|

|

|

|

The Renaissance: A Time of Transition

Though there was no specific event to mark the end of the middle ages and the on-set of the modern era, the 1400s seem to be the all-important transition time. As is typical in human history, this time of great intellectual growth was built solidly on the rapid growth of wealth, fueled by new industrial and commercial technologies. This period of transition into modernity, known today as the "Renaissance," was based heavily in Italy, especially the cities of Venice, Florence, Siena, Mantua, Pisa, Milan, Urbino, Rome and Naples – but was also found in significant portions of Northern (mostly coastal) Europe ... through the natural links that commerce produced and by scholars who studied in Italy and took its learning north. Thus in addition to a number of vibrant Italian cities, the Renaissance also extended to Bordeaux and Paris (France), London and Bristol (England), Bruges and Antwerp (Flanders) and the coastal German cities (such as Lübeck and Hamburg) of the Hanseatic League ... among a number of other European cities. On the face of it, it appears that the Renaissance was essentially an economic affair, a rapid growth of commercial wealth that aided greatly in producing an intellectual revival in the form of a strong interest in pre-Christian Greco-Roman philosophy, in a dazzling flowering of the fine arts (painting, sculpture, architecture) ... dedicated to the glorification of man and his talents (‘humanism’) rather more than God and his traditional role in the Christian world. The Renaissance in part birthed by earlier contact

with the world of Islam during the crusades Plunder of the Muslim Middle East by "crusading" Christian armies from the West no doubt got this growth started – all the way back in the 1100s. But with the revival of Muslim power in the second half of the 1100s and the contraction and then destruction of the Western position in the Middle East during the 1200s this growth might have come to an abrupt halt. However, the Muslims found it profitable to allow Westerners to continue to come as peaceful pilgrims to the Holy Lands of the East – and even to trade with them in Western goods (wood, metals, fish and grains) in exchange for Eastern goods (spices, silks, various fineries). The Muslim traders grew prosperous off this trade. But so did their European counterparts, especially in the commercial cities of Italy (Venice, Florence, Genoa) and Northern Europe (Antwerp, London, Paris, Hamburg). Particularly notable in the development of the new commercial classes was the Medici family of Florence, Italy. The two giants of the family, Cosimo and Lorenzo de Medici, became not only fabulously wealthy, but also major underwriters of the artistic/intellectual development of Renaissance Italy. Technological Development

This commerce in European goods called forth industrial growth – and industrial growth called forth new technologies. The number of inventions from newly emerging European inventive minds was phenomenal. But a few stand out not only because they added so much to industrial development – but because they came to have also such a profound impact on the European mind-set or spirit. The clock, with its carefully interworked systems of gears and wheels, seemed to serve as a symbol of the new sense of order which underpinned the whole universe – an order which existed by its own right. Likewise the compass gave the traveler, especially the new bold class of seafarers, as sense that life had key foundation points – which man of his own could fathom and use for himself. Widespread printing of the Bible

But there is no question that the one technological development that most revolutionized the times was the invention of the printing press. In around 1450 Johannes Gutenberg introduced the new printing process (moveable type) which revolutionized the production of written material – and the process of learning and the status of religion. One of the first impacts of the new printing process was the wide publication of the Vulgate bible, and the appearance of new translations of the Bible into the common languages of the people: German (1446), Italian (1471), Dutch (1477) Spanish (1478--but subsequently suppressed), French (1487), Czech (1488). [Manuscript copies of portions of the Wycliff Bible also were circulated widely – though not in printed form until the Reformation in the next century.] A Shifting Sense of History

All of this had served to produce by the 1400s both a definite continuity with the long development of Western Christian culture and yet at the same time a strong departure from many of the ways the Christian community had understood the cosmos around it. The Christian mind had long (a thousand years) seen the sweep of history in a profoundly dualistic fashion: there were the times before Christ and the times since then. Every thing before that even had meaning for them only as preparation for this grand event. Everything since that event was measured in terms of how it gave fulfillment to God's plan of salvation for human life. Christians traditionally had been certainly mindful of the importance of Rome. It seemed to them to be no mere coincidence that Rome reached its greatness (presumably in the reign of Augustus) at about the time Christ was born. To the Christian mind, this was God's way of preparing the civilized world physically to receive the gospel. They were aware of many of the unique features of Roman thought – but either they dismissed that thought as a carryover from darker days – or as metaphor, pointing to and confirming the gospel message. Thus they read Virgil, Ovid, Cicero, Livy with a profoundly Christian interpretation of the meaning of their works. So also did they understand Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. But by the 1400s, without dismissing their Christian loyalties or pieties, the Renaissance mind was looking back on the days of Greece and Rome through a new set of eyes. There had been growing, since the early 1300s (perhaps even earlier) a fascination with Roman ways in themselves, without having to go through some kind of Christian interpretation. This was timed with the reaction against scholasticism as an arid, intellectually arrogant ambition of the human reason to bring all things under systematic theological mastery. This was timed with a desire to explore more deeply the "humane" features of human life: the simple passions, the loyalties, the love that connected human life with God and Christ – and with the rest of the human community. Things came to be of interest in themselves to the enquiring European mind as it moved through the 1300s and entered the 1400s. They came to be of interest not because they conformed to some great intellectual system but because they gave life to human existence. Thus did they now approach Virgil, Ovid, Cicero, Livy – not to further undergird a well-rehearsed medieval world-view, but to listen to them speak out of their own times, as fellow humans trying to find in life the same deeper qualities of human existence. The Development of the Renaissance Mind

We need to make note at this point that who we are talking about in reality composed only a tiny minority of the people of those days. By and large the mass of the Europeans living in those times probably retained the older medieval world-view. When we are talking about the "Renaissance mind" we are describing a small group of wealthy and powerful businessmen, an equally small number of intellectuals, both secular and religious, and a small, curious group of adventurers. However, though small in number, they were very powerful in terms of shaping the events of their day. In any case, it is to them that we look when we describe the Renaissance mind. Though these individuals remained Christian to the core, they began to take a dimmer view of the way that their faith had been mediated by the Church during a 1000-year "dark ages." They instead sought to validate their Christian faith on the basis of personal loyalties and personal virtue. These people were doers – who used their minds in service to the needs of the family and local community – the "patria" as they understood it. They were not contemplatives; monastic life was not for them a Christian ideal. They were not knights living to honor the code of chivalry; that was much to abstract a notion for them. They were practical, "earthy" in their interests, and sought to use their considerable worldly talents for the common good. This was their understanding of their Christian responsibilities, their accountability before God. In their "earthiness" they were an incredibly curious lot. They of course studied all the classic works they could get their hands on. They already knew Latin; they now took on Greek and even Hebrew. They wanted to go back to the "sources" themselves of the intellectual foundations of their world. They took in the works of the early church fathers – more authoritative for them because they were closer to the original events of Christ. But they also became quite as familiar with the wide range of "pagan" works of Greece and Rome. The idea was that if it came out of that older age, it was truer, purer. Indeed, some of them became literary scholars of the first order – such as Lorenzo Valla, who studied the linguistic structure of the ancients – and was able to demonstrate that the "Donation of Constantine," by which the popes claimed vast temporal powers received from the Emperor Constantine (early 300s), was actually a much later document employing a much later Latin more characteristic of the Middle Ages – when it was probably written! In Princely Politics

This new spirit of Renaissance humanism also captured the hearts and souls of a number of princes or secular-military rulers who developed quite large views of themselves, individuals who were coming alive to the possibility of undergirding and extending their personal political rule through very worldly means, including crude violence if necessary. These new rising leaders varied from feudal kings and even barons and dukes of Northern Europe, to the powerful Medici family (extremely rich banking family of Florence), to the professional soldiers or condottieri such the Sforza family ruling Milan ... who all sought greater independence from the restraints of the Church and Holy Roman Empire in the pursuit of their more local ambitions. European Christendom was clearly fracturing morally and politically, and these princes each wanted their own portions of that dividing Europe. And they were willing to do most anything to acquire those portions. The rather cynical political writer of the late Renaissance, Machiavelli, did not invent this rising mindset – he merely described it and its operation quite accurately in his classic work, The Prince (1513). He would be condemned by later humanists for his less than utopian views on human motivations and behavior. But he was merely an analyst, hoping that the political realism he saw brewing around him could be employed to bring about a united Italy (under a strong-handed Prince) ... in order to ward off Northern European princes (notably the French and Spanish kings) who viewed the disunited Italian peninsula as a place where they might pick up more territory in their personal rise to power. The rising power of the European city

All of this wealth in trade flowing to the rising European cities would have the same political effect that the breakup of Christendom did for the rising princes. But in general the merchant cities of Europe went at the matter of acquiring new powers differently than did the princes. Like the richest of all of them, the Republic of Venice, urban politics tended to be corporate, drawing into the position of leadership a wider circle of local interests than the single-individual dominated kingdoms and principalities. Most cities were run or managed by a corporate council ... led by individuals elected to office by committees or guilds of tradesmen and manufacturers. Urbanites were also a different breed of Europeans. Their business world required the ability to read, write and perform complicated mathematical processes (at a time when the rural feudal princes of the vast European countryside were often illiterate, reading and writing not being a very important factor in their rule). Their urban world was also larger than the traditional world of rural feudal Europe. Travel and business connections abroad – not to mention the ability to read and write – gave them a much bigger understanding of how the world works. Europe’s urbanites were an independent-minded lot, adventurers and risk takers, and always a potential challenge to the medieval ways of rural feudal Europe. But they were tolerated, even encouraged, by local princes in whose territory these cities found themselves located. They were after all a source of mobile or moneyed wealth ... increasingly more important to local princes and their ambitions than the feudal vassals who were supposed to offer full support at the princes’ command ... but who proved most unreliable in times of real need. So the princes “chartered” the cities ... contracting with them to receive tax monies in exchange for the prince’s support of their rather independent ways that the cities required in order to do business successfully. Once a prince or king granted a city its charter, it had full rights to operate as it saw fit. Needless to say, cities guarded jealously those chartered rights. But also kings tended to respect carefully those rights ... because they depended so much on their cities’ financial support. In the Church

Certainly the Church also chose to join the gathering economic and political action set loose by the Renaissance. After all, since the fall of Rome it had always been a dominant hand – if not even the dominant hand – in European society. Certainly there were those who objected to the Church taking up such worldly interests. But by and large the view of the Church – notably of its popes, who during the 1400s could be very worldly fellows – was that intellectual revolution, economic gain, and political intrigue were things to be pursued. Thus the church was as active a player in the Renaissance game as the new set of rising secular princes and the urban burgers or bourgeoisie. |

|

A view of Venice

Scala - Florence

Members of the Vendramin Family Venerating a Relic of the True Cross

Accademia of Venice

The Venetian Doge (1501-1521)

Leonardo Loredan - by Belinni

National Gallery - London

Doges' Palace, Venice (1330s

and 1400s)

facade on the jetty, 1300s;

balcony 1404; facade on the Piazzetta, 1424-1442

Canaletto - The Doge's Palace – Venice (ca. 1730)

The Royal Collection - Windsor Castle

Canaletto - The Rialto Bridge from the South

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica

Canaletto - The Campo di Rialto – Venice ca. 1730)

|

The "Carta della Catena": a 15th century view of Florence (c. 1490)

Florence, Museo de Firenze Com'era

Florence's

Duomo or cathedral: The Santa Maria del Fiore – with Giotto's campanile

or bell tower (1330s) and Brunelleschi's dome or cupola (1430s and 1440s)

The "Gates of Paradise" ... doors to the cathedral's baptistry - by Lorenzo Ghiberti (early 1400s)

The interior of the Santa Maria del Fiore

Filippo Brunelleschi's Santo Spirito – Florence (1430s)

Interior of the Santo Spirito

The Medicis of Florence

Cosimo de' Medici (the Elder: 1389-1464) - by Jacopo Pontormo

Founder of the Medici dynasty

Uffizi Gallery

Lorenzo de' Medici (1449-1492) – bust

by Andrea del Verrocchio

(1480)

Also known as Lorenzo the Magnificent ...

elevating the family dynasty to true greatness (grandson of Cosimo)

Samuel Kress Collection,

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The Palazzo Medici

Giuliano da San Gallo – Villa

Poggio, Caiano, Tuscany

constructed for Lorenzo

de' Medici, 1480-1485

The Life of the Florentine Upper Bourgeoisie: The Davanzati family palace

The Palazzo Davanzati – a typical home of the Florentine elite

The Palazzo Davanzati – entry hall

The Palazzo Davanzati – staircase in the inner court

The Palazzo Davanzati – the

second floor grand salon (overlooking the street)

The Palazzo Davanzati – the Room of the Parrots

The Palazzo Davanzati – the

upper-floor kitchen

(located there to keep smoke

and odors out of the house)

The Palazzo Davanzati – one of the bedrooms at the rear of the house

The Palazzo Davanzati – another bedroom

Scholarly-intellectual ferment in Florence during the Renaissance

Four prominent members of

the Platonic Academy in Florence – by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1486-1490)

Marsilio Ficino (translated

Plato's works into Latin);

Cristoforo Landino (student of Aristotle, Petrarch

and Dante);

Angelo Poliziano (poet, dramatist and tutor to Lorenzo de Medici's

children)

and Demetrios Chalkokondyles (taught Greek in Florence)

Santa Maria Novella, Cappella Tornabuoni, Florence

Florentine politics

Florentines routing the Sienese

at the Battle of San Romano – 1432 (by Paolo Uccello – c. 1438-1440)

National Gallery, London

Charles VIII and his French

troops enter Florence – November 17, 1494 – by Francesco Granacci

Ufizzi, Florence

|

The Sforzas of Milan

Francesco Sforza – Duke of

Milan / Bianca (Visconti) Sforza

– his wife

Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

Ludovico Sforza and his wife

Beatrice – before the Virgin Mary and Christ Child

Ludovico was a major patron of Leonardo da Vinci, Bramante and other artists;

unfortunately he was not as wise politically as he was artistically, inviting the French

into Italy

– only to be undone by them later

Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

The Gonzagas of Mantua

Andrea Mantegna's painting

of the family of Ludovico III Gonzaga, marquess of Mantua

Mantua, Ducal Palace

The Montefeltros of Urbino

Frederico da Montefeltro,

Duke of Urbino – and his son, Guidobaldo (c. 1475)

Urbino, Galleria Nationale della Marche

Franciscan monk and mathematician

Luca Pacioli - by Jacopo de' Barbari

(with patron and student

Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino)

Naples, Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte

The Strotzis of Naples (and Florence)

Merchant-banker Filippo Strozzi

He developed a financial empire in Naples after the Medici drove the

Strozzi family

out of Florence in 1434

Paris, Musée du Louvre

|

| The

church was finding itself hard-pressed to maintain its traditional

place of authority within the European cultural sphere. It tried to

resist its loss of status – but found that circumstances were making it

increasingly difficult to hold its own. For instance, the translation of the Bible from Latin into the languages of the people gave them the power to discern for themselves the word of God. Through the rapid growth of literacy that accompanied the growth in Bible and other book publication this development became quite extensive. Thus the church became very alarmed by the publication of the Bible – more alarmed that it was over the publication of pagan Roman and Greek literature – protesting that this wide dissemination of the Bible would cause the emergence of wrong interpretations and subsequently the spread of new heresies. The church well understood that it was thus rapidly losing its monopoly on learning and authoritative knowledge. Also, with the rise of the secular, humanist spirit, especially in Italy, religion was becoming seen more and more as a matter of internal religious disposition of the individual, and less and less as a matter of the sacraments, teachings and traditions dispensed by the church. Yet interestingly, many of the church leaders themselves chose to join in with the spirit of the times. Certainly there were those clergy who objected. But by and large the view of the church – notably of its popes, who during the 1400s could be very worldly fellows – was that this intellectual revolution was something to be pursued. Thus the church was as active a sponsor in this matter. Indeed, the worldliness of the church was becoming a well-recognized feature. The Roman hierarchy was viewed widely as being venal and corrupt – as secular politics rather than spirituality preoccupied the popes of the 1400s. The dreams and schemes of the Roman church became more grandiose, overstepping even the wealth of Italy, and beginning to drain the wealth of the church north of the Alps. And the personal conduct within the highest offices of the church, including the papacy itself, was at times scandalous. Discontent against the Roman church thus began to spread in the North of Europe by the end of the 1400s. Led especially by a number of northern humanists, many Europeans began to demand reform the church, not only in its ethical behavior but also in its very lines and features as an institution. Reform-minded individuals were beginning to demand that the church should drop its medieval trappings and purify itself along the lines of the early church described in scripture. |

The Notorious Borgias (originally Spanish)

Rodrigo Borgia, Pope Alexander

VI (1492-1503)

Appartamento Borgia, Vatican

City

Caesar Borgia – son of Pope

Alexander VI

(the inspiration for Machiavelli's

Prince)

Bergamo, Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti

Lucrezia Borgia – daughter

of Alexander VI and sister of Caesar Borgia

Portrayed as St. Catherine of Alexandria - by Pinturicchio

Sala del Santi - Appartamento Borgia, Vatican

City

|

One

of the key expression of this mood was contained in the writings of

Machiavelli, who pleaded for some kind of political authority to step

forward and, by whatever means possible (even treachery), give

political expression to this nationalist urge – in Machiavelli's case,

an Italian urge. But Italy was the one geographical area that

would be refused such a development. The political interests were

too varied and oppositional and the interests of powerful outsiders

were lined up against the development of a true Italian national

political unit. Not for several more centuries would Italy see

its nationalist hope finally come true. One

of the key expression of this mood was contained in the writings of

Machiavelli, who pleaded for some kind of political authority to step

forward and, by whatever means possible (even treachery), give

political expression to this nationalist urge – in Machiavelli's case,

an Italian urge. But Italy was the one geographical area that

would be refused such a development. The political interests were

too varied and oppositional and the interests of powerful outsiders

were lined up against the development of a true Italian national

political unit. Not for several more centuries would Italy see

its nationalist hope finally come true. |

Young Niccolo Machiavelli - by Santi di Tito

Florence, Palazzo Vecchio

Machiavelli's study at his

country villa at Percussina where he penned The Prince

House of Machiavelli, Percussina,

Italy

|

|

Reaching Beyond Christianity

During the 1400s the intellectual ferment in the West--especially in Italy--became profound. But this ferment was no longer limited to theology and matters of religious interest. It included a huge curiosity about the human spirit--here and now--and the natural human habitat which surrounded it. Interestingly, the renaissance involved a Platonist revival as a reaction to (Aristotelian) scholasticism. By the end of the 1300s the study of Plato was undergoing a revival. But this Plato was not the traditional variety, distilled and transmitted through ancient Christian commentary. It was the full and direct Greek variety – inspired by new Greek translations which made Plato's original works directly accessible. In Plato they discovered the love of beauty, even the concept of the erotic, as a virtue alongside ethics and logic. In keeping with this new spirit, the Academy of Florence was founded in the second half of the 1400s by the financial support of Cosimo de Medici. It involved a very distinct Neo-Platonist departure from the scholastic universities. But this new learning did not stop at the boundaries of classic Western thought. Even ancient (often non-Western) philosophy, religion and mysticism began to come under study: ancient Egyptian and Babylonian religions, Persian Zoroastrianism, Pythagorean mysticism, the mysticism of the Jewish Cabala. Even pagan astrology (which had never been far below the surface of Medieval thought) was openly revived – along with interest in the Greek and Roman pagan deities. All of these were approached in the spirit of discovery of a God operating on a more universal plane than the limited field of traditional Christian thought. Pantheism, even polytheism, was spreading rapidly. Italian Humanism

At the same time that the field of inquiry was expanding outward into the world, it was expanding inward into the private human soul – especially in Italy, which took the lead in the development of this mood in the early 1400s. The human soul was seen as reflective of the grandeur of a cosmic God – mirroring God's nature and intelligence. Man was endowed with power to bring to actuality the perfection of the divine Forms of Plato. The doctrine of original sin was quietly being put aside. Northern European Humanism

In the latter half of the 1400s and into the 1500s, humanism spread to the intelligentsia north of the Alps, although there it remained a Christian humanism. Medieval scholasticism was put aside and focus was turned to the powers of the individual to know God through a private spiritual life, and through study of the original Greek and Hebrew Scriptures and the writings of the early Church Fathers. Germany, France, England and Belgium produced their own humanist geniuses: Reuchlin, Lefevre, More and Erasmus, respectively.

More

Erasmus

The Artistic Expression of This New Spirit

In keeping with the spirit of the times, art reached beyond traditional religious themes to reflect this interest in the individual--and the passions of the living person. The human figure was represented with physical accuracy, complete with deep human expression – rather than in accordance with to traditional formulas of religious iconography. Portrait painting and sculpture of the wealthy and powerful became common. Paintings of the common life of the European townsmen and peasants also began to proliferate. And of course the fascination with the pre-Christian world of pagan Greece and Rome received artistic attention. Architecture was called upon not only to build churches, but also trade halls and private homes. Poetry was now reaching well beyond religious themes into the areas of human love and passion. Spirits were freeing up and searching ever more widely for objects of artistic interest. The names of the artists who stood behind such new ways are almost innumerable. But certainly Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Pieter Bruegel stand out as giants of their times.

Da

Vinci

Michelangelo

Brueghel

On-Going Mysticism

Nonetheless, the medieval instincts for the mystical outlook on life did not simply die away because of the changes in the human spirit of Renaissance Europe. In many cases these changes produced even a greater determination among some to hold to the older mystical view of life as an act of spiritual defiance. For instance, the book of Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, was – next to the Bible – the most widely read book of the times. It was hardly a secular work ... but spoke to the quite strong spiritual hunger still present among the people of that time. |

The Human Realism in the Arts reveals the spirit of the times

Donatello – St. George

(1415-1417) marble

Florence, Museo Nazionale

del Bargello

Tomasso Masaccio's Holy Trinity

– 1425

Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Fra Angelico – The Annunciation

(1440-1441) fresco

Florence, Museo di San Marco

Fra Filippo Lippi – Madonna

and Child (1452) Oil on panel

Florence, Palazzo Pitti

Ghirlandaio - The birth of the Virgin (c. 1485)

Florence, Cappella Tonabuoni, Santa Maria Novella

Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli – Spring

(c. 1470) tempera on panel

Florence, Galleria degli

Uffizi

Sandro Botticelli –

Primavera

(detail)

Botticelli's Birth of

Venus – ca. 1482

Scala, Florence

The Florentine feminine ideal

(Simonetta Vespucci?) – by Sandro Botticelli

Städelsches Kunstinstut,

Frankfurt

Giovanni Bellini – Virgin

and Child (c. 1487) oil on panel

Bergamo, Accademia Carrara

Equestrian statue of the condottiere Bartolommeo Colleoni

designed by Verocchio 1481-1486; cast by Alexandro Leopardi (ca. 1490-1495)

Venice, Campo di SS. Giovanni e Paolo

Raphael Sanzio

Raphael Sanzio – Portrait

of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni (1505-1506) oil on panel

Florence, Palazzo Pitti

Raphael Sanzio – Madonna of the Meadow (1506) oil on panel

Raphael Sanzio – The School

of Athens (1511-12) oil on panel

Vatican City, Apostolic

Palace

Raphael Sanzio – Baldasare

Castiglione (1514-15) oil on panel

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Leonardo da Vinci's self-portraits – younger and older

Leonardo da Vinci's Last

Supper

Fresco on the walls of the refrectory of Santa Maria delle

Grazie, Milan (prior to restoration)

Leonardo da Vinci's Last

Supper - restored

Da Vinci's Mona Lisa

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Vitruvian Man (c. 1485)

Venice, Accademia

From Leonardo da Vinci's

studies of flowers

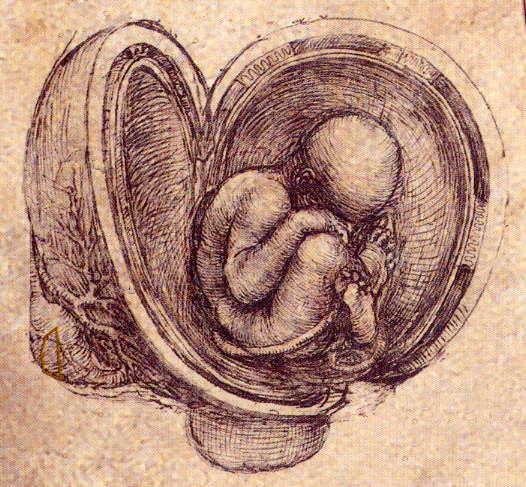

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a fetus in utero (1510)

Venice, Galleria dell'Academia

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of an assault vehicle

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a life preserver

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana

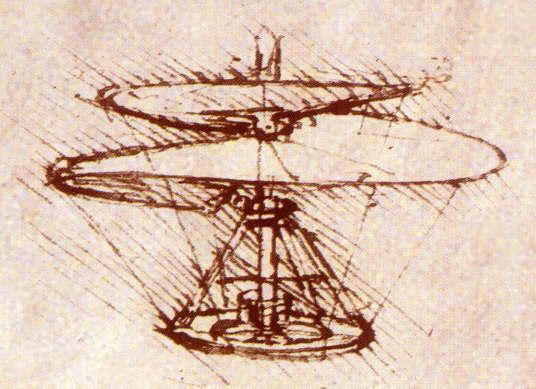

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a type of helicopter

Giraudon, Paris

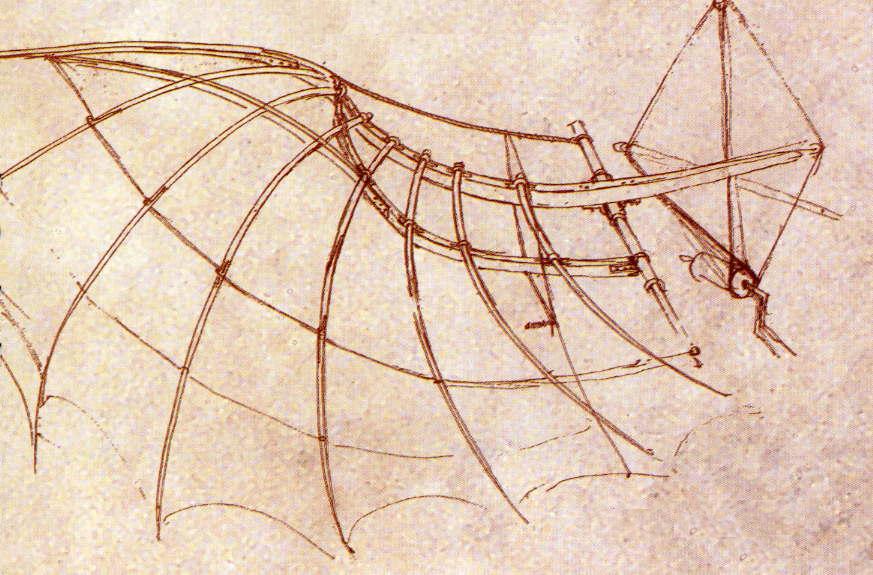

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a mechanical hand-cranked wing

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana

The brilliant sculptor: Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo's

Pieta

Michelangelo Buonarroti

– David (1501-1504) marble

from the Palazzo Vecchio,

Galleria dell'Accademia

The Vatican's renovated St. Peter's Cathedral in Rome

Michelangelo, Bramante and

Raphael meet with Pope Julius II

(by 18th century artist

Horace Vernet)

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Michelangelo presents Pope

Paul IV his model of the St. Paul's Cathedral

(by Domenico Cresti da Passignano)

Saint Peter's Cathedral at the Vatican, Rome

Interior of St. Peter's Cathedral

The Sistine Chapel

Vatican, Rome

The ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel – completed by Michelangelo in 1512

Vatican, Rome

The Delphic Sybil – detail

from the Sistine chapel ceiling

Vatican, Rome

Palladio - the Romanesque architect

Andrea Palladio's Villa

Rotonda (near Vicenza)

|

FRANCE

The Limbourg Brothers (Jean and ) late 1300s and early 1400s

Jean de Limbourg – Les Très

Riches Heures du duc de Berry – October (1413 - 1416)

Chantilly, Musée Condé

Enguerrand Quarton – The

Villeneuve-les-Avignon Pieta (c. 1455) oil on panel

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Jean Fouquet – Virgin

and Child surreounded by Angels (after 1452) tempera on panel

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum

voor Schone Kunsten

Jan Van Eyck (1390 - 1441)

Jan Van Eyck – The Marriage

of Giovanni Arnolfini and Giovanna Cerami (1434)

London, National Gallery

Rogier Van der Weyden (1399/1400 - 1464)

Rogier Van der Weyden – The

Descent from the Cross (c. 1435) oil on panel

Madrid, Museo del Prado

Konrad Witz – The Miraculous

Draught of Fishes (1444) oil on panel

Geneva, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire

Stefan Lochner – The Virgin

of the Rose Bush (c. 1440) oil on panel

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz

Museum

|

FRANCE

Tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal

of Burgundy (c. 1480)

From the abbey church of

Citeaux

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Great Stairway of the François I wing, Chateau de Blois (1515-1524)

The Chateau de Fontainebleau – expanded greatly by King Francis I in the 1520s and 1530s

Hugo van der Goes (1440 - 1482)

Hugo van der Goes – The Portinari Tryptich (c. 1475)

Florence, Galleria degli

Uffizi

Hans Memling (c. 1440 - 1494)

Hans Memling – Triptych

of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist

(c. 1474-1479)

oil on panel

Bruges, Hôpital Saint-Jean

Hieronymus Bosch (145 - 1516)

Hieronymus Bosch – The

Haywain (1500-1502) central panel of a triptych; oil on panel

Madrid, Museo del Prado

Quentin Metsys (c. 1465 - 1530)

Quentin Metsys – Money Changer

and His Wife (1514) Oil on panel

Paris, Musée du Louvre

GERMANY

Albrecht Dürer (1471 - 1528)

Albrecht Dürer –

Self-portrait

(1493) parchment glued on canvas

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Paumgartner Alterpiece (1498-1504) with St. George (left) and St. Eustace (right)

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472 - 1553)

Lucas Cranach the Elder – Portrait of Johann the Steadfast (1509)

London, National Gallery

Matthias Grünewald (c. 1475 - c.1528)

Matthias Grünewald – The

Crucifixion (1512-1516) central panel of the reredos,

Monastery of the Antonites,

Issenheim (Upper Rhine) oil on panel

Colmar, Museum Unter den

Linden

Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497 - 1543)

Holbein – Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (1527-8)

|

| This

spirit of Renaissance earthiness revealed itself importantly in

another, closely related, way. This was the "Age of Exploration"

– a term we use in reference to the beginning of the exploration

of the Seas and continents around Europe by a wide variety of

Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish explorers – professional

adventurers really. They were sponsored and funded by rising

European princes who were looking for ways to gain greater access to

the wealth of the East. These rising merchant princes also put

forth the idea that they were also greatly interested in

spreading the Christian domain to as much of the world as they

could. Thus it was that as the Renaissance gathered speed, the

race was on among princes and their commissioned explorers to see who

could achieve the greatest portion of this quasi-Christian,

quasi-commercial glory The first prince to get a jump on the race (in the early-mid 1400s) was Prince Henry of Portugal. He sent out numbers of Portuguese sailors to explore the African coast in search of a southern route around the southern tip of Africa (1488) in order to secure the wealth of the East in trade ... and souls of the East in Christian conversion. Soon the Spanish joined the race. A few years later the Italian explorer Columbus, in service to the Spanish, sailed across the Atlantic, to arrive at the West "Indies"--not even realizing the importance of his feat: he had reached islands just offshore from a hitherto unknown continental land mass, America. In 1520 the Portuguese nobleman turned Spaniard, Magellan, sailed his Spanish fleet around the southern tip of South America and headed west across the Pacific (himself dying along the way), with one of his ships arriving back to Seville Spain in 1522--having made the first complete circumnavigation of the world. Soon the French, the Dutch and eventually the English would join the race. Thus during the rest of the 1500s the seas were full of the exploits of numerous explorers – heading in every direction to lay claim to the riches in material wealth and human souls of the ‘East.’ |

Christopher Columbus – by Sebastiano del Piombo

Library of Congress

Vasco da Gama

Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga

Ferdinand Magellan – a Portuguese captain sailing for the Spanish king Charles V

(He

did not personally complete the global circumnavigation – for he was

killed in a confrontation

with natives in the Philippines. Only one ship of his fleet made the full voyage)

Newport News, VA - The Mariner's Museum Collection

Portuguese slave trading

colony at Elmina (founded 1421) on the Gold Coast (modern Ghana)

Library of Congress

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges