|

|

Maryland – the proprietary Catholic colony of Lord Baltimore Maryland – the proprietary Catholic colony of Lord Baltimore  The English Civil War and "Restoration" (1642-1660) The English Civil War and "Restoration" (1642-1660) The Carolina colony The Carolina colony New Netherland – and its capital at New Amsterdam New Netherland – and its capital at New Amsterdam  The English take over from the Dutch and set up New York and New Jersey The English take over from the Dutch and set up New York and New Jersey Pennsylvania and Delaware Pennsylvania and Delaware The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 74-89. |

|

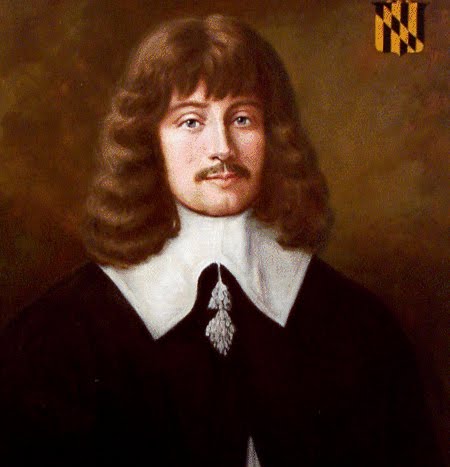

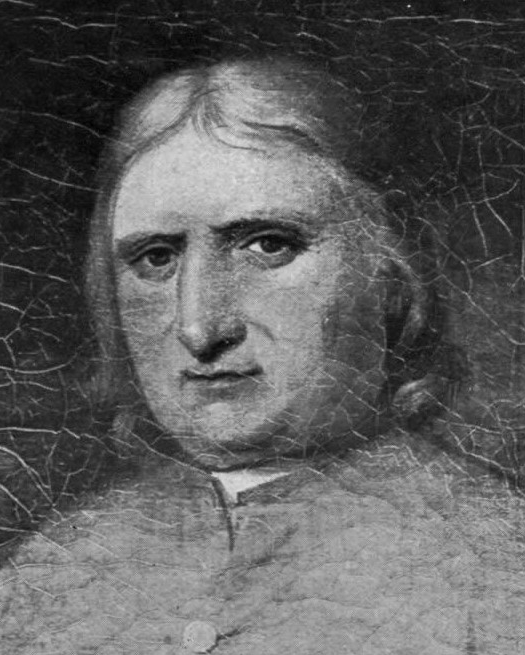

(right)

Leonard Calvert

- brother of Cecil and 1st Governor of Maryland (1634-1647)

Maryland

Archives Online

|

Just as New England was settled primarily for religious reasons, so was

Maryland – except that it was established not for Puritans escaping

persecution, but for Roman Catholics escaping persecution in a heavily

Protestant England. George Calvert (Lord Baltimore), a recent English

convert to Catholicism, saw a double opportunity in securing land in

America – both as a way to enrich his family fortunes, and as a

religious refuge for fellow Catholics. In 1629 he petitioned Charles I

for a tract of land in which to establish a settlement along the

Chesapeake Bay just north of Virginia [he had given up on a similar

venture in Newfoundland because it was simply too cold there!] – but

died before a land grant was awarded by the king. His son Cecil then

took over the project, receiving a royal charter in 1632 – despite the

opposition of the Virginians who claimed the same land as part of their

colony.

Lord Cecil Calvert needed thousands of settlers to make the colony pay for itself, so he made settlement available also to English Protestants, who would actually outnumber the Catholics, even from the very beginning. Thus Maryland was always officially a religiously tolerant colony open to settlement by anyone, regardless of religious affiliation (Catholic, Anglican, Puritan, and eventually Quaker). The venture, beginning with only a couple of hundred English settlers in 1634, started off smoothly, with no starving time or trouble with the local Indians. In the area where the Marylanders first laid out a town (St. Mary's) the local Indians befriended them because they themselves were in need of allies against their own Indian enemies. The Indians sold them the land they first settled and also corn to feed the colony. And soon the rich Maryland soil had the Marylanders producing enough food to easily feed the colony. Lord Calvert was quick (1635) to grant his settlers a voice in colonial affairs with an assembly that operated much like the colonial assemblies of Virginia and New England. Nonetheless Maryland could not escape the Catholic-Protestant religious tensions that tore at the mother country England, and in 1655 Maryland experienced its own religious civil war, which temporarily brought a Protestant government to power in the colony. In most respects Maryland differed very little from its neighboring colony next door (Virginia). Tobacco was the main crop, at first worked by indentured laborers – and then over time by slaves. The colony was dominated by an aristocracy, set up early by the Calverts, who gave large land grants to family members and fellow English gentry. This, as in Virginia, created in Maryland a distinct upper class that stood socially far above the common dirt farmers who came to Maryland as indentured workers. |

Maryland

Historical Society

|

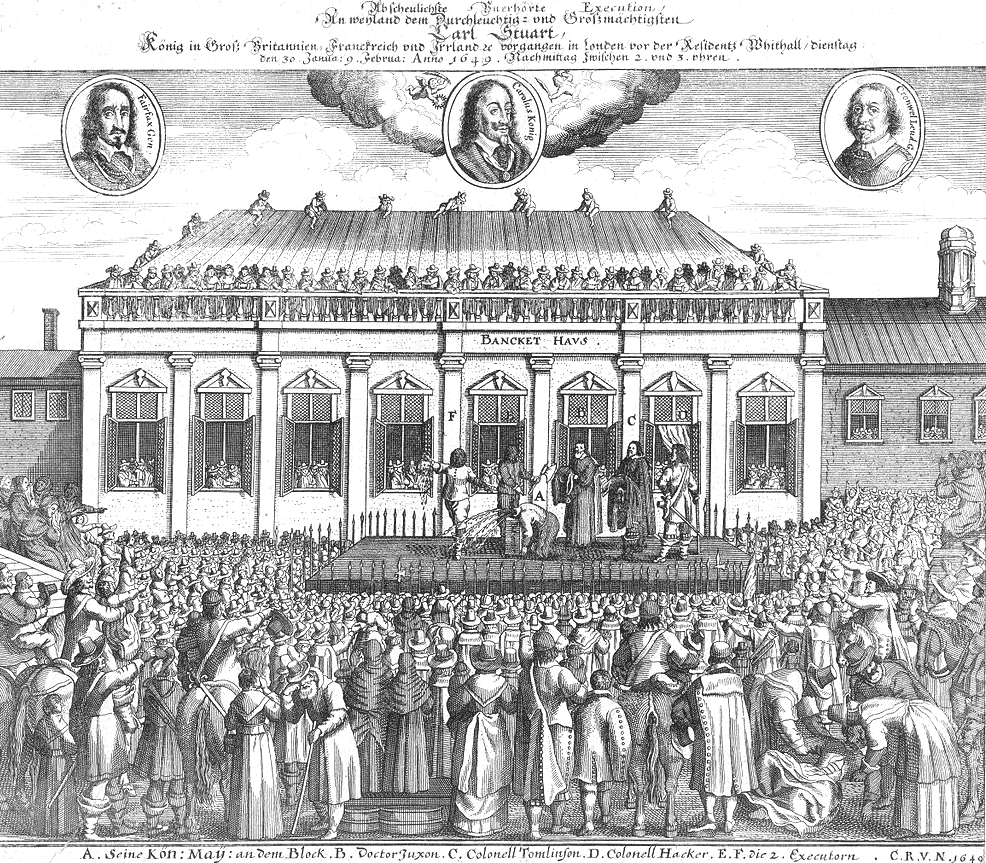

Head of the English Puritan Commonwealth (1649-1659)

National

Portrait Gallery,

London

Cromwell – having captured Charles's personal baggage and correspondence

at the Battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645)

| The

practice of granting American lands to royal supporters would fall out

of use until the "Restoration" to the English throne in 1660 of Charles

I's son Charles II following the end of the English Civil War.

The English Civil War (1642-1649)

Just as the bitter conflict between Protestants and Catholics settled down on the European Continent, it exploded in England. The Puritan-dominated Parliament and the English King Charles I, caught up in inflexible religious differences, squared off against each other, complete with armies of their own (1640s). But the Parliamentary Army (mostly Puritan in character), under the highly disciplined command of Oliver Cromwell, proved to be vastly superior to Charles's Royal Army, and Charles fled to Scotland, only to be arrested and sent back to England (1646). But Charles was not finished, and attempted to induce the Scots to change sides and support him (promising to institute Presbyterianism throughout his realm).1 The Scots agreed, but proved to be unable to defeat Cromwell's Puritan army. Cromwell entered London and authorized a greatly reduced or "Rump" Parliament of Cromwellian supporters to conduct a trial (and conviction) of Charles under the charge of having committed high treason. The Rump Parliament complied, and in January 1649 Charles I was duly convicted and beheaded. Charles's eighteen- year-old son (also Charles) took up the Stuart family cause. But the young Charles II was soon driven into exile in France.

The Puritan Commonwealth (1649-1659)

At this point the Rump Parliament declared that England (but also Scotland and Ireland) had come under the governing authority of a Commonwealth (Anglo-Saxon for "Republic" meaning "belonging to the common people") headed up personally by Cromwell. A few years later Cromwell would even be proclaimed Lord Protector for life, satisfying those who still believed that England needed to fall under some kind of royal rule. And indeed, Cromwell's military-run Commonwealth (similar to Caesar's ancient Imperial Rome) finally brought peace to England, Cromwell ruling the country throughout the 1650s with an iron fist. At the same time he continued the brutal effort to crush Catholic rebellions in Ireland – and to a lesser extent Catholic or pro-Stuart rebellions among the Scottish Highlanders. But the Puritan domination (the era of the Puritan Commonwealth) in England was short-lived. Tragically, this venture in Puritan government in England possessed none of the moral or spiritual qualities that, for instance, Winthrop and others had, a generation earlier, laid out in America with their Puritan Commonwealth. Consequently it failed to win the hearts of the English people. In any case, Cromwell died in 1658 and his son Richard then took over the Commonwealth. But Richard had no political leverage (such as his father possessed with his army) needed to control the factions that vied for power within the Commonwealth. Consequently, the army began to fall into feuding, and Royalist sympathies quickly began to make a comeback in England. Richard was soon driven from power by one of the factions, forcing one of Cromwell's generals, George Monck, who had been governing Scotland, to march on London, put in place a new Parliament, and begin negotiations with the exiled Charles II for the restoration of the monarchy in England, something clearly desired at this point by most of the English.

The Restoration (1660)

Finally in 1660, terms were agreed on with Charles II for his return from the Netherlands in order to retake the throne of England. With him came numerous Royalists to reclaim their former positions of privilege. The king, in his gratitude to his supporters, even granted them rewards beyond mere restoration of what had been lost. In gratitude for their support during his exile and his return to the throne, Charles presented a number of them with full title as proprietors of new colonies in America – on much the same basis as those by which his father had some thirty years earlier granted Maryland to the Calverts as a proprietary colony. 1The distinction between Presbyterians and Puritans was actually very small, and only in terms of organization, not theology, as both were fully Calvinist. Puritans believed in the total independence of each local congregation, especially in the matter of choosing their own pastors. Presbyterians believed in a higher union of their congregations at the regional or presbytery level, each of their congregations sending pastors and elders to represent them regionally at Presbytery. The presbytery would have some say in certifying (or rejecting) the pastoral calls to the pulpit of the local congregations within its district. Likewise, the presbyteries would be united even more widely at the synod level, with the presbyteries likewise sending pastors and elders to represent the presbyteries at that higher level. In short the distinction was one of pure democracy versus representative democracy, a distinction that it seems should not have been worth fighting over! Actually the fight was more one of national spirit (Scottish versus English) than it was one of ecclesiastical organization. |

Cromwell's New Model Army defeats a Scottish army

twice the size of his force at the Battle of Dunbar (September 3, 1650)

General George Monck – Cromwwell's Governor of Scotland –

negotiates the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II in 1660

Charles II – King of England, Scotland and Ireland (1660-1685)

|

| In

1663, Charles II granted to eight English noblemen a huge grant of land

to the south of Virginia, in theory all the way to Spanish Florida. The

land was termed Carolina in honor of his father, Charles I. The eight

proprietors included Virginia governor Berkeley; George Carteret (also

soon to be a New Jersey proprietor); the king's Lord Chancellor, Edward

Hyde, (Earl of Clarendon); and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Anthony

Ashley Cooper (eventually the Earl of Shaftesbury) – the last-mentioned

who would be the main driving force behind the Carolina colony. They

planned to make the colony quite accepting of the widest variety of

religious groupings, Catholic and Jewish as well as Protestant, in

order to make their investment a success.

Actually, English settlements had already been established just to the South of Virginia along what is today the North Carolina coast. Then Berkeley convinced some of the landless of Virginia to move to his new Carolina colony, although there too they settled only in the area (Albemarle Sound) immediately south of the Virginia colony. But further south saw virtually no settlement – until Shaftesbury convinced the partners to be more active in the enterprise.

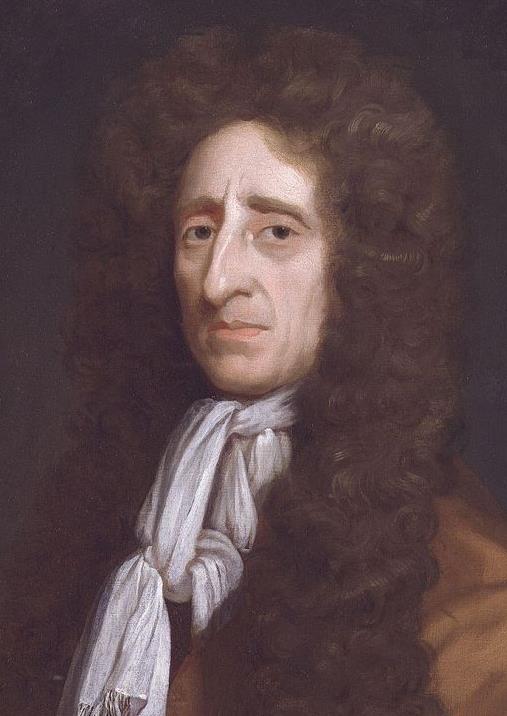

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury

Leading this Carolina venture was an Englishman of exceptional moral integrity – at a time when it could be very dangerous to be a man of such integrity. Cooper was something of a social optimist, yet very much a realist in the way he carefully moved towards his ideals. Although Cooper was nobly born (both mother and father), he lost both parents by the time he was eight and was raised by various trustees named in his father's will, all of them well connected Members of Parliament. At age fifteen, Cooper entered Oxford (Exeter College), studying under a strong Calvinist master, and then the next year switched his energies to the study of law at Lincoln's Inn, where he was influenced greatly by the Puritan perspective on society. At this point Cooper confirmed strongly his dedication to what he understood to be the very highest Christian principles. He was never one who was willing to follow particular doctrines and policies just because they were the political trend of the day, whether during the time of the Royalist ascendancy or the time of the Puritan ascendancy. He learned to work with both parties, but always cautiously. As a youth of only eighteen he was elected Member of Parliament, and at first took a position in support of the king in Charles I's expanding conflict with the growing group of Puritans in Parliament. However when at his own expense he assembled a regiment and participated in a Royalist victory at a battle in 1643, he ended up deeply shocked at how the Royalist commander Prince Maurice ignored the negotiated peace that Cooper had worked out with two Puritan towns, and instead Maurice simply plundered the towns. By 1644, disgusted with the Royalists' behavior – and their increasingly obvious Catholic instincts – Cooper chose to change sides and join with Parliament's anti-Royalist faction. But even then, he showed more the instincts of the (mostly Scottish) Presbyterians than the Puritans in his willingness to find some way to bring peace to the land through compromise with the king. At this point he held back from further political controversy and quietly took up responsibilities as a local sheriff. Then he turned his interests overseas, purchasing property in Barbados in 1646. When the monarchy was overthrown in 1649 and the Puritan Commonwealth took command of English society, Cooper was cautiously returned to larger political responsibilities by Cromwell's Rump Parliament and was soon voted membership into that body. Then Cromwell appointed him to serve on the Council of State, helping to create a new legal structure for England. But Cooper seemed more interested in limiting than in authorizing the rising power of the Cromwellian Protectorate, raising suspicions that he was still a Royalist at heart (not true). Somehow however Cooper was able to wade through the accusations and counter-accusations of both friend and foe to continue to keep his seat in the constantly evolving Parliament. But with Cromwell's death and the inability of Cromwell's son to hold the Commonwealth together, Cooper joined in 1658 with a small group working to bring General Monck and his troops from Scotland to London to restore a degree of order to the crumbling situation. Monck shut down the Rump Parliament, restored the former Long Parliament (itself shut down by the Rump Parliament in 1648), which then subsequently voted for the restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II, before it dissolved itself in 1660. Then Cooper traveled with the delegation sent to The Hague to escort Charles back to England. This put Cooper in good standing with Charles, who would be looking for supporters in assuming his new responsibilities in London. Indeed, upon arrival in London, Cooper was appointed to the king's new Privy Council. At this point Cooper became a key voice for reconciliation, convincing the king and the Cavalier (Royalist) Parliament to ease off on the severity of the Clarendon Code – rather than take revenge on those English who had been involved in the Commonwealth (excepting those who had been part of the execution of Charles I), a very wise voice in getting England to let go of the past and move on to new things. The king was impressed and in 1661 elevated Cooper to the position of Lordship as Baron Ashley. Ashley (as we will now term Cooper) thus left the House of Commons to take a seat in the House of Lords. Soon thereafter the king named Ashley as his Chancellor of the Exchequer – the second most important position in the royal cabinet behind that of the Lord Chancellor (or Prime Minister) held by Edward Hyde, the Earl of Clarendon – with whom Ashley would clash constantly during their years of mutual service to the king in the 1660s.

A Grand Experiment in Social Planning

Meanwhile Ashley had not forgotten his interest in colonial affairs, and joined a group of eight Lords Proprietors (including Clarendon) in developing this huge tract of land south of the Virginia colony that they had been granted by the king in 1663. Ashley proceeded to work on his Carolina territory with John Locke, who at the time was living under Ashley's patronage as both household physician and personal secretary, to devise a major program of enlightened social structuring for the Carolina colony. Eventually (1670) what resulted was the Grand Model. This comprehensive plan included not only the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina but also the designs for the actual settlement of the colony. However, like both Ashley and Locke themselves, the Grand Model was very visionary – too visionary in fact to be of much use as it was drawn up. Locke's design provided for a very orderly division of the land into counties and land parcels assigned to a highly stratified society, from Black slaves and property-less Whites up to the largest landholders, which were the proprietors themselves. Every Carolina inhabitant would receive from none to extensive political rights depending on the amount of property he possessed, Locke (as most of the social philosophers of his time) being convinced that property was the best guarantor of a true sense of social responsibility on the part of a citizen and thus also the amount of social authority that should be entrusted to him.

The Progressivist Urge of the Rising Age of Enlightenment

However, as things turned out for Ashley and Locke, much of the Grand Model had to be reworked according to the hard realities of life in a largely unmanageable, even highly dangerous, American wilderness. Nonetheless this noble effort well-represented the kind of social idealism that was coming into vogue in Western culture at that time. Ashley's and Locke's efforts stood at the heart of a rapidly changing attitude among a rising group of Western social philosophers concerning society and its ways. The old social habits that people had long understood as the unquestionable foundation of all social organization seemingly now needed to give way to a new sense of social organization, one born of careful or rational social planning. In short, the world at that time seemed to need enlightenment, not tradition. Thus political ideals swung slowly toward the understanding that carefully constructed human logic would inevitably produce better ways of organizing life on this planet than had long been the case.2 And the New World offered just the perfect opportunity to put these grand ideas into practice – or so the hope was anyway, one that would never die despite the unwillingness of hard reality to give way to such idealism.

Ashley's Later Years (as the Earl of Shaftesbury)

In 1667 Ashley became part of the team or "Cabal" (Clifford, Arlington, Buckingham, Ashley and Lauderdale!) that governed England until 1674. Meanwhile, in 1672 Ashley was elevated to the position of Earl and received a new title, the Earl of Shaftesbury, and soon thereafter briefly served as the king's Lord Chancellor (1672-1673). Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, had reached the pinnacle of political success in England. But from there it would be a bumpy ride for Shaftesbury, as his political ideals constantly got him in serious trouble (especially his role in founding the Whig party) - culminating in his arrest (1681) and flight from England (1682) and death (1683) because of his participation in the effort to have Charles's brother and heir to the throne, James Duke of York, excluded from this inheritance because of James's strong Catholic sympathies.3

The Carolina Colony Moves Forward

Meanwhile in 1670, some 300 settlers were enlisted from England to settle in the Carolina colony, although only 100 of them survived the Atlantic crossing to actually settle in the new colony along the Ashley River (named after Ashley of course!). But the colony began to grow. Vital in its growth was a special trading relation with the English Caribbean colony of Barbados, where the slave trade was robust (several of the Carolina proprietors themselves were involved in the slave business). Ten years later (1680) Shaftesbury laid out nearby a new town, Charles-Town (Charleston), located where the Cooper River (also named after him) meets the Ashley River. Charleston was soon to become the hub of an extensive trade between Indians and Europeans in furs and pelts – as well as (after 1700) rice farming, which accompanied the rapid growth in the colony's slave population. By the mid-1700s, with the addition of the trade in indigo, Charleston had succeeded in making itself the most prominent city in the American South. In the meantime, because the northern and southern parts of the Carolina colony were so far apart, a sense of a North Carolina and a South Carolina began to develop. Adding to this sense of distinction was the fact that the northern part of the colony was inhabited largely by poor Whites (Presbyterian Scots-Irish brought in from an over-crowded Northern Ireland) living on small self-sustaining independent farms, and the southern part of the colony was a highly stratified society, dominated by aristocratic, High-Church Anglicans – much like Virginia society. Fairly quickly the two areas came to understand that they had little in common, culturally, economically and politically. From 1691 to 1708 they were united under a single governor – but separated again after two years of struggle between the two sections of the colony. In 1729 the proprietors (descendants of the original proprietors) sold most of their rights to the English king, who turned the two Carolinas into two separate Royal colonies: North and South Carolina. 2Tragically, in the abandoning of long-standing tradition, there would be more than just this Ashley-Locke disappointment arising from the effort to find the right utopian formula in the face of life's ever-developing challenges. In fact, failure rather than success – and often very brutal failure at that – would be the normal outcome of such ventures ... over and over again. But there would always be the strong temptation to try again anyway – especially on the part of those who made such armchair social design their main work in life, social philosophers, social critics, journalists, progressive politicians, social studies professors, etc. Despite the miserable historical record of failure of such social ventures, that record would be completely disregarded, so certain were such intellectuals that their newest formula would finally be the one that would bring grand social success (also making them therefore the social geniuses of their day). 3Shaftesbury and his fellow Whigs precipitated the Exclusion Crisis when in 1679 they introduced into Parliament the Exclusion Bill, in the attempt to block James's future accession to the English throne. The Whigs were also demanding that royal authority be placed under the discipline of a written constitution, a shocking idea in the days of royal absolutism. Opposing the Whigs were the Tories, supporters of James and defenders of the doctrine of royal absolutism.

These labels "Whigs" and "Tories" were terms of contempt that one party

assigned to the other: Tories, the name for Irish Catholic bandits,

assigned to those who were opposed to Catholic Exclusion, and Whigs,

the name first for Scottish horse thieves and then later for Scottish

Presbyterian rebels, eventually assigned to those favoring Exclusion! |

Social philosopher John Locke - Shaftesbury's household physician and personal

secretary ... and designer of the 1670 Grand Model for the development of the Carolina

colony. This was a plan "perfect" in every way ... except meeting the actual requirements

of political reality in the Carolina setting.

|

| Another

piece of American territory to be granted by Charles II as a

proprietary colony was New York (formerly New Netherland), seized in

1664 from the Dutch by Charles's navy, under the command of Charles's

brother, James, Duke of York (the future King James II). In fact, it

was to his brother James that Charles granted this important

proprietary colony.

Dutch New Netherland - The Early Years

Greatly problematic for the English with their Southern colonies in Virginia and Maryland and Northern colonies in New England was the Dutch settlement of New Netherland, wedged into the Mid-Atlantic coast between these English colonies. In 1609 the Dutch had commissioned the English sea captain Henry Hudson to explore the area in an effort to find a river passage across America (no one at the time knew how broad the North American continent happened to be) as an alternate path leading to their valuable commercial holdings in Asia, the former Portuguese Spice Islands of the East Indies. Hudson's discoveries included the large bay at Manhattan, and the wide North River (eventually named after him) which fed that bay – but also the realization that this river was not the fabled water route to the Far East. However, it flowed through very fertile lands which would be quite suitable for Dutch settlement and for a staging ground for trade (in furs, mostly) with the Indians. Indeed, Hudson's voyage was soon followed up by further Dutch exploration of the region – and the building of a Dutch fort in 1614 well up the North (Hudson) River at today's Albany. To further secure their claim to various parts of the New World, in 1621 they set up the Dutch West India Company, which in 1624 planted its first Dutch settlements also at today's Albany and on Governor's Island in today's New York City. Then in 1625 they brought in a small number of additional colonists to establish settlements at what they hoped to be their northern border at Fresh River (today's Connecticut River) and at their southern border at the South River (today's Delaware River). And in 1626 the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the North River was selected as the capital of the entire Dutch province. There they built Nieuw Amsterdam. But the Dutch colony was not a cohesive venture like the English colonies. Unlike New England, Dutch society did not include any particular group seeking to escape the Dutch homeland, the French-speaking Walloons under the new Spanish Catholic domination (in Southern Belgium) being the exception. In fact, recruiting Dutch for New Netherland proved difficult as individuals were needed for the much more profitable East Indies operation, or just defense at home against the Spanish. Thus they recruited widely across the other European cultures in order to find settlers for their American venture. Also, Dutch dominies or pastors sent to the colony were few in number, thus keeping the religious character of the colony very loose. And to make matters even more bizarre, some of the Dutch governors sent by the company to oversee the colony were not of the best caliber, such as Willem Kieft, who needlessly stirred formerly friendly Indians to violent revolt during the 1640s. Furthermore, it would not be until the 1650s that the Dutch could undertake serious Dutch settlement in their New Netherland colony. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which finally ended the very brutal Thirty Years' War, included official Spanish Habsburg recognition of Dutch independence and thus ultimately peace, finally giving the Dutch the chance to move forward in developing their colonial holdings in America. Nonetheless, the Dutch had much difficulty securing political and cultural dominion in the area. The Company made the awards of huge land grants to patroons (essentially land barons) who pledged to settle at least 50 families on their land. This worked (somewhat) along the Hudson River to give it a cultural quality that would last for generations. But otherwise the Dutch colony, in which Dutch was the official or governmental language, remained a wide cultural mix of Dutch, French (Huguenot), German, Swedish, Portuguese – as well as African slaves and allied or dependent Indian tribes – living throughout the colony. It was also more broadly tolerant religious-wise, permitting Calvinists, Baptists, Catholics, Quakers, and even a large number of Jews to practice their religion freely, even though the Dutch Reformed (Calvinist) faith was the official religion of the colony. The new governor brought to the colony in 1647, Peter Stuyvesant, tried to clamp down on the unbridled ways of the colony, attempting new taxes and a stricter religious conformity to Dutch Calvinism – something that simply was not going to work with the very diverse population of the colony, or with the authorities back in Amsterdam who ordered him to back down and keep the doors open to all newcomers (now including a large number of Jews). But for Lutherans, the matter was quite different, for the Amsterdam authorities authorized Stuyvesant to come down hard in restricting the practice of Lutheranism! Since the very origins of the Protestant Reformation there had been something of a rivalry between the Lutheran and the Reformed or Calvinist branches, despite efforts of some of the leaders of these two Protestant groups to bring them to greater cooperation. But the theological quibble over the dynamics of the Holy Communion and the question of church organization always seemed to get in the way of such cooperation.

New Sweden - As Part of the New Netherland

Sweden was also a rising European power in the early 1600s – and joined the European effort to lay claim to American land by settling some of their own people there. In 1637 the New Sweden company (made up principally of Lutheran Swedes, Dutch and Germans) established a settlement named Fort Christina (today's Wilmington) along the upper Delaware Bay. The Dutch had also laid claim to this area, but were not able to enforce that claim until 1655, when Stuyvesant sent a small force to the Swedish settlement and, without firing a shot, forcibly incorporated it into the Dutch New Netherland colony. |

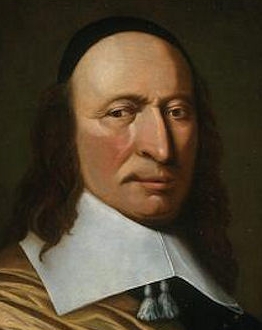

British Museum, London

Peter Stuyvesant – by Hendrick Couturier c. 1660

The Dutch citizens of New Amsterdam pleading with Stuyvesant

to simply surrender to the English

|

|

James's Proprietorship of New York

Back in Europe, the Dutch and English had been locked in a bitter commercial (or just simply nationalistic) rivalry that finally led them to the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the mid-1600s. Their respective colonies in America would certainly be drawn into these wars. King Charles II had wanted to close the coastal gap between his New England and Virginia colonies – and the Dutch province stood in the way. Thus in 1664 Charles dispatched his brother, James, Duke of York, to supervise a naval fleet which would simply take over forcefully the Dutch colony of New Netherland. The Dutch West Indies Company had made no particular military preparations for such an event. In fact, this had been a major grievance of the Dutch settlers. This lack of military preparation by the Company's governors had made the settlers very vulnerable to Indian attacks. Thus they were greatly disenchanted with the Dutch authorities at the time of the English grab of the colony, even seeing English authority as possibly preferable to the authority (not) offered by the Dutch West Indies Company. With no military and with little popular support, Stuyvesant was forced to strike a deal with the English: the English promised the Dutch no expropriation of personal Dutch property and also the protection of a number of cultural and religious freedoms if the Dutch simply turned authority of the colony over to the English. And so in 1664 this huge Province became English territory - for a few years anyway. As a reward for his service to his brother, James was granted title of Proprietor over the Dutch Province, which was renamed the Colony of New York, in honor of James as the Duke of York (he was also at this time given territory to the north of New England, which constitutes today's State of Maine). The Dutch and English commercial rivalry meanwhile continued unabated and soon had both countries involved in yet another war in 1665-1667 (the Second Anglo-Dutch War). At the war's end in 1667, as part of the peace agreement, the victorious Dutch did not attempt to retake the colony but instead reconfirmed the English claim to it, receiving on their part recognition of ownership of Suriname (on the northern coast of South America), which at that time was considered vastly more valuable as a colony because of its sugar plantations! Then came even another Anglo-Dutch War (the Third) in 1673, and the Dutch retook the New Netherland Province. But the war overall was a disaster for the hard-pressed Dutch (also under attack by the French King Louis XIV) and the Dutch were forced at war's end in 1674 to return the Province of New Netherland to the English. At this point James's colony would remain permanently "New York." James never visited his colony but ruled it through appointed agents of his own: governors, councils, and personal agents. He at first did not provide for a popularly elected assembly – remembering the English Parliament during the recent past as being no more than a source of constant opposition to royal rule. He had no desire to offer an opportunity for opposition to his rule to arise in his own colony. However, in 1683 the New Yorkers finally got a colonial assembly and a constitution. However, two years later, when James became the king of England, he canceled this by turning his proprietary colony into a royal colony, making him now more completely the ruler of his New York!

New Jersey

Not all of New Netherland had been converted into James's personal proprietorship of New York. James in turn in 1665 awarded part of New Netherland to his own personal supporters as East Jersey and West Jersey. To Sir George Carteret he assigned the more populous section of East Jersey in settlement of personal debts he owed Carteret. To Lord John Berkeley (brother of the Virginia governor William Berkeley) he sold the section termed West Jersey. Carteret and Berkeley worked together to govern and develop the colony as New Jersey, appointing Carteret's cousin as the first governor of their colony. The two proprietors also issued jointly (1665) the Concession and Agreement document granting full religious freedom in their colony – in order to attract as many settlers as possible. But the venture proved to be not terribly profitable, as settlers tended to refuse to pay their quitrent to the proprietors, claiming that they had received title from the governor of New York. Tensions grew between New Jersey and New York. Ultimately (1674) Berkeley sold his share to a group of Quaker leaders (which included William Penn) – who purchased West Jersey in order to bring in Quaker settlers. In 1688 East Jersey was purchased by another group of Quakers. Although both colonies were in theory Quaker colonies (actually Quakers were by no means numerically dominant in this diverse religious setting), effectively East and West Jersey were now two separate colonies. However in 1702, failing finances forced both colonies to lose their title as proprietorships and become united as a single royal colony (again New Jersey) under the direct authority of Queen Anne of England. |

Battle of Texel (August 21, 1673) during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674)

New Amsterdam ... becoming New York – 1679

New

York Historical Society

|

George Fox – founder of the Quakers in England (mid-1600s)

|

George Fox and the Quakers

The story of Pennsylvania begins with the founding of the Quakers (members of the Religious Society of Friends) in England in the mid-1600s. An English shoemaker and shepherd, George Fox, began to spread a new interpretation of Christianity which caught on quickly in England – and which disturbed greatly the more established Anglican and Puritan Christians. Fox did not believe in original sin (thus diminishing the importance of Christ's death on the cross for the atonement of such sin) – and instead put forward a more Humanist idea that everyone could be saved by simply allowing the Inner Light of God within each person to serve as his or her soul's guide along the path to righteousness. This was a private experience – and required no assistance from a professional member of the clergy (who had no role to play in Fox's religious movement). At first persecuted and arrested, he developed a friendship with Cromwell which briefly brought an end to the persecution – until Cromwell's death in 1658. With the Royalist Restoration in 1660, persecution of the Quakers resumed. The movement initially spread quickly to the New England colonies where it found a grudging permission from Roger Williams to base itself in Rhode Island. Eventually nearly half the settlers there would be Quakers (mostly the other half Baptists).4 But Massachusetts and Connecticut banned the new movement, convinced that its very character was so far afield of what they understood to be Christian orthodoxy that its mere presence undermined greatly the social order of New England, especially when some of its louder adherents returned to those colonies after having been expelled repeatedly for their efforts to convert their people to Quaker ways. Finally, four of the leaders were even hanged5 (1659, 1660 and 1661), before early in his reign, King Charles II decreed an end to such treatment of the Quakers. This was subsequently reinforced in 1689 by the British Parliament's Toleration Act. 4The Baptists were a breakaway group within the Calvinism that was so strong among the English reformers. The critical issue separating the Baptists from the others was the matter of infant baptism, which the Baptists rejected, claiming that only fully believing adults were to be baptized (also by full immersion rather than just the sprinkling of baptismal waters, which was practiced in infant baptism). Calvinists claimed that by making baptism an adult achievement they were following the detested salvation-by-works policy. But the Baptists protested that adult baptism was simply a matter of the Holy Spirit moving on a fully cognizant adult, a matter of Divine grace and not human works. Neither group was able to find a common theological meeting point. And thus the Baptists became a separate Protestant denomination. 5This

included Mary Dyer, Anne Hutchinson's former close companion, who had

become a Quaker and who was expelled from the Massachusetts colony four

times, the last under the threat of death if she were to return. She

did return however, and after some efforts to get her to back down she

was finally hung in 1660. But this created an outcry that reached the

King in England who finally gave the order to cease all such

punishments for mere questions of faith. |

William Penn

|

William Penn

Ultimately Pennsylvania would become the real center of the Quaker faith in America because of the work of one man, William Penn. William Penn was born to the ranks of English aristocracy, his father being a prominent admiral in Charles II's navy and in fact one of the key agents in the return of England to monarchical rule under Charles. His father had high hopes for William as a leading soldier and politician in royalist England. But William was of a strong philosophical bent (much to the distress of his father), and very sensitive to the suffering that was going on outside of England's palace walls (the 1665 return of the plague and the 1666 Great Fire which destroyed most of London and left the population destitute). William's natural curiosity had him begin to associate himself with the Quakers, which ultimately drew an eight-month prison sentence for William (among several other prison terms he experienced in his lifetime), despite his family's high political connections. Miraculously, at his father's deathbed father and son were reconciled, in fact his father telling William never to betray what his conscience knew to be true. With his father's death in 1670 Penn came into a huge fortune, which he began to put to use to advance the Quaker cause. This is what led him to become part of a group of Quaker investors in the West Jersey colony in 1677. Penn then grew interested in the land that lay to the West of the West Jersey colony and began to press Charles to grant him land rights there as additional territory for settlement. The area in theory belonged to Charles's brother, James. But a deal was finally worked out in 1681 in which James would give up claim to the western territory as part of his New York which would then come into Penn's hands in 1681 in return for the forgiveness of a huge debt owed by the king to the Penn estate. Thus it was that Pennsylvania (meaning Penn's Woods – a name chosen by the king himself) came into being. Penn intended to make his colony a model colony of town planning, social reform, and high moral standards. In 1682 he came to his American colony to supervise personally the drafting for Pennsylvania of a Frame of Government which provided for an elected assembly for the colony. He also guaranteed a whole list of personal rights, including total freedom of religion in the colony (these were formally summed up in a Charter of Liberties which he drew up in 1701). And he personally laid out his carefully planned capital city Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, on a square grid pattern between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. He was also careful to give financial compensation to the Indians for the land, and blessed his colony with peace with the Indians as a result. Soon English Quakers arrived in large numbers, along with also French Huguenots (Calvinists like the Puritans), Mennonites and Amish (German Protestant Pietists), and Catholics and Jews from all over Europe. Pennsylvania was a place where all religious groups were invited to settle in the hope of finding finally a life of peace and prosperity. Actually it never reached the state of perfection that Penn had hoped for, in no small part due to the fact that the Quakers themselves could not agree as to what their new religion actually constituted, or how it was to respond to a number of threats to the colony's very existence. Ultimately, Quaker rivalries proved very disruptive to the Quaker order Penn was trying to achieve. Furthermore, as with the Jersey colony, the colony did not truly prosper its proprietor. This was in part due to Penn's inability to collect the tenants' quitrent, in part due to his overgenerous nature in extending loans to too many people, and in great part due to too much confidence in his business manager, who cheated Penn out of much of the profitability of the colony. Tragically, he ended up briefly once again in prison as a huge debtor. Although Penn died penniless in 1718 (previously believing himself and his Quaker project to have been a failure) his efforts at building a welcoming model colony ultimately helped to prosper Pennsylvania greatly, both materially and culturally.

Delaware

Three counties extending along the lower western shore of the Delaware River constituted a matter of title dispute between the Penn and the Calvert (Maryland) proprietors. The issue was finally settled by the king in 1682 when the area was recognized as part of Penn's colony. But these three counties, though possessing the same governor (appointed by Penn) as Pennsylvania, were handled differently, eventually (1704) possessing their own assembly to advise the governor. Effectively Delaware was a separate colony under the same proprietorship as Pennsylvania and with much the same freedom as its sister colony. |

Pennsylvania

Academy of

the Fine Arts

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges