|

|

|

CONTENTS  The two distinct cultural motifs shaping colonial America The two distinct cultural motifs shaping colonial America Western culture and the world Western culture and the world Jewish, Greek, and Roman cultural contributions Jewish, Greek, and Roman cultural contributions  Christianity ... it origins Christianity ... it origins Christianity becomes "Romanized" Christianity becomes "Romanized"  But Christianity survives the Roman decline in the West But Christianity survives the Roman decline in the West The Christian "Middle Ages" The Christian "Middle Ages" The breakup of Christendom The breakup of Christendom The Protestant Reformation The Protestant Reformation The impact in England of the Protestant Reformation The impact in England of the Protestant ReformationThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 18-39 ... and also from my work America's Story - A Spiritual Journey © 2021, pages 12-46. |

|

|

It is extremely important to note that from its very outset, English

America laid out both of the two distinct social traditions mentioned

previously. This happened because English America was founded on two

very different reasons for the English to want to come to America.

Conveniently for our analysis, these two distinct social traditions

were based on two different regions along the Atlantic coast of what

was to constitute English America.

The first of these is the Southern or Virginia tradition, first laid out in 1607 with the founding of the English settlement at Jamestown (Virginia). The second of these is the Northern or New England tradition laid out fifteen to twenty years later (1620s and 1630s) in Plymouth and Boston (Massachusetts), Providence (Rhode Island), and Hartford (Connecticut). Both settlements, Virginia and New England – which were quite different from each other in cultural character and consequently in political design as well – were shaped deeply by the two different European social contexts from which they were drawn. Both settlements came out of a long-standing Christian social cultural tradition. But that Christian tradition itself was highly divided, even by war.

The Southern colony of Virginia was profoundly reflective of the feudal system

which, functioning under the direction of the priestly officers of the

Christian Church and a variety of kings, princes, and dukes acting as

defenders of the Christian faith, had for centuries directed a

basically agrarian European society. As a typical feudal society in

which the hard working many were commanded by the leisured,

aristocratic few, Virginia was founded on the secular quest for wealth

and social status measured by the size of someone's landholding and the

number of people working that land for the landowner: the more land

owned and the more servants working the land, the higher the social

status of the landowner.

All of this was considered Christian because the

understanding was that such a hierarchical system was something that

God himself had ordained, from the aristocratic few at the top of this

Christian social order down to the many common laborers, even

permanently indentured (ultimately enslaved) workers at the bottom of

this same order. The key function of the Christian Church was to

morally/spiritually authorize and protect exactly this strict

hierarchical social order against all forces attempting to disintegrate

it.

On the other hand, the Northern colonies of New England were deeply reflective

of the rising urban-industrial society and culture that had been

emerging along Europe's Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Baltic coastlines

... where an ambitious commercial/industrial spirit posed a profound

challenge to Europe's older rural feudal system. In full support of the

Protestant religious reform challenging all of traditional feudal

Europe in the early 1600s, the New England colonists had decided to

take their reform efforts to America, seeking to establish there the

right to live as God directed – not as man, not even kings or bishops,

directed.

The key distinguishing features of this New England social order were 1) the deep sense of equality of all

members of society, because ultimately all people were equal in the

sight of God; 2) the responsibility of everyone to embrace fully the

toil (hard work) in God's vineyard necessary to make this Godly society

succeed; 3) the understanding that those who took the responsibility to

guide this society (its religious and civil officers) were servants –

not owners – of this society, regularly elected to office by its

members (and recalled by them if need be), and therefore not

constituting some permanently privileged social class or group; 4) the

moral and spiritual guidance of each community by means of the careful

examination and presentation by highly educated pastors of God's Word

to that community, their preaching to serve as the social-moral

foundation of this new social order; and 5) the understanding that the

English community they purposely set up in the New World was intended

to be a social model for all the world, demonstrating how it is that

God expects everyone to live.

This dual profile of Virginia and

New England not only divided America into two cultural-spiritual camps

from the very outset of the colonization effort, it would lead the

country in the mid-1800s into the violent conflict we know as our Civil

War (1861-1865). And elements of this same cultural-spiritual divide,

though no longer geographic, grip America even today.

|

|

| America

was not founded outside of some kind of larger social context. In

fact, quite the opposite was the case. Although America seemed to

have been built "from scratch" beginning in the early 1600s, it did so

with a full understanding of the cultural legacy it had inherited from

the motherland back in England, and England's own larger European

context. In fact, it was deeply motivated by the desire to build

in America a much purer form of exactly that very social inheritance,

especially in the setting up of New England. That social inheritance was not universal, but was – in the setting of the larger world and its many different civilizations – quite unique. And that very uniqueness is what we will be looking at in this chapter. The heart of the "Western" social ethic. Westerners, unless they have lived and worked substantially in other non-Western cultures, tend to suppose that what they understand to be true about life is something of a "universal" for all humankind. This is hardly the case. In fact, this naïve supposition has been the source of major problems for Westerners – and for America in particular, ever since it took leadership of Western civilization after World War Two. Because of its development via the Jewish, Greek and Roman experience – synthesized beautifully in the Christian religion – Westerners see life as shaped by deep personal involvement of adventuresome individuals. Western individualism is in fact a key component of Western civilization, found in everything from capitalism, to Darwinism, to Humanism, to modern science, to democracy (and much more). But it is summed up most perfectly in Christianity, which, through the teachings and example of Jesus, makes the bold assumption that we all are potentially sons and daughters of God Himself, divinely empowered individuals able to take on life personally because of this empowerment. There are huge moral and spiritual responsibilities placed on the shoulders of those who rise to this understanding, which could be (even should be) any of us. But we have the wise guidance of holy scripture to help us make the right choices in taking up freely these personal responsibilities. Of course this understanding allows the option of not following such divine guidance, because Westerners are not God's puppets, but instead fully free agents. Indeed it is God Himself who ordained our human nature, wanting us to choose freely to join him in celebrating His awesome Creation. If we did not have the option not to do so, it would cheat the decision to actually do so of its real significance. Westerners, especially recent scientists such as Einstein, Schrödinger, Bohr, Polkinghorne, etc. in fact have made it quite clear that human life exists in the midst of this universal vastness specifically for this purpose: to join the Creator of it all in celebrating with Him (Einstein's "Herr Gott" or "Lord God") the beauty of it all. As far as we know, we are the only part of Creation that is fully aware of its own existence! This indeed is the very purpose of quite conscious or "awake" human life itself. And thus it is that we freely design societies that allow the people themselves to use this special human talent to observe, to learn, to design even their own lives, as they themselves personally choose to do so. Personal "freedom" that allows this dynamic to flourish thus comes to be a Western value of supreme importance. Of course, freedom raises its own problems, because there is at the same time a primal instinct in humans to want to control the world we live in, to remove its obstacles, its complexities, in order to make it more understandable, more predictable, more manageable. And that includes the world of others, because other people can become quite problematic for us. Dominance, even dictatorship, is a possible result of such human impulse. But supposedly, this is why we have Scripture to warn us, to guide us, to keep us within workable social boundaries. Otherwise either pure chaos or pure dictatorship would come from the full use of absolute human freedom. And there are plenty of examples of this in human history, especially in Western history. And some of these are quite recent, in fact even very operative among us today. The Hindu social ethic. Other cultures have gone at life in ways quite different from this Western pattern. For instance, Hinduism, which has long dominated the Indian subcontinent, sees life resulting from what we Westerners might term "fate." All of life is shaped by a cumulative record of actions, good and bad, that result from our behavior. In fact it is this record that shapes our destiny, not just in this life but in lives to come – just as the present has been shaped by the record of human action in previous lives. And how do we come to understand the source of our personal fate? It is clearly shaped by the social position we found ourselves born to. We take on a new life as members of a particular sub-caste or jati (India has thousands of just such different social groups or jatis), a community shaped by very clear rules that will determine our social record (and how well or poorly we perform accordingly), and whether we advance or retreat over the flow of many rebirths to a higher or lower social status. This is a quite compelling social system. There is no room for personal negotiation, no opportunity for an individual to come up against some very serious cosmic judgments that lie beyond his or her control. You must obey, or you suffer. Interestingly you can build a very strong social order on just such an approach to life. The rules of Hinduism are so fixed that Indian society needs no dictator to make the whole thing work. Social responsibility is completely that of the individual Hindu – to obey and prosper – or otherwise suffer, if not in this life at least in the lives to come. When Americans look at India, they see "democracy" in action, or at least that is what they think they are seeing. India indeed has governing institutions quite familiar to Westerners – part of the British inheritance, which Gandhi, the "father" of modern India, himself disliked intensely! He himself as a young man tried very hard to become "English," to escape the fate of being Hindu. But he found that his brown skin was very much a problem in this endeavor to enter fully (in high social standing) in English society. He eventually turned bitterly against things English, but could not bring himself to support the Indian caste system on which Indian society rested. In the end, India came under the industrial modernizer Nehru (and his family) and India managed to move into a world that accepted some of the Western legacy, while keeping the Hindu legacy still intact. Tragically however, it took the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Indians (including Gandhi himself) to make the transition (1947-1948). But India seems to enjoy a quite workable system today. Buddhist Asia. Buddhism was born in India centuries before even Christ entered the picture, as something of a reaction to the inflexible social restrictions of Hinduism. Buddha, as an Indian prince-turned-guru (teacher or prophet), tried to create a social system that would be fairer to those who suffered the most socially, economically and politically from the rigidness of the Hindu system. He failed in this socio-political enterprise. However he did end up discovering a way of escaping the rigid Indian caste system, by simply quieting, even deadening, one's concerns over life's many obstacles. He discovered that a deep spiritual passivity would not only remove the frustrations of this life, but in letting go of the hold of the Hindu social ethic, offer even freedom from the problem of having to be reborn, of having to have another go at life in order to improve a person's place in the scheme of life! No more rebirths meant freedom or Nirvana. But Buddha's Nirvana was a freedom that resulted not from activity (Western style) but from passivity. For a while (several centuries) Buddhism spread widely across India. But theological splits within the religious community, plus the determination of the Hindu priests or Brahmans to retake control of Indian life slowly drove Buddhism from its homeland in India. But by then it had spread eastward into Southeast Asia (Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, etc.), into Nepal and Tibet, and ultimately into China, Korea and Japan. Buddhism provided spiritual comfort to the masses of farmers or peasants across the land as they dealt with the many challenges of nature, of insects, disease, floods, droughts, and raiders and plunderers, all of which so often made life very difficult. This tendency toward passivity also made it easier for certain warlords to take command over their region, some even becoming emperors, rulers able to offer protection against the larger threats to local life. And out of this arrangement, life in Asia could take on civilized ways, as long as emperors were able to carry off their responsibilities and as long as the challenges did not become overwhelming (which they could indeed become from time to time). Democracy was not what the people wanted, or even understood. They simply expected that those that took responsibility for life's larger issues (ones that Buddhism could not take on personally) would do their job. And if so, then Heaven itself would bless the people and the land. They did not ask to be part of the decisional structure. That was the role of the rulers. But they did have their expectations that their world would be served wisely and well by those in charge. Basically this is what guides China today. This is also what Johnson was up against in Vietnam in the 1960s when he tried to encourage the South Vietnamese to take up the responsibilities of democracy, democracy conducted in the same manner that Americans supposedly governed their lives. But Johnson was working entirely outside of the Asian (largely Buddhist) social context, and had no idea at the time of how problematic that would be for him and his grand plans. For instance, when in the early 1960s Buddhist monks took to the streets to protest against outside intrusions into their culture – one monk even burning himself to death – they were not clamoring for democracy, nor for Communism. They just wanted everyone to go away and let them get back to the kind of life they well understood. Islam. Islam is a first-cousin of Christianity, but forged out of a very different social metal than the deeply Westernized Christianity. Muhammad was completely fascinated by Christianity, and thought of himself as actually someone operating along the lines of the Judeo-Christian prophets. But he was Semitic in mentality, meaning, he saw life as a tightly structured social realm. Social authority was necessarily very strict (the desert environment in which he lived offered little room for social error), and very hierarchical. In fact, Islam conveys the meaning not of freedom, but of submission, submission to those standing in authority above you. A son obeyed his father, a father obeyed his clan chief, who in turn obeyed his prince, who in turn obeyed God. And there was also a strong element of religious authority in the mix. In fact, Muhammad's successors (caliphs) carried in their all-important political-social governance both secular and theological authority. Thus to a true Muslim, all this talk of Westerners about personal freedom seems to derive from Satan himself, for such freedom would, in the thinking of a typical Muslim, be entirely disruptive of the Muslim social order. Indeed, the efforts of Westerners to get the Islamic world to take on Western democratic ways is about as appealing to "true" Muslims as, for instance, Communism is to most Americans. It's just not going to happen. The Muslim world has its own ways of governance – patterns established long ago – and still dictated by the commands of the Qur'an (Islam's holy book), a grand work derived from the supposedly divinely-inspired pronouncements of Muhammad – and thus not negotiable! Period. |

|

|

As with all cultures, Western

or Christian culture is a unique blend of various contributing

sub-cultures, ones however which combined around the idea of the

importance of the sovereignty of the individual. This is partly a

Jewish idea, partly a Greek idea, and partly a Roman idea, into which

Jesus came to sum up the idea of the sovereign individual. Each

of these sub-cultures helped to develop that key idea. And so it

would profit us greatly in coming to an understanding of the deeper

character of our Western civilization if we took a closer look at each

of these contributing sub-cultures. And it is most logical to

start with the earliest, and in a way the most determinative, of these

ancient sources: Judaism. But in becoming a

rich and successful people, the Israelites soon fell away from their

devotion to Yahweh, who then abandoned them to the folly of their own

political planning and operating. They became reckless in their

messing with the growing powers of the Egyptian Empire to the south of

them and the Assyrian Empire to the East of them. If they had

been wise, they would have stayed out of the growing struggles between

these two neighboring empires, for this was not God's plan for

them. And they had prophets who warned them of the dangers of

such foolish involvement in the larger political battles going on at

the time. Eventually Israel got itself in trouble with Assyria,

and the cruel Assyrians marched ten of the twelve tribes of Israel off

to captivity, where they scattered the Israelites among the peoples of

their empire, and soon much of the Israelite identity simply dissolved,

never to recover again. However, the

Southern Israelite kingdom, basically made up of the tribe of Judah

(thus the Jews) had more wisely stayed out of these political doings,

and Assyria left them alone. But such wisdom did not pass on (as

so often happens) to a new generation of Jews, who got mixed up in the

struggles between Egypt and the newly rising power of Babylon, which

had just succeeded in overthrowing Assyrian power. Finally now it

was the Jews turn – at least their leading citizens – to be carted off

to Babylon. But by the grace of

God, the Babylonians let the Jews at least remain together as a

community in captivity. Thus the Jewish identity was not

lost. But still, as a people's religion defined the very nature

of their societies back then (and still today) they were in a bit of a

quandary. The Babylonians would not let them build in Babylon a

temple to their god Yahweh (the one in Jerusalem in fact had just been

torn down by the Babylonians), and thus it seemed at first that there

would be no way for those relocated to Babylon to hold onto to their

unique social identity. But they did have

one very precious item that they could cling to, which would serve to

keep them mindful of their existence as a distinct people: their

own tribal narrative – a history of their tribal ancestors and their

relations with their god Yahweh, a story which reached all the way back

to what they understood as the very beginning of humankind

itself. There in Babylon incredible religious scholarship would

develop under the guidance – not of the (unemployed) temple priests,

but instead by religious teachers or rabbis, who collected this

far-reaching narrative and turned it into a piece of holy writing,

something that the members of the Jewish community could study,

meditate on, and be guided by socially. And they could do so

wherever they found themselves, even there in Babylon. All they

needed was some kind of community center, the synagogue, where they

could gather locally on a regular basis (at least weekly on the

Sabbath) and hear a teaching – usually some form of commentary on their

holy Scriptures – presented by their teachers (rabbis) and elders. And it was all very

democratic, in the way that all young men were expected to demonstrate

– as a rite of passage into manhood – the ability to perform this kind

of rabbinical Biblical study and teaching. In a way it was an

early version of the "priesthood of all believers"! This also gave the

Jews the idea that they served the interests of God in the broader

realm of humankind, for they were led now to understand that God was

not just a Jewish God, but was the God of all people, Babylonians,

Egyptians, and everyone else. And as a special covenant-people of

God's own choosing, they had the larger responsibility of bringing

their awareness of God's role in life to all the people, non-Jews as

well as Jews. Thus they became quite active in Babylonian

affairs, as a "people of God," a "Light to the Nations." Eventually the

Persians conquered the Babylonians, and allowed the Jews then to return

to their lands in Israel. But most chose to remain behind in

Babylon and continue their special lives there (Babylon and then Persia

would continue to serve as a key center of Jewish scholarship and

religious activity). Those that did return to Jerusalem naturally

rebuilt their Temple. However, they did not let go of the Jewish

spiritual practices developed during their Babylonian captivity, but

instead kept Jewish life active around the local synagogues, under the

leadership of the rabbinical scholars. And that would continue

all the way down to the time of the Roman Empire, and the arrival of

Jesus. In fact, it still continues to this day, wherever the Jews

find themselves in this world of ours! Most Americans know

that the idea of democracy was a political legacy given Western

Civilization by the ancient Greeks (500s-300s BC). Actually it

was practiced widely around the ancient world, and not just in Greece –

developed out of the need of tribal peoples, generally everywhere, to

consult with clan or household elders whenever an important decision

affecting the tribe had to be made: when to hunt, when to go to war,

when to make a physical move. It was necessary to get every clan,

every household of the tribe on board with the decision – for unity of

purpose was essential to the survival of the tribe. Thus

democratic consultations would continue until some kind of general

agreement was possible prior to taking action with respect to the event

in question. Thus it was that the

very ancient or early city-state Athens was quite reliant on the

democratic process of holding meetings to discuss common matters – and

have an affirmative vote from the participants in order to move things

forward. But when the

population of Athens began to grow, participation of all Athenian

citizens in such decisions became problematic. There simply were

too many people involved to conduct such business in an orderly

fashion. Consequently, small groups of people – especially ones

that could claim a longer line of Athenian ancestry – would tend to

take control, turning themselves into something of a ruling

class. And the xenoi (foreigners) not born of Athenian ancestry,

who were even more numerous than the Athenian citizenry, had no place

at all in this process, not to mention the slaves, who outnumbered even

the xenoi. Unsurprisingly, as

class distinctions developed, so did class conflicts. Several

efforts were made to improve the democratic process (a toughening of

political requirements under Draco (thus the term "Draconian,"

something very brutal as social measures typically go), countered a

generation later by Solon – who attempted a fairer distribution of

responsibilities and rewards. However, this did not make a huge

difference in the Athenian political lineup. Finally, in

reaction to Peisistratus' tyrannical rule (a "tyrant" was actually

originally a strong-handed defender of the rights of the poor) and the

rising danger of mounting Persian power to the East, the popular

politician Cleisthenes was led to reform the constitution by simply

re-classifying the Athenians into ten residential or neighborhood

"tribes" and having these tribal districts represented at the Assembly

by citizens chosen by lot. Fair enough! And thus it was

that Athens affirmed itself as a "representative" democracy. For a time this

reform, plus the mounting danger of an aggressive Persia taking control

in the eastern Greek lands of Ionia, brought unity to the Athenian

population, bringing even the Greek city-states to amazing unity under

Athenian leadership. It even forced Athens' chief political rival

in Greece, Sparta, to cooperate with Athens militarily. And this

unity finally allowed the Greeks to defeat the Persians at Marathon

(490 BC) and Salamis (480 BC). From this point on

(the mid-400s BC) Athens took on the position as Greece's leading

city-state, particularly when other city-states agreed to send funding

to Athens to support the unified Greek defenses of the new Delian

League against a resurgent Persia. And this marked the

"Golden Age" of Athens, under the capable political leadership of

Pericles (excellent orator, statesman and general) during the period

from the mid-400s BC to his death in 429 BC, a time in which Athens was

also producing the historical insights of Herodotus (to about 424 BC),

the creative works of the dramatists Euripides and Sophocles (to 406

and 405 BC respectively) and the outstanding philosophy of Socrates (to

his death in 399 BC). But moral problems

within Athens itself had begun to mount during that same period.

Peace had brought not democratic nobility of spirit, but a new

greediness, stoked by the political self-interests of a series of

leading Assembly speakers, clever Sophists or "wise ones," able to

convince – through the most clever use of "reason" – the

representatives of the people to do the most unwise, most

self-destructive things, merely because it played to the interests of

one or another of these "demagogues." For instance, the

demagogues led the Assembly to the decision to use the money sent by

the other city-states to Athens for Greek mutual defense instead to

simply beautify Athens itself (new buildings, improved streets, grand

statuary, etc.), despite the protests raised by its Greek allies.

Ultimately these other city-states would look to Sparta to champion

their cause against an increasingly greedy Athens, and ugly war

resulted. How stupidly selfish

Athenian democracy had become. And the Athenian representatives

would also foolishly ostracize (expelling for ten years) Athens' very

best military leaders – actions inspired by jealous Assembly

speakers. What was this democratic body thinking? All

of this helped lead to Athens' ultimate defeat in a series of

Peloponnesian Wars (the second half of the 400s BC). Thankfully Sparta

ignored the demands of its city-state allies (Thebes, Corinth and

others) to enslave the defeated Athenian population, but resolved

instead simply to tear down Athens' city walls, leaving the city

defenseless militarily from that point on (404 BC). This was the

beginning of the end of Athenian greatness. But the foolishness of Athens' democratic Assembly did not end there. In 399 BC, the

wisest philosopher of the ancient world, Socrates, was voted the death

penalty by the democratic Assembly – because he annoyed Assembly

speakers by calling into question the wisdom of their words and

behavior. In sum, democracy Athenian-style had led that society down a very self-destructive road. Socrates' pupil

Plato tried to find a better approach to political wisdom by developing

in a key philosophical work, Politeia (commonly known by its Latin

name, Republic) his own idea of what a well-run society should look

like. But the success of such a venture depended entirely on the

wisdom of the leading politician, not the wisdom of the people (which

Plato doubted was obtainable anyway). This would be the

beginning of the tendency of intellectuals to design from their desks

beautiful societies, or "utopias" (a Greek word meaning literally

"nowhere"!) – built entirely on their own powers of rational planning,

and not on the basis of actual human experience (which tends to be not

very pretty much of the time). But Plato would have

the rare opportunity as an intellectual to discover how well his ideas

actually worked, when he was invited by the young tyrant of Syracuse,

Dion, to put his philosophy to work there. The end result when

Plato faced political reality was total disaster for Syracuse (20 years

of chaos under the social breakdown that his experiment ultimately

produced) and Plato's own arrest, imprisonment and sale into slavery,

which he was finally purchased out of by a sympathetic fellow

philosopher. Plato's own student,

Aristotle, was more cautious in his approach to political design,

actually studying historically various patterns of social

governance. In his famous works, Politics, he stated that on the

basis of his research, the measure of good or bad in a society and its

government appeared to depend not on the constitutional form of

government itself – whether a government was made up of one (as in a

monarchy) or a few (as in an aristocracy) or the many (as in a

democracy) – that is, not by how many ruled, but by how morally they

ruled. A rule of one could be good – or bad – depending on the

moral quality of the ruler. A rule of the many could be good – or

bad – as for instance a rule by an enlightened citizenry would be

considered good, whereas rule by a frenzied mob would most definitely

be viewed as some perverse form of popular tyranny. Thus to

Aristotle, "good" or "bad" depended not on how many ruled but how well

the society was ruled by its own high moral standards. Failure to

hold to its foundational standards would soon enough bring any society

to ruin. As we shall see

further on in this narrative, the Founding Fathers of the American

Constitution (1787) were college men, back when college or university

education meant principally a study of the humanities (philosophy,

theology, history, law, and the social sciences). Thus they were

very aware of both the political history of ancient Greece, and the

philosophy of the Greeks, especially Plato and Aristotle. We

shall see more of how this influenced deeply their decision as to how

to build a new Federal system uniting the thirteen newly independent

American states. Full democracy was not their goal. Democracy was

included as part of the dynamic. But they attempted to put it

under the considerable restraint of a constitutional "checks and

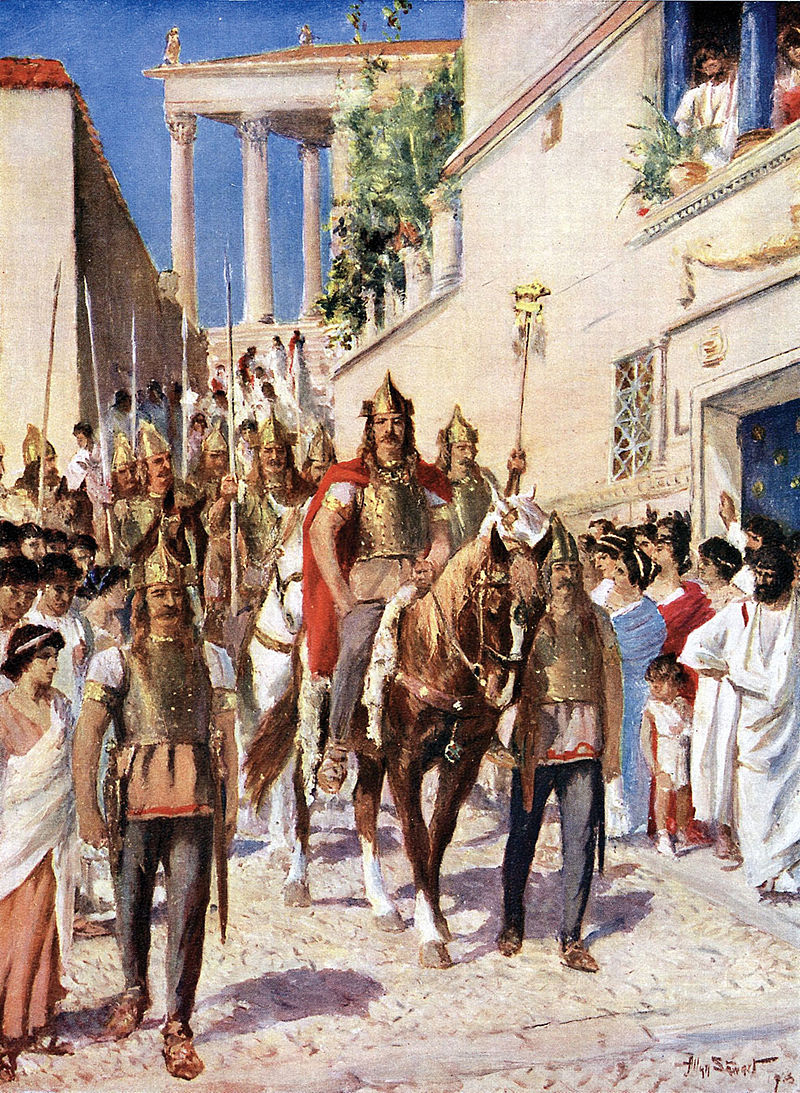

balances" system. More about that later. Most amazingly,

Alexander proved to be as much a leader as his father. He was

able finally to assemble the Greeks into some kind of united community,

to take on the powerful Persians directly – in Persian territory itself

this time. There would be no more just sitting passively waiting to

fend off another Persian assault, as had been the pattern

previously. Alexander intended to go at the Persians in their own

world. He first captured

the lands bordering the Eastern Mediterranean, including even

Egypt. He then swung his army eastward and crushed the Persians'

own efforts at self-defense in 331 BC. But Alexander had a

roll going, and kept on conquering, deeper into central Asia, and even

down into the Indus River valley. But his soldiers were at this

point exhausted and wanted to go home, or at least back to Babylon, the

former Persian capital, but now theirs as well. Thus he turned

around (however, losing half his men trying to get across the Baluchi

Desert). But back in Babylon, Alexander was himself soon to die

(323 BC), probably his death resulting simply from sheer exhaustion. Alexander thus left

a huge Greek legacy for his successors to deal with (they ultimately

split Alexander's huge empire into a number of smaller empires).

And it left a lasting Greek cultural imprint on the entire region, not

only in the Eastern Mediterranean but even into the Mesopotamian lands

(principally today's Iraq) and large sections of central Asia. The importance to

Americans of this Alexandrian legacy is that Greek culture was so

dominant in the times of Jesus and the first century church that all of

Christianity's foundational writings were done in Greek, not the local

Semitic language (Hebrew and Aramaic) of the lands where Christianity

was birthed, or even the Latin of the then-dominant Roman Empire. And for such an

understanding, we Americans are deeply indebted to the Romans, for it

is from them that the concept originated. Under the Romans, their

government or "republic" was originally designed to be a government not

of human wills, whether the will of one person or even the many.

The Roman Republic was intended to be a government of laws, a permanent

body of rules that would describe the order that all Romans were to

live and thrive under – an unshakeable legal order that would continue

forward in a precisely-defined way regardless of whatever personalities

played their assigned parts in this order. A Republic was

intended to be a system of fundamental or unchanging constitutional

laws – not a system governed by the whims of human ambition and

personal political interest, no matter how "rational" these whims might

claim to be. And these laws were supposedly eternally

valid, because they found themselves detailed on 12 bronze tablets (450

BC) posted in the Roman Forum (central market and religious center) for

all to see. And all Romans knew these laws well. This was the key to

Rome's early success in its expansion across Italy, and then across the

Mediterranean world (and Europe north of the Alps as well).

Unlike tribes and nations that have a very hard time bringing conquered

peoples into their social order as fellow members (choosing instead to

enslave them or butcher them on the spot), the Romans offered

participation of those they recently conquered in their society as full

members, provided they were willing to come under Roman law and live

accordingly as Roman citizens. That was not only fair, it was

powerfully effective in developing Rome's wide-spread multi-ethnic

republic. And it created a

powerfully effective socio-economic order. Given their legalistic

mindset, Romans almost instinctively organized the world around them

physically and materially as they conquered it, building roads (still

standing today in many places) to provide rapid communication, troop

movement and ultimately commerce connecting the Roman center to its

outlying territories. Wherever they conquered they planted

military camps (naturally on a perfectly uniform grid pattern!), which

became the heart of new commercial towns which quickly grew up around

these garrisons. They cleared the seas of pirates and kept

marauding tribal raiders from central and east Europe closed out beyond

a well-defended line running from the Rhine River in Germany to the

Danube in the Balkan Peninsula. Consequently, the Mediterranean world

that Rome had "conquered" experienced an unprecedented peace and

prosperity, one that made Rome the very model of civilization itself to

millions of people. Over time, but

particularly during the wars with the Carthaginians (the three Punic

Wars from the mid-200 BC to the mid-100s BC), the Roman Senate had

become the center of all Roman power. It was a club of old Roman

families (the "patricians") joined by a select group of "commoners"

(the "plebeians") of recently acquired wealth, which closed its ranks

against the rest of the Roman common or plebeian citizenry. In

short, the Senate had turned itself into a ruling oligarchy.

Meanwhile rising taxes necessitated by ongoing war, and competition

from the growing amount of slave labor acquired in these wars, were

bringing the more middle-class Roman plebeians to ruin. And yet real

Roman power, especially the power of the Roman military, was built on

the loyal services of these commoners as citizen-soldiers.

Something drastic needed to be done to save Rome from collapse or

revolution. Thus as was the case

for Athens, efforts were undertaken by leading Roman citizens to reform

the system, opening up bitter debate as to exactly how that was to

work. "Reform" invites new forms of reasoning into the older

legal order, reasoning which can go most any way, or at least in the

way of the most powerful of the social groupings within society.

In short, the ancient Roman Constitution proved to be not quite as

permanent or unchanging as a body of laws. Social problems thus

merely increased as various identity groups wielded reason against each

other as Rome sought to upgrade the now-changing constitution.

Tragically, identity politics was overwhelming the constitutional

republic. The Gracchi

brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, as Tribunes (Rome's political officers

representing the interests of the commoner plebeians), attempted

reforms in favor of the plebeians (133-121 BC), which were blocked by a

jealous Senate. The brothers were either clubbed to death by a mob or

forced into suicide in advance of a mob, stirred to action by the

Senate. This brought forward

the military leader Marius (108-100 BC) who tried to use his power to

clean out the corruption in both the military and the massively

expanding Roman bureaucracy. But in the end, he was unable to

stop the Roman fall into deeper "Social War." This in turn led

General Sulla to march his troops into Rome (a highly illegal act),

designed to undercut the plebeian reform party and strengthen the

position of the Senate. Thus Rome came under the first of its

military dictators (82-79 BC) or "emperors" (from the Latin imperator

or military commander). But the chaos only

deepened, especially with Spartacus's slave uprising (73-71 BC).

At this point, the Senate looked completely to the Roman military to

save Roman society. This resulted in the selection of three

generals – Crassus, Caesar and Pompey – to bring Rome back under

control. But instead, it simply put Rome through the process of a

growing political competition among these three military giants.

One last effort was made – by Cicero – to bring Rome back under

constitutional rule. But getting nowhere, Cicero retired from

politics, the last significant spokesman for Roman Republicanism.

Finally, with Caesar coming out on top in the competition among the

generals – by marching his troops on Rome in 49 BC – Rome now found

itself under full military rule. The Republic had just begun its

conversion from Republic to Empire (imperator-ruled). And it would be

Caesar's adopted-son (actually nephew) Octavian "Augustus" Caesar who

would complete the conversion, as he tightened up Roman "Republican"

society just as a general would tighten the ranks of his army.

His absolute hold over Roman society did finally bring about

much-needed social order. But it also ended forever the role of

the Roman commoners in determining the shape and behavior of their

society. Rome was now ruled "from the top down" by a rigidly organized

Roman military imperium. The "Republic" now existed in name only. For a while this

looked as if it had been exactly the right development needed by a

mighty Rome. And this "for a while" was set in place by indeed a

number of very capable Roman emperors – Octavian Caesar, Tiberius,

Vespasian, Domitian, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and finally Marcus

Aurelius – who governed the Empire during most of the first two

centuries of the Christian era. But from the death

of Marcus Aurelius in 180 onward, Rome (or its military legions that

actually did the selection of Rome's imperial leadership) seemed unable

to come up with talented leadership. To a great extent this was

caused by the deep infighting that went on among the legions as one or

another legion would promote its own general as Rome's new

emperor. The situation got so bad that in a 50-year period

(running from 235 to 285), constant overthrow or assassinations of

emperors (25 in total!) going on within the higher ranks of the

military caused Rome to tumble into deep moral corruption and social

chaos. And thus did Rome begin its fall from greatness – to the

status of its Republic being no more than a fond memory, actually a

tragic memory. |

|

|

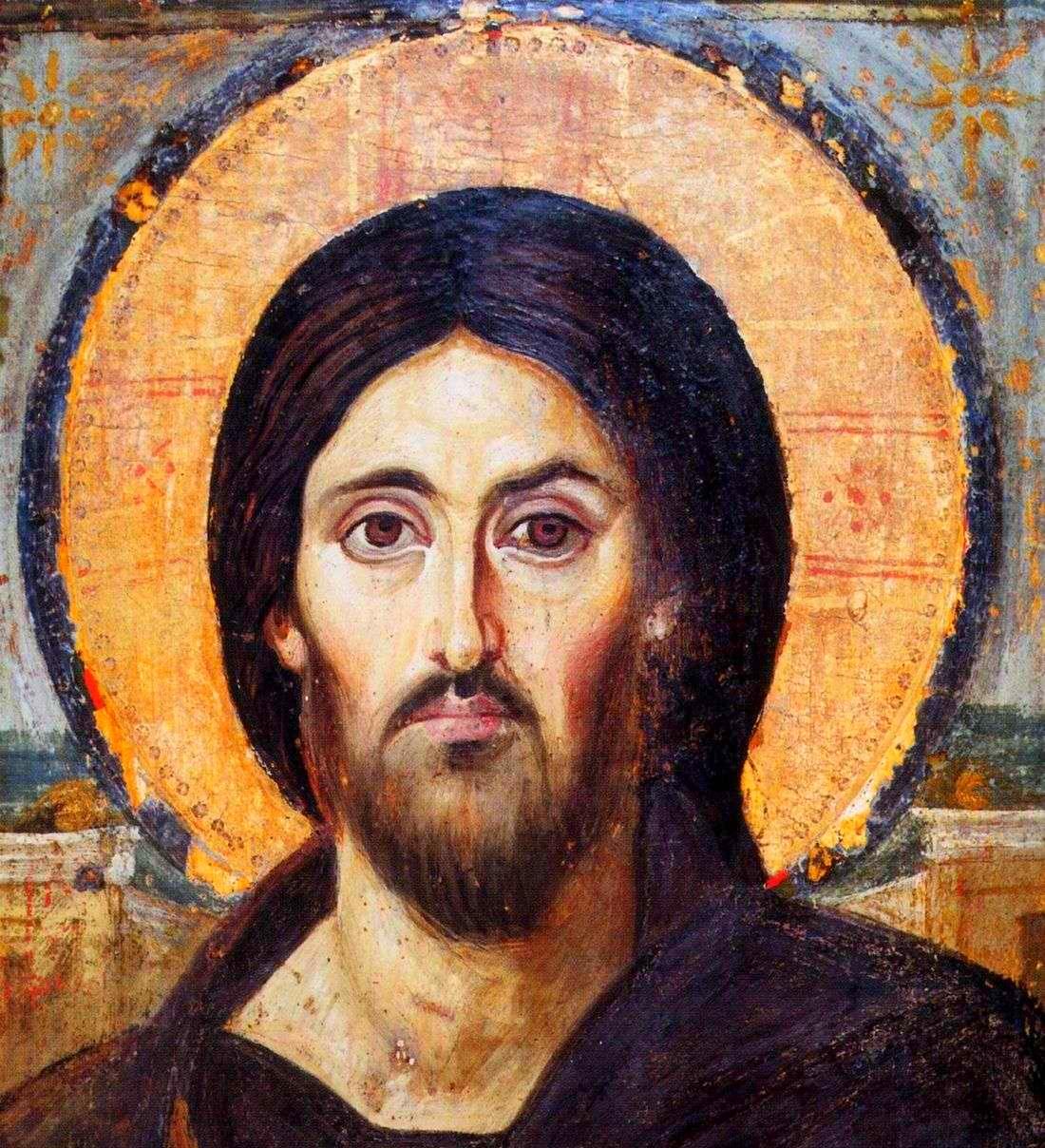

The critical importance of America's own Christian roots.

But, of all the different social legacies that went into shaping

American society – Jewish, Greek, Roman and, Christianity – it has been

the last of this list, Christianity, that served ultimately as the

foundational element of American society. It was Christianity

and its accompanying social order that birthed and then developed

English America politically, economically, socially, etc. – serving as

America's moral-spiritual foundations on which a new American society

was built, even many generations before the establishment of the

American Federal Republic in 1787. In fact that

broadness of his spiritual reach was the very heart of his ministry,

the demonstration that God as Father was not interested in the various

ways that we humans divide the surrounding world into various identity

groups, ones to be loved and supported and those to be despised and

forcefully rejected. And Jesus's wide-ranging realm of love

included not only tax collectors and women of questionable repute

(major sinners in the Jewish social scheme), but also foreigners such

as a Roman centurion and the despised Samaritans, and even

lepers. And he also had a high regard for the importance of

children, a group of small beings who had not yet earned the right of

high regard or social respect in the thinking of the time (and maybe

still even today). Furthermore, he drew into his closest circle

of friends people of no greater status than that of fishermen. In short, Jesus was

no practitioner of identity politics. Quite the opposite.

His ministry was a clear demonstration of the fact that our Heavenly

Father made no such human distinctions in his love of humankind.

That was man's own particular failing: to judge others on the

basis of where these others stood in the comparative realm of identity

politics. Of course people of

reason (they existed back then no less than they do in today's

"scientific" culture) were disbelieving and even hostile to such

demonstrations of Jesus's authority, which he assured others was also –

through the simple power of faith in God as Father – within their reach

as well. But then hundreds of

his followers were most certain that he returned (briefly, for 40 days

or so) from the grave and again taught them his gospel (good news)

message before being taken up to Heaven to join the Father at God's

right hand – and by doing so, releasing the Holy Spirit to come among

the people (on the day of Pentecost) in order to continue the work

themselves that Jesus had started. It is ironic that

the Roman device, the cross – that was intended to force the most

humiliating death as possible on a criminal – would become itself the

very symbol of Christianity. This is because Jesus's death on the

cross was understood by his followers to be an act of cosmic

significance: the blood sacrifice or sin-offering required by the

power of Heaven as the price for entry into eternity. But Jesus

himself was without sin, and so the sins he was paying for in his

self-sacrifice on the cross were not his own. Instead the sins

being paid for by the cross were in fact the sins of the entire range

of humanity. But how could one

man's sacrifice be sufficient to pay for the sins of all

humankind? Actually, Jesus was ultimately understood to be not

just a mere man – but was fully divine – and thus able, as God himself,

to offer himself in sacrifice for the sins of the world. A very loving

God had, in essence, offered himself through his Son as the payment for

the sins of all mankind – at least for those, anyway, that were willing

to put themselves under such divine grace and receive, at the foot of

Christ's cross, God's full forgiveness. Furthermore, in doing so,

they also received a new, powerful life from the hand of God – without

being in any way specially deserving of such favor. In this new

life they would live by and through the power of God's own Holy Spirit,

to help them take on the challenges of life – including even the

challenges presented by their own moral frailties. And they would

continue to be fully empowered to meet the particular challenges

presented to them individually – and jointly (as members of a Christian

society) – until they were to draw their last breath, and at that

point, when their work on earth was done, join their Heavenly Father in

eternal paradise. Trinitarianism.

This idea of a loving Heavenly Father, sacrificing on the cross his own

divine Son for the sins of the world, and then empowering those who

accepted for themselves this act of divine forgiveness with the gift of

God's own Holy Spirit – all of this came together as a key belief

system known as Trinitarianism: a single God in three "persons" –

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Those that could not

or would not rise above the idea of earning moral merits through one’s

own good works argued that Trinitarianism sounded like merely another

version of Dionysian Greek religion or philosophy. Indeed,

members of the Roman world who lived in the predominantly Greek

cultural areas of the Empire were more able to understand and embrace

Trinitarianism. But those of the Semitic world of Syria,

Palestine and Arabia, for instance, refused to embrace Trinitarianism

because it did not conform well to their cultural understanding of

moral behavior and social obligation. But this would also include many

German tribes north of the Roman borders, who did come to accept

Christianity, but also only of the Unitarian variety Ultimately, as

Unitarian Christians, they understood Jesus as a fully human creature –

not another form of God while on earth. To Unitarians, Jesus was a

human without sin to be sure, which made him a perfect moral example

worthy of complete devotion by others – one indeed so perfect in

behavior that at his death he was raised in heaven to sit at the right

hand of God as God's favored Son. And as far as the notion of an

assisting Holy Spirit – Unitarianism found no place in its

understanding to include such a concept. That was way too Greek for a

Semitic or Germanic mind to grasp. Trinitarianism

versus Unitarianism would remain an ideological tension that would

reach through the long history of Christianity and its impact on the

larger world – even down to today. Efforts were soon

made to bring together for study various narratives about Jesus' life

and ministry (the gospels) – plus letters circulated among the various

churches written by key Christian leaders advising them on the

Christian life, many of these letters written by the Jewish convert,

Paul (formerly Saul). Thus was formed the foundations of the

Christian New Testament, the second part of the Christian Bible,

following the longer Jewish or Old Testament portion of the

Bible. Such writing served not only as the central document that

described Christian life in the years of Christ and immediately

thereafter – but also as a social model instructive for Christians at

all times and for all generations. But ironically,

Christian martyrdom merely became an even more-powerful social force

spreading within the Empire – because of the very quiet bravery of

Christian martyrs undergoing such cruel Roman death. Romans grew

increasingly impressed with Christianity's ability to give its

followers such incredible personal moral and spiritual strength, even

in the face of a most terrible death. Christian morality stood

out glowingly in high contrast to the obvious moral collapse going on

within a darkening Roman Secular/Materialistic imperialist culture.2

1Today

we would term their well-structured universe as one that was

"scientifically ordered." Jesus seemed not to be limited in

his thinking and behavior by such "science."

|

|

|

At the time,

Christianity was having a huge impact on the Roman Empire, so much so

that the Emperor prior to Constantine, Diocletian, had conducted one of

the cruelest efforts to eliminate Christianity (thereby supposedly

bringing Rome back to good order), but had succeeded no more than the

emperors before him. Then when he died, four imperators competed

for the position as grand ruler of the Roman Empire. In any case, it

would be another ten years before his sole claim to emperorship would

be completed. But nonetheless, in conjunction with an imperial

ally, Licinius, Constantine the next year (313) issued the Edict of

Milan, ending all further persecution of Christianity. Indeed Constantine

even took for himself the title pontifex maximus, making himself also

the religious head of the Roman Empire, and as such began to reorganize

the Christian religion, Roman style. He called conferences with

the bishops or Christian leaders to clear up the clutter of three

centuries of unsupervised religious development, by clarifying the

doctrines (or "creeds" or "confessions"), deciding which of the

considerable body of Christian writings were to be officially

authorized as "canonical," and by developing a huge, bureaucratic

ecclesiastical (church) structure to supervise the life of this

religious community, whose religion had now officially become the

moral-spiritual underpinning of Constantine's Empire. Indeed, before that same century (the 300s) was finished,

subsequent Christian emperors would see that anything that did not fit

into a precise or legalistic definition of Christianity would be

rejected, and ultimately, Roman style, even be suppressed. So it was

indeed that Christianity, under imperial sponsorship, now itself became

the persecutor of any religious deviants within the newly Christian

Roman Empire.

And thus it was that the Christian faith, which

had started out as the source of strength offered the common Roman

citizen in an increasingly depersonalized Roman Republic run by

military authorities no longer personally accountable to the Roman

citizenry, was subsequently stripped of its democratic roots, and

itself became part of the highly authoritarian Roman imperial realm.

However, at the same time, the masses

rather naturally still held close to their hearts certain aspects of traditional pagan

Roman religion – as well as a deep reverence for the Earth Mother cults

that had been brought in earlier from the East along with Christianity.

With the authorities having now outlawed the religious practices in

which the little people once looked for assistance to the patron gods

of old, pagan deities that once presided over family matters, business

matters, travel issues, romance issues, etc., the little people found

that by appealing instead to famous Christian saints, reputed to

possess the same supportive powers as the former pagan gods, they could

satisfy their spiritual-religious hunger. They thus now prayed to the

saints rather than to the old pagan deities for their blessings. There

was nothing Biblical about any of this (this idea did not originate

from Jesus's own teachings, nor those of his original disciples). Yet

the Christian authorities let such worship of the saints stand, because

it seemed to satisfy everyone and seemed somehow to qualify even as

proper Christian practice.

Likewise, Jesus seemed to slip

away from the grasp of the little people as he became the friend of

emperors, Jesus's primary role now being to certify the rule of

imperial candidates by Jesus's own personal endorsement from Heaven.

That is, Jesus was now Christus Rex (Christ the King), the friend of

the emperors, and too lofty to be approached as personal friend and

savior by mere commoners. |

|

|

Nonetheless a series of

talented Christian Bishops of Rome, who remained behind in the ancient

capital city, continued to command considerable respect within the

Western Christian community – and slowly came to be recognized as the

head of the Christian Church in the Latin West – eventually gaining the

title "Pope," meaning something like Father – but Father (Papa) above

all other priestly Fathers! Especially notable among these popes were

Leo I (pope, 440-461) and Gregory I (pope, 590-604), who managed to

preserve and strengthen what little remained of Roman or Latin

moral-cultural order in the West. Indeed, the church of Rome

not only survived the Germanic impact but converted some of the most

important tribes to Trinitarian Christianity5 and restored the city of

Rome to a position of some degree of religious cultural importance – at

least within the West itself. And there was the British

monk, Patrick, who brought Trinitarian Christianity to neighboring

Druid Ireland in the early to mid-400s. In Patrick's 30-year mission to

the Irish, he established over 300 churches and he baptized over 120

thousand Irishmen. In turn the converted Irish would soon themselves

become Christian missionaries to the Germanic and other Celtic tribes

to the East of them, most notably: Columba (mid-to-late 500s) to

Scotland; Columban (late-500s) to the Burgundians, the Alemanni and

Celtic Gauls on the European continent; and Aidan (mid-600s) to the

Angles, Mercians and East Saxons of Britain. And there were other such

missionaries, monks and priests who acquitted themselves quite

honorably along vital moral-cultural lines, especially once the

monastic movement had been disciplined by Benedict (early 500s), whose

monastic rule was widely honored throughout the West. These monks were

sent out among the Germanic tribes to convert them not only to the

Christian religion but also to the Roman Catholic political-religious

order that accompanied that religion. In many cases the effort by

monks pointed only to the first part of the program: the saving of

souls. But the popes had more of the second part of the deal in mind.

Ultimately tribes had to

decide where they belonged in the Christian program, on their own as

autonomous Christian tribes, or as components of the larger Western

Christian or Roman Catholic community. Thus, for instance, in 664, a

religious council or "synod" gathered at Whitby (north central

England), where the majority of the delegates voted to end the

self-supporting religious life in England introduced by the Irish monks

who had originally brought Christianity to the kingdom The Synod

decided instead to bring the Northumbrian tribe or kingdom within the

religious realm (and its particular Latin rites) overseen by the Pope

at Rome.

5Some

of these tribes, particularly the Goths, were already Christian, though

Unitarian or "Arian" thanks to the missionary effort of Ulfilas and the

leadership of the Gothic chieftain Fritigern in the 300s; Rome was

"Trinitarian" and thus looked on these tribesmen as not yet fully

Christian, and thus in the need of conversion.

|

|

|

to Feudal (or Dynastic) Society Then in the late 700s, Europe underwent a dramatic transformation as Charles, King of the Franks, better known to us today as Charles the Great or Charlemagne, came into the European political picture. Charlemagne not only inherited the title of King of the Franks from his father, Pepin the Short (himself son of the powerful Frankish leader, Charles Martel),6 but also succeeded in conquering all the neighboring German tribes in north and central Europe, and even (at the invitation of the Pope in Rome) defeated the powerful tribe of Lombards in Italy. Thus on Christmas day in the year 800, the pope, in recognition of this great military achievement, crowned Charlemagne as emperor, a title not used since the fall of Rome some 350 years earlier. With this achievement, Charlemagne not only broke the power of the individual German tribes – at least on the European continent7 – but had the Church recognize officially his right to rule much of Europe as his personal property or fief.

The Principle of Subinfeudation

However, this fief (Latin: feudom) was a vast piece of territory to rule. Unlike the former Roman Empire, Charlemagne had no well-developed bureaucracy of trained government officials placed around his Empire to rule on his behalf. So, Charlemagne instituted the policy of awarding large sections (fiefdoms or feudatories) of his personal empire to various barons (princes and dukes, etc.) to govern on his behalf, that is, in his name. Charlemagne still held the full title to the land since all of this was now considered his (like private property), his to lease out to others as he saw fit. His tenants or vassals (the princes and barons) in turn owed Charlemagne loyal service in maintaining the peace of the land and providing him troops in case of war. They did not pay taxes because no one, not even the barons, had much by way of money. The obligation of personal service to Charlemagne as their lord was what was required of them. But even for the barons, the territory they were responsible for was still too big for any one person to govern. So they in turn sub-leased portions of their own lease to lesser land-lords (marquesses and counts, etc.), under the same type of obligation that they owed the emperor: land tenure (land-holding, not land-owning) for various services in return. Thus, although the barons were vassals to the emperor, they were themselves lords to their own set of vassals lower on the feudal scale. Finally the system reached down to the masses of peasant farmers and their families (actually about 95 percent of the population!), who were allotted land in return for labor service (working their lord's fields and maintaining his flocks) and the requirement that a portion of their harvest or produce be turned over to the local lord and his court of knights and ladies. The peasants themselves owned almost nothing (except maybe their most humble clothing), usually not even the houses they lived in. No money was involved, just the right of a certain amount of landholding and the obligation of certain services in return. This in short was the feudal system In theory the emperor was free to extend or take back land rights to whomever he chose, for however long he chose to do so. But over time it became a lot easier for a lord to allow a vassal to pass his land rights on to his sons (or his eldest son only – under the rule of primogeniture that was widely practiced in Europe). After a number of generations, a family would begin to consider this land theirs to have and to hold as they chose. This created difficulties between the lords (such as the European kings) and their vassals (their barons) that were never fully worked out satisfactorily. Some clever dukes were able (through conquest, although most often through marriage) to accumulate sections of land here and there, sometimes at great distances, even under different lords. The Dukes of Normandy, for instance, ended up holding more land of their own than the French kings they were supposedly under (but the Dukes of Normandy were also kings – in England – by their own right). It could get to be very confusing. But the principle always remained the same: land, land, land. Social status depended entirely on the amount of land a baron was able to hold. And land tended to stay within the realm of one's family. And thus inheritance (not hard work or industrial cleverness) ruled the status system. A person was born into his or her status, and was carefully married off in accordance with the dictates of that same status system. What possibilities life might bring a person were determined entirely by that person's birth. And so it was. And so long it was that few ever thought that things could be otherwise. 6Charles

Martel (the "Hammer") had made his own great place in history by being

able to stop the spread of Islam into Europe by defeating Muslim forces

at the Battle of Tours (732) in central France. He went on to

establish the Carolingian dynasty ruling France, which Charlemagne was

soon to head up. 7The

Saxons and Celts of the British Isles excepted, as they continued to

lay outside Charlemagne's conquered territory. Likewise, most of

Spain also fell outside Charlemagne’s realm because it remained under

Arab-Berber Muslim control, and would do so in part for the next 700

years.

|

Equestrian bronze statuette

of Charlemagne (900s)

From the Treasury of the

Metz Cathedral (France)

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

|

Viking blood added to the mixture.

But about the time Charlemagne was bringing Western Europe under this

feudal system, attacks were happening along the edges of his vast

Empire – and across the way even in the British Isles. Northmen

(Normans) or Vikings coming from the Scandinavian North were beginning

to conduct horrible raids on Christian Western Europe – stopping cold

the cultural advance that had almost got up and running with

Charlemagne's social-political revolution. These Viking raids

effectively plunged Christian Europe back into the Dark Ages. However, around the

start of the second Christian millennium (ca. 1000 AD) the barbaric

attacks of the Vikings or Normans slowed up considerably, giving Europe

something of a degree of peace, the first in a long time. Part of

this was due to the settling of the Normans within the communities they

had once raided ruthlessly – the Vikings or Normans adopting both the

local languages and the Christian religion of the people they had

overrun – now becoming as dukes or even kings, protectors of those same

communities – such as French Normandy, the English Danelaw, eventually

England itself (1066), and even places as distant from the North as the

Mediterranean island of Sicily. And in 1095 this

energy would be called on by the Christian Pope to rescue the Holy

Lands from the Muslim Turkish "infidel" who had made Christian

pilgrimage to the Holy sites of the East very difficult, if not even

impossible. The Normans – but also the Germanic kings and

noblemen (as well as multitudes of commoners) – boldly answered the

call to go crusading ("to take up the cross") in the Holy Lands of the

Mediterranean East. The Crusades which

followed over the next two centuries (1100s and 1200s) in turn inspired

two major developments in Christian culture or civilization at the

time. First, it involved the outpouring of a renewed religious

spirit eager to spread the Christian faith to the Muslim lands of the

East. This spirit could be found high and low in Christian

society – although the European feudal nobility of kings and princes

quickly took the lead in the enterprise. But secondly, the

Crusades brought the rather materially primitive Europeans into direct

contact with the East's fabulous wealth, such wealth as Western Europe

had not seen since the fall of Rome many centuries earlier. Not

surprisingly, the Crusaders themselves wanted to participate in that

world of wealth. Some of the Crusader noblemen even settled

themselves amidst the wealth of Islam, establishing Norman kingdoms in

the recently conquered lands of the Middle East – sort of "going

native" – not exactly abandoning their Christian faith, but wanting

very much to combine their Christian world with this higher level of

Muslim material wealth. But this new hunger for material wealth

would include also those crusaders who returned to their kingdoms and

principalities in Europe after having fulfilled their pledges to

crusade for Christ in the East. The Franciscans and Dominicans.

In the early 1200s a spiritual "awakening" was to come to a young, very

wealthy and very brash Francis of Assisi, through both a series of

personal hardships and a mystical call to give his life over to serving

the poor, as Christ himself exemplified. In fairly short order a

much-transformed Francis attracted a large number of other young

Italians to such service, forming something of a monastic community,

which the Pope then forced him to bring under Roman or papal

supervision (lest he be declared a heretic). Out of this the huge

Franciscan movement developed, one that would eventually take

multitudes of Franciscan monks to all corners of the world, and one

that finds Franciscans even today serving the poor both in urban

ghettos and rural villages everywhere. At about the same

time (also the early 1200s) another individual, the Spanish priest,

Dominic de Guzman, began to train Christian teachers in order to

rebuild proper faith in the Church and its Christian ministry.

Here too his new monastic movement (with considerable papal support)

spread rapidly around Europe, as vast numbers of Dominican monks or

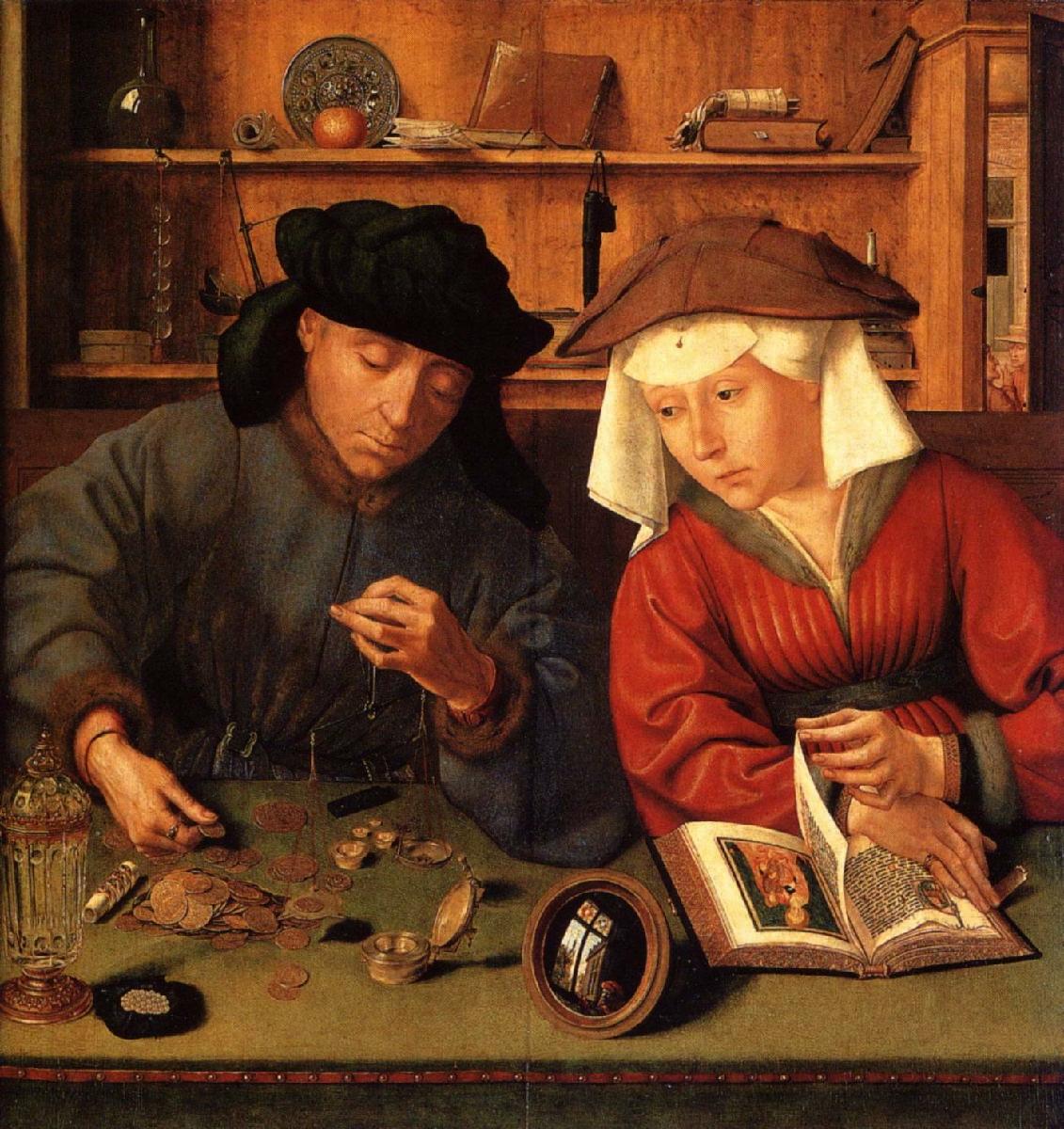

"Friars" were sent out to teach and enforce Christian orthodoxy. The rise of urban Europe. Contact with the Muslim East (the

crusades of the 1100s and 1200s) also birthed a new system of wealth

founded not on landholding but on the ability to accumulate mobile

wealth (goods, money, bank credit, etc.). Such wealth, like the feudal

system, could be acquired and passed on to future generations of the

family. But mostly it came as a challenge to each generation to grow

its own wealth in industry and trade – something that feudal

landholding could not do. Land, of course, could be exchanged with, or

seized from, another. But the overall supply of land itself could not

be increased any. However, the money economy had no limits placed on

its ability to expand.

Feudal lords naturally looked down on the

lower-status industrial-financial achievers as mere wannabees, not

really worthy of serious social consideration. In short, feudal lords

were snobs. But monied wealth had its own way of having an impact, even

socially and politically. Kings, who always had troubles with their

much-too-independent-minded barons, found that working with these

industrial entrepreneurs from the rising urban middle class (neither

barons, nor peasants but socially in the "middle") worked to their

great advantage.

Kings were willing to license

industrial groups (grant them charters as corporations or companies) in

return for a tax portion of their monetary earnings or profits, taxes

which allowed kings to hire their own soldiers and purchase their own

arms, rather than be forced to rely on the not very dependable military

services of their barons or lesser lords. Also, with the development of

overseas interests on the part of kings and princes, a navy of fighting

ships had to be constructed at considerable financial cost, something

that only the moneyed classes could fund – but also derive considerable

benefit from as much-needed protection in their trading – something

also that the landed aristocrats of the countryside had nothing to

contribute to or gain from.

Taking advantage of this newly awakened consumer or materialist spirit brought

on by the crusades were a number of port-cities located strategically

along the sea routes that made for easy access to the wealth of the

East. Prominent in this regard within the key Mediterranean

region were a number of city-states of Italy, not at all feudal domains

but instead types of urban republics – the most important being Venice

(which actually went on to develop a vast commercial empire linking

Europe and the East) – but including importantly also Genoa (another

shipping center) and Florence (a banking center situated in the center

of the flow of moneyed wealth East and West). But coastal

cities of the Atlantic – such as Portugal's Lisbon, Flanders' Antwerp,

Bruges, and Ghent and England's London (not on the coast but accessible

to the high seas by way of the Thames River) – and the cities of the

Hansa League of northern Germany, such as Lübeck, Hamburg and Danzig

and the Rhine region such as Cologne also got involved – and also grew

quite wealthy from this new East-West trade.

The rise of Portugal and

Spain. Meanwhile, the feudal dynasties themselves did not want to be left out of this

scramble for wealth and power that was clearly benefiting these rising

city-states of Italy, Flanders and other coastal regions. Thus the

Portuguese kings of the House of Aviz in the mid and later 1400s sent

explorers from coastal Lisbon to look for a direct passage to the

wealth of the East by going around Africa – thereby avoiding the

expensive Italian and Muslim middlemen of the cross-Mediterranean

route.8 Not to be outdone by the

Portuguese, the Spanish monarchy of Ferdinand and Isabella at the end

of the 1400s commissioned the Genoese sailor Christopher Columbus to

locate a supposedly more direct route to the wealth of Asia by heading

west directly across the Atlantic – presuming that Asia was only a

short distance to the West. What a surprise Columbus had when he ran

into islands just offshore of a vast landmass whose existence Europeans

were completely unaware of. This discovery would ultimately inspire

Spanish adventurers to head to this new land (given the name "America")

– when rumors of vast quantities of gold were soon verified with the

discovery – and plunder – of both Mexico and Peru (early 1500s). At this point the Spanish

Habsburg dynasty (actually originally Dutch) loomed far above all other

European dynasties (the Valois of France and the Tudors of England, for

example) in wealth and thus also power. Habsburg Spain would in fact

continue to dominate Europe totally during the 1500s – thanks to this

huge flow to Spain of plundered American wealth in gold and silver. England and France. For England and France, the Hundred Years' War

raging between the mid-1300s to the mid-1400s also served to strengthen

the hands of the French and English kings, by simply bleeding off the

feudal aristocracy in endless slaughter. In France those wars left the

feudal lords so devastated that in 1439 the king was able to put

literally the entire military establishment and an entire national tax

program into his own hands. In England the chaos continued an

additional three decades (until 1485) in an ongoing dynastic struggle

(the War of the Roses) between the two royal houses of York (White

Rose) and Lancaster (Red Rose) serving to weaken even further the

remnants of the old feudal order. In that last year, a distant

Lancastrian cousin of the House of Tudor was able to grab power, marry

a York princess, and finally, as King Henry VII, bring an exhausted

England under his firm grip. At Henry's death in 1509 his son Henry

VIII took the throne and continued to strengthen the monarchy, this

time at the cost of the medieval Church – whose lands he confiscated in

order to award the Church's vast wealth to his own political

supporters. Thus in the early-to-mid-1500s, royal absolutism also came

to England.

8Actually, before even reaching the lands of the East (India principally), the Portuguese had become quite wealthy in acquiring African gold and slaves.

|

|

|

Renaissance Europe. By the early 1500s, something else was stirring in the hearts

of the Europeans – some of them anyway. The personal empowerment in

wealth and the opportunity to explore life more deeply during the

European Renaissance served to challenge inquiring minds to examine

more closely the way European life itself was structured. Indeed, all of this new flow of wealth

and power was producing a vast cultural awakening, later termed the "Renaissance"

(French for "rebirth"). God and Christ were becoming upstaged in popular

interest by simply the life of man himself, and his new-found ability

to bring his world seemingly under human mastery. Thus "Humanism"

increasingly became the cultural motif of Renaissance Europe. A classic example of such

Humanism was found in the works of the political analyst, Niccolò

Machiavelli. In his early 1500s study, The Prince, Machiavelli

insightfully described the way for a dictator to bring unity to a

conflicted society, through everything from brute force to simple

political deception. Humanists would later denounce Machiavelli for

his less than elegant depiction of the human spirit. But they would

also find it impossible to prove him wrong. In any case, none of this

had anything to do with traditional Christianity and its role in

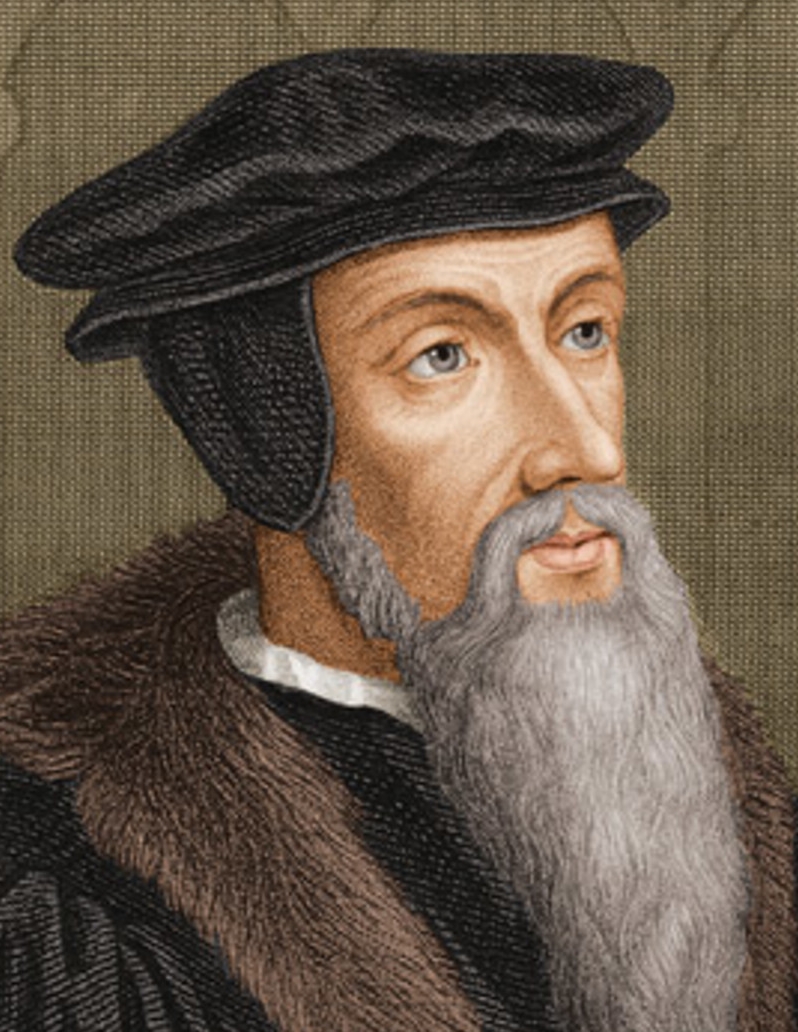

European society. Tragically, the Church had itself become caught up in the world of constant, sometimes even brutal, politics – and very little spirituality. A Christian "Awakening"

The

Christian social identity of Europeans had long been the foremost of

all the particular identities that a person might hold, back in

pre-modern Europe – even more important than English, or French, or

Spanish. National identities and national politics, especially on the

European continent, were only in their very early stages of

development. The people who governed European society married across

national or linguistic lines and ruled lands whose inhabitants spoke a

variety of languages. Most Latin-speaking European kings and princes

viewed themselves not as national defenders but simply as rulers of

multi-ethnic lands, personally called to keep the peace and preserve

the Christian faith in their assigned lands, wherever those lands might

be.

It is important to note that of all their

responsibilities, the greatest was still considered their divine call

as defenders of the faith. But it was also in this area of defending

the faith that considerable tension had been brewing in Europe by the

early 1500s. Many Christians felt that the Church had long departed

from its original spiritual mission and was more interested in securing

wealth and power for itself than in guiding and guarding the souls of