|

|

|

|

The Protestant Reformation

Religious purists in the agrarian hinterland of the West objected strongly to the new secular or materialist spirit growing up with the Renaissance. One of these was the German professor-priest Martin Luther who in 1517 issued a challenge the church over this new interest in worldly affairs. He wanted the church to return to the pure (spiritual) ways of the early church – and back away from all this recent interest in power and wealth – which was rapidly corrupting it. Also, he wanted faith initiatives to be returned to the individual believer. Priesthood belonged to the believer – not to the religious hierarchy. To press home this challenge, Luther translated the Bible into German – to give the common people access to all priestly authority: the Word of God. Irritated, the church told him to cease his challenge. But he refused to yield. When princely political interests came to his aid--his rebellion exploded. The "Lutheran" movement began spreading across the north of Germany. It would soon overtake Scandinavia. Medieval Europe, or what was left of it, began rapidly to fall into a state of civil war.

|

|

|

John Wycliffe (1320-1384)

At Oxford university, John Wycliffe by 1370 stirred up controversy in teaching the freedom of religious conscience of the individual believer, who stood in faith directly before God. He attacked a multitude of practices and features of the church – especially its wealth. Wycliffe's followers, contemptuously called "Lollards," from a Dutch word of derision meaning "mumblers" (originally directed at the Beguines), preached reform in England. Also, Wycliffe's movement made much of the Bible available to the masses in its English translation from the Vulgate. Wycliffe's Lollard movement was eventually suppressed – but so was the intellectual ferment of Oxford university where his teachings had been widely accepted.

John Wycliffe's portrait

in Bale's Scriptor Majoris Britanniae - 1548

John Wycliffe in his

study

Burning Wycliffe's bones,

from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563) The Reform Councils and the Council of Pisa (1409)

The institutional church was trying to unify and reform itself--and at the same time bring independent voices of reform under submission – through the conciliar movement, a series of church councils called to unify the papacy and reform the church. The Council of Pisa, in order to end the embarrassment of having two contending popes claiming to be the sole head of the Catholic church, deposed the two contenders, Gregory XII and Benedict XIII. This reform was undertaken even by the cardinals of both popes--who elected a new pope, Alexander V. But when the two popes refused to step down, there were then three contending popes! John Hus (1374-1415)

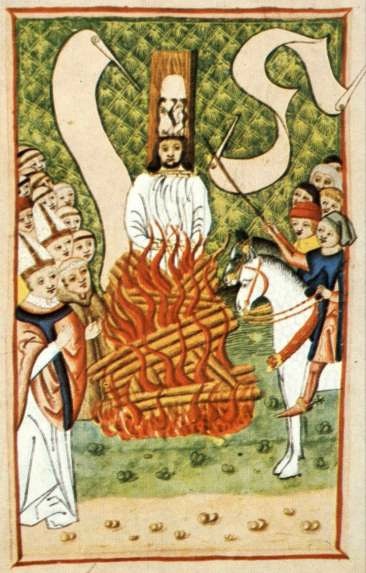

Wycliff's teachings reached Bohemia after his death and were picked up by John Hus, at the University of Prague, in the early 1400s. Hus translated Wycliff's works into Czech and gave life to the reform ideals to the people. This stirred fear in the hearts of church officialdom. In 1414 Hus was called (under the Emperor's promise of safe conduct) to the Council of Constance to explain himself. But he was arrested by the Council and burned at the stake in 1415 – sparking revolt in Bohemia. Attempts to put down what had become a popular national revolt failed; finally a compromise was reached with the Hussites. |

Huss presenting his case at the Council of Constance

Huss being prepared for his death

Jan Hus burned at the stake

- 1415

Jan Hus burned at the stake

|

The Council of Basel (1431-1449)

The council initially made progress toward reconciliation with the Hussites. It defied a papal order to move to Bologna, claiming superior authority to that of the pope (Eugenius IV: 1431-1447). But its subsequent efforts at reform of the ecclesiastical hierarchy caused it to overstep its true power – and Eugenius used this to his own advantage. Also, the pressing problems of the Turks and the need for closer relations with the Eastern church, provided the occasion for the pope to split the council's power bringing a portion of the council to Ferrara while the remainder carried on in Basel. Its decision in 1439 to elect a pope in opposition to Eugenius undermined most of the council's residual authority. In the meanwhile, the papacy in Rome emerged as an ever-stricter defender of its ecclesiastical authority. Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498)

Florentine religious reformer

Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola –

His prophecies about a new age arising out of corruptions of the former age seemed validated when the French king invaded Italy and the Medici fled Florence, allowing Savonarola to establish something of a puritanical Republic in Florence in taking on a grand effort to clean up the morals of Florentine society and open Florentine government more widely to the people themselves.. But his refusal to join Pope Alexander VI's Holy League (against the French) brought him deep trouble with the church hierarchy (the pope threatened to put all of Florence under a papal interdict) ... and gave a local religious rival the opportunity to challenge Savonarola's religious authority. In 1498, the Pope and his agents challenged Savonarola to a public test by fire – which Savonarola failed miserably. He thus confessed (under torture) to fraud, he lost his popular support at home, and he and two of his supporters were arrested, hanged and their bodies burned in Florence's public square. Again, this was supposed to provide an object lesson for those inclined to challenge the religious-political status quo of old Christendom. Nonetheless, much of his reform movement lived on in Florence among other followers. However, in 1512, the Medici – with papal support – were able to return to power in Florence ... and end the reform movement there. |

The death of Savonarola (and followers) in Florence's central plaza - 1498

|

|

A Sense of Growing Decadence in the Church

The profound corruption of the church – from popes down to parish priests – was a source of major frustration to the faithful--who had a profound sense of God's judgment over His people, the Christian community. Judgment would fall on this New Israel as surely as it did the Old Israel. A Growth of Independent Personal Judgment

Combined with this sense of frustration with the church was a growing independent-mindedness on the part of a new humanist intelligentsia. The church no longer held a monopoly over the thinking of scholars and teachers. The new printing presses had put in their hands a wider range of reading that had ever been available previously. Some of it was pagan, most of it was Christian. But in any case it opened up a world that was not automatically sifted through the scrutiny of the religious hierarchy. Oddly, one of the most unsettling elements of this new literature were the Hebrew and Greek manuscripts of the Old and New Testaments that became widely available. The new Biblical scholarship that this engendered not only pointed out (minor) flaws in the Latin Vulgate – but gave the new scholars a sense of personal judgment superior to that of the official church. The age of the individual conscience was being born! The church could no longer expect automatically to command the thinking of its Christian subjects. Within the context of this independent and very critical mood – at least on the part of a new breed of humanist scholars – "business-as-usual" on the part of the church was bound to create a massive reaction. A Major Shift in the Traditional Political Order of Medieval Christendom

For centuries, the whole of the medieval Christian order had been a single piece – understood to be ordained and supported by the will of God. It was the widely understood principle that all the social orders, from kings and popes down to the vast multitudes of peasants, all had their respective "place" in that medieval political, economic, social, cultural, religious, spiritual order – such places determined by God's natural ordering of all people. A person was placed into that order by the logic of his or her birth – and that by the will of God. It was God that determined who would be born a king, who would be born a peasant. This being God's righteous decree, there was little further thought that could be given to a rearranging this larger medieval social or political order. True, kings and bishops, who both belonged to the upper aristocratic orders, had been battling among themselves since the 1100s for dominance over this larger medieval social order. But such disputes did not involve the masses of European peasant farmers. They simply awaited the outcome of such struggles to see how marriages, political alliances, wars would move them from the domain of one lord (priestly or princely) to another. They themselves had no say in such matters. Their job was to till the soil and pay the lord their feudal dues. They always prayed that God would set over them a fair or just lord. But they themselves had no voice in the matter of who ruled over the land that they worked with their labors. The Rising Urban Power Base of the Renaissance

However the rise during the 1300s and 1400s of European commercial wealth--in competition with the traditional wealth of rural landholdings--was bound to upset this arrangement. Bankers, merchants, industrialists – who congregated along key trade centers – did not fit easily into this older social order. Though certainly their guilds and unions attempted to formalize their wealth, in fact their wealth was dynamic and always subject to a rapid shift in fortunes. The success of their labors was related to the wisdom of investment decisions that they made. To prosper, they needed a free hand – and a mind open to new and ever changing opportunities. During the 1400s this group sat uneasily under the traditional rule of medieval church and crown. Medieval feudal dues in the form of agricultural and military service owed the lord were cumbersome and at times counterproductive to the larger success of this new urban entrepreneurial class. It was inevitable that these towns would become centers of resistance against the medieval land-based social system. Indeed, in case after case these rising towns and cities were able to receive from the traditional local princely or priestly lord new charters which granted them (that is, the commercial elite or oligarchy that ran these towns) a tremendous degree of self-goverment – in exchange for the payment of taxes in currency. This was because money was becoming more important than land in undergirding the military might of a local ruler – and the princely and priestly rulers in fact preferred monetary payments over land service from their vassals. While land assessments and service obligations might feed their courts and fill their armies with men-at-arms – only money could buy them the new luxuries – and the new military technologies – that traditional land-based service could not. Reconstructing a Moral-Legal Order around This Newly Rising Order

But the independence of these towns – in keeping with their real power – did not provide the air of legitimacy that they needed to feel secure in their liberties within the newly rising order. At any time these urban charters might be revoked by the local prince or bishop by any whim or fancy (or suspicion). There really was no "right" of their own that the towns could hold up to these lords in order to demand equitable treatment. At least not until the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s gave them the sense that they had the right to accept or reject political authority in accordance with what their own consciences dictated. There was no power on earth, only God alone, who had the right to judge them in the matters of conscience, even political conscience. |

|

|

Martin Luther's 95 Theses

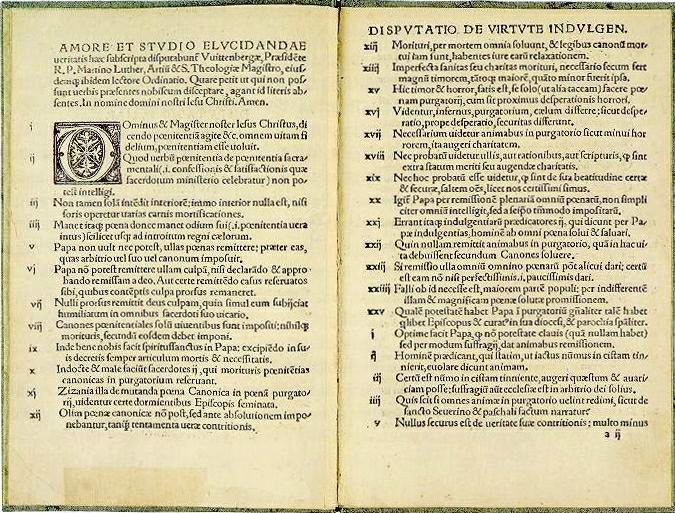

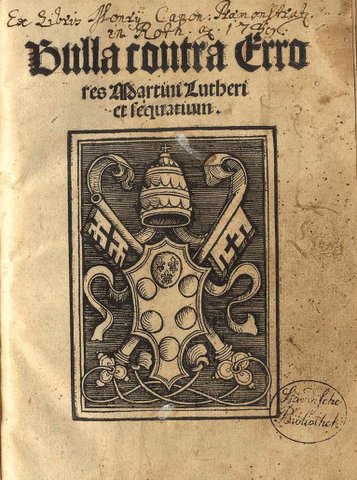

The explosion finally came around the matter of the financing of the lavish building program of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. As an untended spokesman for this critical mindset, in 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the door of the Wittenburg castle church protesting, for theological reasons, the sale of indulgences to finance the pope's schemes. Behind this defiant action was a long personal pilgrimage of Luther, one based on an deep desire to unburden himself of a profound sense of guilt and personal condemnation before God's judgment. For Luther, a personal breakthrough occurred as the message sank into the head of this Augustinian professor concerning Paul's teaching (Galatians and Romans) about divine Grace and forgiveness received through the simple faith of the believer – and not through the demands of any religious law or requirements of a religious system. So "liberated" was he that he felt that his discovery had to be brought to the world. The occasion of the sale of indulgences brought this desire to the fore. With this action of challenging papal authority, Luther, unaware of where this would eventually take him, uncorked an explosive force among fiercely faithful Christians. It also excited the political interests of the German princes who saw in this theological revolution an economic/political opportunity they could not pass up. For Luther the reform movement was related to the matter of a sinner's personal justification before God. Luther showed little interest in making broader changes within Christianity beyond the throwing off of Roman spiritual authority – with its traditions of works-righteousness. Substantial changes in worship, for instance, were of lesser interest to Luther. Also the episcopal form of church government (rule by bishops) was kept by Luther – though with the understanding that the bishops were answerable to the local princes – not to Rome. The pope's ability to reply to Luther's challenge to ecclesiastical authority was greatly limited by the protection that Frederick, imperial elector, placed around Luther. Meanwhile, in Luther's debates with the papal opponents sent to silence him, he was gradually drawn more deeply into a position defiant of Rome. By 1520, Luther's defiance of Rome was total. To Luther, Rome was the anti-Christ. At the end of that year Luther boldly and publicly burned the papal bull requiring his submission. Luther, and much of Germany with him, was in full religious rebellion against Rome. |

Martin Luther - Lucas Cranach

the Elder (1529)

Hessisches Landesmuseum

Darmstadt

"A Question to a Mintmaker"

(the sale of indulgences) - Jörg Breu the Elder (c. 1530)

Disputatio pro declaratione

virtutis indulgentiarum (a printed copy of Luther's 95 Theses)

- Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter

d.J., 1522

Detail of Portrait of

Pope Leo X and his cousins - by Rafael Sanzio (1518-1519)

Florence, Uffizi Gallery

Title page of Pope Leo X's

Bull, Exurge Domine, threatening to excommunicate Martin Luther (1520)

Concordia Theological

Seminary

Wartburg Castle in Eisenach

-

where Frederick III, Elector

of Saxony, hid Luther away (1521-1522) in order to keep him

from falling

into papal or imperial hands

Robert Scarth -

photagrapher

Luther's 1534

Bible

Luther's "Ein Feste Burg"

("A Mighty Fortress")

One of only very few early

printings of Luther's hymn. There are no known first edition printings

left.

This book is a second edition,

and extremely rare. It is in the holdings of the Lutherhaus museum

in Wittenberg,

Germany

|

Emperor Charles V Fights Back

The newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (ruler of: powerful Spain and its wealthy American colonies, the commercially energetic Netherlands, and Austria and much of Italy), now took up the issue on the side of the Roman church. Luther, now excommunicated but still under the protection of Frederick and widely popular in Germany, was called by the Emperor to an Imperial Council at Worms to give account of his views. Here Luther stood firm in his views against the Roman church. Under an Imperial guarantee of his freedom, Luther was able to get away from the Council before the guarantee was retracted. From then on for the rest of his life, Luther remained in seculsion – publishing works against the papacy and bringing forth his German translation of the Bible. In the meanwhile the Emperor found himself preoccupied by an on-going war with France over control of various cities and principalities in Italy. Thus the Emperor was seriously distracted in his effort to quiet Luther. Then the Turkish threat to the Emperor's Austrian holdings rose up again. Luther was relatively safe. |

Charles of Habsburg - Holy

Roman Emperor (Charles V) and King of Spain (Charles I)

by Rubens (but a copy of

an original by Titian)

|

The Tragic Peasant War

Meanwhile the spiritual rebellion of Luther against Rome soon spread as a mood of political rebellion of the German commoner against princely authority. The autonomy of the individual religious conscience gave over easily to the idea of the autonomy of the individual political conscience. But in this, Luther proved to be no rebel. In fact, he stood strongly on the side of the princes against the German rebels (M?ntzer and the "Zwickau prophets") who took up the political cause of the German commoner against their rulers. In the peasant rebellion of 1524-1525, Luther came down harshly against the peasants. The peasants and their leaders were put down cruelly by the local princes and their mercenary troops (6,000 peasants lost their lives alone in the one-day battle of Frankenhausen). The result of the Peasant War was to move real power over to the various German princes. Thus in Germany, the rule of the church was not a matter either of local congregational power – nor of the power of popes and bishops. Rather, it was the ruling prince in each of the many principalities that made up Germany who determined each in his own territory its particular Christian character. Some remained loyal to Rome (the southern German princes), some followed the Lutheran line (the northern German princes). But in any case it was the local princes who made that determination. The dependence of church on state was thus set as the characteristic feature of German Christianity – a feature lasting down into the 20th century. Furthermore, because of Luther's deep conservatism and the limitation of his vision of reform solely to the context of an ongoing, though theologically reformed, agrarian medieval religious order, Luther's movement remained confined to a highly rural, still medieval north-central Europe – and had almost no impact in any of the rapidly developing European urban areas. |

Thomas Müntzer - Leader

of the Peasant Rebellion

An 18th century engraving

by C. Van Sichem. No contemporary image of the reformer exists.

Andreas Bodenstein von

Karlstadt

A theological scholar who

supported deeper social-political reforms than Luther.

|

|

Ulrich Zwingli

In Zurich, Switzerland, meanwhile, a young priest was being drawn toward Luther's reform movement. In 1522 Ulrich Zwingli began to make his moves to establish Scripture as the sole religious authority for the Christian. He opposed the Lenten Fast, citing the lack of Scriptural warrant for the practice – a position which was supported by the Zurich civil government. The bishop of Constance tried to suppress this innovation – but lost out to the Zurich government, which moved to take control of ecclesiastical matters within its jurisdiction. Zwingli supported this shift in authority – claiming that the civil government, under the Lordship of Christ and guided in its work by the dictates of Scripture, was the legitimate voice or conscience of the believing community. Meanwhile the Reformation began to spread to other parts of Switzerland: most notably to the cities of Basel (where Oecolampadius had been leading the reform movement), Constance and Bern. It also made its way down the Rhine River to Strasburg – where under the leadership of Zell, Capito and Bucer the reform movement there took on the more thoroughgoing Swiss character (as distinct from the more conservative Lutheran variety). But the conservative rural cantons of Switzerland remained firmly opposed to the Zwinglian reforms. Relations grew bitter and hostilities resulted – with Zwingli himself being wounded and then put to death in a losing battle against the rural cantons in 1531. The more gentle-natured Heinrich Bullinger took over the Zurich reform movement. The Split within the Protestant Ranks

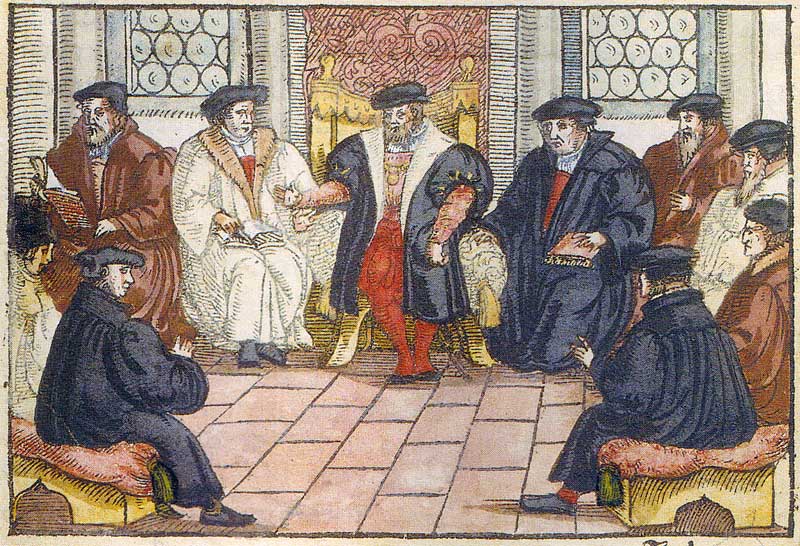

Meanwhile, the reform movement was beginning to move in different and opposing theological directions. For Luther the reform movement was more narrowly related to the matter of a sinner's personal justification before God. Luther showed little interest in making broader changes within Christianity beyond the throwing off of Roman spiritual authority – with its traditions of works-righteousness. Substantial changes in worship, for instance, were of lesser interest to Luther. Also the episcopal form of church government (rule by bishops) was kept by Luther – though with the understanding that the bishops were answerable to the local princes – not to Rome. But to Zwingli and the Swiss reformers (identified as the Reformed party) there were strong interests in restructuring the organization and practices of the church around its original constitutional base: Scripture. There was a stripping away of every feature of Christianity that could not be supported by Scriptural warrant. This was in keeping with Zwingli's humanist background – and its focus on the Greek and Hebrew origins of the church, and the sense that everything that was a departure from this classical age was a perversion of an original purity undergirding the church. This would not probably have kept Luther and Zwingli from working closely together – except that one portion of Zwingli's reforms were violently opposed by Luther: Zwingli's treatment of the celebration of the Lord's supper. Zwingli (for whom the sermon, not the celebration of the eucharist, was the central point of Christian worship) interpreted Christ's words concerning his presence in the wine and bread as purely symbolic. To Luther, this was a shocking diminution of the power of the real presence of Christ in the elements of the eucharist. The gap was, in both their minds, unbridgeable by the mid 1520s. Others of both parties tried to effect a compromise. But Luther, even after Zwingli's death, would not hear of compromise. Lutheranism and the Reformed faith split ... permanently. |

Portrait of Ulrich Zwingli

after his death 1531 - by Hans Asper

Winterthur

Kunstmuseum

The Religious Colloquium

of Marburg of 1529 - anonymous - wood carving (1557)

By invitation

of the Landgrave

Philipp of Hesse, Luther and Zwingli came to Marburg in

September of

1529.

They were accompanied by

some of their followers, Melanchthon

being among these.

They were to settle their

dispute about communion

... in which they were not successful.

|

| In

the meantime in France, John Calvin (1509 to 1564), as a young jurist,

was trying to convince the French king, Francis 1st, to give sympathy

to the reform movement. In 1536 he published his Institutes of the Christian Religion. This not only failed to convince the king, but also identified Calvin as a voice of religious dissent, not tolerated in France. Calvin was forced to flee France. In coming to Geneva, Switzerland, the protestant reformer Farel prevailed upon Calvin to stay in the city and help him with the reformed movement which was growing rapidly there. But for Calvin, this proved to be a stormy proposition. Geneva was an unruly city, and Calvin's natural bent toward orderliness and discipline made him many enemies in the city. In the spring of 1538 Calvin and Farel were banished from Geneva. He fled to Strasbourg, where the Reform movement was well established. But in 1541, the old group partisan to Calvin urgently requested his return to Geneva. Calvin somewhat reluctantly decided to make his return – but on his terms. Upon his return, Calvin organized (accepting many compromises with the city Council) the religious life of the city around his new Ordinances – the foundation of Reformed polity. Geneva in turn became identified under Calvin's leadership as the model Christian city, the "New Jerusalem" of Protestantism. Calvin was an urban European, steeped in the bourgeois mindset of the rising European urban "middle class." Calvin's interest in reform of the crumbling medieval moral-legal order involved importantly a vision of the new urban order as central to a purified Christianity. And his interest in reform did not limit itself merely to matters of religious doctrine – as was the case for Luther. Calvin truly was interested in a comprehensive reordering of every aspect of post-medieval life: political, economic, and social as well as theological. Importantly, he gave a theological rationale for the independent-mindedness of the urban commercial class – arming them with Scriptural justification for going their own way within God's creation. Indeed, he encouraged them to establish purified political-economic-social orders as a way of purging Christendom of its corruption and of bringing glory to God in Jesus Christ. He made their soul-searching independent-mindedness a matter of the greatest importance in their standing before God. They not only had the right to be accountable to God alone as sovereign over them – they had the Christian duty to see that this was the case. The supposition was that any earthly lord who positioned himself between them and God was going to be problematic in their "purified" relationship with God and their covenantal life in the purified Christian commonwealth. The followers of Calvin attempted to convince the rich and powerful kings of Europe that their movement had no treasonous instincts – and that they planned to be good citizens in the realms where they lived. The kings were not convinced. And rightly so. Everything about Calvinism pointed to the idea of these people being accountable to no earthly ruler but to God alone. Switzerland, which was the birthplace of Calvin's Reformed Movement was well recognized for its independent mindedness and refusal to acknowledge the rule of any princely lord over the land. No, Calvin's Reformed Movement, or "Calvinism" was destined to bring a clash with traditional princely and priestly rulers who claimed to rule by "divine rights." That was exactly what the Calvinists claimed for their own "self-rule": self-rule by divine right – even by divine imperative. There was no way these two mind-sets were going to work cooperatively.  For more information on Calvin For more information on Calvin |

Portrait of John Calvin -

anonymous - 1500s

Portrait of John Calvin -

anonymous - 1500s

Bibliothèque de

Genève

Institutio Christianae

religionis(Institutes of Christian religion). Geneva: Robert Estienne,

1559

This is the definitive and

fourth edition of Calvin's compendium of reformed theology;

the first edition

was published in 1536

Guillaume (William) Farel

(1580)

original portrait in Theodore

Beza's Icones

Unitarian Michael Servetus

(Miguel Servet) - by Christian Fritzsch

Spanish scientist and theologist

of the Renaissance. Burned at the stake in Geneva in 1553

Martin Bucer (1560) - by

Jean Jacques Boissard

original in Icones quinquaginta

vivorum held in British Library, London

|

|

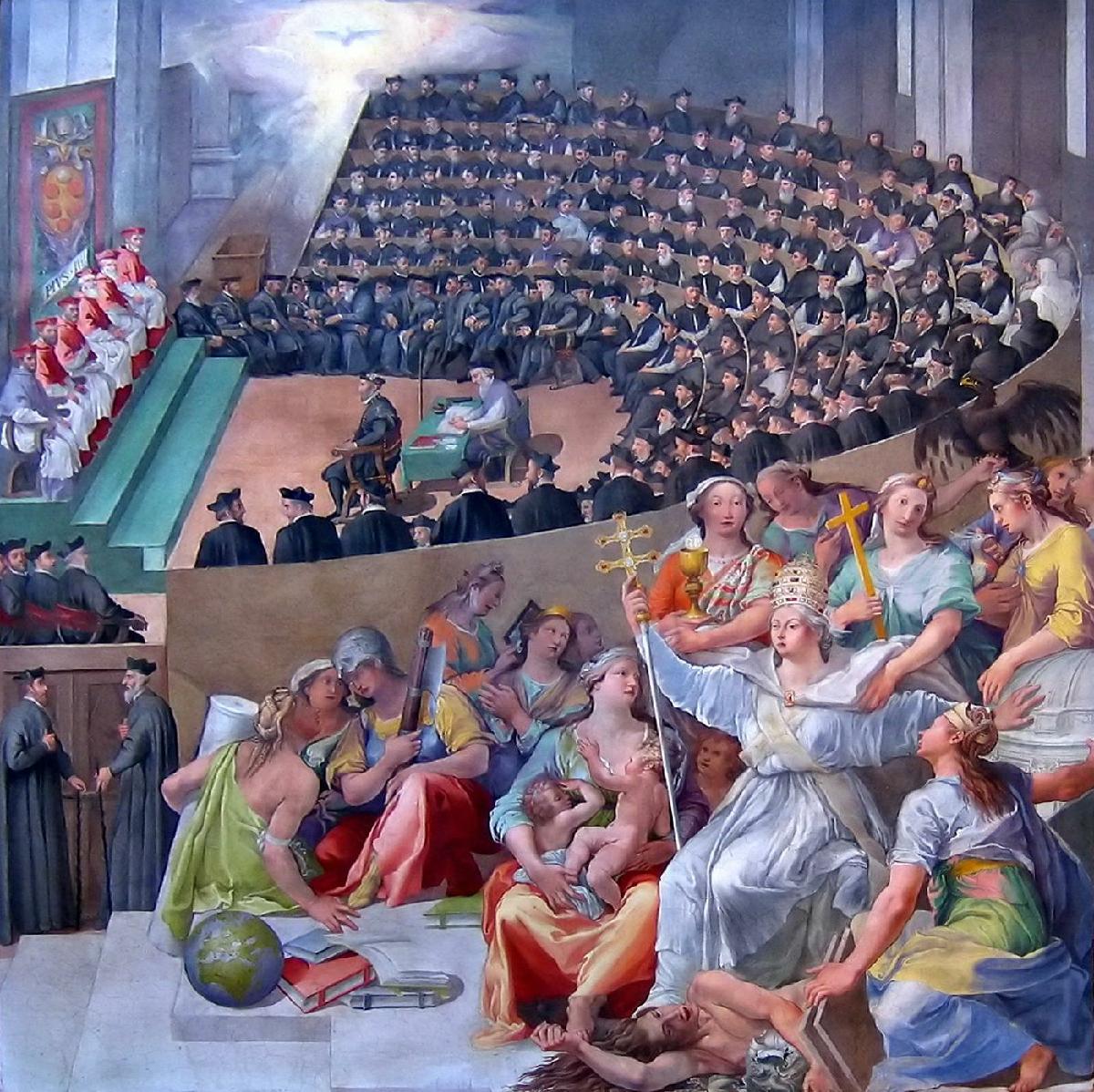

The "Counter-Reformation"

The papal party finally realized the seriousness of the challenge to its moral authority – and in 1546 called a Council at Trent to answer the Protestant charges of ecclesiastical corruption and theological deviation. Rigid discipline was reimposed over the priests who remained loyal to Rome. Luther's teaching on divine grace and justification alone by faith was condemned. A campaign was readied to wipe out any "heretics" not ready to return to Roman discipline. The war was thus on. The Roman church, championed by the most powerful ruling family in Europe (the Spanish Habsburgs) who were well-financed from their plunder of South and Central America – fought back cruelly, trying to stamp out the fires of the Protestant revolt. They succeeded in many places – and might have been fully successful had not the Muslim Turks attacked Vienna, the Eastern center of Habsburg power, during the height of this struggle. With the Habsburgs thus distracted, Protestantism dug in. |

Pope Paul III - who

convened the Council of Trent - painting by Titian

Naples, Galleria Nazionale

di Capodimonte

|

Pope Paul III and the Council of Trent

Paul III, under some considerable pressure by Spanish king Charles I, called the Council of Mantua (1537) to begin dealing with some of the issues of the reformation. But that Council got disrupted by a new round of warfare between Francis I of France and Charles. In 1542 Paul again called a Council, this time located at Trent (Austria) – thought it did not begin deliberations until the end of 1545. At the same time, Paul established the Supreme Tribunal of the Inquisition – a remake of the old Papal Inquisition which in the previous centry had largely been suspended in its operations. The revival of the Inquisition in Spain under the Spanish monk Thomas de Torquemada – who for 18 years used its techniques of torture in a very "successful" manner against Muslims, Jews and Christian heretics – no doubt persuaded Paul of its constructive use in stamping out heresy. But political realities kept Paul's wonderful scheme limited to Italy – where it did a masterful job of discouraging Protestantism among the Italians (as the Spanish Inquisition did in Spain). Paul's Council of Trent continued its meetings after his death in 1549, though he had by then clearly laid out the lines it would take. The Council of Trent met until 1552 (though it had to move to Bologna from 1547 to 1551 to escape an epidemic). After 1552 it did not meet again until 1562 and completed its work the following year. At the Council (as in his life) Paul took a very reactive position in the matter of the need for reforming the church. To him it was a straightforward matter of organizing the powers of the church to stamp out the Protestant heresy. But Charles was deeply desirous of reform in the church in order to steal the ideological advantage the Protestants enjoyed over a number of issues dividing the church. Charles wanted the church to tighten up its moral laxness and make significant compromises in matters of doctrine pressed by the Protestants – in order to restore unity within Christendom. But Paul held the line against anything that looked like a concession to the Protestants. Thus the Council of Trent, under his leadership, moved to anathematize (condemn) the Protestant position and to reaffirm the church's position that Tradition stood as a coequal with Scripture in determining church issues and doctrines. The Latin Vulgate was pronounced the only authoritative version of the Bible. No translations into the languages of the day would be allowed. Further, no copies of even the Latin Vulgatte were to be printed or distributed without authorization from church authorities. Also, the Council reaffirmed the doctrine that faith and works jointly formed the path to salvation – and not faith alone, which was a central Protestant position on the subject of salvation. Latin was to continue to be the language of the mass, the cup was to continue to be withheld from the laity during the sacrament of Holy communion, celebacy was to continue to be the order for the clergy – and a number of other doctrinal matters would remain unchanged. There were no doctrinal concessions to be made to the Protestants. However the Council did move to tighten moral discipline in the church – a major Catholic embarassment in the dispute with the Protestants. Clerical appointments were to be scrutinized more closely for moral-spiritual justification. Education of the clergy was to be stressed. And the preaching skills of the clergy were to be improved. Overall, the tightening up of Catholic doctrine made the church look much less confused in the face of Protestant challenges. And the new moral regimen removed the matters that were the most obvious source of popular discontent against the church among the people (most doctrinal issues escaped popular understanding anyway). Indeed, Pope Paul and the Council of Trent gave the Catholic Church a new crusading spirit against the Protestant "heresy." |

The Council of Trent - by

Cati da Iesi

(with allegorical figures

representing various virtues including 'the church triumphant')

The Founding of the Jesuits (Society of Jesus) by Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556)

- founder of the Jesuits - by Peter Paul Rubens (ealy 1600s)

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges