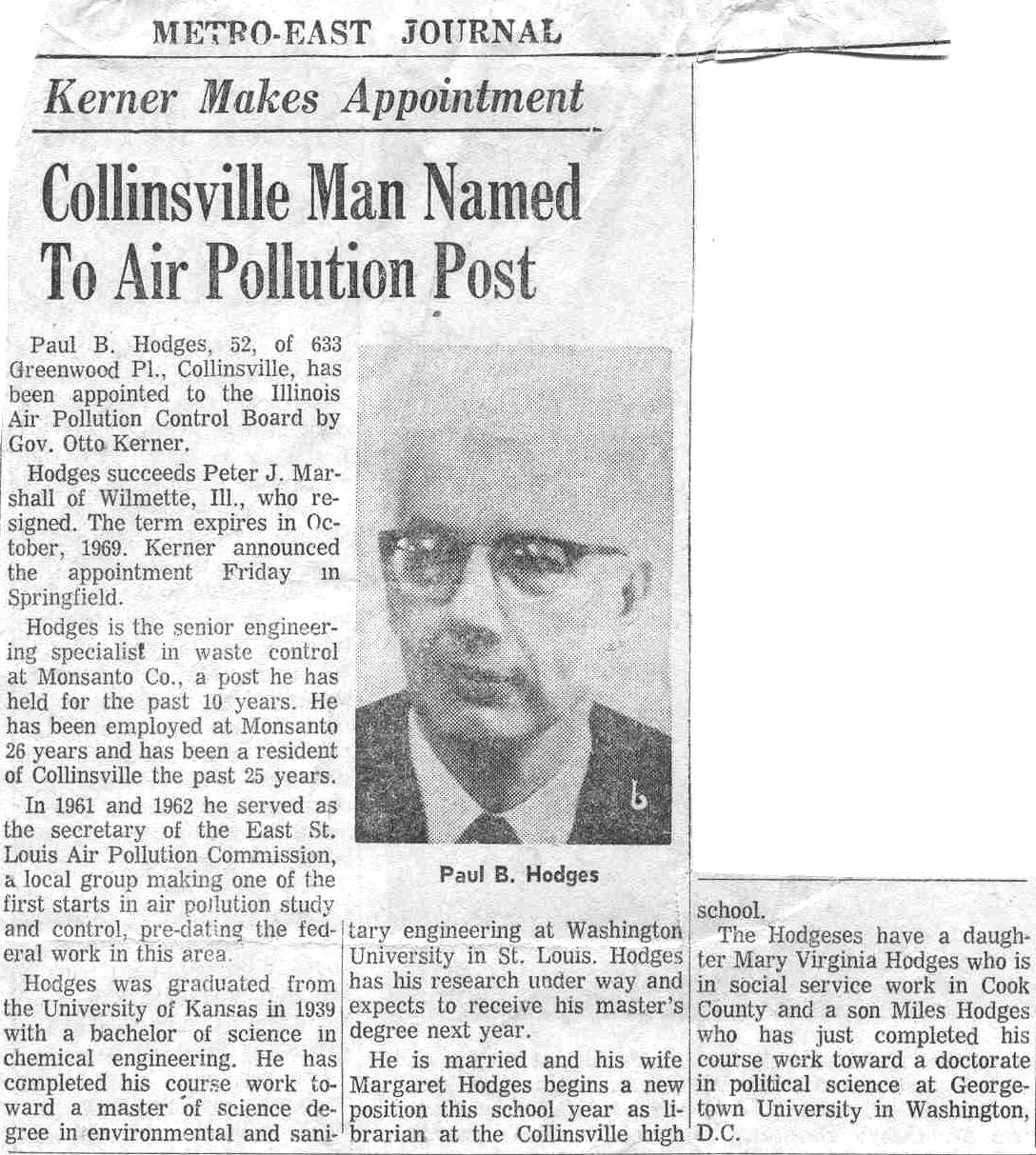

|

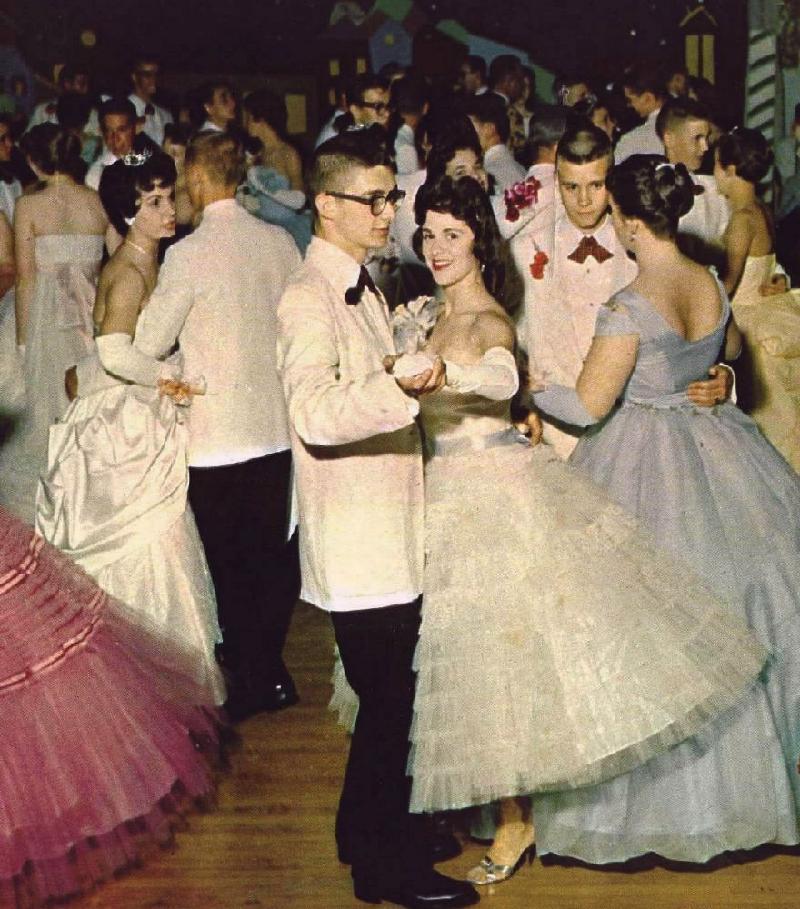

THE EXPATRIATE

LIFE

(1968-1970)

|

|

|

|

Asia – following the trail of Alexander the Great

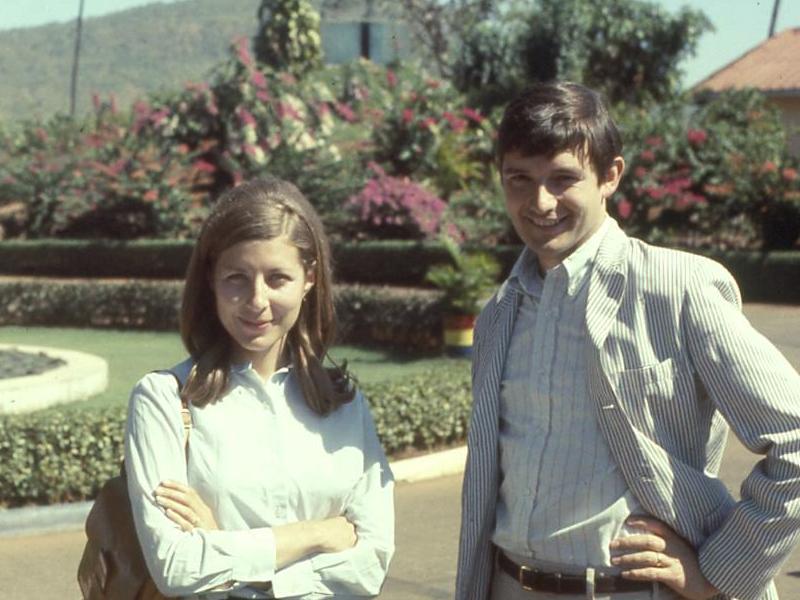

Martha and I bought a used VW "squareback" (station wagon) in Brussels,

Belgium, and then headed east, down through Germany, Switzerland, and

Italy to Greece, then picked up parts of the trail of conquest of

Alexander (300s BC). We crossed Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan –

encountering some of the most incredible driving conditions along the

way, not to mention people and places.

By the most amazing timing, we hit historical sites well beyond the

tourist season, traveling as we were in September, October, November,

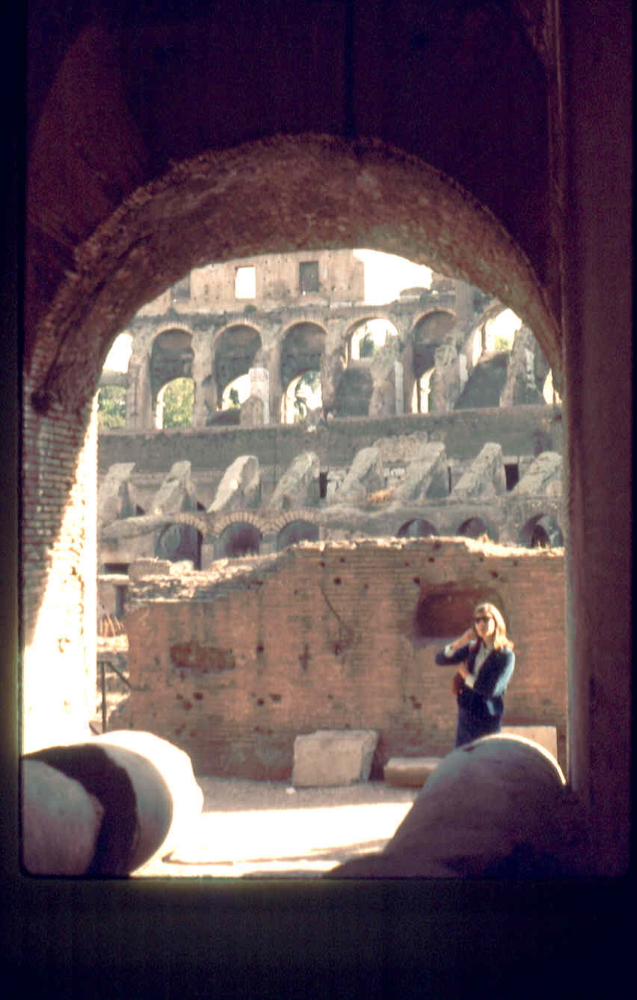

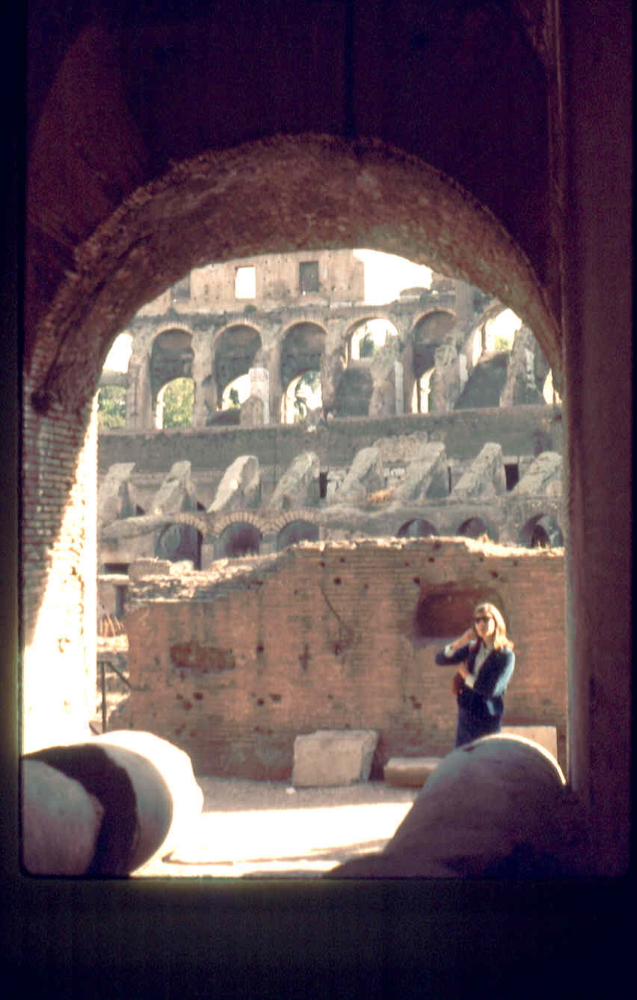

etc. For instance, at the Roman Colosseum, we saw no one else there at

that time; at the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, there seemed to be

only a handful of people touring the place; there were not a lot of

people on Athens' acropolis; we were the only ones at Mycenae, Olympia,

and Sparta (although Sparta was mostly still not excavated at the

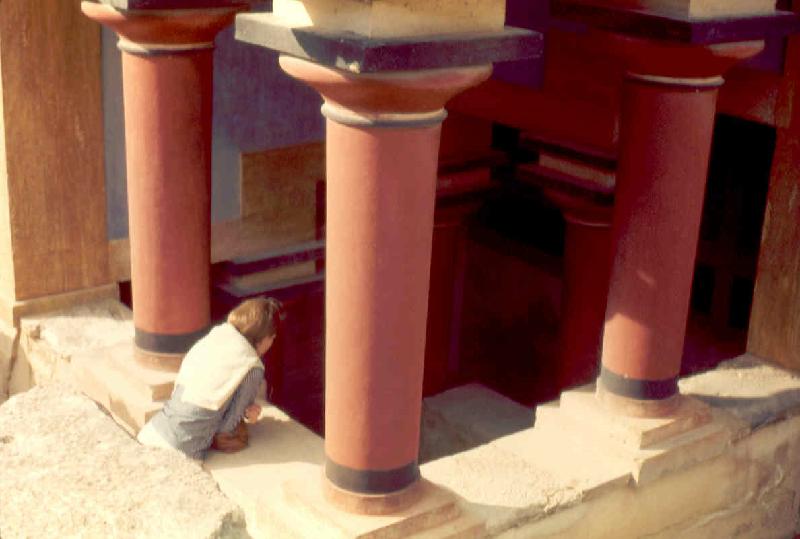

time); we were the only ones at the ancient Cretan capital of Knossos

(on both of our two days visiting there); there was only another two or

three people at the ancient city of Corinth; no one else was at

Alexander's home of Pella or at the ancient Hittite capital at

Boğazkale, and on and on. It was weird and wonderful. But it allowed

us not just to tour the sites, but to sit and reflect on the historical

perspectives that just being there allowed.

|

| We bought a VW

"Squareback" in Belgium, and proceeded to head Southeast, to

Geneva, then Italy, then East across to Greece, then on to Turkey, then Iran,

Afghanistan, Pakistan (leaving the car there and continuing on by train), to India and

finally flying from India to Nepal … arriving in Kathmandu by

Christmas. |

What was so

wonderful was that

it was past the tourist season … and we had famous historical sites

nearly to ourselves. In fact, in most instances, we were the only ones on

site.

The Roman

Forum   The Roman

Colosseum The Roman

Colosseum

The Via Appia

(Roman road) / Pompeii

In Greece: the

ruins of ancient

Sparta and the ancient Stadium of Olympia

Mycenae: The Lion's Gate

and King Agamemnon's

Palace

The ancient

city of Corinth

Athens – Early October (1968) The Parthenon and the

Erechtheion

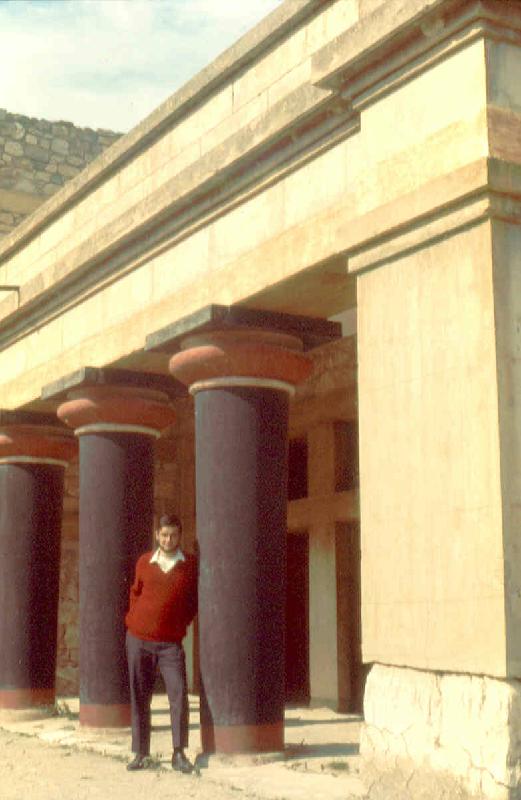

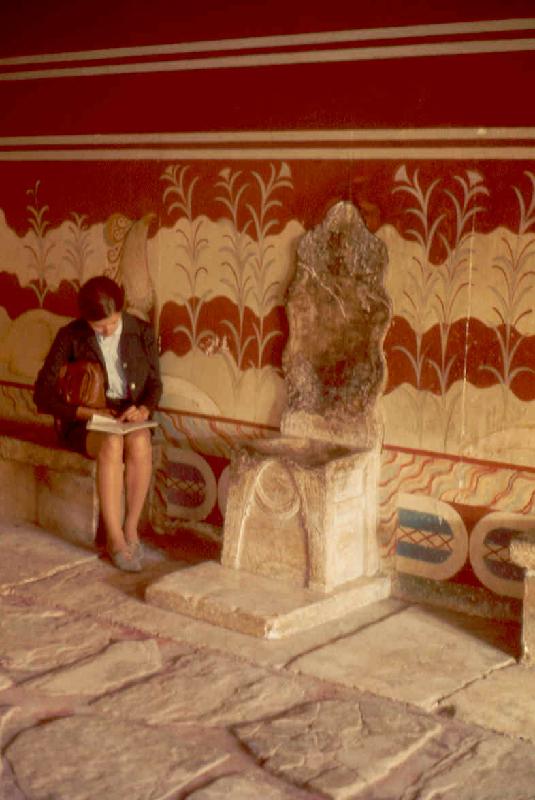

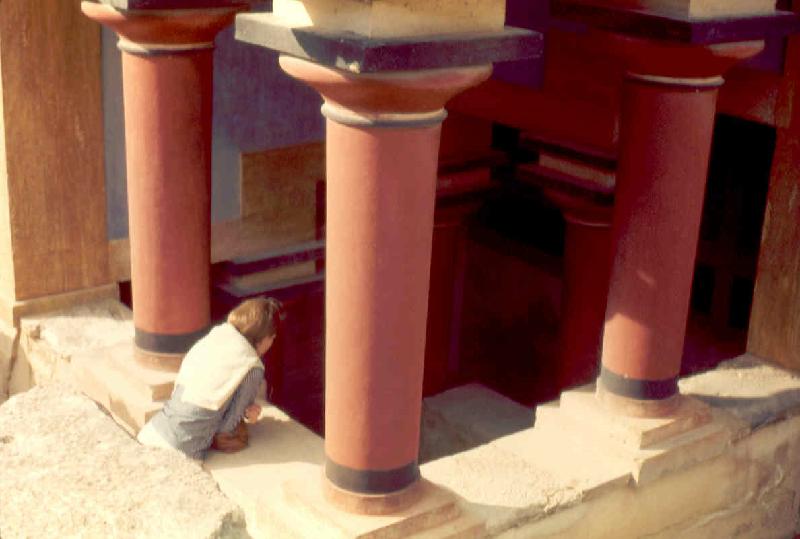

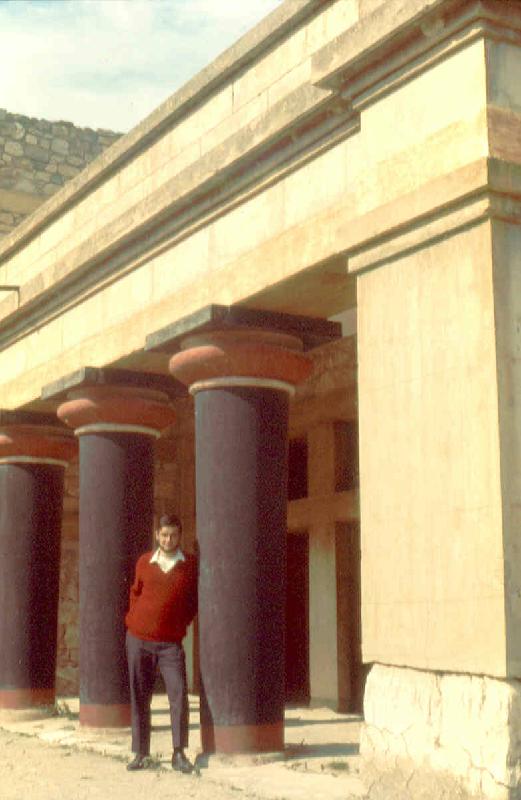

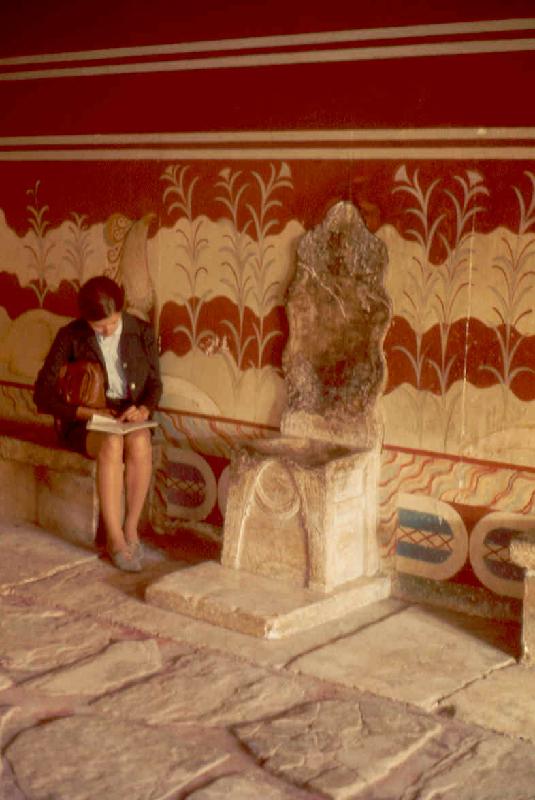

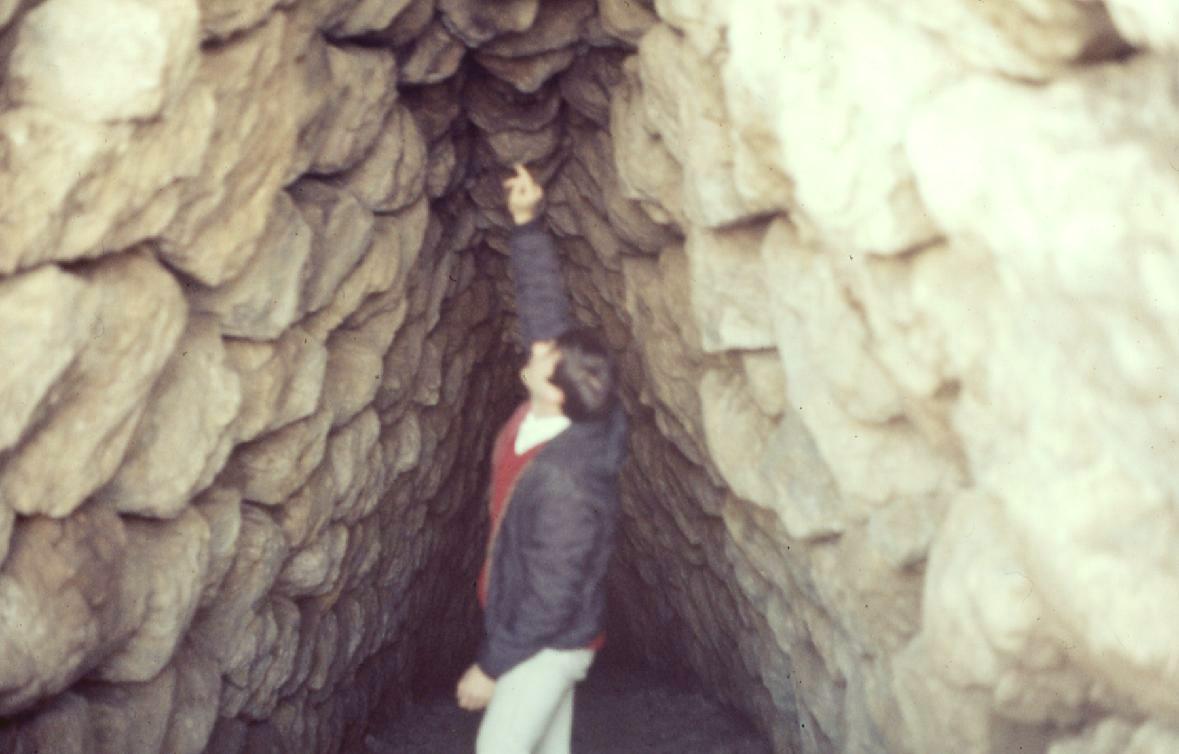

Knossos, the capital of the great Crete civilization / Martha staring down into the

Labyrinth

The king's room and the throne room at Knossos

Alexander's capital at Pella in Macedonia

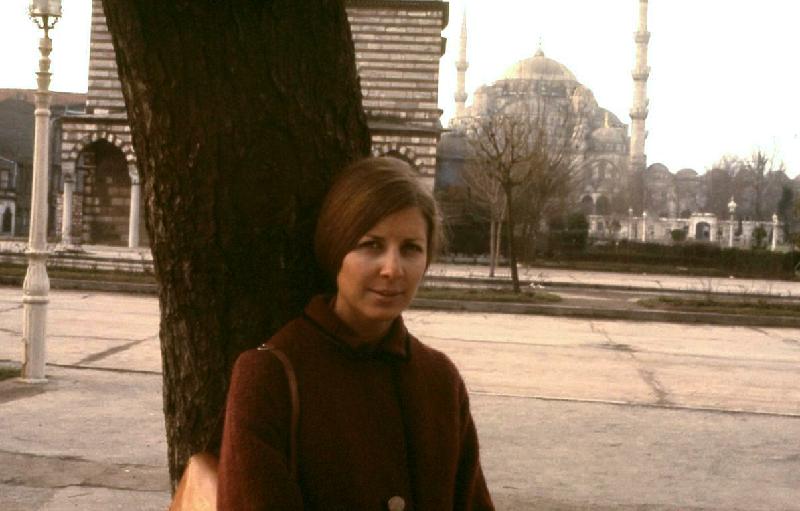

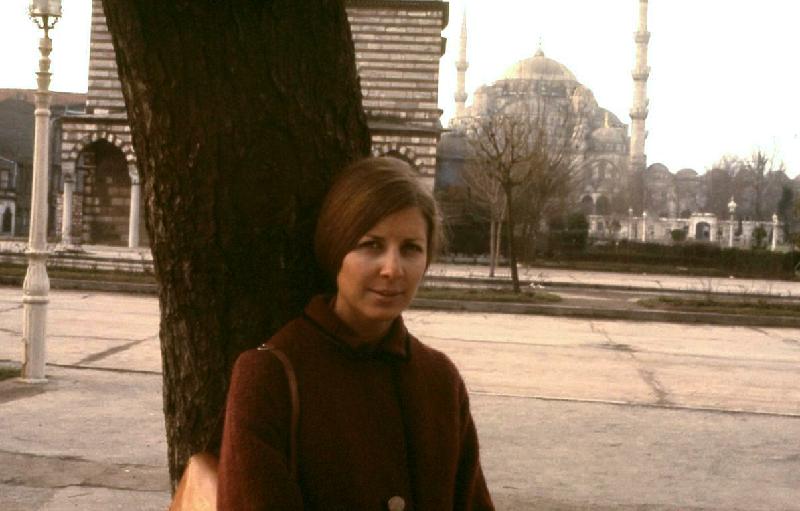

It's November ... and we arrive in Istanbul: The Bosporus and the Hagia

Sophia

Inside the

Hagia Sophia As we

head East from Istanbul through Bithynia, we are most definitely in Asia ... and getting our

first

glimpse of the Asian countryside as it will appear across Turkey,

Iran and Afghanistan. Impressive vistas ... but barren.

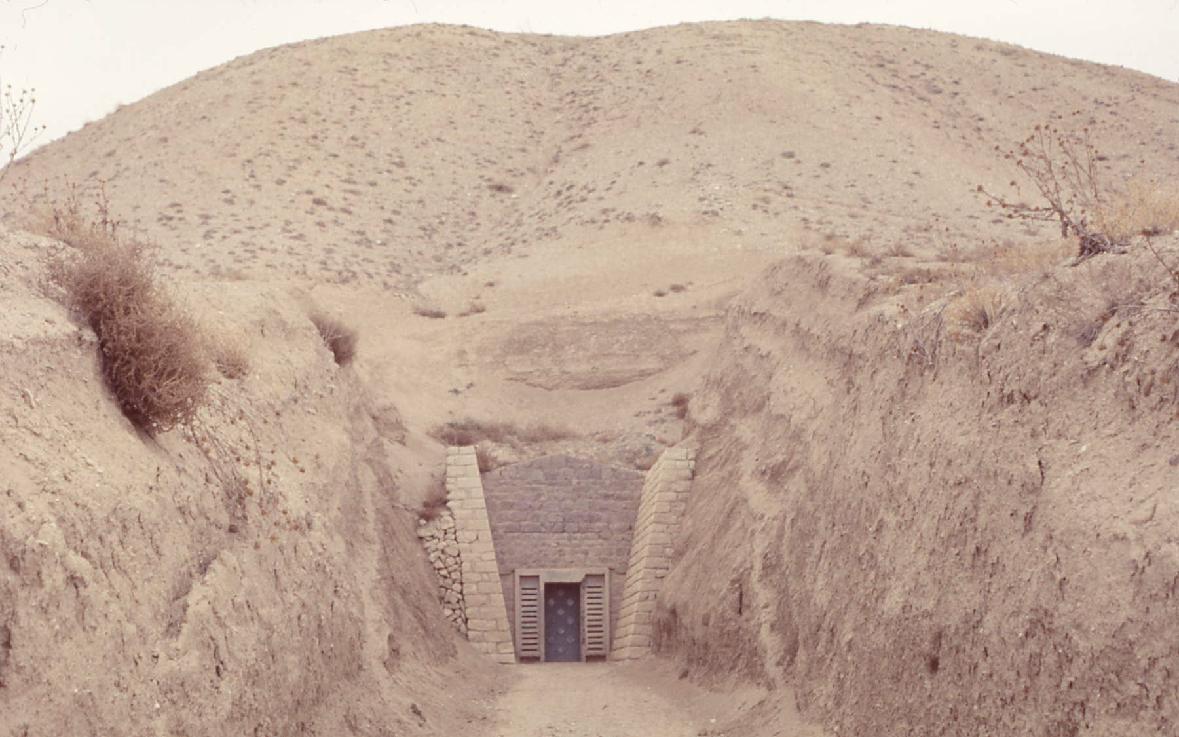

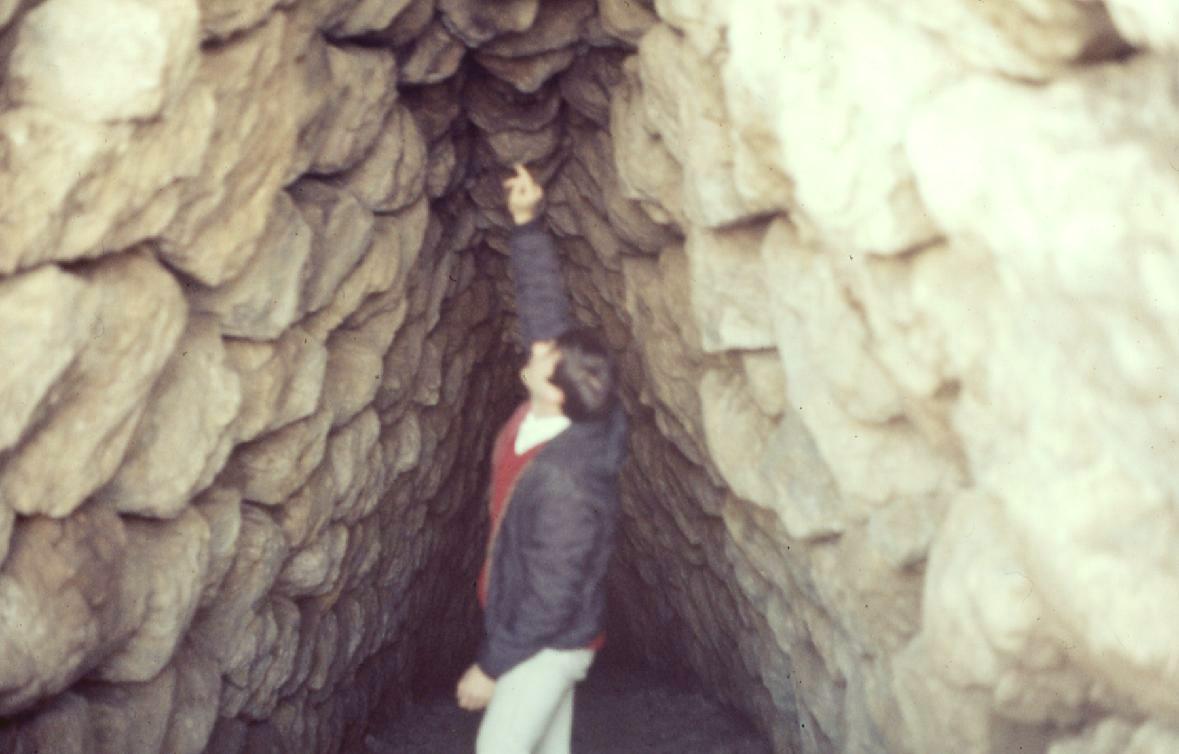

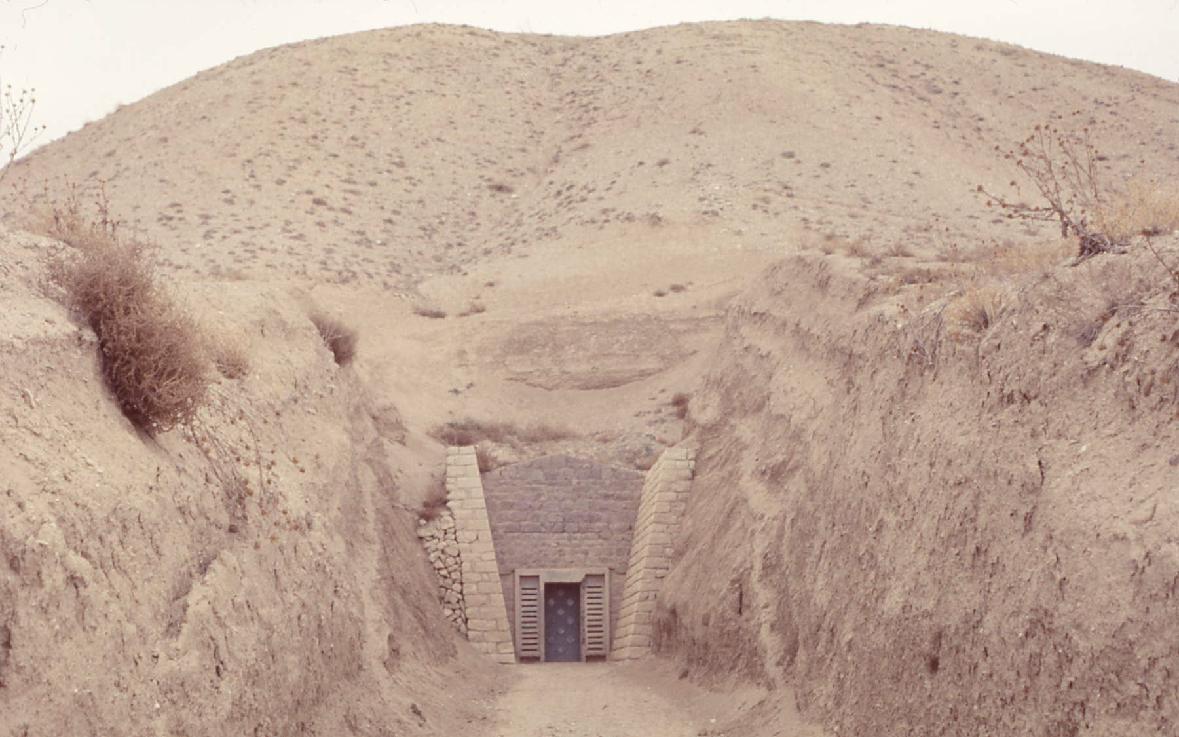

We stop along the way at

Gordian, to visit "Midas's Tomb" (probably not!)

...

and the ruins of the city where Alexander "untied the Gordian Knot"

with his sword ... fulfilling the prophecy that one such as he would

conquer the world. Although Alexander did not conquer the world,

he did conquer a good part of it!

We finally arrive (through massive mud) at Boğazkale … location

of

the

ancient capital of the Hittite Empire (anciently, the city was called Hattusha)

Once again,

we spent the day alone there (noting where a swinging door left its scratches!)

We arrived at the coast of the Black Sea (which most

definitely is not Black!)

... and a very nice road, though a bit crowded here and there!

We then arrived at the beautiful Black Sea

coastal city of Trabzon ... before heading east

... and passing Mount Ararat

along the way (the famed resting place of Noah's Ark)

While

at Trabzon, an American soldier posted at an observation post there

told us a tragic story of how this region known as Turkish Armenia was

cleared of its Armenian population by the "Terrible Turks" during the

early part of the 20th century ... by Turks loading the Armenian men

into boats and dumping them out in the Black Sea ... and then turning

on the women and children ... who suffered all sorts of unmentionable

treatment by the Turks.

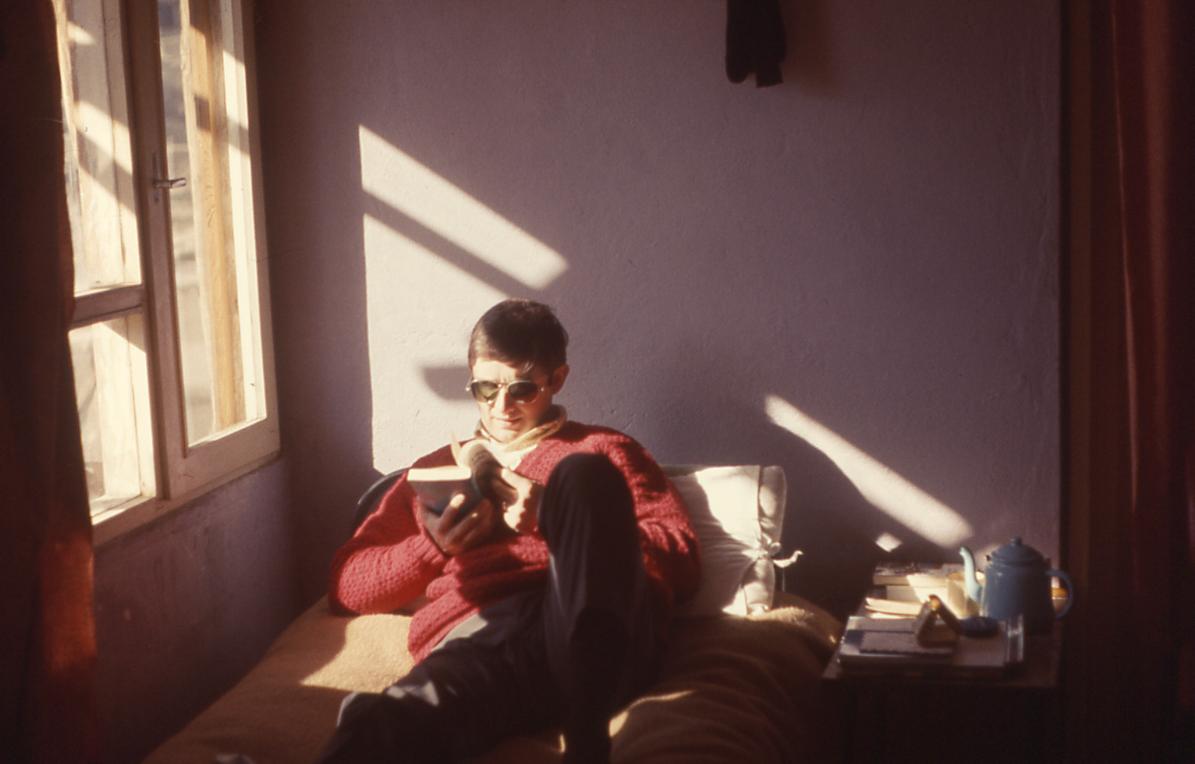

At this point we headed into the Armenian Mountains

... and, as the road

took us higher, we saw some very worrisome snowy conditions ahead. This made me quite nervous,

because I knew that we had to come back

this same way some months later, during

the height of winter. Eventually we came down the other side ... where I had some serious car

cleanup to do!

|

Iran

In Iran's capital of Tehran, we stayed with the family of one of my

former Georgetown housemates, a very pro-Western family. They were able

to explain to us the complexities of the Westernization of a proudly

Muslim (although Shi'ite Muslim rather than Sunni Muslim) society, that

also had not forgotten its origins as the ancient empire of Persia (the

European West's constant enemy). And although where we were located in

Tehran was fully modern, we were warned not to venture into the very

traditional southern part of the city, where the hatred of Westerners

ran deep.

It was at this point that we realized the delicacy of the cultural

situation that America's close ally, the Shah, was dealing with. But

(at the moment) he was generally very popular among his people, even

out in the very conservative countryside. He had brought visible

upgrading to the roads, city centers, schools, etc.

As a consequence, except for certain pockets of the country, we were

well received as Westerners, in particular as Americans, especially

since there seemed to be no others of that category around! Even here,

we seemed to have this venture into the East all to ourselves!

|

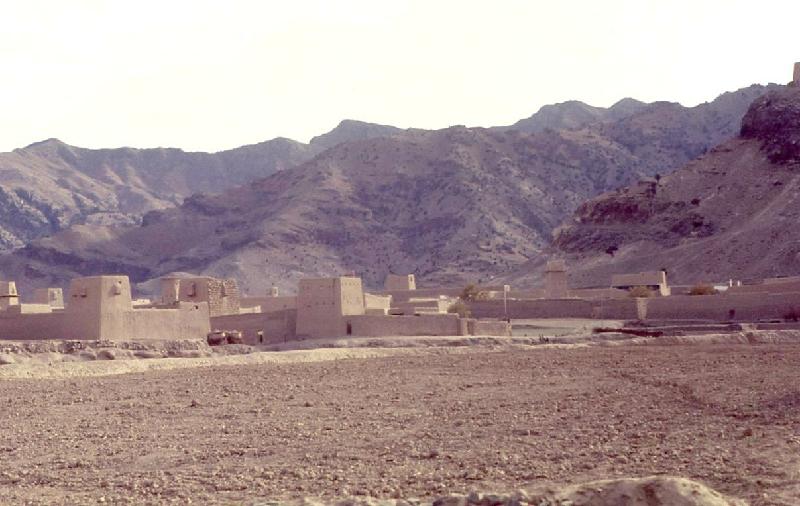

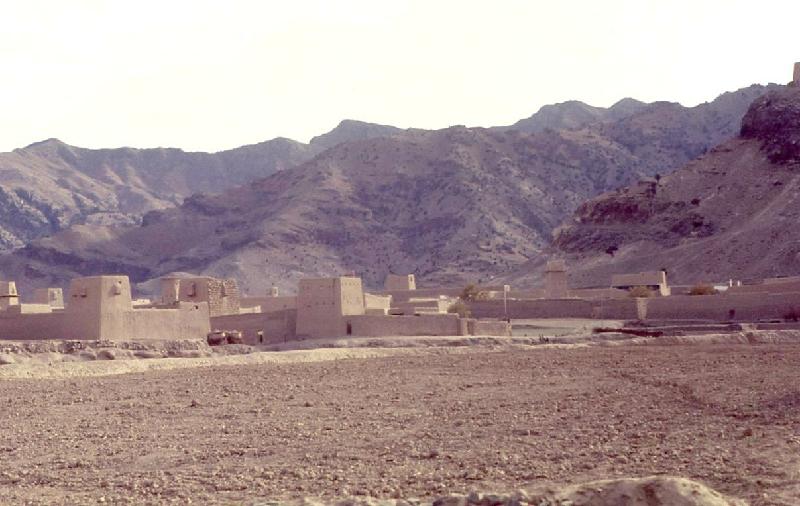

Then

we headed east across northwestern Iran. I would begin to see a

lot of fortified villages ... a reminder of how violent life could be

in that part of the world.

I

realized also the risks Martha and I had embraced in taking on this

trip. I was, of course, always apprehensive ... but never afraid.

Indeed,

what actually kept us going was a strange sense that there was some

"unseen hand" on our

lives ... something I would come to call "fortuna." I had long ago given

up my Sunday School idea of God … but had not (not yet anyway) given up on

the notion that

somehow I enjoyed very peculiar protection. It

allowed

me to do things that held most people back. Years later I would come to understand that this had always

been

the hand of God. Eventually

we arrived at the city of Tabriz in Iranian Azerbaijan ... where a Mr.

Hararichi took us under his wing to show us around ... including a

rug factory where a man was hand-weaving a very fancy (and thus

probably very expensive) Iranian rug.

Then we

headed on to Tehran, Iran’s capital, where we stayed with the family of a former

Iranian Georgetown housemate of mine. We were

surprised to see how modern it was

… at least the northern half of the city (thanks in part to

the modernizing

policies of the Shah). We were told to stay out of the

Southern half of the

city (militantly traditionalist Muslim), because the people there hated

Westerners …

and what Western culture had done to their Muslim world.

Then we

headed north out Tehran, soon reaching the snowy Elburz mountains,

crossed them

and then came down a very steep road on the other side ...

... to the

Caspian Sea ... whose coast resembled greatly the coast of the Black Sea Then

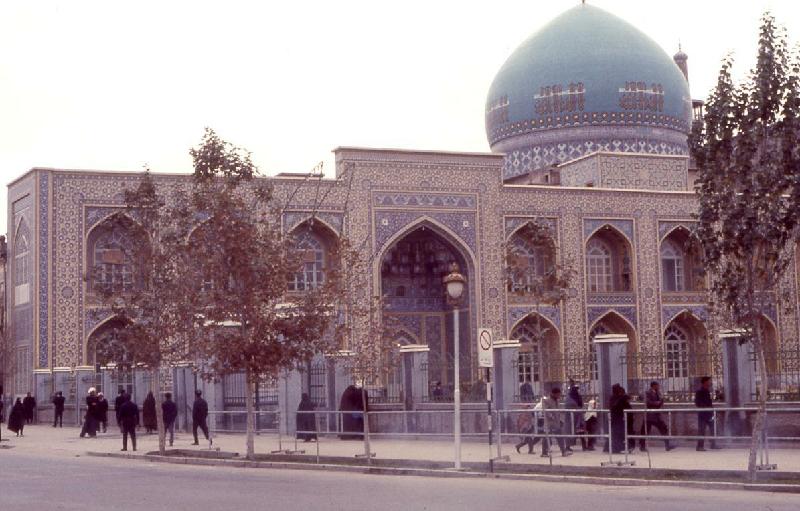

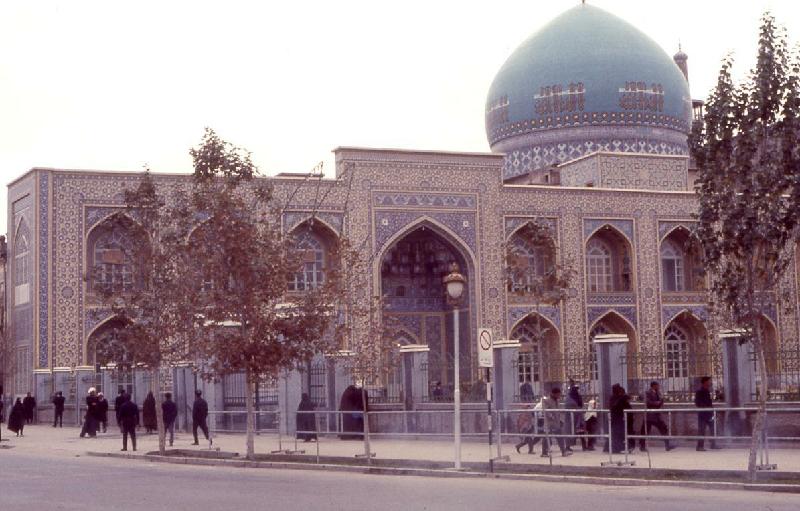

we headed into Eastern Iran ... the bastion of Iranian-Muslim

conservatism. Aware of this sensitivity of traditional Islam … we

continued to move East

cautiously … finally arriving at Mashhad, sort of the headquarters

for this traditionalism.   The very

conservative city, Mashhad ... in Eastern Iran.

Notice the scarcity of women in

public! Martha

was of course "uncovered" ... and we really stood out as strangers!

A group of people took an interest in us when one of them

was able to converse with us at a restaurant. I don't

remember in what language, because French or German were just as likely

as English to be known in this part of the world. Actually the

likelihood of any of those languages being spoken in Mashhad was slight! The remoteness

of Eastern Iran ... as most everywhere in central Asia

At this point our roads grew very challenging!

|

Afghanistan

When we got to the Iran-Afghan border, our car got bogged down in the

mud in the five-mile stretch of no-man's land between the two

countries. We were finally able to get a group of Afghan soldiers sent

to get our car out of its mess. Then we had to spend the night at the

Afghan border sleeping in the car.

Early the next morning we were asked to take on an Afghan traveler, who

had run out of travel funds, had managed to get to the Afghan border –

and needed to get into Herat, where he could then continue on his own.

We were told that he was head of the country's Chamber of Commerce.

Yeah, right – as if we were stupid enough to believe such a fishy

story! But we took him on anyway.

When we got to Herat, we took him to the airport, where he took a

flight onward to Kabul. And indeed, we knew by that time (he spoke

excellent German) that he was indeed what he claimed to be. Before he

departed, he invited us to look him up when we got to Kabul.

The drive the rest of the way across Afghanistan was peaceful and

largely uneventful, almost anyway. It was at one part of the road that

we passed a group of men along the road, waving their hands wildly at

us. We thought that was very friendly, until (at 100 kilometers an

hour) we went sailing into a crude iron pipe poised across the road, to

stop travelers (few of whom were actually on the road) so that they

could collect "passage" money from them. Thankfully the bar merely

creased the upper left portion of the car. Had it been a few inches

lower, it would have taken off my head. As these guys came running up,

I was furious. I pointed out the glass lying about. Obviously, we were

not the first ones to have experienced this misadventure. They shrugged

their shoulders, and we continued on. We would have to have the car

repaired in Kabul.

We were rather shaken by the experience, even though it was not the

first time that strange (and dangerous) things had come our way. Nor

would it be the last of such episodes either.

But after all, we had willingly, gladly actually, undertaken an

adventure that everyone back home thought qualified us as being totally

insane. Where we were going was uncharted territory. And indeed, we

took on each day with no way of knowing how things would turn out for

us that day. But that's just who we were, adventurers.

I mention this particular episode because of how it led to other

amazing things. When we reached Kabul on the other side of the country,

we took a few days to enjoy its interesting primitiveness. And then,

with the car repaired, we found ourselves ready to move on into

Pakistan. But in the meantime, we were advised not to do so just yet,

but to wait until a violent uprising going on just across the border in

Pakistan had a chance to settle down (this area was "Pakistan" only on

the map, but actually a very, very independent-minded Pashtun region).

We took the advice. A British couple we met in Kabul did not, and soon

returned with their car badly damaged and one of them badly bruised and

cut up. We knew we were therefore going to be in Kabul for a while.

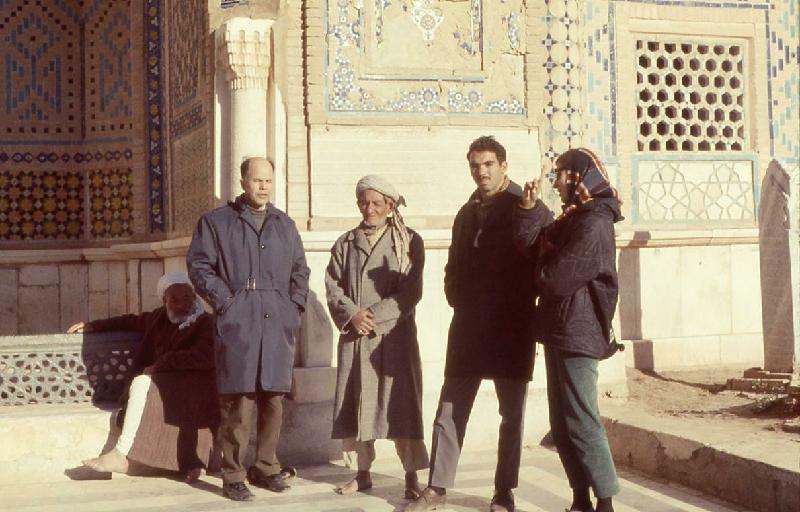

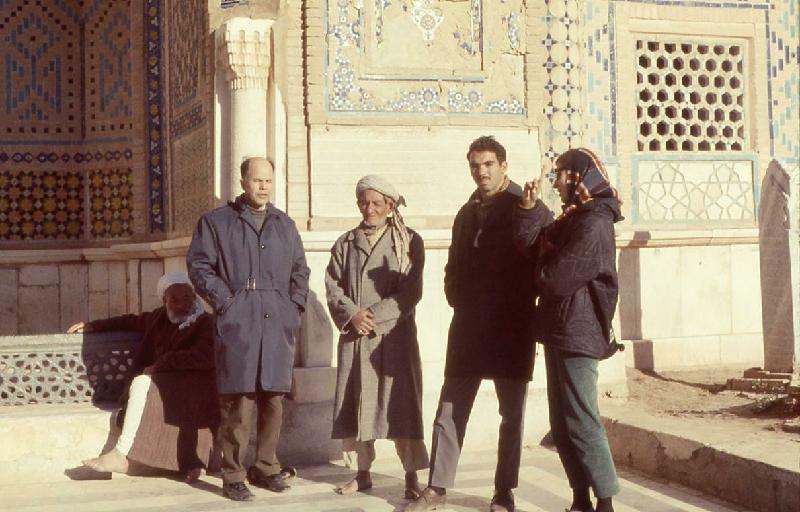

At this point we decided to take up the invitation to visit our Afghan

Chamber of Commerce friend, Muhammad, and sent word to him where we

were staying. Finally, a hotel clerk came to our room to tell us that

someone waited for us in the lobby. But when I went down, all I saw

there was someone who was obviously an Englishman ... by his very dress

and demeanor. But wouldn't you know, it was his nephew, Nasir, who

indeed was an architect, schooled at the University of London and

well-experienced in the field in England itself. We would spend the

next days (a week really) with him, and friends.

Indeed, it was nearing the end of November, and Nasir's brother and

family invited us to their home to help us celebrate our American

Thanksgiving holiday. What a wonderfully gracious family they were. And

it turned out also that he was the country's leading surgeon, who had

trained in the field in Houston under the direction of the famous heart

surgeon, Denton Cooley! Wow!

But the "wow" did not stop there. We even got an invitation to a

fashion show put on by the Afghan Queen, and found ourselves in the

most amazing company in the process.

Even after we moved on, we would keep close contact with our Afghan

friends, for a number of years anyway, when several moves and changes

later in our lives broke the lines of communications. Then when I heard

that Soviet-backed "reformers" had taken over the country in 1978,

producing a civil war that killed thousands, among them numerous

Westernized Afghans, a deep chill hit me. I feared that this statistic

most likely included our once-close Afghan friends.

|

Afghanistan

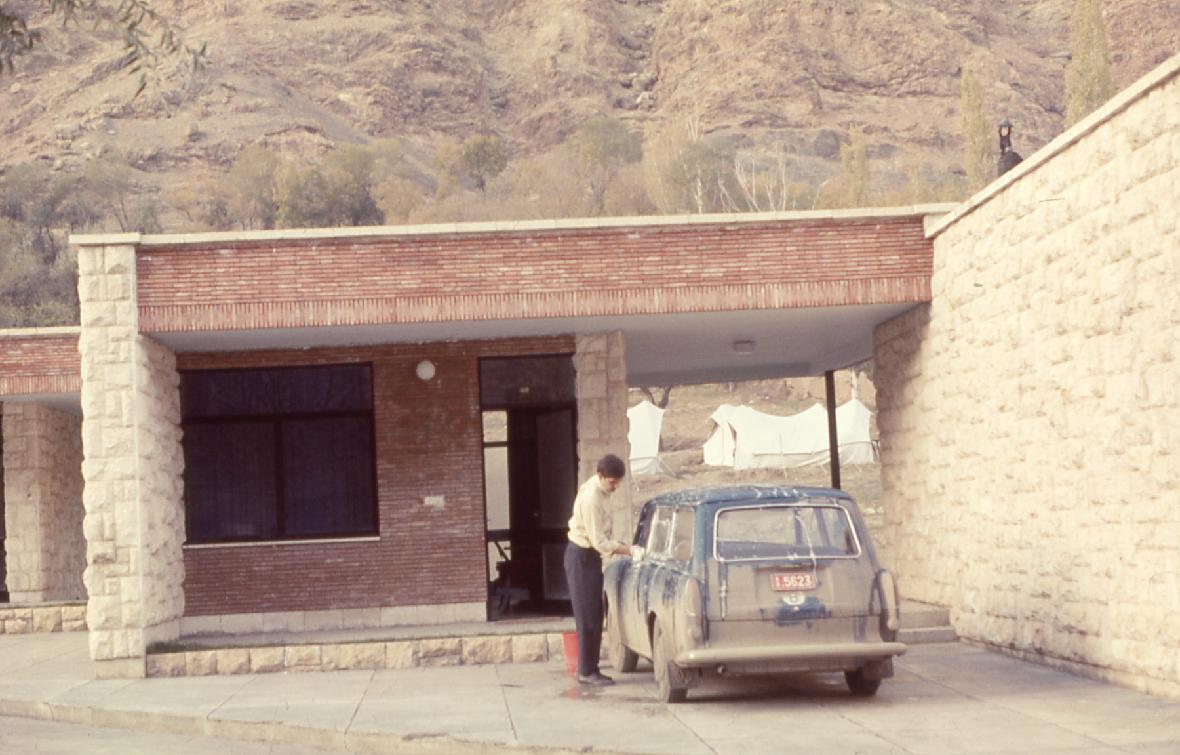

Then

arriving at the Iranian-Afghan border ... we got hopelessly bogged

down along the 3-to-4-mile-long "no-man's-land" between the two

borders.

The next morning we met the president

of the Afghan

Chamber of Commerce, Mohammed Saleh (actually giving him a

ride into Herat) ... and then later enjoying a Thanksgiving meal with his

relatives in Kabul (a surgeon who had trained in Houston and his

family), attending

a reception and dinner put on by Afghan’s king and queen, and

just hanging out with Mohammed's nephew, Nasir (a London-trained architect).

With Mohammed in Herat

In Kabul with Nasir and an Indian musician / Martha decked out in an Afghan

burka!

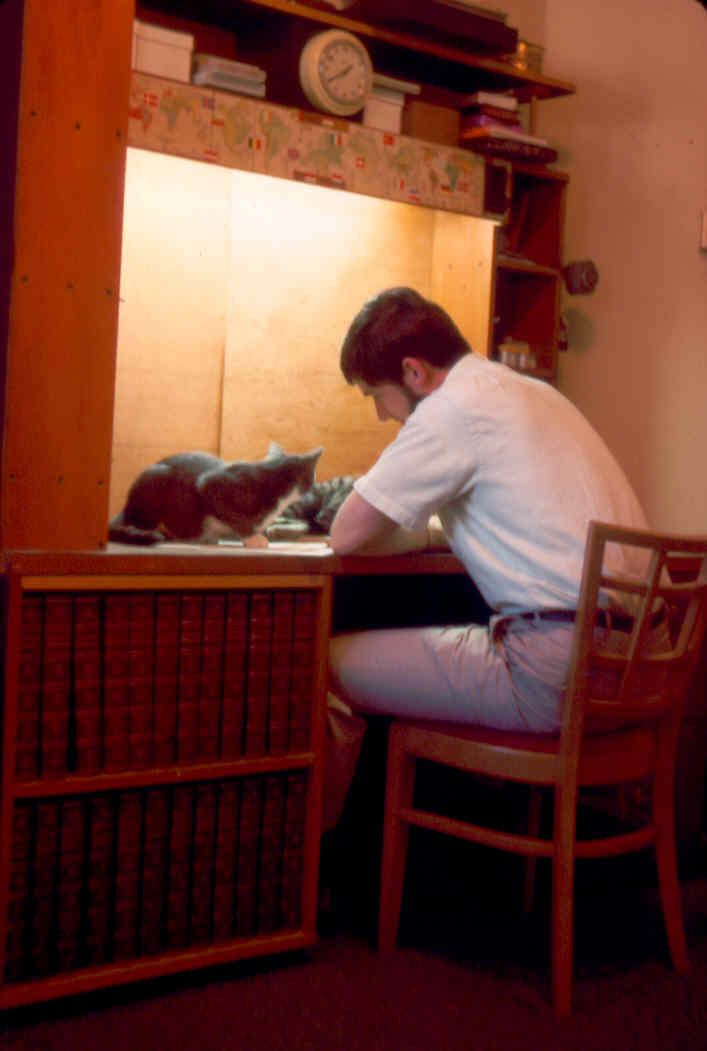

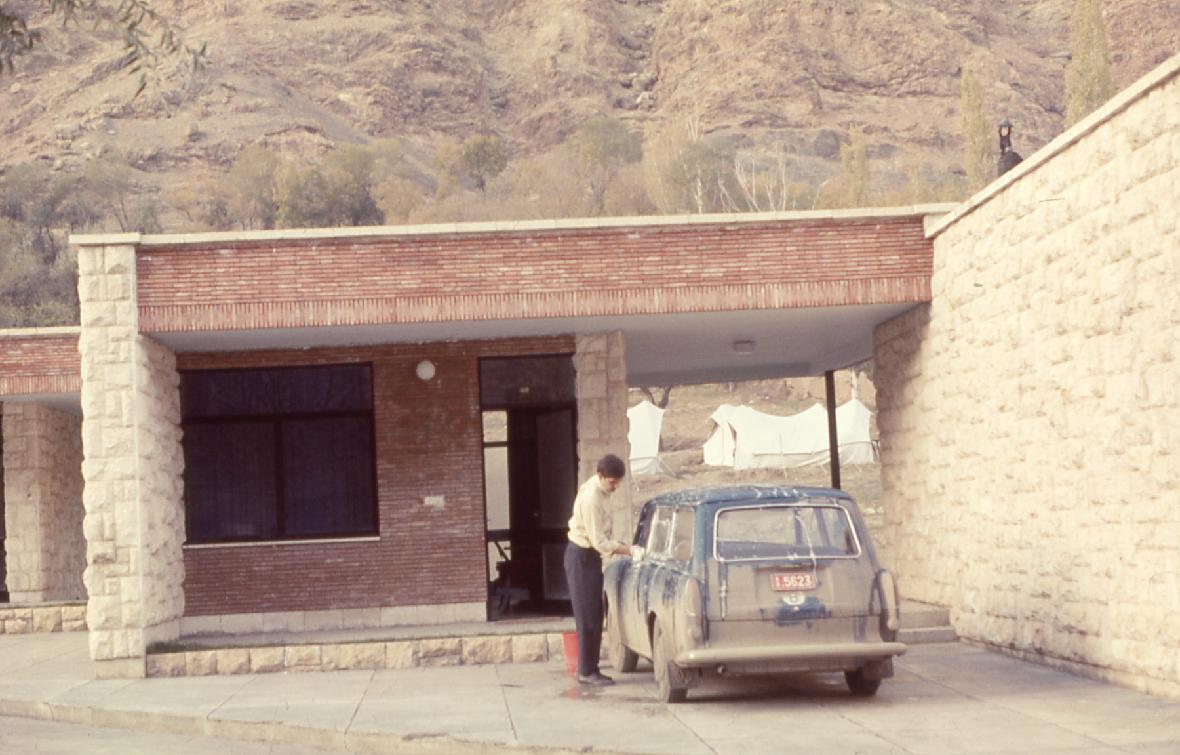

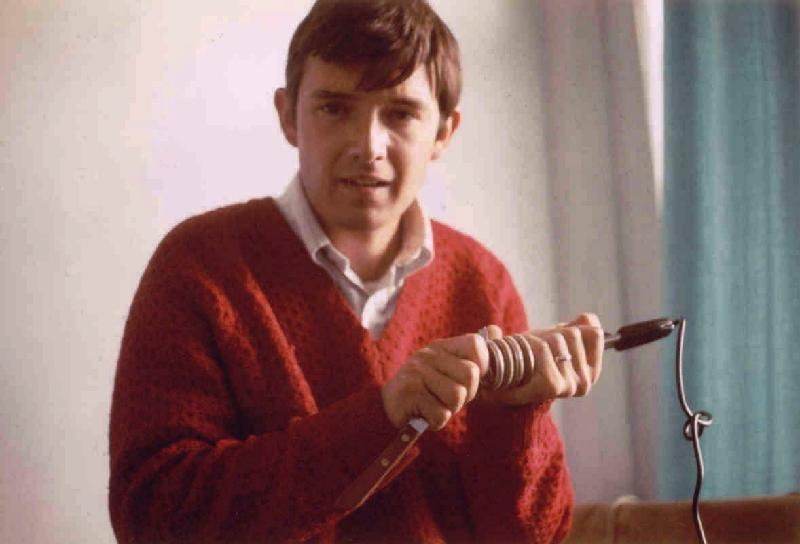

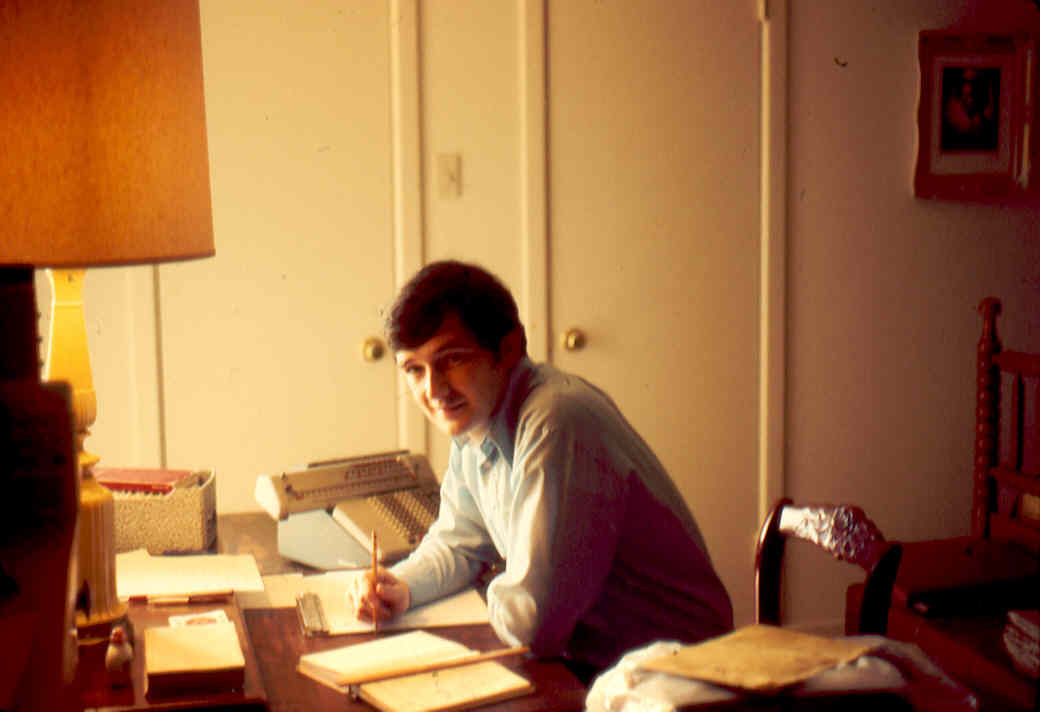

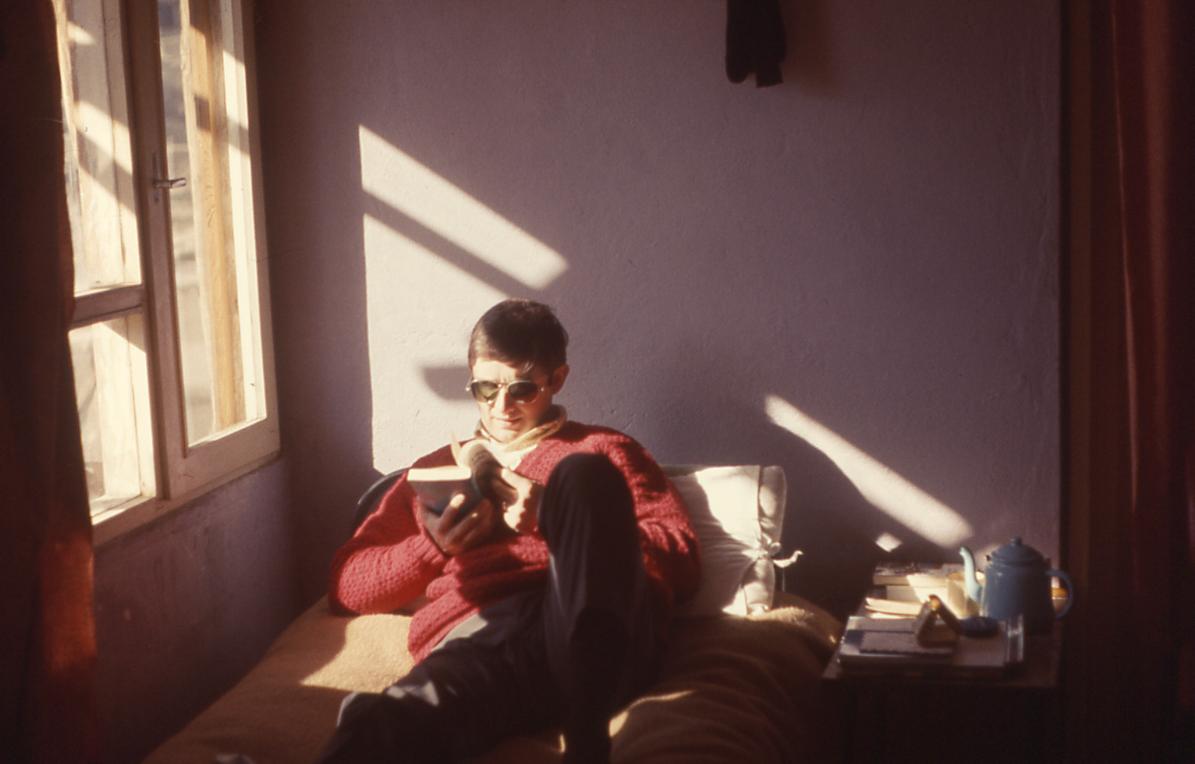

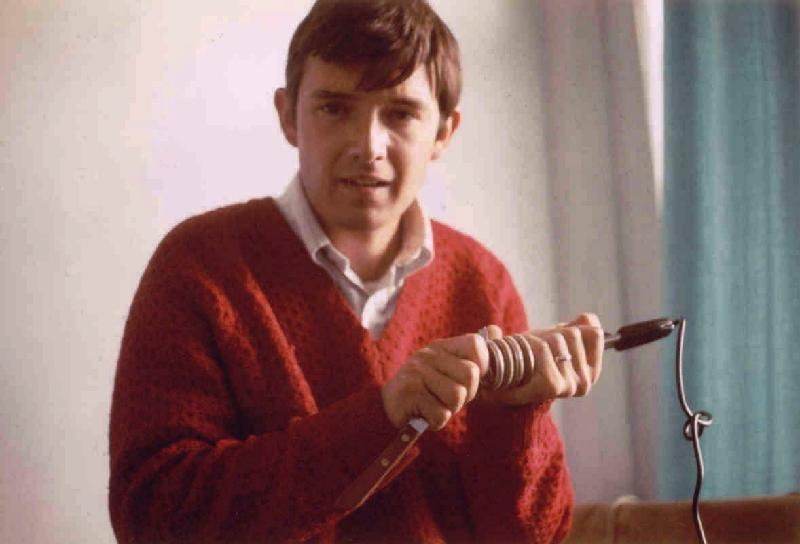

Here I am relaxing in our hotel

room in

Kabul. As we drove toward the Khyber Pass, we found ourselves in major

Pashtun territory ... a rather violent land where people lived behind high walls and men

ventured forth only if well-armed.

|

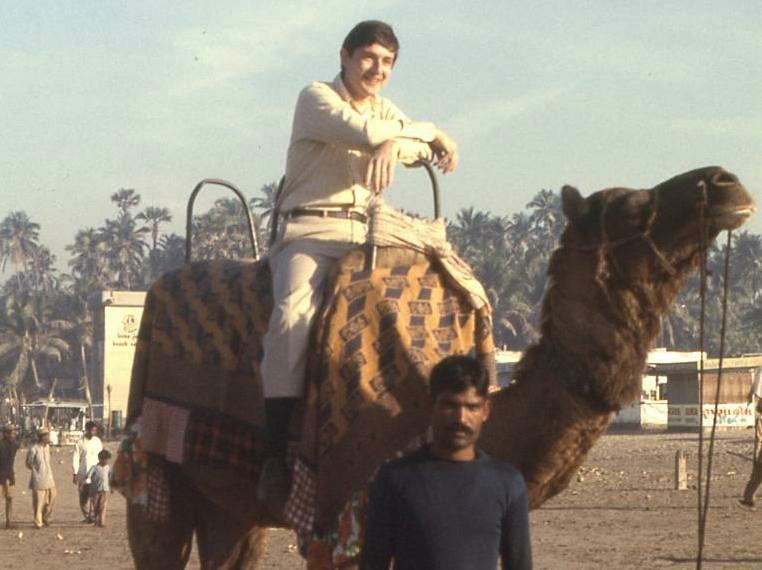

Pakistan and India

Finally we headed south through the famous Khyber Pass and descended

down into Pakistan, a land full of people and animals crowded into the

country's living spaces. The situation was so tight, the roads so

crowded that they were almost impassable, that finally we left our car

in Pakistan and headed on into India by train, making the mistake of

buying cheap 3rd-class tickets for an overnight journey. We could

barely breathe, the train was so crammed with people. The next morning

we switched to the 2nd-class, but soon discovered that Indians had the

habit of invading the 2nd-class cars when the 3rd-class car could take

on not another individual. We finally decided to go 1st-class, which

turned out to be not very expensive, and an excellent way to meet very

interesting individuals.

We finally arrived in New Delhi, and settled in there for over a week,

right off of the very Victorian Connaught Circus. There was so much to

see and do there. At first we loved the food dearly, until we finally

tired of one curried meal after another (even a fruit dish was

curried), and found that the American Embassy opened its restaurant on

Friday noons for Westerners (not many actually) to come there to buy

hamburgers and shakes! Otherwise we had something of a wonderful love

affair with India.

India was such a contrast, of elegance in its historical sites and

poverty in the streets. And India, like Pakistan, was a very crowded

country. I had no idea of how India could possibly continue to expand

its population (actually at the time, it had only half the population

that it does today!)

But I admired the way the Indians went at life. Poverty did not mean

misery. It only meant going at life in a simpler way. I remember

sitting at a window at a railroad station's restaurant gazing out at

the yard below me, where a woman was seated on the ground, assembling a

small fire of cow "chips" to prepare a meal for her small children

frolicking around the yard. There was an amazing "completeness" about

the scene. She was doing what she knew to do to push on in life, and

the kids seemed perfectly happy with the life they were delivered.

It was at that point that it dawned on me that life simply calls on us

to find ways to accommodate ourselves to it, as so many of our own

American ancestors had done in the wilds of America. It was not our job

to push life into a well-ordered box, although that seemed to be our

goal in life these days, at least in my well-ordered American world.

And in finding ourselves in such a well-padded box, we seemed to spend

a great deal of time looking over our shoulders at life, afraid of what

might happen to us if we were forced to live outside that box. So we

did everything in our power to make our box even more secure.

Yet, there in India was grand elegance, splendid reminders of that at

Delhi's Red Fort, where the palaces were breath-taking with their

marble work detailed with semi-precious gems and their hand-cut marble

screens.

It led me to inquire more deeply into the story of the Mogul dynasty

that had built this splendid work (including the Taj Mahal which we

would later visit), of the family's rise, its dominance – then its

decay and ultimately its fall.

I would never forget this. It would later become the inspiration for my

"four generations theory" – of the typical rise and fall of most all

societies (at some point in their existence) – eventually presented in

my university course work, and in my recent publications on American

history.

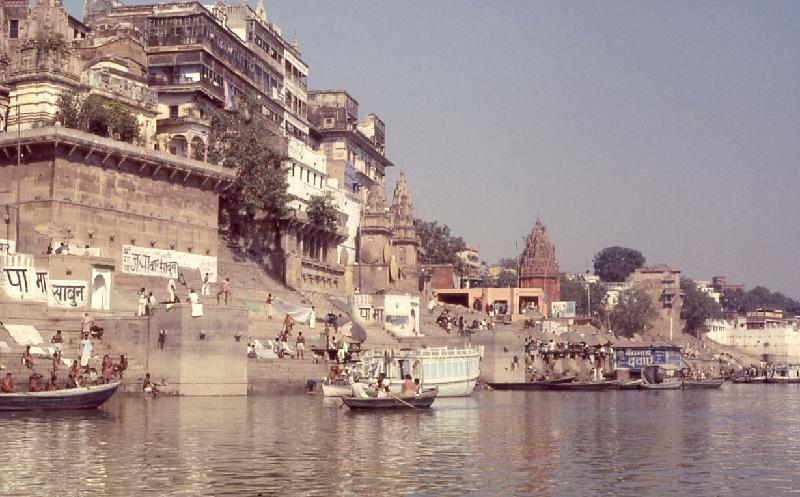

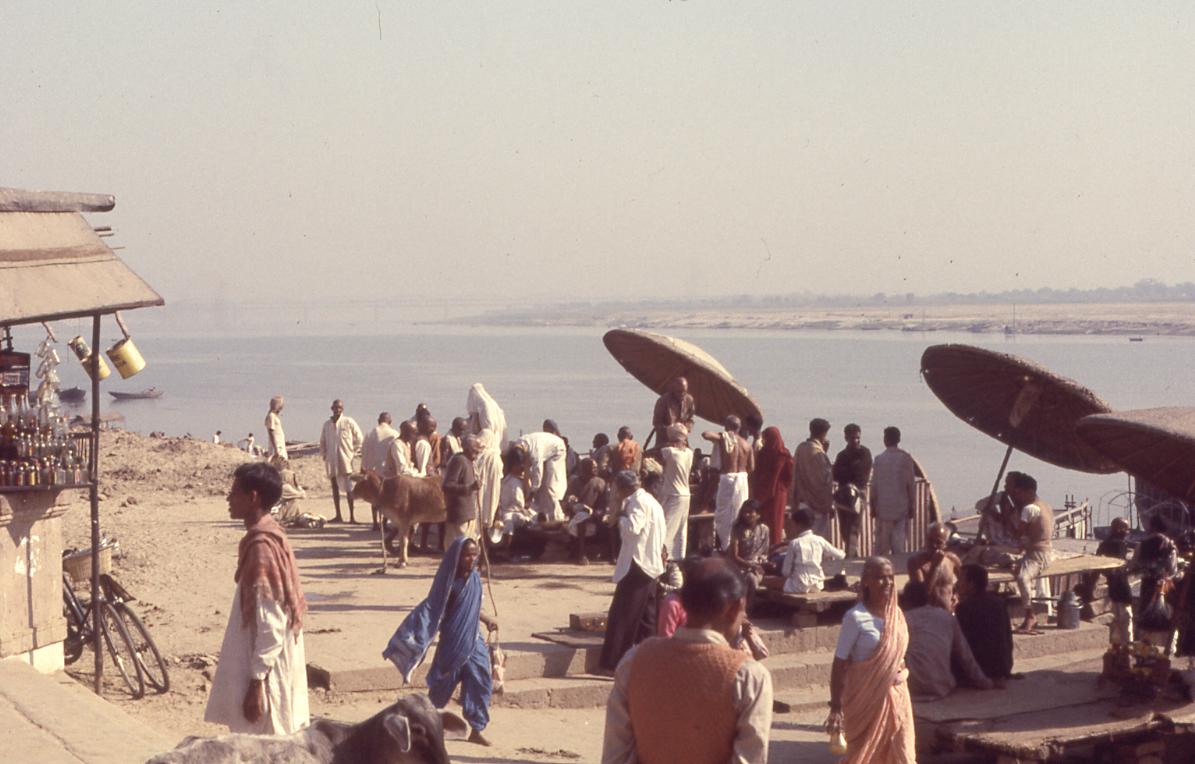

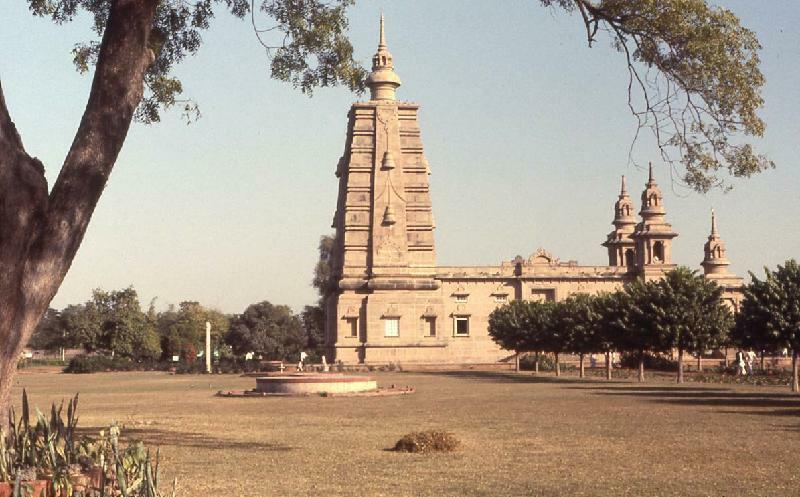

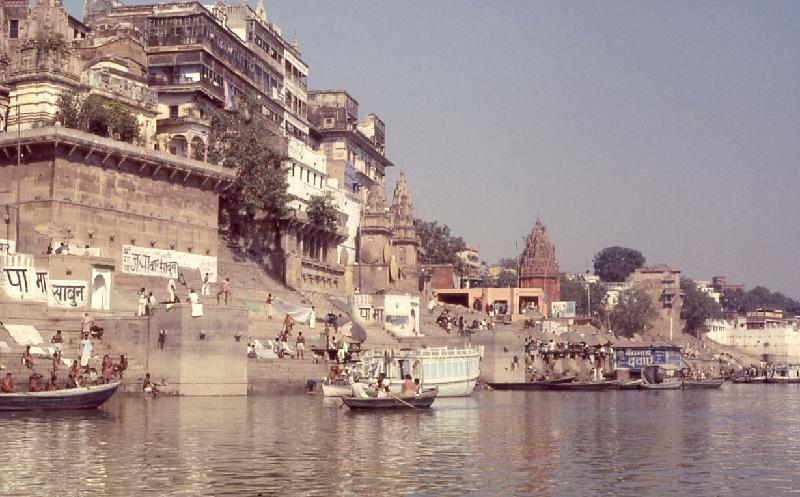

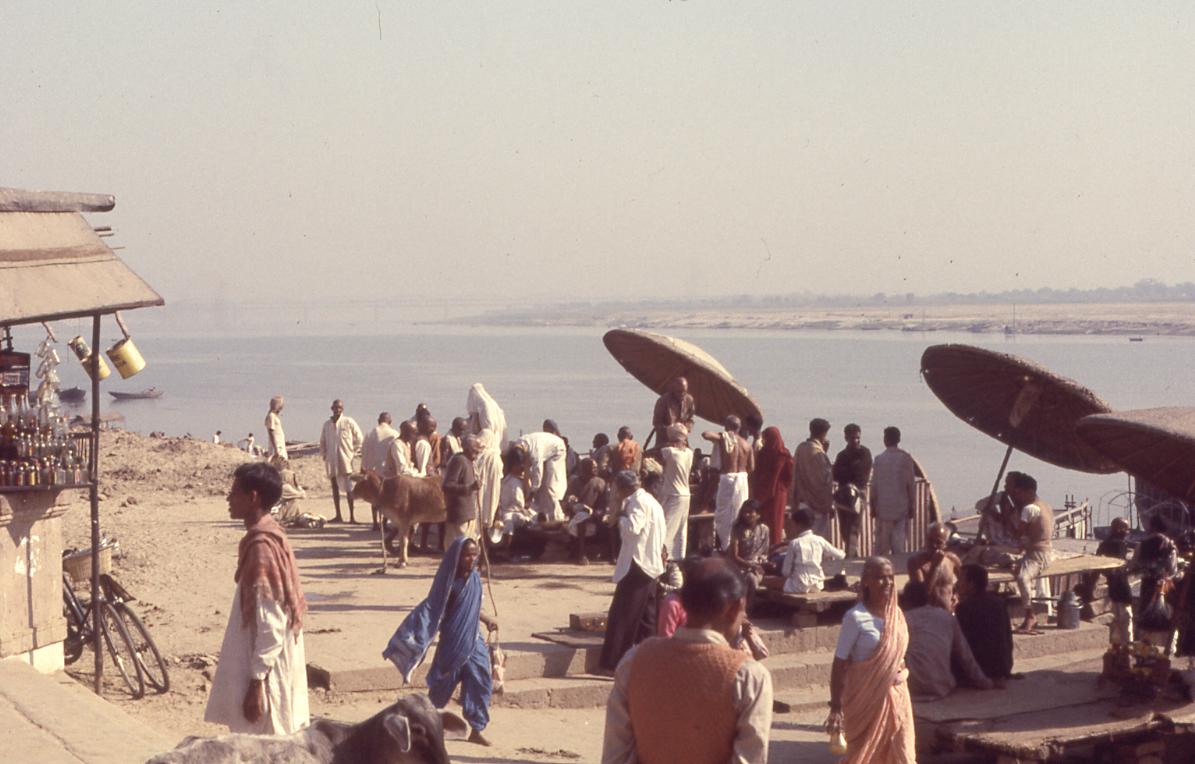

And, of course, we just had to make our way to Varanasi (old Benares),

a "holy city" (both Hindu and Buddhist) located along the banks of the

great Ganges River. There we found Hindu temples, even Muslim mosques,

and Mogul palaces alongside common homes and shops, as well as the

great Buddhist shrine at nearby Sarnath. We watched Indians coming to

the water to bathe in the holy waters and to offer floral wreaths in

thanksgiving for some event in their lives. We saw Indian dobymen

washing the people's clothing, just upstream from where the dead were

being burned at the river's edge and their ashes scattered into the

holy waters of the Ganges. We saw semi-naked holy men at prayer. We saw

sacred cows wandering the streets, not to be touched, even to be pushed

away from food stands where they munched away on the produce offered

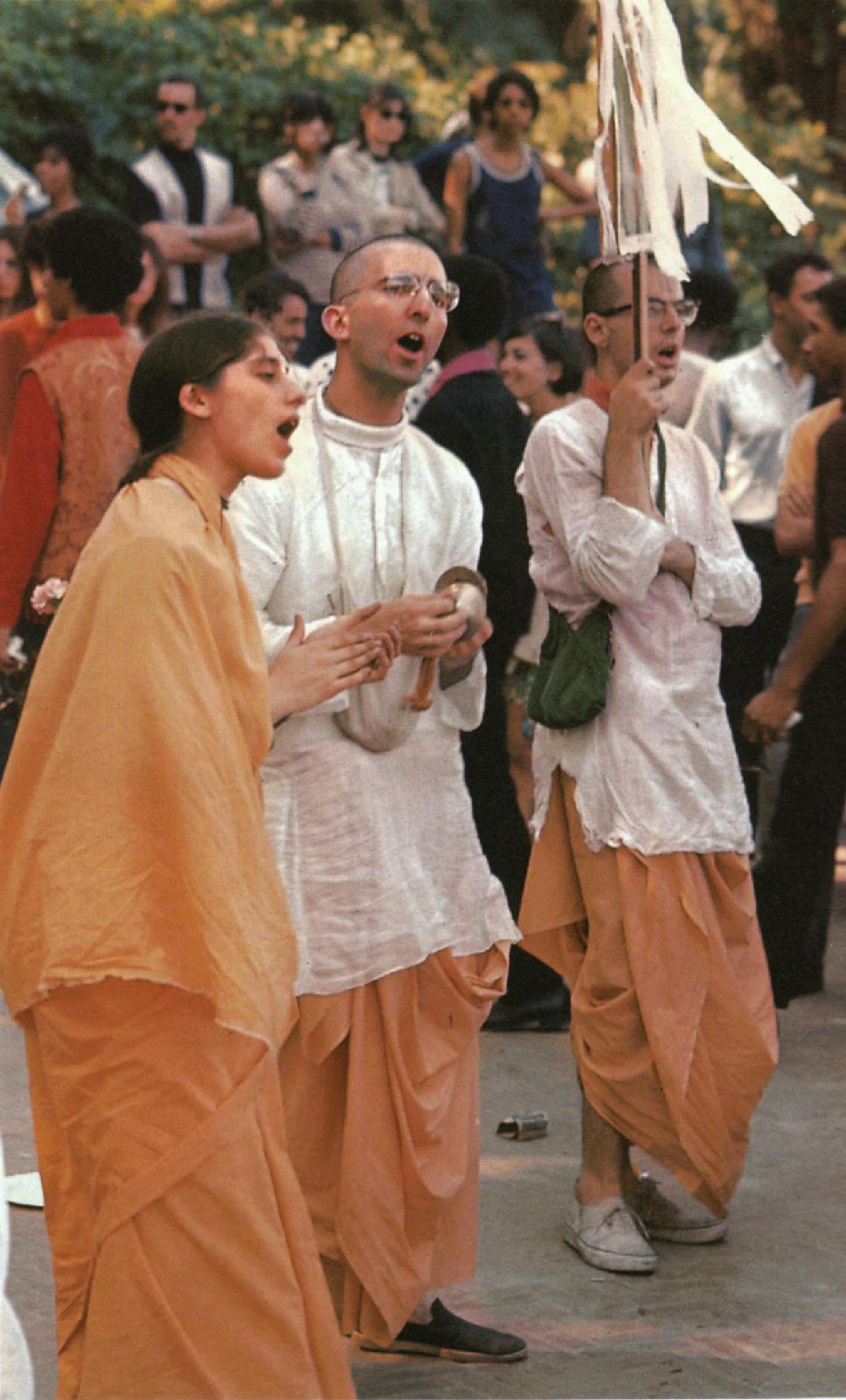

there. We passed religious processions in the streets, etc., etc., etc.

It was so unlike anything you were likely to run into in America (even

a monkey visiting us through an open window as we took breakfast at our

hotel!)

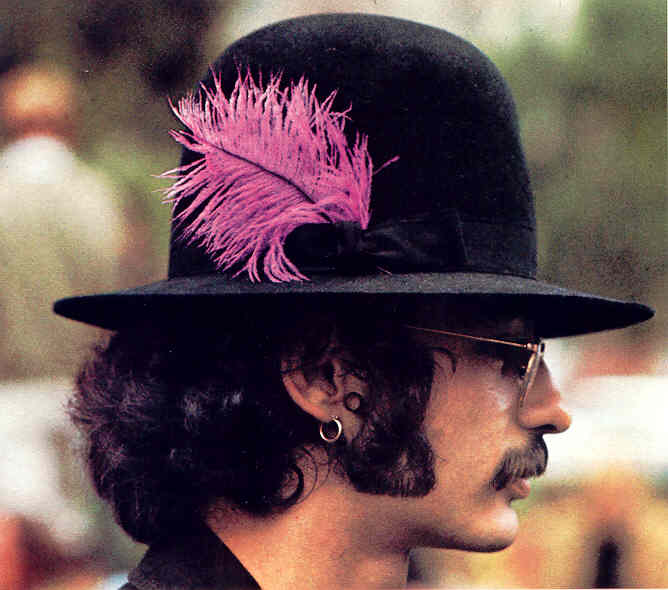

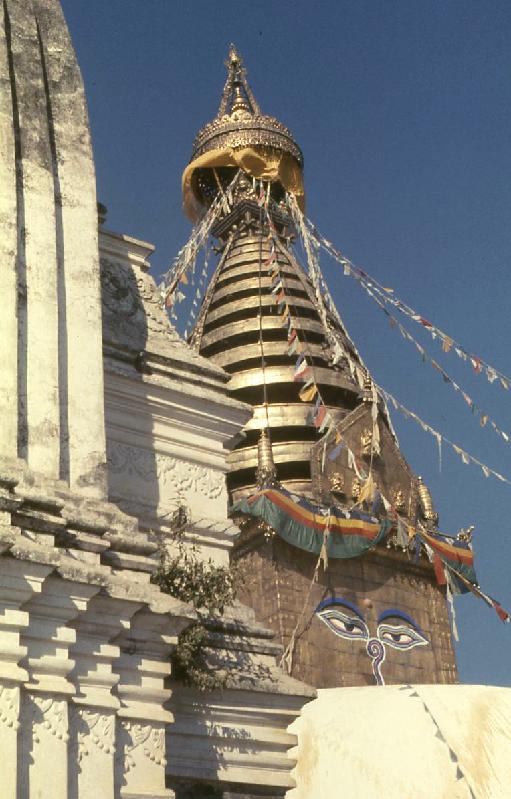

On to Nepal

There was no practical way to get to Kathmandu, Nepal's capital, except

by flight. So we had the privilege – and the glory – of flying over the

foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. And we arrived in a world that

still belonged to an age several centuries ago. It was primitive in a

medieval sort of way, and also glorious in that primitiveness.

However, It was not until we got to Nepal that we also encountered the

craziness that we had left behind in America. In Kathmandu you would

periodically run into some sunken-eyed Westerner who would finally

remember that his or her body needed something besides the inexpensive

and readily available opium to sustain it. They would occasionally drag

themselves to the local Chinese restaurant to get some cheap food

before disappearing again into some hellhole to continue their drugged

existences. Periodically they would be flown out of Nepal in body bags.

Such a dismal end for people who had come so far to "find themselves."

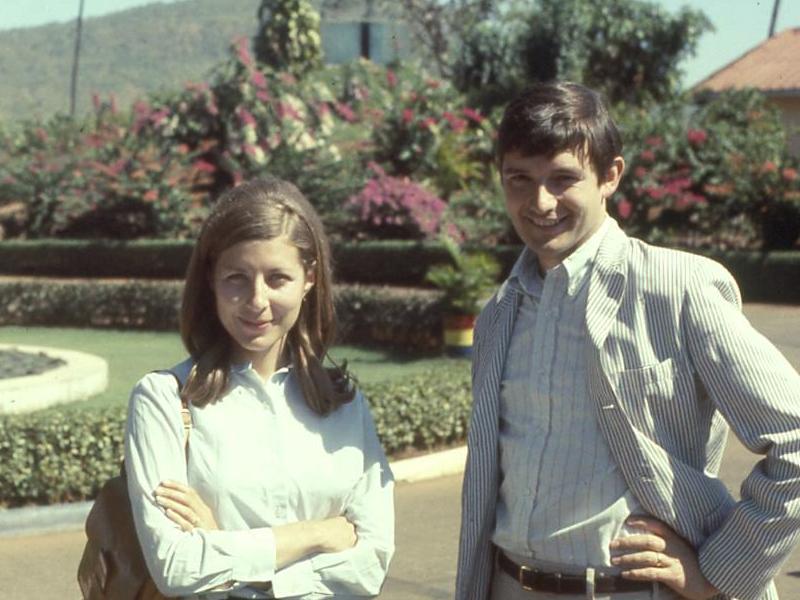

Back to India

We flew back to India and arrived at a still-quite-Victorian Bombay

(the future "Mumbai") just in time for Christmas. It was strange to

note that Hindus found ample reason to celebrate Christmas, in a very

typical Indian way – with bright colors everywhere, music blaring out

onto the streets, and the people parading everywhere, happy to be

caught up in the event.

All of this obviously had no connection whatsoever with the Christmas I

was familiar with. But for me at the time, Christmas anyway was just a

beautiful family holiday on the calendar, to be celebrated for whatever

purpose and by whatever manner you chose to do so. Beyond that it had

no particular meaning. (I was not anti-Christian at the time. Just not

part of that religious world).

|

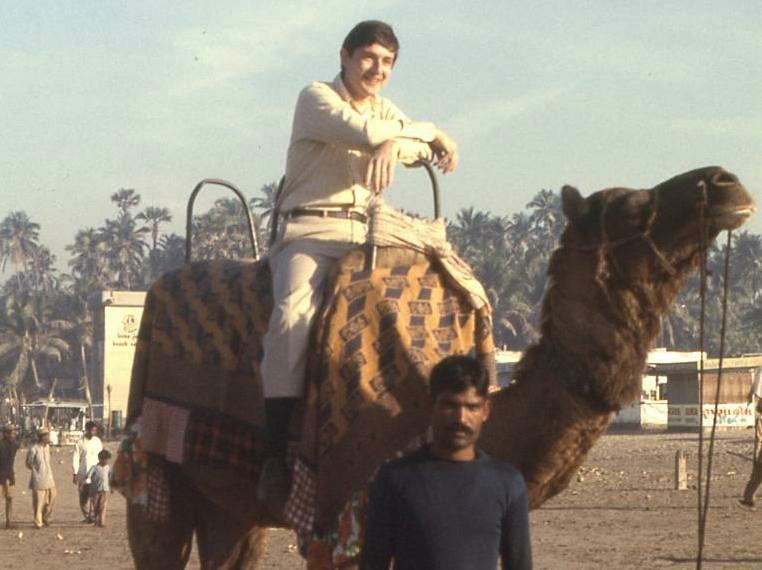

Pakistan, India and Nepal

Then we went

through the Khyber Pass (major Taliban territory

today) … down into the crowded streets of Pakistan … where we left the

car and continued on into India by train!

Then we spent

the next month in

India …

seeing the ancient and the modern (mostly the ancient!) side by

side

Delhi's Temple

dedicated to the goddess Lakshmi

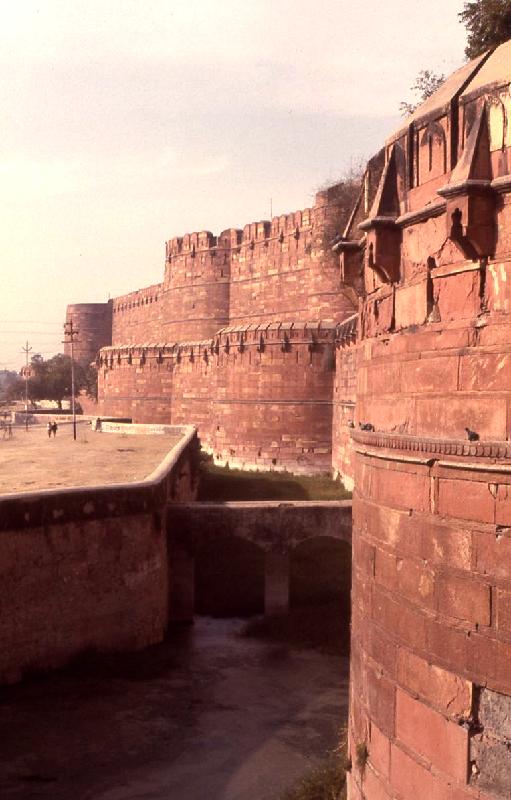

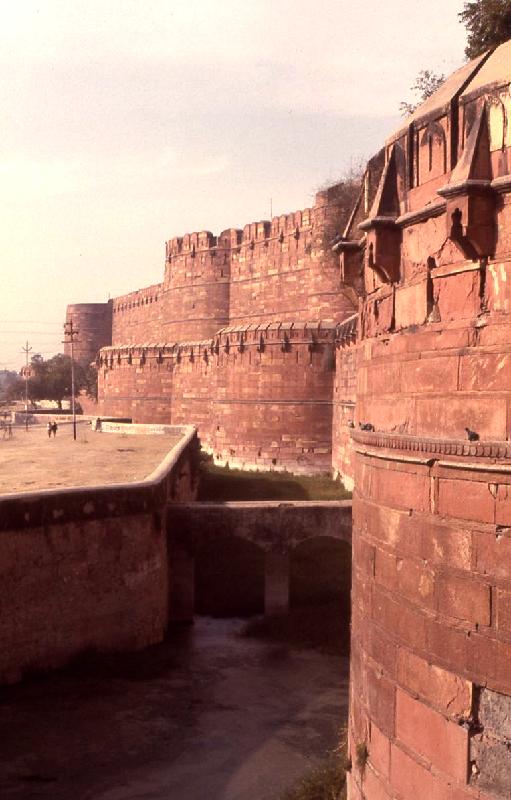

The Red Fort at

Delhi

Along the Ganges River at Benares

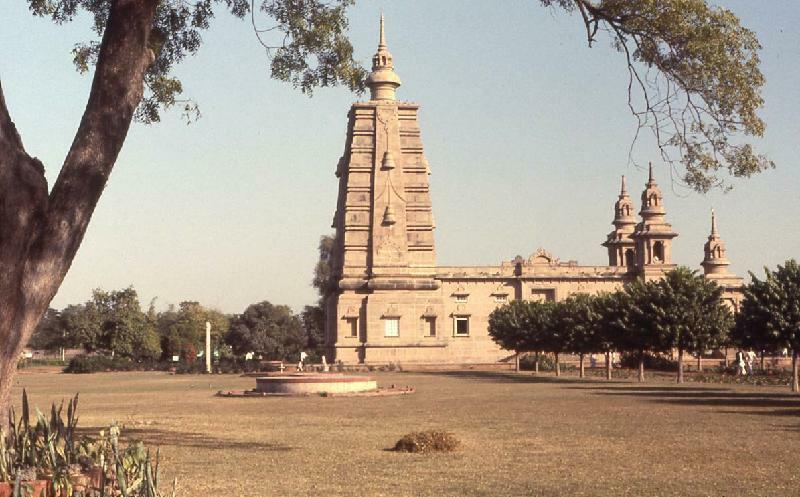

The crowded streets of Benares / the Buddhist holy site at Sarnath

(nearby)

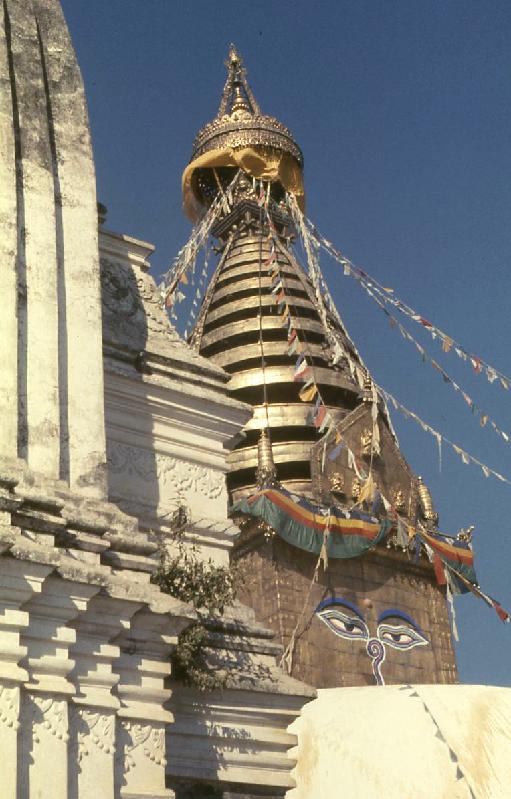

We

then flew across the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains to

Nepal’s capital, Katmandu, and nearby religious center of Patan … where

we felt as if we had stepped back several

centuries in time.

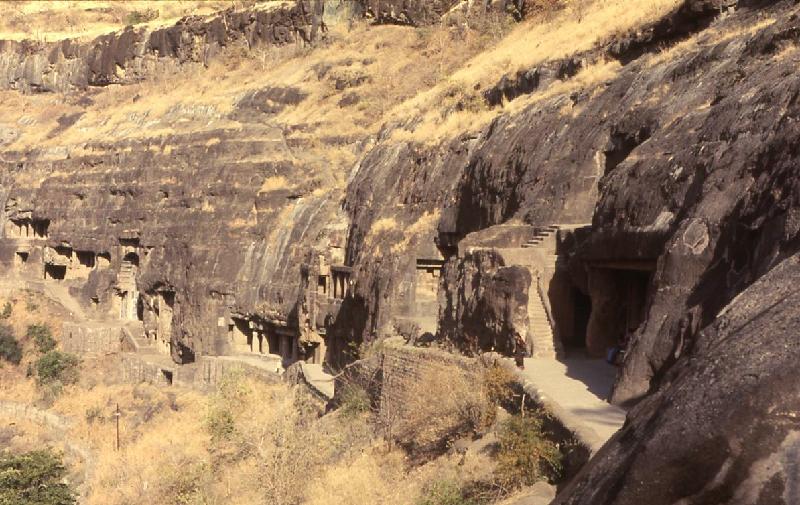

We then returned to India for

another month of travel.

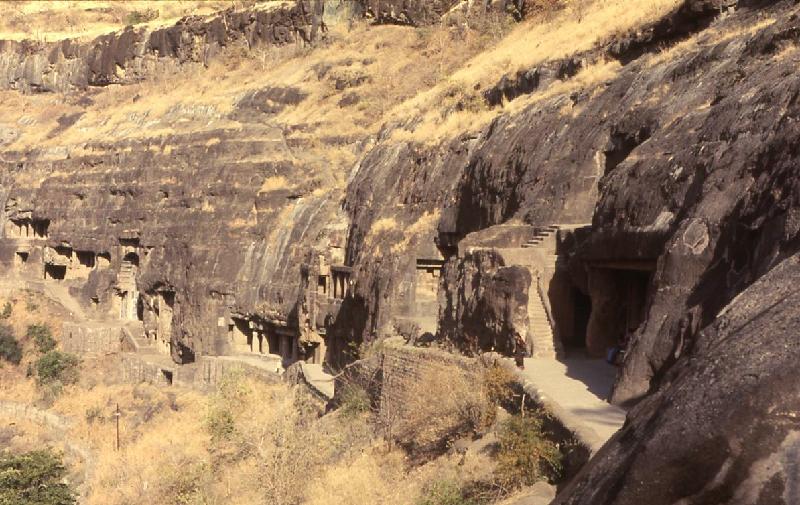

The Buddhist Ajunta caves In Bombay (today’s

Mumbai) we encountered not only remaining

elements of Victorian or British India … but an old friend Deepak (at this

point a professor at the University of Poona) … who also introduced us to

India’s famous movie industry.

A still quite Victorian Bombay (at that time)

We spent a good deal of time with an old friend, Deepak, who was at

that point a professor at the University of Poona. He was now happily married, with children. We spent time

together just relaxing, taking meals along the Indian Ocean, visiting

the ancient Buddhist Elephanta Caves, and visiting a Bombay movie set

where they were filming one of India's many productions.

Deepak was the picture of happiness, especially in his marriage with

Purnima, a marriage arranged by his family of course. I remember when

he got "the letter" commanding him to return from St. Louis (he was

attending Washington University the same time as my father) to Bombay.

As a majorly free spirit at the time, he knew exactly what his father's

intentions were, to end that freedom with a proper marriage.

He explained to me that his father at least had offered him not one but

three candidates. He looked over their resumés (!) and announced that

he would start with Purnima. And after a single date with her, he told

his father that he would not need to check out the other two

candidates. Purnima was an excellent choice – beautiful, well-educated,

a skilled dancing teacher, and of very good family. Indeed, Deepak

could not say enough positive things about the wisdom of the way

marriages were "arranged" in India. I suppose he had a point!

|

Fun with my old friend Deepak

We visited a place where they were filming an Indian movie ...

and of course

we visited more of the requisite historical sites (there being many in India!)

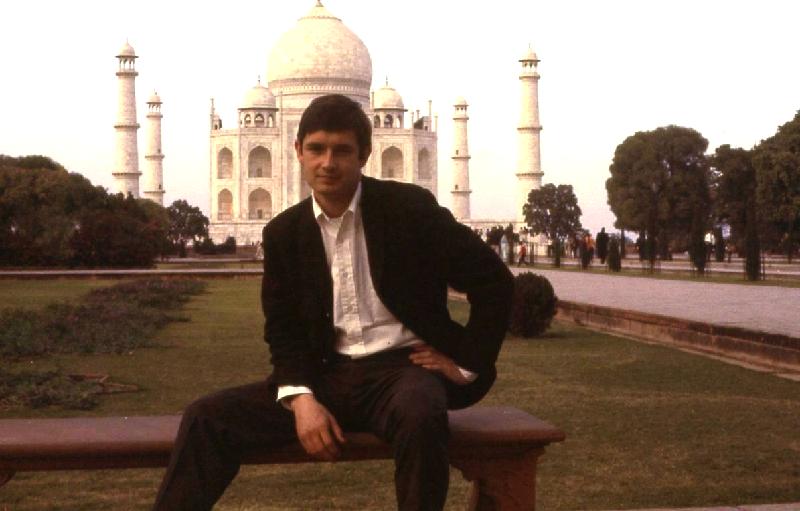

The

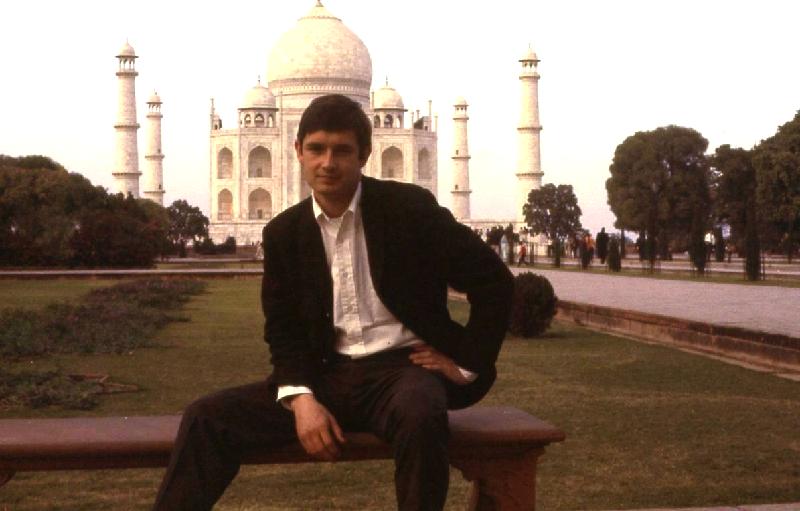

famous Taj Mahal at Agra ... once the center of Mughal imperial power

The

luxurious Agra Red Fort and palaces

Finally in late January we began

our trip back to Belgium

|

Time to head back West

I think that part of the reason for both my expatriate existence – and

my decision to include Asia as part of that experience was a sense that

I would find some of that "transcendence" that my soul craved so much:

a sense of sharing in some of the "wisdom" of countless generations

that went before us. I wanted to plant my personal soul in some of that

antiquity.

But in any case, it was time to get back to "reality." I had a

dissertation to write, and the need to find employment back in Belgium,

where we planned to establish ourselves for the immediate future.

The hand of Fortuna

In the course of the trip I began slowly to develop that rising sense

of some unseen hand surrounding and protecting Martha and me during all

this venture into the unknown. Things that had been happening along the

way seemed to me to be much more than mere coincidence. And it

certainly was more – much more – than just good luck. This "hand" not

only had an invaluable presence, it seemed to have some larger purpose

behind that presence. Slowly this "hand" began to take for me identity

simply as Fortuna.

I certainly would never have called this Fortuna "God," for this in no

way conformed to my Sunday School teaching about the nature of God. But

nonetheless, I did have a keen sense of the outside support of some

kind of mysterious force. The very decision to head East across Asia

with only the crudest of maps available to guide me and no sense of

what I would do if breakdowns or banditry or sickness or something

should afflict me – this was possible for me only because I had this

strong sense of Fortuna.

Most importantly, in very life-and-death moments, this hand of Fortuna

came through for us, when we were in desperate need of assistance. A

couple of the most dramatic instances occurred on the trip back from

India to Europe.

The Baluchi Desert

One such instance occurred when I lost my way from the road (path)

through the Baluchi Desert, for the road was drifted over constantly by

shifting sand. At one point, I found myself hopelessly mired down in

sand in the middle of the Baluchi Desert. I could not dig myself out.

I feared being stranded out there, for in such a defenseless plight

Martha and I were perfect targets for murderous thieves. But as I got

out of the car to consider my situation, I looked up, and – wonder of

wonders – saw two men working off in the distance. They saw our plight,

and came up to help us get ourselves dug out and redirected back on the

road (which they had been working on).

How odd it all was, since they had been the only people I had seen all

morning along the road (it was just desert after all!). And I had

passed very few cars or trucks since heading out that morning. Yet

there they were a few hundred yards off to help us! (angels in

disguise?)

|

This was a very

grueling trip because we had to cross the Baluchi Desert (where

Alexander lost much of

his army on his return West from India). We get bogged down in a

sand drift ... only to find two road workers a hundred yards off, able

to get us back on the "road." Interesting, because these were

about the only people we saw that day. Angels?   We

get a short break from the bad roads and snow when we come to Isfahan

(Iran), the old Persian royal capital ... with the Ali Qapu Palace and Bazaar.

The Iranian-Turkish border

town / The road as we start out

|

The wintry heights of Turkish Armenia

Another such instance occurred a short time later as the car climbed

the snow-covered road to the top of Turkey's Armenian Mountains.

Constant snow storms had killed 14 people in those mountains the

previous week. And arriving at the Iran-Turkey border, we learned that

the border authorities were about to close the main road across those

mountains, the road that would bring us to Erzurum in Turkey on the

other side of the mountain chain. The next morning, I pleaded with the

authorities to let us pass on ahead, as we were running out of money.

And everyone was aware that once closed, the border would not be

reopened for months. They finally relented and let us proceed.

And so there we were, heading up along a heavily snow-covered road with

conditions worsening with each mile. Then it happened: we got

hopelessly stranded in a huge snow drift which effectively blocked the

road ahead, and prevented us from even being able to turn around and

head back to where we had started from. We unloaded everything we were

packing, in order to lighten the car. But it proved to be to no avail.

We were stuck – completely stuck – with snow coming down heavily around

us. And there was no prospect of help, as we had seen no one on the

road since we left the border. At that point we realized that we were

thus destined to become statistics added to the number who had died

from this horrible snow storm.

Then miraculously a truck full of Turks appeared out of the snowy haze.

Thankfully they were determined to help, rather than take advantage of

our hopeless situation. They dug us out of the drift and then swung in

front of us so that the truck blasted its way through the drifts before

us, plowing a path for us through the mountainous heights. And then

when we came down on the other side, to more drivable conditions, they

drove off. (More angels in disguise?)

|

By the time we

reach an equally somber Istanbul, we are completely exhausted.

Finally

in

mid-February we arrived at our European destination … Brussels where I

planned to research and write my doctoral dissertation on Belgian

language issues ... and Belgian political leadership trying to move the

country ahead in the face of those linguistic divisions.

|

Looking for work in Belgium

Upon our return to Brussels in February (now the year 1969), we faced

the immediate problem of finding work – for we had indeed spent all of

our money in those six months of wandering.

I had been warned in Washington by the Belgian consul that getting a

job in Belgium would be an impossibility, as work visas were virtually

unattainable. But I was not one to let such details slow me up. I had

received considerable training in Washington in computer programming,

and once in Brussels I went from American corporation to American

corporation located there in search of employment as a computer

programmer. In the meantime, Martha found a job teaching English at a

language school – paid under the table of course!

But I was turned down in interview after interview – not because they

did not want to hire me, but because they knew there was no way they

were going to be able to get me a work visa. The Belgian government

wanted to place Belgians in this newly opening field of computer

programming. I grew discouraged after about the 10th similar interview

outcome.

Fortuna comes to our aid again, and again!

Being discouraged by this

was something new to me. I would never have thought simply to arrive on

the scene in Belgium to begin looking for a job if I had not had this

sense of this mysterious Fortuna being "with me." But now it seemed to

be failing me.

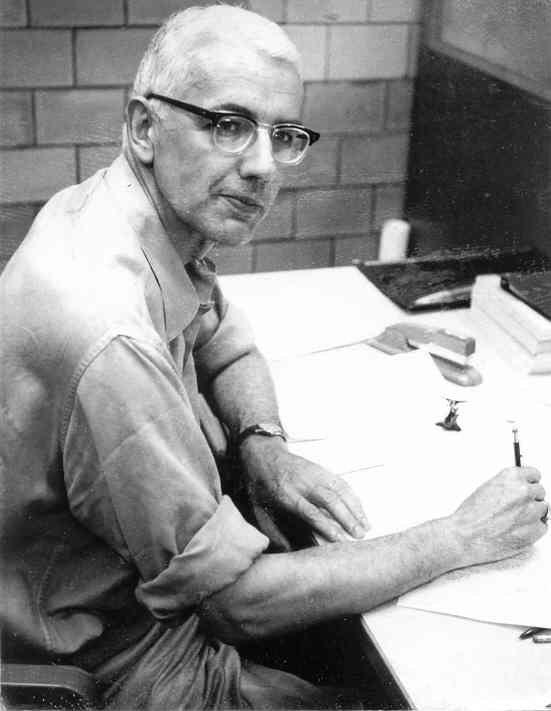

IBM

And then IBM-Belgium contacted me! They had heard I was interviewing,

and wanted to know if I would be willing to be interviewed by them! As

it turned out, they desperately needed a programmer/analyst who could

work directly with their new American customers in Brussels in

developing customized computer operations. Their Belgian staff were

having difficulties with the subtleties of American business language.

They badly needed an American to bridge that gap. Therefore I was

exactly what they needed. And not to worry about the visa. They could

get one granted on the basis that I possessed skills (native

English-speaker) that they could not get from a Belgian national. I was

hired on the spot!

Fortuna had come through for me again!

At about this time Martha was hired by an English-speaking Catholic

school in Brussels – and we were on easy street! Indeed, Fortuna was

busy for us both!

I enjoyed the work immensely. And I had the great satisfaction of being

able to solve some programming problems that had some of the other IBM

technicians stumped. And I was able to work closely with both Toyota

and Ampex offices in Belgium.

But any thought of being able to work for IBM and at the same time

press forward on my doctoral research was soon dispelled. IBM left me

little time and energy for such an enterprise. I simply had nothing

left of me by the evening energy-wise, nothing able to undertake the

rigors of doctoral research.

But by the fall, Fortuna performed yet another miracle for us when

Martha got an even better job teaching at the American military school

in Brussels. We could live easily (even splendidly) on her salary

alone. So I resigned from my job with IBM and turned my attention to my

doctoral work. Life was good. No, it was perfect!

|

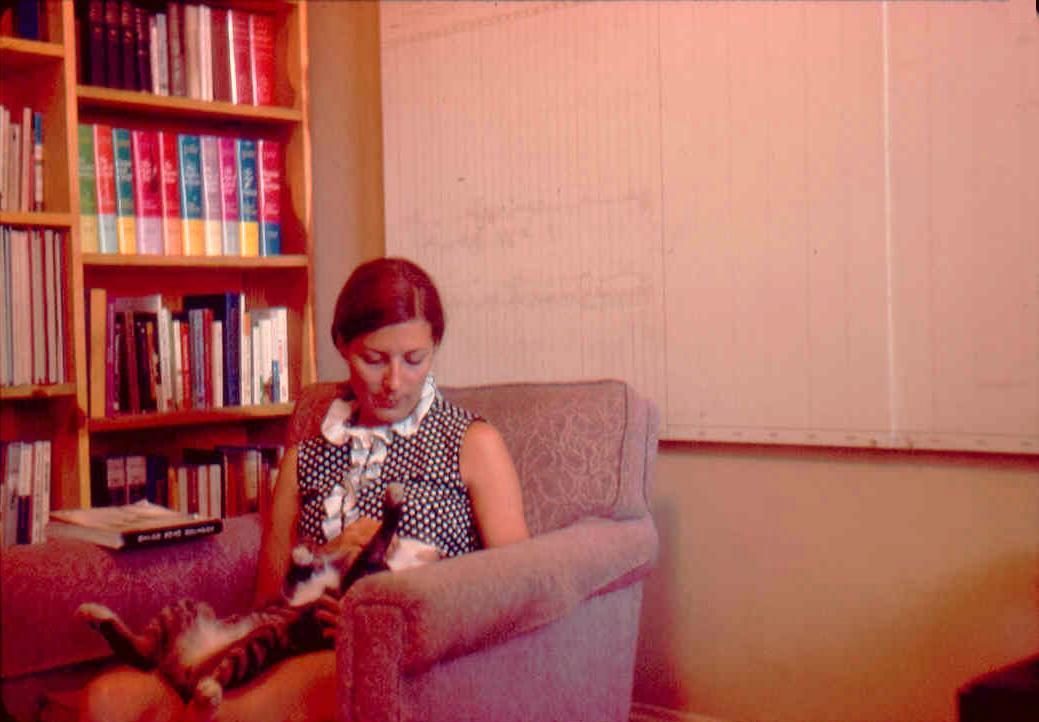

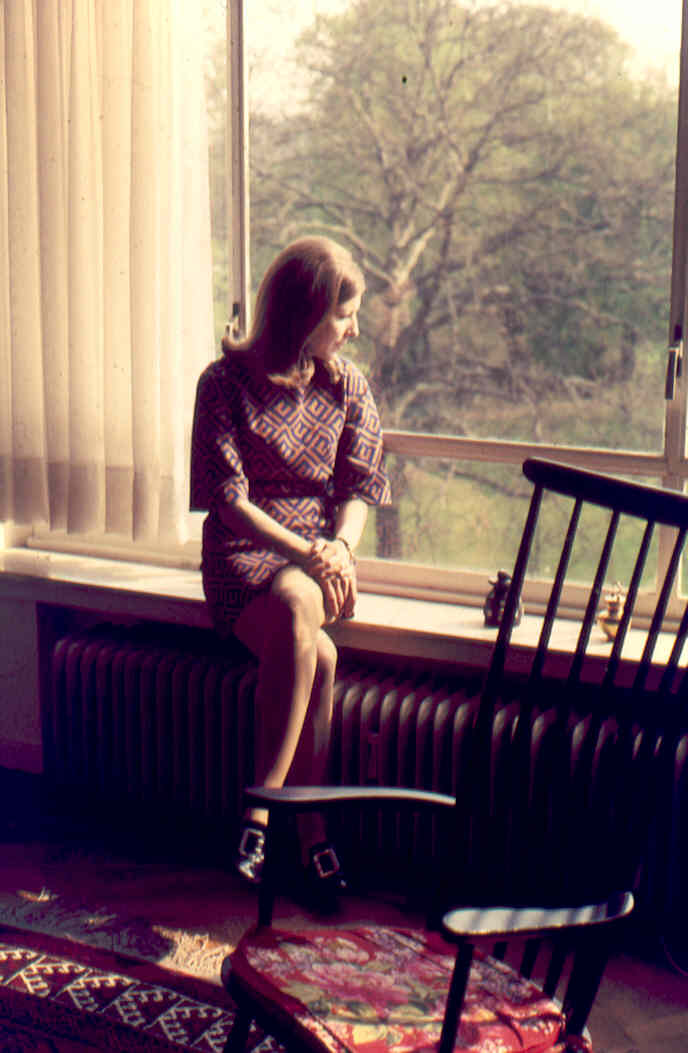

We soon found

an apartment just in time to receive a visit from

Val

– and Courtney’s cousin Jane. At that point, furnishings were

scarce! However, we eventually got settled in quite comfortably!

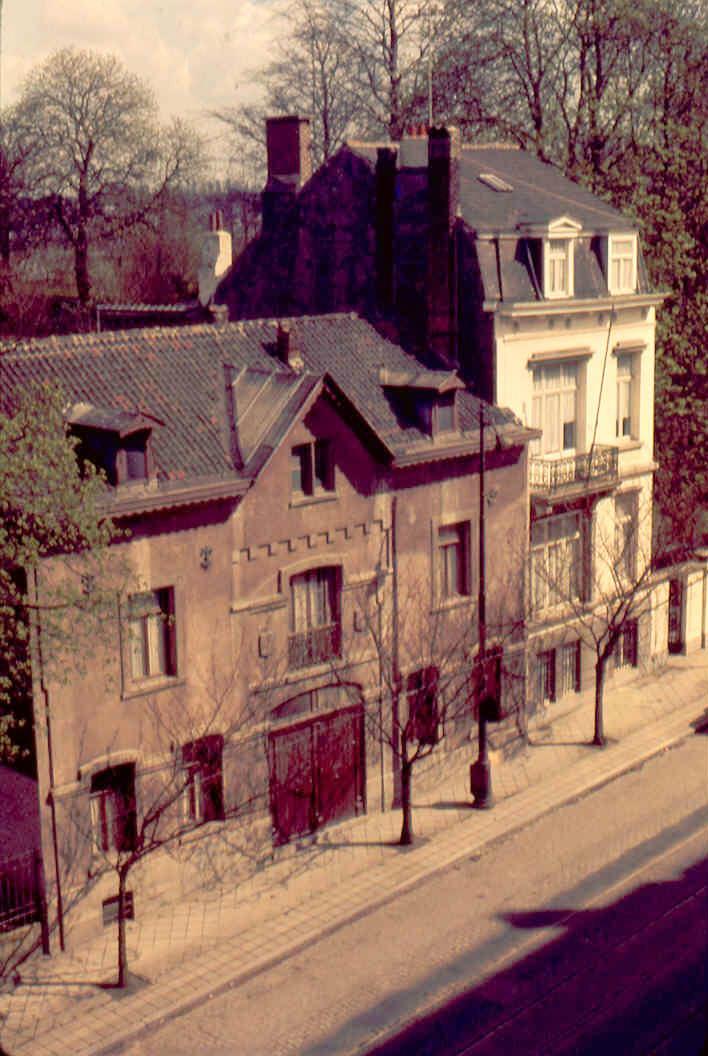

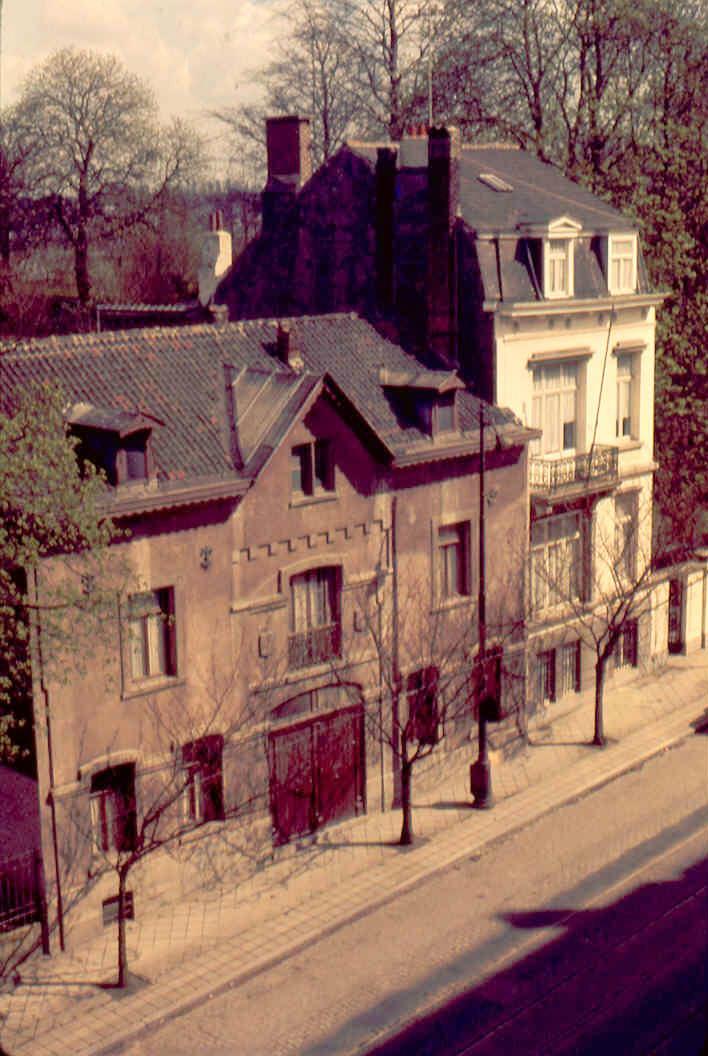

Welcome to our apartment building! We loved to sit on our

balcony ... We loved to sit on our

balcony ...

and look out on our neighborhood (Ixelles or southern Brussels)

Avenue du Derby ... from our balcony

very spectacular when the cherry

blossoms bloomed On this

basis we quickly made ourselves at home in Belgium

|

Friends

It was an active time socially. We received visits frequently from our

families, and both Val and Courtney's cousin (also a former roommate of

Martha's) came to visit.

And of course, I met a number of young Belgian professionals through my

IBM days, and for the year and a half we were Belgian residents, we

remained close to them – especially our Walloon (French-speaking)

friends, Pierre and Anne, and our Flemish (Dutch-speaking) friend,

Victor. Indeed, Victor became like another brother to me.

At Martha's school we became close friends of a number of American

teachers, expatriates and adventurers like ourselves and most like my

German friends in Geneva – in their tendency to travel forth at every

opportunity. We did a lot of traveling with them.

And I met two Americans (from Tulane University in New Orleans) who

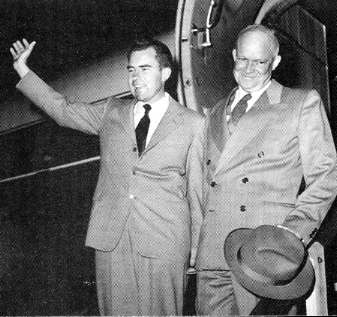

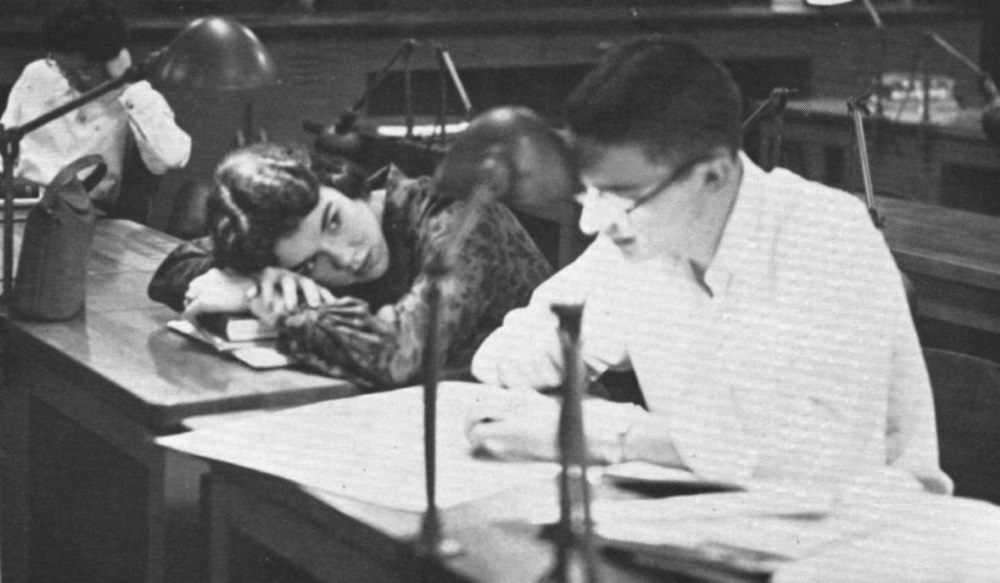

were, like me, researching their doctoral dissertations at the Royal

Library in Brussels: Bob and Newt. We established the almost daily

habit of having three-hour lunches over beers at a nearby cafe,

designing solutions to the problems of America, and the world!4

All in all, Martha and I found that our Belgian life was every bit as stimulating as the life I once knew in Geneva.

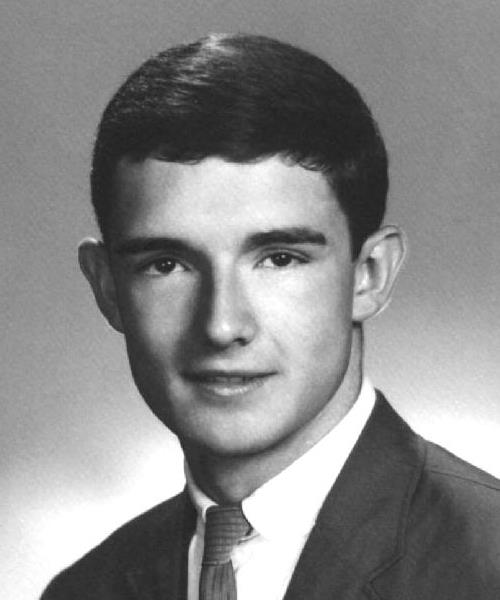

4Newt

would have the opportunity to put those thoughts to action. After

teaching college in Georgia, he ran for the U.S. House of

Representatives, was elected, and quickly rose in the ranks of the

Republican Party, eventually becoming House Speaker, and the force

behind the "Republican Party Revolution" of 1994!

|

In Liège with Pierre and Anne and family Being invited into the homes of our

Belgian friends ... was like being accepted into family ... a great

honor! On a canoe trip

in the Ardennes Forest with

Belgian friends

But IBM drained all my energy daily … and I was making no progress on my

dissertation. Then finally with Martha’s job at the American

military school, we could then easily live off her salary alone.

I quit IBM (to

their great surprise) after 9 months and headed off to the Brussels library to begin my

research … and that first day met two grad students from Tulane

University (New Orleans) also doing doctoral research: Bob Sanders and Newt

Gingrich. We would become close friends … taking long lunches together

… and discussing the problems of the world … but especially those going

on back in America.

Bob

Sanders

and his Danish wife Ann

Newt Gingrich

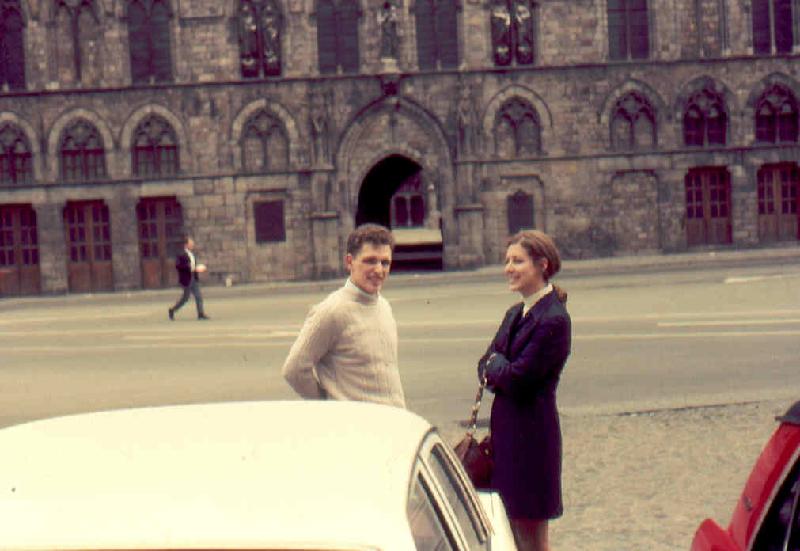

Belgium

itself was beautiful ... and we did a lot of touring the area. We

spent a lot of time in London as well ... and traveled to Paris a

couple of times.

Here we are in Bruges / Brugge (depending on French or Flemish

pronunciation!)

|

Researching "identity politics"

Multiculturalism had become for me a matter of supreme interest. Of

course that summer of 1960 traveling through Europe and discovering the

wonder of many different cultures – and the discovery, by way of

contrast, of how very American I was – constituted the huge startup of

this interest. And my 1961-1962 school year in Geneva had only taken

that interest deeper. And my research on multicultural South Africa

(1964-1965) had pushed me to ask questions now of what politically this

could mean to a society. And my trip across Asia had stretched my

familiarity with multiculturalism beyond even the realm of Western

culture itself.

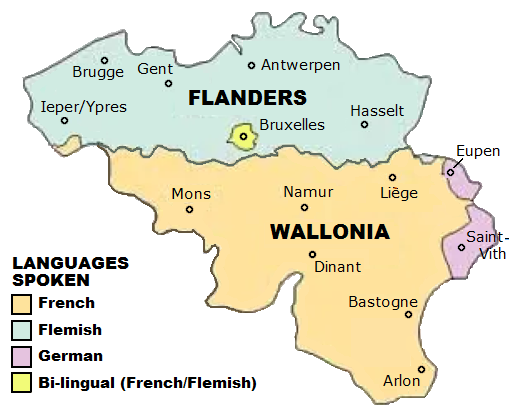

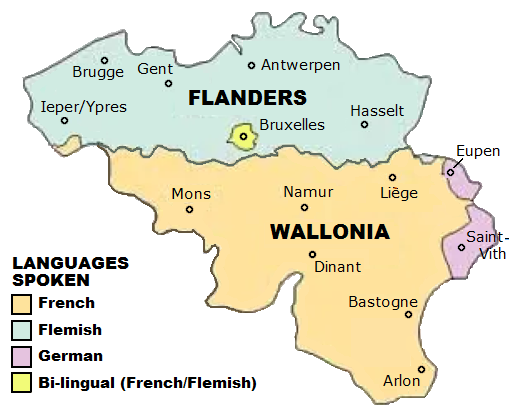

And so now I was in Brussels, Belgium, taking up the matter as serious

doctoral research, trying to understand the political-social

implications of Belgium being a society separated deeply by the

language line of Dutch-speaking Flemish in the north and

French-speaking Walloons in the south.

At one time (the 1800s, when the country was formed) Belgium had been

more or less unified by the fact that the country's political elite,

even in the Flemish North, were fluent in French, as French was the

language that the upper classes of Europe expected everyone to operate

in.

But the nationalist impulse unleashed by World War One, and the German

occupation of Belgium during that war, had encouraged a reaction by the

Flemish (Dutch is after all merely another German dialect) against the

country's francophones (those who speak French). And World War Two and

another German occupation had not softened Belgium's cultural

animosities either.

The challenges – and dangers – of multiculturalism

In any case, I was

very aware of how much language shaped, defined, and directed culture,

especially in this age of nationalism. Language is the means by which a

society's dreams, its understandings, its plans are conveyed to the

people. It is very, very hard to sign onto a society's cultural doings

if you do not speak the language of that culture.

Yes, I am well aware that Liberals somehow believe that

multiculturalism is a blessing to a society because it promotes

"diversity" and diversity supports "freedom." At least it is supposed

to do so in theory.

Actually I never saw that to be the case out there in the real

world. In all my research into the dynamics of multiculturalism I

came to understand quite clearly that multiculturalism was not a

natural blessing. Instead, it was a very dangerous challenge –

one that had to find some kind of larger solution to it, before it tore

a society to pieces. The American Civil War presented a clear example

of just those dangers. So did the Russian and Chinese Revolutions. So

also did Gandhi's revolution in India, which set Indian Hindus against

Indian Muslims and against Indian Sikhs – even destroying Gandhi in the

process. The world around me gave constant witness to that truth. And

it would continue to do so in the future.

Switzerland

But what about Switzerland? Wasn't it multicultural, with parts of the

country speaking French, parts speaking German, parts speaking Italian,

and other parts speaking variants of an ancient Latin form called

"Romansh"? Wasn't it a multicultural society, seemingly always found in

a constant state of peace?

The answer to that, as I well knew personally, was "yes." But I also

knew why, and it had nothing to do with the Swiss fashioning themselves

into some kind of higher species, able to operate in the upper

atmosphere of Liberal enlightenment.

The Swiss were in fact a very down-to-earth or socially practical

people, who had created a multi-cultural confederation of 26 very

self-sufficient cantons. It was at the local level of the canton where

the real business of government (and everything else) took place.

The point at which Switzerland approached the character of a nation was

almost solely in its own self-understanding as a people united against

the larger world. In fact, it was in the requirement of Swiss military

service that there was a larger or "national" political call placed on

the Swiss. And this was strictly a defensive call, one to protect the

country from the intrigues of the larger powers surrounding their small

but mountainous world. In short, Switzerland was basically a defensive

alliance of 26 rather autonomous cantons.

The language issue was for the Swiss of significance only at the canton

level, where there indeed, one or another of the languages supported

the cultural identity defining that particular canton. True, the Swiss

tended to be multilingual, in their ability to speak across cantonal

lines. But still, they were first and foremost French, German, Italian

or Romansch-speaking Swiss (there is no "Swiss" national language).

And the Swiss had no aggressive foreign policy. Indeed, their policy

was to stay out of everyone else's business, and keep everyone else out

of theirs. Beyond that, they needed no nationalist cause (such as what

drove World Wars One and Two) to define them. In fact, they laid very

low during both wars, using their considerable mountain defenses to

keep the warring parties out of their country.

Indeed, in virtually everything, they have performed as diplomatic

"neutrals," joining none of the European alliances – except for the

multinational organizations, the League of Nations and its successor

the United Nations – whose European regional headquarters in fact have

been located in Swiss Geneva. They have even refused to join the

multinational European Union.

So yes, the Swiss found a very effective answer to the challenge of

multiculturalism. But for the rest of the world to be able, or even be

willing, to go down that same "confederational" rather than national

road was, and still is, most unlikely. The crusading spirit of

linguistic or sectarian nationalism in our world has always been much

stronger than the kind of self-restricted and purely defensive

instincts that have long directed Swiss behavior.

Bi-Cultural Belgium

Yet, something (sort of) along those lines I realized was beginning to

redirect Belgian cultural politics, even as I first took up the subject

in late 1969. And Charles De Gaulle was a big help in this matter!

De Gaulle hated the English-speaking world, and blocked British entry

into the European Common Market. And step by step he also removed

French participation from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO), because it was clearly led by the United States. When he failed

to get other European nations to join him in this NATO boycott, he

kicked not only all American troops out of France, but also NATO

headquarters (which had been placed in France) out of the country as

well.

At this point NATO shifted its operational center north, to Belgium,

where the administrative center of the new European Union (the Common

Market and its evolved successor organizations) was already located. In

doing so this gave Belgium something of a very key international status

as the "center" of the New Europe, politically, economically and now

militarily as well. And American corporations followed that shift in

also moving their European headquarters to Belgium, which I well knew,

having worked (via IBM) in these new offices.

And this shift proved to lift Belgium above the linguistic squabbles

that had previously bedeviled Belgian politics, when political actors

had previously played on cultural sensitivities to advance their

particular careers. Now Belgian politicians had a higher purpose,

competing to be the better party to lead Belgium even further forward

in its new role as administrative center of the New Europe.

Lessons learned

Of course, as I was doing my research (and ultimately

writing) on the subject in the period 1969-1970, this new dynamic was

only in its infant stages. But I saw where things were going to be

taking Belgian society… and how its new higher national purpose would

help it move past its linguistic or cultural quarrels.

And I would never forget what I learned in digging deeply into just

this kind of social dynamic. It would serve me well in later years in

understanding the most likely paths that this or that sectarian social

or political movement was likely to take a society, and where a higher

and more unifying purpose might better take that society.

And I learned especially the key role that leadership played in the

process, for vision and resolve to move toward higher things did not

just come by nature to a people. It had to be designed and presented

before the people by those who could explain, and – most importantly –

give clear personal example to the people of what these higher things

were all about.

A true leader needed only to "inspire" the people. If he had to become

a "dictator" in this matter, it was clear that the groundwork for a

higher social purpose was still lacking. The people were still unable

(most likely because of continuing sectarian or cultural differences)

to let go of their social prejudices, and move with their leader to new

things. Stalin faced that problem, Hitler did not. Gandhi, despite a

willingness of both Muslims and Hindus to work together to get the

British to "quit India," could not find a way to get Muslims and Hindus

to work together after that. Indeed, the two Indian groups became

bitter enemies. Mao never figured out how to get rural and urban China

to work together – and nearly ruined China, twice. And so on.

So yes, I would watch closely how I saw a society's leaders approach

the political-economic-cultural and even spiritual challenges facing a

country. Would they merely advance their political careers by

cultivating support among one social grouping, against another group in

their society (and its leaders)? That was classical political

sleaziness, not uncommon in societies that call themselves

"democracies," where the people are easily mobilized to action because

it is their group duty (quasi-patriotism or just crude sectarianism) to

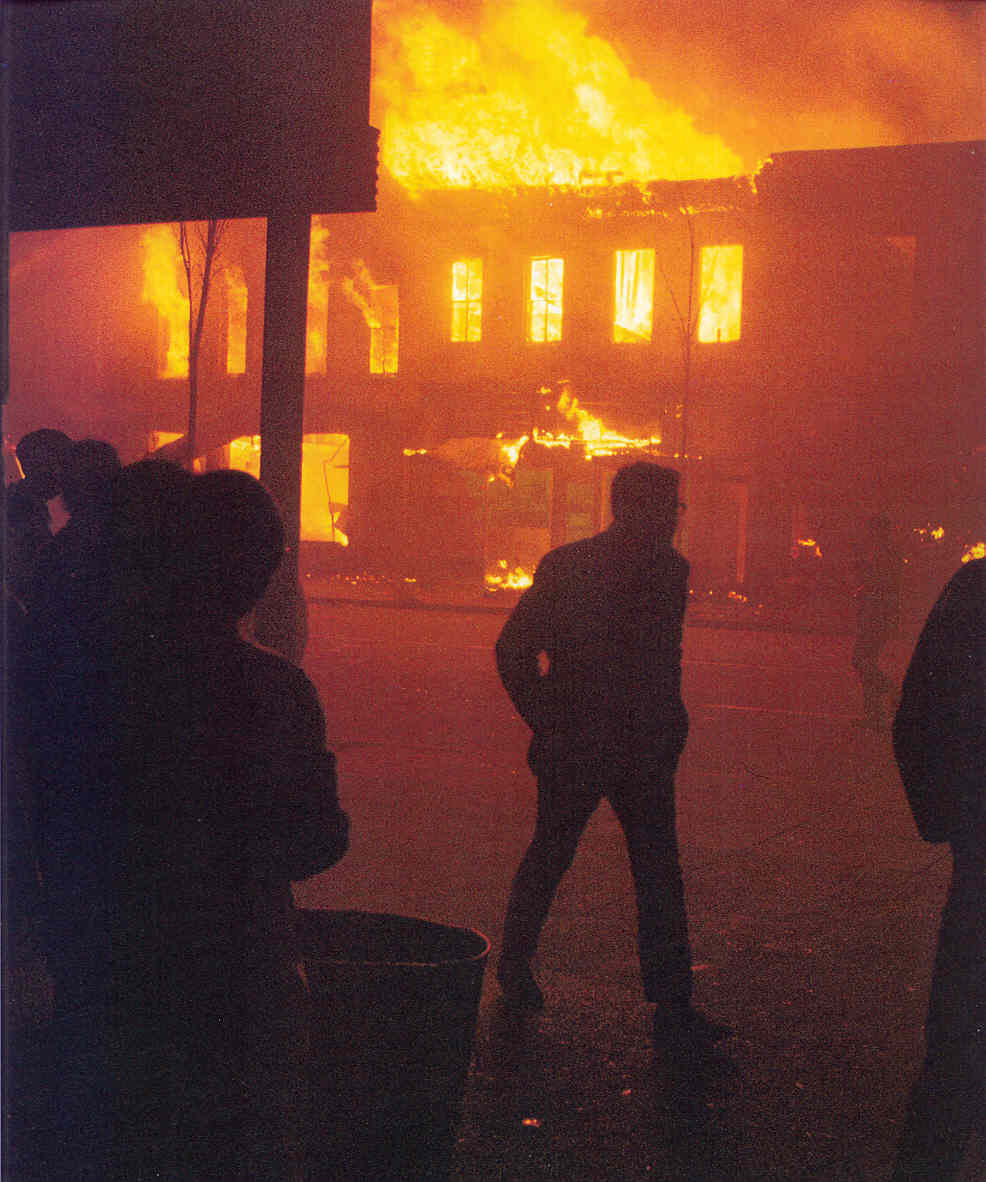

go at some other group, as some kind of great crusade! I saw plenty of

that unfolding in America in the late 1960s.

Or were they really able to take that society to higher things, without

starting a foreign war as a very destructive cheap-shot version of

"pursuing higher things?"

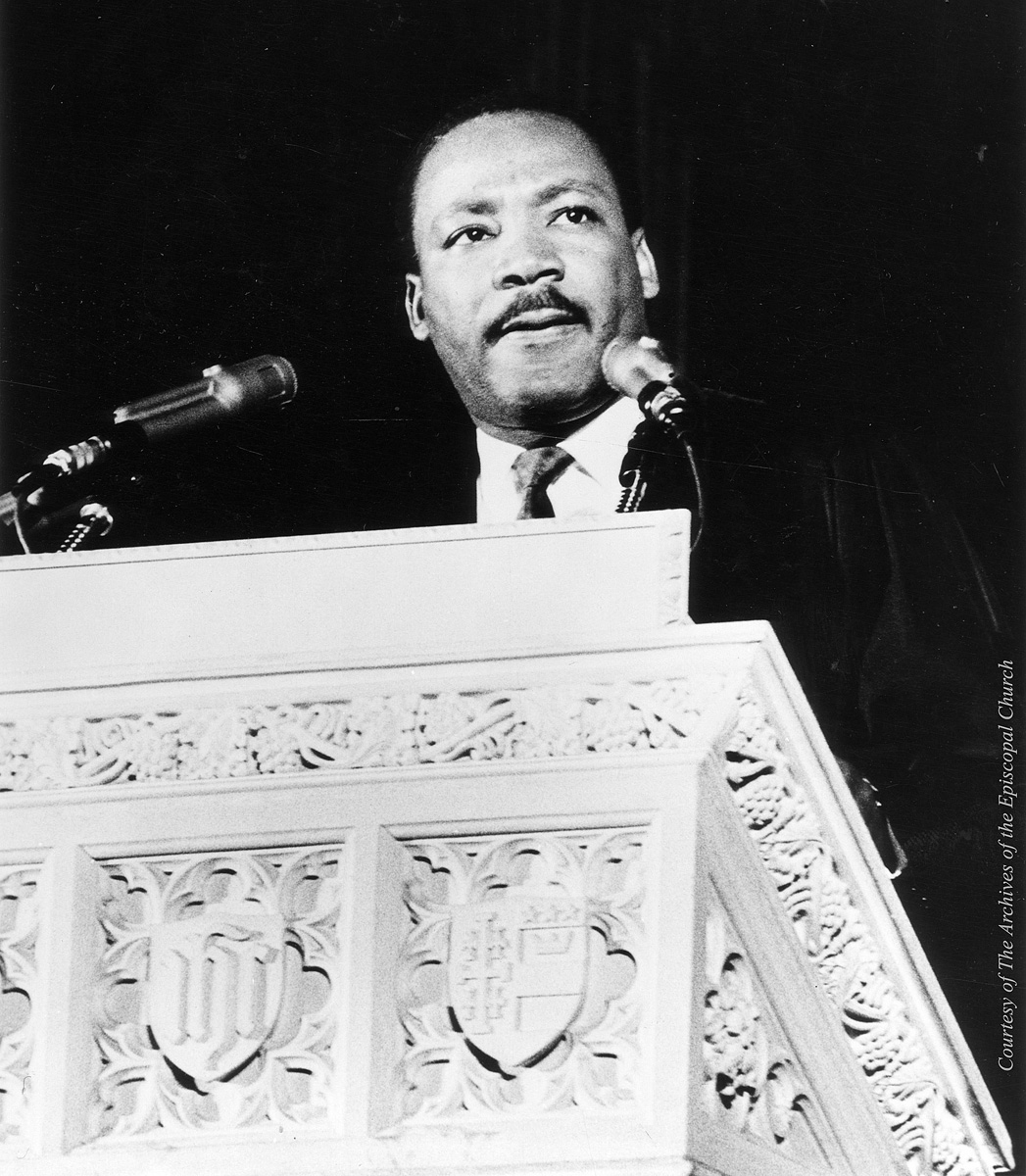

President Kennedy and Dr. King clearly understood things along higher

moral lines and tried to inspire Americans to support those higher

things.

But Johnson did not have the same confidence in the American people,

and tried to put his "higher vision" in place (his "Great Society")

through social programs devised by social specialists and backed up by

government economic policy and ultimately enforced by the law

itself. But turning the challenge over to Washington bureaucrats

was not the same thing as turning the challenge over to the American

people, who were left very passive in this higher reach – with

ironically, the Black community also becoming even more deeply reactive

to "Middle America."

Johnson, also tried to bring the nation to higher national purpose by

taking on the challenge of fighting the spread of Communism in

Southeast Asia. But he really knew very little about the dynamics

that drove Vietnamese society, and turned that country into an even

bigger mess.

Thus tragically, disaster resulted from his efforts, both domestically and overseas.

And I had been in Washington (1963-1968) to see that all unfold!

|

|