|

|

|

|

The Roman contribution to Western material and intellectual culture:

A profound sense of 'order' in all of life The Romans, coming along behind the Greeks (after defeating the Greeks militarily in 146 BC and turning Greece into a Roman province), put into effect a wonderfully ordered material civilization. This civilization indeed gave witness to the power of human reason or human engineering to work with the natural world in producing a place that people often thought was perfection itself. Roman civilization bore out the hope of the Greeks – by giving the West a practical example of the orderly life. The Romans were not intellectual innovators – as the Greeks were with their powerful philosophies. Rather, the Romans were powerful administrators – such as the Greeks themselves were never able to be. The Romans, with their sense of legal or administrative order, put the Greek ideas to work in life. Probably had not the Romans done so, the Greek contribution might itself have been put aside with its own growing cynicism and skepticism. Thus the Romans contributed immensely to (materialistic) Western civilization by demonstrating clearly that orderly cooperation with nature could produce amazing results. The on-going influence of Hellenistic thought

Yet even under the practical-minded Romans, Western philosophy continued to develop. But Roman philosophy tended to follow the lines laid down by Hellenistic Greece in the two previous centuries. Indeed, as once Eastern thought captured its Greek conquerors centuries before, now Greek thought began to capture its Roman conquerors. Thus did Greek Platonism and Stoicism continue to draw Western philosophy forward, though now under Roman patronage. Indeed despite Roman political ascendancy, the Greek-speaking eastern provinces of the Roman Empire continued by their own right to be vibrant and at times even dominant cultural-intellectual centers within the Roman Imperium. The origins of Rome

The story of the rise of Rome from a group of hills hosting a number of Latin-speaking tribes--to the position of ruler of all the Mediterranean lands and Europe north and west beyond the Alps--is a story of both myth and powerful fact. It is a tribute to their doggedness as military entrepreneurs and the giftedness of their military leadership. But it is no less a tribute to their organizational mindset, for they were able to rise above the tribal mentality (all members of society related by blood and members of a single genealogical line) and instead create a monumental society built on a mutual respect for a Code of Law that made all who came under its authority coequal partners in the Roman social experiment. Indeed Rome tried to be a society of Law rather than blood. And by and large the Romans succeeded in this enterprise, leaving a legacy in the West, that exists to this day: the understanding that society ought to be a community of laws, not of personalities or special social groups. Of course that is a very high standard to which to aspire ... or to maintain if achieved. Ultimately Rome itself could not maintain such a lofty concept ... and declined as it left that standard behind it. But the legacy remained and still serves to this day as the ideal of all Western societies ... whether actually achieved or not. As a social organization Rome passed historically through a number of phases: from a Latin principality (from their mythical origins to sometime in the 500s BC), to a monarchy under the Etruscans (during the 500s), to a Republic with a sometimes broader and sometimes narrower popular base, to an Empire based on the influence and power of the military. The Romans were conquerors who tended to be respecting of the cultural habits of the people they conquered. Indeed, with respect to the Greeks, they actually stood in awe of Greek culture, and not only borrowed heavily from it, but held it up as an ideal even during their own political ascendancy over the Greek world. Citizenship was conferred widely on those they conquered, which made their rule a bit lighter but more deeply founded outside Rome itself. The Republic

We tend to idealize the Republic – probably a bit caught up too much in the idealized vision of the Republic put forth (and still read today) by Cicero, who wrote even as he saw his beloved Republic coming to an end. Actually for most of its days the Republic was run by a privileged elite, drawn from the very old aristocratic patricians and from upstart plebians who were able to attain incredible wealth (usually at the expense of the other commoners) and status through intermarriage with the patricians and through acquiring a place in the Senate, which they guarded jealously. There were Tribunes, selected for short terms (one year) to watch out for the interests of the commoners, plus the Assembly, which was supposed to give voice to commoners' interests. But by and large during the Republic, the Senate did what it could to keep a tight hold on the political life of the Republic. Cultural-religious pluralism

Rome was tolerant of the social and cultural "pluralism" within its borders – as long as everyone showed due respect to Roman authorities and their gods. When the authorities themselves posed as gods this all became quite curious. But for the most part everyone was willing to play along with the Roman thing. Morally and ethically, Rome didn't reach deeply into the private hearts of its subjects. That belonged to their local gods and religious traditions. |

|

|

The first Italians

Three groups of Italian-speaking tribes – the Latins, the Umbrians and the Samnites – migrated down into Italy from the north just about the same time that the Dorians were overruning Greece (around 1000 BC). They too conquered with iron weapons, thus introducing the iron age to Italy. They eventually settled into the mountainous center of the Italian peninsula and in the west-central lowlands facing the Mediterranean Sea. Basically these peoples were farmers, cattle raisers and sheep herders.  The Etruscans

This wave of conquest and settlement was followed in around 900 BC by another – that of the Etruscans, who invaded central Italy from the east. The Etruscans established ascendancy over the Italians, and reached the peak of their power during the mid-500s BC. They established cities and a high order of a material civilization – not unlike the Greeks. The Founding of Rome

The actual origins of Rome itself are submerged beneath a heavy overlay of patriotic myth – and thus it is hard to get at the "facts." The town was created through the joining of a number of settlements found among the "seven hills" located along the middle Tiber River. These eventually came to comprise early Rome. Myth says that two Latin brothers, Romulus and Remus, were responsible for laying out the foundations of Rome. But a Etruscan royal line (the Tarquins) seems to have established itself in Rome in the 500s BC. It ruled the town and environs – though it was by and large a positive rule, building up Rome with an extensive city wall, public buildings and public water and drainage works and bringing commercial prosperity to Rome. It also developed a very effective military force. The Etruscans also gave Rome its first experience in representative government, laying out Rome’s basic governmental framework of several councils (comitia and their leaders or consuls) to oversee Rome’s various civil and military functions. It was at this time that a body of local ‘first citizens’ or Roman patricians grew in prestige and influence within Rome itself. The Etruscans also gave Rome its first experience in representative government, laying out Rome’s basic governmental framework of several councils (comitia and their leaders or consuls) to oversee Rome’s various civil and military functions. It was at this time that a body of local ‘first citizens’ or Roman patricians grew in prestige and influence within Rome itself. The Greeks and their influence

We have already seen that the southern part of Italy, including Sicily, was settled heavily by the Greeks. Here Greek civilization attained great heights of achievement. It certainly, along with the Etruscan culture, left a strong material legacy among the Italians – though the latter held tenaciously to their distinct Italian language. |

Etruscan warrior or Mars

(mid 400s BC) bronze

Florence, Museo

Archeologico

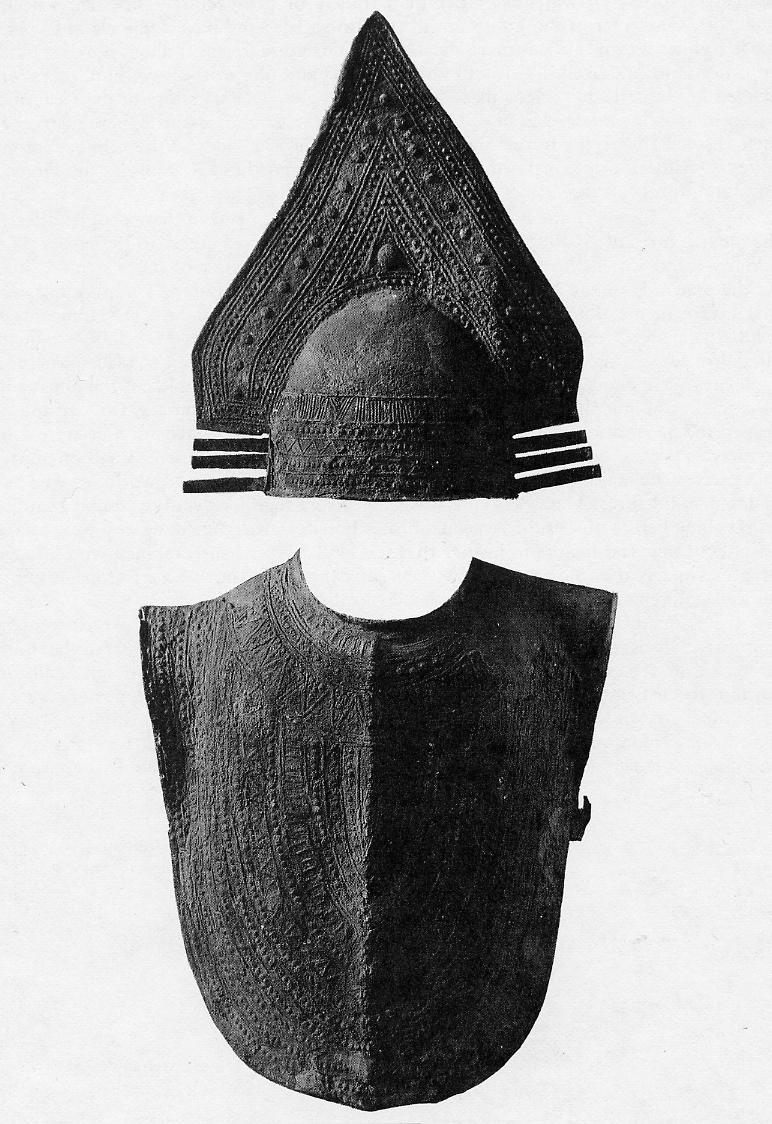

Villanovan (Etruscan) helmet

and body armor

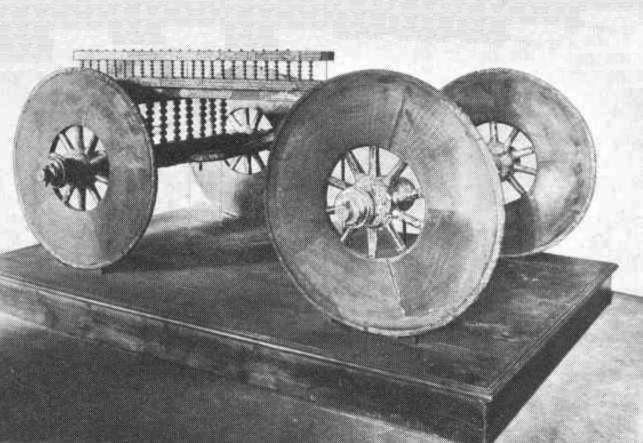

Etruscan horse-drawn

chariot

Museo Civico di

Como

Ambush of Prince Troilus

by Achilles — Detail of painted wall

Etruscan Tomb of the Bulls,

Tarquina (540-530 BC)

Etruscan Sarcophagus of

the Spouses (late 500s BC) polychrome terra cotta — from

Cerveteri

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

Two Etruscan

Warriors

The

"Capitoline" she-wolf

(early 400s BC and possibly Etruscan) bronze

(the twins, Romulus and Remus,

probably date from the

late 1400s)

Rome, Palazzo dei

Conservatori

|

|

Early rise among the Latins

Around 500 BC Rome began its expansion by entering into alliance with other Latin cities against Etruscan dominance. But gradually over the next century and a half, Roman leadership within the alliance turned to dominance within the alliance (much as Athens was doing at about the same time). Against the Etruscans

With this growing power, Rome put increasing pressure on the Etruscans. Finally in 396 BC the Romans overran and destroyed the Etruscan capital at Veii. Henceforth the Etruscans would remain troublesome – but no longer a major threat – to Roman designs in Italy. The Celts

Absorption of the fellow Latins and the Samnites

In 338 BC a number of Latin cities rose up in revolt against Roman dominance. But the Romans responded swiftly both militarily in crushing the Latin uprising and diplomatically in extending Roman citizenship to the conquered Latins. Also, the fellow Italian Samnites in the mountain valleys of central Italy tried to block Roman expansion through a series of wars or uprisings beginning in 343 BC – though they too (along with some Umbrian, Etruscan and Celtic/Gallic allies) finally fell to Roman power at Sentinum in 295 BC. Relations with the Greeks in Southern Italy

As we have already seen, the Greeks had been settling southern Italy for centuries. For a while the two groups were cooperative, with the Romans in fact adopting many Greek cultural features – many of them transmitted to the Romans by the Etruscans during the monarchy. Notably there was the Roman adoption (with many modifications) of the Greek alphabet. Indeed, by 300 BC the process of Hellenizing Roman culture was moving rapidly forward – especially through the romanticizing of Alexander and his exploits, which led the Romans to idealize Greek power, Greek culture, Greek philosophy, Greek religion. But Roman political expansion and the question of which of the two powers was to dominate southern Italy was destined to produce friction with the Greeks in Italy. A Greek reaction – joined by some Latin allies also resenting Roman dominance – finally took form around the ambitions of King Pyrrhus of Epirus, who (equipped with some awesome elephants) managed at first to defeat the Romans in several battles. But these victories were so costly to Pyrrhus ("Pyrrhic victories") that it depleted Greek power and discouraged their Latin allies – to a point where the Romans were finally able to defeat Pyrrhus in 275 BC at Beneventum. Quickly thereafter Roman mastery of southern Italy became complete. But there was still a mighty Greek presence in eastern Sicily in the form of prosperous Syracuse. Against Carthage

Carthage was a great sea power located in Africa just across from Sicily, as well as in western portions of Sicily itself. At first competition for the Carthaginians came from the Greeks (during a century-long war from 367; the Romans were fairly friendly to the Carthaginians). But after the defeat of the Greeks by the Romans, the Romans and Carthaginians were left facing each other for ultimate dominion over the seas around southern Italy and the lands around the western Mediterranean that began to interest the Romans. The clashes came in the form of a series of wars – the Punic Wars – fought between Rome and Carthage over the next 120 years (264-146 BC). Carthage was a formidable opponent, with a powerful navy and a huge, prosperous urban population to put muscle to their war effort. But Rome had an experienced, battle-tested land army. The First Punic War (264-241 BC) linked Hieron II of Syracuse with the Romans in expelling the Carthaginians from Sicily. The Second Punic War (218-201) started when the Carthaginian leader Hannibal Barca attacked Roman Saguntum in Spain, then crossed the Alps with a mighty army and for 15 years held off Roman efforts to dislodge him from northern Italy – until Rome decided to take the war to Carthage itself, where at Zama (202 BC) Hannibal lost his only battle (but also the war) to the Roman general Scipio "Africanus" (considered still today as one of the best generals in history). Carthage was stripped of its war-making powers as a result of the war. Tragically, the Roman patricians (upper-class) were jealous of the popular Scipio and brought him to trial for unfounded charges of bribery and treason, resulting in his retreat in disgust from Roman public life.

Hannibal Barca Scipio Africanus

The Third Punic War (153-146) occurred when the leading families in the Roman Senate decided that it wanted no further competition from a fast-reviving Carthage, found an incident that permitted them to return to war, eventually marched on the city, and after a 3-year seige, burned it to the ground. Carthage was destroyed and Africa (the region around Carthage) became a Roman province. Against the Greeks

Philip V of Macedonia unfortunately had chosen to ally himself with Hannibal during the Second Punic War and Rome. Once Hannibal had been defeated, The Romans turned their attention to Philip and led a rebellion of Greek states against the Macedonian monarchy in 214 BC. This drew Rome deeply into Greek affairs and a number of wars involving Rome in Greece – and also in Macedonian Asia Minor and Syria under Antiochus. Rome "liberated" these Greek cities and placed them under Roman protection – as Macedonian power was chipped away at. But eventually Roman dominance bred its own opposition in the Greek East. Perseus of Macedonia tried to rally these Greek sentiments – but the Romans quickly marched out to defeat him at Pydna (168 BC). The Romans did not follow up their victory in such a way to discourage further thoughts of rebellion and in 148-146 BC a final war brought Macedonia under full Roman dominion as a Roman province and the rest of Greece under the full "protection" of the Roman governor in Macedonia. In Asia Minor and Syria the Romans continued the pretense of a mere "protection" placed over local Greek power – but made and unmade kings and rulers at will. Roman rule was in fact complete in these regions. |

|

|

The Monarchy and the Comitias

The Tarquinian monarchy in Rome shared its power with several assemblies or comitias whose power increased/decreased over the centuries: the Comitia Curiata or popular assembly of all freemen, the Comitia Centuriata or military assembly, and the Comitia Tributa or tribal assembly (presided over by 10 Tribunes). There was also the Senate, a council of elders serving for life as advisors to the king – a council which grew in power and eventually took the lead in the political life in Rome after the overthrow of the monarchy (traditionally in 509 BC). The Patricians and the Plebians

There were among some of these early Romans a number of families of "worthier" nature--the "patrician" families – marriage into which offered a preferrential placement in the Roman scheme of things. The poweful Senate of course was dominated by these patrician families Yet simple membership in any of the families of the permanently settle Romans – the common citizens or "plebians" – accorded itself some important rights in the life of the Roman community. Indeed, there was a most unusual openness about Roman life, its readiness to adopt others into its communal life – even freed slaves. In fact a freed slave living in Rome automatically became a Roman citizen. The Republic

According to tradition, the Traquinian monarchy was overthrown in 509 BC. The patricians were behind this action and it represented the victory of the traditional Latin agrarian gentry over the newer commercial groups closely connected to the Etruscans and Greeks through trade. It marks a time of decline of Etruscan power – and the growth of Roman military expansion. With the new Republic, two patrician Consuls (serving one-year terms) replaced the king as the head of the Senate and the military Centuriata. But eventually (through plebian pressures) a number of Tribunes, representing the interests of the plebs, were accorded both the power to protect the poorer Romans and certain veto powers over the acts of the aristocratic Republic. There were a number of other Roman officials, the Quaestors (judges), the Censors (tax officials), Aediles (public works supervisors) and others whose powers – along with the whole governmental structure – were carefully defined in the 12 tablets of the Roman constitution (ca. 450 BC) – posted in the Forum for all to see. All Romans knew these laws well. |

|

|

The dominance of the Roman Senate

This rise from an expansive agrarian power in west-central Italy to the point where Rome now commanded the fabulous civilizations that ranged around the Mediterranean (Macedonian Egypt, however, had not yet fallen to Roman rule) – all this change was bound to have a profound effect on the internal disposition of Rome. Over time, but particularly during the wars with the Carthaginians, the Roman Senate had become the center of all Roman power. It was a club of old patrician families and new plebian wealth (new landowners) which closed its ranks and became a ruling oligarchy. Meanwhile rising taxes and competition from slave labor were bringing the Roman commoners to ruin. Roman power, especially the power of the Roman military, was built on the services of these commoners. Something drastic needed to be done to save Rome from collapse or revolution. The Gracchi (133-121)

Marius (108-100)

A mix of events then brought to the fore a capable military leader, Gaius Marius, who through his important military victories became so influential that he was repeatedly elected consul. On numerous occasions he moved to clean out political corruption or incompetency in the army and public administration, save Rome itself from invading barbarians, and institute reforms in the army to make it more democratic and higher in morale. But perhaps the most important effect of Marius was in the way that he brought the military forward as a key arbiter of public affairs. The "Social War"

This title describes various events that accompanied a shifting of power within Roman society. As usual, much of the trouble was between the patricians or the "equestrian" class dominating the Senate and controlling the wealth of the countryside and the populare or common citizens demanding greater influence in the life of the Republic. This conflict was greatly complicated by the demands of the Italian allies for full Roman citizenship (entry to which had been tightened up since it had become so much more profitable since the Punic Wars). Marcus Livius Drusus attempted to work a compromise both with the Roman commoners and the Italian allies – but suceeded only in alienating the Senate which vetoed his reforms. He was subsequently assassinated (91 BC). Once again reform was set aside. Meanwhile, Roman armies first sent out to put down the Italian revolts met with defeat. Eventually Marius was brought back to military service, along with a new figure, Sulla. They turned the military tide – but only as the Roman budget was depleted. The Senate ultimately decided to extend citizenship (88 BC) – though the Samnites continued to stand apart, hostile to Rome. Sulla

But Marius took the same course as Sulla and entered Rome with his army, massacred some his opponents, and was elected Consul for the 8th time in 86 BC. But he died a few weeks later. Civil war spread throughout Italy. In 82 BC, with his military campaign complete in Asia, Sulla returned to Italy and entered Rome again at the head of his army. Once again the Senate stood restored to dominance in Roman affairs – and the enemies of the Senate were destroyed or scattered. Whole sections of land were transfered to his partisans. Having accomplished his "reforms," Sulla retired – though he died a few years later in 78 BC.  The slave rebellion led by Sparticus.

A reign of terror rested over the land--producing the semblance of

peace only through fear. Whole regions lay desolate. And in

73-71 BC the slaves (joined by the Roman paupers) even went into revolt

led by the gladiator Sparticus, conditions having become so bad.

Finally the Senate called on the very wealthy patrician, Marcus Licinius Crassus,

to suppress the rebellion. Crassus's legions chased down

Sparticus's rebel army, crushed the rebellion, and lined the Appian Way

with 6,000 crucified (hung on wooden crosses) bodies from Rome all the

way south to Capua (120 miles). The slave rebellion led by Sparticus.

A reign of terror rested over the land--producing the semblance of

peace only through fear. Whole regions lay desolate. And in

73-71 BC the slaves (joined by the Roman paupers) even went into revolt

led by the gladiator Sparticus, conditions having become so bad.

Finally the Senate called on the very wealthy patrician, Marcus Licinius Crassus,

to suppress the rebellion. Crassus's legions chased down

Sparticus's rebel army, crushed the rebellion, and lined the Appian Way

with 6,000 crucified (hung on wooden crosses) bodies from Rome all the

way south to Capua (120 miles).Pompey

It was the army – no longer the Senate – that now directed Roman affairs. He left Rome in 67 BC and entered Asia, where he finally brought Syria to the status as Roman province and marched further east to the Euphrates River and the Caspian Sea. Caesar

In

the meanwhile, as a nephew of Marius, Julius Caesar became spokesman

for the pro-Marius or popular party in Rome. In Pompey's absence

Caesar became advocate of the restoration of much of the popular

reforms of Marius. In

the meanwhile, as a nephew of Marius, Julius Caesar became spokesman

for the pro-Marius or popular party in Rome. In Pompey's absence

Caesar became advocate of the restoration of much of the popular

reforms of Marius. Caesar also put his administrative genius to work to undertake popular public works projects ranging from public games to new roads. He also pushed for the extension of the Roman citizenship to the Italians of north Italy. And he engaged in political maneuvering to bring the popular Crassus to his side. Finally he was able to secure for himself the governorship of Spain – an important stepping stone to preeminence alongside Pompey. Cicero

Cicero was a self-appointed spokesman for conservative middle class interests – neither in favor of the patrician Senate nor the urban mobs that threatened the old Republic. Cicero's election as Consul in 63 BC was in testimony of his appeal to this middle class, plus the willingness of the patrician Senators to back him in fear of a worse fate from the populist radicals. He was opposed by Cataline, a bankrupt patrician who conspired to engineer widespread discontent among a whole spectrum of people within the Republic (from the supporters of Sulla, to slaves, to even the people recently brought by conquest into the Roman order), in order to make himself dictator. Cicero organized the Republic's response in to this strange and ill-fated revolt (63 BC) and had Cataline and many of his supporters put to death. The Triumvirate

As Pompey made his return from Asia in late 62 BC Rome was wondering what would happen next. Through the political maneuverings of Caesar and the Senate a deal was struck whereby Rome would come under a three-way power sharing arrangement. In 60 BC Caesar returned from Spain to become Consul. Crassus became the other Consul and commander of an army sent to Syria to seek fame and fortune. Pompey became the "head" of the triumvirate, received land for his loyal troops, had his diplomacy in Asia confirmed by the Senate, and became governor of Spain. Further, Caesar was given military command of Celtic Gaul, both Gaul on the Italian side of the Alps and Gaul to the north beyond the Alps. This would be Caesar's opportunity to bring fame and power to his career. Meanwhile Cicero saw his ideal of a revitalized middle-class Republic being undone with these developments. He also knew that his career and possibly his life was over. The next year, when charges were finally brought against him, he fled for his life. Caesar's conquest of Gaul (58-51 BC) and his invasion of Britain are well-known achievements of Caesar's, made famous because he published his memoires as a means of letting the Roman citizenry know of his great exploits. With Pompey and Caesar away, chaos began to reign in Rome. Pompey returned, restored order and had Cicero recalled with his sentence set aside. But Cicero misread his own popularity and overstepped his power in again working against the triumvirate. The big three met again in 56 BC, renewed their alliance, and Cicero announced his retirement from politics. Caesar's rise to power

But three years later Crassus was killed in battle against the Parthians (Persians) – and now a two-way power division existed between Caesar and Pompey. Also riots and general disorder were increasing in the capital and in 52 BC even Cicero admitted to the need to confer extraordinary powers on the Pompey, now sole Consul. Pompey became flattered by his title, and by the attentions of the Senate, and was soon drawn into a Senate-inspuired conspiracy against Caesar. The plan was not to renew Caesar's appointment as Consul--and indeed to have him step down from his military command immediately. This would then require Caesar to return to Rome to stand for re-election without the military support that had by this time become all-essential for success in Roman politics. Caesar refused. The Senate then expelled his supporters – and Caesar knew that he had to take drastic steps to save himself. In March of 49 BC he crossed with his troops into Italy, entered Rome at the head of his army (Pompey and the majority of the Senate fled to Greece) and became the sole ruler of Rome. |

|

|

Polybius (ca. 200 to 118 BC)

Polybius was a Greek scholar and politician, who wrote a history about the rise to power of Rome. When Macedonia was defeated by Rome in 168 BC. he was brought as a political prisoner to Rome. But he was able to use this misfortune to intervene on behalf of his Greek compatriots to secure fairly gentle treatment by the Romans of the Greeks (the Romans tended to be quite impressed with Greek civilization anyway.) Living there another 18 years, and becoming part of the political circle of the powerful Scipio family, he became familiar with a number of Roman notables. Thus when he eventually wrote the story of Rome's rise to power (40 volumes covering the period up to the final conquest of Greece in 164 AD – with only the first 5 volumes having survived to today), he did so with particular insight. Lucretius (96 to 55 BC)

The Roman poet and philosopher, Lucretius (Titus Lucretius Carus), was a strong contributor to the Roman sense of material order. He was a naturalist in the tradition of Democritus and Epicurus – holding a very low view of the religion of his times. In his work De rerum nature (On the Nature of Things) he claimed that popular religion was the source of the worst superstitions and sources of human evil. Virgil (70 to 19 BC)

Virgil was a Roman poet and historian, creating for the Roman world an epic poem of the nature of Homer's Greek epic poems. In Virgil's Aenead he tells a tale of the founding of Rome - connecting the tale with the story found in Homer's Iliad. According to Virgil, Aeneas was a Trojan refugee who made his way to the shores of Italy, there to found Rome (a version very different from the older story of the brothers Romulus and Remus).

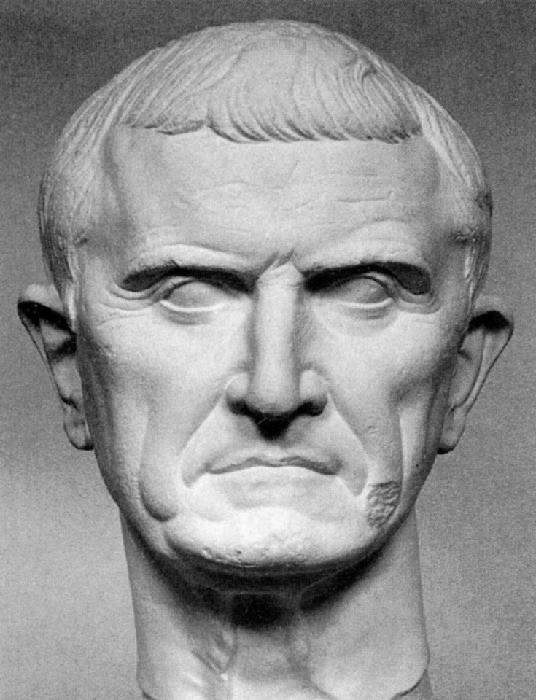

Polybius

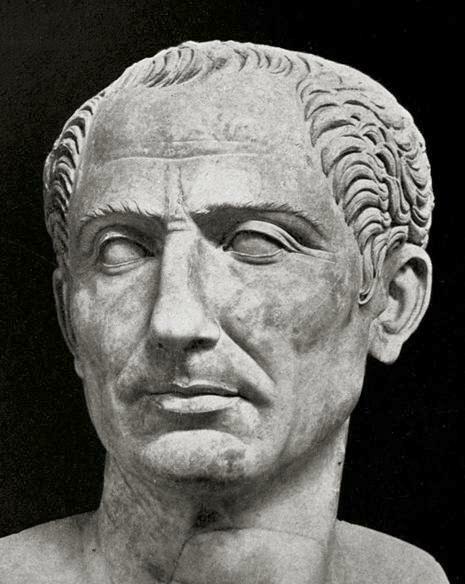

Lucretius

Virgil

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges