15. THE "ROARING 20s"

AMERICA'S MORAL COMPASS BEGINS TO SPIN"

The big disappointment: The Interchurch

The big disappointment: The InterchurchWorld Movement

Also: traditionalist America does not

Also: traditionalist America does not

warm up to this new culture

Resisting this new culture was

Resisting this new culture was

traditional "Old Time" Christian religion

Traditional America celebrates

Traditional America celebrates

America's great traditions

Prohibition was Traditional America's

Prohibition was Traditional America's

way of opposing the New Culture

But "New America" had a way of striking

But "New America" had a way of striking

back at Traditional America

Meanwhile, American cities come under

Meanwhile, American cities come under

increasing control by the "mob"

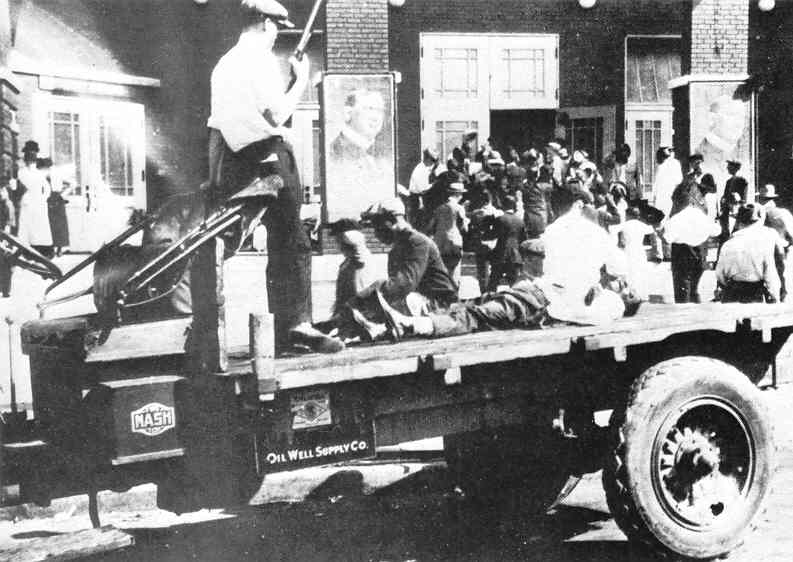

American Blacks also come under the

American Blacks also come under the

ame kind of ethnic hatred

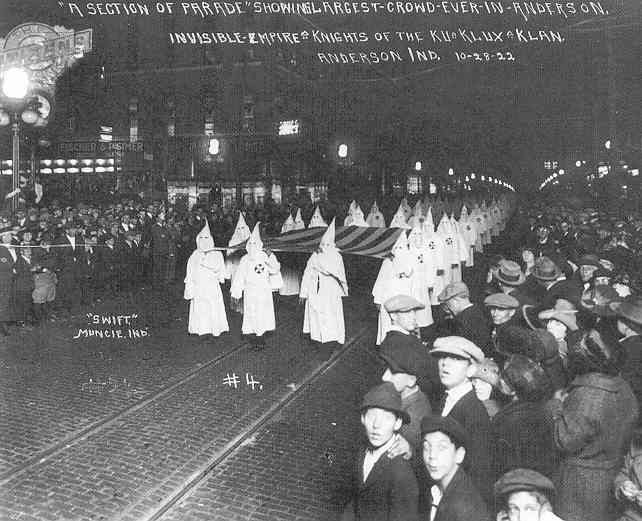

A sign of the times was the rapid growth

A sign of the times was the rapid growth

of the Ku Klux Klan

The "Scopes Monkey Trial" – Dayton,

The "Scopes Monkey Trial" – Dayton,

Tennessee – 1925

Christian Fundamentalism vs. Christian

Christian Fundamentalism vs. Christian

Liberalism

However, even in urban America,

However, even in urban America,

cynicism afflicts the "roar"

of the

"Roaring 20s"

Freudian psychology explains and

Freudian psychology explains and

justifies the American mood

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 478-490.

THE BIG DISAPPOINTMENT: THE INTERCHURCH WORLD MOVEMENT |

ALSO: TRADITIONAL, RURAL AMERICA DOES NOT WARM UP TO THIS NEW

CULTURE |

|

The onset of a deep rural depression (early 1920s)

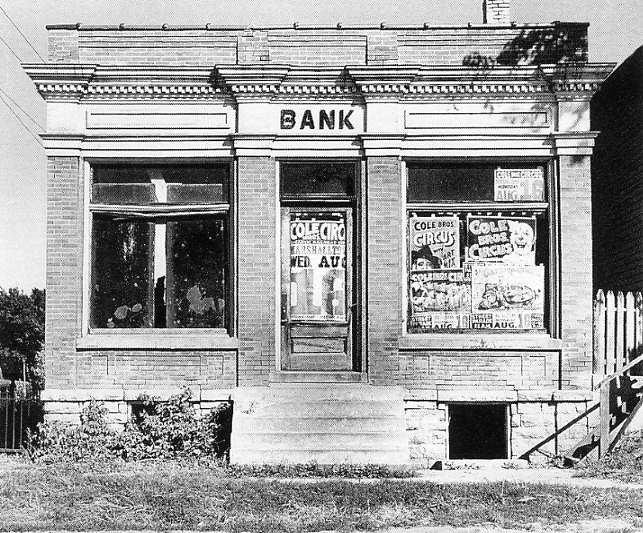

It must be noted that although the 1920s is regarded as the materialist age of the radio, the automobile, the home appliances, etc. that made American life so rich – these riches were concentrated largely in urban, and to a lesser extent in small-town America. They were largely lacking on the farms of rural America, where generally electricity had not yet reached. But that was the least of the problems faced by rural America during the 1920s. From the onset of the Great War in Europe in 1914 the demand for American farm goods skyrocketed as European farmers were taken away from their fields and put into uniform to fight in the trenches. Prices for American farm goods rose accordingly and the American farmer found himself to be something of a very successful businessman. Life was full of promise on the American farm. So, the farmer mortgaged his home and farm to buy more land – and machinery to work the land – in order to greatly expand his business. The profits rolled in – while the war lasted. Farm failures. When the Great War ended in late 1918, the good times of the American farmer ended as well. With European soldiers returning to their farms, Europe no longer needed American farm products, at least not in anywhere near the quantity that it needed them during the war. But the Americans had greatly expanded their operations and now a glut in the agricultural market appeared, and agricultural prices dropped away to nothing. Thus for example: wheat prices in 1919 were at $2.15 a bushel. The farmers were doing very well! But by the fall of 1920 the price had fallen to $1.44 a bushel. And by 1922 the price was down to 88 cents a bushel! Indeed, in his sales the American farmer hardly recovered the cost of producing his products much less make a profit or income for him and his family. But even worse, he owed huge amounts of money to the local banks that had lent him the money to buy all this additional land and machinery during the war. And he now had no way to pay back those loans or mortgages. One by one, farmers lost their land to the banks. Rural bank failures. But banks were not in the business of farming. Instead of money returning to them as payments for the loans and mortgages, the banks received in default the title to these failed farms. To recover their money, they could sell these farms – but to whom? And when they did it was always for far less than the money that they themselves had originally invested in the mortgages and loans to the farmers. So it was that the farmers' troubles were simply passed on to the banks. Thus in the early 1920s, the rural banks began also to fail one by one. Deep misery set in on rural America. Thus for rural America, the 1930s "Great Depression" had already arrived – ten years early. And rural America would not really come out of this situation during the rest of the decade – at which point the rest of the American economy would join rural America in the misery known as "The Great Depression." |

(Tragically, my grandfather, a bank president, experienced the same catastrophe)

TRADITIONAL AMERICA PRESSED HARD FOR THE CELEBRATION OF AMERICA'S GREAT POLITICAL AND SOCIAL TRADITIONS |

National Archives

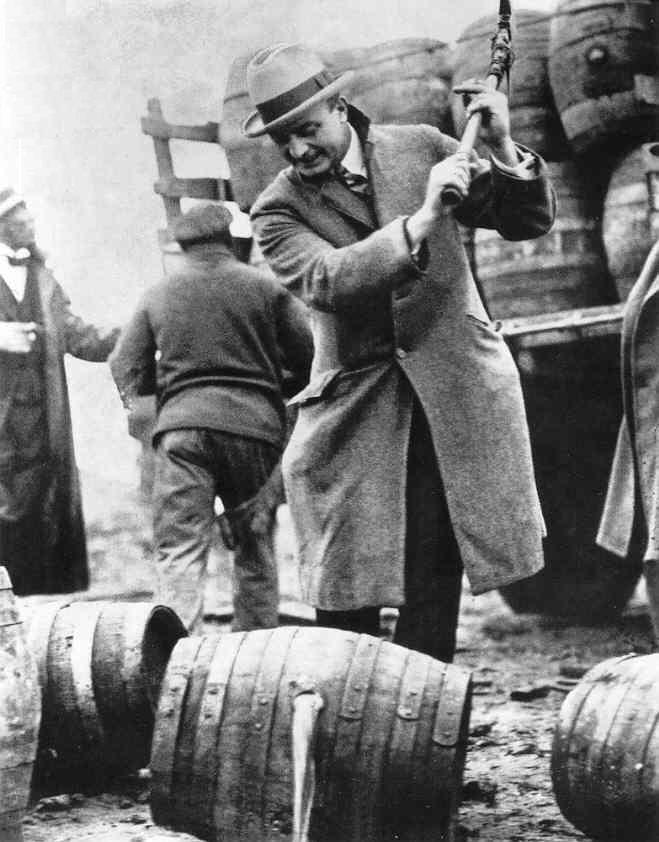

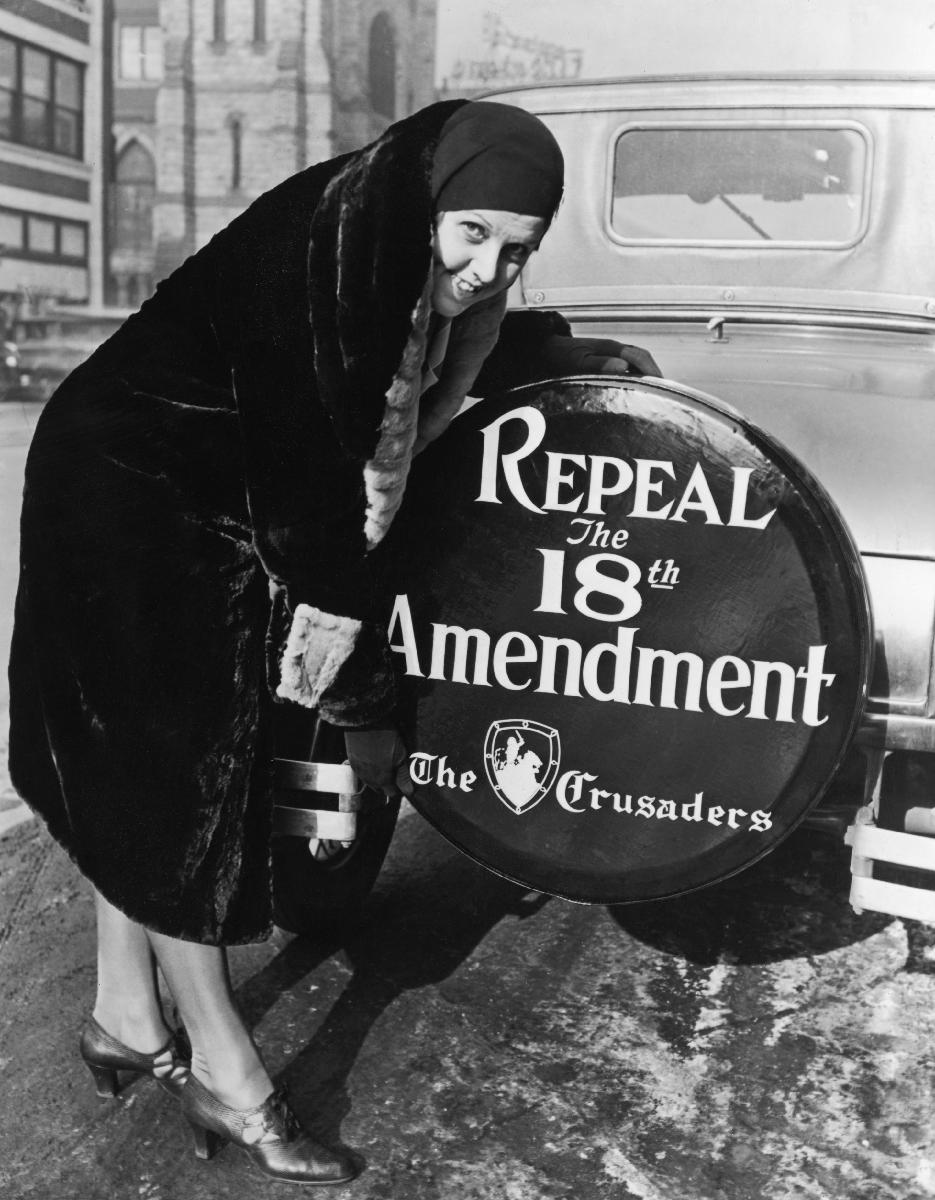

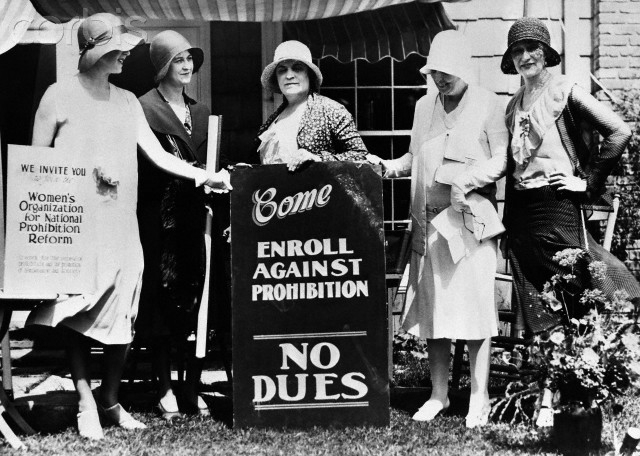

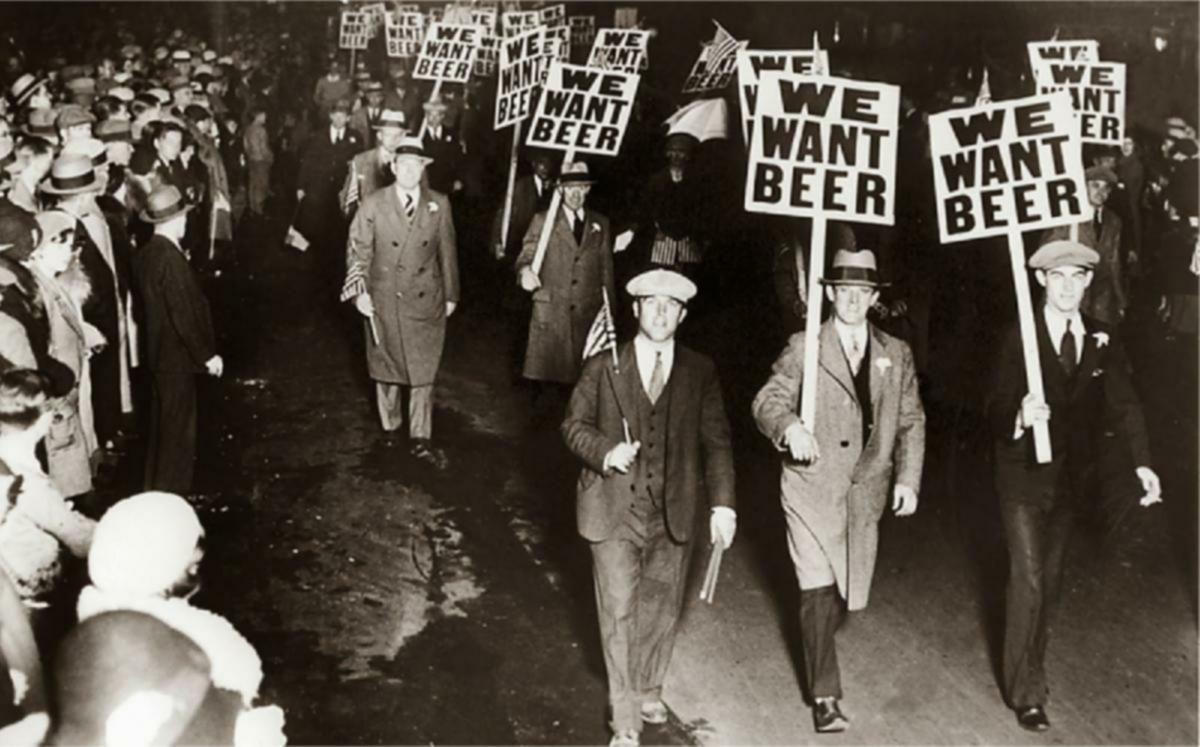

ULTIMATELY PROHIBITION WAS TRADITIONAL AMERICA'S WAY OF REGISTERING ITS STRONG DISAPPROVAL OF THE NEW CULTURE |

|

Prohibition

Then there was this matter of the issue of the prevention or prohibition of the drinking of alcoholic beverages, an issue that divided America deeply. Perhaps most galling to rural America was the proliferation in urban America of the speakeasies (illegal bars), operating in brazen defiance of the new Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution outlawing alcoholic beverages. WASPish rural and small-town America, especially the feminine portion of it, had actually for quite some time taken up arms against one of the great sins of men, the excessive drinking of alcoholic beverages. WASPish Christian morality had always been negative about alcohol, especially its easy ability to lead to drunkenness and alcoholism, which were most definitely great sins. But immigrants coming from Europe – Irish, Germans, Italians, Polish, etc. – seemed not to have this anti-alcohol ethic, alcohol being part of their daily diet. These immigrants for the most part upon

their arrival were consigned to urban or industrial slums, farmland no

longer being free for the taking from the Indians (the frontier had

finally closed with the last Indian lands claimed by White frontiersmen

farmers in the late 1800s). These immigrants were forced to find jobs

in mines and factories where there was a great need for unskilled

labor. But working conditions were terrible, the wages minimal, and

life (to quote Hobbes) nasty, brutish and short. Men looked forward to

payday when they could stop at the corner tavern on their way home from

work and drown their sorrows in the bliss of alcohol. Their wives of

course were upset that with things as troubled as they were, to have

that money go to a drunken spree was heartbreaking. This whole scenario

was one of deep tragedy. Temperance (moderation) easily turned into total prohibition as the best solution to the problem. And so a movement began to actually place this reform of total prohibition of the drinking of alcoholic into the Constitution as one of its amendments. And indeed, in early 1919 Prohibition took effect with the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment. |

Dumping booze

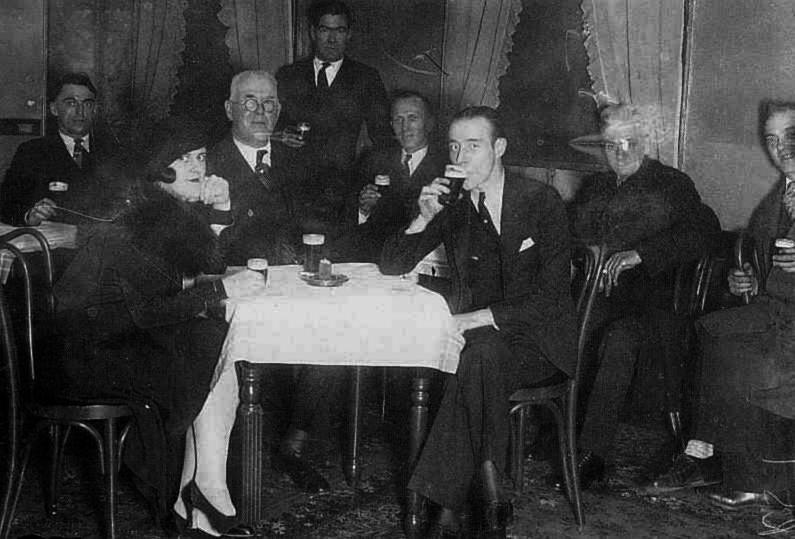

BUT "NEW AMERICA" HAD A WAY OF STRIKING BACK AT TRADITIONAL AMERICA'S

EFFORTS TO BLOCK CHANGE |

|

Urban Resistance to Prohibition

But urban-industrial culture did not

take well to this imposed reform. It was understood (probably

correctly) as simply a slap in the face of urban America by rural

America – and urban America decided to strike back with a loud and very

visible defiance of this law. Indeed, the culture that Prohibition was

aimed at, urban America, seemed to actually increase its alcoholic

consumption behind the closed doors of the speakeasy bars, which

everyone (including the police) knew about quite readily.

The fast, easy money to be earned by the sale of illegal liquor (and

other social services!) naturally led to the growth of a large, wealthy

and very violent social structure: the "mob," constructed heavily along

the lines of the Italian (actually Sicilian) Mafia, although the Irish

and others also had their versions of the mob. Police and judges were

paid to look the other way, and in general urban America turned into an

even greater affront to the moral sensitivities of WASPish America. And

the cities loved the pained outcries of rural America. Prohibition had

become the gauntlet thrown down in the growing urban-rural cultural

divide impacting the nation.

|

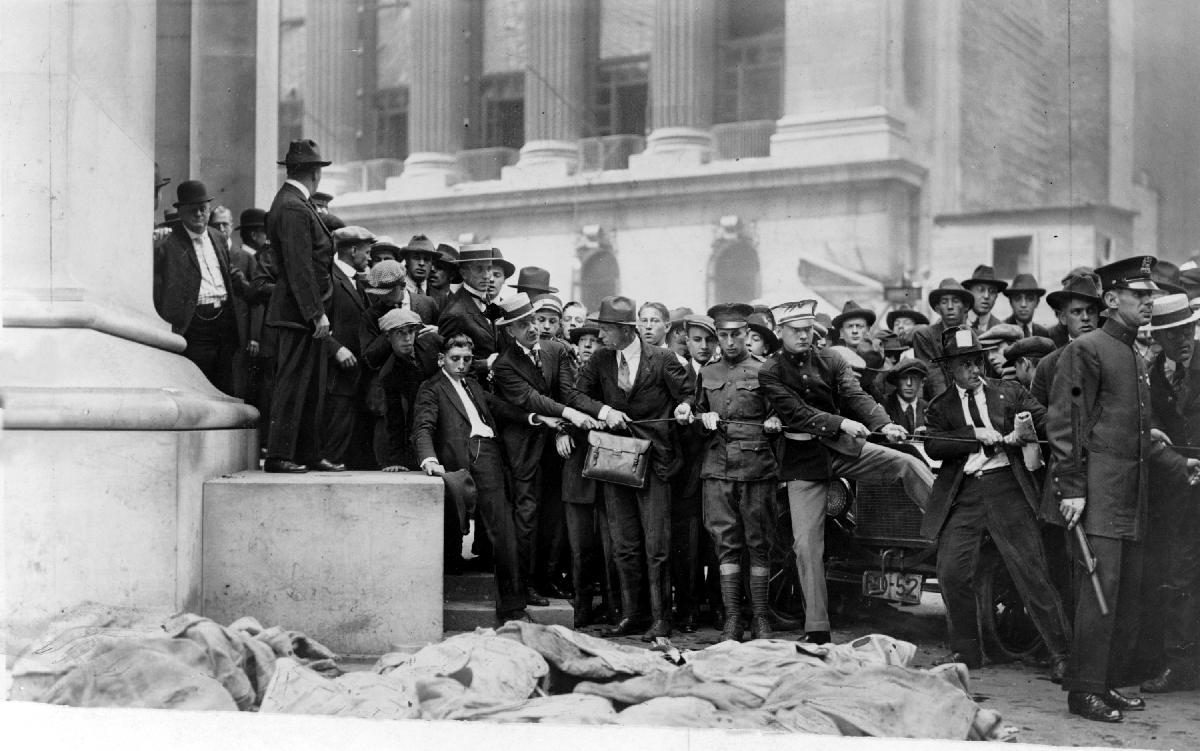

Library of Congress

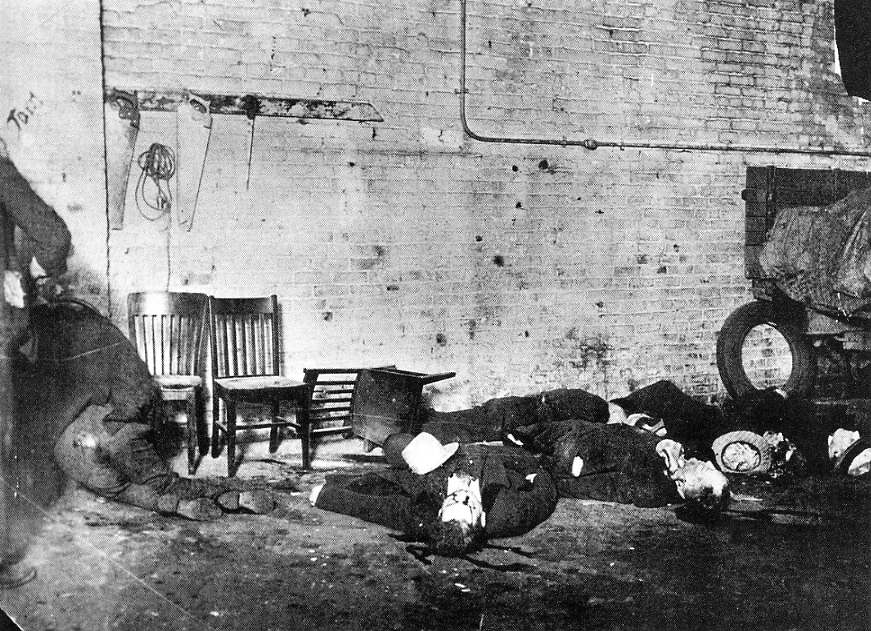

MEANWHILE, AMERICAN CITIES COME UNDER INCREASING CONTROL

BY THE "MOB" |

of gangsters of the rival Bugs Moran gang in Chicago – February 14, 1929

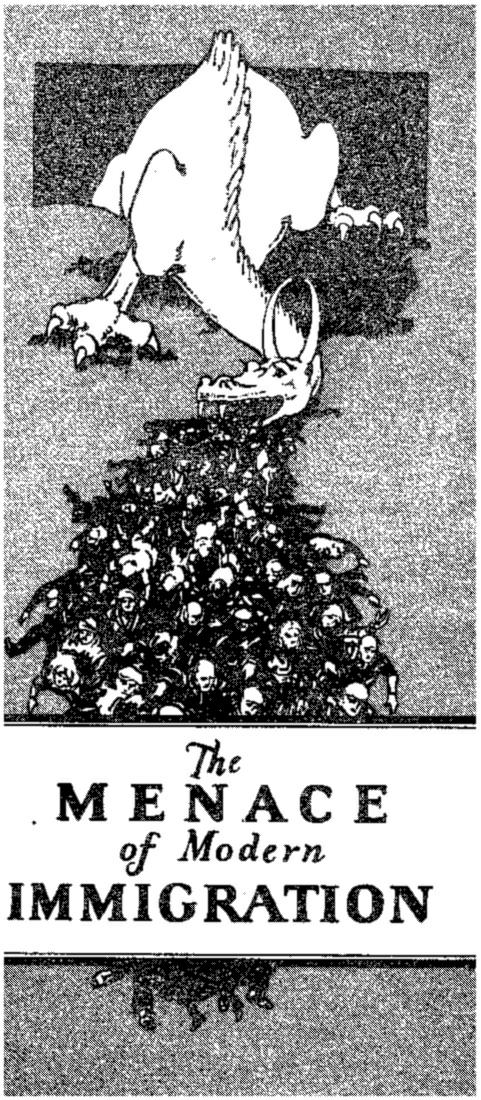

AMERICAN XENOPHOBIA |

|

Understandably, America was a very attractive society ... drawing Europeans of all variety to the land where supposedly "the streets are paved with gold"! And America had always been a society of immigrants. Consequently, there were very good ways to bring immigrants into American society on a well regulated basis.

|

|

Nonetheless, the flood of Europeans to America after the trauma of the Great War was upsetting a lot of Americans ... who saw this simply as an invasion of outsiders. They were not happy! Along similar lines, immigrants in general become a target of traditionalist America after the war, being by this time mostly: 2) religiously – Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox 3) politically – often sympathetic to one or another of the disgruntled European workers movements of Socialism, Communism, or even Anarchism

|

|

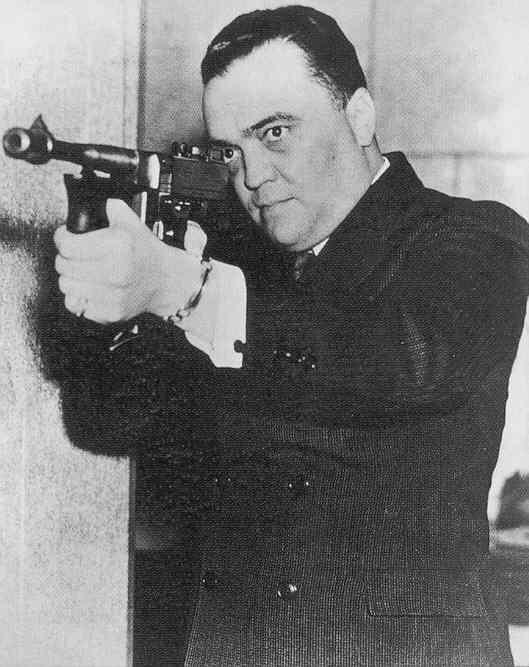

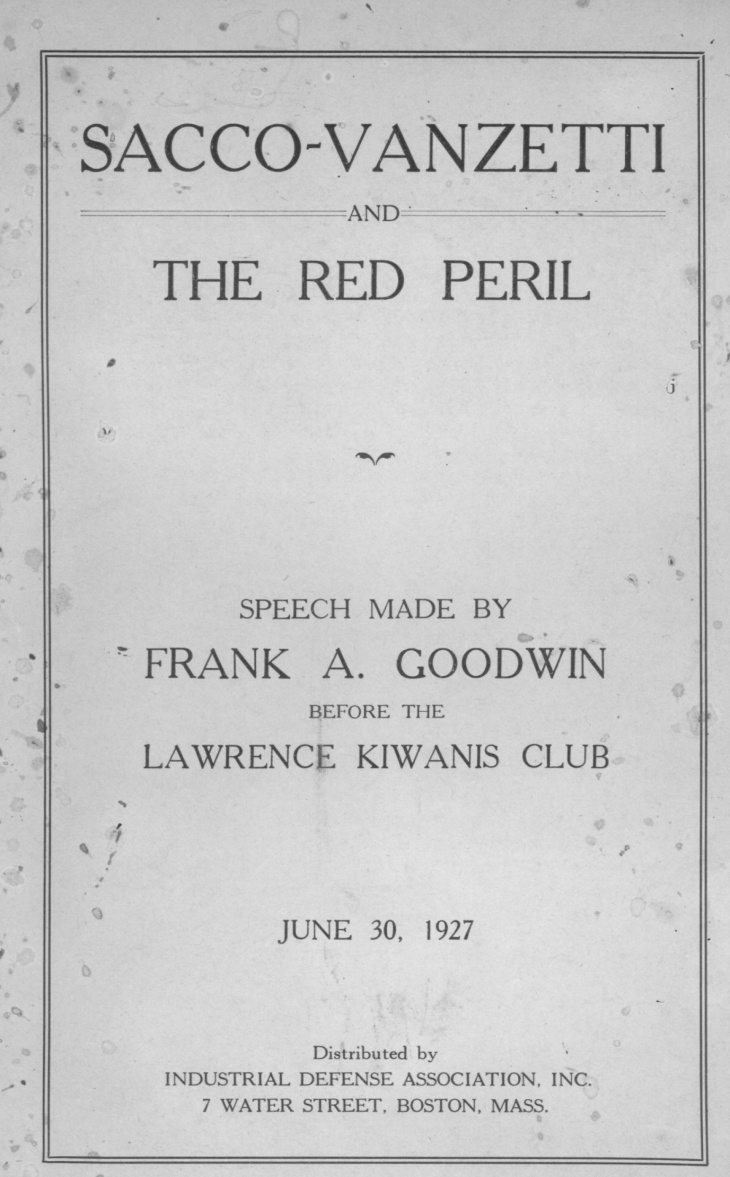

The Great "Red Scare" in America. Relating closely to this mood of xenophobia was the huge Red Scare

Relating closely to this mood of xenophobia was the huge Red Scare that captured the imaginations of Americans (urban as well as rural) after the war, and into the first part of the 1920s. This was not without cause, however. Not only was this fear inspired by the spectacle of European societies caught up in class warfare – inspired by a spreading Communist urge of an angry European working class as well as an equally aggressive spirit of anarchism, the close cousin of Communism – but also by a similar social agitation which seemed to be brewing in America itself, especially among recent immigrants to America’s cities from Southern and Eastern Europe. It was no secret that from Southern Italy

came a large number of followers of the Italian anarchist Luigi

Galleani, who brought with them their radical political instincts. At the forefront of the movement to stop such radical violence was Wilson’s Attorney General, Mitchell Palmer. Although he started out cautiously in his campaign against foreign agitators, he turned savagely against immigrants suspected of radical views after his home was blown up (along with the bomber himself, the Galleanist, Carlo Valdinoci). Palmer hired 24-year-old J. Edgar Hoover to gather evidence and lead raids against such radicals. Files were gathered on 60,000 people and thousands were actually arrested in the period between November 1919 and February 1920. However, Palmer's plans for a presidential bid (his activity was making him a popular public figure) crumbled when a major Red uprising he predicted for May 1, 1920 failed to materialize.1 Then on September 16, 1920 a massive bomb exploded in the busy street in front of the Wall Street offices of the J.P. Morgan bank, killing 30 people and injuring 150 others (8 of whom would also die of their wounds). Although there was no precise evidence identifying the perpetrator of this vile event, suspicions were directed toward an Italian Galleanist anarchist, Mario Buda (verified as indeed the culprit 35 years later by a fellow anarchist and by Buda's nephew) who soon returned to Naples and thus was never apprehended.2 Americans were shocked. 1May Day had long been the chief holiday of the Socialist Labor Movement in Europe. 2This was apparently a Galleanist retaliation (the first of many to follow) for the arrests of Sacco and Vanzetti.

|

|

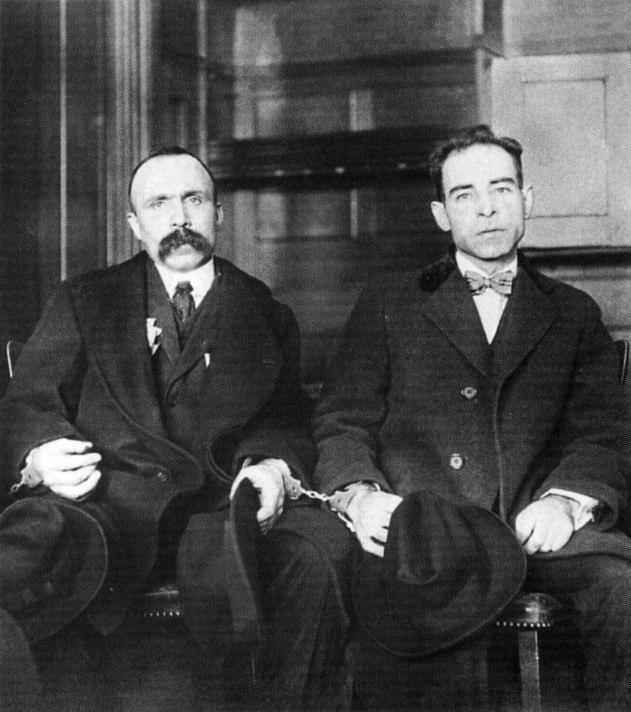

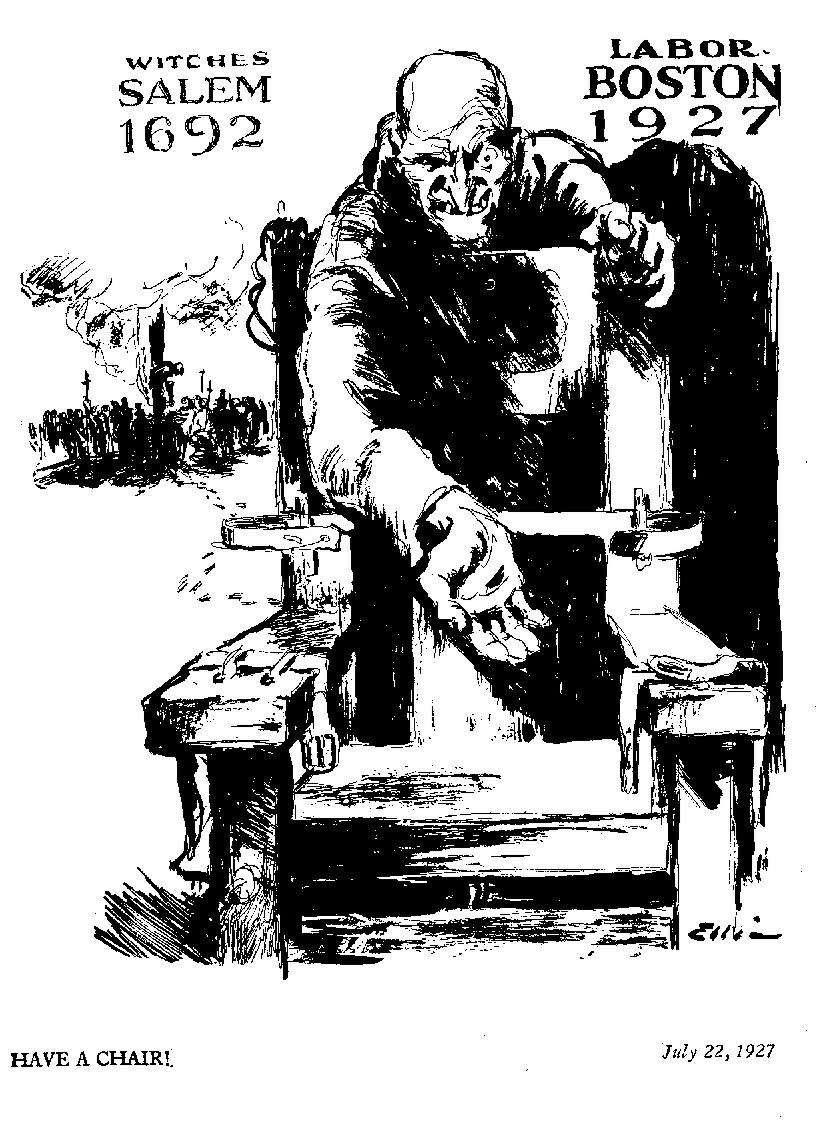

The Sacco and Vanzetti trial

Another event was to rock the nation, not just in 1920 when the event occurred, but over the next seven years as the nation – and even the world – debated the event and the way it was handled by the American justice system. On April 15, 1920 robbers held up and killed one of two men transporting the company payroll of the Slater Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts. Suspicions went immediately to a group of local Galleanist anarchists, of whom Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested and charged with the crime. The only real evidence to work with were the casings of bullets used in the attack. Testimonies by witnesses were confused and claims were made that the police had manipulated the evidence. Also there was a rush to judgment by the presiding judge, which later would become a major point of those who claimed that the two men were unfairly tried and sentenced for the murder the following summer (July 1921). Almost immediately the court case became something of the case of the century. Writers, academics and even artists got into the act, protesting the probable innocence of the two Italians, citing the growing xenophobia (fear/hatred of foreigners) of Americans as the only driving force behind the conviction. For the next six years the case was debated widely as the case was appealed through the American court system. Even the world got in on the act. Americans were widely understood to be cowboys when it came to justice, and the assumption arose that this was all nothing more than a typical vigilante lynching for which Americans were famous. Even the Pope intervened on Sacco and Vanzetti's behalf, asking Americans to check their motives. Then when finally in 1927 the sentence of death was issued for the two accused, protests (even riots) broke out in a number of the world's major cities. Nonetheless in August of 1927 the two were put to death in the electric chair.3 3The case continued however to draw the interest of journalists, artists and political activists over the decades that followed. In 1977 the liberal Massachusetts Governor Michel Dukakis issued a formal proclamation that the case was clearly unjust and that Sacco and Vanzetti's names should be cleared of the crime. However subsequent statements (most recently in 2005) by Italian colleagues of both men made it fairly clear that Sacco had indeed done the shooting and Vanzetti had been involved … though only in the robbery portion of the event.

|

ANOTHER SIGN OF THE TIMES WAS THE RAPID GROWTH OF THE MEMBERSHIP OF THE KU KLUX KLAN |

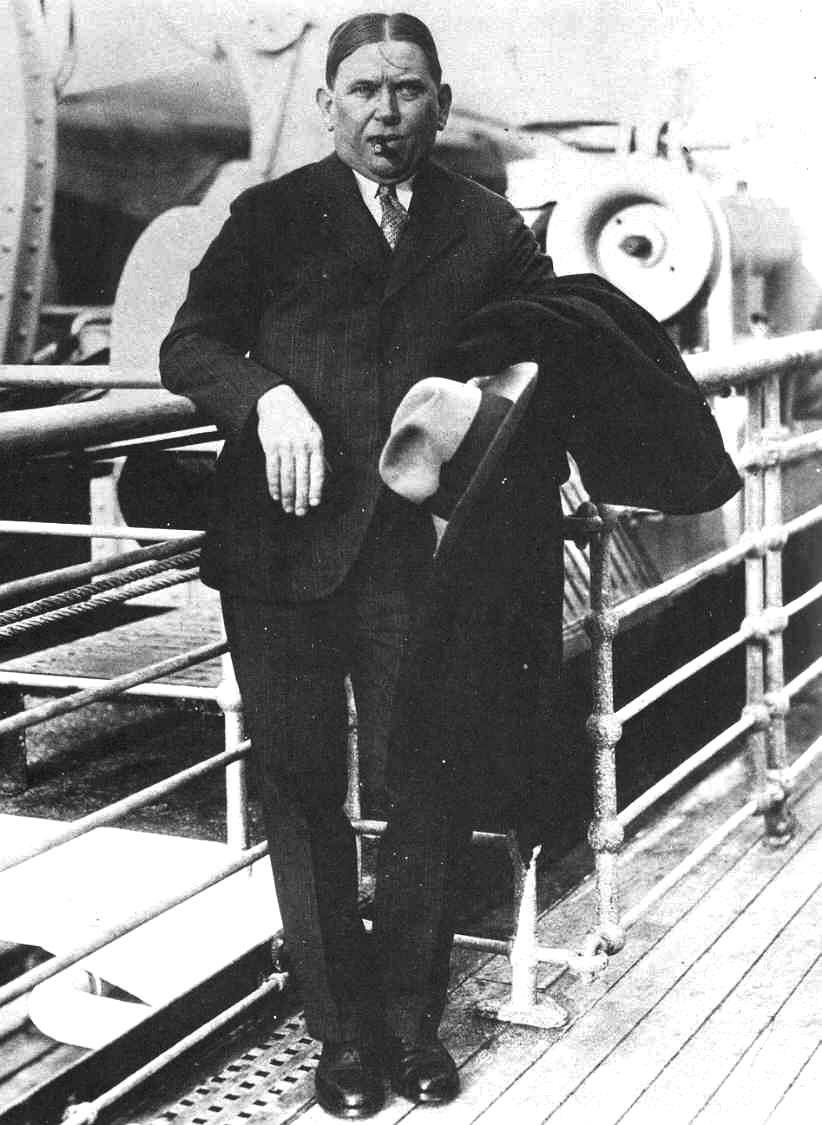

"Back to Africa" movement led by a rather colorful Marcus Garvey

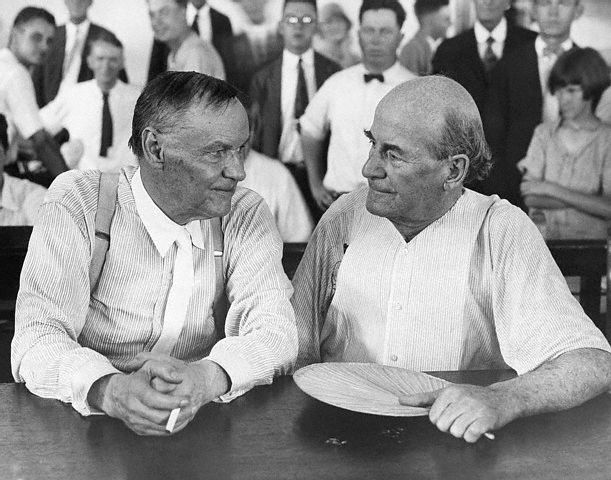

THE "SCOPES MONKEY TRIAL" – DAYTON, TENNESSEE – 1925 |

|

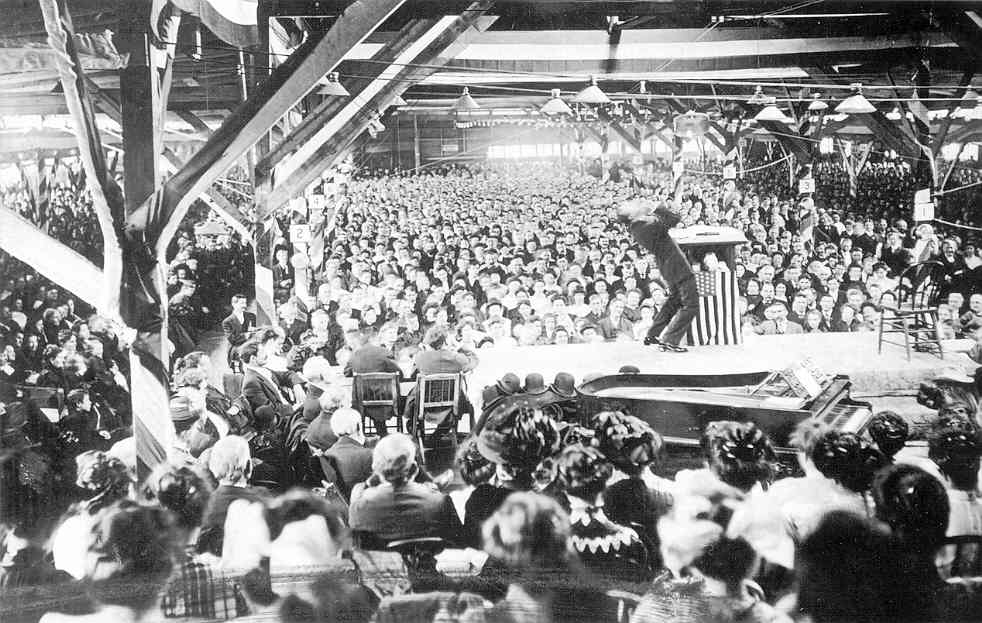

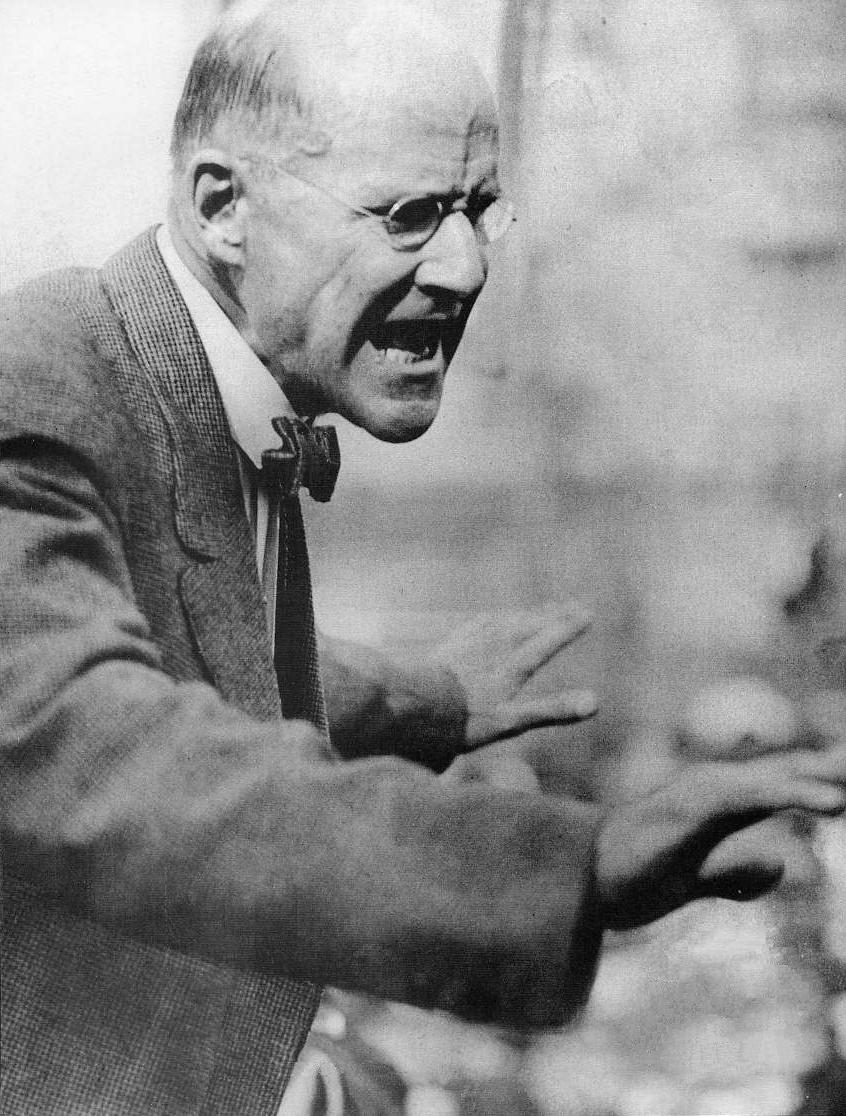

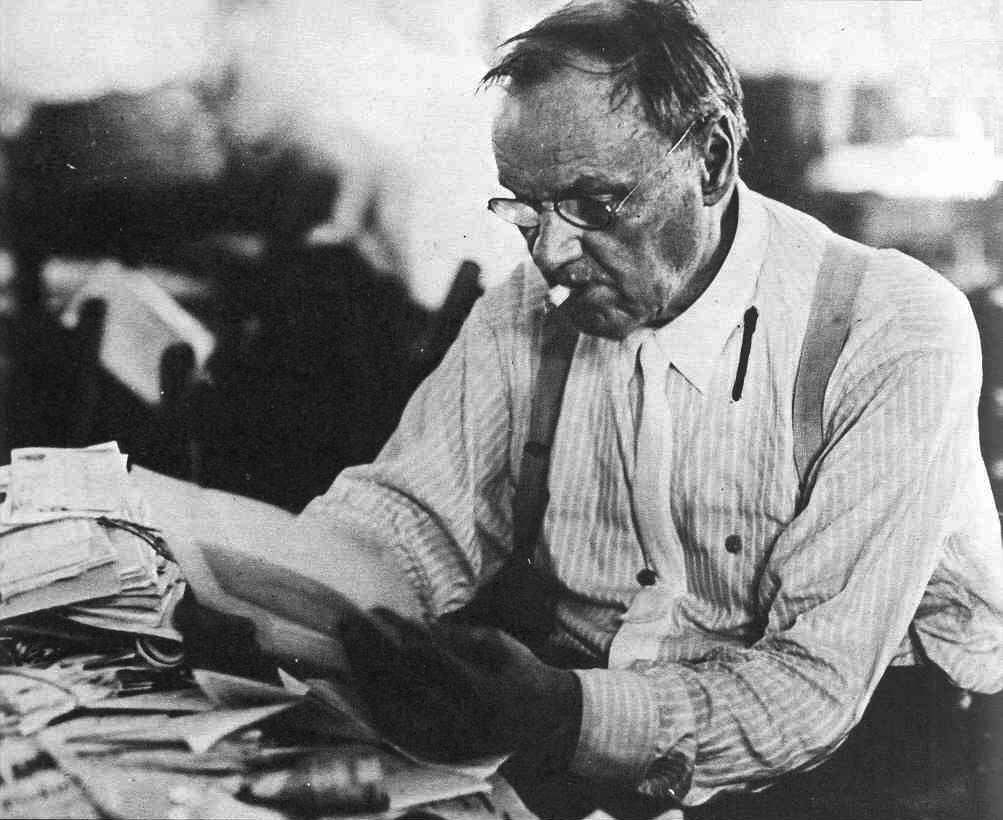

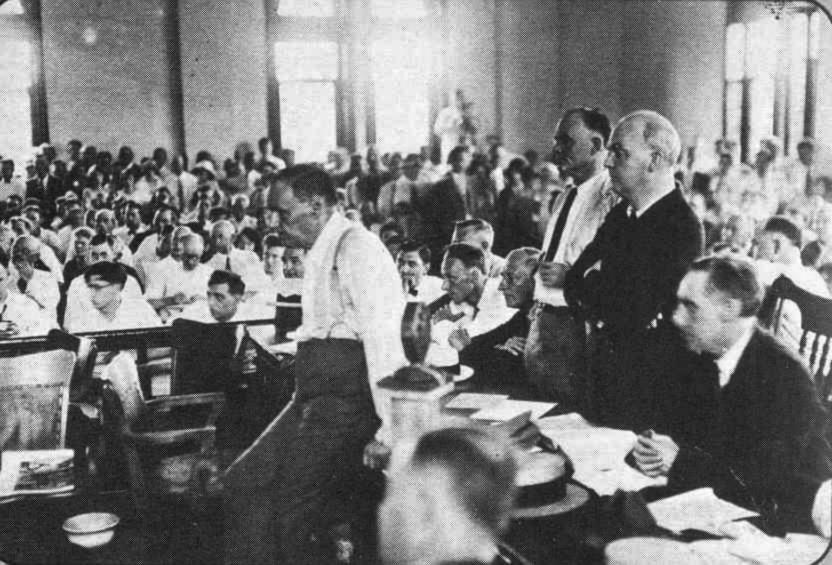

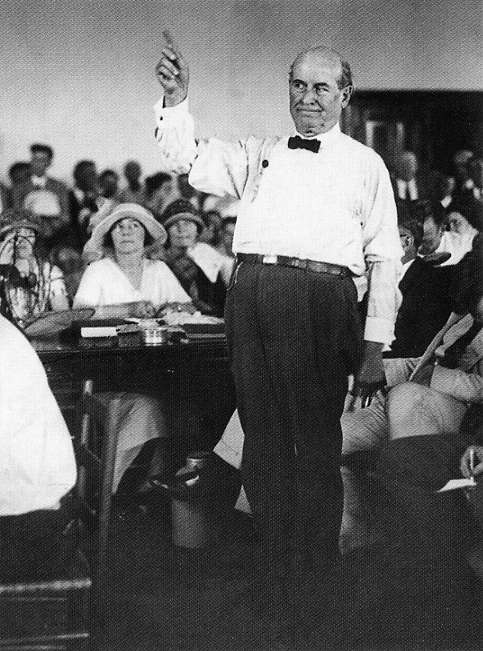

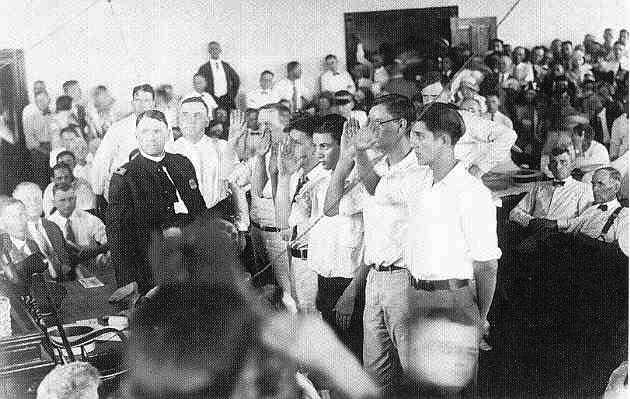

Darwinism as a

Major Cultural "Hot Button" But undoubtedly the most dramatic confrontation of the decade between the two cultures occurred over the issue of the teaching of Darwin's theory of evolution in the public schools. In 1925 the two sides, liberal urban America and conservative rural America met for something of a showdown in Dayton, Tennessee, over the question of teaching Darwinism in Tennessee’s public schools. The battle was over the fundamental question: was man descended, as Darwin stated, through the evolutionary process of natural selection ("survival of the fittest") from some early version of a primate (something of an early "monkey" specie) – or was he, as the Bible states, created fully as a man by God in a single event? The confrontation came to pass when in May of 1925, a group of Dayton civic leaders met at F.E. Robinson's Drugstore and decided to challenge Tennessee's new statute forbidding the teaching of Darwinist evolution. One motivation for holding the trial in Dayton was to revive the town's flagging economy. They knew that this would somehow put Dayton on everyone's map (and indeed it did!). The mastermind behind this event was George Washington Rappleyea, an engineer and geologist who managed the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company. Rappleyea was widely credited with suggesting that Dayton challenge the new anti-evolution statute. Cooperating in this venture was the twenty-four-year-old John Thomas Scopes. He was teaching at the local high school, his first job after graduating from the University of Kentucky in 1924. He taught algebra and physics, served as athletic coach, and occasionally substituted in biology classes at the Rhea County High School. The idea was that he would teach Darwinist biology – at least once – in violation of the state’s law prohibiting the teaching of Darwinism. This act would then set up the opportunity for the legal world in Tennessee to decide whether such a law was indeed constitutional. During the extremely hot summer of 1925 the "Scopes Monkey Trial" riveted the attention of the nation as newspapermen from all around the country crowded into the steaming courthouse to follow the trial. The old political warhorse, William Jennings Bryan, represented WASPish America, with its fervent dislike of Darwinism. Representing the Darwinists was Clarence

Darrow, the celebrity New York lawyer who had dazzled the nation with

his clever defense of two society boys who had killed a young

fourteen-year-old neighbor in order to see what it would be like to

commit the ultimate crime and to prove their Darwinian superiority

(Darrow blamed their actions on the extravagantly wealthy

socio-economic circumstances that had distorted their moral

sensitivities). Darrow also represented the fast-rising urban, secular

culture which ridiculed the superstition of the traditional Christian

culture. Backing up Darrow was the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which was to become the leading voice behind a movement to replace WASPish Christianity with Secular-Humanism as America’s cultural-religious underpinning. Which side actually won the 1925 contest depended on the natural sympathies of the person giving answer to the question. From pulpits, anti-Darwinism seemed vindicated by the fact that the judge decided to support the law prohibiting the teaching of Darwinism in the Tennessee public schools. But the up-East urban newspapers celebrated the quite obvious (obvious to them anyway) intellectual victory of the scientific Darwinists over the superstitious, backwoods fantasies of the anti- Darwinists. Closing arguments were not allowed

(defense attorney Darrow refused and thus prosecuting attorney Bryan

was not permitted to do so either) and the sentence of guilty was

quickly decided in matters of only minutes on July 21. But Bryan

published his proposed closing argument subsequently. It is well worth

the read because it is actually prophetic:

|

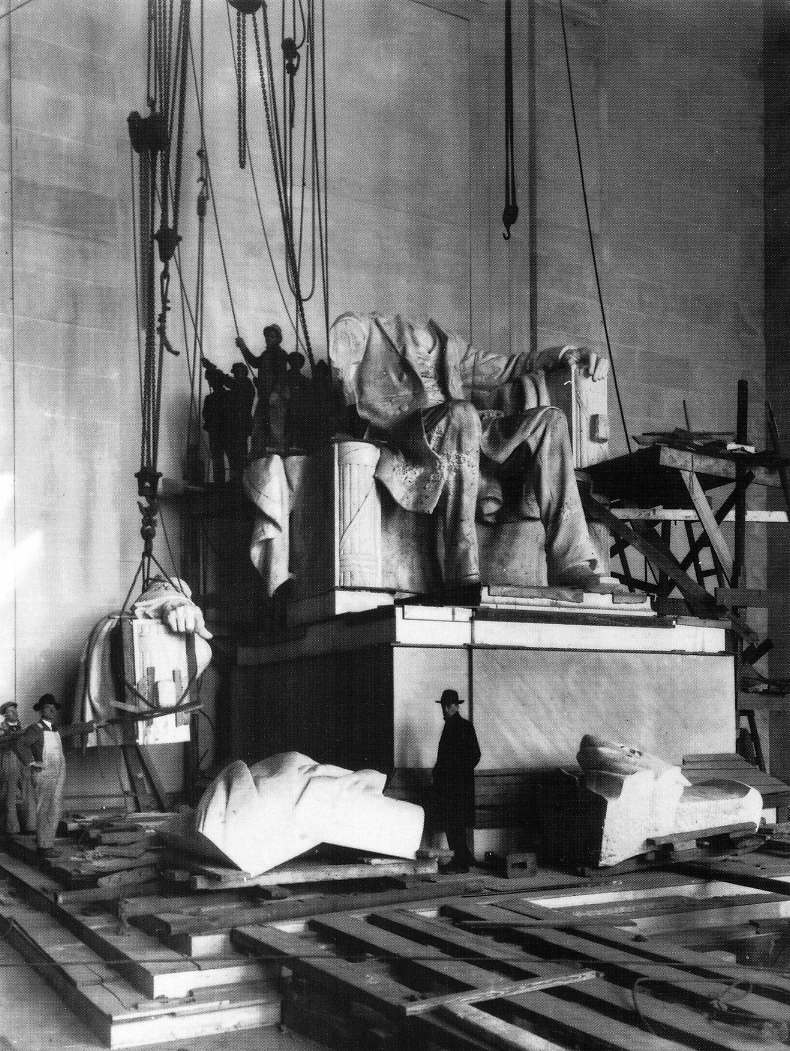

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Institution Archives

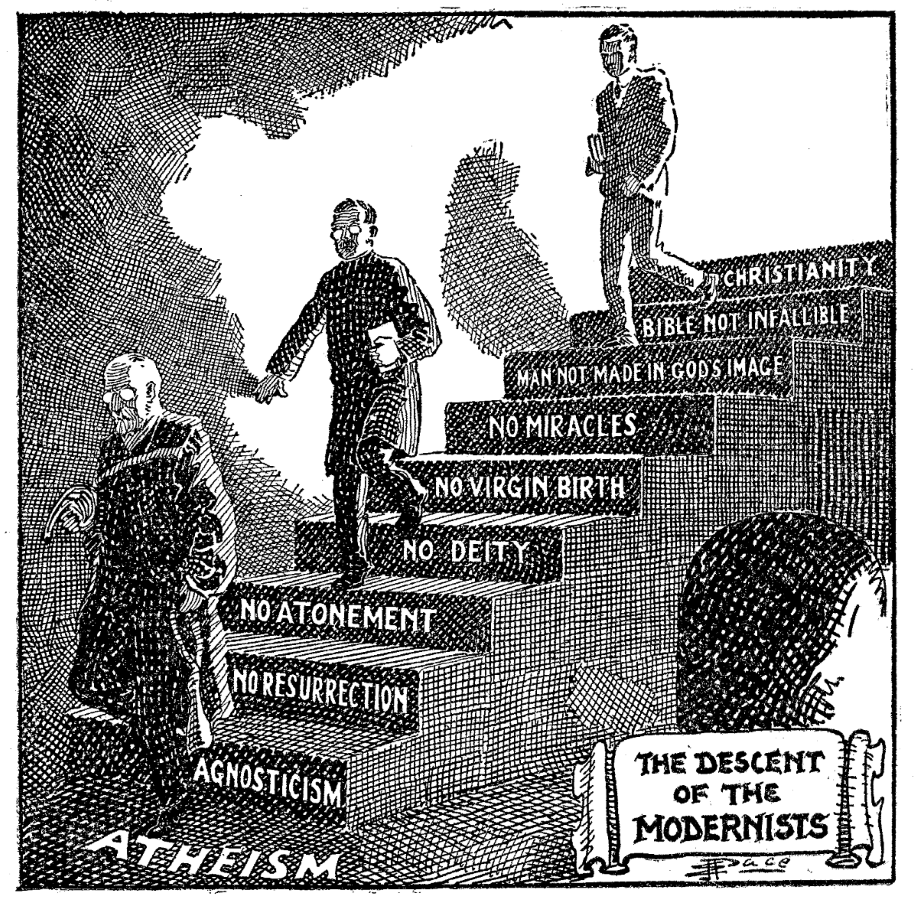

CHRISTIAN FUNDAMENTALISM vs. CHRISTIAN LIBERALISM |

|

This deep urban-rural cultural divide also registered itself as a deepening split within the Christian community itself. There were a number of issues that were behind this split, though one, the matter of biblical inerrancy, was definitely the most important. Almost everything else about the Liberal-Fundamentalist split followed from the ongoing issue of biblical inerrancy. In the early 1900s the question of biblical inerrancy gathered force as a divisive issue, first within the Presbyterian denomination and then soon within the other mainline denominations. Heresy trials abounded as theologians and pastors lined up on one side or the other of the issue. For a time the Presbyterian denomination favored the Conservative view, demanding that all pastors adhere to five basic doctrines in order for their ordination to be in good standing with the denomination. But Liberals or "modernists" were gathering strength within the denomination. And with the unification with the Cumberland Presbyterian denomination, the Presbyterian Church shifted strongly toward the Liberal side of the debate. Meanwhile, Presbyterian layman, Lyman Stewart, sponsored a new series of publications entitled The Fundamentals published between 1910 and 1915. This would become a rallying point for a number of Conservative theologians of a wide number of Christian denominations. In 1915 the Conservative journal, The Presbyterian, finally published a declaration entitled "Back to Fundamentals." And thus the term '"Fundamentalist" was brought into greater use to describe Conservative Christian theology. At the same time the Liberal side of Christianity was taking a broader (Conservatives claimed shallower) approach to the faith, admitting that there was more than one road to God, that God’s love extended to the saved and unsaved alike, and that Christians ought to be more ecumenical among themselves (ignoring doctrinal differences among Christians of all types) and more accommodating in their outreach to other cultures.

On the other hand, one of the foremost of the believers in the Christian Fundam But the Liberal-Conservative balance of power was shifting within the Presbyterian denomination during the 1920s. When in 1928 the Presbyterian General Assembly voted to move Princeton from a traditionally Conservative theology to a more Liberal position, Machen and two other Princeton professors withdrew from the seminary to start a new one in nearby Philadelphia: Westminster Seminary.

|

HOWEVER, EVEN IN URBAN AMERICA A STRONG SENSE OF

CYNICISM AFFLICTS THE "ROAR" OF THE "ROARING TWENTIES" |

|

Actually, all this fascination with the exciting world of massive materialism and unlimited personal freedom seemed at times even to urban America to exist simply to cover over a darker suspicion about life, a suspicion that lurked just below the surface of all this hoopla. The Great War – and its inevitable outcome of nothingness – had shaken the moral foundations of the American nation (as it did with every other participating nation) to the very core of what the society understood as being right and wrong. A form of cultural cynicism set in following the collapse of the Wilsonian dream in America. Many Americans (and Europeans) took the attitude that you had better enjoy life while you had it. "Eat, drink and be merry today because tomorrow you may die." Further, be wary of the high Idealism of those who want to invite you into some kind of higher world. Their world is only a fiction. The only world that really exists – or matters – is the one immediately in front of you. Such an attitude was considered being truly "realistic," and sophisticated. In keeping with this mood of rampant

cynicism, the general understanding was that there were no rights and

wrongs, only just human impulses that people needed to be socially free

to follow out. Whether these impulses were right or wrong (unless they

were obviously self-destructive) was a matter that no one was supposed

to be in a position to be a judge, either of themselves or of others. Thus free-thinking artists and intellectuals boasted of their escape from the intellectual tyrannies of excessive patriotism and superstitious piety. They proudly professed belief in nothing except the immediacy of their own personal existence – and were quick to mock those who held higher ideals, whether founded on the past or the future. Philosophically they referred to themselves sometimes as Humanists, sometimes as Existentialists – but always as scientific. But actually, as pure secularists (believing only in the reality of the immediately surrounding material order), they tended to be simply hedonistic cynics. They supported no causes – nor did they pay much attention to the social requirements of the larger social order. Those expected to lead the post-war societies got little or no support from this self-indulgent social group. The "Lost Generation"

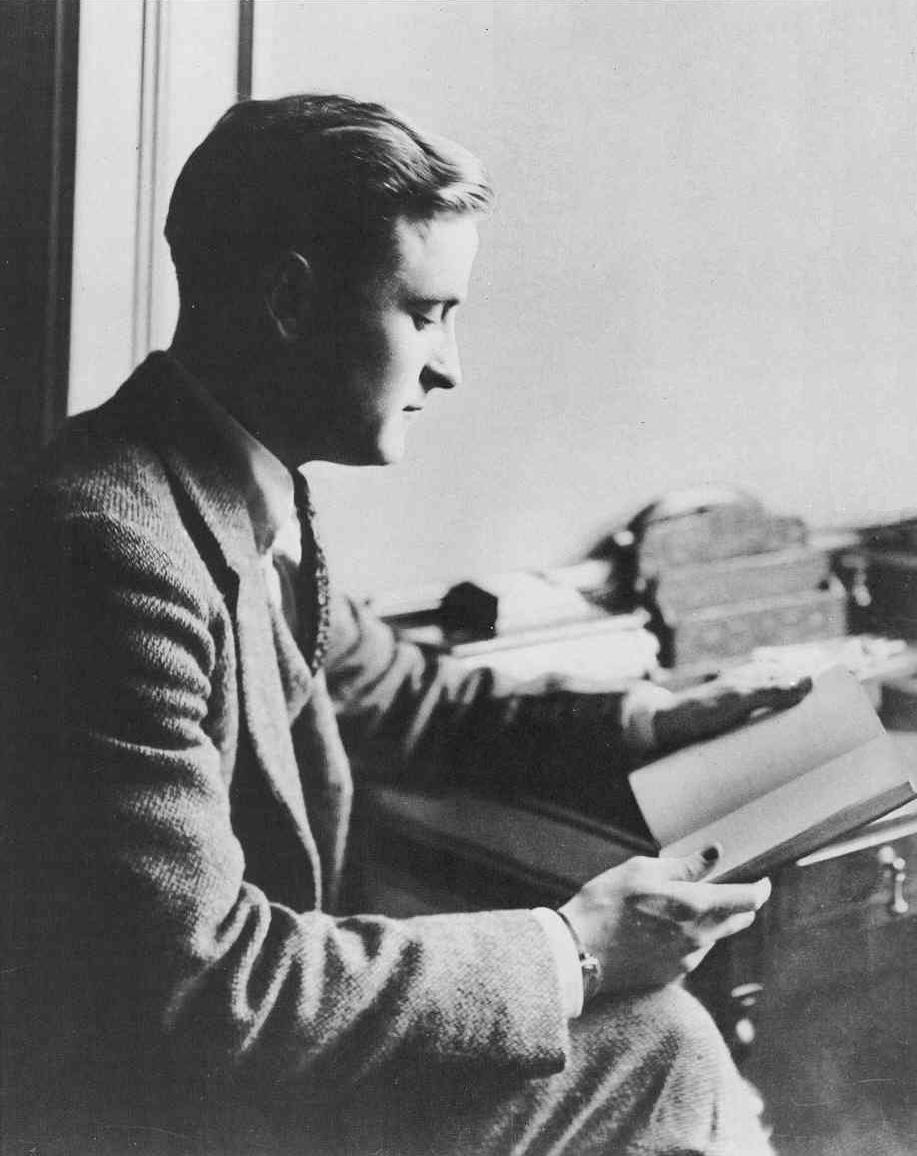

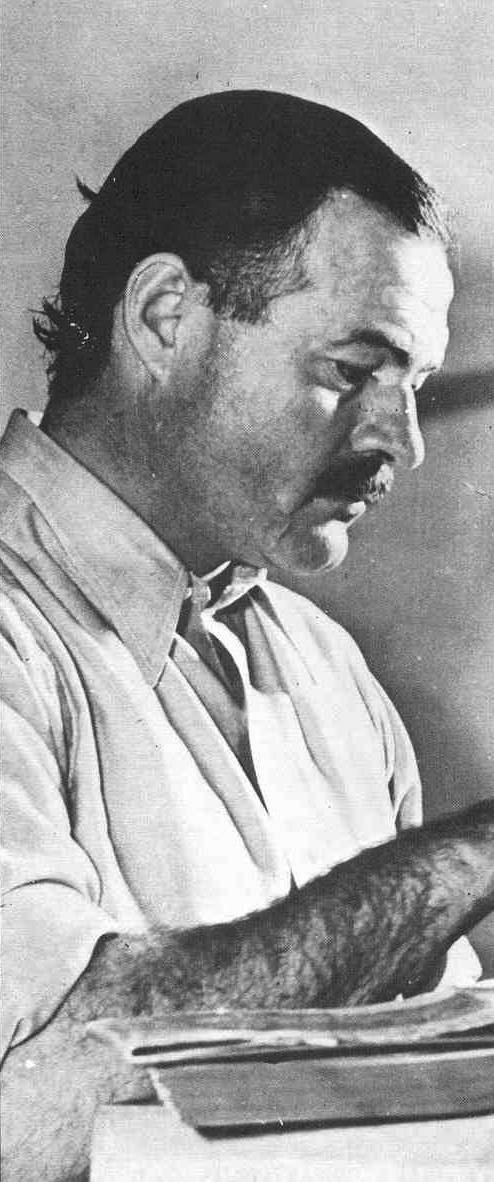

Thus it was that despite all this freedom, despite the material glitz and glamor of the 1920s, there was beneath it all a spiritual emptiness, one that led Gertrude Stein – the grand patroness of the large number of American authors and poets who gathered in Paris to search for meaning to life – to call her literary flock gathered there the "Lost Generation." This group included such Americans as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, E.E. Cummings, and Dorothy Parker. The pointless brutality of the war had stolen from this generation the optimism that had characterized Western culture during the Progressivist Era. True, the material level that the people were able to live at was unparalleled in history. But this now seemed to be very small comfort to these intellectuals, who felt the necessity to plumb the depths of the human soul for some kind of new direction that would be worthy of the kind of commitment to life that they had felt before the war. But mostly they found no such direction or worth. The cynics. The spirit of these lost souls was summed up in such works as Hemmingway's The Sun Also Rises (1926) and Fitzgerald's This Side of Paradise (1920), The Beautiful and Damned (1922) and The Great Gatsby (1925). This last-mentioned novel was highly representative of this Jazz Age mood: behind all the wealth, the fast life, the visible material achievements was a spiritual emptiness and social confusion that results in the murder of the gifted but corrupt young Gatsby and the collapse of the small social group that had once surrounded the Great Gatsby. Likewise, Hemmingway's novels seem to turn on the issue of hopes that lead nowhere because of life's complex, countering circumstances that the human will seems unable to overcome. The "Reds." Meanwhile other intellectuals, repulsed by the failure of American Progressivism to deliver on its promises, turned to other philosophies in the hope that they might find something more substantial to build their social hopes on. Marxism proved to be particularly popular, as the news coming out of Red Communist Russia (tainted by careful manipulation of that news by the Communists themselves) seemed to be working quite well once the Russian Civil War was over and Lenin's Communists had full mastery over the Russian situation, moving the country from feudal backwardness into something quite modern – and quite humane because it was supposedly so very communal. To a group of socially empty intellectual Westerners, this certainly was bound to have a very, very strong appeal. |

"Nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public."

A witty and outspoken Baltimore columnist / author / social-critic of national fame in the 1910s and 1920s. In the 1930s his wit turned bitter and he became an arch-foe of FDR's New Deal

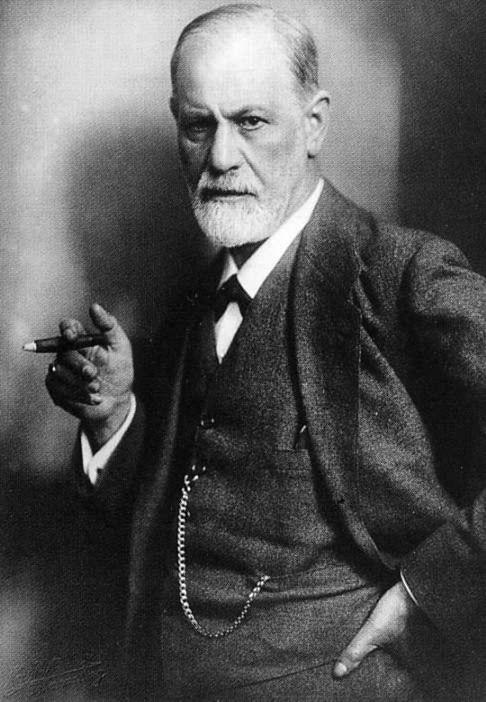

FREUDIAN PSYCHOLOGY CAPTURES THE IMAGINATION OF "HIP" (COOL) URBAN AMERICA |

|

Freudian psychology explains and justifies the American mood

Then there was the degree of comforting logic that

seemingly could be found in the psychological theories of the Austrian

doctor Sigmund Freud. Though none of his theories were derived

through the exacting rigors of the scientific method by which the rest

of science accepted or rejected new truths, Freud's theories went

unquestioned in much of urban America – and in fact were widely

accepted as absolute Truth, because they made sense (when little else

did)! That is to say, Freud's speculations about the motives and

behaviors of humans seemed to offer an explanation to a culture, to a

lifestyle, to a worldview that otherwise seemed shallow and mindless

and beneath the dignity of human reason. Freud revived some element of

hope that what the post-war, post-Christian culture was doing was

actually logical. Basically, Freud explained that we humans did

things that made no sense because we were driven by even deeper,

unexplored urges that ran beneath the level of what our conscious minds

were capable of understanding and thus directing our actions in a

logical manner. Freud speculated that these subconscious urges were

formed in our early childhood out of sexual urges that had to be

repressed in order to form us into reasonably well-functioning social

creatures – that is, responsible members of society. Freud held to the

idea that by going back in our earliest memories and revisiting the

events of our early childhood that were part of this repressive

experience, we might be freed from such repression, and find indeed

fuller, more rewarding lives socially than the ones we were typically

experiencing during the Roaring Twenties! Freud mocked the idea of there being any

ultimate truths that directed human existence, only socially useful

ideas by which we humans were indoctrinated into society. Religion was

chief among these socially useful ideas. Religion in itself could not

be said to be true, for in exploring the many religious beliefs around

the world it became clear to Freud (and most other intellectuals of

those days) that the truths of religion were simply cultural

explanations offered as comfort (such as Santa Claus and the Easter

Bunny) to societies trying to make logical sense of an existence that

otherwise had no particular logic to it. In short, to Freud, religion

was a neurosis, or a useful illusion we fed ourselves in order to

comfort ourselves in the face of a very difficult existence. To Freud,

and to the hundreds of thousands of hip (cool) Freudian followers that

believed Freud to be the supreme prophet of modern times, religion in

itself was completely unrelated to Truth, and indeed was the source of

some of the most illogical and cruel of human acts in history.4 However the followers of Freud failed to

observe the fact that Freudian psychology itself was valued so highly

by them only because "it made sense," ... which thus put Freudianism in

the same category as the religions Freud mocked because they could be

said to be true only because they too made sense to their religious

followers. Freud himself made it clear that just because something made

sense did not make it true. It merely made it socially useful. And thus it was that Freudian followers

followed Freud religiously! Indeed, in all this, Freud and his Freudian

followers were helping to construct a new cultural Truth, contributing

greatly to a new post-Christian religion within Western society, the

Secular Humanism that was sweeping the intellectual circles of Europe

and America.

4Certainly

to the followers of Freud, the experience of the recent "Great War"

exposed such dangerous religious folly, in that each of the contending

parties in the war claimed "Gott mit uns" (God is with us). Surely God

was with no one during the war, unless God was indeed some kind of

cruel monster delighting in watching "God-fearing" soldiers slaughter

other "God-fearing" soldiers in vast numbers.

|

entals and thus a major opponent of Christian Liberalism was

entals and thus a major opponent of Christian Liberalism was