|

|

Akkad

/ Babylon (2500 - 1000 BC) Akkad

/ Babylon (2500 - 1000 BC)

The

Sumerian / Babylonian world views The

Sumerian / Babylonian world views

The

Assyrian Empire (ca. 900 - 605 BC) The

Assyrian Empire (ca. 900 - 605 BC)

|

|

|

Sumerian society

Sometime prior to 5,000 BC, Sumerians moved into the region of the lower Tigris-Euphrates. We do not know where they came from: they were called Sumerians by their northern neighbors. Their language was not related to any other language known today. Many of the geographic names in Sumer seem to have been borrowed perhaps from previous inhabitants. Their contribution to the material basis of civilized life was awesome. We know that the Sumerians were early users of copper – perhaps as early as 5000 BC. By 4500 BC they were casting copper into molds to make various tools and art objects. Speculation is that they were the inventors of the potter's wheel. They also developed the animal-drawn plow. And they used sails on their boats to navigate the broad Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Also, they developed for war use a solid-wheeled chariot drawn by a now-extinct form of donkey. About 3300 BC they invented a pictographic form of writing to keep account of stored goods at these temples; they used reed ends, pressed into soft clay tablets (cuneiform), to make their recordings. Record-keeping evolved to include royal inscriptions (2700 BC) and new law codes (2100 BC, promulgated by Ur-Nammu, king of Ur). Early Social organization

They transformed their marshy and flood-prone habitat into a very productive region: canals and dikes regulated a constant supply of water for their agriculture feeding 10x the amount of people or livestock that rain-dependent plots could (three grain harvests a year). Date-palms required extensive planning (they do not bear fruit before 5 years of age). With this agricultural bounty, they could buy the metal and materials they themselves did not have at hand. Social cooperation was essential and leadership absolutely necessary for this venture to have succeeded. Each of the independent city-states that made up Ancient Sumer was headed by a priest-king who drew considerable authority and power from the city’s particular gods. Disciplined obedience was greatly enhanced by the fact that life outside of this created world was unthinkable, for only desert lay beyond the reclaimed world of Sumer. One had to remain in good standing within the community – for all life depended on it. Eridu (Uruk) was the southernmost and earliest settlement--along what then was the coast of the Persian Gulf. Other notable Sumerian towns (a dozen or so) were Ur, Nippur, Lagash, Umma, Kish. In about 2700 BC town walls were built at Eridu which were 18 feet thick and encompased an area 6 miles in circumference. At the center of their settlements they built temples--which added stories on top of stories: the ziggurat. The city of Ur eventually extended its political boundaries to form an empire which included Babylon: the Babylonian language came to be widely spoken throughout Ur. Sumerian civilization however, began a serious decline after 2500 BC--as it fell prey to its expansive neighbors and eventually became absorbed into their worlds. |

Sumerian ziggurat at Ur,

built around 2000 B.C.

The reconstructed ziggurat at Ur

An artist's reconstruction of the ancient city of Ur

Statue of Gudea, Prince of

Lagash (c. 2150 BC) diorite – from Tello (formerly Girsu)

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Sumerian steward Ibihil -

Mari, early 2000s B.C.

Standard of Ur – "peace"

side (c. 2500 BC) from a princely tomb in Ur

shells, limestone and lapis

lazula attached to wooden core with tar

London, British Museum

Beaker – Susa (modern Shush,

Iran) (c. 4000 BC) ceramic painted in brown glaze

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Goldern bull's head (with

lapis lazuli eyes) from the Royal Cemetery, Ur

Sumerian stone figures discovered

in a pit under the floor

of a temple at Tel Asmar

(on a tributary of the Tigris)

Statue of a Sumerian worshiper

(ca. 2600 BC)

Sumerian clay figures --

with eyes emphasized

(considered the windows

of the soul, the pathways of communication to the gods)

Iraq Museum

Priest Guiding a Sacrificial

Bull – Fragment of a mural painting (2040-1870 BC)

from the palace of Zimri-Lim,

Mari (modern Tell Hariri, Iraq)

Aleppo, Syria, National

Museum

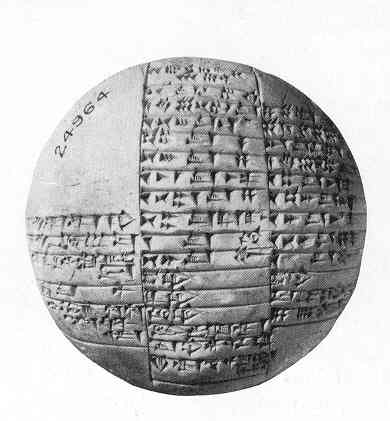

Sumerian cuneiform

writing

British Museum

|

|

The Sumerians and the Akkadians

The peoples immediately to the north of Sumer were a Semitic people, the Akkadians, who were strongly influenced by their close contacts with the Sumerians. (Akkadian Babylon was only 10 miles away from Sumerian Kish). For instance, Akkadians used Sumerian script in writing their own language. For a long time, the Sumerians refrained from extending their political control north to the Akkadians – and the Akkadians were long busy protecting themselves from desert nomads to the west and the mountaineers to the east – while they extended their own holdings northward along the river. Sargon of Akkad

Then in 2360 BC, Sargon (an Akkadian minister of the Sumerian king of Kish), starting from his own city of Agada near Babylon, began the conquest of Sumer. But he not only conquered his southern neighbors, the Sumerians, but he extended his political holdings from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean – as far north as Syria. But Sargon was a respecter of the Sumerian culture, which was loftier than his own Akkadian culture. Indeed, he incorporated what he could of Sumerian civilization into his Akkadian empire. This actually revived Sumerian civilization, and extended it further north along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This Akkadian-Sumerian civilization gave Mesopotamia a couple of centuries of peace. Hammurabi (ca. 1790 - 1750 BC)

Further to the north, and nearly 600 years later, from his base in the town of Babel (or Babil), another great king arose to conquer the larger Mesopotamian region. Very skilled at politics and diplomacy and taking advantage of the mutual hostilities of the other kingdoms and city states in the region, Hammurabi was able to extend Babylonian rule over the entire area in a gradual or step by step process. By 1760 BC a massive Babylonian Empire was well in place. Also, as he conquered Hammurabi extended a new regime of law and order that gave the region stability and a general prosperity that would make him famous to this day (It also made Babylon the largest city in the world from the mid 1700s to mid 1600s BC). So well considered was this Code of Hammurabi that it was adopted in one form or another by many surrounding societies – and when Babylon was itself later (ca. 1475 BC) conquered by the Kassites (who ruled Southern Mesoptamia for about four centuries) Hammurabi’s Code continued to be the legal foundation of the new Kassite Empire. |

Diorite head discovered at

Susa -- believed to represent King Hammurabi (2025-1594 B.C.?)

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Hammurabi receiving the Law

Code from the sun god Shamash.

The upper part of the stela of Hammurabis'

code of laws

Paris, Musée du Louvre

An inscription of the Code

of Hammurabi

The upper part of the stela of Hammurabi's

code of laws

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Hammurabi receiving the Law

Code from the sun god Shamash.

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Babylonian Boundary Stone

|

| Mesopotamian

religion took on a character which was more complex than neolithic

religion. The common people continued to observe locally the

neolithic fertility religions that seemed so vital to their

agricultural life. But the imperial structure that presided over

the larger social order that they enjoyed had to be "nurtured" by a

loftier set of religious ideas. The kings and priests had a special role in interceding for the whole empire before the major gods (eventually principally Marduk) who guarded the imperial enterprise. These gods were cosmic, universal – representing the organizing power of the universe, as their empires on earth represented a new organizing power among the people. Not surprisingly, given their importance in the scheme of things, the kings (or king/priests) came themselves to be regarded as semi-divine or even divine beings. The Epic of Gligamesh

Between 2700 and 2100 BC a vast literary tradition developed in Sumer, one which left a permanent imprint on the peoples around them and after them. For instance, The Epic of Gilgamesh (middle of the 3rd millennium BC) became the forerunner of the Genesis account of the Great Flood. The gods sent the Flood to punish people who had made them angry with their disobedience. But they warned the faithful Utnapishtim to build a boat, thus saving only him and his family. All the rest of humanity perished. The human race was begun again through his family. Also, their stories of their God Marduk were picked up by surrounding civilizations. The Enuma Elish

At the center of the religious life of the Babylonian culture which replaced Sumerian culture was the New Year's Celebration – held in April. This involved a number of events: the enthroning of the king for another year, the killing of a scapegoat as a sign of the death of the old year, and the reciting of the Enuma Elish (composed as we have it today perhaps around 1500 BC – though undoubtedly much older as a tradition). The Enuma Elish was a great epic story about creation: about how the gods were created to bring order out of the watery chaos. They were related to the "waters." There was Apsu: the good waters of the rivers Tiamat: his wife (the briny sea) Mummu: the womb of chaos They in turn gave birth to other gods (through the process of emanation) to complete the array of a world of definable sky and land, rivers and sea. This offspring rose up against their parents – though Tiamat proved to be difficult. But Marduk, offspring of the offspring, as Sun God, took up to fight for the gods under the provision that he should become their ruler. Only under very difficult circumstances was Marduk finally ably to slay Tiamat. Out of her corpse or womb (split into two parts) Marduk created a new world order: sky and earth. He also enunciated laws to bring order to this new creation – [though these laws had to be renewed in their strength every year through the performance of necessary rituals at the ziggurat of Marduk at Babylon]. He then created man by killing Tiamat's consort, Kingu, and mixing his blood with dust, making him half divine and half of the world. |

|

| In

the region of Northern Mesopotamia, up into the mountains from which

the Tigris River originated, a new power began to emerge around 900

BC. Unlike the expansion of Babylonian power under Hammurabi, the

expansion of Assyrian power (which began in earnest in the early 800s

BC under Ashurnasirpal II) proceeded through cruel violence waged

against Assyria’s enemies. Surrounding societies brought to

defeat by the Assyrian war machine typically had their cities destroyed

and the population either slaughtered or resettled as enslaved people

into different parts of the growing empire, where so scattered as a

people they would be no trouble to their Assyrian masters. By

such means they were able to subdue not only down to the northern

reaches of Babylon but also westward to the Mediterranean at

Syria. Then Assyria went into a period of decline due to the

succession of rather poor rulers. By the mid 700s BC Assyria was caught

up in massive internal strife. The seizing of the throne in 745 BC by an Assyrian general who took the name Tiglath-Pileser III restored Assyria to unity and administrative efficiency – reestablished the grip of Assyria over what had become a greatly weakened empire and set Assyria off in a new round of conquest – including Israel. Assyrian aggressiveness and violence meant that the Empire was maintained only by cruel force, which was hard to maintain, given the murderous infighting that occurred among the Assyrian leaders themselves. Revolts of subject peoples were frequent – usually only bringing a brief period of relief before another Assyrian king would reestablish Assyrian rule and punish severely these rebellious subjects. The northern kingdom of Israel experienced such wrath (721 BC) as did the city of Babylon (689 BC). So ruthless and dedicated to domination were the Assyrians that eventually their path of conquest extended all the way to Egypt (671 BC). But this policy of rule by ruthlessness exacted a great price in the way it chipped away at Assyrian power and left the Empire always under the threat of rebellion by one or another of its unhappy subject peoples – and often their local Assyrian governors (frequently the sons of Assyrian kings, impatient in their wait for their turn to rule the Empire). Finally with death in 627 BC of the last great Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian grip weakened and the Empire began to disintegrate. Scythians and Medes began to roll back the Empire in the East (the Medes even sacking the capital Nineveh in 625 BC) – and Babylon, reviving politically under the Chaldean leader Nabopolassar, once again rose up in rebellion in the South, the Babylonians burning Nineveh to the ground in 612 BC. For a time the Egyptians gave aid to the Assyrians, helping to put down a Jewish rebellion at Megiddo (or Armageddon) in 605 BC. But in that same year the Babylonians under Nabopolassar’s son Nebuchadrezzar met the combined forces of Egypt and Assyria at Carchemish and thoroughly routed them. This brought the Assyrian Empire to an end. |

The Jewish King Jehu bowing

to the Assyrian King Shalmanese III - 841 BC

Tiglath-Pileser III — stela

from the walls of his palace (ruled 745–727 BC)

British Museum

Assyrian bas-relief stone

carving showing an assault on a town with a siege engine

and the impaled enemies

of Assyria, c. 730 B.C.

British Museum

Sargon II (ruled 722 - 705

BC) and dignitary

Low-relief from the L wall

of the palace of Sargon II at Dur Sharrukin in Assyria

(now Khorsabad in

Iraq), c. 713–716 BC.

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Lamassu (Human-headed winged

bull) -- Sargon II's palace at Dur Sharrukin

ca. 716 - 713 BC

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Deportation of the Israelites

by the Assyrians (last third of the 700s BC)

| Shalmaneser V died suddenly in 722 BC while laying siege to Samaria, and the throne was seized by Sargon, the Tartan (commander-in-chief of the army), who then quickly took Samaria, effectively ending the northern Kingdom of Israel and carrying 27,000 people away into captivity into the Israelite Diaspora. |

Relief from Assyrian capital

of Dur Sharrukin, showing transport of Lebanese cedar (700s BC)

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Assyrian warship, a bireme

with pointed bow, 700 BC.

British Museum

Sennacherib (or Taylor)

Prism (ruled 705 - 681 BC)

The Oriental Institute,

Chicago

|

Column 4 (lines 8 - 49)

"I approached Ekron and slew the governors and nobles who had rebelled, and hung their bodies on stakes around the city. The inhabitants who rebelled and treated (Assyria) lightly I counted as spoil. The rest of them, who were not guilty of rebellion and contempt, for whom there was no punishment, I declared their pardon. Padi, their king, I brought out to Jerusalem, set him on the royal throne over them, and imposed upon him my royal tribute. "As for Hezekiah the Judahite, who did not submit to my yoke: forty-six of his strong, walled cities, as well as the small towns in their area, which were without number, by levelling with battering-rams and by bringing up seige-engines, and by attacking and storming on foot, by mines, tunnels, and breeches, I besieged and took them. 200,150 people, great and small, male and female, horses, mules, asses, camels, cattle and sheep without number, I brought away from them and counted as spoil. (Hezekiah) himself, like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem, his royal city. I threw up earthworks against him— the one coming out of the city-gate, I turned back to his misery. His cities, which I had despoiled, I cut off from his land, and to Mitinti, king of Ashdod, Padi, king of Ekron, and Silli-b?l, king of Gaza, I gave (them). And thus I diminished his land. I added to the former tribute, and I lad upon him the surrender of their land and imposts—gifts for my majesty. As for Hezekiah, the terrifying splendor of my majesty overcame him, and the Arabs and his mercenary troops which he had brought in to strengthen Jerusalem, his royal city, deserted him. In addition to the thirty talents of gold and eight hundred talents of silver, gems, antimony, jewels, large carnelians, ivory-inlaid couches, ivory-inlaid chairs, elephant hides, elephant tusks, ebony, boxwood, all kinds of valuable treasures, as well as his daughters, his harem, his male and female musicians, which he had brought after me to Nineveh, my royal city. To pay tribute and to accept servitude, he dispatched his messengers." |

Ashurbanipal (reigned 669

– 627 BC)

The Oriental Institute,

Chicago

The destruction of Susa of

Elam by Ashurbanipal, 647 BC

Photo by Zereshk

|

Ashurbanipal boasts:

"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed...the treasures of Sumer, Akkad, and Babylon that the ancient kings of Elam had looted and carried away. I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their goods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devasteated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt." |

The Royal Lion Hunt - from

the North Palace Nineveh, 645-635 BC.

British Museum

|

| Throughout

the period of Assyrian domination the city of Babylon retained much of

its importance as a political center, with Assyrian kings typically

installing their sons in Babylon as regional governors. Babylon

seemed always on the ready to rise against Nineveh (the Assyrian

capital) whenever weakness afflicted Assyrian leadership. By 625

BC, under Nabopolassar, Babylon was effectively an independent

political entity and by 605 BC, under his son Nebuchadrezzar (II) – or

as the Hebrew Bible called him, Nebuchadnezzar – it was once again the

dominant power in the ancient Near East. Nebuchadrezzar II – 605-562 BC

Nebuchadrezzar

proved to be not only a very capable military ruler but also an

excellent political administrator. Under his 40+ year rule

Babylon once again achieved what was then an unprecedented level of

material success. He not only rebuilt a much devastated Babylon,

he went on to make Babylon a truly great urban wonder, completing a

lavish royal palace, building or rebuilding the city’s temples,

bridges, canals and aqueducts, erecting a new triple-layered city wall,

and constructing the famed Hanging Gardens. He also extended this

building program in one form or another to the rest of his new

far-flung Babylonian Empire.His military conquests and diplomatic alliances brought defeat to the Scythians to the North, the Egyptians, the Phoenecians and the kingdom of Judah in the West, and a political alliance with the new power to the East, the Medes. Of particular importance to our study, we note that in 597 BC he forcibly pacified Judah by carting its king and aristocracy off into captivity in Babylon – and then in 587 much of the rest of the upper and middle class when a rebellion broke out against the Babylonian dominance in Judah – events that would have long-lasting and very monumental side effects. But this Babylonian supremacy was not to last very long. A new power was rising in the Persian plateau to the East which in 539 BC would end this Babylonian supremacy: a united Medea-Persia under rule of the Achaemenid ruler Cyrus the Great. Nonetheless, as under the Assyrians, Babylon would continue to thrive as a great city, although once again in support of non-Babylonian rulers. |

An artist's reconstruction

of Babylon during the reign of the Chaldean King, Nebuchadnezzar

(605-562 B.C.) showing the

Ishtar Gate, rooftop gardens and (in the distance)

the ziggurat in honor of

Marduk

Oriental

Institute

Modern reconstruction of the Ishtar

Gate of Babylon

Lion – From the

Processional

Way, Babylon (c. 575 BC) glazed brick

Istanbul, Archeological

Museum

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges