|

|

Southern culture continues to pursue its aristocratic dream Southern culture continues to pursue its aristocratic dream  Georgia – the last of the original thirteen colonies Georgia – the last of the original thirteen colonies  A "Great Awakening" restores the Christian spirit in the colonies A "Great Awakening" restores the Christian spirit in the colonies  Colonial population and culture Colonial population and culture The economic growth of the colonies The economic growth of the colonies Colonial government Colonial governmentThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 98-105. |

|

|

In the American South, the passing of time merely fortified the

feudal-like distinction between the firmly established Southern gentry,

which increasingly took on the appearance and behavior of English

aristocracy, and the poor White dirt farmers living precariously along

the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains that rose abruptly to the

West of the open, fertile fields of Tidewater Virginia and Maryland.

And then there was the matter of the thousands of African slaves,

having no freedom to plan a life at all, always treated simply as

saleable property. Such oppression of masses of human souls made the

Cinderella dream of the Southern aristocracy very fragile. Also,

whereas some efforts had been made to introduce some of the Indian

neighbors to Christianity, there was virtually no interest in doing the

same for the African slaves. Christianity would have to wait a bit

longer before it would offer its spiritual counsel to these pitiful

slaves.

A Classic Example of the Southern Gentleman: William Byrd II

The Virginian, William Byrd II, exemplified the aristocratic nature of those who dominated Virginian life during these formative years of the colony. William II was born in 1674 on his father William I's huge Belvedere Estate (later known as the Westover Plantation) near the modern site of Richmond, further up the James River from Jamestown. As was typical of the Virginia nobility, the young William was sent off to England (age seven) for schooling while living with relatives there. Here for nine years he studied classic and modern European languages and literature. He then apprenticed in London and Rotterdam in the tobacco trade before taking up the study of law at the Middle Temple, London, in 1692. He was admitted to the bar in 1695 and, complements of the support of family friend Sir Robert Southwell, elected to the Royal Society in 1696. In 1696 he also returned to his native Virginia, which he had not seen in seventeen years. Here, with his aristocratic father's urging and backing, William was elected to the House of Burgesses, representing Henrico county. But finding colonial life lacking the sparkle of English social life, William soon resigned his position and returned to England to practice law. In 1698 he received the appointment as London Agent of the Virginia Governor's Council (the upper chamber of the Virginia House of Burgesses), thus now entitled to the prestigious rank of colonel. However, in this position he became deeply involved in political tensions arising between his father and Virginia Governor Nicholson (the Byrds had been supporters of the ousted former governor, Sir Edmund Andros). His four years at this position made him a somewhat cynical observer of political behavior. lso this aspiring young colonel found that despite all his close study and discipline in the graces of the English aristocracy, he suffered from the incurable social disease of being a mere colonial, and was never accepted into English society on an equal footing, despite his many social accomplishments. Thus in hearing of his father's death in 1705, he returned to Virginia to take up the responsibilities of running the huge estate he had just inherited. Those responsibilities included not only supervising the vast production of tobacco by hundreds of slaves, but of representing the Westover Plantation in all its power and social grace to the society of Virginian aristocracy. In this he was well prepared, complements of his years of (unsuccessful) effort in London to achieve entrance into English aristocracy. In 1709 he was appointed to the Governor's Council in the Virginia capital of Williamsburg. He found a wife from colonial society (daughter of Colonel Daniel Parke II, governor of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean), Lucy Parke. This high-spirited young lady was a perfect social match for William, though not untypical of high society at that time, William was reputed to be having alliances with a number of other women during their ten-year marriage. In 1715 Lucy died of smallpox. William would remarry eight years later. From this second marriage William III would be born. This Virginia taskmaster could be tough on his slaves (beatings of slaves for even minor infractions was normal procedure) but also on himself. He rode hard, ventured into the Virginia wilderness to survey the boundary line between Virginia and North Carolina, founded the town of Richmond, and kept himself well-read on all the latest literature, which he added to his classic collection – around 4,000 books in his personal library, which he considered to be nearly sacred ground. He even took up writing book-length studies, most notably his adventures during the Virginia-North Carolina surveying expedition. When he died in 1744 he left to his son William III family landholdings which at this point totaled almost 180,000 acres. |

|

| The

last of the American colonies, Georgia, chartered by King George in

1732, was quite different in conception from the others. It was not

designed originally as either a place of religious refuge or a

money-making venture, though certainly it was hoped that the Georgia

colony would be able to cover its expenses. It was primarily a military

colony, with the additional idea in mind that it could be a place to

resettle England's poor, languishing in England's prisons because of

debt.

The main inspiration for the colony came from English General James Oglethorpe, who had been involved in the War of Spanish succession (1701-1713). Although the question of which family should rule Spain had been resolved back in Europe, other questions, including the issue of what exactly were Spain's rights in North America, were still open. Thus trouble from Spanish Florida was expected. Consequently, a fortified colony south of Charleston and north of Florida was seen as a military necessity. Oglethorpe, as a member of Parliament, had been involved in a study of the conditions in England's debtors' prisons – which he found appalling and little likely to improve the lot of a debtor. So the idea emerged of using this proposed military colony as a place to help debtors get out from under an impossible situation. Oglethorpe and a group of fellow philanthropists thus petitioned King George for just such a colony (1732). The plans were to build forts along the coast of this new colony of Georgia and to locate the colony's capital city (constructed in a very well laid out grid pattern) at the mouth of the Savannah River. Blacks and Catholics were excluded from the colony (during only its very first years) in the hope of ensuring against any danger of religious and racial turmoil. Actually, very few debtors made their way to the colony. But it soon became a place of refuge for religious minorities from the continent of Europe, and for English tradesmen hoping for a better start in life. Still, the tight supervisory mindset that was supposed to get the colony off in the right direction seemed to discourage a great number of settlers from heading to Georgia. Most new settlers preferred to head instead to the less restrictive Carolinas. Only after the various laws regulating the character and behavior of the settlers were lifted did the colony begin to receive a large number of settlers. Then (by 1750) the colony began to take on the cultural flavor of nearby South Carolina, and the capital city Savannah some of the character of Charleston. |

General Oglethorpe meets with the Yamacraw Indians upon his arrival at the Georgia colony (1733)

|

| Then

around 1740, just as it appeared that the Christian foundations of

early America were about to die out for lack of spiritual interest or

even cultural support, something mysterious infected the American

heart. The "Great Awakening"1 suddenly broke out upon the American

scene to restore the warmth of American affection for God and Jesus –

and the belief again in God's full sovereignty in America.

This involved an enormous religious revival, drawing thousands of Americans who gathered in open fields to hear evangelists call them back to the old-time religion that their Puritan ancestors had known Christianity to be. This not only rekindled the American sense of being a Covenant people, but in the process revitalized the American sense of the basic equality of all people because according to these revivalist preachers (and the Puritan fathers before them) in the eyes of God all people were indeed equal.

Freylinghuysen and the Tennents

Actually, something of this strong revivalist nature had started some dozen years earlier (1725-1726), just here and there in New England and in the Middle Colonies. Theodore Frelinghuysen had been given the task of pastoring a number of small Dutch Reformed Churches in the Raritan Valley of New Jersey. He understood his central responsibility was to bring the wandering Christian souls back in line with a faith rather than works approach to their Christian life. He issued a strong call to the faithful for repentance, and a return to God as the guiding force in their lives. This call challenged them to take up something much more rigorous than just regular church attendance and proper Christian moral behavior. This was a call for a deep renewal of the people's faith in God personally as director of their lives. Something of the same nature was going on at about the same time in nearby Central New Jersey. William Tennent and his sons, particularly Gilbert, found themselves deeply committed to issuing to the Presbyterian congregations of the area a similar evangelical call to spiritual repentance and revival of their Christian faith. 1The

term "Great Awakening" was first applied to this event with the

publication in 1845 of Joseph Tracey's book, The Great Awakening: A

History of the Revival of Religion in the Time of Edwards and

Whitefield. |

| In 1746 the college was moved to New Jersey (ultimately Princeton in 1756) by the younger Gilbert and Jonathan Dickinson ... becoming the College of New Jersey (one-sixth of the Framers of the US Constitution were graduates of this College) ... changing its name in 1896 to Princeton University. |

|

Likewise, to the north in New England,

elements of a similar spiritual revival were undertaken during the

mid-1730s by Jonathan Edwards at his quite large Congregationalist

church in Northampton, Massachusetts. There was a deep earnestness on

Edward's part concerning the sinfulness of the faithful and the need

for repentance, which stirred the emotions deeply of his congregation.

Some 300 people were brought into fellowship with Edwards' congregation

during that period.

But all the emotionalism of such Christian revival began to stir the ire of some of the other pastors of New England and the Middle Colonies. And briefly it appeared that the whole thing would soon die away. |

|

George Whitefield and the Wesleys

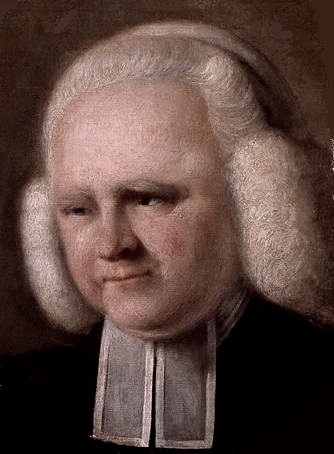

Meanwhile across the Atlantic in England something of the same nature was taking place, led principally by the English Calvinist reformer George Whitefield (pronounced Whit-field) and his close friends, the Anglican reformers2 John and Charles Wesley. They developed their close relationship (despite some theological differences) during their years at Oxford University where they created and led the Holy Club – before, at different points in time, heading off as pastors for a couple of years to the colony of Georgia to be part of the philanthropic idealism that supposedly had founded this new colony. But John Wesley would soon return to England after rather uninspiring efforts in Georgia, something that broke Wesley's heart. But this humbling experience in turn opened him to a truly born-again experience. Soon a spirit of revival rather dramatically took hold of both Wesley's and Whitefield's ministries. In 1739 this spirit took at first Whitefield and then John Wesley out into open fields to preach the message of salvation to the English working class. Such open-air preaching was a dramatic departure from the type of pulpit preaching expected of pastors. But while this irritated some of the Christian faithful, it succeeded in reaching thousands of people who otherwise would never have found themselves inside a church except for a wedding or a funeral. Something new was happening here! In 1740 Whitefield returned to Georgia to found an orphanage – and then moved on to Pennsylvania to do the same there (in partnership with some Moravians), also preaching every day as he made his way across the colonies. Gradually word began to spread among the colonies about this revivalist preacher Whitefield who was invited (as was customary) to preach in various churches along the way. Meanwhile, Tennent and Edwards linked up with Whitefield, inviting Whitefield to New Jersey and New England to preach there. With this, full revival began to break out, not just in Northampton and Central New Jersey but at various points throughout the colonies – as Whitefield now preached his way from New England in the north to Georgia in the South. Thus Whitefield found that his mission was no longer orphanages but simply a continuation of his preaching, wherever the Spirit directed his path. But having found it also easy in England to preach in open-air settings (fields and town squares), he proceeded to do the same in America. For some, this was quite a bit too much and now he found some church doors closing on him. But he continued to preach open-air style anyway.3 2Or

"Methodists" as they had previously been termed contemptuously by their

peers in their college days, because of the spiritual disciplines they

put themselves under in order to strengthen their faith and to support

their work. John was the evangelical preacher and organizer,

Charles the writer of popular hymns ... such as "Hark, the Herald

Angels Sing," and "Christ the Lord is Ris'n Today." 3While

Whitefield was busy developing Christian revival in America, his friend

John Wesley was busy doing the same in England, thus founding there

what was to become the Methodist movement. Eventually (1760 and after)

Wesley's Methodist movement would come to America – still considering

itself an integral part of the Church of England and under its

discipline. But in 1784, with America's break from England following

its War of Independence, the Wesleyan or "Methodist" movement in

America would reform itself as the Methodist Episcopal Church, coming

under its own bishops, Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury. At this point

the Methodist Church would truly take off as a massive revival

movement, especially as a result of the extensive work of the Methodist

circuit riders who carried the spirit of revival to the rapidly

expanding American frontier – making it a part of the "Second Great

Awakening" that shook the young Republic in its early years (1790s to

mid–1800s). |

|

The Impact of the Great Awakening

Edwards himself became a major figure in this broader revival, with his preaching in 1741 in his church in Massachusetts and then again in Connecticut his famous sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." Although Edwards did not take up the fiery style of Whitefield, his calmly presented sermons had much the same effect on his listeners: repentance and the call to salvation. The effect of this revivalist preaching was overwhelming. Revival swept like a whirlwind everywhere throughout the colonies, especially in the years 1741-1743. This first truly all-American event went far not only in restoring a deep spirituality in America but also giving the colonists from the North to the South a sense of being a unique people, something akin to a nation. Americans now had national heroes as Americans, revivalists and missionaries well known up and down the colonies as part of the common experience of American life. Whitefield became very well-known from Maine to Georgia, moving up and down the American colonies over the course of the thirty-two-year period (1738-1770) when he visited America numerous times to preach revival. Also the heroic story of the young Presbyterian missionary (and friend of Edwards), David Brainerd, who wore himself out (tuberculosis) preaching a similar revival to the Indians, was well known across the colonies, making him something of a national hero. And the Presbyterian minister Samuel Davies became a powerful instrument in reaching not only frontiersmen but also African slaves in Virginia with the gospel message. Furthermore, the sermons of the revivalist preachers (especially Edwards' sermons) were read widely throughout the colonies. The message of this revival was clear and unvarying: God was calling the Americans out of their spiritual slumber to a repentance that would prepare them for a great work ahead of them. As citizens of the New World they had a huge calling on their lives from God to be his people as he, their one and only sovereign, led them. In taking up this call they would show the Old World of Europe, by America's own example, how a people could live to a new and glorious purpose in Christ. Consequently, such a message repeated over and over again worked strongly to build something of a national spirit – a collective identity among the colonists as "Americans." |

|

Opposition to the New Style

Not every American got swept up in this Awakening. There were many hostile critics among the American intellectuals who found this phenomenon most improper. Unfortunately, the excitement of the new style led some enthusiastic pastors to go overboard in that enthusiasm. For instance, James Davenport went all out not only in viciously attacking people who had not embraced fully the revival, but going through strange emotional highs himself publicly (possibly suffering from bouts of insanity) in the service of his cause, which made it easy to be very critical of the excessive enthusiasm of that cause. Indeed, for many of the Old Light Christians (led by the Boston pastor Charles Chauncy),4 revivalists preaching emotionally charged sermons in open fields before thousands of common farmers and tradesmen and women – rather than to parishioners properly attired in their Sunday finery and seated properly in their pews in church attentive to the theological details of a scholarly sermon – was just not proper Christianity. Worse, such proper church-going Christians being called out by the revivalists as sinners needing the forgiveness of God no less than the sinners of the inferior social ranks was considered by those proper Christians as an outrageous idea, even an evil idea inspired by the Deceiver, Satan himself. Then too, many pastors were simply bitterly jealous that while their churches remained empty, hundreds – even thousands – of people found it easy enough to gather in nearby fields to hear the preachers of spiritual revival.5 But these critics were a small voice in the scheme of things.6 4But Old Light Chauncy would be just as outspoken in his opposition when talk began to develop (the beginning of the 1770s) in England about placing the colonial churches of America under episcopal authority (rule by bishops and archbishops – and ultimately the king of England himself) of the Church of England. In fact Chauncy's sermons and pamphlets in support of the colonies' War of Independence against England were widely influential in the colonies. 5A split in 1741 opened up also within the Presbyterian denomination (heavily concentrated at the time in the middle colonies of New Jersey and Pennsylvania) between the New Side and Old Side over the ordination of pastors graduating from Gilbert Tennent's "Log College" (forerunner of Princeton Seminary). New Siders were pro-revivalist pastors, whose numbers increased dramatically – just as the Old Side pastors numbers declined equally dramatically. 6Sadly

for Edwards, opposition to his style and message eventually developed

within his own church, and in 1750 he was voted out of his pulpit by a

quite large majority. He took himself off to preach to the Indians (but

still writing at the same time). But he was not forgotten in the larger

American world and in 1758 he was called to the presidency of the

Presbyterian New Sider's College of New Jersey (the future Princeton |

|

Ben Franklin's Take on the Matter

Even the greatest American sage of the time, Ben Franklin, found himself warmed at least intellectually by this massive religious revival. In fact, he personally saw to the publishing of forty or more of Whitefield's sermons on the front page of his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette. Indeed, Franklin and Whitefield formed a friendship that lasted the entire span of Whitefield's remaining life (he died in 1770). God knew that the Americans would need this preparation for the days ahead when troubles would mount between the Americans and the powers of Europe (and also the native Indians). No amount of intellectual Rationalism would give courage to the American colonials, who understood the sacrifices they were called to in taking up the path of rebellion against their king, and the hangman's noose that awaited them as traitors if this rebellion should fail. Americans were going to need a strong faith in God's support in order not to lose courage in the face of these deadly challenges. And so it was that the Great Awakening was well timed to bring exactly such spiritual preparation. God was being faithful to keep his side of the Covenant with America. |

|

Library Company of

Philadelphia

Collection of Albert F.

Smiley

painted by John Singleton

Copley in 1775

Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

|

Massachusetts Historical

Society

The Great Wagon Road

(by 1776 it was a busy seaport

and the 9th largest city in the colonies)

New York Public

Library

Clements Library

National Gallery of

Art

|

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges