|

The War in Poland The War in Poland The Russo-Finnish War (1939-1940) The Russo-Finnish War (1939-1940) The "Sitzkrieg" in the West The "Sitzkrieg" in the West The Battle of the Atlantic begins The Battle of the Atlantic begins The end of the Sitzkrieg of Phony War The end of the Sitzkrieg of Phony War The Fall of the Netherlands, Belgium and France (May-June 1940) The Fall of the Netherlands, Belgium and France (May-June 1940) The Battle of Britain begins The Battle of Britain begins  The Tripartite or "Axis" Pact The Tripartite or "Axis" Pact American neutrality American neutrality  The fight for the control of the Mediterranean The fight for the control of the Mediterranean The battle for the Atlantic develops The battle for the Atlantic develops The Atlantic Charter (August 1941) The Atlantic Charter (August 1941) The textual material on the page below parallels my work found in

A Moral History of Western Society, © 2024, Volume Two, pages 161-168

... although the page below generally goes into much greater detail. |

|

|

The Germans invade Poland

On September 1st Hitler’s troops invaded Poland without any formal warning - and began to blast Poland into bloody submission. England and France declared war against Germany on September 3rd for this action against Poland. But within two weeks Polish resistance to the German invaders was limited to several small pockets. The "stab in the back" of the Poles by the Soviet Red Army

There was a little over a two-week delay (until September 17) in the movement of the Soviet Red Army into Poland. The Poles did not know about the secret provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty by which Hitler and Stalin had decided to divide up Poland between them. When the Russians did finally cross into Poland, the Poles thought the Russians were coming to aid them against the Germans. Too late the Poles realized that the Russians were invaders as well. The Germans and Russians finally closed forces against the Poles at Brest-Litovsk. By the 28th of September the last Polish pocket of resistance was crushed. On the 29th Poland was formally partitioned between Germany and Russia. Soviet Russia was just as guilty for its part in starting the war. And its treatment of the Poles would be no less cruel. But the English and French would not declare war on Russia as they had on Germany for this invasion of Poland. The Katyn Forest massacre

One of the saddest features of this Russian invasion was the disappearance of about 22,000 Polish officers, civil officials, intellectuals, etc. seized during the Russian occupation of Eastern Poland (1939-1941). In 1943 the Germans, in invading the Russian sector of Poland, announced that they had discovered mass graves at the Katyn Forest: stacks of Poles piled high had been massacred by the Russians. The Polish Government-in-Exile in London asked the international Red Cross to investigate the graves ... leading Stalin to break relations with the exiled Polish government (Stalin set up his own Polish Government - which he later installed in Poland as his Red Army swept through Poland in 1945 in pursuit of the Germans). At the post-war crimes trials the Soviets even attempted to pin the blame for the massacres on Germans who had "confessed" their hand in the massacre. But the matter was dropped when the Americans and English proved not to be convinced by the Russian accusations. It was in fact not until 1990 that the Russians finally confessed that the massacre in the Katyn Forest (and other similar sites) had been specifically ordered by Stalin and Molotov |

The German invasion of Poland

The German invasion of Poland

Nazi tanks roll into Poland - September 1939.

Germans invade Poland – September

1939

German troops attacking

Poland

A Polish girl grieving over

her sister killed by German arial strafing – 1939

Polish infantry, during the

Polish September Campaign

Survivor of German aerial bombardment of Warsaw

| Made in 1939, by US photojournalist Julien Bryan, who was present in Poland during the German invasion. He captions the image: " 'A Boy's weariness.' Ryszard Pajewski was a study in dejection when I saw him sitting on a pile of rubble (below). Only nine, he had suddenly been made the family breadwinner - and there was no bread to be had. Now a truck driver, he remembers that when he saw me last, I was carrying two 'boxes' – my cameras." |

German troops parade through Warsaw,

Poland. PK Hugo J.ger, September 1939

National Archives

200-SFF-52

Jewish men being cowed and beaten by S.S. for the shooting of a police officer in Olkusz, Poland

The "stab

in the back" of

the Poles by the Soviet Red Army

German and Soviet officers

greet each other after having overrun

Poland

Tass

Common parade of Wehrmacht

and Red Army in Brest at the end of the Invasion

of Poland – 23 September

1939. At the center are Major

General

Heinz Guderian and

Brigadier Semyon Krivoshein.

Deutsches

Bundesarchiv

Polish troops taken captive

by the Russian Red Army

One of the mass graves of

Polish officers massacred at Katyn Forest (and elsewhere)

Several of the many layers

of Polish bodies in Katyn Forest mass graves

The Polish Government-in-Exile in London

Polish pilots serving in the British Royal Air Force

|

| Stalin,

now nervous about German advances into Poland (despite their treaty

which set up the whole scenario) in October pressed his neighbors,

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to sign three "Mutual Assistance Pacts" -

which then legitimatized the Russian Red Army’s entry into those

countries and their absorption into the Soviet Empire. He then turned on another neighbor, the Finns, forcing them to give grants of land to the Russians in order to put more land buffer around Leningrad (St. Petersburg). When the Finns refused, Stalin in December 1939 ordered Helsinki bombed and the Soviet Army to move into Finland. But the Finns put up a stiff resistance and the winter proved cruel to the Russian invaders - many of whom simply froze in the snow. Stalin ordered a second, larger invasion in February 1940. France and England hesitantly came forward with offers of aid to the Finns – but even that was too long delayed. Meanwhile, though the Russians had lost a quarter of a million troops to Finland's 25,000 – the losses were comparatively heavier on the Finnish population and by mid-March the Finns were defeated. The result of this war was the ceding of large strips of Finnish borderland to Russia and the falling of the remainder of Finland under Soviet domination. |

Finnish ski patrol on the move against Russian invaders - December 1939

Finnish civilians in the woods to escape another Soviet air raid - early 1940

|

| Having

declared war against Germany, the English and French then proceed to do

nothing ... thus missing a valuable opportunity to catch Hitler off

guard in the West while he was fully engaged in the East in

Poland. Once again it looked as if the Western democracies just

simply had lost all nerve against Hitler. During the rest of the fall, then into the winter and then the spring of 1940 the "Western Front" was quiet. Some in Germany already began to ridicule the "war" with England and France by playing on Hitler's doctrine of Blitzkrieg - "lightning war." The critics called this war in the West a Sitzkrieg - a "sitting war." Some of the English had their own term of contempt for the British and French inaction, terming it the "Phony War." |

|

| The

only serious military action between England and Germany in this early

phase of the war was on the high seas. The naval war began in the

British naval harbor at Scapa Flow when a German U-boat slipped inside

and sank the battleship Royal Oak (October 17th). But with respect to naval action the Germans were up against the newly appointed First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill, who was quite ready to take up the war aggressively at sea … and met with some success. When a German U-boat was able to sink the British battleship Royal Oak at the naval harbor of Scapa Flow (October 14th), Churchill retaliated. A huge naval victory came to the British when three English cruisers chased the German pocket battleship Graf Spee into the neutral port of Montevideo. The German captain, running low on fuel and ammunition and supposing (incorrectly) that the English were assembling a mighty naval armada around the exit of the River Plate, decided to scuttle the ship rather than surrender it to the English (December 13th). This loss of the German battleship proved the only bright moment for the English during the Sitzkrieg (winter of 1939-1940) ... and a boost to the reputation of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill. |

HMS Royal Oak – sunk at Scapa Flow ... with the loss of 800 lives

The scuttled German battleship Admiral Graf Spee – December 13, 1939

... scuttled in the harbor of Montevideo, Uruguay, because the captain believed the ship to be under

attack by a large British naval force (actually not the case at all) ... and did not want the ship to fall

into British hands.

|

|

The Battle of Norway and Denmark (April 1940)

Germany was nearly totally dependent for imports of iron ore for her Ruhr-based steel industry. Some of it came from Alsace-Lorraine, a region restored to France as a result of the Versailles treaty. Now with war begun, that source was totally cut off. But almost three quarters of their ore had come anyway from the rich iron ore fields of northern Sweden. Sweden was a "neutral" in the mounting conflict. But the most direct route for the ore from Sweden to Germany, via the Baltic, was frozen over during the winter. Only the route across northern Norway through the port of Narvik was ice-free year-round. Besides, this was the route that ore reached England from Sweden, providing England with 10% of its iron ore needs. Thus the port of Narvik was strategic for both Germany and England. Without this ore, Germany would be helpless. And England not only needed some of that ore itself, but cutting off the route to Germany would be a big gain for England in its newly declared war against Germany. On the other hand, holding a position in Norway would give Germany naval and air position from which to attack Britain. Hitler had carefully prepared his move on Norway ... cultivating a "Fifth Column" of pro-Nazi Norwegians – led by the Norwegian collaborator Major Quisling – who would aid the German takeover of the country by seizing airfields and ports for the Nazis. The Germans then would be parachuted into the country or would invade various Norwegian ports by amphibious assault from a flotilla of ships. Thus in early April of 1940 Hitler struck out against Denmark and Norway - and the war in the West was no longer a sitting war. The Norwegians fought fiercely, but were soon overwhelmed by the well-planned German invasion. The Norwegian king and cabinet made their escape to England as the country fell to the Germans. Many Norwegians took to the mountains to keep up something of a guerrilla action against the Germans – which never let up during the full run of the war. Meanwhile totally unprepared Denmark fell quickly (in only one day of action) to the Germans. Unlike the Norwegians, the Danes offered no further resistance to the German occupation. |

Hitler needed access to Swedish iron ore, available in winter only across northern Norway.

7-9 April 1940

Campaign Summaries

of World War 2: Norway, including the Norwegian Campaign 1940

www.naval-history.net

10 + 13 April 1940

Campaign Summaries

of World War 2: Norway, including the Norwegian Campaign 1940

www.naval-history.net

German infantry attacking

through a burning Norwegian village.

Deutsches Bundesarchiv

A squad of Danish troops

on the morning of the German invasion, 9 April 1940,

photographed near Bredevad

in Southern Jutland. Two of these men were killed later that day

Deutsches Bundesarchiv

Vidkun Quisling ... Norwegian puppet governing Norway for the Nazis

|

|

The Battle of the Netherlands and Belgium (May 1940)

Just as Churchill was taking command in Great Britain, Hitler turned on his neighbors directly to the west of Germany. On May 9th German troops struck into Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, sweeping westward well to the north of the famous French Maginot Line. German parachute troops were dropped ahead of motorized German infantry, seizing airfields, strategic crossroads and bridges ... as the Dutch countered by flooding their fields and trying to blow up bridges. But the Germans moved so quickly that mostly such efforts by the Dutch of self-defense availed little. Three days later the Dutch Queen and cabinet ministers escaped to England and the next day Rotterdam was completely laid waste by the Germans as a demonstration to the Dutch of what resistance to the German occupiers would gain them. Thus the Dutch surrendered. The Belgians experienced the same Blitzkrieg strategy of the Germans ... though they held out for over two weeks against the Germans. Then on May 28th Belgian King Leopold surrendered himself to the Germans ... and the Belgian resistance collapsed. Churchill takes command in Britain (May 1940)

The British were stunned by these huge German successes. In England Chamberlain sensed growing opposition to his leadership and was rejected by Parliament in his effort to create a broad national-front cabinet. At this point Parliament wanted Churchill to lead the nation ... and the King did indeed ask him to take over on the 10th of May. Three days later, in a speech before Parliament, the new Prime Minister told the country that he could offer no quick road to victory but only "blood, toil, tears and sweat." But his aim was complete victory ... "for without victory there is no survival." The British were ready to stand strong with Churchill now leading them. The fall of France (June 1940)

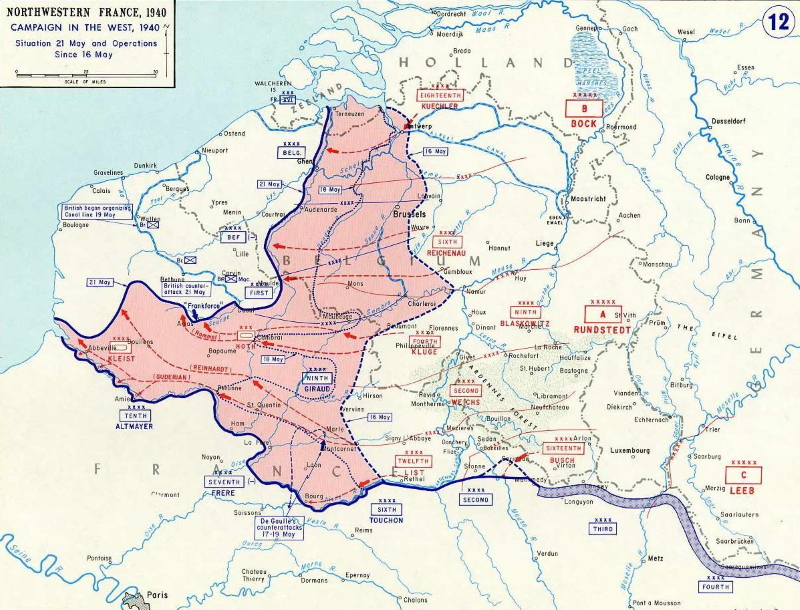

Meanwhile the French were struggling to fend off the Germans. The French had already replaced as prime minister the German appeaser Daladier with the staunch anti-German Paul Reynaud in March ... who had tried to move quickly to ready France for the coming encounter with Germany. But much valuable time had run out for the French, time needed to prepare for the inevitable. Reynaud had tried to help the Norwegians, though Chamberlain’s withdrawal of British forces from Norway on April 28th forced the French then to have to pull back. Poor strategic thinking. Expecting the Germans to attack France across the hills of central Belgium (similar to the Schlieffen strategy the Germans had adopted in 1914 at the beginning of the Great War), French commander Gamelin had wanted as early as March to move French forces north across Belgium to the Netherlands to be in a position to swing behind the Germans were they to attack through Belgium. But at the time both Belgium and the Netherlands had declared their neutrality and Gamelin had the option only to mass huge numbers of French troops in the northwest along the Belgian border in anticipation of an eventual German attack. Here French troops were joined by British troops much in the manner of the Great War (which was beginning to be understood as World War One now that World War Two was clearly taking shape). But several mistakes were involved in French and British thinking. They still did not understand Blitzkrieg and planned to move with concentrations of conventional troops against the Germans (who however were less numerous than the French and British Allies because the Germans had lost a large number of troops in Poland). Their plans rested on the notion that it would take several weeks for the Germans to get across Belgium (in fact it took only a few days) giving the Allies time to secure their positions in Belgium and the Netherlands. But the Germans had no such plans for a massed assault against the French but rather a lighting quick strike slicing through the dense Ardennes forest. Information reaching the French indeed gave indication that such a strategy might be in the making. But sadly, Gamelin was certain that the Ardennes would be too difficult for the Germans to navigate, and expected the Germans to move further north through Belgium where the Allies would be waiting for them. The German attack through the Ardennes Forest. On May 10th the attack through the Ardennes got underway. Parachuted troops were dropped to secure vital bridges across the rivers that threaded through the Ardennes mountains and German tanks and motor vehicles had relatively little difficulty moving swiftly down the lightly defended roads that led through the Ardennes. They then reached northern France and cut right through the middle of the French lines, separating the troops gathered behind the Maginot Line in the French East from the French and British troops gathered in Northern France and Western Belgium. The Allies fought stiffly and hit the Germans hard. But strategically speaking they had been put in an untenable position. The first of the German troops reached the Meuse River (May 12th) and Paris was now very vulnerable. But then the German offensive turned west ... with the clear intention of pushing the Allies backward to the sea and, in order to protect the German right flank in its attack on Paris, eliminating the entire combined British, French and Belgian forces still fighting in that area. The Germans also had huge numbers of French troops trapped in the East of France behind the Maginot Line ... a well-developed French line of defense – which however was aimed toward Germany and not to the rear facing the French interior, making it at this point somewhat useless. By the 16th of May, with Germans rolling rapidly toward the English Channel, Churchill flew to Paris to try to restore French morale, only to find that Gen. Gamelin seemed to have lost all hope for his French troops. The French had nothing left to throw against the Germans. On May 19th Reynaud replaced Gamelin with Weygand in the hope of reinvigorating the French effort. But Weygand did not understand the need for urgency, and moved slowly in organizing a counteroffensive against the overstretched German lines. Ultimately it was again too little, too late. The only serious counter-offensive action undertaken against the Germans was led by General Charles de Gaulle, increasingly operating on his own. Brave though it was, it was hardly adequate considering the gravity of the situation. |

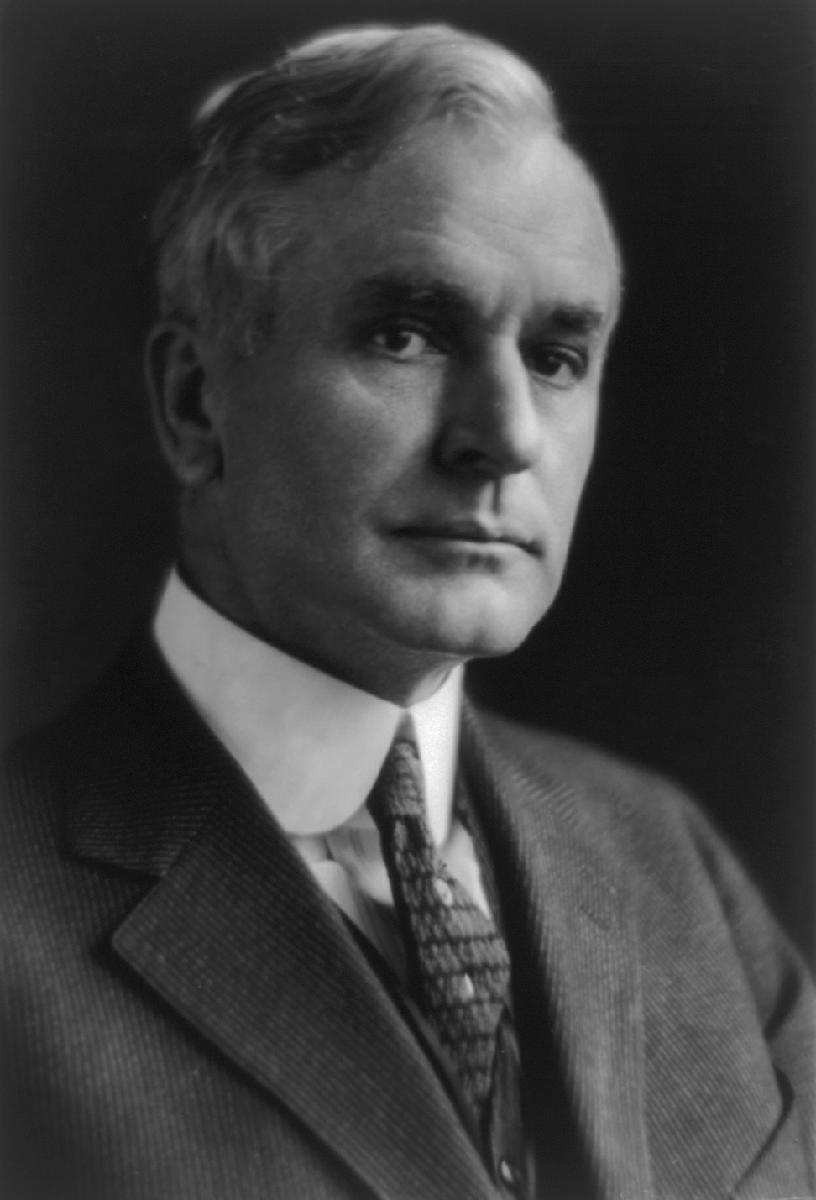

Paul Reynaud - French Prime

Minister - March - June 1940

French General Maurice

Gamelin

French General Maxime Weygand

- 1940

The French had built a very strong line of defense along France's border with Germany:

the "Maginot Line."

But the Germans simply swung to

the north around that line thorough the dense

Ardennes Forest in

Belgium ... and then came quickly down behind the forts, cutting off

French resupply and thus trapping French troops in their Maginot

fortifications. |

German Panzers advancing through the Ardennes Forest - May 1940

Fisher, p. 557

Battle of France

German troops moving through a village in France (June 1940)

|

Allied escape from Dunkirk and Cherbourg

With the Germans moving quickly to the West (they reached the Channel by May 20th) the situation facing the Allies was almost hopeless. Then on the 23rd the Germans made the decision to halt their advance and consolidate their position. Concerns were raised in Berlin that this would allow the Allied armies the opportunity to escape the trap ... though German Air Marshall Hermann Göring assured Hitler that the Luftwaffe would prevent any such escape if the Allies attempted it. But on May 26th Churchill called on every available ship, fishing boat – anything that floated – to head to the Belgian port of Dunkirk to help rescue the Allies from the German encirclement. Fortunately for the Allies, the Luftwaffe was slow to respond ... and renewed French action to the south at Lille drew German troops away from the German position around Dunkirk. This allowed over the next days (May 26-June 4) some 338 thousand French and British troops to escape to England. There were serious losses from Luftwaffe airstrikes, but the Royal Air Force (RAF) put up a stiff resistance ... helping immensely in the operation. Some two weeks later another huge group of Allied troops (some 200 thousand) were rescued from the Brittany peninsula at Cherbourg ... though this time with a much larger loss of Allied lives (4,000) in the operation. |

A trapped British Expeditionary

Force and thousands of French soldiers make their escape

from German encirclement

at Dunkirk (May 27 - June 4)

British troops escaping from

Dunkirk (France, 1940).

Screenshot taken from the 1943 United

States Army propaganda film Divide and Conquer

(Why We Fight #3) directed by

Frank Capra and partially based on news archives, animations,

restaged scenes and captured propaganda

material from both sides.

British and French troops

awaiting evacuation from Dunkirk

Some of the 200,000 British

and 140,000 French and Belgian soldiers

during a 10-day evacuation

from the beach at Dunkirk, Belgium - late May/early June1940

Evacuated British troops

looking back at the port of Dunkirk

Imperial War Museum

Escaped British troops arriving home at Dover

Some 40,000 troops remained behind to provide cover for the rest (one in seven of the troops)

and were eventually overrun by the advancing Germans, and led off to prison camps

British and French prisoners

at Veules-les-Roses, France, June 1940

National Archives

242-EB-7-35

|

The Fall of France (mid-June)

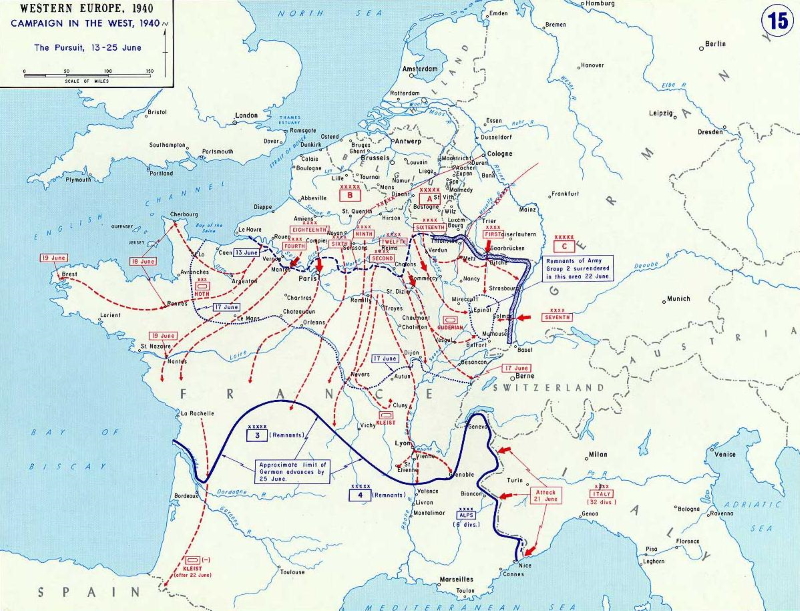

But at this point it was all but over for the French. The French were defending a broad but thinly held front, unable to move quickly to meet German attacks because of the millions (six to ten million by some estimates) of civilians crowding the roads trying to get away from the fighting. The Germans on June 5th resumed their attack to the south towards Paris. By June 10th they had reached the suburbs of Paris. Then Mussolini decided to become the great warrior he believed himself to be and declared war on France and Britain (also June 10th), and invaded southern France ... making little headway in the attack. On June 14th French troops – not wanting to see Paris destroyed in a hopeless defense of the city – pulled out of Paris, leaving it entirely in the hands of the German army. The French continued to fight on in the East behind the Maginot Line, but one by one French army units were forced to surrender, most of them by June 25th. For France the war was over. Vichy France

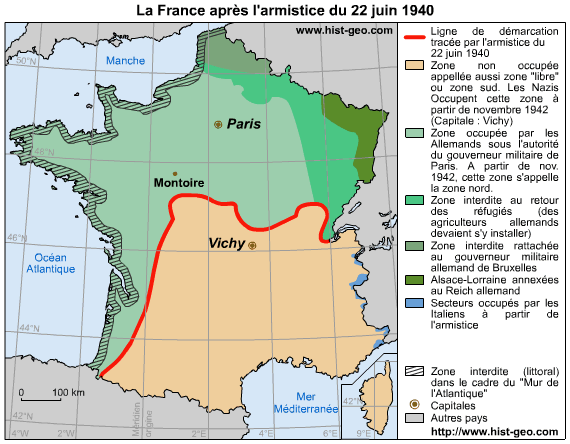

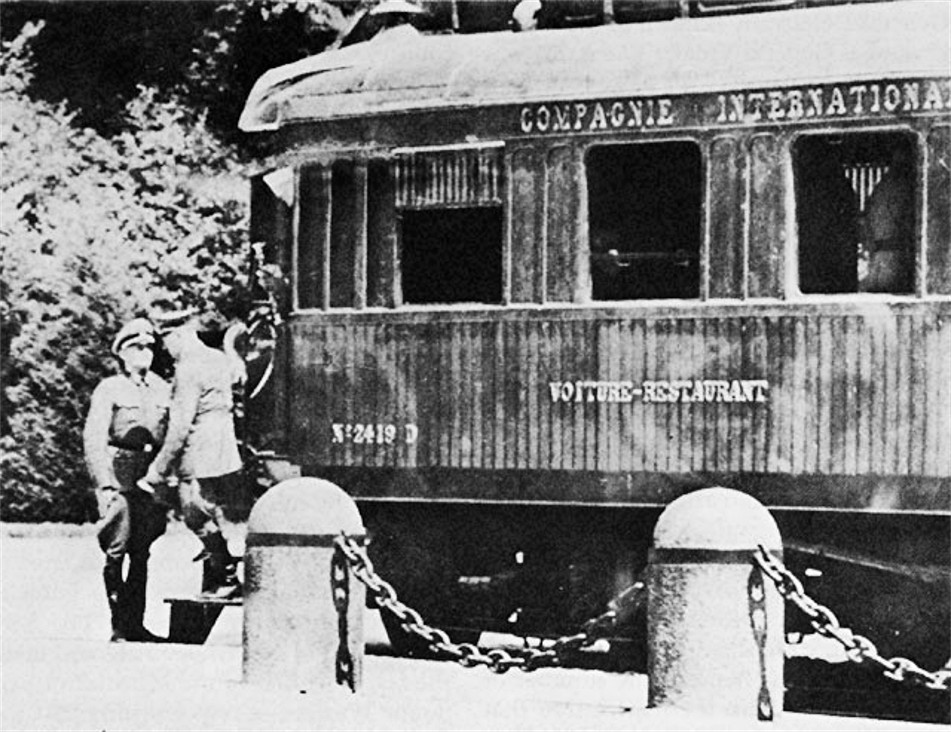

Realizing that his French cabinet (which had retreated south to the city of Tours) had lost the will to fight on, on June 16th Reynaud resigned (or was forced to resign) ... and the World War One French hero, Marshall Philippe Pétain, took over as prime minister. He agreed to meet with Hitler to sign an armistice ... and Hitler designated the meeting to be held on the 22nd in very same railroad car (serving as a French monument in the Compiègne Forest) where the Germans had signed the Armistice forced on them in 1918. For Hitler personally, this was major payback. Fighting was designated at Compiègne to end on June 25th. France was then divided into two zones, one in the north (including Paris and most of France’s industrial territory) under direct German administration, and one in the south under a new French government operating out of the resort town of Vichy ... headed by Pétain. The Germans allowed the Vichy government to keep its overseas colonial territories and a small portion of its navy for defense of those colonies ... and in theory full sovereignty within its zone so that life could supposedly go on as it was before the war. Also some two million French soldiers remained as forced labor prisoners in German-occupied Europe ... and as hostages ensuring Vichy compliance with the terms of the Armistice. Then gradually Pétain’s Vichy government itself took on a stronger fascist tone, becoming virulently anti-Jewish ... and after Hitler’s invasion of Russia in June of 1941 virulently anti-Communist. But General De Gaulle had refused to recognize any form of French surrender – as per his BBC speech from London on June 18th – and likewise rejected entirely Pétain’s Vichy government. De Gaulle then began to organize a Free French Army and a French government-in-exile in London (Reynaud had been arrested by the Germans and was not a participant in the London government). But for the time being, there was actually little that the French could do about their situation. |

The Fall of France - June 1940

Department of History, United

States Military Academy

French fleeing south to escape the German offensive - 1940

Belgians fleeing west along the Louvain-Brussels road to British held territory - May 1940

Imperial War Museum

Germans on parade in front of Belgium's Royal Palace in Brussels - 1940

German Federal Archives

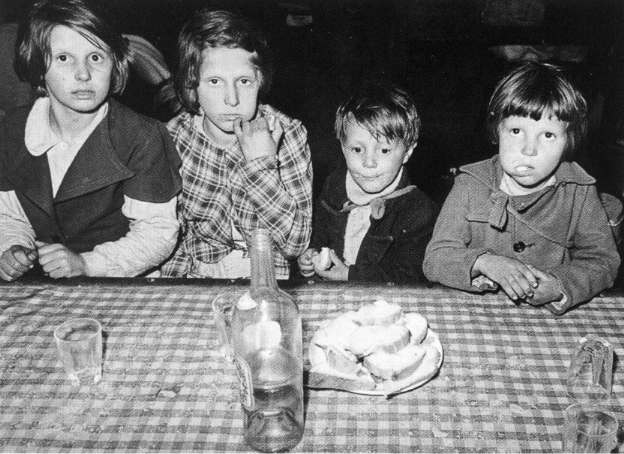

Belgian refugee children

- summer of 1940

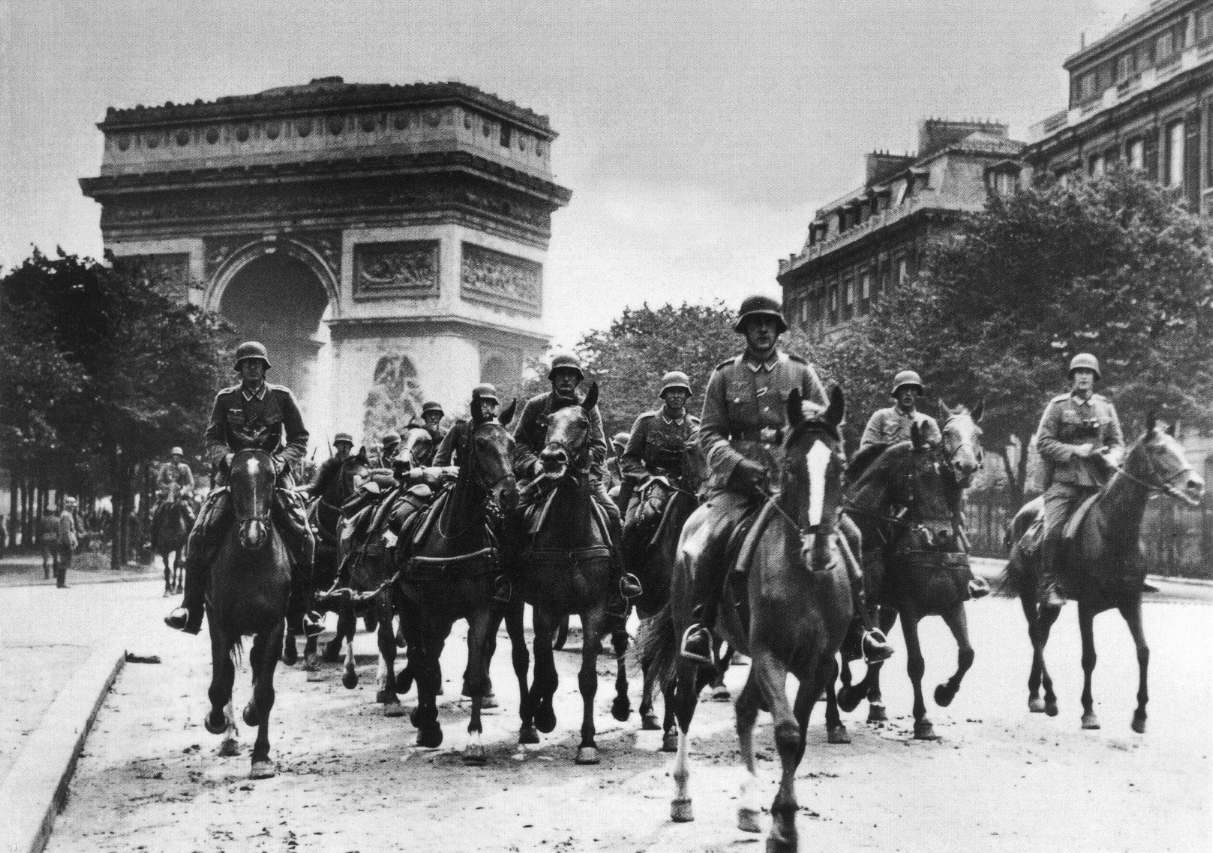

German horsemen parading

triumphantly past the Arch de Triomphe in Paris - June 1940

"A Frenchman weeps as German soldiers

march into the French capital,

Paris, on June 14, 1940, after the

Allied armies had been driven back across France"

National Archives

208-PP-10A-3.

Hitler strolls through the

Paris his troops have conquered for him – July 1940

Adolf Hitler in Paris, June 23, 1940

National Archives

242-HLB-5073-20.

Adolf Hitler leaving the

railway carriage in which the armistice was signed at Compiègne

German occupied France

… and Vichy France

Wikipedia - "Battle

of France"

Pétain, Head of the

Vichy Government, shaking hands with Hitler - October 24, 1940

Deutsches Bundesarchiv

|

| Only

the offshore island of Great Britain remained unconquered in the

West. At first Hitler had expected a British request for an

armistice ... and planned to be ‘generous’ in the negotiations. But

when in his famous "finest hour" speech before Parliament on June 18th

Churchill made it again clear that even with the fall of France, he

refused to consider any notion except total victory in this war, Hitler

became determined to bring Britain as well to humiliating defeat.

Operation Sea Lion was thus birthed in Hitler’s mind. But he had no idea how difficult a Channel crossing might be ... and how unready his German troops were for such a venture. He himself believed that an invasion of Britain could bring Britain to its knees by mid-August. Thus (despite warnings from his generals) in July Hitler began his aerial bombardment of British convoys in the English Channel in preparation for his intended cross-channel invasion of that country. Then on the 12th of August the Germans hit radar installations on the English coast in preparation for the beginning of the bombing of England itself on the following day. Savagely he hit British airfields, docks, ships and industries. But the RAF fought back skillfully, as did the anti-aircraft gunners defending Britain from the ground. Consequently, the Luftwaffe’s losses were huge. Furthermore, downed German pilots became prisoners in Britain ... but British pilots could parachute out of a downed plane and return to action with a new plane. In any case the British showed no signs of yielding. As a huge gamble, on August 15th Hitler sent a force of a thousand planes to attack Britain, losing 180 planes in the process. Indeed, in a week’s time the Germans lost 492 planes to the RAF’s loss of 115 planes. Things clearly were not working out well for Hitler and his Operation Sea Lion. Then the British retaliated by sending bombers to Berlin on August 25th ... materially not a matter of great significance, but spiritually a devastating blow to Hitler’s Germany. This was the first time that the Germans had felt the effects of war on their own ground since the days of Napoleon. Hitler was furious. On September 7 Hitler shifted his attack from English airfields to London itself – more horrible in destruction – but a strategic distraction, foolishly sparing British Fighter Command at a time that the British were actually having a hard time replacing lost fighter planes. Finally, an air battle on September 15 - with huge German air losses – caused Hitler to postpone Operation Sea Lion to the following spring (1941). Nonetheless the "Battle of Britain" continued with widely spread German attacks on England’s cities and towns (with London receiving the worst of it). But this was a costly venture for the Germans, losing 2-to-1 in the downing of planes (July to October of 1940: 1733 German planes versus 915 British planes downed). It was now the turn of the British to send bombers to Germany to destroy mines, factories, railroads, etc. in the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. In the meantime, while England was suffering a similar fate, the British were nonetheless finally beginning to produce significantly more fighter planes for the RAF. Then with the German invasion of Soviet Russian territory in June of 1941, the German air attacks on Britain dwindled. |

A Heinkel He 111 over the

East End of London during the Battle of Britain, 7 September 1940.

Imperial War Museum

German Junkers Ju 87B "Stuka"

dive-bombers

Aircraft spotter on the roof of a building

in London. St. Paul's Cathedral is in the background.

National Archives

306-NT-901B-3

Battle of Britain:

a fiery London wall collapsing

London bombed

National Archives

A result of German bombardment

of London during the "Battle of Britain" - summer of 1940

"Children of an eastern suburb of London,

who have been made homeless

by the random bombs of the Nazi night

raiders, waiting outside the wreckage

of what was their home." September

1940

National Archives

306-NT-3163V.

Residents of Plymouth, England,

reading the casualty lists

Winston Churchill whose mere

presence among the people encouraged them to hang on

against Germany

The London Underground as

an air raid shelter - summer 1940

Londoners in the Underground,

taking refuge from German bombing

"Standing up gloriously out of

the flames and smoke of surrounding buildings,

St. Paul's Cathedral is pictured during

the great fire raid of Sunday December 29th." 1940

National Archives

306-NT-3173V

Though Hitler's Invasion

of Britain is postponed indefinitely –

he continues his aerial

bombardment of England

Churchill surveys the damage

done to British Parliament by German bombers – May 1941

"Two bewildered old ladies stand amid

the leveled ruins of the almshouse which was Home;

until Jerry dropped his bombs. Total

war knows no bounds.

Almshouse bombed Feb. 10, Newbury,

Berks., England." Naccarata, February 11, 1943.

National Archives

111-SC-178801

Columbia Broadcasting reporter

in London, Edward R. Murrow

who kept Americans

abreast of the stiff resistance of the British to the German attacks

during the "Battle of Britain"

(1940-1941) – as America officially stayed neutral

|

| When Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty in 1939, this seemed to

overturn the provisions of Germany’s earlier Anti-Comintern

(anti-Communist or actually anti-Soviet) Pact with Italy. Hitler

resolved this issue with a new Tripartite or "Axis" Pact signed in

Berlin on September 27, 1940, by Germany, Italy and Japan. This not only gave considerable encouragement to Japan's imperial ambitions in Asia (at the expense of the English, French and Dutch and to the great irritation of America) - it put Germany on record as willing to come to war as a Japanese ally if war should occur between Japan and America. With the signing of the Tripartite Pact, the "Rome-Berlin Axis" now officially included also Tokyo - and the world now acknowledged those belonging to this military alliance as the "Axis Powers." |

Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler in

Munich, Germany, ca. June 1940

photo by Eva Braun

The term "Axis Powers" formally

took the name after the Tripartite Treaty was signed

by Germany, Italy and Japan

on September 27, 1940 in Berlin, Germany.

Axis Powers signing with Saburo Kurusu

(Japan's Ambassador to Germany),

Galeazzo Ciano (Italy's Foreign Minister)

and Fuhrer Adolf Hitler.

Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany

toasting the Axis Pact in Tokyo, Japan.

Here officials of both powers are present

including Prime Minister Hideki Tojo

and Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka.

|

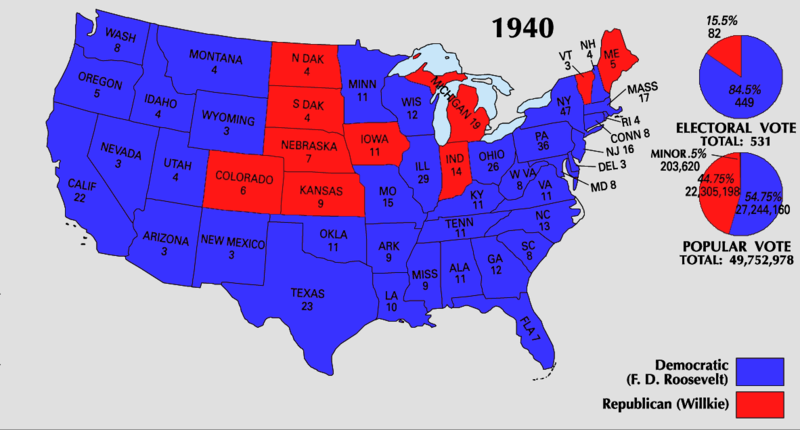

| American

neutrality was a bit of a fiction – maintained by both sides of the

European contest. Sensing the growing danger of war, America

increased its defense budget from $2 billion to $10 billion in 1940 and

established its first peacetime military draft. Likewise its

economy was highly dependent on industrial sales abroad … most of that

destined to Britain – France now knocked out economically and Germany

being as industrially self-reliant as possible. Hitler responded

by pushing his U-boats to cut off the shipping going on between America

and Britain – at least that portion conducted by British carriers –

whose boats the Germans were sinking faster than the British could

replace them. Yet using its own carriers, America was able to increase its trade with Britain enormously – such as the millions of rounds of "surplus" ammunition it sent to Britain. Then there was the matter that same September of America turning over to the British some 50 of its "mothballed" navy destroyers … in exchange for land rights offered by the British, ones allowing America to build numerous airbases within Britain's Empire. Then also, Roosevelt announced in December that America was to be the "Arsenal for Democracy" and would thus be selling war materiel quite openly (to Britain obviously) in protection of the world’s democracies against the recent rise in authoritarianism globally. This was hardly the policy of a "neutral" nation. But Roosevelt had to proceed very cautiously, for there were numerous citizens (and congressmen) very isolationist in attitude … committed fully to keeping America out of another European war … no matter who the victor might be. But this group was losing out to a growing attitude within America that Western civilization itself was in great danger of being destroyed by Europe's (and Asia's) rising Fascism … and that it was America’s responsibility to see that this should never happen. "Lend-Lease"

The next year, 1941, Roosevelt was even able to get Congress (the majority Democrats at least, for most Republicans remained quite isolationist) to pass his "Lend-Lease" legislation. This authorized the president to sell, transfer title, exchange, lend, or lease to any government anything that he deemed strategically necessary to the defense of America. This therefore put America in full partnership with Britain. But it would soon also include China and Russia as well. Finally, America went all out in repealing in October the last of the Neutrality Acts, ones that had been passed every year since the mid-1930s. And American merchant ships were now authorized to be fully armed … and also to actually transport the war materials that had been going to Britain formerly only by British ships. Clearly, America’s “neutrality” was pure fiction. But Hitler, a very busy man at the time (deeply caught up in his new war with Russia) chose still to ignore this American change in status. |

FDR discusses with the press

the situation in Europe - 1939

Roosevelt stands for election

to his third term as President

Issues deciding the election

are national rather than international –

the Depression being the biggest

matter of interest to Americans

He is returned to office with a very large showing of national support

Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt

on his way to his 3rd inauguration in January of 1941

National Archives

Roosevelt's "Brain Trust" as America faces the possibility of war

Roosevelt's personal advisor

Harry L. Hopkins as he leaves for England - January 1941

New York World-Telegram

and the Sun - Library of Congress

Cordell Hull - Secretary

of State (1933-1944)

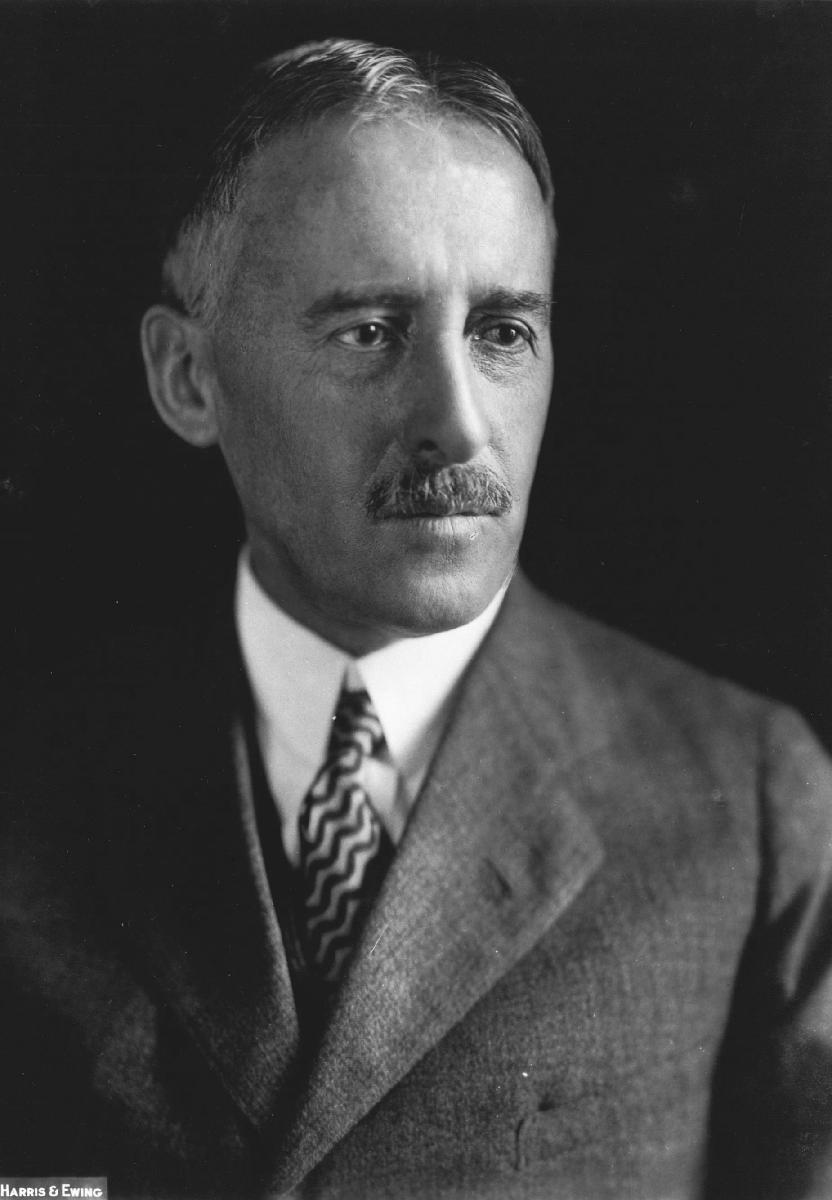

Henry L. Stimson, Secretary

of War (1940-1945; but also 1911-1913)

and Secretary of State

(1929-1933)

Harris & Ewing

With Hitler's surprise invasion of Stalin's Russia (Operation Barbaross) in June of 1941

the American position hardens against Hitler

Harry Hopkins meets with

Stalin in August 1941

to investigate the possibilities of working together against Hitler

Margaret Bourke-White -

LIFE

|

Churchill is determined that the French fleet located in North Africa not fall into Hitler's hands

Churchill's Sinking of the

French Fleet (July 3, 1940)

Scott Manning - November

29, 2006

On July 3, 1940, Royal Navy

warships shelled their French counterparts

at the Algerian port of

Mers-el-Kebir

The Italian Battleship Cesare

firing her salvoes near Punta Stilo (Battle of Calabria) - July 1940

Ministero Della

Difesa-Marina

The Battle for Crete - May 1941

German paratroopers jumping

from Ju 52s over Crete - May 1941

Imperial War Museum

German paratroopers over Crete

|

The Scharnhorst and U-47

German submarine

An aerial view of a convoy

escorted by a battleship during the Battle of the Atlantic.

The ships stretch as far

as the eye can see. April 1941

Imperial War Museum

Officers on the bridge of

a destroyer, escorting a large convoy of ships keep a sharp look out

for

attacking enemy submarines during the Battle of the Atlantic – October 1941

Imperial War Museum

US plane patrolling an American

convoy headed toward South Africa - November 1941

US Navy

| "Convoy WS-12: Vought SB2U scout bomber from USS Ranger (CV-4) flies anti-submarine patrol over the convoy, while it was en route to Capetown, South Africa, 27 November 1941. The convoy appears to be making a formation turn from column to line abreast. Two-stack transports in the first row are USS West Point (AP-23) -- left --; USS Mount Vernon (AP-22) and USS Wakefield (AP-21). Heavy cruisers, on the right side of the first row and middle of the second, are USS Vincennes (CA-44) and USS Quincy (CA-39). Single-stack transports in the second row are USS Leonard Wood (AP-25) and USS Joseph T. Dickman (AP-26)." |

|

| Another

piece in the American move away from neutrality to active participation

in the huge conflict going on in Europe and elsewhere was an agreement

(soon termed the "Atlantic Charter") negotiated by Churchill and

Roosevelt at a secret meeting in mid-August aboard a British warship

anchored offshore from Newfoundland.1 This agreement outlined a vision for a post-World-War-II world, despite the fact that America had not yet entered the war. In brief, the eight points of the Atlantic Charter were: 1. no territorial gains sought by the United States or the United

Kingdom; 2. territorial adjustments must be in accord with wishes of the people; 3. the right to self-determination of peoples; 4. trade barriers lowered; 5. global economic cooperation and advancement of social welfare; 6. freedom from want and fear; 7. freedom of the seas; 8. disarmament of aggressor nations, postwar common disarmament At a subsequent Inter-Allied Meeting in London on September 24, 1941, the governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia, and representatives of General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, unanimously adopted the Charter. This agreement proved to be one of the first steps towards the formation of the United Nations ... including the use of the "United Nations" as the name of the grand alliance of those countries which joined together to fight the Axis Powers. 1Official statements and government documents imply that Churchill and FDR signed the Atlantic Charter. Actually, no signed copies are known to exist. A British writer, H V Morton, who traveled with Churchill's party on the Prince of Wales, states that no signed version ever existed. The document was thrashed out through several drafts, says Morton, and the agreed text was telegraphed to London and Washington. The British War Cabinet replied with its approval and a similar acceptance was telegraphed from Washington. |

Winston Churchill aboard

HMS Prince of Wales off Newfoundland

at the time of the Atlantic

Charter meeting with Roosevelt

Library of Congress

HMS Prince of Wales

off Argentia, Newfoundland, after bringing Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

across the Atlantic to meet

with President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Photographed from USS Augusta

(CA-31).

Donation of Vice Admiral

Harry Sanders, USN(Retired), 1969

U.S. Naval Historical Center

Photograph

|

USS McDougal

(DD-358) alongside HMS Prince of Wales, to transfer President Franklin

D. Roosevelt to the British battleship for a meeting with Prime Minister

Winston Churchill. Photographed in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland

Donation of Vice Admiral

Harry Sanders, USN(Retired), 1969

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph |

|

British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill meets with President Franklin D. Roosevelt on board USS

Augusta

(CA-31), off Argentia, Newfoundland, August 9, 1941. Assisting

the President is his son, Army Captain Elliot Roosevelt. Ensign Franklin

D. Roosevelt, Jr., USNR, is at left, with Assistant Secretary of State

Sumner Welles standing behind him.

US Naval Historical Center

photograph

|

|

Church service on the

after deck of HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland,

during the conference. Seated in the center are President Franklin

D. Roosevelt (left) and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Standing

behind them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN (between Roosevelt and Churchill);

General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army;

Admiral Harold R. Stark, USN; an

Donation of Vice Admiral

Harry Sanders, USN(Retired), 1969.

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. |

FDR and Churchill worshiping

together aboard the Prince of Wales

Standing directly behind

them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall,

U.S.

Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army;

Admiral Harold R. Stark,

USN; and Admiral

Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins,

talking with W. Averell Harriman.

U.S. Naval Historical Center

Photograph #: NH 67209

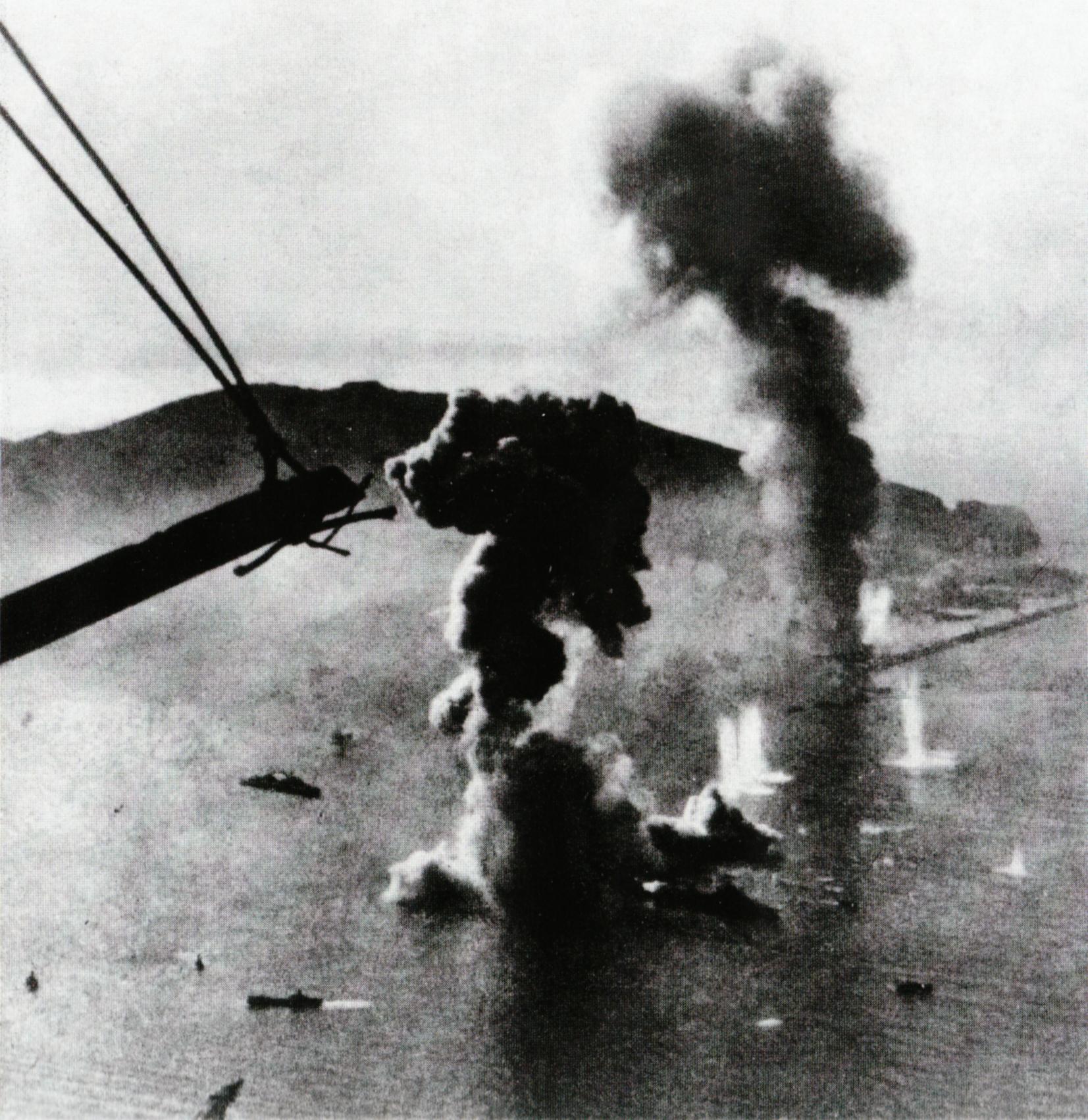

(Four months later, on December

10, 1941, Japanese dive bombers would sink

the mighty Prince of

Wales, and send her captain,

and many officers and sailors to their

deaths.)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Library

Roosevelt and Churchill on the Prince of Wales after the signing of the Atlantic Charter - 1941

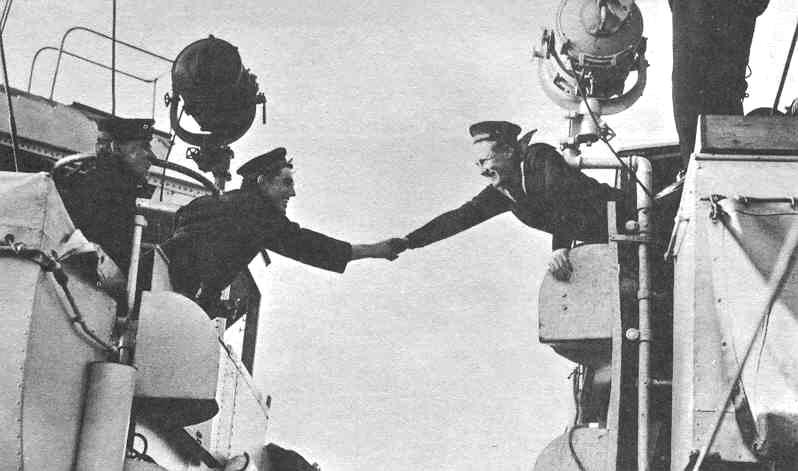

British sailors congratulating

each other for having brought over

2 of 50 "mothballed" American

destroyers

Winston Churchill's edited copy of the final draft of the

charter

Go on to the next section: America and Russia Are Dragged into the War

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges