|

|

|

|

The role of the Emperor

It is not so simple to get a clear view of the culture of ancient China because up until about 1000 AD the Chinese kept detailed records of the names and deeds of the dynasties that ruled China ... and little else. General social and cultural history was not as important as keeping track of the many imperial dynasties that stood between the people and Heaven ... for that was the matter of the greatest urgency to the Chinese. Emperors were not, as we understand governing authorities today, just rule makers and policy enforcers. They were important religious figures, something like high priests, whose primary job was to present China before Heaven ... to bring bounty and security to China. If the Emperors failed at this divine task, China would be visited with devastating droughts, floods, plagues, locusts, bandits – and worst of all, the breakdown of central authority, allowing warlords to fight over and plunder China at will. In short, the Chinese emperors’ job was to maintain the ‘Mandate of Heaven. And how well the emperors performed this task was of the greatest importance to Chinese historians. They were not interested in the kind of socio-economic analysis that so fascinates modern secular historians attempting to discover the ‘natural’ causes of human events. The "Middle Kingdom" and its clans

The Chinese considered their society as something like a ‘Middle Kingdom’ (Zongguo): the heart of civilization ... a land and people surrounded by barbarians on all sides. This Middle Kingdom at first was a small regional grouping of Chinese tribes or clans along the Huang He or Yellow River (so named because of the mud that constantly washed down from the interior), which today forms the north-central and north-eastern portion of China. Key tribes or clans were the Zhou, the Lu, the Han, the Qin, the Wei, the Song, the Chen, the Wu ... each led by a small group of aristocratic families that conducted both friendly and not so friendly diplomatic relations with the other clans. It was one of the jobs of the emperor to keep the relations among the clans as friendly as possible. Confucius

But it would take centuries before the arrival in history of China’s first true military emperor – Qin Shi Huang (221-206 BC) ... who was able to knock heads among the clans to get them to behave. Prior to that there was only a sense of civil morality that kept things somewhat in check ... cultivated by the great Chinese teacher Confucius (Kong Fuzi – 551-479 BC) who during a particularly bad time of inter-clan warring attempted to insert some sense of rational morality among the Chinese clan leaders. He did not succeed in his own lifetime, but left behind a school of social philosophy that centuries later would serve as some kind of moral constitution for a China that was organizing around tough imperial power. Confucianist writings would be carefully studied by those seeking positions in government ... as China developed a literate civil service of Mandarin bureaucrats, scholarly officials who demonstrated through passing rigorous qualifying exams that they were familiar in detail with Confucianist morality ... and who would govern locally in the name of the Emperor exactly according to that moral code. For aristocratic-scholarly Chinese society, Confucianism was the heart of all that was good and worthy.  A portrait of Confucius by Wu Daozi (685-758 AD) from the Tang Dynasty Ancestor worship

Religiously or spiritually, the Chinese looked to Heaven not only for favor in this lifetime but as a place of residence of departed ancestors ... who, in keeping with the Chinese emphasis on the family as the key to all social order, looked to those ancestors to continue to intervene, now from their vantage-point in Heaven, on behalf of their descendants still living on earth. We call this religion ‘ancestor worship,’ but basically it was just good common sense for the Chinese to continue to honor family heads, even in death, so as to keep them on the good side of things going on in the family (ancestors could be serious trouble if not properly honored). So, from the emperor on down to clan and family patriarchs, the logic was fairly consistent: keep the powers of Heaven happy so that life on earth would continue to be safe and prosperous. Daoism (or Taoism)

The Chinese generally also had a deep reverence for the physical world around them – which could be both incredibly beautiful and bountiful ... but also intensely savage when floods, droughts, locusts descended upon the largely rural society. Daoism, supposedly formulated by the ancient teacher Laozi (was he real, merely mythical, or a combination of many similar teachers?), emphasized the importance of maintaining a simple harmony or balance with nature ... learning how to ‘go with the flow’ rather than try to beat back life. In Daoism there was always a suspicion about urban civilization, an artificial culture resulting from man’s effort to bring life under his own mastery with his walls, buildings, and public works ... and armies to defend these human artifacts. To the Daoist, it was better to keep things simple, natural, and harmonious with respect to nature and its incredible powers. Thus just as Confucianism was something almost like a religion to the upper class Chinese, Daoism served as a popular religion among the common people. Buddhism

Buddhism was a later import from India, thanks to Indian missionaries who in the 100s and 200s AD began to bring this greatly revised version of Hinduism across the Himalayan Mountains to Tibet ... and beyond that to the heart of China (and even further, to Korea and Japan). Nothing about Buddhism seemed to conflict with the ancestor-worship, Confucianism and Daoism practiced by the Chinese ... though there was some political competition at times between the Daoist and Buddhist monks and their imperial sponsors. In any case, the work of the Buddhist missionaries seemed to be greeted with fair success. Behind the success of Buddhism in China were the many written works or sutras translated into Chinese ... and the many Indian teachers who interpreted these works to the various Chinese, from the emperors on down to the common villagers. Buddhism sought to honor the Buddha himself by careful study and mediation on the high moral principles of the sutras ... which worked well with the Confucianists ... and then live simply and honestly according to those same moral principles, which worked well with the Daoists. One of the great teachers (again, real, fanciful or a combination of several teachers?) was the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma who founded the Chan (in Japan, Zen) school of Buddhism ... which carefully instructed and disciplined its disciples concerning the path to Buddhahood ... something close to Daoism in process ... though – in line with classic Buddhism – seeking the extinction of the sense of self (or release from mortal bondage and its concerns) ... and not just the mere harmony of the self with the surrounding world. |

|

|

The Emperor Huangdi and the Xia Dynasty (2600 to 1700 BC?)

Chinese

dynasties able to enforce some degree of unity of the various Chinese

clans date way back in history ... although here too it is difficult to

separate fact from fancy. The first Chinese dynasty listed in the

dynastic histories was the Xia Dynasty, reigning anywhere from 2600 to

1700 BC (?) with its famous, through probably highly mythical, Emperor Huangdi

(Yellow Emperor) as its possible founder. To him was attributed

the founding of a huge number of Chinese cultural items (writing, math,

law, tools – even sports) ... as well as having founded the ‘Han’

Chinese people and their social order. He in short represented

all the virtues by which the Chinese identified themselves as a highly

moral, highly civilized people living amidst the barbarian nations that

surrounded them. Chinese

dynasties able to enforce some degree of unity of the various Chinese

clans date way back in history ... although here too it is difficult to

separate fact from fancy. The first Chinese dynasty listed in the

dynastic histories was the Xia Dynasty, reigning anywhere from 2600 to

1700 BC (?) with its famous, through probably highly mythical, Emperor Huangdi

(Yellow Emperor) as its possible founder. To him was attributed

the founding of a huge number of Chinese cultural items (writing, math,

law, tools – even sports) ... as well as having founded the ‘Han’

Chinese people and their social order. He in short represented

all the virtues by which the Chinese identified themselves as a highly

moral, highly civilized people living amidst the barbarian nations that

surrounded them.The Shang Dynasty (c. 1766- 1050 BC)

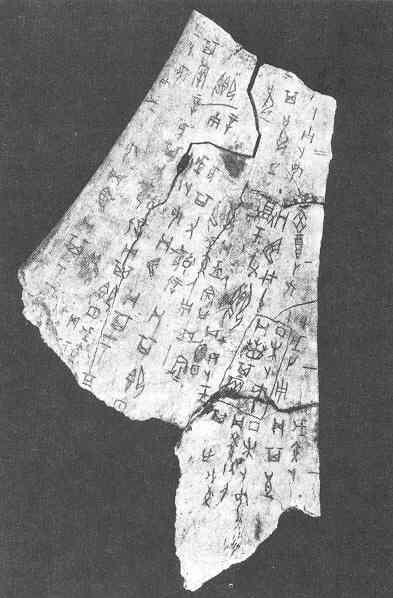

The next dynasty on record was the Shang Dynasty ... although it is not until the 1300s BC that we get any kind of detail about the dynasty other than the names of its emperors. This is when we get the first glimpse of imperial ancestor worship ... by which the Emperor approached his departed imperial ancestors for guidance in his ruling of the empire (just as clan and family fathers performed the same rituals for their respective societies). The Emperor was also expected to engage in the reading of the oracle bones1 which magically foretold the future. Both ancestor worship and reading oracle bones were the most critical jobs expected of the Emperor as China’s link to the Heavens. The emperor could of course be a conquering hero or political consolidator of the Chinese social realm. But he is best understood as China’s Chief Priest. This became even more the case ... when the effective area of Shang political rule became more and more reduced – as the Chinese regions became increasingly politically independent. 1These were turtle undershells or the shoulder bones of oxen that were heated and cracked ... the cracks providing divine answers (which the Emperor was supposed to be able to interpret) to particular issues. |

Chinese oracle bone pit at

the late Shang Dynasty capital of Yinxu (near modern Anyang)

Chinese oracle bone from

the Shang Dynasty

Columbia University (East

Asian Library)

Bronzeware excavated at the

tomb of Lady Fu Hao, Yinxu

Houmuwu Ding made in the

late Shang Dynasty at Anyang

This wine vessel is the

heaviest piece of bronze work found in China so far.

Height 133 cm, width 112

cm, depth 79.2 cm, weight 875 kg.

The National Museum of

China.

Chinese bronze wine vessel

from the Shang Dynasty

The Metropolitan Museum

of Art, Rogers Fund 1943

Bronze owl-shaped vessel

(zun), Late Shang Period (c. 1200 B.C.)

The Institute of Archaeology,

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing

National Gallery of Art,

Washington D.C.

Bronze two-sided mask, Late

Shang Period (c. 1200-1050 B.C.)

Jiangxi Provincial

Museum, Nanchang

National Gallery of Art,

Washington D.C.

Bronze standing figure, Late

Shang Period (c. 1300-1100 B.C.)

Sanxingdui

Museum, Guanghan

National Gallery of Art,

Washington D.C.

|

The Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045-770 BC)

Then appeared the Zhou Dynasty in the Western Shang territory ... when the Duke of Wu formally threw off Shang authority and announced himself as king. But upon the new king’s death two years later his brother, the Duke of Zhou, claimed that he possessed the "Mandate of Heaven" and thus took for himself the title of Emperor. This was the first specific mention in the Chinese history books of the Mandate of Heaven ... and the emperor’s critical role in courting the favor of Heaven (principally the emperor’s own imperial ancestors in heaven) in securing the right to rule. So excellent was his rule however that he became quite the model of what the Chinese felt that they had the right to expect of any emperor. He became the moral standard by which the Chinese emperors earned the loyalty of the Chinese people. Falling short of that standard would also create the opposite result: the right of the Chinese people to refuse to honor and support the emperor. Politically speaking, the Zhou government was something of a feudal system, with each of the Zhou Empire’s many regions having their own aristocratic governors (some of whom would become ancestors of later dynastic rulers of China) ... the whole thing held together by the military – and moral – strength of the emperor. At first (around 1000 BC) the Zhou emperors were so strong in holding and extending their rule across northern China that they were able to extend their reach ever southward ... expanding the Han Chinese population against other Asians (such as the Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians) so that the latter were forced to relocate themselves deeper and deeper into the South, until they came to occupy the large Indo-Chinese peninsula (where they are still located today). But despite the effort to strengthen the emperor’s rule in China with the buildup of a disciplined army and a professional bureaucracy, ultimately it was the personal strengths of the emperors themselves that determined the strength and stability of China’s imperial government. Over time that special leadership quality weakened, the regional governors became increasingly independent, and Chinese political stability suffered accordingly. For a brief period under the long reign of Zhou King Xuan (827-782), the Zhou Dynasty recovered some of its strength. But after that China fell back into a long period of disarray. Five centuries of civil strife

But then for the next five centuries China seemed lost in constant clan warfare: the Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 770-480 BC) and the Era of the Warring States (ca. 480-221 BC).2 At first the wars were fairly numerous but small, as they were fought among multitudes of small kingdoms. But over time as the actors got knocked out, one by one, and the contenders thus became fewer in number but larger in size, the battles became much more devastating to China. Thus it was that the social philosopher Confucius set out to try to put Chinese governance under some kind of moral restraint ... and the Daoist Master Laozi attempted to show the Chinese the path of retreat from the trauma of this warring period. 2Despite the rosy sound of the ‘Spring and Autumn Period,’ the term derives from the name of a written history, the Chungqui (The Spring and Autumn Annals). Actually it was a time of horrendous civil war among the many Chinese states ... as was also the ‘Warring States Period’ ... also named after a written history, the Zhanguoce. |

|

|

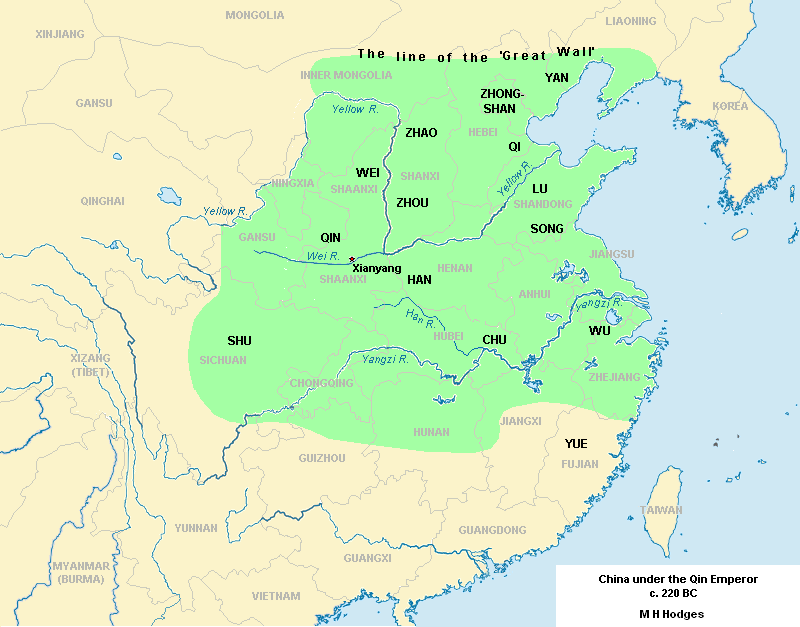

China unites under the Emperor Qin Shi Huang (220-210 BC)

Finally

the strongman Qin Shi Huang was able in 221 BC to force the clans to

come under his tough rule. The following year he dropped the term

king and took the title huángdì (the actual imperial title that would be used after him for the next 2000 years). According to Chinese history,3

he was brutal in the way he secured absolute power for himself over

China ... even burying alive hundreds of Confucian scholars (and

burning their libraries) ... supposedly in an effort to create a single

intellectual culture (his own legalistic culture) for China ... summed

up in a strict law code he put into place and enforced rigorously. Finally

the strongman Qin Shi Huang was able in 221 BC to force the clans to

come under his tough rule. The following year he dropped the term

king and took the title huángdì (the actual imperial title that would be used after him for the next 2000 years). According to Chinese history,3

he was brutal in the way he secured absolute power for himself over

China ... even burying alive hundreds of Confucian scholars (and

burning their libraries) ... supposedly in an effort to create a single

intellectual culture (his own legalistic culture) for China ... summed

up in a strict law code he put into place and enforced rigorously.In his ten-year reign as emperor he began the building of the Great Wall, he standardized both the Chinese currency and system weights and measures, and he laid in place the foundations of a cohesive bureaucracy (made up of legal scholars appointed through examination) operating under his precisely coded laws. But when Qin Shi died,4 he was replaced by an incompetent son (murdered), a couple of scheming officials (also murdered), and then an inept nephew (executed). Quickly the empire Qin Shi had built up split into a number of self-proclaimed kingdoms. 3However, such history is to be viewed with some suspicion because it was written a century after his rule by the Han Dynasty’s Confucian scholars, who naturally hated his memory. 4His burial was also the occasion of the creation of the terracotta army of 8,000+ soldiers – each individually crafted – plus hundreds of chariots and horses and various officials and court entertainers ... buried with him "to protect him in the afterlife." |

|

|

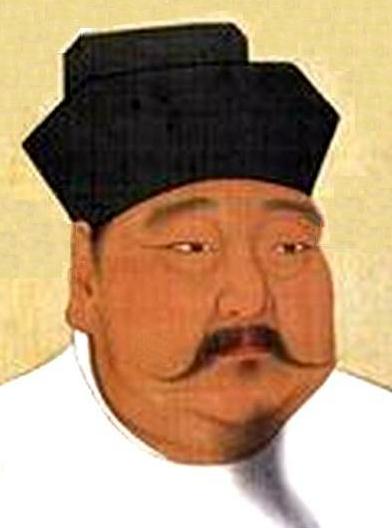

Emperor Liu Bang (Gaozu) ruled 202-195 BC

The

Chu leader then went on to destroy entirely the Qin capital (and

execute the last Qin emperor) ... but was then himself defeated in

battle (202) by his own lieutenant Liu Bang, prince of a small fief of

Hanzhong along the Han River. Liu Bang then went on to proclaim

himself Emperor (known posthumously in history as Gaozu or Emperor Gao)

and took for himself and his descendants the Dynastic name ‘Han.’

Thus the great Han Dynasty was born ... and in its four-century rule

give China its ‘Han’ character that it would carry down to today. The

Chu leader then went on to destroy entirely the Qin capital (and

execute the last Qin emperor) ... but was then himself defeated in

battle (202) by his own lieutenant Liu Bang, prince of a small fief of

Hanzhong along the Han River. Liu Bang then went on to proclaim

himself Emperor (known posthumously in history as Gaozu or Emperor Gao)

and took for himself and his descendants the Dynastic name ‘Han.’

Thus the great Han Dynasty was born ... and in its four-century rule

give China its ‘Han’ character that it would carry down to today.Emperor Gaozu took up immediately where Qin left off, building much of his governmental and economic structure on the foundations laid out by Emperor Qin. In the Western third of his empire he set up 13 commanderies which he governed more or less directly through bureaucratic supervision ... and in the Eastern two-thirds of his empire he set up ten kingdoms under the rule of his supporters in his rise to power. But he built the new Han moral code directing Chinese life on the teachings of Confucius ... setting aside portions of Qin’s Legalism and its harsh penalties (although he could be as tough as any emperor in dealing with rebellion). It was only in his dealings with the giant Xiongnu5 Empire to the north and northwest of China that Gaozu ran into difficulties. Han forces sent against the Xiongnu were defeated in 200 BC, and an agreement was negotiated between the two powers involving the sending by Chinese of expensive goods as tribute to the Xiongnu ... and the exchange of women between the two as royal wives. But sadly for China, at his death in 195 he was followed by a quick series of weak male offspring dominated by their respective mothers  Emperor Liu Heng (Wu) ruled 141-87 BC.

It was a grandson, Liu Heng, (son of a relatively humble imperial

consort) that finally was able to bring some stability back to Han

government. In cooperation with his Daoist wife, the Empress Dou,

Emperor Wu presided over a ministry of able advisors who helped him

bring China to such prosperity that the country’s warehouses were

bulging with overproduction of food. Emperor Liu Heng (Wu) ruled 141-87 BC.

It was a grandson, Liu Heng, (son of a relatively humble imperial

consort) that finally was able to bring some stability back to Han

government. In cooperation with his Daoist wife, the Empress Dou,

Emperor Wu presided over a ministry of able advisors who helped him

bring China to such prosperity that the country’s warehouses were

bulging with overproduction of food.It was Emperor Wu who first introduced the examination system by which Chinese officials were recruited into the Chinese bureaucracy. He also established imperial universities where Confucianism could be studied by those seeking entry into the ranks of Chinese government. Militarily, Emperor Wu was able to break Xiongnu power and open up diplomatic relations with societies to the West ... and to lay out the great Silk Road connecting China commercially with the world of the Mediterranean. He also expanded Han control deeper south in China, gaining dominion over a number of kingdoms well to the south of the Yangtze River ... reaching even into northern Vietnam. And he established commanderies in Korea. Emperor Xuan (ruled 74-49 BC). Following Emperor Wu’s death in 87 BC, the imperial title was fought over by his descendants, with much of the court intrigue led by various Dowager Empresses. Some stability was finally achieved by the regency of Huo Guang, the Marquess of Bowang. He would become famous for his unselfish service to the imperial government in finally securing in 74 BC the imperial title for Emperor Xuan – at a great personal risk to himself. Emperor Xuan was the great grandson of Emperor Wu, who however had grown up as a commoner because of the fall from power of his father and grandfather resulting from the court intrigues of the times. Huo Guang had recognized in the young Xuan a hardworking yet humble youth ... able easily to identify with the Chinese commoners and their challenges because of his own personal experience. As emperor, Xuan lowered the tax burden on the people, used a kinder hand in administering justice, and was wise in his choice of counsellors. But after Huo Guang’s death in 68 BC, he had the rest of the Huo clan put to death because of their continuing attempt to control imperial affairs ... the one dark mark on his otherwise highly lauded rule. The Xin interlude (8-23 AD)

The next Han emperors, Yuan (49-33 BC), Cheng (33-7 BC) and Ai (7-1 BC) found themselves caught up in succession crises as brothers and half-brothers struggled for power ... with Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun trying to keep the peace within the quarreling imperial family. Consort Fu, who was jealous of Dowager Wang, and the incompetence of Emperor Ai, who also died in 1 BC without an heir, finally threw Chinese imperial politics into such a crisis that the Wangs, who (except Dowager Wang) had been disgraced earlier by jealous rivals, were brought back to power as counselors to restore order to imperial politics.  Wang Mang (1 BC-23 AD).

At this point Emperor Ai’s 9-year-old cousin Ping was installed as

emperor ... although Dowager Wang’s nephew Wang Mang, serving as

regent, was effectively in charge of imperial affairs. At one point (AD

3) Wang Mang had to put down brutally a conspiracy to overthrow him,

led by his own son and by uncles of Emperor Ping. Then step by

step he moved to place himself in the imperial throne, poisoning

Emperor Ping ( AD 5) and forcing his aunt, Dowager Wang, to turn over

the imperial seal to himself (however, the aging Dowager Wang remained

a supporter of the Han dynasty all the way to her death in AD 13). Wang Mang (1 BC-23 AD).

At this point Emperor Ai’s 9-year-old cousin Ping was installed as

emperor ... although Dowager Wang’s nephew Wang Mang, serving as

regent, was effectively in charge of imperial affairs. At one point (AD

3) Wang Mang had to put down brutally a conspiracy to overthrow him,

led by his own son and by uncles of Emperor Ping. Then step by

step he moved to place himself in the imperial throne, poisoning

Emperor Ping ( AD 5) and forcing his aunt, Dowager Wang, to turn over

the imperial seal to himself (however, the aging Dowager Wang remained

a supporter of the Han dynasty all the way to her death in AD 13).As ‘Acting Emperor’ Wang Mang selected the 1-year-old child Ying as Han Emperor ... and then turned to put down the rebellions against his own rule. Then in AD 8 he simply took full title as Emperor and founded the new Xin Dynasty. He tried to infuse his new dynasty with legitimacy by reorganizing and renaming political offices and jurisdictions with ancient titles ... and expanding the role of the Confucian scholars as the foundation of his new government. He attempted to abolish slavery and to redistribute land more equally among the Chinese ... but failed of both counts to get the country to abide by his edicts. He also tried – and failed – to reform the country’s tax and coinage systems ... leaving the country more confused than helped through his efforts. When Xia officials ordered frontier communities to end the payment of tribute to the Xiongnu (who would raid and enslave Chinese women and children when tribute was not paid), a series of wars took place (AD 10-14) ... which resolved little and merely weakened the impression of the Xin Emperor’s ‘Mandate of Heaven.’ Likewise Wang Mang’s imperial troops began to have troubles keeping the clans of the Chinese Southwest under imperial order ... as well as some of the Korean clans. Also in AD 11 the Yellow River overflowed, destroying crops and causing a major Chinese famine. Slowly the Chinese people were beginning to believe that Wang Mang had lost the Mandate of Heaven. By AD 17 agrarian revolts (led principally by the Chimei or ‘Red Eyebrows’ and the Lulin) were breaking out across the land. At this point Liu brothers of the Han clan came forward to lead the restoration of the Han Dynasty. In AD 23 Han and Xin military met in battle ... which did not go well for the Xin. Han general Liu Xiu met and killed Xin general Wang Xun ... with Han forces crushing and sending fleeing surviving Xin troops. Then as Han forces approached the imperial capital at Chang’an, rebels rose up against Emperor Wang ... and killed him. Thus ended the brief Xin Dynasty. The (Eastern) Han restoration (AD 23-220)

The brief (Ad 23-25) rule of Han Emperor Gengshi. At first (AD 23) one of the Liu leaders, Liu Xuan, was named Han emperor (Emperor Gengshi) ... but was jealous of his cousin, Liu Yan, his prime minister. He had him executed ... then fell into remorse and named Liu Yan’s brother, general Liu Xiu, as Marquess of Wuxin. But this would not appease Liu Xiu ... who waited for the opportunity to dethrone his cousin. This opportunity first appeared in AD 24 when Chimei armies attacked Gengshi’s troops and defeated every army Gengshi sent against them. They then marched on Gengshi’s imperial capital at Chang’an (AD25), where a desperate Genshi executed a number of his generals who were plotting against him, then fled the capital as another general joined forces with the Chimei. Meanwhile Liu Xiu announced himself emperor as he began to take control of a number of Chinese provinces ... and also a compliant Luoyang, making it his capital city. But the Chimei also named their own emperor, the young Liu Penzi, to whom Gengshi surrendered (on condition of being named as a prince in exchange for his stepping down). But with the Chimei effectively in charge at Chang’an, Chimei soldiers began pillaging China ... to the point that the popular mood turned toward the idea of restoring Genshi to power. But that possibility was closed off when Gengshi was strangled.  Liu Xiu as Emperor Guangwu (AD 25-57).

Having secured most of China north of the Yellow River, Emperor Guangwu

(Liu Xiu) took on the Chimei armies one by one and brought about their

defeat (including Liu Penzi). He also brought other pretenders to

the Han throne plus local clans and their warlords under his authority,

bringing the last of them under his dominion by the year 36. Liu Xiu as Emperor Guangwu (AD 25-57).

Having secured most of China north of the Yellow River, Emperor Guangwu

(Liu Xiu) took on the Chimei armies one by one and brought about their

defeat (including Liu Penzi). He also brought other pretenders to

the Han throne plus local clans and their warlords under his authority,

bringing the last of them under his dominion by the year 36.Domestically he was noted for his more generous instincts in the matter of taxes and law enforcement. Once in power he experienced no further major wars, though he was quick to put down a Vietnamese rebellion led by the Trung sisters (AD 40). His battles with the Xiongnu were minor ... although constant raids by the Xiongnu in northern China did depopulate the region as the Chinese migrated south to get away from these raids. Eventually (AD 48) the Xiongnu themselves split into two contending kingdoms, north and south, with the southern Xiongnu becoming tributary allies to the Han in AD 50. In AD 57 Emperor Guangwu died and was succeeded by his son, Prince Zhuang (Emperor Ming). Emperor Ming (AD 57-75). Prince Yang (his name changed to Zhuang as he approached adulthood) proved at an early age to be very wise ... and even his father Emperor Guangwu consulted him frequently. Emperor Ming was generous in his treatment of his fellow family members (unusual for imperial families) – at least initially – yet very tough in his handling of corrupt officials. He was careful to bring dignity to the imperial office in the way he carefully followed Confucian doctrines in his rule. To strengthen the position of Confucianism in China he built an imperial university at his capital of Luoyang ... where children of Chinese officials could learn the Confucian classics so essential to the strong moral foundations of the Chinese bureaucracy. His generals were also able to pacify the North Xiongnu ... and secure the Silk Road to the West. It was during his reign that Buddhism began to make its strong entrance into China. But late in his reign Emperor Ming executed three Chinese rebellious princes who at different times betrayed his trust ... and who each sought to bring him down by having warlocks put curses on him! But in trying to get to the bottom of the plots, Ming allowed interrogators to torture and put to death any suspected fellow conspirators ... ultimately losing control over the process when people began to accuse each other wildly – and tens of thousands ultimately died as a result of the "investigations." Finally, under the urging of Empress Ma, the emperor backed down from the "investigations." Otherwise, he ended his reign in AD 75 with China at peace ... and very prosperous. Indeed, at this point the Han Dynasty reached the height of its power and glory. Emperor Zhang (75-88). Crown Prince Da, Emperor Ming’s son by way of Da’s adoptive mother Empress Ma, had been designated by Emperor Ming as his heir-apparent ... although Prince Da had numerous brothers older than him. Then when Emperor Ming died in AD 75, the 18-year-old Prince Da took the Chinese throne as Emperor Zhang. Emperor Zhang was of a kinder nature than his father and was quick to lighten the tax load of his Chinese subjects. This hard-working emperor was well-served by his counselors (including his adoptive mother, Empress Ma ... who however died only four years into his reign) and his military generals ... and in the latter case was able to continue to pacify the North Xiongnu and secure the Silk Road to the West. Thus the Han "golden age" put in place by his father continued under Emperor Zhang. But his rule would be troubled at the palace by the Empress Dou – whom he loved very much – who, after the death of the Dowager Empress Ma, moved to have her Dou relatives placed in key positions in the Chinese administration. At various times she and her Dou relatives falsely accused her competitor consorts Song and Liang of various acts ... in order to bring shame on them and their families and clans (suicide by poison being the usual result). Eventually Empress Dou’s brothers took over the effective governance of China ... beginning a trend (government by the Empress’s clan leaders ... challenged by other clans) that would continue through the rest of the years of the Han Dynasty ... and help bring about the decline of the dynasty. Decline of the Han Dynasty

From this point on, palace politics would be very messy ... leaving Chinese leadership in turmoil – and China along with it. Emperor He (AD 88-105) found out that Dowager Empress Dou was only his adoptive mother and that she was responsible for the death of his birthmother Consort Liang. Consequently, with the strong support of the eunuch Zheng Zhong, Emperor He arrested Dowager Empress Dou and had the entire Dou clan removed from power. But this merely cleared the way for Zheng Shong (and palace eunuchs after him) to move into the power vacuum created by the Dou purge. The lack of any direct heirs also complicated the question of Emperor He’s legacy. And clan rivalries promoted by the women of the palace also greatly weakened He’s rule. Also, during Emperor He’s reign, the Qiang people of Eastern Tibet revolted against Han rule because of the corruption of Chinese officials ... and the treatment the Qiang received as non-Han Chinese. The Qiang would remain in a constant state of rebellion for the next several generations ... further undercutting the image of Han power. In 106 Dowager Empress Deng was able to maneuver He’s 12-year-old nephew, Prince Hu, into the position as Emperor An (106-125) ... then continued quite capably to govern China as regent for the next fifteen years during Emperor An’s minority years (and after). Finally with her death in 121, Emperor An had full control of his government. But Emperor An was weak in character, easily influenced by those directly around him ... and was more interested in women and drink than the affairs of state. In any case the Deng clansmen in the palace were purged and the Song and Yan clans tended to take their place at the center of power ... although the eunuchs and other clan members challenged that power whenever possible. The messy state of affairs under Emperor He became even messier under Emperor An. Meanwhile the Qiang in the West and the Xiongnu in the northwest were joined in rebellion against Han authority by the Xianbei (a Mongol people) in the north and northeast. Han authority at the frontiers was slipping. Emperor An died fairly young and now Dowager Empress Yan tried to take control as regent ... but was opposed by the palace eunuch Sun Gheng. She was defeated, her clan (as always) purged (suicide by poison) and Emperor Shun placed on the throne (125-144). He was followed by the seven-year old Emperor Zhi, who ruled only two years rule before he was poisoned. He was followed by Emperor Huan (146-168) ... who took the throne at age 14. Again, a struggle between the Dowager Empress and the eunuchs to run China during the Emperor’s youth only inspired greater corruption within the Chinese government. When in 166 students rose up in protest against the corruption, Emperor Huan merely had all the students arrested ... and the corruption continued. Two years later, at age 36, Emperor Huan died ... with no son of his own to take his place. Once again, a jealous empress had another consort put to death before moving to have the 12 year-old Liu Hong selected as Emperor Ling (168-189) with full intention of reigning over China as regent ... except that she was strongly opposed by the eunuch Zhang Rang ... and she (and her father and clan) lost. During Emperor Ling’s 21-year reign, Zhang largely governed the country ... as the emperor was more interested in enjoying the sensual pleasures and happy to leave full responsibility to his ‘father’ Zhang. Corruption in the form of heavy taxes laid on the peasants and payments to Zhang and his cohorts for the purchase of public offices became so burdensome that revolts broke out all over China ... importantly the Taoist Yellow Turban sect which in 184 intended to overthrow the Han Dynasty and place its mystical leader Zhang Jioa over China. It took a number of Han armies sent out to defeat the Yellow Turbans – and the death of Zhang Jiao himself – to finally break the rebellion. But the rebellion(s) had left the power of the Han Dynasty so weakened that the Chinese provinces found themselves looking increasingly to their own leaders rather than the imperial government for keeping the peace in the land. When Emperor Ling died (189) Zhang Rang’s enemies came after him, and he ended his life by suicide ... along with thousands of other eunuchs subsequently executed by the Han military in the effort to end the eunuchs’ power over the palace. China’s new emperor was the 8-year-old Liu Xie (Emperor Xian of Han: 189-220) – the last of the Han emperors. But effective rule was now held by China’s military leaders – warlords actually. During battles among the warlords, Emperor Xian was merely a puppet, issuing directives of the warlords using his name as authorization. Actually General Cao Cao succeeded in bringing some degree of unity back to China ... but then in 208 lost in battle much of what he had gained and found himself sharing China with other warlords. Then when he died in 220 his position was taken by his son, Cao Pi ... who forced Emperor Xian to abdicate ... and who then proclaimed the founding of the Wei Dynasty. But he was quickly challenged by the Shu and Wu kings. 5Because they left no written records for historians to study, no one is still today exactly sure who the Xiongnu were – Mongols, Turks, Iranians, Huns or some mixture. |

|

|

The Three Kingdoms (220-280)

In any case the Han Dynasty had effectively come to an end ... replaced by three bitterly contending kingdoms, the Wei being the strongest of the three. Numerous individuals from these clans would adopt the imperial title ... but the reality was that China no longer benefitted from effective imperial rule. The Jin dynasty (265-420)

Another clan, the Jin, succeeded in 265 in overthrowing the Wei ... and going on to unify the country in 280 in defeating the Wu. But the unity was brief as rebellions broke out constantly ... and corruption and family squabbles within the ruling dynasties quickly undermined the unity of the Jin government. Also Jin rulers or ‘emperors’ were captured in battle and executed (Emperor Huai in 313 and Emperor Min in 316) greatly weakening Jin power. And it was a time of great turmoil among the Chinese commoners ... who migrated south (depopulating the north) to get away from the chaos – creating in the process something of a separate Chinese society in the south. Joined by the Sixteen Kingdoms (304-439)

But different peoples (the ‘Five Barbarians’) also migrated into northern China during this same period ... establishing their own (‘Sixteen’) kingdoms, thus further weakening the Jin claim to imperial rule. This chaotic period would end up qualifying as one of China’s darkest ages. The Northern Wei unify northern China

During this time period Xianbei under the chief Tuoba Yilu migrated into northern China from Mongolia and became "Sinified" (absorbed into Chinese culture) ... and eventually adopted the Chinese name "Wei" during the reign of Tuoba Gui, who in 398 declared himself Emperor Daowu. The Zhou begin a process of reunification

The path out of the disunity that marked China since the fall of the glorious Han dynasty was set by a non-Han Chinese warlord from western China, Yuwen Tai, who began to consolidate his holdings by bringing the northern part of China under his military discipline (utilizing extensively the fubing or commoner militias as the base of his power) ... and by cleverly portraying his rule as some kind of reversion to greatly romanticized ancient noble standards ... taking for his rule also the ancient name of Zhou. He also put restrictions on Buddhism and Daoism to emphasize the Confucianist (thus more purely Han) character of his rule. All of this was timed with a major weakening of the Chinese south when the Chen ruler brought the southern capital at Jiankang (Nanking) under his rule by starving and slaughtering the city of 1 million inhabitants (the largest in the world at the time) in 548. The greatly weakened South was thus a fairly easy pickoff by the new Zhou northern dynasty ... especially after the Chens lost an important battle to the Zhou army in 577. But two years later Yuwen Tai died and his rule was passed on to his notoriously brutal and amoral son Yuwen Pin. Emperor Wendi founds the brief Sui dynasty

But the key factor to holding Zhou gains in the face of imperial corruption was Yuwen Pin’s father-in-law, the duke of Sui – who took over governmental affairs and began putting down the rebellions which had broken out across the country. Then when Yuwen Pin died the next year (580) the duke finished off the last of the rebellions ... and then proceeded to eliminate members of the Yuwen clan. The following year (581) he took the title of Emperor, as Sui Wendi. When he then brought the Chen south to defeat in 589 (but showing impressive clemency to the defeated southerners), largely all of China was under his strong rule. China now had an emperor in fact as well as in name. Then Wendi sent out his armies and diplomats to deal with the surrounding peoples, bringing northern Vietnam into his orbit of control, and establishing working relationships with the Kingdom of Sulla (South Korea)6 in the East and the rising Turks and the far West. Being a devout Buddhist, Wendi lifted the Yuwen restrictions against Buddhism and Daoism ... but strengthened his government administration along even stronger Confucianist lines ... giving his government a more universal appeal among the people. Yet Emperor Wendi could be very tough on those who opposed his rule, executing many and imposing tough discipline even on his own family. Much wealth was lavished on Buddhism in the form of the new temples and statues erected in the hundreds of thousands. And he rebuilt his capital city, Chang’an, along truly monumental lines. The Emperor Yangdi

His

son Yangdi (who may have murdered his father in his impatience to

inherit his imperial title) was no less heavy handed in his rule ...

adding to that sexually and materially wanton ways that his father did

not demonstrate. Yet he largely continued his father’s plan of

disciplining Chinese governance – including rebuilding the examination

program by which local magistrates were selected – so as to bring to an

end the governmental chaos that had existed since the breakup of Han

China three and a half centuries earlier. His

son Yangdi (who may have murdered his father in his impatience to

inherit his imperial title) was no less heavy handed in his rule ...

adding to that sexually and materially wanton ways that his father did

not demonstrate. Yet he largely continued his father’s plan of

disciplining Chinese governance – including rebuilding the examination

program by which local magistrates were selected – so as to bring to an

end the governmental chaos that had existed since the breakup of Han

China three and a half centuries earlier. But the biggest achievement during Yangdi’s rule was the building of the Great Canal (605-611), linking the northern Yellow with the southern Yangzi rivers, with extensions branching off to connect even more of China politically ... and commercially. But the enterprise had involved the forced labor of many hundreds of thousands of laborers (men, women and children), forcing Yangdi to have to chose between using the men for his fubing army or his army of canal diggers ... leaving China in a state of frustration – and a spirit of revolt. Then with massive floods destroying China’s crops (610-611) ... plus the failure of a grand military venture in Korea (614) ... restlessness turned into full rebellion. In 616 Yangdi took refuge away from his problems by retreating to his adoptive south ... where he was murdered in 618 by one of his generals. The Mandate of Heaven had clearly been removed from the short-lived Sui Dynasty. But all the Sui political and economic achievements worked greatly to the benefit of the following Tang Dynasty, which continued onward directly from the point where the Sui Dynasty had left off. 6But the North Korean Kingdom of Goryeo (or Goguryo) remained successfully defiant of Sui ... and usually also of Tang ... China. 6But the North Korean Kingdom of Goryeo (or Goguryo) remained successfully defiant of Sui ... and usually also of Tang ... China. |

|

|

Emperor Gaozu (618-626) founds the Tang Dynasty

But

first, the rebellions springing up all around China had to be dealt

with. This is the point at which the Li family stepped forward to

take charge of the pacification of China. Li Yuan, Duke of Tang

(and related to Sui emperor by marriage), took charge of the process of

pacification even before the emperor’s murder. Then with Yangdi’s

death, Li Yuan went through the motions as imperial regent of installing

another young Sui offspring, Emperor Gong ... but soon answered the

urging of his supporters (and the call of Heaven) and set aside Gong

and named himself China’s new emperor (better known in history by his

title awarded after his death, "Gaozu," meaning progenitor or dynastic

founder) ... clearly putting before the Chinese a new dynasty, the

Tang, as China’s imperial rulers. Li Yuan spent most of his brief

reign putting down rebellions and bringing China under his

control. But he also kept most of the Sui officials in place,

making his move into the imperial office quite smooth by Chinese

standards. But

first, the rebellions springing up all around China had to be dealt

with. This is the point at which the Li family stepped forward to

take charge of the pacification of China. Li Yuan, Duke of Tang

(and related to Sui emperor by marriage), took charge of the process of

pacification even before the emperor’s murder. Then with Yangdi’s

death, Li Yuan went through the motions as imperial regent of installing

another young Sui offspring, Emperor Gong ... but soon answered the

urging of his supporters (and the call of Heaven) and set aside Gong

and named himself China’s new emperor (better known in history by his

title awarded after his death, "Gaozu," meaning progenitor or dynastic

founder) ... clearly putting before the Chinese a new dynasty, the

Tang, as China’s imperial rulers. Li Yuan spent most of his brief

reign putting down rebellions and bringing China under his

control. But he also kept most of the Sui officials in place,

making his move into the imperial office quite smooth by Chinese

standards.Emperor Taizong consolidates the imperial gains (626-649)

But

Tang Emperor Li Yuan was deposed by his ambitious son, Li Shimin, in

626. To consolidate his hold on the imperial office, Li Shimin

then had his brothers killed (a not uncommon practice in Chinese

imperial politics). He took the temple name Taizong ... by which

he is generally known in history. But

Tang Emperor Li Yuan was deposed by his ambitious son, Li Shimin, in

626. To consolidate his hold on the imperial office, Li Shimin

then had his brothers killed (a not uncommon practice in Chinese

imperial politics). He took the temple name Taizong ... by which

he is generally known in history. He had serious challenges to face in the form of the Turkish tribes to the north of China – strengthening under the growing power of the Eastern Khagan (or Khan of Khans) – and the Koguryo Korean kingdom to the northeast. A couple of attempts by Taizong to subdue Koguryo ended in humiliating failure. With respect to the Turks, Taizong attempted to profit from the internal rivalries of the Turks ... but did succeed in the exchange of a diplomatic mission and gifts with the Khagan, which both the Chinese and the Turks each chose to interpret as tribute being sent in submission by the other party! Anyway, it kept relations with the Turks fairly peaceful. Although Taizong was himself rather indifferent toward Buddhism, his rule marks the beginning of an important mission of a Chinaman, Xuanzang, to India through Tibet in his quest to create a deeper connect between Buddhist China and the Buddhist homeland of India. In this, despite incredible hardships involved in his personal pilgrimage, he was hugely successful, his return years later to China with multiple artifacts and a library of Buddhist works translated into Chinese having a huge impact on Chinese culture ... perhaps impacting Taizong, but certainly his successor, Gaozong. Chinese historians would treat Taizong as the model of imperial excellence ... a leader willing to listen to good counsel. The laws became codified, the bureaucracy trimmed back and closely supervised and the fubing militias organized and trained. He was such a thorough enforcer of the peace that the roads and towns of China became entirely safe for pilgrimage, travel, and commerce. While this may have been a bit of an exaggeration of the court historians, Taizong managed to keep that reputation as a model emperor all the way down to today. Emperor Gaozong (649 -683)

Li

Zhi was the third of Emperor Taizong’s sons by Empress Zhangsun (and

ninth of his total of 14 sons) ... but favored by the Emperor after

some of the older sons got caught up in an intense political rivalry,

one that was even partially aimed at the Emperor himself at one

point. Thoroughly loyal to his father, Li Zhi was considered

however to be of a weak personal constitution. But receiving the

throne upon his father’s death (a long illness) in 649 as Emperor

Gaozong, he chose wise counselors (most importantly his uncle

Zhangsun) ... and during the first years of his reign China

continued to experience the prosperity brought about during his

father’s reign. Li

Zhi was the third of Emperor Taizong’s sons by Empress Zhangsun (and

ninth of his total of 14 sons) ... but favored by the Emperor after

some of the older sons got caught up in an intense political rivalry,

one that was even partially aimed at the Emperor himself at one

point. Thoroughly loyal to his father, Li Zhi was considered

however to be of a weak personal constitution. But receiving the

throne upon his father’s death (a long illness) in 649 as Emperor

Gaozong, he chose wise counselors (most importantly his uncle

Zhangsun) ... and during the first years of his reign China

continued to experience the prosperity brought about during his

father’s reign. But conspiracies against him abounded in the imperial court itself, forcing the emperor to have to execute a number of high officials (including his sister). Then he lost all effective power to the intrigues of Consort (then Empress) Wu. The Zhou interlude (690-705)

Empress Wu Zetian attempts to install her own "Zhou" Dynasty (684-705).

At first only a consort, Wu succeeded through fantastic court intrigue

(and the moral weakness of Emperor Gaozong) to have the Empress removed

and herself installed in her place, had the sons who were in line to

receive the throne exiled or executed ... including even her own sons

... and finally took total control (around 655) of Chinese political

affairs with the failing health of her husband, the Emperor. With

Gaozong’s death in 683 she set aside her older son Li Zhe after only a

year as emperor (Zhongzong), replaced him with his 12-year-old brother

Li Dan as emperor (Ruizong). But she intended to remain the

effective ruler of China. Empress Wu Zetian attempts to install her own "Zhou" Dynasty (684-705).

At first only a consort, Wu succeeded through fantastic court intrigue

(and the moral weakness of Emperor Gaozong) to have the Empress removed

and herself installed in her place, had the sons who were in line to

receive the throne exiled or executed ... including even her own sons

... and finally took total control (around 655) of Chinese political

affairs with the failing health of her husband, the Emperor. With

Gaozong’s death in 683 she set aside her older son Li Zhe after only a

year as emperor (Zhongzong), replaced him with his 12-year-old brother

Li Dan as emperor (Ruizong). But she intended to remain the

effective ruler of China.Then in 690 she took direct control of the Empire as reigning Emperor, demoting Ruizong from Emperor to the rank of Crown Prince ... also forcing him to change his family name from his father’s Li to her family’s name Wu. She then announced that China was under a new dynasty (the Zhou, named after a famous dynasty of earlier days in Chinese history, which she claimed she was descended from) and took for herself the name Wu Zetian. She would rule China with an iron fist, keeping an eye on her empire through large body of secret police ... with her armies also quick to put down rebellions – which were frequent. To secure her rule she also ordered, on a rather regular basis, the exile or execution of numerous princes, princesses, counselors, scholars, generals and other officials – including twelve whole branches of the imperial family. On the other hand, the common people of China found her rule most acceptable, as prosperity continued in the countryside. She even moved some of the industrial dynamic that had long been focused on the Chinese northeast further west into the Chinese interior. She continued to support strongly the fubing, keeping military expenses low and the strength of her military up ... expanding the empire thereby to its furthest extent thus far ... even finally bringing Korea under Chinese imperial influence. She also received the first Arab Muslim ambassador to China in 651. She was partial to Buddhism and elevated it above Daoism (her husband’s family however had made much of the fact that they were supposedly descendants of Daoism’s founder Laozi) ... although she did order the Dao de Jing of Laozi to be added to the list of required reading by the imperial university students. She also opened (somewhat?) the examination system leading to civil service appointments to commoners (formerly only members of aristocratic families were eligible). Finally in 705 her unwise sexual adventures (at 80 years of age!) led her to be successfully overthrown in a palace coup and forced to give up the throne to her older son and briefly former emperor, Zhongzong. The Tang dynasty was officially restored. The short reigns of Emperor Zhongzong and Emperor Ruizong. (705-712)

Zhongzong (705-710). With his mother’s overthrow in 705, Zhongzong took back his position as emperor. But he was of a weak character (like his father) and in fact his wife, Empress Wei and her lover Wu Sansi (Wu Zetian’s nephew) actually ruled China. Zhongzong died in 710 (poisoned by the Empress Wei) setting up a scramble for power within the imperial household. Ruizong (710-712). Empress Wei’s intention of placing the young Li Chongmao on the throne – so that she would be able to control China (like Wu Zetian) – was challenged by the sister of Zhongzong and Ruizong, Princess Taiping ... in company with Li Longji, son of the former Emperor Ruizong. The two moved swiftly against Empress Wei (who died in the coup), placing Ruizong back on the throne as emperor and Li Longji as crown prince. Zhongzong (705-710). With his mother’s overthrow in 705, Zhongzong took back his position as emperor. But he was of a weak character (like his father) and in fact his wife, Empress Wei and her lover Wu Sansi (Wu Zetian’s nephew) actually ruled China. Zhongzong died in 710 (poisoned by the Empress Wei) setting up a scramble for power within the imperial household. Ruizong (710-712). Empress Wei’s intention of placing the young Li Chongmao on the throne – so that she would be able to control China (like Wu Zetian) – was challenged by the sister of Zhongzong and Ruizong, Princess Taiping ... in company with Li Longji, son of the former Emperor Ruizong. The two moved swiftly against Empress Wei (who died in the coup), placing Ruizong back on the throne as emperor and Li Longji as crown prince. Emperor Xuanzong (712-756)

But

Emperor Ruizong abdicated after two years, taking the position as

"retired emperor," (though keeping much of the effective rule of China

still in his own hands ... at least during the next year), elevating Li

Longji to the imperial throne as Emperor Xuanzong. But that next

year (713) rumors of a coup being planned by Princess Taiping led

Emperor Xuanzong to move first, resulting in the death of the Princess

and a number of her followers. This would mark the effective

beginning of Emperor Xuanzong’s actual rule. But

Emperor Ruizong abdicated after two years, taking the position as

"retired emperor," (though keeping much of the effective rule of China

still in his own hands ... at least during the next year), elevating Li

Longji to the imperial throne as Emperor Xuanzong. But that next

year (713) rumors of a coup being planned by Princess Taiping led

Emperor Xuanzong to move first, resulting in the death of the Princess

and a number of her followers. This would mark the effective

beginning of Emperor Xuanzong’s actual rule.The early years (the Kaiyuan era, 713-741) of the reign of Emperor Xuanzong were marked by such excellent rule that Tang China reached an even greater height of culture and regional power. His chancellors, Zhang Yue (1721-1726) and Liu Youqiu (among many others) were a very important part of Xuanzong’s early success. He cleared out Wu’s much hated secret police, placed very effective military governors in the regions bordering the Turkish lands, reduced the size of his armies along the northern borders – granting salaries to those who now served – and restored to grand importance the sacrifices to Heaven at Mount Tai. China prospered. But during the latter years of his reign (the Tianbao era, 742-756) Xuanzong left governance to his chancellors and his regional governors (the jiedushi) and instead indulged himself with the tens of thousands of beautiful women brought to his palace. In time he was betrayed in his trust of his counselors, principally Li Linfu (734-752), a scheming chancellor who used his office to benefit himself handsomely rather than work to the benefit of the imperial government itself. Also in 751 Xuanzong’s armies lost the Battle of Talas against the Muslim armies of the Abbasid Caliphate, and thus outlying territory in the West now fell under Muslim dominion. As far as chancellors went, Yang Guozhong took up where Li Linfu left off and thus the corruption continued. Rebellions now began to break out here and there around the empire. Rumors of plots and counterplots (including a number of executions) among those surrounding the emperor now began to break out. Xuanzong’s government found itself in deep trouble. The An Lushan Rebellion. The worst for Xuanzong came when General An Lushan (a bitter rival to Yang Guozhong) planned and then commanded a massive uprising against the Emperor in 755. An Lushan proclaimed himself as emperor and founder of a new Yan dynasty. The emperor lost heart (the Imperial Guard assassinated Chancellor Yang Guozhong and the wily Consort Yang) and fled Chang’an (his imperial capital) ... and turned the imperial throne over to his son Suzong, letting him deal with the chaos (although as ‘retired emperor’ he occasionally manipulated things from behind the scene; however he died in 762, a worn out and depressed version of his former self). |

|

Dynastic decline

The new emperor Suzong found dealing with the An Lushan rebellion a bit easier when An Lushan’s son assassinated his father (757) in order to gain his own imperial position ... but actually weakening his position in the process. Emperor Suzong was able to recapture the capital Chang’an soon thereafter. But the An Lushan Rebellion would last over five more years, further weakening the political position of the Tang Dynasty. Although much of the north of China would be brought back under Tang rule, the Western Regions (Arab and Turkish Sogdian and Uighur regions) would now go their own way. Now the jiedushi (regional governors) began to take up the ancient role of local warlords ... collecting their own taxes to finance their own separate governments, thus fracturing China’s basic political unity achieved under the Sui and first Tang emperors. The imperial bureaucrats selected by careful examination would be ignored ... and then abandoned as a tool of the increasingly merely nominal figure of the emperor. A brief revival under Xianzong (805-820)

At

first the weakening of the hand of the imperial government freed up the

economy ... and China actually seemed to prosper a bit with the rise of

the merchant class in the latter part of the 700s. Then in the

early 800s the Tangs once again came under a strong hand, that of

Emperor Xianzong. He cut back the power of most of the jiedushi

with his own rebuilt imperial army in order to restore Chinese

political unity. But tragically, his successors did not

demonstrate any of the same talents for rule. China now slid back

into political trouble ... one that would grow deeper with the passing

of time. At

first the weakening of the hand of the imperial government freed up the

economy ... and China actually seemed to prosper a bit with the rise of

the merchant class in the latter part of the 700s. Then in the

early 800s the Tangs once again came under a strong hand, that of

Emperor Xianzong. He cut back the power of most of the jiedushi

with his own rebuilt imperial army in order to restore Chinese

political unity. But tragically, his successors did not

demonstrate any of the same talents for rule. China now slid back

into political trouble ... one that would grow deeper with the passing

of time.Full decline of the Tang Dynasty (820-960)

For the masses life once again began to be very difficult. Battles among rival warlords would destroy farmlands and villages. The roads would be infested with huge bands of robbers and the rivers by teams of pirates. And a Mongolian people to the northeast, the Khitans, were growing ever more powerful ... eventually establishing their own Liao Dynasty – one which would pose a direct challenge to the independence of Chinese society ... at least in the north. The masses knew that Heaven was angry and that the Mandate of Heaven had passed from the hands of the Tangs ... though it would take many more generations of ‘would-be’ emperors until that Mandate was clarified with the rise of the Song Dynasty in around 960. In the meantime, China suffered terribly. The worst came during a massive rebellion (874-884) in which the entrepreneurial Huang Chao challenged Tang authority by eventually (878-879) attacking the port city of Guangzhou (Canton) and massacring the Arab and Persian merchant population there ... and then marching on the Tang capitals at Chang’an – forcing the Tang Eperor Xizong to flee. Huang Chao then declared himself Emperor and head of the new Qi Dynasty ... which, however, lasted only until his death (at the hand of his nephew) in 884. The Tang dynasty was thus ‘restored’ ... although its power at this point was largely only symbolic. The era of the "Five Dynasties" and "Ten Kingdoms" (907-960)

By the early 900s there were five dynasties (Liang, Tang, Jin, Han and Zhou) ruling northern China in rapid succession ... the middle three actually Turks who had adopted Chinese culture and ruled as Chinese dynasties only in the northern portion of China. All five dynasties originated – as with all dynastic founders – had been founded by "usurpers," military governors originally serving under the Tang. Each dynasty claimed to possess the Mandate of Heaven; each dynasty however was short-lived: the Later Liang (907-923), the Later Tang (923-936), the Later Jin (936-946), the Later Han (947-950) and the Later Zhou (951-960). The founder of the Later Liang had murdered two Tang Emperors on the road to power, the Khitans then helped the Tangs overthrow the Liang ... but brought the Tangs – and after them especially the Jins – under Khitan mastery. So weak were these ‘dynasties, that at one point (946-947) the Khitans even seized the Jin capital at Kaifeng. The Hans recovered Kaifeng and some of the prefectures under Khitan dominance ... but they were soon overthrown by a rising Zhou power. Despite the chaos (and it was quite severe) this period saw some key advances in Chinese culture ... notably the block printing of all the Confucian classics (some 130 volumes) and the introduction of paper money in the form of bankers’ promissory notes. In both areas the Chinese would be centuries ahead of the West in the development of printing and banking. At the same time that the Five Dynasties were savagely replacing each other one after another, in the south of China ten smaller but more stable kingdoms were able to operate regionally with some degree of security and prosperity. This contrast in living conditions thus caused the massive migration of many Han Chinese from the north to the south. Also, a huge growth in the population occurred – principally in the prosperous south, where by the early 900s 60 percent of the 100 million Chinese now lived. The Khitan Liao Dynasty (907-1125)

Abaoji (ruled 907-926). To the north of the Five Dynasties (centered in modern Manchuria) was the semi-Chinese, semi-Mongol empire of the Khitans, headed after 907 by the Liao Dynasty. Its empire constituted most of Mongolia, northern Goryeo (Korea), and northern China. Its founder, the Khagan Abaoji was a mighty conqueror who grew up amidst violence and succeeded in turning the hard lessons he had learned from life to the art of conquest. But he was also a highly intelligent ruler, administering the northern portion of his empire through traditional Khitan principles (rule through feudal lords) at the same time directing the southern portion of his empire along Han Chinese bureaucratic lines (his bureaucracy heavily staffed by Han Chinese). Although Khitan tribal leaders saw their own powers eroded through this system, so successful did it prove in governing the empire that it would remain as the principle system of governance from that point on. The Khitans and the Han Chinese. Khitan culture differed strongly from the Han culture of the Chinese ... especially in the role of the sexes, women frequently occupying key political positions – not by usurpation but by right, according to the Khitan moral code. Given the shortness of life among the warlike Khitans, many claimants by birth to a newly vacated imperial throne would be just boys ... and fall under the supervision of their mothers (or even imperial concubines) – women who often continued to lead even after the boys reached manhood. We have already seen how the Khitans dominated politics in northern China during the Five Dynasties period. And even with the rise of the more enduring Song Dynasty, the wars between the Khitans and Chinese would be constant. Finally after much bloodshed, the Khitan and Song Empires agreed to a Treaty (1005) ... establishing a fixed border and offering a century of peace between the two peoples (at the high price of tribute that the Chinese were required to pay the Khitans). This would be the first instance of the Chinese having to live at the toleration of a Manchurian/Mongol people ... one followed up by Jurchen, Mongol, and Manchu supremacy. But the Chinese learned to adapt to this awkward relationship ... and continue to develop along their own cultural and economic path. Thus in a sense Chinese history at this point began to follow a two-path development of Han Chinese to the South and Manchurian/Mongolian people to the North. |

|

|

Taizu of Song (960-976)

Following

the typical pattern of the ‘Five Dynasties’ period, in 960 Zhou

military commander Zhao Kuangyin rose up against Zhou Emperor Gong,

forcing him to abdicate ... and taking command of (Northern) China

himself as Emperor Taizu of Song. But unlike the other dynasties,

the new ‘Song’ Dynasty would prove to have lasting qualities ...

although it would take some time to certify this fact. Following

the typical pattern of the ‘Five Dynasties’ period, in 960 Zhou

military commander Zhao Kuangyin rose up against Zhou Emperor Gong,

forcing him to abdicate ... and taking command of (Northern) China

himself as Emperor Taizu of Song. But unlike the other dynasties,

the new ‘Song’ Dynasty would prove to have lasting qualities ...

although it would take some time to certify this fact.During his 16-year reign the new Emperor Taizu defeated other Chinese states, starting with the smaller and weaker kingdoms in the south, broke the power of the independent warlords, replaced China’s effective governance by civilian administrators answering solely to him, and thus brought under his effective rule largely all of China – that is, China south of the territories in the north held by the Khitans in the northeast and the Xia in the northwest. Although the Tang rulers had themselves used civilian administrators (chosen through an examination focusing on the Chinese classics in literature), Emperor Taizu increased the number of schools preparing young men for just such examinations ... and actually made the administrators who came to office through the examination system the vast majority of his governing officials. And he was able to reward amply his generals in taking their retirement from active duty ... considerably cutting back on the conflicts that had previously torn China apart. He also proved to be a major patron of the arts and the development of science and technology. Under his governance, China began a long period of relative peace and prosperity ... at least to the south of China away from the troubled northern borders with the Khitans and Western Xia. With the signing of the Shanyuan Treaty of 1005 with the Khitans, the realm of peace would expand considerably. |

|

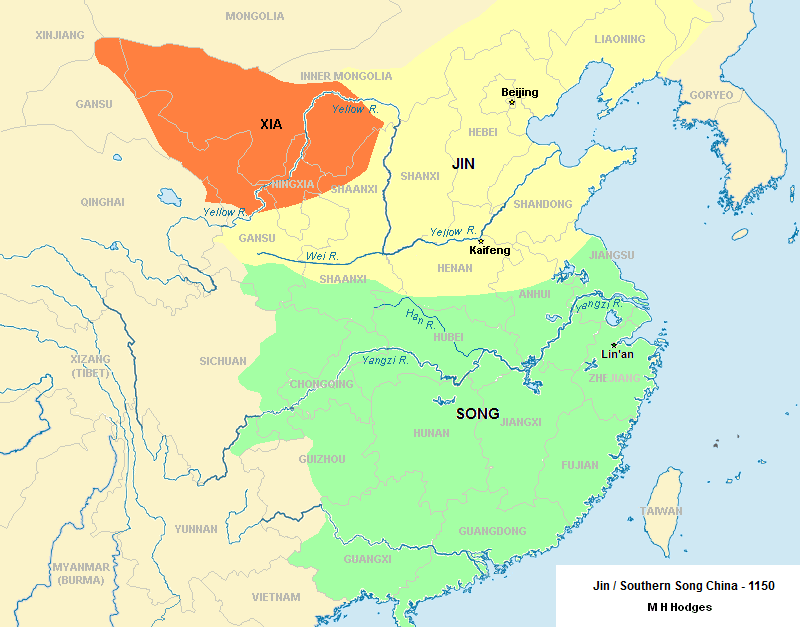

The Period of the Northern Song (960-1127)

In fact, this period of peace and prosperity performed some major cultural developments in China. The population recovered to its previous Han and Tang size, 50 million people according to official figures ... although the population was likely much larger than that. This stability – and accompanying economic development – allowed tremendous development of Chinese society ... still united politically under the leadership of the Song Emperors, but locally very dynamic in the conduct of economic, social and cultural affairs. Somehow China’s fate seemed less dependent on the dynamic of imperial court politics – and the doings of the emperors. This was in great part due to the transference of governing dynamics from the Chinese military to the Chinese Confucian bureaucracy ... the former seemingly less necessary for the good order of China – and the latter ever more tightly disciplined by the exacting Confucian moral code that guided closely the conduct of Chinese government throughout the Empire. During this period commerce and trade were greatly facilitated by the expansion of coinage – and also the use of paper money and sophisticated banking methods. Chinese trade and investment societies formed for the purpose of investment and the protection of professionalism in industry. Industry everywhere boomed ... especially iron production – thanks to the substitution of coal for charcoal, making the process cheaper ... and less threatening to China’s forests! Canals were dug to facilitate internal trade ... and a huge navy was developed to protect China’s overseas commercial shipping. Some of the cultural achievements of Chinese society during this period are outstanding. Literacy spread widely because of the growth of Chinese printing ... thanks not only to the wide use of block printing but also the development of moveable type – a discovery in the 1000s five centuries before the same discovery was made in the West in Europe. Consequently, this period in Chinese history saw great development in the world of literature, philosophy, science, art and architecture as well as scholarship in general. And religiously, it was a very active period, with movement back and forth between India and China by numerous Buddhist monks. But huge numbers of Muslims, Persian Manichaeans and even Jews made their way to China ... to do commercial business as well as engage the Chinese with their religions. Settled conditions also allowed more leisure ... and thus time for festivals, social clubs, sporting events and theater ... all of which developed to a highly sophisticated degree. |

| Court

politics of course continued as usual ... although it tended to focus

more on policy than personality. For instance, efforts in the

1040s by imperial Chancellor Fan Zhongyan to reform the methods of

recruiting and administering the huge Song bureaucracy, to increase its

effectiveness both in local government and in imperial defense, met

with stiff resistance from the older members of the court who felt

threatened by these reforms ... and ultimately Fan was banished to the

provinces. But his reform efforts would be taken up again only a

few decades later when Emperor Shenzong (1067-1085) gave full backing

to his Chancellor Wang Anshi for just such reforms. Mounting problems with the Jurchen’s Jin Dynasty to the north. But the peace of the north would be broken when in 1115 a subject tribe of the Liao, the Jurchen, rose up against their Liao masters and declared their own "Jin" Dynasty. The very artistic but politically weak Chinese Emperor Huizong was advised by his eunuch advisor Tong Guan to ally with the Jurchen in bringing the Liao Dynasty to an end (1125). But then the Jurchen or Jin turned on Huizong when the greatly weakened condition of the Song military became obvious, seizing the Song capital at Kaifeng and capturing the Emperor and nearly all of his Imperial court in 1127. The Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115-1234)

Remnants of the Song Dynasty were able to escape south of the Yangtze River and reposition their government at Lin’an (modern Hangzhou) ... and carry on much as before – although with only the southern half of China to claim as their own. The Jurchen Jin now ruled what was formerly northern China from their capital at Yanjing (modern Beijing). Both Empires considered themselves to be the true Zhongguo (Central Kingdom or State) ... that is ‘China.’ The battle between the two Chinas would at first be fierce ... until 1141 when a treaty outlining the border between the two Empires was signed (allowing a brief period of peace) and then another treaty in 1164 ushered in a longer 40-year period of peace between the two societies. The Jurchen were not ethnically Han Chinese, but quickly adapted Han culture as their own ... and (according the the natural bias of the court historians) were well received as their new dynasty by the Han Chinese clans living in the newly conquered Jurchen territory. But Jurchen Emperors would have troubles with their own Jurchen noblemen (and from time to time Khitan troops), facing rebellions as they attempted to solidify their power Han-style. The period of rule by Emperor Shizong (1161-1189) and his grandson Emperor Zhangzone (1189-1208) marked the height of Jurchen prosperity and strength. Emperor Shizong tried to support Jurchen culture (having Chinese classics translated into Jurchen) ... as did his grandson ... although Emperor Zhangzone was also a great lover of Han culture. The Southern Song carry on (after 1127)

When the Song Imperial government retreated south with the rise of the Jin Empire, life largely continued as it had before when the Song Dynasty had ruled the whole of China … with the exception of the wars with the Jin that waged on and off constantly. With its trade routes by land to the West now cut off by the hostile Jin, Song trade took more eagerly the sea route … necessitating even more a strong navy … established as a permanent feature of Chinese defenses in 1132. But this same navy also enabled the Song (also using new paddlewheel boats) to achieve a victory against the Jin in battles on the all-important Yangtze River (1161) … in which the Song launched gunpowder bombs at the much larger Jin navy throwing the latter into confusion and handing the Song a great victory... and ultimately the peace treaty of 1164. Genghis Khan

Then

at the beginning of the 1200s an event to the north of the Jin Empire

took place that would shake up not only China, but all of Asia ... and

even Eastern Europe. The Mongol Khan, Temüjin, had proved so

successful in his consolidating Mongol power in the north that in 1206

he took for himself the title Genghis Khan (universal governor) ...

announcing to the world the arrival on the political scene of a great

new military power. Then

at the beginning of the 1200s an event to the north of the Jin Empire

took place that would shake up not only China, but all of Asia ... and

even Eastern Europe. The Mongol Khan, Temüjin, had proved so

successful in his consolidating Mongol power in the north that in 1206

he took for himself the title Genghis Khan (universal governor) ...

announcing to the world the arrival on the political scene of a great