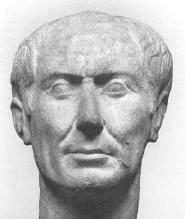

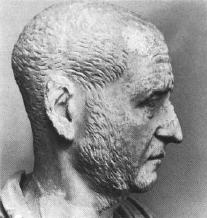

Gaius

Julius Caesar Gaius

Julius Caesar

ca. 100-44 BC.

Julius

Caesar's War Commentaries: Julius

Caesar's War Commentaries:

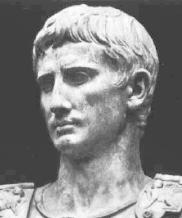

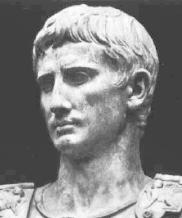

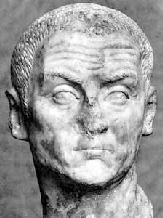

Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD) Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD)

63 BC - 14 AD. Emperor, 27 BC

- 14 AD.

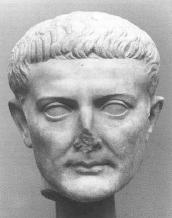

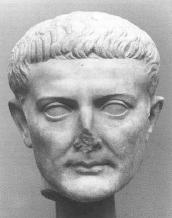

Tiberius

(14-37 AD) Tiberius

(14-37 AD)

A capable administrator – but one who

in the public view became increasingly tyrannical.

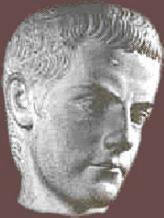

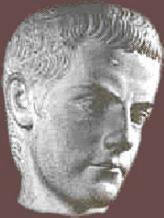

Caligula

(Gaius) (37-41 AD) Caligula

(Gaius) (37-41 AD)

A wastrel ruled by his grand lusts – which

over time turned into true insanity.

Claudius (41-54

AD)

Uncle of Caligula who basically continued

to move the Empire toward the vision that had once directed the actions

of Augustus. He strengthened the Imperial bureaucracy. He completed

the incorporation of client-states into the direct rule of the empire.

He succeeded in bringing southern Britain under Roman rule. But he

lacked polish and was the object of ridicule for his personal ways.

Nero

(54-68 AD)

A wild schemer whose grandiose plans

for the rebuilding of the city of Rome produced incredible tragedy, including

the burning of sections of Rome – which he blamed on the Christian community

(he proceeded to persecute Christians to make good his claims that they

were the ones at fault for the event).

A Period of Confusion

(68-70 AD)

When Nero died there was a rather thorough

murder of the last of the successors to the Julio-Claudian line of emperors.

This in turn produced a civil war which was decided not by Roman political

leadership but by the might of the contending Roman armies. After

a two-year struggle among a number of major contenders, Vespasian emerged

as the remaining candidate for the imperial title.

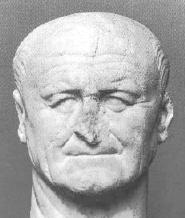

Vespasian

(70-79 AD) Vespasian

(70-79 AD)

9-79 AD. Lacking any special family ties or

noble line Vespasian attempted to undergird his hold over the principate

by assuming for himself the title of Caesar. Thus the term

Caesar

now referred not to the Italian family that had once ruled the Roman principate – but

was transformed during Vespasian's rule into a political title or office.

Caesar

now was a title of special imperial authority.

His rule was further undergirded

by strengthening the move started under Augustus to recommend to the Romans

(especially those with Eastern roots where emperor-worship had a natural

history) special reverence for the imperial caesar – to view the

princeps as a ruler with special sacred authority within the empire.

The last year of his rule marked

the beginning of the conquest of northern Britain (under General Agricola):

78-84.

Titus (79-81)

Son of Vespasian. Famed

for his conquest of Judea and the destruction of the Jewish temple there

in AD 70 – during his father's reign.

Domitian (81-96

AD)

Second son of Vespasian. He was

considered by the Senate a true tyrant. Murdered. End of the

brief Vespasian line of emperors.

Nerva (96-98)

Trajan

(98-117)

He conquered Dacia across the Danube

in modern Transylvania (Romania) bringing it under direct rule in the Empire

in 106. Active in Syria and Palestine – and the Arabian desert to

the East of both. He extended Roman rule to portions of Parthia,

creating the provinces of Armenia, Mesopotamia and Assyria. This

was the furthest extent that the Roman empire would reach – before its territorial

decline.

Hadrian

(117-138)

Hadrian gave up much of Trajan's territorial

gains, including the new provinces in Asia. He focused Roman efforts

instead on consolidating the Roman empire. He built a series of walls

and fortifications delimiting (the limes) the Empire. This

marked the end of Roman expansion and the beginning of the defense

of the Roman empire.

Antoninus Pius

(138-161)

Marcus

Aurelius (161-180) Marcus

Aurelius (161-180)

Marcus

Aurelius' major works or writings:

Meditations

(167 AD) Marcus

Aurelius' major works or writings:

Meditations

(167 AD)

Commodus

(180-192)

Son of Marcus Aurelius. A vain

emperor who fancied himself something of a gladiator and a warrior (leading

the slaughter of helpless animals in Roman arenas and fighting gladiators

who were willing to play along with his charade as long as no one got seriously

hurt). He allowed the imperial office to degenerate into a weak institution

which offered the empire no direction or inspiration.

Another Period

of Confusion (192-193)

Pertinax (126-193) was chosen emperor

but was murdered soon thereafter by the Praetorian guard. They in

turn offered the imperial position to Didius Julian (133-193). But

he was overthrown and executed by Septimus Severus when the soldiers of

the latter marched on Rome and proclaimed him emperor in 193.

Septimus

Severus (193-211)

146-211. Begins the period of

rule by soldier-emperors – in which the imperial title is determined by

a power struggle among Roman generals and their armies. He was the

most able of the lot. He did not seek confirmation of his rule from

the Senate – and in fact ignored that body during his tenure. The

Roman army was devoted entirely to himself and his family. But constantly

challenged by contenders, draining off Roman energies in power struggles

for the imperial position.

Caracalla (Antoninus)

(211-217)

188-217. Oldest son of Septimus

Severus. He murdered his brother Geta in order to secure the imperial

title in 211. The following year he moves to widen the support of

his rule by extending Roman citizenship to most of the free people living

within the Empire.

Elagabalus (or

Heliogabalus) (218-222)

His brief rule ended when he was murdered

by the Praetorian Guard. Indeed he never really succeeded in establishing

his complete rule at any time during his own reign – there being a number

of other quite autonomous claimants to the imperial throne during that

time.

Alexander

Severus (222-235)

Alexander was another son of Septimus

who actually attempted to restore the powers of the Senate. But his

own rule was marked by a weakness which undermined his reforms.

Maximinus Thrax

(235-238)

A Thracian peasant who was brought to

the imperial position by the military. He reversed Alexander's reforms

and restored military rule as the underpinning of the emperorship.

Marks the beginning of a period of decline of the Roman empire as contenders

to the throne vied in combat with each other. This permitted the

Allamanni and Franks to cross beyond the limes of the empire (along the

Rhine) in 236. In 237 the Goths crossed the Danube into the

Balkans at the other end of the Roman line of defence against the Germans.

Yet Another Lengthy Period

of Confusion (238-253)

The confusion of competing would-be

emperors backed by their own armies which started during the reign of Maximinus

only increased in the period after him. During the next 15 years

emperors came and went in rapid succession – with more than one figure claiming

that title at the same time.

Decius

(249-251)

201-251. Decius was one of those

short-lived imperial figures. He was a major persecutor of the Christians.

He ordered a general sacrifice to the emperor to be conducted around the

empire – and for those refusing to do so to be dealt with harshly.

Decius was killed in a battle to

stop the flow of the Goths – who were crossing the Danube at will.

Valerian (253-260)

193-260. He also ordered a massive round

of persecution of Christians.

As the Romans were pushed to the

defensive against the German onslaught against the Empire in the North,

the Persians were undergoing a revival of power under the new Sassanid

dynasty and began to pose a major threat to Roman power in the East.

The Sassanids laid claim to all the Asian provinces of Rome, and attacked

Antioch. In 259, Valerian, trying to organize a defense, was captured

in this battle. In 260 the Persians succeeded in capturing Antioch.

Valerian died in captivity in that same year.

Gallienus

(260-268)

Son of Valerian. During his rule

the chaos descending on Rome reached a peak. The Roman districts

in Germany beyond the Rhine were lost, never to be recovered. A Gothic

navy of 500 ships harrassed Asia Minor and even Greece itself – sacking

Athens, Corinth and Sparta. Roman legions had to operate pretty much

on their own because of the lack of power at the Roman political center.

Cassianius Latinius Postumus (259-269)

M. Cassianius Latinius Postumus was

not an emperor but a local Roman ruler during the chaotic reign of Gallienus.

Backed by the Roman legions of Gaul, Spain and Britain, he established

a provincial empire of his own in the West (Gaul). The regionalization

of power permitted the restoration in Gaul of security from the attacks

of the invading Germans.

Odaenathus ( -266)

Not an emperor – but another regional

Roman ruler during the reign of Gallienus. As governor of the East,

he drove the Persians from Asia Minor and Syria, even recovering Mesopotamia

for Rome. He ruled – as a sovereign by his own right as Prince of

Palmyra – Syria, Arabia, Armenia, Cappadocia and Cilicia. He was murdered

in 266.

Septimia Zenobia

(266-273)

Though the rulership of Odaenathus formally

went to his young son, Vaballathus, in fact it was his wife, Septimia Zenobia,

who ruled after him. She extended her rule into Egypt – and declared

the independence of Palmyran rule from Roman authority.

Aurelian (270-275)

212-275. Aurelian restored central

Roman authority, destroying Palmyran rule in 273 and bringing Zenobia to

Rome in chains. In 274 he brought an end to the independent Gallic

empire in the West, bringing Gaul back under direct Roman rule. He

rebuilt the defenses along the Danube. He even built fortifucations

around the imperial city of Rome itself – a sign of the trouble of the times.

In 275 he was assassinated by some

of his officers.

Probus (276-282)

Defeated the Franks and Alemanni and

secured the Rhine defenses again.

Carus (282-283)

In 282 Carus restored Armenia and Mesopotamia

to Roman rule and reestablished the old boundaries of Septimus Severus.

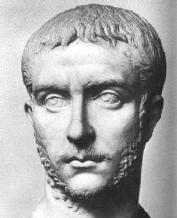

Diocletian

(284-305) Diocletian

(284-305)

235-313. Diocletian attempted

a number of reforms designed to strengthen the greatly weakened Empire.

He divided the Empire into two parts: Eastern and Western.

The Eastern part comprising Asia Minor and Egypt he himself ruled directly

from his capital in Nicomedia. The Western part comprising Italy

and Africa he assigned in 286 to Maximinian, "co-Augustus" with himself,

who was to rule from Milan.

In 293 he chose Galerius as his successor

as Caesar and Maximinian chose Constantius as his successor – freeing

themselves to their work as supreme princips or

Augusti. Thus

a quadripartite rule was established.

In 303, deeply worried about the

rising influence of the Christians in the Empire, Diocletian ordered a

major round of persecution against the Christians in his eastern territories.

This lasted through the rest of his reign – indeed until 313

In 305 both Diocletian and Maximinian

abdicated their rule, leaving power to Galerius and Constantius.

Diocletian retired to his huge villa at Salona (Split) in modern Croatia

and lived out the rest of his 8 years there.

Maximian (286-305)

Constantius I

Chlorus (305-311)

Joint rule with

Galerius : 305-311

Galerius (305-311)

Joint rule with

Constantius I Chlorus: 305-311.

Licinius (308-324)

Licinius was an Illyrian peasant who

rose through the ranks of the Roman Army – and in 308 was named "Augustus"

(junior ruler) by Galerius. In 311, with the death of Galerius, he

received Galerius's political holdings in the West. Two years later

he defeated in battle the Emperor of the East, Maximinius, and took his

holdings.

But Constantine had also been building

his strength as "Augustus" and despite their earlier friendship (Licinius

was even married to Constantine's half-sister Constantia) Constantine forced

Licinius to give up lands to him. Finally in 324 the two met in battle

and Licinius was stripped of his powers. The following year he was

executed on charges of conspiring against Constantine.

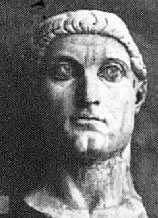

Constantine

the Great (311-337) Constantine

the Great (311-337)

273-337. Constantine was a Roman

Emperor ruling jointly with Licinius from 311 to 324 and solely thereafter

until his death in 336.

We remember him most importantly

for his conversion to Christianity in 312, which opened the way for the

adoption of Christianity as the official religion of Rome, and for his

establishing in 330 a new Roman capital in the East at Byzantium, just

across from Asia Minor.

He was originally a worshipper of

the Unconquered Sun, a widely popular religion in that time. Interestingly,

even as Constantine came to honor Christ, he retained loyalty to this god,

even establishing the first day of the week as the holy day: "Sun" day.

His conversion to Christianity came

in 312 at the Battle of Milvian Bridge – through a series of miracles and

vows which brought him to faith in Jesus Christ.

Within six months of his conversion

he was asked by the Donatists in North Africa to intervene in their dispute

with "apostate" bishops (ones who had at one point denied their faith under

the pressure of persecution) whose authority the Donatists no longer recognized.

Constantine did intervene – but found in favor of the restored bishops against

the Donatists, and ordered the Donatists to submit to the authority of

these bishops.

He went from there to become increasingly

active in imposing "order" on his new church – seeing this as his imperial

duty to God (as always had been the understanding of the Emperor's responsibility

to the empire: that is, to be the "defender of the faith").

He was responsible for calling the

Council of Nicea (325) to decide the dispute between Alexander, Bishop

of Alexandria and his presbyter, Arius – who had come to espouse a monarchian

or "unitarian" position. The Council itself decided in favor of Alexander – and

outlined the basics of the "Nicene Creed," which stood at the heart of

"Trinitarian" Catholic doctrine.

Though Constantine stood firmly behind

the Council and its decision, he himself remained quite tolerant of the

unitarian Arians – who were widely popular in the East (where the Nicene

"Trinitarian" decision itself was unpopular). Rumors were that he

himself had Arian sympathies – but kept them to himself in order to preserve

the religious unity of his domain.

Triumvirate of

Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans (336-350)

Upon Constantine's death in 337 the

empire was divided up among his three sons. They intrigued and fought against

each other – and others – until in 354 Constantius held position as sole

Roman emperor.

Constantius II

(354-361)

Constantius was a fervent Arian and

intimidated the bishops into an anti-Nicene position. At the same time,

pursuing religious conformity within his empire, he pushed the Christian

cause against paganism more forcefully than his father had – closing the

temples in 356 and removing the alter of Victory from the Roman Senate

in 357.

Julian (361-363)

Called the "Apostate" for his efforts

to end Christianity's religious monopoly and restore pagan worship to prominence

in Rome – even though he himself was raised in his youth as a Christian.

Julian was a nephew of Constantine

who had miraculously escaped the murderous intrigues that took the life

of most of the rest of his family in 337. Upon finally becoming emperor

himself, he disclosed his pagan loyalties and began to try to undo the

work of his Christian uncle Constantine and cousin Constantius. He

tried to substitute a new religion based on Platonism in which the Supreme

Being was identified with the Sun God Helios (akin to the popular Mithras).

He tried also to establish the same moral rigor for his faith that made

Christianity so respectable – and even copied the ecclesiastical organization

of the Christian church.

He did not directly persecute Christianity

but did remove Christianity's privileged position within the government

and forbade Christians from teaching in the public schools (in an effort

to bring the empire back to its pre-Christian traditions through the children).

But there was no real zeal among the populace for his reforms – which became

quickly apparent soon after he took over. This really closed the

book for traditional paganism.

Jovian (364-365)

Valentinian I

(West 364-375)

Western Roman Emperor

Valens (East 364-378)

Eastern Roman Emperor – brother of Valentinian

I.

In 370 Huns poured into Eastern Europe

from Asia, pressing the German-speaking Goths who inhabited the area. Emperor

Valens permitted the Goths (Visigoths or Western Goths) to settle inside

of traditional Roman lands, hoping that they would serve as a buffer to

the Huns. But soon both the Visigoths and their close kinsmen the Ostrogoths

(Eastern Goths) joined forces to defeat the Eastern Roman armies – establishing

Gothic autonomy within the Roman Empire. Eventually many of them were brought

into the Roman army in the hope that they would add vigor to the declining

Roman military power.

Gratian (West

jointly 375-383)

Joint Western Emperor (367-375)

with his father Valentinian until the latter's death in 375 and then with

his 4-year old brother Valentinian II.

The Empire was under constant attack

from Germanic tribes and he spent his rule mostly in Gaul fighting off

the Goths.

In 383 he marched his army against

the usurper of Roman power in Britain, Magnus Maximus. But his tooops

deserted him and he was murdered during his attempt to escape.

Valentinian

II (West jointly 375-383; solely 383-392)

Emperor of the West: jointly with

Gratian from 375 to 383 and solely thereafter until 392.

Theodosius I (East

379-392; East and West 392-395)

346?-395. Eastern Roman Emperor

from 379 to 392. After 392 until 395 he ruled both East and West.

He called the Christian Council of Constantinople.

Symmachus (345-410)

Quintus Aurelius Symmachus was not a

Roman Emperor – but was however a strong voice of the old pagan viewpoint

in the Roman Senate. His life of public service, his sterling moral

character and his wealth and personal influence made him an outstanding

spokesmen against the Christian ascendancy in Rome. In 382 he was

expelled from Rome after his strong protest over the removal of the statue

and altar to Victory in the Senate chamber. He was restored to influence

soon thereafter (prefect of the city of Rome), but proved to be still as

adamant as ever over this issue, appealing to to Emperor Valentinian to

restore these symbols of traditional Rome.

Stilicho (394-408)

Flavius Stilicho was not a Roman emperor – but

a mighty political force in the Empire that at times exceeded in power

the position of the Western Emperor.

He was born to a German Vandal officer

in the Roman army of emperor Valens. Stilicho himself joined the

imperial army and rose quickly up the ranks. In 383 he was sent by

Emperor Theodosius as a diplomatic envoy to the Persian King Sapor.

On his successful return he was brought into the imperial family by marrying

the Emperor's niece/adopted daughter, Serena.

In 385 he began a very successful

military career: in Thrace against the Goths, in Britain against

the Picts, Scots and Saxons, and along the German Rhine.

In 394, with his wife Serena, he

was appointed regent over the youthful joint emperor, Honorius – bringing

Stilicho into the thick of imperial politics. His main rival to his

deep political ambitions was Rufinus. In order to bring him down

Stilicho marched his army to the east to meet Rufinus, but then had Rufinus

assassinated. This made Stilicho the virtual dictator of the Roman

Empire.

In 396 he was drawn into Greece to

fight Alaric and the Visigoths – but

worked out a diplomatic settlement with Alaric instead.

By the year 400 he was consul – and

also father-in-law to Honorius.

In 401-402 he was called to action

again against Alaric (and Alaric's ally Radagaisus) – this time along the

Danube and in Italy. Once again he was successful in delivering the

Empire from this Barbarian threat through military victory and diplomatic

settlement. But in 405 Radagaisus again invaded Italy. This

time Stilicho starved Radagaisus to defeat.

In 408 Stilicho began to strengthen

his hold over Honorius with the marriage of his second daughter to the

Emperor. But then he was accused of plotting to overthrow his son-in-law

in order to establish himself as Emperor. Whatever the truth of the

matter, Stilicho fled to Italy, taking sanctuary in Ravenna. He was

brought out by a promise of safe-conduct – but was seized and executed nonetheless.

Honorius (394-423)

Emperor of the West, whose political

fortunes during the first 14 years of his rule were closely tied to Stilicho.

Arcadius (395-408)

c. 377-408. Emperor of the East, brother

of Honorius. It was during his reign that Alaric

invaded Greece.

Theodosius II

(East 408-450)

Valentinian

III (West 423-455)

|

Moses

Moses

David

David

Pericles

(490-429 BC)

Pericles

(490-429 BC) Alexander

III (the Great) of Macedonia (356-323 BC)

Alexander

III (the Great) of Macedonia (356-323 BC)

King

Pyrrhus of Epirus

King

Pyrrhus of Epirus Hannibal

Barca ( -182 BC)

Hannibal

Barca ( -182 BC)

Marcus

Tullius Cicero

Marcus

Tullius Cicero Pompey

(82-54 BC)

Pompey

(82-54 BC) Gaius

Julius Caesar

Gaius

Julius Caesar Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD)

Caesar Augustus

(Gaius Octavius) (31 BC - 14 AD)

Vespasian

(70-79 AD)

Vespasian

(70-79 AD)

Diocletian

(284-305)

Diocletian

(284-305) Constantine

the Great (311-337)

Constantine

the Great (311-337)