|

|

|

|

The Greek Contribution

We look to the ancient Greeks for the beginning of what we have come to know as ‘Western culture.’ The Greeks were great thinkers. Although they had started out as much of the rest of the world with rather neolithic ideas about how events on earth were regulated by gods and goddesses in the heavenlies above (and in the depths of the earth below), some of them began to notice a high degree of order around them, one not so easily explained by the doings of rather human-like and human-acting gods and goddesses. Greek thinkers began to explore the possibilities of other things being the source of this order. Thus Greek philosophy was born. And thus the Greeks put Western culture on the road to intellectual and spiritual enquiry – one still very much part of Western culture to this day. And it all began so very long ago. From Chaos to Order

Greek culture had grown up in a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus, called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair – as witnessed in the sagas of Homer: the Iliad and the Odyssey. But by 700 BC, the poet Hesiod was describing an Olympic realm in which the gods themselves lived under a divine order – with Zeus as the presiding figure over this order. The Materialists

As time progressed, during the 600s and 500s BC, from Greek Southern Italy in the West to Greek Western Asia (modern-day Turkey) in the East, Greek thinkers or philosophers were reflecting deeply on this matter of a basic order underlying all creation. To Thales, Anixamander, Heraclitus and many others this order was noticeable – even obvious. But the source of this order was a mystery to these thinkers. They speculated that this order might be the product of the actions of a singular substance which undergirded all matter--such as fire, air or water. Those that sought an answer to this question by searching for such a single substance or material as the foundation of all creation we categorize as "materialists." These materialistic philosophers were early forerunners of our modern scientists – with this same tendency to look to the material order for answers to the structure and dynamics of the universe. Pythagoras

Pythagoras (mid-late 500s BC) whom we may remember as being an astute mathematician, took a different course. He was a mystic – deep into the Orphic mysteries. To him the geometric patterns which he discerned the world to be made up of were really religious formulas which opened up the deeper spiritual realities which lay beyond the immediately visible world! The Athenian Greats: Socrates, Plato and Aristotle

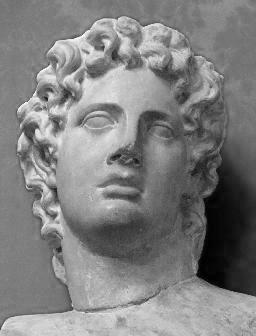

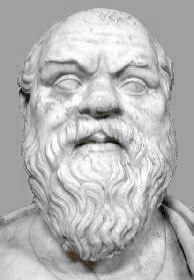

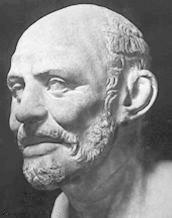

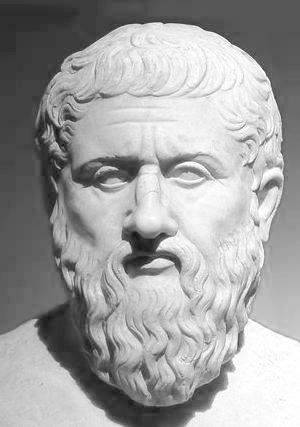

But it was three philosophers living in Athens during the 5th and 4th centuries BC – Socrates, Plato and Aristotle – who brought this sense of underlying order to full view for the Greeks. Socrates (mid-late 400s BC) was fully persuaded that the cosmos or universe was fundamentally an orderly place – every part of the great cosmos (including humans like ourselves – at least ideally) operating in accordance with a divine spirit of "justice" that flowed through all life, giving it purpose and structure. Moreover, human reason – when properly cultivated and judiciously applied to the study of this order – was capable of discovering the basic features of this divine order. Plato (early-mid 300s BC) was an Athenian pupil of Socrates who carried the thinking of his teacher even further. Plato sought to formulate the actual structure or nature of this divine order. He came up with the (quite Pythagorean) idea of Forms (or Ideas) as basic designs inherent in all things, abstract forms that give precise character to every distinct thing. But these Forms were not just related to physical being. These Forms also gave rise to such things as nations or city-states, families, professions. As an Athenian typically very interested in public life, he vigorously sought to know these Forms which undergirded the life of the good city or republic. He wanted to understand these Forms in order to design a better society – better than the one (Athens) which had ordered the death of his beloved teacher, Socrates. Aristotle (mid 300s BC) was a more "down to earth" (materialistic) thinker than his idealistic teacher Plato. He was much more focused on the question of how we come to understand the immediate world around us – and how we ought to interact with it. Thus he worked hard to develop categories and rules for orderly thinking in logic, ethics, science, politics. Further, with regard to the immediate world around him, he was an "empiricist," one who was more focused on the things that could be directly seen and studied through the human senses. He viewed the world around him as a material entity, a physical structure open to the human senses for observation and study, a physical structure whose basic character was, through the workings of the human mind, open to our understanding and even control. He had little use for Plato's Forms – that is, the divine order that supposedly stood above or behind physical reality. He preferred simply to study "reality" itself. He reserved his understanding of divinity for the starry realm above the earth. Democritus

Less well known to us today is Democritus (mid-late 400s: a contemporary of Socrates) of Abdera (Thrace). In his own day he was widely recognized as a brilliant thinker who brought to the ancient Greek world the atomic theory of the cosmos. Basically his view was that all life is merely the composite structure of invisibly minute particles of hard matter: atoms. These atoms (eternal in their being) are structured into the more visible material entities we observe in our world--through laws of motion (also eternal in their existence). Democritus was also a profound materialist in his view of human life. To him life is simply patterns of motion of these soul-less atoms – operating in accordance with equally soul-less laws. The human soul itself is simply a brief pattern in the working of the atoms--a pattern which forms in the human womb, developing and then breaking down over a human lifetime until it simply ceases to exist when we draw our last breath. To Democritus there was no such thing as eternal life. Likewise, God or Divinity was to him simply a construct of human thought – and had no real existence in the cosmos. In so many ways Democritus anticipated – by thousands of year – the direction science would take in its development within the modern West! |

|

|

Very early Greek origins

At some very distant point in time, dating anywhere between 1900 and 1500 BC, a number of different Aryan-speaking peoples moved westward from southwestern Russia and invaded/settled in wave after wave into the land we know as Greece. There they established fortified towns in the valleys between the many mountainous ridges that reach down to the sea and divide Greece into a number of distinct geographic units. Each town was headed by a chieftain or warlord (or ‘king’ as we later termed them). The Mycenaeans or Achaeans

The inhabitants, sometimes identified as "Mycenaeans" or sometimes as "Achaeans," were invaders of the land who spoke an early form of Greek and would become known to later Greeks as the military heros in Homer’s epic war story or poem, the Iliad. Later important Greek cities such as Athens and Thebes can trace their origins back to Mycenaean times. The region prospered moderately (in neolithic terms), especially after the collapse in the 1400s of the region’s dominant sea power, Minoan Crete (from which they had actually derived a great deal of cultural influence, including their early form of Greek writing). Later the Mycenaean Greeks presumably in the late 1200s or early 1100s BC extended their power further around the Aegean with their defeat of the rival power, Troy – though experts still debate the details or even the actuality of this event described centuries later (750 BC?) by the bard Homer in his great epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Dorians

But this Mycenaean/Achaean strength eventually began to decline, and after approximately 1150 BC Greek culture fell into a 400-year long Dark Age. This was either caused by, or led to, yet another wave of Greek invaders from the Northeast, the ‘Dorians.’ All archeological evidence seems to indicate that probably (though not certainly: debate lingers on) the Dorians disrupted life in Greece in a very major way. Certainly the Doric invasion set off a secondary wave of Greek migrations in around 1000 BC – principally to the shores of western Asia Minor. Ionians from Attica (around Athens) retreated across the Aegean to the central-western shores of Asia Minor (to Miletus) and gave their name ‘Ionia’ to this particular region along the Asia Minor coastline. Aeolians (perhaps a later group of Greeks to appear on the scene) settled the north-western shores of Asia Minor. Dorians themselves eventually continued their migration across the Aegean to the shores of southwestern Asia Minor and to Crete. In any case, the warlike Dorians eventually settled themselves into the Peloponnesian peninsula – where they ruled over the helots, the enslaved or enserfed Greeks who had originally lived in the area. Sparta grew up as a sort of country town at the heart of Doric culture. But interestingly, Athens (and its hinterland of Attica) managed to fend off the Dorians – and retained its older Achaean culture. Greece’s "Archaic Period" (700s - to the late 500s BC)

In the 700s BC Greece began to experience a commercial revival, growth of its population – and emergence of political powers in reviving Greek towns in the form of local aristocracies (rule by the heads of prominent families). But prosperity also strengthened the power of the more numerous commoner class, who found champions in the form of tyrants – who would use their political power to support the political cause of the Greek lower classes. Political revolutions of sorts thus shook the Greek world as new prosperity put power in the hands of all sorts of people. As a result democracy (rule by the common people or demos) – or something like it – resulted in a number of cities. This rise of the common classes however inspired Sparta, where a small elite of Spartan military citizens ruled over the vast numbers of people in surrounding towns and villages, to take an ever tougher stance of rulers over ruled – creating the famed (because of that toughness) Spartan military aristocracy. Extensive Greek colonization around the Mediterranean

With this economic revival of Greece there was also a large increase in the population – causing a serious strain on Greece’s available farmland to feed that population. However the surrounding seas, which the Greeks viewed not as a barrier but as a source of life (in fact a superhighway for them to move across), offered them an escape from their problems. Thus excess population was sent out to create new settlements or colonies – extensions of sorts of the sending cities. During the 700s and 600s BC they sailed east and west and discovered lands that they could colonize with their excess population (much as other cultures were doing at the time, notably the Phoenicians – located along the Syrian coast – with whom the Greeks had active commercial relations). From the city of Corinth colonies were established to the West on the island of Sicily and on the southern Italian peninsula (this would eventually come to be called Magna Graecia or "Greater Greece"). One of those colonies, Syracuse (founded in 733 BC), soon became a major city by its own right. Some of the Euboean towns (just north of Attica) sent settlers to the Syrian coast. From Miletus and other coastal towns in Asia Minor (a region known as Ionia) settlers were sent through the straits into the Black Sea and established Greek towns around the coast. Settlers crossed to the Egyptian and Libyan coasts of Africa. Others sailed west beyond Sicily and established towns along todat's French Mediterranean coast. By the 500s they were reaching to Spain and northern Italy. Thus in the course of the 600s BC "Greece" came to describe an area much larger than the land we today call Greece. In those ancient days "Greece" encompassed a whole huge area along the northern half of the Eastern and central Mediterranean Sea. And if we include the various Greek cities planted along the coast of the Western Mediterranean (such as Marseilles in southern France) we are describing a culture that was very extensive. Soon Greek towns along the Western coast of Turkey (Ionia) and Sicily and Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) would achieve tremendous cultural growth of their own – often surpassing in quality the level of culture of the sending cities back home. |

Greek colonization around

the Mediterranean

Wikipedia - "Ancient

Greece"

|

| We

now turn to the question of the thought processes that began to take

shape as Greek thought or philosophy. However, we need to be

cautious here as we depict the Greeks as thinking this or that.

Unlike their contemporaries, the Greeks were an independent-minded

lot. They had no strong priestly hierarchy to discipline the

people to a particular orthodoxy. So while some Greeks gave

further thought to life’s possible higher order – others continued

quite gladly to worship the Olympian gods of the heights or skies

(Zeus, Apollo, Athena) or the older pre-Olympian gods of the

earth/underworld (Pan, Dionysus, Demeter) with passion and even frenzy

suitable to the passion and frenzy of their gods. The Olympian Pantheon

Through tales we probably heard even in our childhood we are at least somewhat aware of the Greek pantheon, that is, the full community of Greek gods and goddesses whom the Greeks supposed to live atop Mount Olympus. This community was presided over by Zeus; his wife Hera played also an instrumental role in shaping events among the gods and goddesses. In fact the stories of life on Mount Olympus shifted over time, the gods took on new responsibilities, and changed in character and personality over the generations – so it is really difficult to give a definite explanation as to what role each of the many gods and goddesses played. Homer and the Higher Order

Homer was an ancient bard (late 800s or early 700s BC?) whose epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, gave tighter definition to this divine order. He portrayed a cosmos of rather fickle and often cruel gods who, from Mount Olympus, called the shots on earth. It was often a wild and crazy affair. Yet some small sense of equity or justice prevailed to force the gods to behave (somewhat). In Homer's saga, the Iliad, the gods have taken sides in the war between the Greeks and the Trojans. They serve as protectors over some of the key human players in the drama--most notably Hector and Achilles. But their powers are limited – not just by Zeus' dominion, but by forces which even Zeus cannot control. The Greek heros can be protected by the gods – but their ultimate fate, and the timing of such fate, not even the gods can set aside. Zeus can hold the scale by which the length of the life of the hero Achilles is measured – but Zeus himself cannot influence the outcome. "Fate" has a higher power than even the Olympian gods. Indeed, by the time of Homer (mid-700s BC?) ultimate Order is seen as somehow transcending the world of the humanlike Olympian gods. Such Order is a mystery – yet it is quite real. Also, we see in Homer's work a very strong moral as well a religious message. It seems that the sagas of Homer were designed to touch the hearts of the aristocratic, more military minded of the Greeks. Very likely this was some carryover from the religions brought into Greece by the Greek (Aryan) invaders – offering religious encouragement and moral justification for their dominant political roles. The moral theme underlying these sagas was (not surprisingly) that of valor – valor of the lone conquering hero in the face of overwhelming odds and even death. Hesiod and an Ordered Pantheon

In another very early Greek work (700BC?), the Theogony of Hesiod, we see the Greek mind beginning to formulate a strong sense of order – hierarchical order – with the realm of the gods. Hesiod carefully explained the original creation of the earth (sacred Gaia) and the heavens (home of the gods) out of the chaos of nothingness. He then explained the origin and historical development of the gods themselves, and finally the origins of man (and woman – as a bit of revenge on impudent man by Zeus!). Though he ascribed wide powers to the gods, it was clear that greater than they was the loftier process of creation itself. The Order of creation was a supreme force. We get also a sense of a more orderly world in Hesiod's Work and Days. This is "wisdom literature," very much like the wisdom literature of the other Mediterranean peoples which begins appearing about that same time among the Babylonians, Egyptians and Hebrews. This writing reads a bit like a farmer's almanac, advising on prudent agricultural practices and also includes (as you would expect of a Greek) much advice on practical seamanship. Underlying all of this is a sense of an autonomous Order that the common man can fairly well count on to make life more liveable (‘user-friendly’ we might say today!). Dionysianism

Side by side with the Olympian pantheon existed a number of religious ideas and practices of the Greeks. Some of it came in with the Doric invaders of the 1100s BC and some of it either predated all Aryan Greek invasions – or else came in later from the East. These tended not to be so orderly but instead seemed to anticipate the disorder of life caused by gods who needed to be appeased directly (through sacrifices) and often. Among the Greeks one of the most persistent and widely popular of such non-Olympian religions was Dionysianism. This was a rather wild fertility cult that perhaps predated the Greeks – a cult which managed to get a quite a hold on the Greeks at some point in their history. Being a fertility cult, it was a rite closely associated with the growing season – especially of the grape, the source of the Greek's precious wine. Drunkenness was thus a natural accompaniment to the festivities. It's hard to get a fix on the real character of Dionysianism – as it seems to have evolved quite extensively over the generations. It may have originally included blood sacrifice – perhaps even human as well as animal. Indeed part of the original Dionysian myth brings the hero Dionysus to a bizarre death at the hands of female devotees, who literally tore him limb from limb in a religious frenzy. It seems however that gradually this worship form was toned down by the Greeks – until it became a respectable worship form involving even the Greek aristocracy (who were always the bastions of original Olympian worship). Indeed, it was the refinement of Dionysianism that produced Greek drama – for it was at the Dionysian festivals that the famous Greek playwrights (Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, etc.) offered their new theatrical pieces to their Greek audiences. Orphism

Orphism seems to have been part of that effort to tame Dionysianism. But even this later development within Dionysianism is so clouded with mythology that it is hard to tell how or where it all started. The figure of Orpheus stands at the heart of this Dionysian "movement." There may have actually been a religious reformer who gave rise to the Orphic myth. But by and large, the Orpheus that has come down to us in story or myth seems to belong to the world of the gods rather than men. According to the story, Orpheus was born to either a Thracian king or god and a muse. The father gave him his instincts for adventure (he was part of Jason's Argonauts); his mother gave him his musical talents. But he too suffered destruction at the hands of frenzied female worshipers--and like Dionysus, traveled to the underworld and returned. Thus he too was part of the ancient fertility cycle. Orphism shared many features in common with another worship form found further to the East: Hinduism. Orphism developed a theology of reincarnation and transmigration of the souls through endless cycles of birth, growth, decay and death – in which escape from the grip of this eternal dance was the desired goal of the Orphic devotee (as with Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism). |

|

|

Western Philosophy Emerges at the ‘Edges’ of the Greek World:

Ionia and Magna Graecia When we think of "Greece" today we think of that hand-shaped peninsula projecting out from the Balkans of S.E. Europe into the Mediterranean Sea. We think of Athens, Thebes, Corinth, Sparta. This is the "heartland" of ancient Greece. But, as we have already seen, "Greece" actually reached from the Ionian shores of Asia Minor to Southern Italy and Sicily (called "Magna Graecia" by the Romans) ... and beyond even that – in both directions. In fact, it was these two further reaches – east (Ionia) and west (Magna Graecia) – that tended to be the more prosperous parts of the Greek world, at least until the 5th century BC. It was also these two further reaches that first gave birth to the philosophy that the Greeks so excelled at. Miletus, a prosperous port city in Ionia, was in fact where this speculative Greek mind-set first really took shape. There in Miletus began the first famous school of Greek philosophy, organized and led by Thales of Miletus. Thales of Miletus (ca. 624-546 BC)

Thales

(THAY-leez) is usually thought of as the "Father" of Western

philosophy. For reasons not known to us (until the time of Plato

in the late 400s BC we have no actual writings of the earliest Greek

philosophers, only bits and pieces about them told by others – others

not necessarily sympathetic observers!), Thales was not content with

the idea that things are the way they are because of the doings of the

gods. Thales

(THAY-leez) is usually thought of as the "Father" of Western

philosophy. For reasons not known to us (until the time of Plato

in the late 400s BC we have no actual writings of the earliest Greek

philosophers, only bits and pieces about them told by others – others

not necessarily sympathetic observers!), Thales was not content with

the idea that things are the way they are because of the doings of the

gods.Thales was well versed in the scientific learning of the East – and probably traveled to Egypt to study the mathematics, geometry and astronomy of the Egyptians. He put his learning to work as a military engineer – and was fabled for his scientific genius. He predicted a solar eclipse, measured the shadows of objects (from pyramids to ships) to estimate their distances or locations. It is reported of him that he even diverted a river in order to better position the Milesian army against an enemy city. But it is in the area of philosophical thought that Thales is best remembered. Thales was interested in discovering, through the process of rational enquiry, the essence or substance of all matter. He looked out on the world as a by-product of some material substance – a single substance which by its own makeup or inner mechanics could bring into being all other things. For him that single substance was water. Perhaps such a conclusion was inevitable for one who grew up near the sea and who undoubtedly often watched the power of the clouds above and the waves below during a tempest. But remember also that the ancient world widely shared the view that creation emerged from a watery void. In any case, it is important to understand how significant his probing into the essence of things was. He may not have got the right answers (though he was not really so far off in his view of water as the original substance) – but he was asking what modern science even today considers the right questions. Thus in ascribing the dynamics of the universe to water as the formative substance, rather than to the gods as the formative powers, he became our first known "materialist" or "secularist." Anaximander of Miletus (ca. 610-547 BC)

Thales' rational inquiry was taken up by Anaximander (ann-AKS-imander), reported by some to have been a student of Thales. In many ways he continued the intellectual tradition of Thales, becoming enlightened in a number of the sciences of the day. He is reported to have written down his vast learning on a wide range of subjects – though we have today only a small portion of his work, Concerning Nature. We know also however that Anaximander objected to Thales' theory – on the basis that water could not be the formative substance of life and yet at the same time one of its end products. Anaximander speculated that the original substance of the universe was some kind of primal, formless material which is found infinitely throughout creation – the material source of all created things (including water) and the material into which the universe will eventually return. He also speculated that the world was the result of a process of moving forces, a process that holds the universe steadily on its course – and leads it into the future. He saw this process as one ultimately of moving all things to maintain or restore a primal balance, one in which the multitude of forces in the cosmos work in the long run to counterbalance each in order to produce a basic harmony. Hot balances cold, dry balances wet, etc. to provide a cosmic harmony. But the actual dynamic of life involves a separation of these opposites – a falling into their particulars (an act of cosmic ‘injustice’), from which then a basic urge toward harmony (a return toward ‘justice’) moves them forward. This is the cause of motion or action in the universe: the urge to reharmonize. He speculated that the earth was a solid object hanging in a fixed position in the emptiness of space because it was equidistant from everything else, the very center of balance of all the forces in the universe. He might have viewed the world therefore as a ball or globe at the very center of the universe, but the flatness of the earth seemed so self evident that he supposed instead that the earth might be a huge cylinder, like a drum. We move around on one of the flat sides of the drum, held in place by balancing forces arising from the other flat side of the drum. He also looked at his universe in terms of its natural history: things as we know them today are a result of this process or urge of things to come into balance. This urge toward balance moves all things forward through time from one state or condition to the next, producing an ‘evolution’ of all things – from simpler into more complex forms. Human beings evolved rather more recently in the long natural history of the cosmos. Anaximander really was raising the ‘teleological’ issue in philosophy. He looked at creation, at life, from the point of view of where did things (material things) come from, why were they here, and what was their destiny. He too rejected the notion that this was all a matter of the doings of the gods on Olympus. And he too, like Thales, surmised that the vital forces of life are somehow contained within the ‘stuff’ of life itself. He, like Thales, was a materialist – and also an evolutionist! Anaximenes of Miletus (flourished mid-500s BC)

Anaximenes (anak-SI-muneez) was reportedly a pupil of Anaximander's and the third in the trio of great Milesian philosophers. He rejected most of Anaximander's theories about the world and the surrounding universe. He felt that it was self-evident that the world was a flat object, not a cylinder, and he rejected the idea of the earth just hanging in a void of space. Like Thales, Anaximenes looked to a less mysterious source of all things, to a primary material substance foundational to all things, one more readily present in our observable world. Anaximenes concluded that the primal substance of life was air or mist (pneuma) – an invisible substance that filled all the universe. It could be both the source of all things, and yet one of the created things itself – because of its power to change form. Here too, it was probably natural for Anaximenes to accord air the honor of being the primal substance or underlying material of all things. Greeks commonly understood air to be the ‘breath’ or ‘spirit’ (also pneuma) of life, the source of the soul, and so it was logical to think that air might be the primal substance of all things, the soul or spirit of all life. In any case, he argued that through a process of becoming more or less dense, air could change form. Thus fire was air in its most rarified form. The natural progress from there as air thickened was: wind, clouds, water, earth, and stone. Also, the soul quality of air (as the Greeks understood it) could explain movement, events, life itself. All in all, Anaximines' theory of the substance of life seems more complete than his Milesian predecessors. It was truly a great intellectual accomplishment – though being founded on a faulty premise, we find it interesting only for its methodology and not for its conclusions. Heraclitus (flourished ca. 500 BC)

An Ionian from Ephesus (not too far away from Miletus), Heraclitus (hera-CLY-tus) continued the quest for the material origins of life – yet holding all the while a rather mystical view of life. Heraclitus concluded that fire was the primordial element of an eternal, uncreated earth (it has always existed!). But he took up some of the logic of Anaximander in his view of the essence and the dynamics of things. To Heraclitus, all things come into existence by being separated from something else. Yet all is structurally one – at least potentially so. This structural unity he called the Logos. It is a higher order of being than the world of separate things. The Logos is the ultimate condition that beckons all things back to a state of unity. What we see in the world is perpetual flux. Things are ever changing. Nothing is permanent. They are constantly struggling to achieve a unity through the combination of their opposites. They are drawn forward by the Logos. Yet because things balance, the movement forward of one thing produces the retreat of its opposite. Thus things up are balanced by things down (like a hill), things light are balanced by things dark, things old are balanced by things young. This separation of things from the larger harmony of existence is rather unavoidable: thus strife and conflict are natural parts of life, a key part of life's dynamic. Without this separation, there would be no observable motion or action in life. It is this movement, this flux, that constantly changes things, thus causing fire to turn to water, day to turn to night, winter to turn to summer. This will always be – as it has always been since the beginning. Further, Heraclitus concluded that what we observe in the world is a dynamic of life rather than just a collection of things. Life is not made up of inert objects. For instance a flame is not a thing, but is a process which we are observing. Light and heat are not objects, but processes we are experiencing. Even living things are indeed not truly ‘things,’ but are a convergence of many forces which produce individual uniqueness – for a while. Even individual living objects are constantly changing phenomena, are entities in flux, separated from the Logos, urged forward in life by a desire to return to the Logos. |

|

|

The Mathematician and Mystic

We

treat Pythagoras apart from the other early Greek philosophers, since

his contributions were so unique, so unlike the philosophical tradition

that had been growing up in Ionia. We

treat Pythagoras apart from the other early Greek philosophers, since

his contributions were so unique, so unlike the philosophical tradition

that had been growing up in Ionia.Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos, just offshore from Miletus and so he would have been familiar with some of the philosophical doings on the Ionian mainland. But Pythagoras was a very original thinker and departed dramatically from the Ionian philosophers in his reflections on life and the universe. Perhaps this was because (as it seems) he traveled and studied extensively in the East, where he might have picked up his more mystical outlook on life. But in any case, he eventually left Samos (he disliked the politics of his homeland) and made the southern Italian (or Magna Graecia) port city of Croton his new home. There he founded a school – one which was to have a deep influence on Greek culture. Pythagoras is a hard figure to pin down. He was a mystic and his work really was intended for only the ‘initiates’ of his school. It was secret stuff! Further, his work was carried forward by his devotees – and probably much of their developmental thinking got mixed in with his to give us "Pythagorean" philosophy. Also, we can't tell whether he was strongly influenced by Orphism – or if Orphism was strongly influenced by him! For it was through Pythagoras that Orphism seems to have gained respectability among the more prominent Greeks – through whom then much of what we know about Orphism was transmitted on to us today. In any case, Pythagorism forms the polar opposite of the materialistic philosophy of the Ionian philosophers we just outlined above. While the Ionians were looking out into the world around them to find the primal substance or foundational material of life, Pythagoras was looking beyond – to causes higher than merely the surrounding world of material substance. Pythagoras was no materialist. He was no secularist. He was a transcendentalist; he was a mystic. He saw the grand order of the universe not in terms of physical substance or matter – but in the beautiful proportions and mathematical qualities that seemed to stand behind all physical matter. He saw the secrets of the universe not in what he observed "out there" but how what was out there struck him within. He was interested in probing the mind's understanding, interpretation, or reasoning in response to that physical world. Here within human consciousness was where true reality – higher reality – was encountered. Here is where, according to Pythagoras, we truly meet God. Here is where we in fact became God. To look for these hidden harmonies, these mathematical qualities inhering in life, these abstract formulations of the universe, was a divine enterprise. It linked us up with the eternal power of the heavens. Thus Pythagoras plunged into study of the world around him – and came up with some of the most astute observations about the structure of the universe. We remember him for discovering the formulas for computing the sides of a right triangle; we remember him for uncovering a number of basic rules that geometry rests on; we remember him for discovering the mathematical rules for the musical harmonies or scales; we remember him for arguing that the universe is a perfect sphere – as well as the sun, moon and earth. Obviously Pythagoras was not able to reduce all dynamics in life to mathematical formulations. But he certainly laid out the case that the universe could and should be studied on these terms. Western science would be impossible without this understanding. True – he was pursuing a mystical agenda in doing so. But so is science – though it pretends not to be doing so! It is hard to appreciate fully the impact of Pythagoras on Western thought. Mostly we look back to Plato and Aristotle as the heavy-weights of Western philosophy. But these two philosophers, coming over a century and a half later, were really only building on – or reacting to – the intellectual edifice which Pythagoras himself had laid out for Greek civilization. The West owes Pythagoras much – very much. |

|

|

Parmenides of Elea (fl. early 400s BC)

Parmenides (parr-MEN-ideez) was a major shaper of the Eleatic (Magna Graecia or Southern Italy) philosophy which contended (much like Anaximander and Heraclitus) that behind changing appearances stands a pure, unified, permanent or unchanging Reality which our thoughts and logic point to. Parmenides held that the actual observable world is merely a dim and broken reflection of this pure, holistic Reality. This Reality is always present with us: the past is a merely present memory only. The notion of determining some distant origin of life is itself absurd, because the material of life could not have come into being out of nowhere; indeed, Reality always is. Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BC)

Empedocles (em-PED-icleez) was a philosopher-scientist or naturalist living in Sicily. He posited the four-substance theory of life's fundamental structuring: earth, air, fire and water – shaped into various natural forms through the opposing forces of love and strife. He combined his naturalistic observations with somewhat mystical observations (perhaps under Pythagorean influence) to leave an impressive intellectual legacy within Magna Graecia. Anaxagoras (ca. 500-428 BC)

Anaxagoras (anak-SA-gorus) was another Ionian philosopher – except that he left his homeland and settled in Athens – marking the beginning of Athens as a (or the) center of Greek philosophy. According to Anaxagoras, the sun is a red-hot stone (not the god Helios), as are the distant stars. The moon merely reflects the sun's light. He offered a mechanistic explanation of most things (in anticipation of modern science) but reserved the view that the Eternal Mind (nous) is what activates living things. |

|

|

The political rise of Athens

During most of Greece’s Archaic Period the Spartans had been considered the dominant political power or hegemon in Greece. But during the 500s BC Athens, which was well positioned at the center of a huge Greek world, and possessing a number of natural advantages (a very strong citadel, a wide fertile region surrounding it, and closeness to the sea), soon rose to prominence. The Athenians were accomplished sailors; they also developed a very strong navy to protect Athens’ commercial interests overseas. And thus having the strongest navy of all the Greek city-states, Athens was early looked to in order to provide leadership in organizing the city-states into a great Greek navy, one designed to keep the Persians away from Greek shores. Also, though the extreme rigors of the Spartan military life have made the Spartans famous throughout history as exceptionally brave and accomplished soldiers, the Athenian military was in many ways the equal to the Spartan military, though the temperament of the two armies differed quite dramatically. Thus Greek leadership was divided between – and often competed for – by both Sparta and Athens (Corinth and Thebes were also powerful, though only at a secondary level). Athens’ struggle to secure democracy

But Athens was wracked by internal problems. Athens' rich and powerful aristocracy, long used to dominating Athens' political and economic life from its political council, the Areopagus, found itself increasingly challenged by the Athenian commoners (not really all that common, since they still occupied a much higher status than the more numerous xenoi or "foreigners"’ in Athens ... and the even more numerous slave portion of the Athenian population). The aristocrats first attempted to control Athens’ affairs with a very tough legal code or constitution (in which the penalty for a wide range of offenses was death) laid down by Draco (ca. 620 BC) – which, though an improvement over the older oral laws and traditions, still did not satisfy the political desires of the commoners. However his constitution did provide for the creation of a Council of Four Hundred, its members drawn from the commoners by lot.  A generation later, in the early 500s BC, another aristocrat, Solon,

serving as archon (one of several leaders governing Athens), was

commissioned to reform this constitution. He attempted to find a

compromise between the contending social classes by ranking the

citizens into four classes and giving each of them a certain number of

economic and political duties and rights. But soon after his

departure from power, class rivalries gradually returned.

Peisistratus, a nephew of Solon, seized power on behalf of the poorer

citizens, thus becoming "tyrant," or champion of the poor. His

political base was never secure and he was in power – and exiled –

frequently from 546 to 527 BC as political confusion continued to grip

Athens. A generation later, in the early 500s BC, another aristocrat, Solon,

serving as archon (one of several leaders governing Athens), was

commissioned to reform this constitution. He attempted to find a

compromise between the contending social classes by ranking the

citizens into four classes and giving each of them a certain number of

economic and political duties and rights. But soon after his

departure from power, class rivalries gradually returned.

Peisistratus, a nephew of Solon, seized power on behalf of the poorer

citizens, thus becoming "tyrant," or champion of the poor. His

political base was never secure and he was in power – and exiled –

frequently from 546 to 527 BC as political confusion continued to grip

Athens.Eventually a compromise was achieved (509 BC) – in no small part due to the need to achieve unity in the face of the political threat posed by both Sparta and Persia. A popular politician named Cleisthenes was elevated to power to reform the constitution. He reorganized the tribal basis of Athenian citizenship from four to ten tribes – membership based no longer on class but on residence in the city. From these tribes were drawn (by lot) members of the all important legislative and judicial councils. He saw this not so much as democracy as isonomia (full legal equality of all citizens). The Persian challenge

In the latter part of the 500s BC, just as some of the Greek towns (most important: Athens and Sparta) were beginning to grow in power as "city-states," the Persians surprised the world by conquering Mesopotamia, Syria, Asia Minor (including the Greek Ionian colonies there) and Egypt. This is the first time that nearly the whole of the Near East had been brought under a single rule. The Ionian rebellion. The Greeks living in Ionia did not particularly take well to this Persian domination and rose up in revolt against Persian rule in the 490s BC. The citizens of the Greek city-state of Athens were quick to back the Ionian rebels – who, however, were eventually forced back under Persian rule. This action of Athens and other Greeks in supporting the Greek Ionian rebellion drew the wrath of Persia and led to a Persian desire to crush any further Athenian or other Greek ‘meddling’ in Persian affairs. This then in turn forced the two leading Greek city-states, Sparta and Athens, into cooperation (in fact forcing a general Greek unity among all the Greek cities that had previously been lacking). Marathon and Thermophylae (490 BC) and Salamis (480-479 BC). Thus the Persian- Greek wars began – forcing Sparta and Athens into cooperation (in fact forcing a general Greek unity among all the Greek cities that had previously been lacking). In two major encounters about ten years apart (490 BC at Marathon and Thermophylae and in 480-479 BC at Salamis) the Greeks succeeded in defeating Persian armies and navy sent to Greece – thus not only securing Greek independence, but elevating Greece to a new status politically. The Delian League. By the mid-400s Athens was the dominant sea power in Greece, Sparta the dominant land power. But the sea was the more important element in Greek life at that time – and thus Athens naturally tended to dominate Greek affairs. In fact though the Persians had been twice defeated by the Greeks their shadow continued to loom over Greek thinking – and thus Greek defenses stood always at the ready, headed up primarily by Athens which had organized a number of Greek cities into a defense organization known as the Delian League. The Golden Age of "Periclean Athens"

The

fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important

in the future development of Greece. Spurred on by the continuing

threat of Persia, Greece developed its own strength, especially under

the leadership (even dominance) of Athens. Athens after these two

grand defeats of the Persians soon became the center of a newly rising

Greek civilization - with Athens itself reaching the height of its

power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political leader Pericles (490-429) The

fact that the Greeks had escaped Persian rule was to become important

in the future development of Greece. Spurred on by the continuing

threat of Persia, Greece developed its own strength, especially under

the leadership (even dominance) of Athens. Athens after these two

grand defeats of the Persians soon became the center of a newly rising

Greek civilization - with Athens itself reaching the height of its

power and glory about 450 BC, roughly the time of the political leader Pericles (490-429)Athens’ democracy and the leadership of the very capable general/statesman Pericles combined to offer Athens’ citizens a very rich life. A lavish building program turned the city into an architectural marvel. And the tendency of Greece’s finest minds to gravitate to Athens made it ‘the school of Greece.’ The rise of political realism in the writing of history

Breaking from the Homeric tradition of narrating glorified hero stories, the historian Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC) wrote of events as he had himself investigated them according to a more secular or 'rational' approach. In his Histories he details the Greco-Persian Wars of his times ... focusing on various battles and the Greeks and Pesians who directed those wars. A generation after Herodotus, Athenian general Thucydides (c. 460-400 BC) took the writing of Greek history even further down the empirical road with his History of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. He left out the intervention of the gods and narrated events as much as possible on the basis of actual political and military events and the personalities and strategies of the commanding officers of both sides.

Herodotus Thucydides

Greek playwrights develop deep psychological drama

The father of Greek drama (mostly his tragedies have been preserved) was Aeschylus (c. 525-456 BC), writiing his plays as part of the competition taking place during religious festivals for the God ... most usually Dionysus. Although he was from Eleusis and traveled widely (even to Sicily) his plays were widely popular in Athens. Another of the ancient Greek dramatists was Euripides (c. 480-406 BC), whose plays presented noble people with very ordinary – when not actually tragic – human circumstances, forced to make difficult and often very destructive decisions. But the most popular of the dramatists in Athens was Sophocles (c. 496-406 BC), winning the most competitions over a long, fifty-year period. He is also the best known today of the ancient Greek dramatists, with such works as Oedipus Rex and Antigone ... still studied and enacted today. He too wrote plays that looked deeply into the psyche of his characters – a dramatic realism acquired through his long service to Greece (he was personally involved in both the Persian and Peloponessian Wars).

Aeschylus

Euripides

Sophocles

|

|

| Internal problems with "democracy" Actually Athenian democracy was more an attitude than a political institution or policy. The commoners were jealous of their political rights and quick to defend them against any appearance of usurpation from any source. Tragically, this ‘democratic’ attitude was easily molded by the shapers of ‘popular opinion’ – by the political satire of the popular theaters of Athens ... and by the political maneuvering of clever speakers in the Athenian Assembly, in particular by the Sophists and their wealthy disciples – sort of the ancient version of modern day trial lawyers, who specialized in playing on the prejudices and fears of the people in order to whip up this or that popular mood ... which they skillfully directed according to their own personal ambitions. The Sophists. As the Athenians’ public life in the middle and second half of the 400s BC developed in its richness and importance, wealthy families hired tutors for their sons in order to prepare them for leadership roles in the public assemblies. This was where the laws would be pronounced on and applied. This was where economic, diplomatic and military decisions that were key to the well-being of the community would be made. They wanted their sons to become persuasive in their rhetoric, quick in public debate and noble in their public bearing – so that they would find themselves at the heart of the doings of these public assemblies. A particular class of wise ones or ‘sophists’ (sophia = ‘wisdom’) gladly offered their teaching services for a fee to these families. They built their learning or wisdom around the need to produce practical results in the form of skilled or adept students. As for the higher issues of life such as truth, goodness, justice, etc., in general the Sophists tended to be agnostic – that is, they professed to have no knowledge about (or even concern for) such ultimate or transcendent things. Indeed, they functioned as if such things did not really matter in the course of actual existence. Success was measured not in possessing the knowledge of ultimate truth, but in knowing how to use truths (or ‘truthiness’ as it is sometimes termed today) for personal political and economic gain. Protagoras (ca. 490-421 BC). Protagoras (pro-TA-gorus) was perhaps the foremost of the Sophists – and definer of its basic philosophy. According to him, the quest for absolute truth led only to contradictions. Indeed, to him all truth was relative anyway, only probabilistic in its existence. To Protagoras, ‘things’ existed for our understanding only through the words we gave them (abstractions). All religions and philosophies were merely social conventions useful to good order (the heart of the Sophists' philosophy). The absolute measure of the good in anything was only in its relative usefulness to someone. Knowledge was thus to be valued only in its ability to bring success to human effort – as in public affairs. Democratic cruelty. Sadly also, "ostracism" or exiling of Athenians by their fellow citizens became a very notable feature of Athenian society. At a special general assembly citizens were invited (by these Sophist-trained demagogues) to record the name of a person they might want exiled on a broken piece of pottery and deposited it in urns. These shards or ostraka were tallied by a public official. The person receiving the most votes (although at least a minimum of 6,000 votes) was automatically exiled for ten years.  The Athenian democracy’s abuse of the military hero Themistocles.

In 472 or 472 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor! [It

would take some time and distance from this sad episode before the

Athenians would recognize the cruelty they delivered the one man who

not only saved Athens from Persian destruction … but put the Greeks on

the path to greatness.] The Athenian democracy’s abuse of the military hero Themistocles.

In 472 or 472 BC the Athenian general Themistocles … who had been one

of the Athenian commanders at the Battle of Marathon, who then led the

Athenians to develop massive sea power and subsequently devised the

scheme to trap and destroy the Persian navy at Salamis, and who was the

leading political figure over the next ten years … was brought before

the ever-suspicious Athenian Assembly – fed by rumors coming from the

Spartans of a role in a political conspiracy (entirely false in fact,

designed cleverly by the Spartans to destroy their rival Themistocles)

– and adjudged by the Athenian commoners to be guilty of the crime of

arrogance. He was thus was ostracized. He fled to Macedonia

– then moved on to Ionia … where the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes offered

to bring him into Persian service as a regional governor! [It

would take some time and distance from this sad episode before the

Athenians would recognize the cruelty they delivered the one man who

not only saved Athens from Persian destruction … but put the Greeks on

the path to greatness.]The Athenian democracy’s abuse of Socrates. Also, very notably, the West’s most famous philosopher, Socrates, for instance, who was loudly critical of the amoral antics of the Sophists, would eventually (late 400s BC) become the object of the satire of the stage and demagoguery of the Assembly speakers. Both groups turned the public against him ... and forced his tragic death by a decision made by the Athenian Assembly. |

|

|

Athenian arrogance / imperialism

Another (and similar) major problem facing the Athenian democracy would be the arrogant attitude it came to assume with respect to its fellow Greek city-states – and the resentment this would breed among these other Greeks. At this point Athens no longer was led by wise men with a deep sense of high-minded virtue … but by cynical, manipulative, self-serving politicians … setting a similar moral tone for the entire Athenian community. With the passing of time, as the Persian threat seemed to dwindle – but Athenian collection of dues from its allies for ‘defense’ purposes continued nonetheless – resentment by members of the Delian League against Athens grew, especially when it became obvious that this money the other cities were sending to Athens had little to do with Greek defenses and more to do with a lavish Athenian building program going on during Athens’ days of glory. Consequently Athens' Greek allies felt as if they had been seduced into surrendering their independence to a growing Athenian Empire. Certainly also, the money they were sending Athens could have been used to improve their own cities. Anger against Athens began to grow among the other Greek city-states. Sparta, the major rival to Athenian power, with its well-disciplined land army, was quick to take advantage of this discontent and organized a rebellion against Athens in 431 BC. Also Thebes, seeing the growing mood of Greek rebellion against Athens, decided to make a bid for dominance in Greek affairs. The Peloponnesian Wars … and the political decline of Athens

Thus wars (the ‘Peloponnesian Wars’) broke out in Greece (431-421 BC; 421-404; 395-378 BC) that tended to ravage Greece – yet seemed to resolve nothing. The worst of these were the engagements between 431 and 404. Truces would be declared only to have one party or another decide that it was advantageous to break those treaties and start up a new round of wars. Also political leaders played treacherous games of shifting their loyalties according to their personal advantage. Pericles' efforts to keep Athenian spirits high. For a while the great general and Athenian political leader Pericles was able to keep Athenian spirits high as it struggled with the hostility of the surrounding Greek world. In his funeral oration (as recorded and probably edited by the historian Thucydides) – delivered in 431 in honor of the Athenian soldiers who had died in the first round of the wars – extolling the great political freedoms enjoyed by the Athenians, the sense of equality that bound them together, the rule of merit rather than birth that established the Athenians’ place in society, the openness of Athenian society to ideas of all kinds ... and the sense of unity and the willingness to take risks that led them to protect sacrificially their beloved city when faced with an enemy threat. All these things, Pericles stated, made Athens the "school of Greece" – the great society that it was. These were noble words. But Athens was soon to find itself unable to live up to these lofty ideals (if it ever did really).  Decline.

Things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long lasting siege of

Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens, taking

the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC). Athens’

new leader Alcibiades (Pericles’ nephew) proved to be largely a

disaster for Athens, as he led Athens on ruinous expeditions and

switched loyalties constantly ... including even siding with Athens’

enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC) and then Persia (412-411 BC) during

his cynical political career! Decline.

Things went quickly downhill for Athens. A long lasting siege of

Athens by Sparta created devastating conditions within Athens, taking

the lives of many Athenians, including Pericles (429 BC). Athens’

new leader Alcibiades (Pericles’ nephew) proved to be largely a

disaster for Athens, as he led Athens on ruinous expeditions and

switched loyalties constantly ... including even siding with Athens’

enemies, first Sparta (415-412 BC) and then Persia (412-411 BC) during

his cynical political career!Ruin. The war gradually led not only Athens but also much of the rest of Greece to ruin. Finally in 405 BC the Spartans (now allied with the Persians) defeated Athens even at sea – and Athens was forced into a humiliating surrender (she was forced to tear down her town walls, surrender her fleet and give up all her overseas possessions). Only Sparta’s compassion prevented Corinth and Thebes from getting their wish to level all of Athens and enslave the entire Athenian population. Nonetheless from this point on, Athens’ day as a great power was over. But eventually Sparta’s domination proved to be as unwelcome in the rest of Greece as the Athenian domination had been – and the civil war was renewed. Thebes and what was left of Athens joined with other Greek cities to finally bring Sparta to defeat in 371 BC. |

|

It

was during these troubled times that Greece's most outstanding

philosopher, Socrates, undertook to teach the Athenians about ultimate

truth ... and how to live life accordingly. It

was during these troubled times that Greece's most outstanding

philosopher, Socrates, undertook to teach the Athenians about ultimate

truth ... and how to live life accordingly.Socrates is known largely through Plato's heroized representation of him. Plato's many writings are presented as accounts of Socrates in dialogue with his pupils. But it is difficult at times to tell what portions of these dialogues were truly of Socrates, and what part were Plato's own thoughts – put forth through the mouth of Plato's venerable teacher. Certainly we can tell even from Plato's characterization of him that Socrates turned the course of philosophical enquiry around – from its earlier focus on natural science, to a focus on ethics or public morality. Socrates was keenly interested in such subjects as justice, beauty, goodness. But he could also turn his mind to physics and metaphysics when the occasion arose. According to Socrates, objective reality and what our minds understand of reality are separated by a great mental divide (the general consensus of Greek philosophy by that time). But rational inquiry, meticulously yet humbly pursued (his dialectical method), could close this divide. In using rational methods of inquiry, human mind and soul could be brought to discover transcendent (thus absolute) truth and goodness – and personal happiness. Socrates felt optimistic that knowing the truly good would necessarily direct a person to act in line with this knowledge. Also, the quest for such knowledge was the very heart of life itself – its highest form (almost a divine enterprise). Socrates' troubles with "democratic" Athens

Unfortunately, the Athenians proved not to be so enlightened by the truth as Socrates had hoped. The Sophists were a particularly grand annoyance to Socrates. Their depiction of truth as being a substance mostly of mere convenience particularly flabbergasted Socrates – who saw truth as lofty and absolute. Socrates didn't fare so well before the "enlightenment" of Greek democracy either. In the end his teachings that dignified human knowledge seemed highly blasphemous to the pious commoners of Athens and the Athenian Assembly voted for Socrates’ death. His crime was "teaching the youth not to reverence the gods" (not true at all) ... and his punishment was given somewhat honorably in that he was to inflict this death penalty on himself (poison, usually) ... although the Athenians expected Socrates to do what most Athenians did when the Assembly turned against them: flee Athens. This was certainly the counsel of Socrates’ devoted disciples. But Socrates reasoned that to flee would be to discredit the very truths and moral principles to which he had dedicated his life in his teachings. Thus he took the poisonous hemlock and died, surrounded by his disciples. The principle of democracy becomes highly questionable to wiser minds

Because of the ease by which Athens’ popular democracy was so easily manipulated to serve the interests of the demagogic Sophists, 'democracy' and all its stood for came to be intensely disliked as a governing principle by many (the Athenian philosopher Plato for instance) ... or at least not highly regarded (his student Aristotle for instance). Indeed, in no small part due to the attitudes of these two famous philosophers, a certain distaste for 'democracy' indeed was held by most all political philosophers down into modern times. Even the framers of the American constitution were unwilling to accord the new nation a full democracy, but instituted instead a ‘mixed’ system, one of checks and balances designed to permit, yet restrict, popular participation in the nation’s politics – out of a fear of democratic instincts getting out of control. It would be until only the beginning of the 20th century (notably with President Wilson, who saw democracy as the cure-all for the world’s ills) that democracy would come to have the glamor and intense devotion that it does today. |

|

Democritus

(de-MOCK-ritus) was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Greek natural

philosophers of those days. But he refused to grace Athens with

his presence, choosing instead to remain in his native Thrace where he

had grown up and studied under Leucippus. Here he was closer to

the older philosophical environment of the Ionian materialists – of

whom he was undoubtedly the greatest of all. Remaining in Thrace

did in no way diminish his reputation, for even in his own time he was

considered the equal to the Athenian philosophers in intellectual

stature and clarity of thought. Democritus

(de-MOCK-ritus) was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Greek natural

philosophers of those days. But he refused to grace Athens with

his presence, choosing instead to remain in his native Thrace where he

had grown up and studied under Leucippus. Here he was closer to

the older philosophical environment of the Ionian materialists – of

whom he was undoubtedly the greatest of all. Remaining in Thrace

did in no way diminish his reputation, for even in his own time he was

considered the equal to the Athenian philosophers in intellectual

stature and clarity of thought. Unfortunately we have none of his own works today. But he was reported so widely by others that we have a fairly clear understanding of his incredible thinking. We know that he came from a very respected (and wealthy) family from Abdera in Thrace. Democritus was well traveled (certainly to Egypt and possibly Babylon) and well educated in astronomy and mathematics. His great importance lies in his development of Leucippus' atomist theory of the cosmos. According to Democritus, the world is comprised of invisibly minute, solid, unchanging and eternal atomic (atomon: ‘indivisible’) particles suspended in a airy void. Those two things, the atoms and the void, is all that truly ‘exists.’ All else, particularly the things that we are able to actually see – visible matter – is merely a result of various combinations of atoms as they move mechanically through the void. Atoms do not come into being or go out of being. They are eternal in existence. What changes, what comes into life and what eventually wears down and dies, producing the vibrant or ‘lively’ qualities that we recognize as the nature of all living things, is simply the way these atoms are constantly attracted or drawn together and rearranged to produce the action or ‘motion’ we observe about such life. Also eternal are the principles undergirding such motion or such rearrangement of these atoms. That is, the quality of motion itself is also eternal. Thus the basic ‘stuff’ of reality is eternal: atoms and their motion. What changes is the resultant visible structures that we observe about life. Such a materialist vision of life necessarily raised the question of the origins and character of human consciousness – of the existence of the soul (nous). Democritus' answer was that the human soul too is made up of atoms, special atoms of a certain variety that are particularly lively and easily airborne – entering the body in our breathing. Human death occurs – as we well know – when a person draws his last breath. Thus to Democritus, breath or pneuma was that special conveyance of life that gave a person a living spirit. (the Greek for air, breath and spirit are all pneuma). At death all of that breaks down, disintegrates. The vital qualities of a human life simply cease when no more breathe is drawn into the body. There is no eternal nous that lives on after death. Nor was there in the theories of Democritus the existence of an eternal Nous that was Divine, that constituted anything we might call God. His theories required no such ingredient for them to function properly. What undergirded the working of his hypothesis about life, about the cosmos, was simply the eternal laws of nature which directed the atoms in their movement from one structure or arrangement to the next. In short, his theory was entirely mechanistic. He was also an embryologist, carefully studying the growth and behavior of biological life. He was also an evolutionist – in that he saw human form and life developing anciently out of the structure of water and mud – like worms! (the ancient presumption about worms was that they grew out of the ground the way a plant does, drawing on the earth to supply it with the building blocks of stalks, leaves, flowers, fruit.) |

|

Because

of the self-destructive arrogance of the Athenian Assembly … and

because of how easily the Athenian Assembly had been manipulated by

suspicious commoners and the unscrupulous Sophists to order the

ostracism of Thucydides and the death of Socrates, Socrates’ pupil

Plato (flourished early to mid-300s BC) came to have little use for

democracy itself, dedicating himself to formulating in his writings –

notably his famous work, Republic – instead a society dominated by a

wise and moral philosopher-king. Because

of the self-destructive arrogance of the Athenian Assembly … and

because of how easily the Athenian Assembly had been manipulated by

suspicious commoners and the unscrupulous Sophists to order the

ostracism of Thucydides and the death of Socrates, Socrates’ pupil

Plato (flourished early to mid-300s BC) came to have little use for

democracy itself, dedicating himself to formulating in his writings –

notably his famous work, Republic – instead a society dominated by a

wise and moral philosopher-king.He obviously had in mind someone like himself ... an attitude taken up by many philosophers and intellectuals – and even ‘enlightened’ monarchs – down through Western history. That list would include even some recent U.S. Presidents! But Plato was no cynic ... and instead simply devoted himself all the more to the search for the Truth ... one that lies well above mere human interest and its self-serving rationalization. The quest for Truth

Meanwhile, Plato took up his teacher Socrates' cause ... and carried the matter of the study of Truth further – much further. At the heart of the tremendous intellectual contribution that Plato made to Western thought was his theory about the ‘Forms’ or ‘Ideas’ (Ideon) ... impacting Western intellectuals for countless generations – including even down to today. To Plato's way of thinking, the ‘reality’ that we see directly around us is merely a shadowy reflection of a ‘higher reality’ – one found well beyond our day-to-day world. This contrast between earthly reality and ultimate or ideal reality was a very important matter to Plato – and to all those who have been influenced by his thought ever since. The world around us that our senses perceive directly is an ever-changing, coming and going array of ‘particular’ things: the tree in our front yard, our neighbor next door, the brown cow just now eating clover in the field just outside the village, the beds and chairs in our house, the meal we are just about to sit down to, the yellow-orange sunset this evening, the song that we heard the tenor singing outside our window this morning, etc. These earthly things, these ‘particulars,’ have the sad quality of changing, aging, breaking down. The beauty of the flower, the sound of the beautiful song, the house we have just built, the strength of the athlete, etc. do not last very long in their splendor. And there is nothing on earth that is permanent, lasting or eternal. Not even the mountains – for they eventually wear down, even though the process may be slow and impossible to see directly. The Ideon

Being thus ever-changing or ‘impermanent,’ these ‘particulars’ are not truly ‘Real.’ And what is ‘Real’? Nothing on earth. But there is a realm of such Reality – which exists beyond our earthly domain – in the realm of the gods, in the realm of heaven. This is the unseen world of the Ideon (‘Forms’ or ‘Ideas’). In this lofty ‘world beyond’ exist a multitude of God-created Forms or Ideas or ‘Universals’ – such as Good, Truth, Beauty. They exist in perfection, just like the idea of a perfect circle, or the perfect relationship between radius of a circle and its circumference, in pure mathematical-like precision. They are Real, very real, the most real of all reality. They have transcendent and universal existence – like gods! Using the language of later Judaism and Christianity (which was heavily inspired by Platonist thought) this reality of the universal Forms or Ideas has its perfect existence only in the realm of God. This body of universals is what forms the very ‘Word’ (Greek: Logos) of God. The things on earth are made after the image of such divine perfection – though themselves never perfectly or consistently so. Earthly things, though inspired to take on the shape or character of these universal Forms or Ideas, fall far short of the perfect glory or perfect reality of these transcendent Forms/Ideas. The Parable of the Cave

In his work The Republic, Plato tells a story to illustrate his point about the flawed world we see around us and the purer, loftier realm of the Ideon. Suppose a person was born in a cave which had an opening high up that let light into the cave, but was so high that this person was unable to get out. All that person was ever to know was the reality of the cave. Now suppose that people outside walked in front of the cave from time to time, casting their shadows on the back side of the cave. The person inside of the cave could not see these people. But he could see their shadows. It is natural that he would believe that these shadows were the reality of ‘people’ – when in fact they were only shadowy forms of true people. So it is with us mortals in this world we so briefly inhabit. We believe that the world around us that our senses perceive is the real world – when in fact it is merely a shadowy reflection of a higher world our senses are unable to perceive directly. Discerning the Ideon

How could Plato be so certain that such Forms or Ideas truly existed? For one thing, our minds can certainly contemplate what the perfect might be – though we have never actually seen it. Our minds can contemplate perfect beauty or perfect goodness – just as we can contemplate the perfect circle. Surely, the ability to contemplate such things points to the fact that they indeed exist – or our minds could not conceive of them. But Plato did also offer up some ‘empirical’ (factual) evidence. Look at the movement of the heavens through day and night and season after season. There in the heavens perfection not found on earth certainly can be found. This seemed very compelling evidence (to Plato and the early thinkers) in testimony to the existence of the perfect in the heavenly realm. For Plato, the challenge facing us is to bring ourselves to the knowledge of such perfection. This was the highest calling of a human – to meditate on such perfection. Being occupied in such contemplation was the mark of true nobility in a person. Plato indeed felt that such noble thinkers (philosophers such as himself) should even be given the role of leading or governing the rest of society! For Plato, the task of contemplating such perfection lay half-way between mystical thought and rational or mathematical thought (as it had been for most Greek philosophers, especially since the time of Pythagoras). The mind of God, the realm of the Forms or Ideas was not totally passive in this relationship – offering up to the inquirer the gift of inspiration or insight. Without such a gracious gift from the realm of God, no person could ever hope to attain heaven's insights. Yet we mortals were expected to put our thoughts on such matters: for in this state of readiness the truths of God would yield themselves up. But the process seemed to be as much an internal focusing as an external focusing. In other words, we didn't look for heaven ‘out there’ as much as we looked for its evidence within our own thoughts, in the make-up of our own ‘souls.’ Plato had a sense of ‘fallenness’ about the human: that we had the potential for perfect knowledge of the divine realm – but had lost it both over time and in the process of being born into this shadowy world. The recovery of this knowledge (knowledge of the divine Forms/Ideas) amounted to being joined to the mind of God, the immortal and eternal essence of the Forms or Ideas. Thus the task of the teacher was to help restore us to this original knowledge: to draw it out from us – rather than push it into us as if knowledge were something that existed out there apart from us. Knowledge, ‘pre-existed’ within the soul and was led forth to realization by being touched by the mind. The mind, the memory, was fully loaded with divine knowledge – even of previous existences! Moreover, to Plato, death – which strikes terror in the human heart – was not an evil outcome of our all-too-brief human existences. Rather, he saw it as a process which separated the soul from the body: mind from matter, the heavenly from the earthly. Death had the effect of opening the person to perfect knowledge – knowledge which had been unavailable to our bodily senses while we were ‘alive’ on earth. Thus death offered us the advantage of finally becoming true being – living in true light. The soul, which had existed somewhere before birth of the individual, now lived on in eternity, free and fully developed. In sum, Plato placed little stock in ‘empiricism:’ the study through direct observation of the ways of the physical world around us. With the important exception of the study of the heavens, he felt that such study of the world ‘out there’ was unlikely to reveal Truth – and in fact would likely only serve to deceive us by giving us the false impression that the shadowy world around us was indeed ultimate truth. To Plato this was a horrible thought – fit only for peasants and the very ignorant. Rather, Plato was interested in uncovering this perfect world of the Forms – in bringing it to light to human understanding. Indeed, this was to Plato (and he many ‘Platonists’ who came after him) a religious enterprise – not just a matter of detached scholarship. Platonism, especially Middle-Platonism (about the time of Christ 300 years later) and Neo-Platonism (two hundred years after that), were to leave a powerful mark on the Western world-view. In fact, Christianity found that Platonist thinking aided considerably in making the Gospel of Jesus Christ more readily understandable to the larger Greco-Roman culture beyond its immediate Palestinian-Jewish birthplace. |

|

Aristotle

founded a new school of his own, the Lyceum. Aristotle went in a

direction opposite that of his teacher, Plato. While Plato focused his

attentions on the mysterious world of the perfect Forms, Aristotle

focused his attentions on the messier visible world immediately around

him. Aristotle was greatly fascinated by this empirical or physical

world. He was looking for Plato's Ideon or Forms contained within this

visible world. Aristotle

founded a new school of his own, the Lyceum. Aristotle went in a

direction opposite that of his teacher, Plato. While Plato focused his

attentions on the mysterious world of the perfect Forms, Aristotle

focused his attentions on the messier visible world immediately around

him. Aristotle was greatly fascinated by this empirical or physical

world. He was looking for Plato's Ideon or Forms contained within this