|

|

A general overview of the Hellenistic

Age A general overview of the Hellenistic

Age

Alexander Alexander

Alexander's conquest of the East Alexander's conquest of the East The Antigonad Dynasty The Antigonad Dynasty Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic Egypt The Seleucid Empire The Seleucid Empire The development of Hellenistic

culture The development of Hellenistic

culture |

|

|

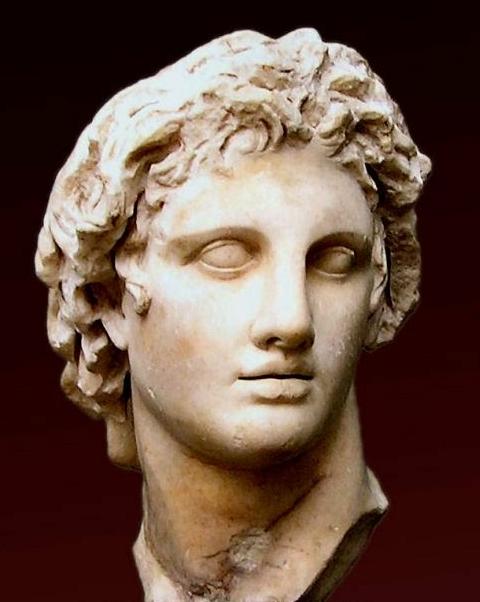

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)

The brief, meteoric rise (and sudden loss) of the young conqueror of the Greek North--Alexander of Macedonia--marks a critical turning point in the evolution of Greek or Western cosmology. Everything that seemed to lead up to the life of this conqueror of the known civilized world of his times and everything that proceeded onward from this amazing life threw the comfortable Greek cosmology into confusion, disorder. The Decline of the Greek City-State

The century prior to Alexander's arrival on the scene had been a time of gradual decline from the self-understood grandeur of Greece (during the "Age of Pericles" around 450 BC). True, the material culture of Greece even reached new heights during this period. But the moral-ethical foundations of Greek's cherished public life had been undergoing quite noticeable decay. From the time that the Athenian citizenry pronounced the death sentence upon Socrates (399 BC), philosophers had begun to wonder about whether things were indeed so orderly in Greece. Indeed, reaching back even to the beginning of the "Troubled Times" of the wars of the city-states in Greece (starting in 459 BC), Athens had been growing increasingly imperious in its relations with its neighboring city-states. Power, wealth, status seemed only to corrupt the Good Greek order. Cynics, Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics

Around the time of Alexander (around 330 BC) a series of new schools of political thought were founded by philosophers from around the Greek realm (especially around its eastern borders). Though each of these new schools was unique they all shared in common a view that the private life was the only place that a person could trust things to go right. They thus all drew back from the older Greek view that the highest good for a person was in the contributions they might make to the public life. These new philosophers instead looked within the human soul in their search for order, good, truth, beauty. They all tended to invite people to build a safe haven of life by withdrawal from the public domain and a focus on personal intellectual development. Here was where the blissful order could be found. But some, like the Skeptics, were not even sure that this was entirely a reliable haven. A sense of prevailing chaos seemed to be getting a grip on the Greek mind. Opening Up to the East

Alexander's conquest of the grand and vast Persian Empire to the East in Asia began what some might feel ironically as the spiritual conquest instead of the European West by the Asian East! Perhaps this is a bit of an exaggeration. Yet certainly intimate contact with the East through the new Greek Selucid (Syria and Palestine) and Ptolemaic (Egypt) monarchies opened Greek culture to strong Eastern influences--ones that reached to the heart of Greece, even to the venerable Athens. Here a mystical vision of the divine order--perhaps not too much different from Pythagoras' vision (whom we suspect had also been profoundly influenced by Eastern thinking through his travels there)--moved deeply into Greek thinking. Concepts such as life after death (or--a return to life of an eternal soul as a new person), notions such as the most noble life being found in a mystical union with the very essence of God, these were ideas that began to take hold in Greek thinking. On-going Platonism and the new Stoicism stepped right into this thought mode. So would elements of Judaism and, eventually, much of Christianity. |

|

|

A reprise: The Peloponnesian Wars

Athens, having the strongest navy of all the Greek city-states, was early looked to in order to provide leadership in organizing the city-states into a great navy, one designed to keep the Persians away from Greek shores. But slowly Athens began to use its position to leverage its allies into a state of financial and political dependency, even using moneys intended for the joint navy instead to build public projects in Athens. Sparta, the major rival to Athenian power, with its well-disciplined land army, attempted to champion the cause of those city-states that wanted out from under Athenian dominion. Thebes also briefly made a bid for dominance in Greek affairs. Thus wars broke out in Greece (459-446 BC; 431-421 BC; 421-404; 395-378 BC) that tended to ravage Greece--yet seemed to resolve nothing. Truces would be declared only to have one party or another decide that it was advantageous to break those treaties and start up a new round of wars. Also political leaders played treacherous games of shifting their loyalties according to their personal advantage. One of the more notable examples was Alicbiades, who rose to leadership in Athens after Pericles--then switched sides to the Spartans when he was removed from his leadership position in Athens after having lost an important battle (in part due to some political intrigue against him at home)--only to be recalled later to Athens as leader again! So things went. The emotional fall-out

Slowly the sense of political morale began to sink among the Greeks. Disillusionment with the once-glorious city-state now grew profound among many of the Greeks. In a search for a solution to this problem Socrates had dreamed of a realm of justice; Plato had searched for the formula for an ideal Republic where the virtues of public life might be restored. But hope for a better public system began to wane. As the Greek wars continued, and there seemed to be no way to rise above Greek divisiveness, a sense of cynicism began to set in. Thus philosophers such as Diogenes began to recommend that Greeks find happiness within themselves--apart from the public domain. Soon that idea would be taken up by other Greek philosophers. Philip of Macedonia

While

the city-states of Classical Greece seemed to be enjoying tremendous

prominence (when not fighting each other), a new power was growing to

the North of Greece: the semi-Greek kingdom, Macedonia, under its ruler

Philip II (382-336). Many of the Greeks, including some

influential Athenians, looked to Philip to rescue Greece from its

military and political follies. But others, most notably the

Athenian statesman and orator Demosthenes, saw in the ascendancy of

Philip the end to Greek political values and liberties. While

the city-states of Classical Greece seemed to be enjoying tremendous

prominence (when not fighting each other), a new power was growing to

the North of Greece: the semi-Greek kingdom, Macedonia, under its ruler

Philip II (382-336). Many of the Greeks, including some

influential Athenians, looked to Philip to rescue Greece from its

military and political follies. But others, most notably the

Athenian statesman and orator Demosthenes, saw in the ascendancy of

Philip the end to Greek political values and liberties. Given the considerable Greek indecision about Philip – and given Philip’s military and political talents – it proved not that difficult for Philip to take control in Greece, step by step, conquest by conquest. In 338 he moved boldly and deeply into Greece and defeated at Chaeronea an alliance of Thebes and Athens sent out to stop him. He then called an all-Greek Congress, to which many Greek representatives came, to build Greek unity around his personal rule. But many, such as Demosthenes in Athens, argued fervently against accepting his ascendancy. In 337 BC he created the League of Corinth, which effectively put Philip at the head of all Greece (except Sparta, which Philip – and his son Alexander – left largely independent, through greatly constricted by surrounding Macedonian power). The age of the Greek city state was over. But so was the tenure of Philip. The following year, 336, he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards as part of a still not fully understood palace plot. Young Alexander

No

one was giving much thought to Philip's son, a young man of only

20. But Alexander surprised everyone by quickly revealing himself

to be every bit the man (even more so) than his father. He had

been carefully raised in Greek ways, studied under Aristotle (when not

off somewhere fighting battles!) – and had a mind to outdo his father

in achievements. No

one was giving much thought to Philip's son, a young man of only

20. But Alexander surprised everyone by quickly revealing himself

to be every bit the man (even more so) than his father. He had

been carefully raised in Greek ways, studied under Aristotle (when not

off somewhere fighting battles!) – and had a mind to outdo his father

in achievements. Coming immediately to power in 336 BC, he quickly put down challenges to his kingship in Macedonia and in Greece. He then moved to galvanize his rule by turning the combined Macedonian-Greek state he ruled toward the idea of ending the Persian threat to Greece forever. He intended to invade Persia – and not just wait as they had in the past for the Persians to take the initiative in their strained relations. He divided his Macedonian army (leaving some behind to keep his power secure in Greece) and added a large number of Greek soldiers to his ranks and then crossed into Asia Minor to raise the flag of anti-Persian rebellion by the various subject peoples living there under Persian tutelage. When he and his army set off toward Asia Minor in 334 BC no one had any idea of how far Alexander's ambitions in Asia were going to take them. |

|

|

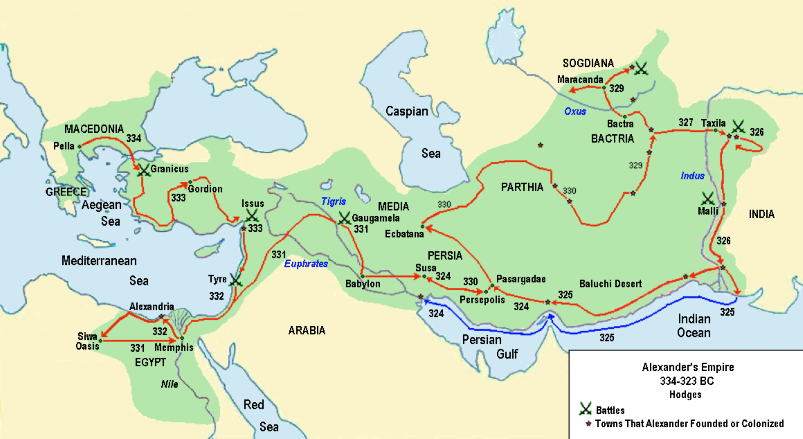

Granicus (334 BC).

Persian royal power had been in decline for a while, corruption within the bureaucracy was growing rapidly and the subject peoples were quite restless. Alexander saw his incredible opportunity as liberator or deliverer of these subject peoples. To meet this challenge from Alexander, Darius (III) sent his army out to crush this upstart Greek, only to have Alexander crush the Persian army instead at the Battle of Granicus (334 BC). The Persians retreated in dismay – and Alexander used the next months to consolidate his position as the new master of Asia Minor. Issus (333 BC) and Syria/Palestine

The next year the Persian army came out to meet him again – only to be defeated again by Alexander at the battle of Issus. This opened up the eastern end of the Mediterranean to Greek expansion. Indeed, Alexander then easily entered Syria and Palestine as liberator/conqueror, facing serious resistance only from Tyre and Gaza, both of which he destroyed. Most other cities opened their gates to the conqueror without resistance – and were met with fair treatment. Egypt

Then at this point he strangely turned away from chasing the humiliated Persian Emperor and pushed on around the Mediterranean shores to enter Egypt. Here too he was received without resistance ... in fact being received even as liberator rather than as an enemy. What might seem to be a mere side incident in the story is actually a very major piece in Alexander's life. No doubt out of a desire to get to the bottom of a story (and perhaps in part also out of a desire to impress his troops) that Philip was not his true father – that Alexander was actually descended on his father's side from one of the gods – Alexander journeyed to the Siwa Oasis in the Libyan desert to inquire of the famed priests of Ammon there as to the truth to the story. They confirmed that indeed the story was true. Indeed, Egyptian priests greeted him as a divine instrument of their god Ammon and crowned him Pharaoh. While in Egypt, he planted a Greek colony at the edge of the Nile delta – a fabulous Greek-Egyptian city bearing (as did so many of the towns or cities he founded) his name, Alexandria. It would soon grow to outclass all other cities around the Mediterranean ... and hold that position for centuries. Even with the rise of Rome, Alexandria retained the reputation for being the most sophisticated city in the Western world. It would be the center of fabulous Greek scholarship for at least another thousand years. Gaugemela/Arbela (331 BC)

But soon it was time for Alexander to turn his attentions back to the Persians. The Persians had been assembling the largest multi-ethnic army ever seen before in western Asia. But Alexander's army was more disciplined, more maneuverable and more personally loyal to its leader than the Persian army. Two prior defeats of the Persians also contributed to the high morale of the Greeks and the nervousness of the Persians. In 331 BC the Greeks and the Persians met in a mighty clash at the Battle of Gaugamela (or Arbela). Once again the Greeks were victorious, and once again the Persians and their king Darius were routed. Darius was eventually hunted down (330 BC) – and put to death for his cowardice by his own men as Alexander approached. Victorious in battle, Alexander now focused his attentions on consolidating his rule over his newly acquired territories. Interesting, and convenient for Alexander, even in the very heart of the Persian empire Alexander was greeted as a liberator/conqueror. Babylon and even Susa, the old Persian capital, greeted him as a liberator, and indeed Alexander did what he could in service as ‘protector’ of these grand cities. He wanted to rule over a land of wealth, not ruin. The sack of Persepolis

However the new Persian capital of Persepolis proved to be a different matter. The city tried to take a military stand in its own defense – and chose the unwise tactics of parading before Alexander's army 800 badly mutilated Greeks who had been captured earlier, presumably as a ploy to demoralize the Greeks. Instead it merely infuriated them (and Alexander) – and the Greek troops went wild, slaughtering its inhabitants and burning Persepolis to the ground. Consolidating his conquests by creating an East-West synthesis  Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler. Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler.Onward to Central Asia and India

Alexander would not let up on his conquering ways, particularly as he began to learn of other lands that lay to the north and east beyond the Persian empire. He pressed on with his Macedonian-Greek army, first into central Asia (328 BC), where he faced bitter conditions and bitter resistance and where there was very little of value (Roxana excepted!) to add to his already vast dominions. He then turned eastward (327 BC), again passing through bitter situations in Afghanistan in an attempt to reach India with its rumored wealth and splendor. Crossing the Hindu Kush he descended into the Indus River valley (326 BC) where at the Jamnia River he defeated King Porus and his army – though turning them into allies after all. Hearing of the wealth of India further East along the Ganges River he decided to press on with his conquests, only to be faced with firm resistance from his troops. They would go no further East. In fact, after nine years of conquest, they were ready to return home to Greece and Macedonia. For the first time ever, Alexander and his ambitions faced defeat. Against the resistance of his own troops, he could do nothing. The Journey Back to Babylon

So he now turned his army south along the Indus River, facing stiff resistance from the Indian towns and armies all along the way, becoming seriously wounded himself as he personally led an effort to scale the walls of a resisting town (Malli). He escaped with his life only because of the sacrifice of his troops in their wild effort to protect him from further harm. Even then he was so badly wounded that he required several months of convalescence before he was able to continue the movement of his troops south to the Indian Ocean. Finally reaching this destination (325 BC), he divided his army – with half returning to Persia by ship and the other half, led by Alexander himself, moving overland toward Persia. But the second group had to cross a totally inhospitable stretch of desert, which through heat and thirst left ten thousand of his soldiers dead along the way and Alexander physically and mentally exhausted in his arrival back in Persia. His Last Days

On arriving at Babylon he cleaned out much of the corruption that had set in on his administration during his absence. He then returned to the program of integrating his Greek and Persian supporters – including organizing (in 324 BC) a massive marriage ceremony between his Greek soldiers and Persian women, taking two Persian princesses as additional wives of his own (a very non-Greek concept). He then had rebellions to face down, including one among his own Greek troops (also 324 BC).His last enterprise (323 BC) was to have been a massive exploration of the water link between Babylon and Egypt by 1000 ships he had built for the occasion. But his body was spending itself out – not only because of his constant exertions, but because of his deep drinking and carousing that went on for hours. Just prior to his departure on this grand sailing expedition he caught a fever which his tired body could not shake – and as he lay dying ten days later his army passed silently before him to bid their hero farewell. He died the next day, June 13, 323 BC. |

The palace at Pella in Macedonia

... where it all began

Miles Hodges

Miles Hodges

Alexander attacking Darius

III in the the Battle of Issus - mosaic

First century BC in Pompeii

in the House of the Faun.

Perhaps after an earlier

3rd century BC Greek painting of Philoxenus of Eretria.

Archeological Museum of

Naples

Alexander attacking Darius

during the Battle of Issus - detail

|

The Division of Alexander’s Empire

A power struggle for control of his empire quickly ensued. Alexander's son was a mere baby. Perdiccas quickly moved to make himself regent – eliminating scores of his rivals. A number of Alexander’s generals were named as governors or satraps. But Perdiccas was killed by his own troops and Alexander’s empire fell into a civil war among his generals. Intrigue and murder among the contenders for power became widespread. In 309 BC Alexander’s now 13 year old son and his mother Roxana were murdered. The generals now had a free hand in grabbing the Empire. From Alexander's newly established city in the Nile Delta, Alexandria, Ptolemy took control of Egypt. From his capital at Antioch in Syria Seleucus took over what he could of the Asian portion of Alexander's conquests (Seleucid Asia got quickly pared down to Syria and Palestine and the upper reaches of the Tigris River). Cassander was awarded Macedon, Lysimachus Thrace - though eventually Antigonus established a hold over Greece and Macedonia. The Indian portion of the Empire was turned over to the Indian general Chandragupta Maurya – and ceased being part of the Greek or Hellenistic world. |

The Alexandrian Empire a century later

|

Antipater and Cassander. Antipater had been appointed to govern Macedonia in Philip's absence while off at war as early as 342 BC and was the major player to force the Athenians to accept Macedonian domination as a result of the Macedonian victory in the 338 Battle of Chaeronea. Antipater then continued to govern the region when Alexander came to power. He also was acknowledged by Perdiccas as ongoing governor of Macedonia. However he had to let go of the region of Thrace in order to face and defeat a rebellious Sparta … but soon thereafter became ill and died (319 BC). Eventually his son Cassander – an early friend of Alexander and fellow student of Aristotle – would take over his father's responsibilities in Macedonia/Greece … but would turn against the Alexandrian political legacy. He was ruthless and in order to secure his power he had Alexander's wife Roxana and their 13-year-old son Alexander poisoned. Furthermore, his efforts to establish a dynasty of his own in Macedonia-Greece failed to take hold as a murderous family feud largely destroyed the family and brought Cassander's political legacy to an end. Antigonid Macedonia-Greece

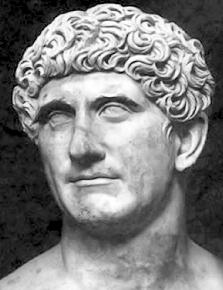

Antigonus I Monopthalmus. Perdiccas had tried to remove Macedonian General Antigonus I Monopthalmus ('One-eyed') from his recently assigned command of part of Asia Minor ... and Antigonus had escaped to Macedonia, then commanded by Antipater. But with Antipater's death – and the fighting which followed that – Antigonus gradually rose to dominance throughout most of the Alexandrian Empire in Asia. Eventually Seleucus was able to defeat Antigonus (the Babylonian War of 311-309 BC) and secure the huge Eastern portion of the empire for himself. The peace treaty following the war left Asia Minor and Syria to Antigonus ... but was soon challenged by Cassander of Macedonia and Ptolemy of Egypt.  Demetrius.

Antigonus's son Demetrius was able to defeat Cassander in 306 BC ...

and Antigonus followed up this victory by declaring himself and his son

as kings, indicating a move of independence outside of the Alexandrian

Empire. Soon other Alexandrian leaders did the same (c. 305 BC),

with Cassander, Seleucus, Ptrolemy and Lysimachus also taking titles as

kings of their own lands. Demetrius.

Antigonus's son Demetrius was able to defeat Cassander in 306 BC ...

and Antigonus followed up this victory by declaring himself and his son

as kings, indicating a move of independence outside of the Alexandrian

Empire. Soon other Alexandrian leaders did the same (c. 305 BC),

with Cassander, Seleucus, Ptrolemy and Lysimachus also taking titles as

kings of their own lands.With Antigonus and his son Demetrius still possessing the strongest military and navy among the contenders, the others leagued together to oppose Antigonus ... and in 301 BC the 80-year-old Antigonus was killed in a battle with Seleucus and Lysimachus. Demetrius was temporarily set back by this same battle ... but took advantage of the jealousy among the victors ... and was able in 294 BC to take Athens by blockade and sieze the throne of Macedonia from Alexander, Cassander's son. He then began to build a massive navy ... with the obvious intent of conquering his many opponents – who naturally formed an alliance against him. In 288 BC Ptolemy's fleet arrived at Greece ... sparking a revolt among the Macedonians – who disliked Demetrius intensely (his reputation for licentuousness and extravagance had profoundly alienated the Macedonians). When also in 287 BC Pyrrhus and Lysimachus appeared with their armies, Demetrius' troops themselves deserted him and joined the enemy. Then Athens revolted against his rule. Now Demetrius was unable to crush a widening rebellion as famine and disease nearly destroyed his army. Then the left that task to his son Antigonus, and headed East to take on Lysimachus ... who was joined by Seleucus. At this point his troops abandoned him and he was captured and imprisoned (285 BC) ... dying there two years later (283 BC).  Antigonus II Gonatas.

Now his son, Antigonus II Gonatas, took over the throne of

Macedonia. He had already proven himself earlier in helping

to contain a rebellion among the Greek Thebans ... which his father,

with his famous siege engines, was finally able to bring to full defeat

(291 BC). Then when his father headed off to battles in the East

in 287 BC, Antigonus was able to drive off Ptolemy's fleet and force

the surrender of Athens. Antigonus II Gonatas.

Now his son, Antigonus II Gonatas, took over the throne of

Macedonia. He had already proven himself earlier in helping

to contain a rebellion among the Greek Thebans ... which his father,

with his famous siege engines, was finally able to bring to full defeat

(291 BC). Then when his father headed off to battles in the East

in 287 BC, Antigonus was able to drive off Ptolemy's fleet and force

the surrender of Athens.But with his father's death, Antigonus went into something of a political wilderness. He stayed out of the Diodochi battles among principally Lysimachus, Seleucus and Ptolemy ... with Macednian King Lysimachus being killed by Seleucus in 282 BC, then Seleucus murdered by a son of Ptolemy in 281 BC ... who then rellinquished his claim to the Egyptian throne and took the title of King of Macedon. But his rule would be short, for in 279 Ptolemy was captured and killed fighting Gauls who were invading Macedonia from the North. This brought Antigonus back into action ...defeating the Gauls in 277 BC ... and allowing him to take the position of King of Macedon – then later King over the rest of Greece. But Antigonus now faced a new threat ... from Pyrrhus, who in 275 BC, had decided to return to Greece from Italy, after having attempted to conquer the rising Romans there ... usually successful in battle – but at a huge cost in numbers to his own army (thus the term 'Pyrrhic Victory'!). He had run out of money to pay his mercenary (mostly Gallic) troops ... and decided to pluder Macedonia for gold. Pyrrhus was unquestionably the most famous Greek fighter of his day – and when Antigonus went out to stop Pyrrhus' attacks, Antigonus found himself surrounded ... and his troops (and officers) changing sides ... taking Antigonus' elephants with them. Antigonus managed to escape. Pyrrhus then went deeper into Greece, trying (unsuccessfully) to take Sparta, then failing that, turning to Argos ... to meet Antigonus – who had gathered another army. Pyrrhus managed to get inside Argos but the narrow streets kept his troops and elephants from effective action. The action turned to disaster, and Pyrrhus was killed in the process. At this point Antigonus was effectively back in control of Macedonia and Greece. But the challenges to his rule would not be over. In 267 BC, Sparta and Athens united in an attempt (with the help of the Egyptian King Ptolemy II) to throw off Macedonian rule ... and recover their former greatness. But finally in 263 (or 262) BC Sparta and Athens – despite the support of Egypt – gave up the struggle. The problems with Ptolemaic Egypt nonethless continued and, with Antigonus's alliance with the Seleucids, the Ptolemies lost much of their territory in Syria, Southern Anatolia (modern Turkey), and Ionia ... and were forced in 255 BC to recognize Antigonus' rule in Greece. Then also a young Greek nobleman, Aratus, attempted to stir an uprising against Antigonus on behalf of the freedom of the Greek cities. It took some considerable effort to bring Greece back under Antigonus' control. And so it went ... until 239 when at age 80 Antinonus died, leaving his kingdom to his son, Demetrius. Demetrius II. Demetrius II ruled only ten years (239-229 BC), with much the same kind of endless struggle with the Greek alliances (the Aeotlian and Achaean Leagues) occupying his reign. But it was ultimately a battle with invading northern tribesmen, the Dardanians, which brought his life to an end. Antigonus III. Demetrius's son Philip V was too young to take over at Demetrius's death ... so a regency was established in 229 BC with Demetrius's cousin Antigonus III. Antigonus succeeded in stopping the Dardanians and was able to keep good order within his realm (including breaking a Spartan rebellion) ... largely by working diplomatically with the Achaean League. But he died (of natural causes) in 221 BC following a victorious battle with a new group of invaders from the north, the Illyians. Rome enters the picture

Philip V.

In 221 BC, the 17 year old Philip finally took the Antigonid throne ...

and soon proved his worth in forming a new Hellenic League which in

putting down rebellious city states (such as Sparta) gave him full

respect in both Macedonia and Greece. But mounting problems with

Rome would occupy him greatly. At one point he entered into a

treaty with Carthaginian General Hannibal (then ransacking the Italian

countryside) ... only to have the Romans enter into an alliance the

Aetolian League (various Greek city-states generally opposed to

Macedonian rule). But with the Romans deeply occupied with their

2nd Punic War with Carthage, Philip was able to finally crush the

Aetolian League in 205 BC. But in 200 BC the Romans took up the

cause of some of the still-rebellious Greek cities and attacked

Philip's Macedon bringing Philip and his army to defeat.1 Philip V.

In 221 BC, the 17 year old Philip finally took the Antigonid throne ...

and soon proved his worth in forming a new Hellenic League which in

putting down rebellious city states (such as Sparta) gave him full

respect in both Macedonia and Greece. But mounting problems with

Rome would occupy him greatly. At one point he entered into a

treaty with Carthaginian General Hannibal (then ransacking the Italian

countryside) ... only to have the Romans enter into an alliance the

Aetolian League (various Greek city-states generally opposed to

Macedonian rule). But with the Romans deeply occupied with their

2nd Punic War with Carthage, Philip was able to finally crush the

Aetolian League in 205 BC. But in 200 BC the Romans took up the

cause of some of the still-rebellious Greek cities and attacked

Philip's Macedon bringing Philip and his army to defeat.1The Romans allowed Philip to keep his throne, but put him under Roman dependency ... and forced him to pay an annual indemnity of a thousand talents annually. But Philip proved to be cooperative with the Romans in their war with the Seleucid King Antiochus III and eventually the indemnity was lifted and Philip was allowed to rebuild his weakened rule. Finally, trouble developed when Philip's younger son Demetrius linked up with the Romans in an effort to take succession from his older brother, Perseus. Philip finally was led to execute Demetrius ... which broke the father's health. Philip died the next year.  Perseus (179-166 BC) would

be the last Antigonid king. At first Perseus conducted fairly

friendly relations with the domineering Romans. But the Romans

finally decided that he was a bit too independent and went to war with

him (Third Macedonian War, 171 168 BC) ... in which Perseus was

defeated and captured at the Battle of Pydna, was paraded in Rome in

chains and was imprisoned by the Romans. Additionally, some

300,000 Greeks were deported and enslaved by the Romans ... and their

land given to Roman settlers. This would finally bring an end to

the rule of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia-Greece. Perseus (179-166 BC) would

be the last Antigonid king. At first Perseus conducted fairly

friendly relations with the domineering Romans. But the Romans

finally decided that he was a bit too independent and went to war with

him (Third Macedonian War, 171 168 BC) ... in which Perseus was

defeated and captured at the Battle of Pydna, was paraded in Rome in

chains and was imprisoned by the Romans. Additionally, some

300,000 Greeks were deported and enslaved by the Romans ... and their

land given to Roman settlers. This would finally bring an end to

the rule of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia-Greece.Final efforts of Macedonia and Greece

to break free from Roman domination Then in 149 BC, Andriscus, an Anatolian clothmaker claiming to be a son of Perseus, organized a Thracian army with the purpose of liberating Macedonia from the Romans. At first he was successful and went on to form an alliance with the Carthaginians ... although the following year (148 BC) he and his army were defeated. Two years later (146 BC) Rome declared Macedonia to be a Roman province. This then prompted the Greeks – spurred on by foolish demagogues of the Greek cities of the Achaean League (another group of Greek city-states) – to rise up in revolt ... which turned out to be suicidal for the Greeks. As a result, the city of Corinth was laid waste (similar to what happened to Carthage that same year). Following this, there were no further thoughts among the Macedonians or Greeks about the possibilities of independence from Rome. They were now permanently part of the Roman Empire. 1The Roman legion proved itself to be a military formation superior to the traditional Greek phalanx (more easily maneuvered in battle). |

|

| Ptolemy I Soter (323-283 BC).

The most powerful of the Alexandrian kingdoms was Ptolemaic

Egypt. As Alexandrian regent, Perdiccas appointed General Ptolemy

(eventually nicknamed "Soter" ... in Greek meaning "Savior") as satrap

of Egypt ... then grew resentful as Ptolemy consolidated his power

operating from Egypt. Thus Perdiccas attempted to overthrow

Ptolemy, failing miserably in the effort and bringing on his death at

the hands of his own men. Ptolemy was wise to then turn down the offer to head up the entire Alexandrian Empire ... which would have brought him only unceasing problems. Instead, he further consolidated his position in Egypt (as well as outlying areas along and across the Mediterranean Sea. Then in 305 BC he took the title of Pharoah, helping to legitimatize his position among the Egyptians themselves. He hereby established the beginning of a dynasty that would rule Egypt for the next three centuries. He also began the process of turning the Ptolemaic capital city Alexandria into not only an economic and political power center ... but also the most noble of all Hellenistic cities in terms of its intellectual achievement (founding the great Royal Library of Alexandria) ... one that even the eventual conquest of Egypt by the Romans would not diminish.  Ptolemy II Philadelphia (283-246 BC).

Ptolemy's position was immediately taken in 283 by his son, Ptolemy II,

who had been co regent with his father the previous two years. He

developed his Egyptian navy ... and used it to counter the attempt by

Antiochus to bring the southern region of Syria (Judea) under Seleucid

rule. He also held off an attempt by invading Celts or Gauls to

try to establish themselves in Egypt (they did take control of part of

Asia Minor ... known subsequently as Galatia). Ptolemy II Philadelphia (283-246 BC).

Ptolemy's position was immediately taken in 283 by his son, Ptolemy II,

who had been co regent with his father the previous two years. He

developed his Egyptian navy ... and used it to counter the attempt by

Antiochus to bring the southern region of Syria (Judea) under Seleucid

rule. He also held off an attempt by invading Celts or Gauls to

try to establish themselves in Egypt (they did take control of part of

Asia Minor ... known subsequently as Galatia).He also continued the policy of his father to support the intellectual development of the capital Alexandria ... expanding the Library and supporting scientific research. It was during his rule that Greek culture would establish itself as the dominant culture of Egypt. The Septuagint Bible. And most importantly for Western Civilization, he was instrumental in having the Hebrew Bible translated into Greek as the Septuagint Bible.2 This brought this key piece of Jewish law and literature out of its narrower Hebrew cultural world into the much broader Hellenistic world, offering that almost "universal" Greek speaking world of the day easy access to what would eventually become the start up section of Western civilization's most foundational writing. More Ptolemies … and Cleopatras! Following Ptolemy II's death there were a succession of Ptolemies (for a total of thirteen!). They increasingly took on Egyptian ways ... especially in marrying their sisters (frequently of the name Cleopatra) such as the ancient Egyptian pharaohs had done. Indeed, one of these Cleopatras (II) would rule from c. 175 BC to her death in 116 BC through a series of husband brothers (Ptolemy VI: 180-145 BC; Ptolemy VIII: 144-132 BC) and then by herself (132-127) and again with Ptolemy VIII and her daughter Cleopatra III (131-127 BC). It was all very incestuous ... and all very Egyptian.   Ptolemy VI "Philometor" ("loves his mother") And as a general rule among the Alexandrians, these Ptolemies found themselves usually at war with the Seleucids of Syria as well as the Macedonians of old Greece. And of course these dynastic quarrels and the political confusion they generated began to weaken seriously the Ptolemaic dynasty ... so much so that the Romans simply moved themselves gradually into the position of protectors of Ptolemaic Egypt (just as they had done initially with Macedonia) … after 80 BC when an Alexandrian mob lynched Ptolemy XI (who ruled only a few weeks) after he murdered his stepmother – who was also his cousin and probably half sister.  The next Ptolemy (Ptolemy XII, popularly known as "Auletes"

or "Flute player") was actually more of a Roman client than a true

Egyptian ruler. At one point he was driven from power (58 BC) and

exiled to Rome by his daughter Bernice IV ... but restored to his

throne in 55 BC by the Romans (after Ptolemy made a payment of 10,000

talents to one of Roman Consul Pompey's Generals). But at this

point Auletes enjoyed his power only through the support of Rome. The next Ptolemy (Ptolemy XII, popularly known as "Auletes"

or "Flute player") was actually more of a Roman client than a true

Egyptian ruler. At one point he was driven from power (58 BC) and

exiled to Rome by his daughter Bernice IV ... but restored to his

throne in 55 BC by the Romans (after Ptolemy made a payment of 10,000

talents to one of Roman Consul Pompey's Generals). But at this

point Auletes enjoyed his power only through the support of Rome. Cleopatra VII and Mark Anthony.

When he died of illness in 51 BC, he was followed on the throne by

another daughter, the 18 year old Cleopatra VII – who had served with

him as co regent during the last year of his life – as well as her

brother and husband Ptolemy XIII ... but the latter only briefly.

After a failed attempt to win Julius Caesar's support by murdering

Pompey, who had fled to Egypt to escape Caesar, Ptolemy XIII was

defeated (with the help of Caesar, who was her lover!) and died in 47

BC in a civil war he waged against her. Cleopatra then chose another

younger brother (and husband) Ptolemy XIV to rule with her. Cleopatra VII and Mark Anthony.

When he died of illness in 51 BC, he was followed on the throne by

another daughter, the 18 year old Cleopatra VII – who had served with

him as co regent during the last year of his life – as well as her

brother and husband Ptolemy XIII ... but the latter only briefly.

After a failed attempt to win Julius Caesar's support by murdering

Pompey, who had fled to Egypt to escape Caesar, Ptolemy XIII was

defeated (with the help of Caesar, who was her lover!) and died in 47

BC in a civil war he waged against her. Cleopatra then chose another

younger brother (and husband) Ptolemy XIV to rule with her.When Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, she attempted to have her son, Caesarion (born from the affair with Caesar) to take his place in Rome. But Caesar's grandnephew Octavian took that position instead. Nonetheless, she had her brother Ptolemy XIV murdered (also 44 BC) and then elevated her son Caesarion to co rulership with her in Egypt. Following the assassination of Caesar, Rome itself fell into a series of civil wars among a number of Roman contenders for power. During this period the Eastern half of the Roman Empire (including Egypt) came under the command of the Roman politician and general Mark Antony (ca. 42 BC) ... with the Western half under his ally Octavian Caesar.  This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.Both Mark Antony and Cleopatra presumably chose suicide rather than face the humiliation at the hands of Octavian. Cleopatra's 17 year old son Caesarion was executed soon after. The Ptolemaic line of pharaohs had come to end. Egypt was now formally a Roman province under the rule of a Roman governor (30 BC). 2"Septuagint" from the idea of "Seventy" ... the number of Jewish scholars commissioned by Ptolemy II to come up with a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scripture or Bible. These 70 scholars worked independently of each other. In the 70-day period in which they did their work, they presumably came up with exactly the same Greek translation – word for word – something considered miraculous then ... and today! |

Ring with engraved portrait

of Ptolemy VI Philometor (3rd–2nd century BC)

Paris, Louvre Museum

The Nile mosaic of Palestrina,

showing Ptolemaic Egypt (c. 100 BC)

Paris, Louvre Museum

Cleopatra VII as an Egyptian

goddess

A brilliant woman who

charmed the Romans ... but got deeply involved in the political rivalry

between Marc

Antony and Octavian Caesar ... and lost both her country and her life

St. Petersburg, Hermitage

Museum

|

|

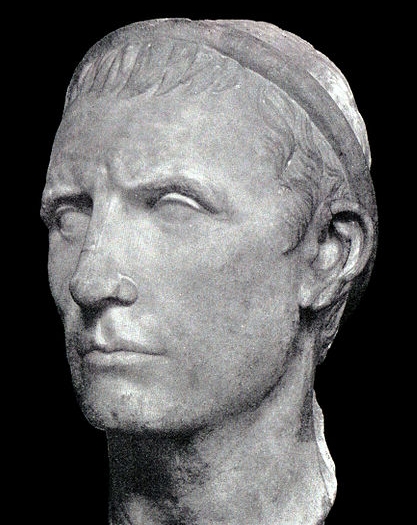

Seleucus I Nicator receives approximately the equivalent

of the former Persian Empire (312-281 BC)

But much territory still remained to the new Seleucid dynasty that he established. And into this land the Greeks migrated in large numbers, bringing their language and culture ... leaving a permanent mark on Central and West Asia that would only be replaced very slowly by a return of the pre Greek cultures (but much changed through Greek influence. Difficulties holding the Seleucid Empire together

Indeed, Greek Bactrian King Demetrius I Aniketos ("the Invincible") would invade India in 180 BC and set up a Bactrian Greek-Indian kingdom that would last over a century and a half. The Rise of Arsacid Parthia (247 BC). And Parthia (northeastern Iran) also moved to independence under the Greek satrap Andragoras (also around 250 BC) … but was not able to maintain its independence. An Asian (of Scythian origin?) named Arsaces soon overthrew him and laid the foundations in Parthia for the Arsacid Dynasty … which would eventually come to dominate all of Persia for five centuries as the powerful "Parthian Empire" (247 BC – 224 AD).  Antiochus III (223-187 BC)

Coming to the Seleucid throne at age eighteen, Antiochus was able over

his long rule to achieve key military victories that halted the decay

of the Seleucid Empire and brought most of lost territory in the East

and West back under Seleucid control. In the West he was able to

regain Syria and Palestine (lost earlier to the Greek Ptolemies of

Egypt), he extended Seleucid control eastward by recapturing Bactria

and Sogdiana … reaching even to the Indus River in West India

(Pakistan) and then heading south along the Arabian side of the Persian

Gulf. Antiochus III (223-187 BC)

Coming to the Seleucid throne at age eighteen, Antiochus was able over

his long rule to achieve key military victories that halted the decay

of the Seleucid Empire and brought most of lost territory in the East

and West back under Seleucid control. In the West he was able to

regain Syria and Palestine (lost earlier to the Greek Ptolemies of

Egypt), he extended Seleucid control eastward by recapturing Bactria

and Sogdiana … reaching even to the Indus River in West India

(Pakistan) and then heading south along the Arabian side of the Persian

Gulf.The Romans

But there were bigger problems in the West than his old Hellenistic rival, the Ptolemies of Egypt: Rome. By the beginning of the 100s BC the Romans were involving themselves in the chaotic diplomacy and military maneuvering conducted among the Greek states of northern Anatolia, the Aegean Coast of Asia Minor, and Thrace on the European mainland (the lower Balkan Peninsula). Cooperating with the Carthaginian General Hannibal – whose army was thrashing the Romans in their own homeland – Antiochus decided to ‘liberate’ mainland’ Greece from Roman influence. That was a mistake. In four years of fighting between Antiochus’ Seleucid army and the Roman legions, Antiochus was slowly ground down by the Romans, in 188 BC had to accept humiliating terms for peace, and watched the eastern provinces he had worked so hard to return to Seleucid control once again go on their independent way. Significantly among that latter group were the Parthians under the Arsacid dynasty … who moved boldly to take control of much of old Persia. Rome

now pretty much dictated matters ... at least within the Western

reaches of the Seleucid Empire (while the Eastern portions became

increasingly rebellious and independent). Seleucid kings came and went

in rapid succession ... and containing (or causing) civil strife

occupied most of their time in power. The death of the Seleucid Empire

By

the beginning of the 1st century BC little more than Damascus and the

area of Syria immediately around it was about all that the Seleucids

truly governed ... although they remained deeply involved in the

dynastic politics of the Eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea.

Far greater in power and importance by that time was the Greco Persian

(semi-Seleucid) kingdom of Pontus, to the north of Seleucid Syria ...

and encompassing all of Asia Minor and Anatolia (modern Turkey).

Finally,

Roman General Pompey took on Mithridates in battle in 66 BC ...

defeating him soundly and sending him into flight. Then in 63 AD,

with Pompey closing in on` him – and not wanting him and his family to

be subjected to a triumphal parade in Rome, Mithridates chose

suicide. Meanwhile (69 BC) the Romans had resurrected a small portion of the Seleucid Kingdom for its own political ends ... but after Pompey defeated Mithridates he redesigned the lands of Eastern Mediterranean into Roman client states, converting Seleucid Syria into a Roman province under the rule of a Roman governor.

3It is said that in a battle in 305 BC between the Greek and the Indian generals, Chandragupta was able to field 600,000 troops and 9,000 elephants. |

|

|

The dominating role of the Greek language

These new Greek states were in themselves huge political holdings – rated as independent kingdoms and even empires: the Antigonid Empire (Macedonia and Greece), the Attalid Kingdom (Thrace), the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom. They were viable political entities offering security and prosperity to their people. They were also unified by a new sense of Greek cultural hegemony. Though local peoples might cling to their more ancient tribal or regional ways, the Greek language and culture quickly established themselves throughout the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean (and the hinterland) as the medium of literature, philosophy and science. Thus Alexander did more than any actual Greek in establishing the Greek language as the dominant international tongue used by scholars, scientists, tradesmen, governing officials, not only in Alexander’s day but for centuries to come. Even when Rome extended its military power into the Eastern Mediterranean it did not supplant Greek with its own Latin. Indeed the Roman government itself took up the use of Greek in administering its Eastern holdings. The original works of Christian Scripture were not in Hebrew (which anyway had passed out of daily use in Jesus’ times) or even Aramaic (a local Semitic language used in Syria/Palestine) ... but in Greek, considered the only language adequate to cross the lines separating the various cultural groups making up the Middle East. Even Paul’s letter to Rome was written in Greek, not Latin. Eventually a translation had to be made from the Greek into Latin (the Latin ‘Vulgate’ translated by the monk Jerome in the late 300s, long after Christianity had been formally accepted as the official religion of the Roman Empire) - which the Western Church then went on to adopt as its official translation of the original Greek. A shift to a new sense of order in life

But this great Greek achievement came at a time of continuing confusion among the Greeks as to what the ideals of life ought to be. Certainly Alexander's imperial political legacy made trivial any residual Greek affections for the city-state - though certainly such sentiments were slow to die. The domain of politics now rested in the hands of lofty rulers - ones who even took on the Eastern affectation of being "gods." The noble Greek citizen directing the course of his cherished city was now an anomaly, even a dangerous one at that. But even beyond these changes in political style and vision lay other major changes in Greek life. Just as politics seemed to slip out of the hands of the Greek commoner and move to the loftier realm of royal, almost god-like authority, so even the sense of the source of life seemed to move away in the same direction. Life now seemed shaped by forces that greatly transcended direct human management. To achieve any sort of sense of connectedness with such transcendant sources, a person now had to look well beyond the realm of the surrounding physical or material reality - to the mystical realm of the Divine. True, the Greeks held on to their gods, personal protectors whom they hoped would protect them and intercede on their behalf with the higher forces of the universe. But ultimately they knew that it was with these higher forces that all things in the end drew their power, their direction, their life. Such a realm was not necessarily hostile. It was not necessarily chaotic. Indeed, a new Order seemed to be the rule of the day. But it was distant, beyond the easy understanding of the common man, mysterious in its nature and action. To reach such a realm required enormous amounts of concentration of human thought and understanding. Perhaps only those who had the luxury of free time could ever achieve such a connection, such a relationship with the ultimate. Philosophy thus began to take on a more complex character. It could no longer be found just in simple dialogues between a teacher and a citizen-student as in Socrates' days. It now required profound devotion to study, a deep focusing of oneself on the task, meditation, prayer even, to reach the goal of understanding. Philosophy was now a mystical, spiritual enterprise - engaged in by specialists. In short, the mysticism of the East inserted itself deeply into the pragmatism of the West, producing an amalgam Greek in language but Asian in spirit which we call Hellenism. Cynicism

Even before Philip and Alexander had arrived on the Greek scene - the constant warring among the Greeks during the latter part of the 400s BC (the Peloponnesian Wars), the hunger of Athens for power and dominion over its neighbors, the treachery of some of Athens’ own leaders (Alcibiades), and ultimately the political and economic humiliation of Athens at the end of the 400s BC had produced rather widely a general sense that things were not right in this great city. The sophistry of many of Athens’ teachers, the greed and self-concern of her politicians, and in general the moral relativism that set in as everyone just supposed that there was little to be done with the way things had developed – all contributed to a mood that we today would term ‘cynicism.’ However ... it is important to note that what we today call cynicism had more to do with the ancient Greek philosophical school of Skepticism than it did with early Cynicism. Though Greek Cynicism took a very dim view of the Greek quest for wealth, status and power, it took a quite positive view of the Greek quest for knowledge. Thus Greek Cynicism was not at all cynical concerning the importance of the human quest for knowledge! Such cynicism belonged to Skepticism! Interestingly, it would be an oddball philosopher who would most graphically point up the moral deterioration of Athens in not only his teachings, but also his strange and offensive lifestyle. Diogenes of Synope, in fact, would be the source of the term ‘cynicism,’ a term which lives on with us still today. Diogenes of Synope (c. 412 to 323 BC). Diogenes, who was a contemporary of Plato and Aristotle, is considered the founder of the philosophical school of Cynicism. Diogenes felt that the happiest life is one in which we live our simplest – in accordance with the most basic ways of nature. Diogenes had seen too much evil come from the Athenians' growing love of money, status and power – and took a militantly hostile position against such things, mocking those who chased after them. Diogenes noted that animals, such as a dog, live quite contented and far more honorable lives than man without having to have the various material and psychological adornments of civilization that we think are so necessary for life. Some said that his at times vulgar, ascetic life indeed seemed to resemble more that of a dog (dog in Greek is kuon or kyon) than a man! Thus his philosophy eventually became identified as that of the kyon or ‘cynic.’ Diogenes began to look to inner or personal integrity as a substitute for lost public integrity (which had once been the focus of the moral life in Greece). Crates of Thebes. Crates was one of Diogenes' students who gave away his fortune in order to follow the simple ways of his teacher – in order to help others free themselves from the bondage to the kind of materialism that gripped at Greek society in his days. Crates was a kindly and generous individual who had a more loving and less reproving way about his cynicism – which endeared him to many Greeks and won a number to the cause. Skepticism

Basically skepticism is an intellectual position which followed Hellenism down the road of disillusionment with its former idealism or belief in lofty absolutes open to human understanding. Skepticism doubted that anyone was ever able to know the "truth" in itself. According to Skepticism, we can know only what our senses seem to perceive about the outer appearances of things and what our own inner reason can make of such sensory information. But we have no way of knowing for sure if any of our impressions or understandings are real or true. We are cut off from what we observe and study by our own separate existences. Skepticism takes a view on life quite opposite from such philosophers as Socrates and Zeno of Citium, who felt that knowledge was not only attainable but was also the highest attainment of our lives. To Socrates and Zeno, to know was to live in a state of happiness. Skeptics arrived at their more negative observations about life probably because too much of what they had hoped to be true about life simply was not working out for them in those confusing and troubled times of Greece's internal bickerings and Athens' moral decline. They, like the Stoics, tended to take a quietistic position about life - though unlike the Stoics their quietism included the intellectual life as well as the active life. Interestingly it is Greek skepticism rather than Greek cynicism that comes the closest to matching what we today call cynicism.  Pyrrho of Elis (ca. 360-270 BC).

Pyrrho is considered the founder of the Greek school of

skepticism. He was the first to break seriously with the

intellectual tradition of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in their quest

for knowledge. Not only did Pyrrho feel that true knowledge was

unattainable, but he felt that people are freed to live a truly happier

life if they do not frustrate themselves with pointless intellectual

pursuits, but learn to live through emotional self-discipline in a

state of contentment with things as they simply present themselves to

us. Pyrrho of Elis (ca. 360-270 BC).

Pyrrho is considered the founder of the Greek school of

skepticism. He was the first to break seriously with the

intellectual tradition of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in their quest

for knowledge. Not only did Pyrrho feel that true knowledge was

unattainable, but he felt that people are freed to live a truly happier

life if they do not frustrate themselves with pointless intellectual

pursuits, but learn to live through emotional self-discipline in a

state of contentment with things as they simply present themselves to

us.His answer to the accusation that his theories on life left us with no moral absolutes was simply that we ought to live by time-honored traditions that seemed to have worked out for us over the long run. While we could never state with absolute certainty that such traditions were ultimately true or good, they seemed to have proven themselves in their simple workability. That ought to be a sufficient reason for following them. Certainly to Pyrrho, following traditions was a lot safer than going after new, radical ideas that had only untrustworthy intellectual reason to justify themselves. Thus a conservative social agenda tended to go with this early skepticism. But ultimately Pyrrho's ethics were built more on personal social or cultural taste than on any powerful set of ethical directives. In the end there was nothing to keep a skeptic from disavowing all intellectual standards - and simply following a life of wantonness. Epicurus (342 to 270 BC) and Epicureanism

Today

of course we identify Epicureanism with a fancy pleasure-seeking

lifestyle founded on the doctrine of "eat, drink and be merry." Today

of course we identify Epicureanism with a fancy pleasure-seeking

lifestyle founded on the doctrine of "eat, drink and be merry."Certainly Epicurus (342-270 BC), the founder of the philosophy that bears his name, advocated the pursuit of pleasure. But in his definition of pleasure he intended something that had little in common with what we today so often identify as pleasure. In keeping with the traditions of Greek philosophy in early Hellenistic times, he understood pleasure as attaining freedom from the pains and hurts of life through the practice of virtuous living. However, unlike Socrates, he did not feel that virtue was a good in itself, worthy of devotion because of its superior qualities. He never looked deeply into the question of virtue's great, even divine, qualities. Rather he recommended focusing on living a virtuous life because it was able to produce pleasure--freedom from pain. It was in the ability to produce pleasure that virtue achieved its worth. Virtue was not the highest good. It was merely the means to the highest good, which was pleasure. Still, even though he himself understood pleasure in its nobler philosophical sense - in keeping with a residual attachment of Greek philosophy to traditional ethical standards - it was an easy step away from such lofty definitions of pleasure to the definitions we associate with Epicureanism. Indeed such a thing seemed to have developed quite quickly among his followers, for criticisms were soon recorded that his philosophy was providing people with the rationale for profligate living. The problem is - and remains to this day - that the Epicurean definition of pleasure was quite a subjective one. Since it was not really anchored in some loftier ethical standards it was easily coaxed into the understanding that whatever a person craves is the ultimate good for that person. There was nothing intrinsic within his philosophy that could hold pleasure-seeking to nobler human behavior. He also believed that we should focus our energies and thoughts on the material life immediately before us - and not waste time speculating about life after death. To him there probably was no such existence. In part this was due to his materialistic-atomistic cosmology (much like Democritus') which saw life as a result of atoms moving through space in such a way to form the stars, planets, the earth, and all upon the earth, including ourselves. This process was all determined by mechanical laws - not by any kind of gods. Stoicism

Stoicism was an intellectual movement that through its founder, Zeno, had its origins in Cyncism. But Zeno carried the idea of a retreat from crass materialism into loftier, mystical directions. Basically Stoicism extolled the idea of personal self-mastery, in particular of the mind over the body, and especially as the mind was led to contemplate the higher realities of the Logos, or the ultimate reality behind mere appearances. The East’s impact on Hellenism through Stoicism. Stoicism also represented the move toward a synthesis of Greek and Eastern thought. Indeed the leaders and scholars of Stoicism were almost completely individuals brought up outside the classic Greek heartland. Zeno, for instance, was of Phoenecian descent. Though Stoicism was originally formed in Athens by Zeno, very early on the movement developed most profoundly in such hellenistic centers as Alexandria (Egypt), Tarsus (Northwest Syria) and Rhodes (an island off the coast of southwest Asia Minor). Finally, it was only when (centuries later) Stoicism was mixed with the Roman temperament that it took on major importance, even dominance, as a philosophy in the Hellenistic-Roman Empire.  Zeno of Citium (336-264 BC).

Zeno, sometimes called ‘the Phoenecian’ was born in Citium in

Cyprus. But he came to Athens as a young man and lived there for

the rest of his life – without ever becoming a citizen of Athens.

He studied in the various philosophical schools of Athens and under

different masters (including the Academy that Plato had founded

earlier). For a time he was most attracted to the Cynicism of his

teacher Crates – and eventually began to teach the subject in the

Painted Stoa (Porch) in the Athenian market. [It was from his

teaching in the Stoa that the name for his philosophy, Stoicism,

eventually developed.] Zeno of Citium (336-264 BC).

Zeno, sometimes called ‘the Phoenecian’ was born in Citium in

Cyprus. But he came to Athens as a young man and lived there for

the rest of his life – without ever becoming a citizen of Athens.

He studied in the various philosophical schools of Athens and under

different masters (including the Academy that Plato had founded

earlier). For a time he was most attracted to the Cynicism of his

teacher Crates – and eventually began to teach the subject in the

Painted Stoa (Porch) in the Athenian market. [It was from his

teaching in the Stoa that the name for his philosophy, Stoicism,

eventually developed.] But he added his own touches to the teachings of his master Crates – especially additions that had quite Eastern elements in them. In the uniqueness of his teachings he truly set out a new philosophical course – a blending of Greek philosophy and Eastern mysticism. No writings of his have survived down to us today – though we have quotes of his and descriptions of some of his ideas by ancient historians, the most notable being Diogenes Laertes. In short, we have only the broadest outlines of his thought available to us today. We know that his interest was primarily ethical – in the manner of Socrates, whom he supposedly honored greatly in his teaching. He, like Socrates, was quite confident of the powers of disciplined human reason to secure both deep insight into the cosmos and happiness in a person's own life. That confidence was clearly based on his belief in the supreme existence of Divine Reason (the Logos), the ultimate reality behind mere appearances. He taught that human mind could – and most certainly should – attach itself to this Logos in pure devotion. He taught further that the only path to human happiness for a person came through complete personal self-mastery, in particular of the mind over the body, and especially as the mind was led to contemplate the higher realities of the Logos. Zeno taught his students to seek the ability to quiet the body's cravings so as to become totally focused on this devotional union with the Logos. This quieting of the body – and of the mind – furthermore was expected to be possible (importantly so) in the face of particularly difficult human circumstances. This ‘quietism’ ultimately became the hallmark of the Stoic. The development of the physical sciences

Not all Greeks (or Hellenists) took a negative attitude about studying the immediate world around themselves. The empirical traditions established by the Greek natural scientists (such as Democritus and Aristotle) continued to be followed by a number of notable individuals. Euclid (fl. 300 BC). Euclid taught mathematics in Alexandria, Egypt, and is even today considered the "father" of Western geometry. His work was clear and precise and well accepted in his days. Indeed, his writing Elements was used down into modern times as the major text on the subject of geometry. But we know little about him personally except through his many preserved works, especially the all-important Elements.  Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310-230 BC). Only through references from Archimedes (in his Sand Reckoner

of 212 BC) and Plutarch do we have knowledge of this amazing ancient

scientist. We know that Aristarchus had a much greater vision of

the universe than did his contemporary world and that he put forth some amazing observations (amazing for his time, anyway). As a young

man he published a work that declared that the sun was 19 times the

size and distance of the moon (actually the figure is about 400 times

the size and distance) – something that seemed to defy the common sense

of his times that the sun and moon differed only in the intensity of

their light, not their size and distance. Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310-230 BC). Only through references from Archimedes (in his Sand Reckoner

of 212 BC) and Plutarch do we have knowledge of this amazing ancient

scientist. We know that Aristarchus had a much greater vision of

the universe than did his contemporary world and that he put forth some amazing observations (amazing for his time, anyway). As a young

man he published a work that declared that the sun was 19 times the

size and distance of the moon (actually the figure is about 400 times

the size and distance) – something that seemed to defy the common sense

of his times that the sun and moon differed only in the intensity of

their light, not their size and distance.An even more startling observation arose from his calculation that the sun was much larger than the earth and therefore the likelihood was that the smaller body (the earth) revolved around the larger (the sun) rather than the reverse. This was the first known pronouncement of the heliocentric theory (the sun being the center of things) in opposition to the universally held (at least in Hellenistic society) geocentric theory (the earth being the center of things). Aristarchus's heliocentric theory was ridiculed at the time because it seemed so obviously wrong! Nonetheless, his work was defended and promoted by Seleucus of Babylonia a century later. But ultimately it came to naught in Western thinking.  Archimedes (287-212 BC).

Archimedes was a scientist in the way we understand the term: he

combined his love of mathematical theory with a zeal for

experimentation. Consequently, he produced a number of major

insights into the realm of mechanical engineering and physics ...

including most importantly The Sand Reckoner.

He was a major contributor to the study of geometry and the science of

weights and measures. He also came very close to inventing the

calculus (that honor ultimately went to Newton 1,900 years later). Archimedes (287-212 BC).

Archimedes was a scientist in the way we understand the term: he

combined his love of mathematical theory with a zeal for

experimentation. Consequently, he produced a number of major

insights into the realm of mechanical engineering and physics ...

including most importantly The Sand Reckoner.

He was a major contributor to the study of geometry and the science of

weights and measures. He also came very close to inventing the

calculus (that honor ultimately went to Newton 1,900 years later). He also was famed in his days for the inventive devices he provided his native city of Syracuse (Sicily) in its (ultimately unsuccessful) defense effort against the besieging Romans.  Eratosthenes (ca. 276-192 BC).

Eratosthenes was the librarian of the great museum/ library of

Alexandria. Based on the knowledge that 1) at noon at the summer

solstice the sun shone directly down a well in Syene (Aswan) Egypt and

2) calculating the angle of the shadow that the sun made over a

vertical pole at Alexandria Egypt at exactly the same moment and 3)

having an accurate measure of the distance between the well at Syene

and his rod at Alexandria, Eratosthenes estimated the earth's

circumference at 24,660 miles – only about 200 miles less than the

actual measure! He also claimed that a person could sail around

the earth and arrive back at his starting point, provided that he never

changed course along the way. Eratosthenes (ca. 276-192 BC).

Eratosthenes was the librarian of the great museum/ library of

Alexandria. Based on the knowledge that 1) at noon at the summer

solstice the sun shone directly down a well in Syene (Aswan) Egypt and

2) calculating the angle of the shadow that the sun made over a

vertical pole at Alexandria Egypt at exactly the same moment and 3)

having an accurate measure of the distance between the well at Syene

and his rod at Alexandria, Eratosthenes estimated the earth's

circumference at 24,660 miles – only about 200 miles less than the

actual measure! He also claimed that a person could sail around

the earth and arrive back at his starting point, provided that he never

changed course along the way.He likewise catalogued nearly 700 stars. And he devised a system of calculating prime numbers. Hipparchus (fl. 145-130 BC). He was one who put forth strong arguments against the heliocentric theory of Aristarchus – on the grounds that a mathematic system of eccentrics and epicycles seemed to account more logically for the movement of the heavens (he had a very strong influence on Ptolemy who took up his work several centuries later) and did not suffer from a theory which required the earth to move. Such a theory to Hipparchus flew solidly in the face of common sense. But in other respects, he was a very accomplished mathematician, geometrist and astronomer. He rejected astrology and based his work solely on rigorous observation – that avoided metaphysical speculation. He was highly instrumental in the creation of trigonometry – including the formula for spherical triangles. He created a star catalogue which was quite accurate – and which listed almost 1000 stars. |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges