|

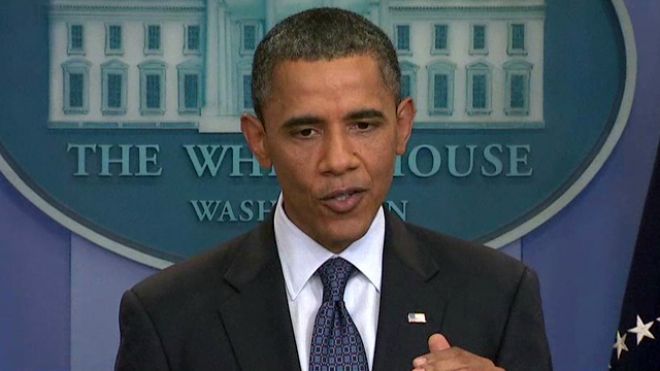

The American economy in trouble

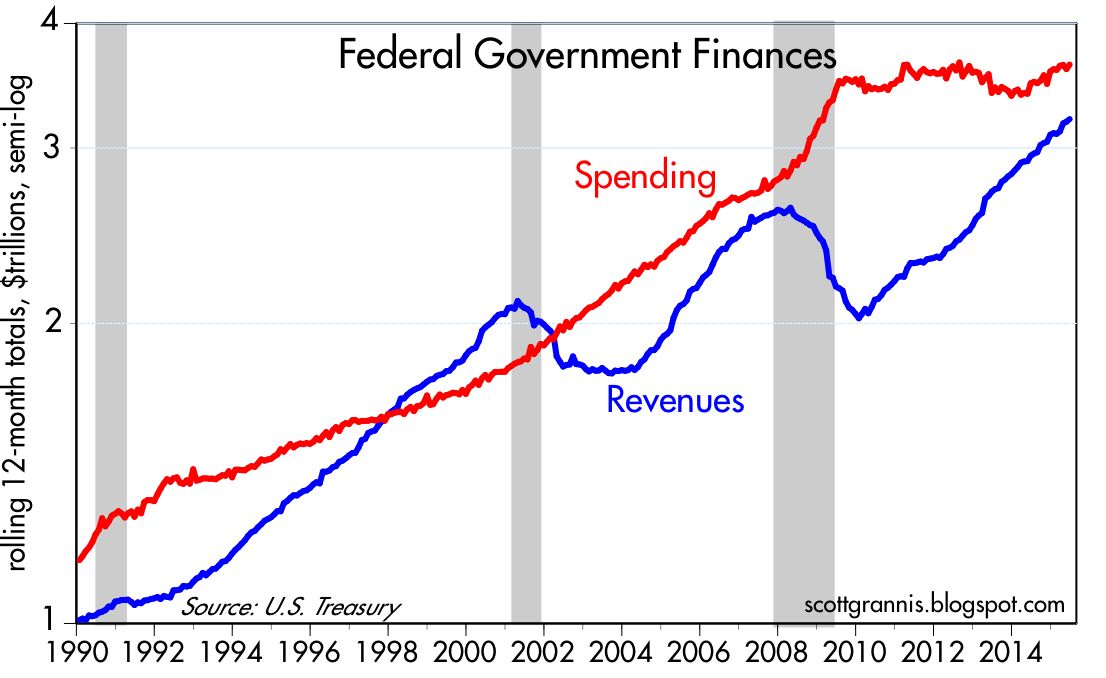

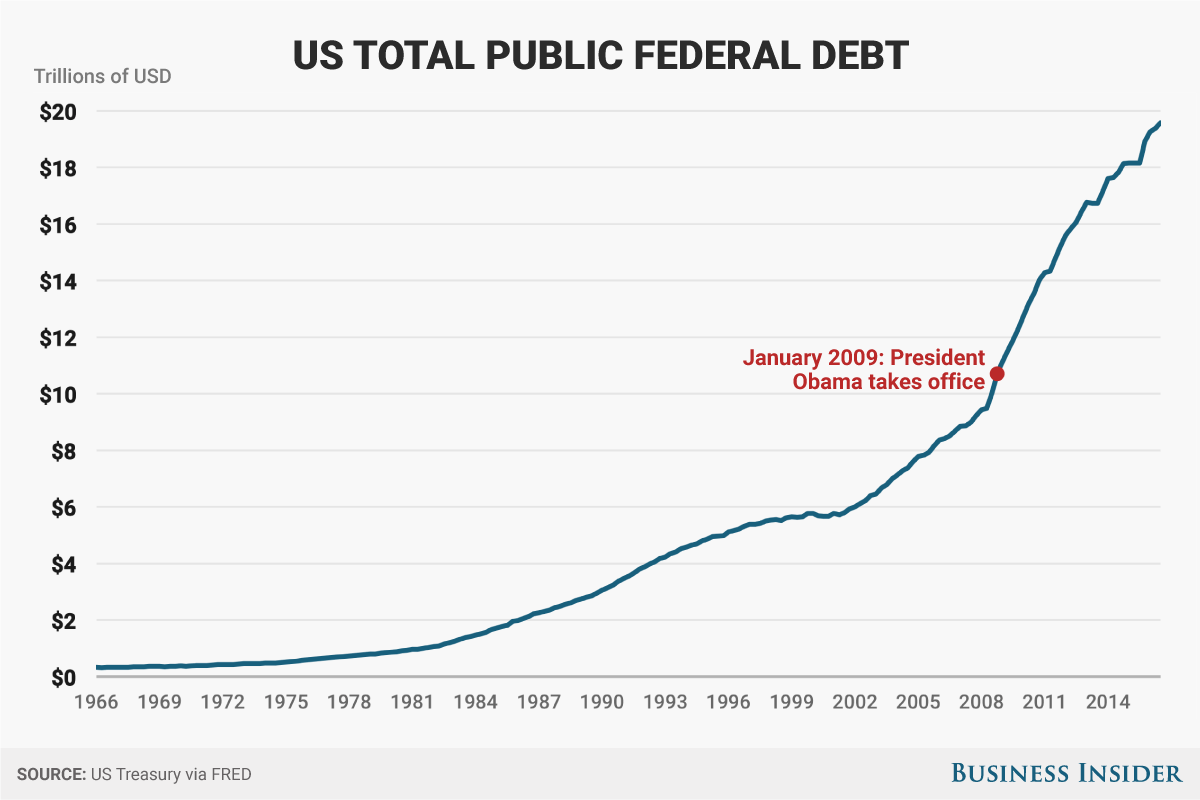

However, for the

time being, the biggest or most immediately pressing issue facing Obama

as he took office in January of 2009 was the nation's economy. The

public debt was approximately $10 trillion, the banks – despite the

huge governmental bailout – were not by any means out of trouble, the

Big Three American auto manufactures were still in deep trouble, and

the economy in general seemed stalled, if not slipping back.

An additional $787 billion in "stimulus"

funding. Obama, immediately upon assuming the presidency, began to move

forward on the assumption that by this time had become holy writ: when

the economy slumps, it is the duty of the government to step into the

economy to stimulate it back to health with government spending

programs (if a Democrat) or tax reductions (if a Republican). Either

way this is supposed to put more money into the hands of the Americans

who then can spend the economy back to health.

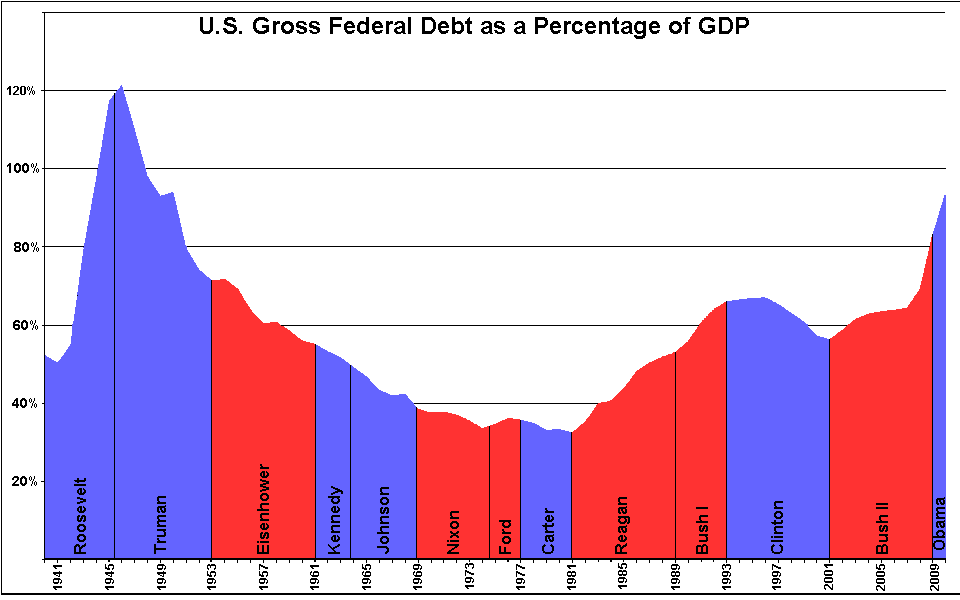

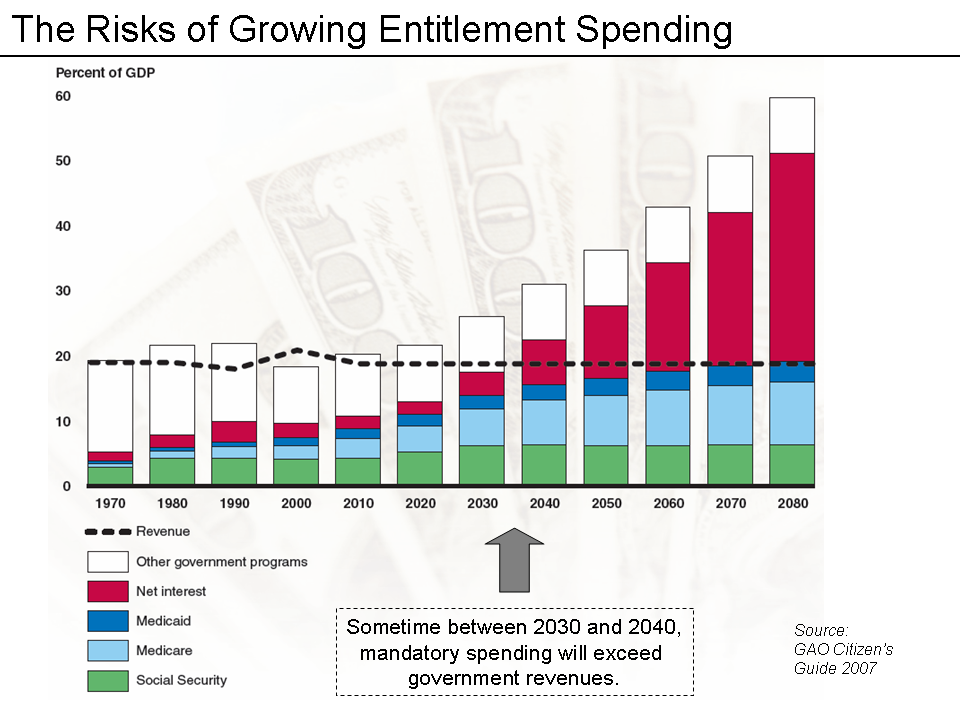

But either way, it also puts the

government deeper into debt. But supposedly this is only a temporary

measure; when the economy picks back up the government is supposed to

cut back on its spending or raise taxes back up, or both. But

historically this seldom happens, or does so only marginally.

Upon coming to office Obama immediately

put forward before Congress a proposed American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act, a $787 billion wide-ranging economic stimulus

package, which included federal spending for expanded unemployment

benefits, health care, green energy, education, infrastructure

development and various job creation programs. This was in addition to

the $700 billion recovery program put into effect by Bush during his

last days in the presidency.

Republicans balked at the new measure,

seeing this not merely as a way to put more money back into the

economy, but a sure and certain path to a state-managed economy or

"Socialism." But with a Democratic majority in both houses of Congress,

approval of Obama's stimulus package was quite certain. In late January

the measure passed 244-188 in the House, in an almost perfect

Democrat-Republican split, and in early February 61-37 in the Senate,

also almost completely along Democrat-Republican Party lines. Obama

signed the bill and it became law on February 17th.

The troubled auto industry

Meanwhile the situation facing the

automobile industry worsened. In mid-February both General Motors and

Chrysler came to Washington looking for $20 billion in additional

federal funding in order to stay afloat. The companies promised to slim

down by closing five plants and 50 thousand jobs and dropping 15 car models

from production. They would also shut down hundreds of local

dealerships. Then in April Chrysler filed for bankruptcy, announcing

also that the company would be entering into partnership with Italy's

Fiat corporation; Fiat would hold 20 percent of the company's stocks,

expanding to 35 percent and then 49 percent as the company rebuilt.

General Motors filed for bankruptcy at the beginning of June. As a

result, the U.S. government took 60 percent control of General Motors

and the Canadian government 12.5 percent, with the rest going mostly to

the labor unions. The original stockholders in the company were left

out in the cold.

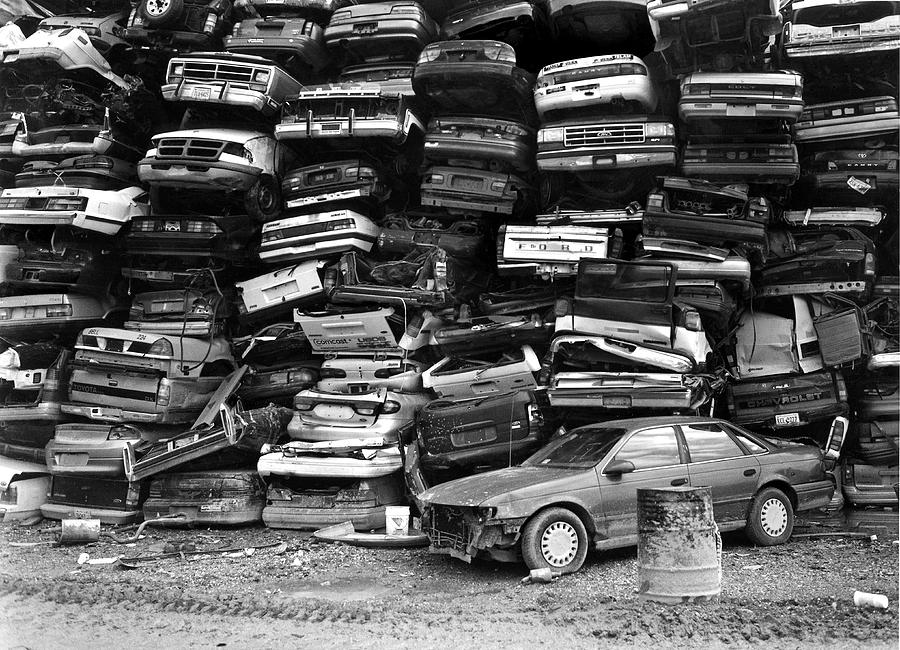

To encourage the auto industry, in June

(2009) Obama signed the Car Allowance Rebate System or "Cash for

Clunkers" which encouraged Americans to trade in their gas-guzzling

American SUVs for new, more fuel-efficient cars, offering them vouchers

to be used toward the purchase of the new cars, varying from $2500 to

$4500 depending on the amount of the fuel economy improvement in the

exchange. Cars traded in could not be resold as used cars but had to be

scrapped.

The program was to run from July to

November but ran out of the allotted $1 billion in federal funds before

the end of July. Congress subsequently extended the fund by an

additional $2 billion, which ran out by the end of August, thus finally

ending the program.

Bigger winners in the program were the

Japanese and Korean cars (the Japanese had a similar program but one

which excluded American cars), which actually increased their share of

the U.S. market.

One of the additional negative side

effects for American consumers was that the program took out of

circulation hundreds of thousands of used cars that poorer Americans

counted on buying as their personal transportation. But with Obama

supposedly being a champion of America's poor, nothing was really said

about this new hardship for the American poor caused by Obama's Cash

for Clunkers program.

Also a study later revealed that the

overall effect of the program ultimately produced a loss of $1.4

billion in car value when compared to the supposed benefits of

increased fuel efficiency.

The government's Troubled Assets Recovery

Program (TARP) initiated under Bush during his last days in the

presidency seemed to meet its objectives better than most had expected.

This was a buyout program originally limited to troubled real estate

mortgages and other troubled real estate assets, although Bush

had expanded it to include the troubled auto industry as well. The purpose

was to allow the Federal government to buy failing companies (at a

reduced stock price) rather than let them fail altogether. These

companies were then to restructure themselves to be more efficient, and

then find buyers (corporate and personal) for new stock. The long-term

expectation was that as these corporations returned to health, they

would be able to buy themselves back from the government.

As it turned out, of the $700 billion

originally authorized for the purchase of these troubled corporations

only about $300 billion was actually disbursed in the government buyout

of these corporations. Further, the corporations over the next two

years were able to buy themselves out of indebtedness to the government

by almost $175 billion. The program ended up costing far less than

expected, and the country stood to gain profitably as other companies

completed their repurchase (with interest).

There

were however some troubling issues

that accompanied TARP. One of the biggest was the use of TARP moneys to

pay the bosses of these troubled corporations the huge compensations

that they were used to getting. Obama put a cap of $500 thousand on

executive compensation, though it seems that promises were made

nonetheless to executives to reimburse them lost compensation once the

companies were back on their own feet. Similar to that was concern that

this money was being used to award dividends to preferred stockholders,

rather than buy back the warrants or obligations owed the U.S.

government.

Overall despite the rescue of a number of

American corporations from bankruptcy, and billions pumped into the

economy in the form of government spending of various programs, over

the next two years the economy registered minimal growth: negative in

2009 and only 2.5 percent increase as of September 2010. Unemployment

remained very high, rising from 9.4 percent of the working age

population in 2009 to 9.9 percent in 2010. If those with only part-time

employment and those who seem to have given up looking for work

altogether were factored into the recorded unemployment rate, that

figure would be 15.9 percent.

|

Stimulating

the economy

Stimulating

the economy

Putting

some brakes on run-away financial speculation

Putting

some brakes on run-away financial speculation

The rapidly rising federal debt

The rapidly rising federal debt

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges