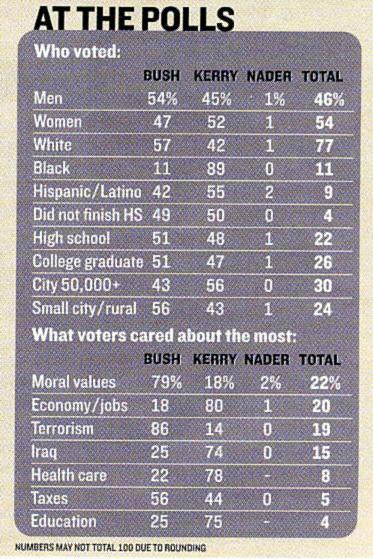

The 2004 presidential election

The 2004 presidential election

The situation continues to deteriorate in Iraq

The situation continues to deteriorate in Iraq The 2007 "troop surge"

The 2007 "troop surge"

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges