Who were the

Cathars or Albigensians?

-

As Europe finally

shook off the economic hardship of the Dark Ages (500 - 1100 AD) and began

to step out into a much larger, and very fascinating world, Europeans began

to break out of the mental and spiritual straitjacket that had held their

minds for centuries. Many Europeans became fascinated not just with

the wealth of the Muslim East--but also the way Muslims thought, especially

about spiritual matters.

-

By the late 1100s

Crusaders had brought back from the East a strange brand of Muslim mysticism

called by its Greek name,

Catharism (the "Pure People").

Europeans were sick of the power games and the moral corruption infecting

the traditional church. Large numbers of people in Italy, southern

Germany and southern France hungered for a lifestyle that would bring them

back into a sense of a closer relationship with God. Thus Cathar

mysticism--along with its very strict moral code--began to spread quickly

and extensively in Europe.

-

The Catholic church

grew very alarmed at this heresy--for it was stirring an enthusiasm among

the people that the church couldn't match. The church thus decided

to strike back and in 1184 the Roman Pope called for a crusade against

the Cathars (they were known as "Albigensians" in Southern France).

"Crusaders" were turned loose on the Cathars: they were authorized

by the Church to kill the Cathars and were awarded whatever lands they

were able to take from their helpless victims.

-

The Crusade proved

to be so devastating among the Albigensians in Southern France that it

completely destroyed a beautiful Southern French cultural "awakening" and

left the land and people devastated for centuries to come.

Why were Peter

Waldo and the Waldensians persecuted by the church?

-

At about the same

time, in around 1175, a devout Frenchman named Peter Waldo began

to call Christians to the task of teaching and spreading the gospel.

The heart of their teaching was scripture--rather than the traditional

teachings of the Catholic church. Very soon Waldo and the "Waldensians"

were having a strong appeal among a European people hungry for spiritual

teaching.

-

The church reacted

to Waldensianism the same way that it did to Catharism. Thus in 1184

Waldensianism was condemned by the Church right along with Catharism, despite

the fact that Waldo's teachings were very traditional in their Christian

theology.

-

The Church did

not want to be challenged in its authority by "upstarts" from outside the

hierarchy of professional priests--no matter how truly Christian the teachings

of these upstarts might be. Thus Waldo and the Waldensians were chased

out of Germany, France, and most of Italy. But Waldensianism survived

in the mountainous hideaways in the Swiss and Italian Alps--where over

300 years later it was eventually incorporated into the Protestant movement

that began to sweep Europe in the 1500s.

How

did St. Francis avoid the same fate?

-

It was not much

later that an Italian named Giovanni Bernardone, nicknamed "Francis"

because he loved to travel so much with his merchant father to France,

started a spiritual movement of his own, "rebuilding" the Church as a voice

of God instructed him to do. He and his followers, called "Franciscans,"

gave up all their personal wealth to serve the poor, the sick and

the unschooled people in the name of Jesus Christ.

-

He too came close

to being condemned by the Roman Church. But he had strong supporters

in Rome. In 1215, by finally and reluctantly agreeing to bring his

movement under Church discipline (although he feared that by doing so his

movement would end up being drawn back into the politics of the wealthy

and powerful Church) Francis avoided being declared a "heretic."

-

Indeed so popular

was Francis and his work that the Church had to recognize him soon

after his death as a true "saint." His movement, the Franciscans,

continued their work of teaching and charity long after him. In fact

the Franciscan Order is still in existence today.

What was Christian

"mysticism"?

-

The monasteries

had long been places of refuge (even since the last days of the Roman Empire)

where common people could remove themselves from a corrupt and cruel world

in order to devote themselves to worshiping and serving God. These centers

of learning and faith had kept the small light of Western culture alive

during the long run of the "Dark Ages" from the late 400s to the mid 1000s

AD.

-

Now that the West

was coming out from under the long period of invasion from Germans, Arabs,

Vikings, Hungarians, Bulgars, etc., and now that wealth and power were

returning to the West, the European Church found itself in a struggle with

European princes and kings to grab as much of this new wealth and power

as possible.

-

Many of the Europeans

were discontent, even disgusted, with this new focus on the offerings of

material culture. Certainly Waldo and Francis were part of this spirit.

-

The monasteries,

as places of retreat from the world, began to attract such people in large

numbers. Many of the monks (men) and nuns (women) in these monasteries

not only devoted themselves to a life of prayer but also to the writing

of hymns and the painting of religious art, focused on the bliss of life

in relationship with God and the heavenly saints. A rich culture

of a Christian "inner spirit" began to grow up in some of the monasteries

in competition with the new secular culture of wealth and power of the

larger Church. Christians who took up this life of the inner spirit

were eventually called "mystics."

-

The Church tolerated,

even encouraged, Christian mysticism--as long as it stayed roughly within

the bounds of traditional Church teachings and as long as it continued

to discipline itself under Roman or Catholic authority.

What was Christian

scholasticism?

-

The Church felt

that it had to bring under its own religious discipline the waking mind

of the West. In the 1100s and 1200s, new schools were being built

in connection with the cathedrals of the many newly wealthy European bishops.

These schools began to offer instruction to talented young minds who were

willing to offer their intellectual service to the bishops.

-

Scholars and "doctors"

of the church were attracted to these schools to offer this instruction

in an ever-widening field of study that included not only theology but

also astronomy, medicine, mathematics and physics. So broad was the

scope of instruction and learning that these schools were eventually called

"universities."

-

In

the early 1200s a Spanish monk of the Augustinian Order, Dominic

de Guzman, proposed to the Pope the creation of a new teaching order, the

Order of Preaching Brothers (later simply called the "Dominicans").

When the Dominicans proved their zeal in hunting down heretic Cathars and

Waldensians, the Popes extended to them ever greater authority to "teach"

the European hearts. Not only did the Dominicans open schools around

Europe, they became leading scholars in the new universities. (They

also later became the directors of the Inquisition, whose job was to hunt

down and eradicate "heretics" within the Christian world.) In

the early 1200s a Spanish monk of the Augustinian Order, Dominic

de Guzman, proposed to the Pope the creation of a new teaching order, the

Order of Preaching Brothers (later simply called the "Dominicans").

When the Dominicans proved their zeal in hunting down heretic Cathars and

Waldensians, the Popes extended to them ever greater authority to "teach"

the European hearts. Not only did the Dominicans open schools around

Europe, they became leading scholars in the new universities. (They

also later became the directors of the Inquisition, whose job was to hunt

down and eradicate "heretics" within the Christian world.) -

By

the late 1200s the University of Paris was attracting key scholars to its

work--the most famous of whom was the Dominican scholar

Thomas Aquinas. By

the late 1200s the University of Paris was attracting key scholars to its

work--the most famous of whom was the Dominican scholar

Thomas Aquinas. -

What Aquinas and

other scholars or "scholastics" were attempting to do was to bring all

learning under a single system of knowledge, one presumably that the Church

could then control. They considered every known fact and debated

and debated where and how such facts could fit into the larger system.

They studied the ancient Greek philosophy of Plato and Aristotle (300 years

before Christ)--but particularly Aristotle because he too had tried to

organize all knowledge under a single system of learning.

-

For about a century

such scholasticism swept the universities of Paris, Oxford, Padua, etc.

as university scholars tried to bring all knowledge, all the "facts" of

the universe under human control (and thus the control of the Church).

-

But by the early

1300s scholasticism was being challenged by independent thinkers such as

the Franciscans, Duns Scotus and

William of Occam.

They showed that "fact" was indeed only how the human mind organized the

details of life--and that fact had no permanent existence but changed from

human observer to human observer, depending on a person's feelings or perspective

on things. They also reminded everyone that our knowledge of the

greatest thing of all, God, came to us not as a fact of the mind but as

the reward of simple faith.

-

This anti-scholasticism

of the Franciscans was to have two effects:

-

1) to get the

European mind (briefly) off the idea of organizing all knowledge as "fact"

and

-

2) to separate

the faith of the heart from the study of the "facts" of the world around

us.

-

This gave Western

science a bit of an opportunity to grow up without having having constantly

to answer to theology--although it would still take some time (a couple

of more centuries) before the Church would let up enough on scientists

to allow them to do their research without the fear of being branded as

"heretics."

Why were John

Wycliff and Jan Huss persecuted?

-

There was always

a very narrow limit, of course, as to how much the Church was willing to

tolerate concerning the criticism by some people of its obvious hunger

for wealth and power.

-

At Oxford university,

John Wycliff by 1370 stirred up controversy in teaching the personal

freedom of the individual believer, who stood in matters of faith

accountable only to God--and to no one else. Wycliff also pointed

out that many of the practices of the church not only had no support from

scripture but indeed went against what scripture clearly taught about the

Christian life. To demonstrate his point he translated the Latin

Bible into English so that the common Englishman could read for himself

what it was that God and Christ had once taught the world.

-

Soon his teachings

not only had stirred up Oxford University but were spreading to the universities

on the continent.

-

The Church was

furious about his challenge to its unquestioned authority--but seemed unable

to do anything about them until after his death in 1384, when he was finally

branded as a heretic and attempts were made to have his English Bibles

destroyed. The Church also made it illegal to translate the Bible

from the Latin into the language of the people, claiming that only the

clergy were sufficiently well trained to be able to interpret "correctly"

what scripture taught (meaning, whatever was convenient for the power and

authority of the Church).

-

In

the early 1400s, in Bohemia, John or Jan Huss picked up on Wycliff's

teachings and began presenting pretty much the same ideas at the University

of Prague. He too translated the Latin Bible into the language of

his people, Czech--knowing full well of the danger he was running by doing

so. In

the early 1400s, in Bohemia, John or Jan Huss picked up on Wycliff's

teachings and began presenting pretty much the same ideas at the University

of Prague. He too translated the Latin Bible into the language of

his people, Czech--knowing full well of the danger he was running by doing

so. -

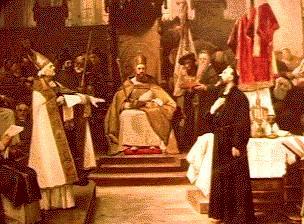

This was very

bad timing because the Church was already in a state of major turmoil--the

politics of the time having produced three different people claiming to

be the true Pope. A number of Church councils were called in order

to try to straighten out the miserable mess the Church was in. One

of these Councils, the Council of Constance also decided to call Huss to

present himself in order to explain why he had been disobeying the Church.

-

Although he was

promised that he could come and go at Constance without harm, Huss was

soon arrested after his arrival in 1415 and burned at the stake as a heretic.

Bohemia immediately exploded in anger. The Church tried to put down

the riots with force--and then with a promise of compromise, offering the

people more opportunity to learn the faith on their own.

-

But the Church

soon put their promises aside, using as an excuse the need for total unity

behind the Church in its response to the military threat of the Muslim

Turks on the Eastern borderlands of Christian Europe.

Who

was Savonarola?

-

Italy in the 1400s

was becoming very, very wealthy. Trade between Northern Europe and

the Muslim East, which passed through Italy, had made many Italian individuals

and even cities very wealthy. Venice, Milan, Pisa, Siena, Florence

and Rome had come to take on the wealthy look that had once belonged only

to the cities of Islam. It looked as if a "rebirth" or "Renaissance"

of the wealth and power of ancient Rome had taken place.

-

This look of wealth

had also come to the Church, which had also grown fantastically rich in

land, servants, churches, monasteries and schools. The Church even

owned whole cities in Europe.

-

In Florence, perhaps

the wealthiest of all Italian Renaissance cities, a Dominican monk named

Girolamo Savonarola had during the late 1400s turned the city upside

down with his preaching which denounced the wealth of the Florentine commercial

aristocracy (which included many bishops in the Church) and the poverty

of the common people. As Savonarola's popularity with the common

people grew greater so did the hatred of the rich and powerful of the city.

But when Savonarola proved to be just as forceful in insisting on the cleaning

up of the morals of the common people, he lost their support. He

was finally hanged in 1498.

What was the

mood like in the Church as the 1500s loomed into view?

-

The Church was

under attack for its corruption in wealth and power. But it seemed

unable to do anything to clean up its own act.

-

The Church always

proved to be outraged when any criticism was directed its way. It

insisted that it alone had the right to determine what was right and what

was wrong--since it alone was the the Bride of Christ and the Popes alone

were the vicars (caretakers) of God on earth.

-

Not only was the

Church insensitive to moral questioning, its own behavior at times was

shocking. Some of the popes were cruel, morally sick, and ambitious

for wealth and power without limit. They used the wealth of the church

to play their political games with the newly wealthy and newly rising princes

and kings of Europe--dragging the church into the most sordid experience

of power politics.

-

In short, by the

early 1500s, the Church was ripe for a sweeping movement of reform, from

top to bottom, from coast to coast.

|

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges