|

|

|

|

Princes and bishops consolidate their power

Princely rule was organizing itself into stronger political units. The previous invaders themselves added strong blood to the ruling lines of Europe – especially the adventuresome Normans. Princely rulers, such as the "Emperors" Frederick I [Barbarossa] (1152-1190) and Frederick II (1194-1250), gained enough of a hold over larger territories that they were able to offer some degree of peace and prosperity to the land in Germany, in France and in England. But the church, under the guidance of powerful popes, was just as active consolidating its power. The most notable of all these popes was Innocent III (pope: 1198-1216). Innocent wielded power greater than even the emperors themselves and used his power to marshal crusades to reshape the political landscape not only of Western Europe but also Christian Byzantium in the East. The investiture controversy

However the simultaneous strengthening of secular and religious authority produced some of its own new tensions. Powerful popes found themselves in contention with powerful princes, in particular with the Holy Roman Emperor. Princes felt that it was their privilege to make appointments of bishops to the church within their lands – a source of major political influence for them. The popes however felt that this power belonged only to Rome. A fierce "investiture" controversy thus broke out between church and state all through Western Europe. Rapid social development

The West was on the rebound materially. European commerce and trade soon began to revive, monasteries reformed as centers of learning, cathedrals began to be built and cathedral schools began to draw professors and students to form the nucleus of European universities. Most all this was due to the crusading of the Westerner in the Holy Lands help by Islam. The Cultural Impact of the Crusades

For two centuries after the year 1095 wave after wave of Christian crusaders arrived from the West to challenge the Muslim (and sometimes Christian Orthodox) East to bloody battle. This was not destined to last however, for Islam eventually got its act together. Under the pressure of the Western Crusaders, Muslims retook step by step the kingdoms that the Crusaders had established ... and by the late 1200s had succeeded in throwing the last of these Christians out of their feudal holdings in the Holy Lands. However – the Muslims did not at this point shut out the Christians from the Holy Lands, but instead invited them to come peacefully, as pilgrims ... and to trade. They did, they came – but not just to Palestine in the East but also the Spain in the South, where the Muslims opened up to them a new world of scientific knowledge and material culture. Here the best of Greco-Roman material culture had been preserved by the Muslims, who had noticed no particular contradiction between their religious faith and the material legacy of Greece and Rome. It was an eye-opening experience for the Westerner who came there to study. |

|

France

Chartres Cathedral - Gothic

design constructed largely between 1193 - mid 1200s

Stained glass window, Chartres

Cathedral (c. 1220-1230)

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame

de Paris (1163 - early 1300s)

Sénanque Abbey – Vaucluse,

France (1100s)

Cloister of the abbey church

Saint-Pierre de Moissac – Tarn-et-Garonne, France (late 1100s)

Nave, Cathedral of Amiens (c. 1220-1250)

The Low Countries (Dutch Belgium and the Netherlands)

Central nave, Cathedral of Tournai, Belgium (early-mid 1100s)

Germany

Eastern apse of the Cathedral of Spire, Germany (c. 1100)

The Dormition of the

Virgin

(1220-1230) Tympanium, Strasbourg Cathedral, portal of the south

transept

Bonn Pietà (c. 1300)

wood

Cologne, Rheinisches

Landesmuseum

Vaults, Cologne Cathedral (1248-1322)

England

Vaults of the nave, Exeter

Cathedral (c. 1280-1290)

Detail of a stained-glass window, Canterbury Cathedral (c. 1180-1220)

Spain

The Cathedral of Burgos

(1221-1260;

upper portion and bell tower, 1400s)

Facade, Church of Santiago de Compostela (the Porch of Glory) 1188-1200

|

|

Intellectual-spiritual stirrings

Thus contact with the Byzantine and Muslim East brought not only a new wealth in goods but also in new ideas – particularly through the rediscovery of the ancient Greek philosophers whom the West had lost touch with. Musicians, poets and spiritual reformers (like Francis) touched the hearts of Europe while university scholars touched their minds. Scholarship, especially within some of the monasteries, began to stir mightily. The late 1000s/early 1100s produced such learned figures as Anselm (1033-1109), Berengar (flourished late 1000s), Hugh of St. Victor (early 1100s), Peter Abelard (1079-1142) Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) and Peter Lombard (1100-1160). Anselm was a theological writer of the first order; Abelard was given more to an exploration of the earthly life; Bernard was a powerful organizer of the monastic system and Lombard put together a great devotional guide, Sentences. |

| Eventually new teaching orders, the Dominicans and the Franciscans emerged to meet a rising hunger for learning among the common people. The Dominicans taught with an eye to enhancing Christian orthodoxy among the people. But the Franciscans had more of a "spiritual" learning to bring to the people. In either case, both new orders were signs of the intellectual emergence of the West. |

Pope Honorius III confirming

by papal bull in 1217

the revised rule of the Franciscans

(he also approved the founding of

the Dominican order)

Dominican

"Blackfriars"

Franciscan

"Greyfriars"

A monk buying parchment from

a trader

The Royal Library, Copenhagen,

Denmark

|

Scholasticism

Soon

this hunger for learning, characterized by the founding of the

Dominican and Franciscan teaching orders, was pushing some of the

teachers into ever deeper intellectual inquiry. As ancient works of

Aristotle were reintroduced to the West from the Muslim East, scholars

began to gather at the new "universities" which were growing up out of

the cathedral schools. Here language, logic and science came under

rigorous study. Soon

this hunger for learning, characterized by the founding of the

Dominican and Franciscan teaching orders, was pushing some of the

teachers into ever deeper intellectual inquiry. As ancient works of

Aristotle were reintroduced to the West from the Muslim East, scholars

began to gather at the new "universities" which were growing up out of

the cathedral schools. Here language, logic and science came under

rigorous study.Scholars such as Thomas Aquinas were gathering at these universities to rediscover the full array of Aristotle's and Plato's writings – and other "pagan" or pre-Christian writers. Slowly their insights into life were not only broadening – but being refined by the tough intellectual disciplines of logic, mathematics, law, medicine, and astronomy. This all eventually became disciplined into the intellectual movement known as "scholasticism." |

|

The Campo of

Pisa

in the foreground, the baptistery,

1153-1300s; beyond that, the cathedral, 1063-1200s;

off to the right in the distance: the campanile (the famous "Leaning Tower of Pisa"),

1173-1350

The Church of Santa Croce,

Florence (1295-1413)

Interior, Baptistery of Parma,

1196-1260

View of the apse, Church

of Saints Mary and Donatus, Murano (Veneto, Italy) 1100s

Duccio di Buoninsegna –

Madonna

and Child with Saints

Obverse of the reredos for

the main altar, Cathedral of Siena (1298-1311) tempera on panel

Siena, Museo della

Metropolitana

|

A New Humanism Is Clearly Emerging In Italian

Art

| But

this epoch marks not only a flowering of the mind – but also of the

heart. The natural inquisitiveness that peace and prosperity

brought was met as much by a new exploration of the private world of

faith and spirit as it was by the new exploration of human reason. Musicians and poets touched the hearts of Europe with a new love for the world which God had placed them in. Thus the artist Giotto, though commissioned to paint religious art, designed his people to look real, very human and quite alive – not just formalized human icons who possess only symbolic existence. Giotto was a muralist and fresco artist famed for his life-like depictions of Biblical personages – the mark of one who studied the human make-up very closely. |

Giotto di Bondone

(1266-1337)

Giotto –

The Dream of Innocent III (late 1200s) fresco

Upper chapel, Basilica of

St Francis, Assisi

![]() For

more (much more!) of Giotto's works

For

more (much more!) of Giotto's works

Simone Martini –

Guidoriccio

da Fogliano (1330) fresco

Palazzo Pubblico, Siena,

Sala del Mappamondo

| Also ... Petrarch, Boccaccio, Dante, Chaucer wrote poetry and prose that also focused on human life as it is actually lived by real people around us – objects of interest (though not yet quite objects of reverence) in a world that had heretofore been focused more on the life beyond this earthly existence. |

|

Dante Alighieri, detail from

Luca Signorelli's fresco

Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374)

Francesco Petrarch -

by Andrea del

Castagno

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375)

Giovanni Boccaccio - by Andrea

del Castagno

|

Mysticim also develops ...

and new "heresies" (according to Church standards) also develop

|

Mysticism

Yet even as the world of the intellect expanded rapidly, the hearts of the Christian faithful still continued to seek, perhaps even more devotedly, a deeper, more vital personal relationship with God. Religious mystics, such as Meister Eckhart, Jan van Ruysbroek, Walter Hilton, Julian of Norwich, and Catherine of Siena, plumbed the depths of the soul and its relationship to God – and left records of those journeys for others to consider. Thus Christian mysticism flourished richly right alongside a growing humanism during these times. Heresies

To the distress of the church, contact with the Byzantine and Muslim East brought not only a new wealth in goods but also a new wealth in ideas ... some of which seemed to give very serious challenge to the foundations of Medieval Christendom. These were, as the church saw it, serious "heresies." Some of these developments became quite bizarre – though honest in their endeavor to aspire to a higher life. For instance, the Albigensians in the south of France were coming together in new communities focused on what were distinctly "Eastern" impulses (or Persian mysticism). The church was ruthless in its suppression of these heretical instincts. But mostly these developments simply produced a demand for Christian instruction, even the privilege of being able to read Christian scripture – such as among the Waldensians. Though it was a very orthodox Christianity that the Waldensians gathered to study, they did so outside of the precincts of the church hierarchy. Thus they too were put under the sword by the Church as "heretics." So the church waged war on these expansive impulses--with the same vigor it pursued the crusades against Islam. In the process of exterminating the Albigensians, they succeeding in the process in crushing the newly blooming flower of Latin culture in Southern France and made very nervous those with any instincts for reforming the church. [The Waldensians took to the mountain fastness of the Alps--and held out there until they became joined to the Protestant movement a few centuries later.] |

|

Humanism Stirs in Northern Europe as Well

Geoffrey

Chaucer (1343-1400)

|

England and France During the Hundred Years' War

(1337 to

1453)

Edward III of England (ruled

from 1327 to 1377)

from the 15th-century Bruges

Garter Book

Richard II (1377) coronation

portrait

London, Westminster

Abbey

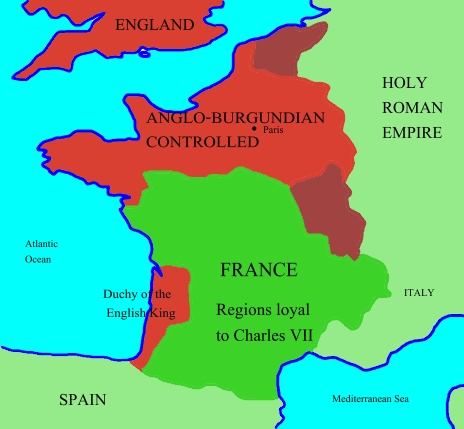

France in 1435 during the

Hundred Years' War

the consequences of the

Battle of Agincourt

(brownish-red are territories

acquired by English King Henry V)

Wikipedia - "France

in the Middle Ages"

The English Siege of Brest

Bodiam Castle, England,

1300s

Claus Sluter – The

Well

of Moses (c.1400)

Dado, Way of the Cross,

cloister, Charterhouse of Champmol, near Dijon

House of Jacques Coeur (financial

adviser to Charles VII) Bourges (1443-1451)

Hôtel-Dieu, Beaune (Côte d'Or, France)

Hospital founded by Nicolas

Rolin, Chancellor of the Duke of Burgundy (c. 1443)

Flanders During the High Middle Ages

Gravensteen Castle in

Ghent ... of the counts of Flanders (c. 1180)

built in great part to keep the independent-minded merchants of Ghent

under some degree of feudal control!

|

|

The "Babylonian Captivity" of the popes

But the all-important church did not keep up with this revival of European vitality. In 1309 the French king more or less forcibly brought the pope to live in Avignon in Southern France under his "protection." (otherwise known as the "Babylonian Captivity"!) This so compromised and enfeebled the papacy that soon other powers were supporting their own candidates to the papacy. Thus as the 1300s rolled along the popes gave more the appearance of being mere pawns in the political struggles of Europe – than they did of grand leaders of Europe's huge religious community. Then when in 1377 the pope was finally returned to Rome, several "popes" competed for recognition. This continued to worsen the spiritual dignity of the papacy, whose image dropped decidedly in the eyes of the faithful – and remained at a low for quite some time. |

The Pope's Palace at Avignon (Southern France)

where they stayed during their "captivity" in the 1300s

|

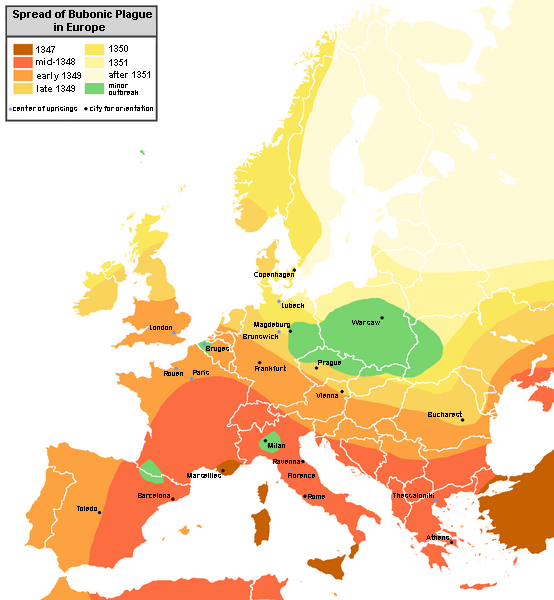

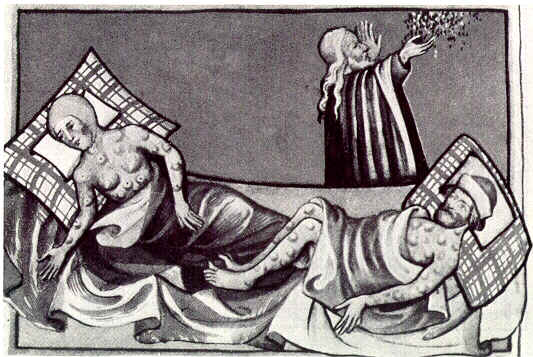

The Black Death (1348-1350)

In the mid 1300s the Black Death (or Bubonic Plague) struck Europe – wiping out 25 million people. In England, in a 3-year period it wiped out half of the population of 4 million people. After this a wave of other epidemics swept a much weakened Europe. Though the human spirit of Europe survived this disaster, the church with its previously unquestioned powers, would lose considerable moral and spiritual respect because of its very visible inability to defend a people crushed by forces they could not comprehend. |

The spread of the Bubonic plague in Europe - mid-1300s

Wikipedia

The "Black Death"

Plague victims blessed by

a priest

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges