|

|

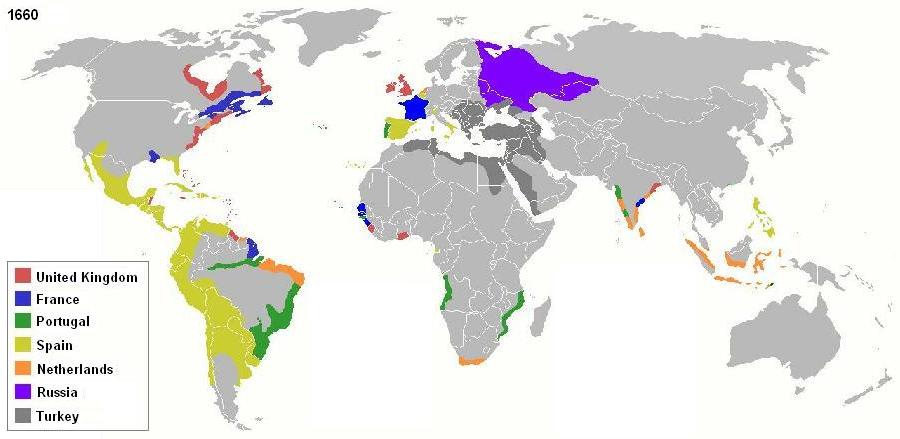

The Spanish first set the agenda for American exploration and settlement The Spanish first set the agenda for American exploration and settlement The French get involved The French get involved The Dutch get in on the act The Dutch get in on the act England stirs under the Spanish challenge England stirs under the Spanish challengeThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 39-42. |

|

| At the time (the 1500s), when these two Catholic and Protestant

cultures were first confronting each other, the leading power of Europe

was unquestionably fervently-Catholic Spain, under the rule of the

Habsburg family. This was due in part to the toughness of the Habsburg

kings, Charles and his son Philip, but also in part (in great part

actually) to the flow of gold into Spain resulting from the Spanish

plundering of American Indian societies, notably in Mexico and Peru. When, on behalf of the newly combined Spanish monarchy of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, Columbus had discovered America in 1492, he had introduced Europe (but in particular Spain) to a vast land soon revealed to be of considerable wealth, including very importantly gold. The Spanish were of course the first to benefit from this discovery, and they benefitted royally. The Spanish plunder in gold and silver taken from Mexico and Peru made Habsburg Spain the richest and most powerful society in all of Europe during the 1500s. Spain secured this huge wealth by sending young and aspiring (that is, lesser) noblemen to America to secure the bulk of this wealth for their king – and personal wealth and noble title for themselves in the process. These young men fulfilled their aristocratic ambitions not only by pure plunder, but by taking over the indigenous Indian population and working them in the mines and on the land. This slave-like labor provided an on-going source of wealth for these new Spanish lords. A feudal-like political system thus settled over Spanish America – much like the system back in Europe where peasants and serfs worked almost endlessly for their aristocratic lords or masters. Thus it was that the opening up of America extended the Spanish feudal system to that continent, a feudal system offering wealth and dignity to aspiring lesser nobility, or to nobility who had simply fallen on hard times economically, or to those simply seeking to escape their positions among the lower social orders of feudal Spain, hoping to rise to the status of noblemen from newly acquired American wealth in land – and servants working that land for them. Spanish kings however were not very comfortable with the ambitions of these young conquistadores (conquerors), who were merciless exploiters of the labors of the American Indians that had the misfortune of falling into the hands of these adventurers. The Spanish kings considered the Indians their personal subjects, much like the Spanish peasants who worked the aristocrats' lands back in Europe. Also, the Spanish kings felt something of a moral responsibility for extending the reach of the Christian faith to their Indian subjects. So, the kings sent Dominican and Franciscan monks to America to accompany or follow-up the conquistadores, to convert the Indians – and then to protect them from the cruel greed of those Spanish conquistadores. Thus to the mix of a rising Spanish feudal system in America in which Spanish noblemen ruled the surrounding land and its inhabitants from their feudal manors or haciendas, the kings added the political oversight of their colonies through the scattered mission stations of the Spanish Catholic priests. These feudal lords and priests were called on to help keep the American social order under the firm control of the political authorities back in Spain.

Meanwhile other ambitious Europeans looked with

envy on the Spanish success in America. But at the time the Spanish

navy so completely dominated the water passages from Europe to America

that it was very perilous for anyone else to attempt to duplicate what

the Spanish were doing in America. The Spanish would simply not allow

the intrusion of European outsiders into their American lands. But the

rewards were too great for other Europeans not to try to challenge the

Spanish monopoly. |

Hernán Cortés

Francisco Pizarro

Spanish conqueror of

Mexico

Spanish conqueror

of

Peru

The Spanish establishing themselves at St. Augustine, Florida – 1565

|

as he stands at the mouth of the river

The Historic New Orleans

Collection

| Spain

had not appeared as interested in North America as it did in Central

and South America. Therefore, North America seemed to offer the best

possibilities for others to get in on the act. By the beginning of the

1600s it seemed that the time was right – particularly after the

Spanish army and navy had experienced a string of disastrous setbacks

trying to keep both their Protestant Dutch subjects from breaking away

from Habsburg Catholic Spanish authority and the English privateers

(actually merely pirates officially authorized by English Queen

Elizabeth) from harassing the Spanish fleets bringing gold from

America.

The French thus sent explorers and traders to the Maritime Islands of eastern Canada, and then beyond up the St. Lawrence River – to take advantage of the great wealth in animal furs of the more northerly region of the Americas. But they also sent Jesuit priests to Canada to bring Indian souls to the French (Catholic) Church.1 But the chill of the Canadian North proved to be not greatly inviting to French settlers, and the French imperial venture in Canada did not take on great importance in the larger French political scheme of things. 1Eventually

both French Jesuits and explorers reached even deeper into the new

continent, doing extensive exploration (and some settlement) along the

massive Mississippi River, north to south. |

|

| Since

the Spanish quest was for aristocratic status, not success at the game

of commerce and trade, very little of this Spanish plunder got devoted

to the building up of Spanish industry and commerce. Almost all of it

went to the purchase of land, and aristocratic title that went with the

land.

However, the Dutch, who were part of the Spanish kingdom2 (even though way north of the Spanish heartland) and of a strong Protestant- Calvinist disposition, were a different breed. The land of the Dutch was small in land size, highly urbanized along the long coastline, and divided into two distinct regions: Flanders, the region just to the north of France (and directly across the Channel from England) whose coastal cities achieved vast wealth early in the Renaissance period; and, north of Flanders, Holland, much of that region wrested from the North Sea by the Dutch through a laborious process of building dikes to hold back the sea in order to bring up more tillable land, and then draining additional seawater seepage into that land by way of windmills. These Dutch provinces were dotted with cities engaged in manufacture, banking, shipping, and trade. Ultimately, much of the Spanish wealth brought back from America by the Spanish conquistadores tended to end up in the hands of the very industrious and commercially clever Dutch. Nonetheless, Habsburg Spain, as long as the gold held out, appeared wealthy and powerful, and dominated European life. But when that gold ran out (as it was destined to do) aristocratic Spain began to slip rapidly in power. But the Dutch, who had learned how to invest that gold in projects that multiplied their wealth, turned from this small outpost of the Spanish kingdom into a major European power. Little by little (late 1500s) the Dutch began to move toward independence, precipitating a terrible war initiated by Spain in an attempt to force the Dutch back into submission. The Spanish effort succeeded in the Flemish south (ruining the Flemish cities in the process) – but failed to reach that same goal in the Holland north. All this did was to steel the will of the Holland or Netherlander Dutch – and further drain Spain of its wealth (early 1600s). In the meantime, the Netherlander Dutch had begun their own exploration of the lands to the West in America. They set up a merchant corporation to bring back the wealth of the central shores of North America (a region they called New Netherland), and hopefully to find a passage through America to their valuable commercial holdings in Asia (the Spice Islands of the East Indies which the Dutch had seized from the Portuguese), by way of the Hudson River, along which they established a number of Dutch settlements. 2Spanish

King Charles I was actually Dutch rather than Spanish by birth – born

in Ghent, in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking northern portion of modern

Belgium. |

|

| At

first England's main ambition across the Atlantic seemed to be merely

raiding the gold-laden Spanish galleons shipping their Indian plunder

back from America to Spain. Under Queen Elizabeth, English privateers

were even treated as noblemen: Sir Francis Drake, for instance,

excelled at this game of plunder.

Of course the Spanish tired quickly of this English game and in 1588 sent a massive fleet to crush the English navy, and also force the rather Reform-minded or Protestant English back into the true Mother or Roman Catholic Church. But this mighty Spanish Armada ended up itself crushed by foul winds and clever English seamanship. This marked the beginning of the rise of England as a major naval power, and the decline of Spain as the dominant European power. But it would be a while before the English would themselves get deeply involved in the process of bringing American lands into the English realm. |