|

|

Alexander III (1881-1894) Alexander III (1881-1894) Jewish persecution Jewish persecution Problems on the peasant farms Problems on the peasant farms Nicholas II (1894-1917) Nicholas II (1894-1917) Rapid social change Rapid social changeThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 57-59 |

|

| With the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in

1881, the new Tsar Alexander III would bring Russia into a period of

reaction (Alexander III was completely opposed to the liberal reforms

of his father Alexander II) ... something on the order of Nicholas

I. Nicholas's almost forgotten doctrine of "autocracy, orthodoxy

and nationality" would be revived by Alexander III ... perhaps even

more rigorously. To the new Alexander, anyone who did not honor

the absolute power of the Tsar and was not Russian Orthodox in religion

and Russian in language and culture was suspect in the tsar’s

eyes. He despised the internationalist mindset of the Russian

liberals, and did what he could to crush the spirit of Russian

liberalism. His dedication to the cultivation of the Russian nationalist spirit was fierce. For an empire built on many different nationalities and ethnic groups this would be a hard thing indeed. The Finns and Poles, for instance, who had earlier been promised co-equal status within the empire, would see their cultural-political rights removed one by one. Yet these very actions by Alexander would serve to increase the cultural sensitivities of the subject nations, not bring them to the point of assimilation into the larger Russian culture. |

Tsar Alexander III (reigned

1881-1894) by Ivan Kramskoi - c. 1886

The coronation of Tsar Alexander

III and Empress Mariia Fyodorovna (Princess Dagmar of Denmark)

at the Upensky Cathedral

of the Moscow Kremlin, 1883

Portrait by Georges

Becker

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg,

Russia

Tsar Alexander III (reigned

1881-1894) by Nikolay Shilder

Brown Brothers

Maria Fjodorovna and Alexander

III of Russia on vacation in Copenhagen 1893

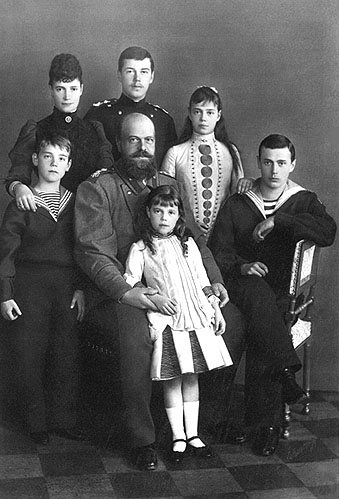

Alexander III and family

|

| The worst-case scenario was that of the Jews

in Russia ... where more than half of the world’s Jews lived by the

late 1800s. Jews had been brought under Russian dominion during

the reign of Catherine the Great, with the second and third (1793-1795)

partitions of Poland, where in Eastern Poland (at this point now

absorbed into Russia as its Western region) there were numerous

German-speaking Jewish settlements. Catherine then set out the

boundaries of a "Pale of Settlement" to which Jews were

restricted. Under Nicholas I, the restrictions against Jews

serving in the military were finally lifted ... and indeed Jews were

required to perform military service under Nicholas's 1827 conscription

law. Gradually Russian Jews began to adopt Russian ways and under

Alexander II were even freed up (along with the ending of serfdom in

1861) to the extent that many began to enter the ranks of the Russian

upper middle class of merchants and intellectuals. When the reactionary Alexander III became tsar in 1881, the situation facing the Jews became harsh. Jews were falsely blamed for Alexander II’s death ... and a mass of anti-Jewish "pogroms" (the random beatings of Jews and the plundering and burning of their homes) broke out across the south of Russia ... continuing until 1884, when the Russian "Christians" were finally satisfied, as a new round of anti-Jewish laws went into effect. Jews were forced to abandon their farms and move into towns and cities ... then expelled from even some of these such as Kiev in 1886 (and Moscow in 1891). In 1887 highly restrictive quotas were placed on Jewish entrance into secondary and higher educational institutions and into a number of professions, particularly the legal profession. In 1892 restrictions were added prohibiting the Jews from voting or holding elective office. Then a new wave of pogroms hit the Jewish community in the period 1903-1906. Thousands were killed or gravely wounded in the ordeal. Meanwhile Jews were emigrating from Russia in mass numbers ... most of them to America, and some to other parts of Europe. But some also began to migrate (1882 and after) to the region of Palestine within the Ottoman Empire ... as part of the new "Zionist" movement. |

|

| But the situation for the Russian

peasants was not all that wonderful either. They were easily

disillusioned when the formal end of serfdom did not bring about the

gains they were expecting. In some cases the new freedom brought

on economic hardships they were not accustomed to. Payments for

the land, land scarcity and the small size of the farmers' plots of

land, poor agricultural practices, and periods of bad weather made

success in their new "business" of farming at times almost

impossible. Thus peasant rebellions were constant and numerous in

the latter part of the 1800s. |

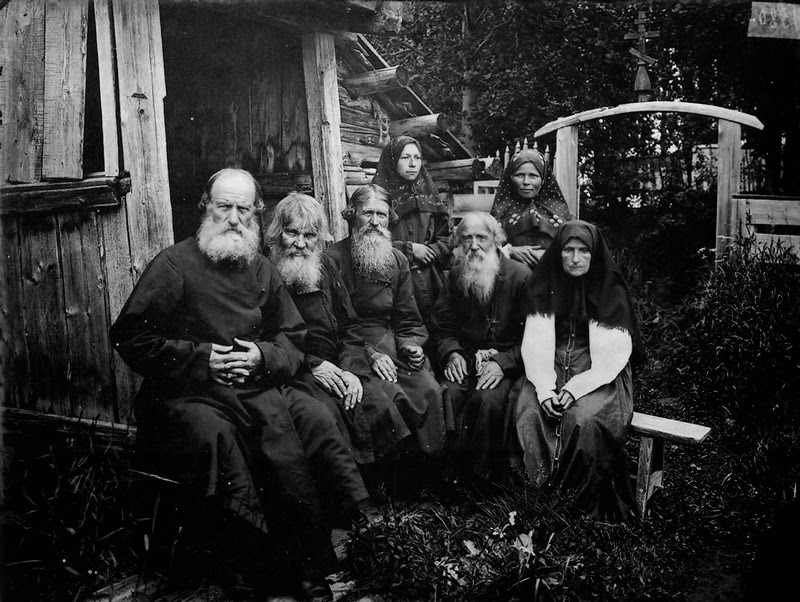

Life for the rest of Russia

Peasant street vendors in Moscow

Food shopping in a village

Making baskets

Village social life

A village celebration

|

| When Nicholas come to the throne after his father’s sudden death there was hope that he would return Russia to the path of liberalization started by his grandfather Alexander II. That hope would soon fade away. Although Nicholas was not the suspicious reactionary that his father was, he had the very strong conviction that he was placed on the throne to serve God by preserving the old Russian order ... against the modernizing tendencies of the liberals. Worse, he was easily manipulated by stronger personalities around him ... especially by his wife who possessed even stronger, virtually mystical, convictions that they were placed on the throne to carry out the will of God ... not the will of man. |

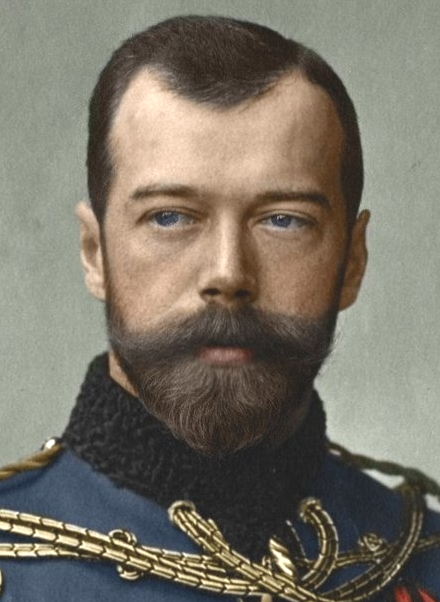

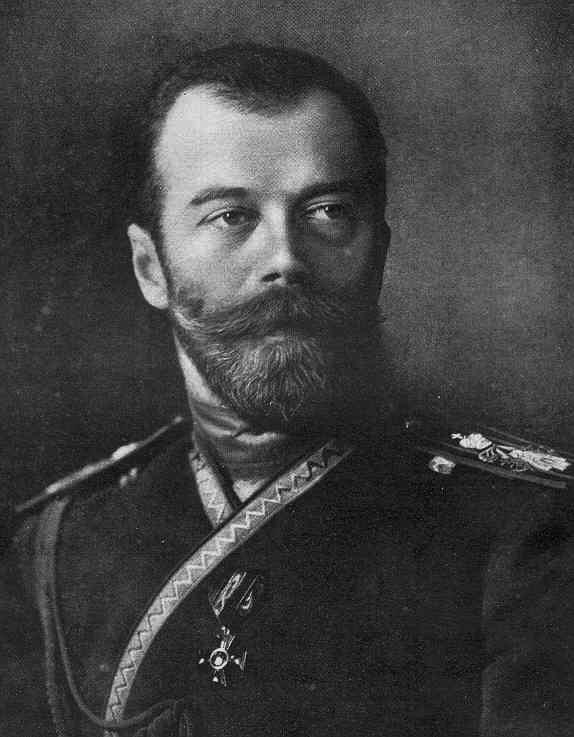

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia

(reigned 1894-1917)

Nicholas II

Empress consort of Russia

(Tsaritsa) Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse)

Library of Congress

Nicholas II with his wife,

four daughters and son (1910)

Deutsches Bundesarchiv

|

| Meanwhile liberalism was spreading within a

growing population of educated Russians ... desiring Russia to be

recast as a constitutional democracy on the model of Great

Britain. Behind this growth was the slow emergence of the

industrial revolution in Russia ... and the new wealth it was creating

among the small upper middle class of "capitalists." But this

group by comparison to the rest of Europe would remain tiny – and

relatively politically incoherent (organizing themselves into a large

number of small competing political parties). They also would

never gain the economic leverage that this class had in the rest of

Europe because most of the investment and industrial development came

not out of their finances but rather from foreign investors ... and the

Romanov state ... which owned most of the newly accumulating industrial

wealth of Russia. This same industrial revolution was also producing another new and rising social class in Russia: the industrial worker. By the turn of the century this rapidly growing segment of Russian society was developing a very aggressive social and political agenda ... in great part because of that very fact that the companies they worked for seemed remote and insensitive to their needs ... being foreign and state owned. Consequently, a quasi-Marxist ideology despising both (foreign) capitalism and its supposed tool, the state, developed within the working class ... and among the intellectuals (in particular the Social Democrats – "or Communists") that felt called on to give voice to that working class. |

The Tsarina Alexandra and her children Alexei, Anastasia and Maria - 1908

Alexandra being greeted on the family's yacht - 1908

Moscow - 1910

High society in Moscow - 1909

The Russian industrial working class

(approximately 1900-1910)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges