Two of the biggest banks in the mortgage market

(holding about half of the mortgages on American homes) were actually

set up by the federal government to aid homeowners in securing

mortgages. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) was

created by President Roosevelt as part of his New Deal during the Great

Depression of the 1930s. The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation

(Freddie Mac) was established in 1970 to facilitate the buying and

selling of mortgages on the secondary market, freeing up money for

banks to be able to make mortgages more readily available to home

purchasers. Contrary to what is commonly believed, these are not

government-owned corporations; they are not (or were not) even

government-backed corporations. They are Government-Sponsored

Enterprises (GSEs) only. Ownership belongs to private investors, just

as with any other corporation. However, many people (including foreign

investors) invested in these corporations believing that they had the

full backing of the U.S. Treasury. As many would soon discover, this

was not the case, at least not originally.

Both GSEs had ventured deeply into the

subprime, Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) market to keep their earnings

at the level they had been enjoying when the housing market first

heated up in the late 1990s. This all looked very good on paper. But

the fact is that by 2005-2006 both organizations found themselves

hugely overextended. By mid-2007 both of these huge mortgage companies

were in serious trouble.

By late 2007 there were clear signs that

the economy was slowing. The White House decided that what the economy

needed was some economic "stimulus" in the form of new tax breaks for

businesses and large tax rebates for American families (the Economic

Stimulus Act of 2008). In late January and early February Congress

authorized approximately $150 billion in such tax rebates. By late

spring of 2008 the benefits were out, and the economy picked up

(somewhat). But beneath it all was a waiting catastrophe.

The first signs of the looming

catastrophe came with the news that the huge investment bank, Bear

Stearns, was in deep trouble. It was terribly overextended in the

mortgage market, leveraged with debt it had accumulated to invest in

the wildly speculative housing market (it had borrowed about 30 times

as much as it had in real capital). White House economists scrambled to

find a buyer for the company. JP Morgan agreed to the deal, as long as

the government would lend $30 billion to cover the unwanted mortgages

portion of the deal. The company was saved, and a panic on Wall Street

was avoided, for a few months.

Meanwhile, attempts had been made in

previous years by the White House to reign in the speculation of the

two GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; but Democrats resisted these

efforts, defending these organizations as the hope of the little man.

But by mid-2008 the catastrophe hanging over both organizations was

obvious to all. Panic had set in among the mortgage speculators and

both GSEs were facing total collapse. In July, both organizations were

put under tight regulation, and the Federal Reserve was authorized to

step in to offer low interest rate loans to both organizations in an

attempt to restore confidence in them. But the crisis was too big. By

August of 2008 both organizations had lost 90 percent of their stock

values (as compared to their value the previous year). In early

September the government (the U.S. Treasury) had to step in to bail out

both institutions, to the tune of $100 billion of taxpayers' dollars

committed to each of these two institutions in order to get them back

on their feet. These were now in large part (temporarily, it was hoped)

government-owned. The bail-out saved the organizations, but seemed to

have little effect in stopping the panic. Investors were now scared

that other corporations that were over-leveraged in the subprime

mortgage markets were also facing failure.

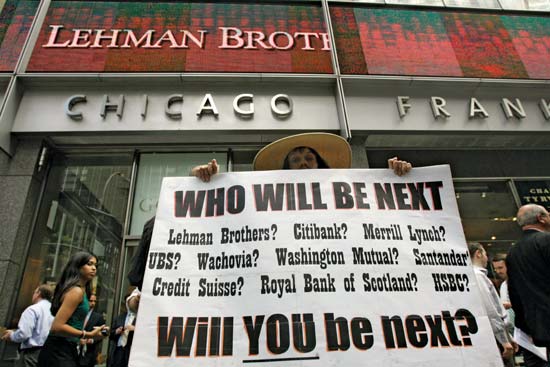

By the weekend of September 13-14, the

panic was spreading as a major meltdown of the world of investment

banking. The panic hit the huge Lehman Brothers investment bank,

enormously overextended in the wild investment game. It was so

leveraged with its paper assets that it took only a 3 to 4 percent

decline in the value of those assets to collapse this prestigious firm.

But unlike Bear Stearns, no single purchaser could be found for this

long-established investment bank. On the following Monday the company

was forced to file the largest bankruptcy protection in American

history. The consequences were that this huge company had to be carved

up into pieces and sold to various other investment banks abroad,

principally Barclays of London.

The meltdown of the Lehman Brothers so

panicked Wall Street that the last two unregulated investment banks,

Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, whose own stock plummeted

dramatically in September, moved quickly to convert themselves into

traditional banks under the regulation of the Federal Reserve. However,

the famous investment banking and stock brokering firm Merrill Lynch

did not fare as well in the face of its own huge losses, and was

rescued from total catastrophe only when the Bank of America bought out

the company at a bargain basement price. But Washington Mutual,

America's largest savings and loan association, was not this fortunate.

After a 10-day run of people withdrawing their deposits from the bank,

it was taken over by the FDIC (the federal agency which insures

people's bank deposits), its banking subsidiary sold off cheaply to JP

Morgan and the holding company placed in Chapter 11 bankruptcy

protection. This panicked depositors and investors in the Wachovia

bank, the fourth largest American bank. It too was taken over by the

FDIC, and was eventually acquired by Wells Fargo Bank (with Citibank

competing for the purchase) as a joint banking merger.

Meanwhile the largest American insurance

company, American International Group (AIG), nearly self-destructed

when, because of a loss of $18 billion (mostly in the subprime mortgage

market), its credit rating was downgraded. This in turn caused a

panicked sell-off of its stock, to a point where the stock was traded

at only $1.25 a share – down from $70 a share the previous year! Again,

attempts were made to find a buyer for the company. But AIG was too

big. The Federal Reserve stepped in on September 18th to save the

company from extinction by offering a $85 billion taxpayer-funded

government bailout (that amount would be increased by the next year to

a total of over $180 billion). The net result was that the U.S.

government ended up owning (again, presumably only temporarily) 80

percent of this huge insurance company. This put an end to the panic.

But AIG subsequently was forced to sell off many of its subsidiaries in

order to begin to pay down that debt

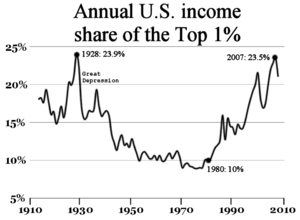

The

growing national debt crisis and American trade imbalance

The

growing national debt crisis and American trade imbalance The

growing income inequality in America

The

growing income inequality in America

The

September 2008 financial meltdown

The

September 2008 financial meltdown

TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the troubled firms (October 2008)

TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the troubled firms (October 2008)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges