|

|

A growing sense of separate "American" destiny A growing sense of separate "American" destiny  Europe's dynastic wars Europe's dynastic wars The French and Indian War (1754-1763) [Europe: the Seven Years' War] The French and Indian War (1754-1763) [Europe: the Seven Years' War] The Albany Plan: An early attempt at colonial unity The Albany Plan: An early attempt at colonial unityThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 106-112. |

|

|

Certainly the American colonists knew that they were Englishmen. But

they also knew that they were a very different kind of Englishmen than

the ones back in the Mother country. It is not that they were first and

foremost Americans. They would have seen themselves first as

Virginians, or New Yorkers, or Pennsylvanians, etc. But life

collectively on the opposite side of the Atlantic from the Mother

Country was beginning

to have a unique effect on their social self-perceptions.

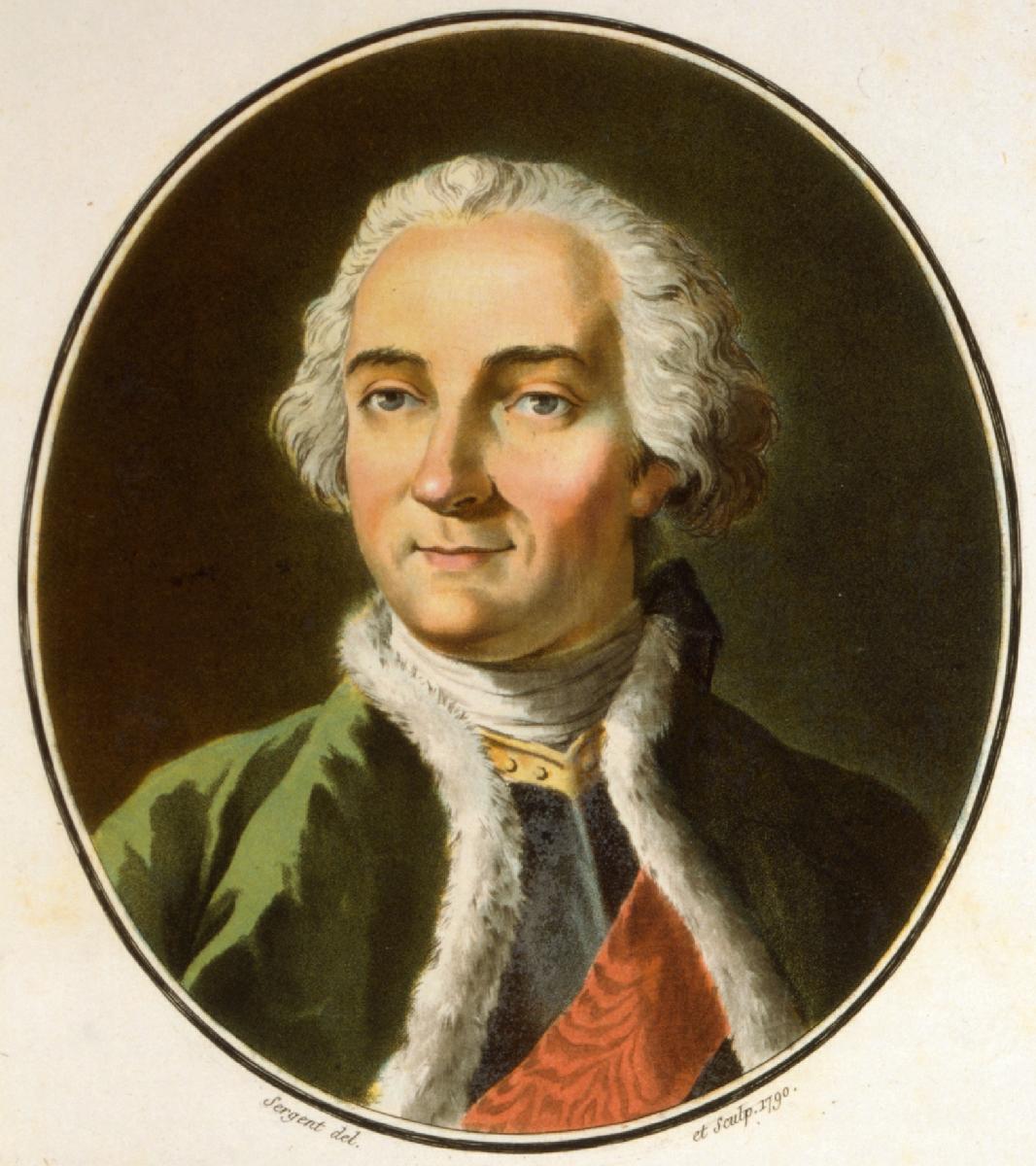

The New Hanoverian Kings of England

With the expiring of the Stuart dynasty in 1714 - and the need of England to go all the way to Germany to fetch a new English king (a distant cousin from the Hanoverian branch of the family), the sense of distance between America and England would begin to grow. We have already noted that George I (1714-1727) and his son George II (1727-1760) were truly German rather than English and tended to isolate themselves in their own familiar world (hunting and sporting), leaving politics to political advisers who understood English ways (and the English language) better than they. Also they were as interested in European events involving the status of their German holdings in Hanover as they were interested in things English, including the affairs of colonial America. In short, they tended to look much more eastward toward continental Europe (and all the dynastic quarrels going on there) than westward across the Atlantic to what was going on in America. This kind of political neglect by the English kings in the period of 1714-1760 thus strengthened the sense of a going-it-alone in the colonies. Those years gave American colonials a chance to develop even further a strong sense of independence and political self-sufficiency. |

|

|

Dynastic wars among European monarchs were constant, involving ruling families in one war after another in unbroken succession. These wars naturally included the dynastic holdings in colonial America (as well as Asia) and thus the American colonies would get involved in one way or another. However, the colonial perspective on these conflicts differed from the European perspective, being fought in America around local interests of the English, French and Spanish, and usually drawing the Indians into the conflicts on one side or the other. A few of these wars stand out because they touched the colonies deeply. Naturally, where possible, the colonists tried to stay out of the affairs that embroiled European politics. They were, of course, always well aware of the struggles going on back in Europe. But the distance from those events gave the colonists a distinct view or take on them. The colonists were naturally more focused on things closer to home, such as the ongoing troubles with the Indians, and the expansion of the Catholic French into the lands to the West of the Appalachian Mountains, where the Americans were beginning to look for their own expansion. Then there was also the potential threat from the Catholic Spanish to the south of the colonies. But in the end, the colonies could not avoid getting involved in the ongoing dynastic struggles between the monarchies of England, France, Spain, Portugal, Austria, and Prussia – and the Netherlands (which was not a monarchy but rather something more like a republic, but which was caught up in the conflicts nonetheless). Mostly these wars involved the English against the French (always) and the Spanish (frequently). And these European contests had a way of spilling over into the colonies, forcing the colonies to work together to defend themselves militarily. But this too would add to the growing sense of the colonists that they were not only Virginians or New Yorkers, but also Americans.

Queen Anne's War1

[Europe: the War of Spanish Succession] (1701-1713) This war was fought in Europe over the possibility of a French Bourbon prince, Philip V, becoming the King of Spain (the Habsburg dynasty in Spain finally having expired without an heir). Philip was the grandson of the French Bourbon King Louis XIV and thus also in line to eventually become the King of France. The thought that these two large countries should come under the rule of one person was frightening to much of the rest of Europe, especially the English. A general coalition against the French and Spanish thus gathered and war broke out in 1701. The final result (the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713) was most importantly that Philip renounced his claim to the French throne and thus became only the King of Spain. In the colonies, the English forces made up of Royal troops, colonial militia, and their Indian allies, found themselves fully occupied with fighting along the frontiers both in the North, against the French and their Indian allies – and in the South, against the Spanish and their Indian allies. The fighting was rather constant, ferocious, and inconclusive. English and French forts, towns and farming communities, plus Indian villages were attacked here and there, with first one side then the other gaining a brief advantage – or nobody gaining a victory from the effort. The mighty Iroquois Indian confederation (positioned principally in northern and western New York) insisted on remaining neutral between the French and English, though sometimes the Iroquois gave minor aid to the French or to the English. Mostly the French and English avoided passing through Iroquois territory in order not to upset the neutrality of this strong Indian confederation. In the end, according to the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht, the French lost to the English their scattered French-Canadian settlements in Newfoundland and the more built-up French-Canadian coastal region of Acadia (Southeastern Quebec). The effect for the Acadian French was the forced Anglicizing of both their Catholic religion and French culture, which would remain a constant sore point for the Acadians, and in the eyes of the English leave the Acadians as questionable citizens within the British Empire. In the south (in the future Georgia and in Spanish Florida) in addition to the raiding and destruction of coastal settlements of both the English and Spanish (including Spanish Catholic mission stations), the war turned out to be mostly a war of Indian against Indian, tribes being drawn into mutual conflict as allies of either the English or Spanish. The net result was the huge loss of Indian life in the South – in Spanish Florida and in what would become southern Georgia. The Treaty of Utrecht ultimately changed little in the southern political picture. But the Spanish were hit so hard in Florida that they never were really able to recover their position there physically. Ultimately, continuing trouble with Spain in this region was what convinced English King George in 1732 to support Oglethorpe and his associates in their effort to found the English colony of Georgia. The War of Jenkins' Ear2 (1739-1742)

This war was fought between England and Spain, largely over the English right to sell slaves and other goods (for the limited period of thirty years) in the Spanish colonies as part of the terms of the earlier 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. By the late 1730s both sides claimed that the other party was not properly respecting the asiento (agreement or contract) and war broke out in 1739. The English played the war cautiously, not wanting English success against the Spanish to draw the French into the war on the side of the Spanish. The war itself proved nothing in America as well as in Europe. Oglethorpe's effort to take Spanish St. Augustine in Florida failed (1740), as did a Spanish attack on Georgia (1742). King George's War

[Europe: The War of Austrian Succession] (1744-1748) This war was fought in Europe ostensibly over the question of the right of a woman, Maria Theresa of Habsburg, to the Imperial throne of the Holy Roman Empire (Austria). Actually, it was part of the on-going dynastic struggle among the Bourbon French, the newly Bourbon Spanish, the Habsburg Austrians, and the Hanoverian English for control of particular borderlands here and there in Europe. But the war introduced a new major player in the dynastic game, Hohenzollern Prussia, under the rule of the very capable Frederick (the Great). France allied with German Prussia in the hopes of further undermining its ancient foe, the Austrian Habsburgs. But Frederick was more interested in the borderlands (Silesia) between Prussia and Austria. In the end – and after much expensive, devastating, and inconclusive battling among nearly all the European monarchs – only Prussia really came out of the war with a true gain (Silesia). France got nothing for its costly efforts except the emptying of the French royal treasury and the deepening of the indebtedness of the French king still trying to cover the costs of his military adventures. Austria got to keep Maria Theresa in place as Austrian empress. But Germany would now and for the next century be the cockpit for an ongoing struggle between Austria and Prussia for ascendancy over the many states that made up the land of Germany – which eventually Prussia would win, becoming the centerpiece (1870) for a new German nation. As for the English colonists in America, the war brought frustration when the vital French fortress of Louisbourg, located on an island at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River and thus guarding the maritime entrance to French Canada, was returned to the French in 1748 as part of the final peace settlement (the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle). Louisbourg had been captured by American colonial troops at some serious cost to those American troops. But American political interests were of no particular concern to the English monarch, whose sole interest at the time (as with all European dynasties) was how such peace terms played to the political advantage of his own dynasty. 1Interestingly, these wars were usually known in the colonies by a name which differed from the one used by Europeans! 2English

sea captain Robert Jenkins lost his ear in a struggle when the Spanish

boarded his ship in 1731 to block the selling of slaves in the Spanish

Americas. The displaying of his severed ear in Parliament eventually

stirred the English to go to war against the Spanish. Actually, this

smaller conflict helped set the stage for the outbreak in 1744 of the

larger War of Austrian Succession. |

R.A.Nonenmacher (modified

slightly)

Wikipedia - "French and

Indian Wars"

Pocumtuck Valley Memorial

Association

Wikipedia - "Colonial history

of the United States"

New York Historical

Society

|

(The French and Indian War)

Hoodinski - Wikipedia - "French and Indian

War"

| This

war actually began in the colonies in 1754, a couple of years before it

drew the major European powers into full-blown war in 1756. It also

actually phased out in the American colonies in 1760, several years

before it ended in Europe (and in Asia) in 1763.

The war began in America with a dispute between the French and English over the question of who had the rights to trade with the Indians in the Ohio region – a very complex issue made even more complex by the changing alliances of the Indians themselves – and more specifically over the colonial boundary running along the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers (where Pittsburgh is located today). A Virginia officer (major) named George Washington and the colonial troops under his command, sent to establish Virginia's claim to the area, clashed with and defeated a small French force there in May of 1754. Washington then proceeded to build a small fort (Fort Necessity) to defend Virginia's claim to the area. But the fort was soon (that July) lost to the French ... Washington's first of a long string of defeats! The following year (1755), British General Edward Braddock – joined by Washington – returned to the area to try to seize the French Fort Duquesne, but failed in the attempt. Braddock and his troops were then mauled by Indian allies of the French as his troops retreated. Braddock was killed, the French were tipped off as to British military plans for the entire region, and the British campaign of 1755 turned into a huge disaster. The only English success that year occurred in the Northeast when the French island fortress of Louisbourg once again fell into English hands. This event was accompanied by the tragedy falling on the Acadian French living in the area, distrusted (for good reasons) in their loyalties by the British authorities, who by the thousands were forcibly removed from the region. Beginning in 1755 and continuing until 1763, over 11,000 French-speaking Acadians were deported and scattered among the English colonies – around 2,000 losing their lives through exhaustion and disease in the process. Some returned to France and others made their way down the Mississippi to French Louisiana where they established a colony west of New Orleans, and thus a particular French-speaking culture there, namely that of the Cajuns (from the French Acadiens.) The next couple of years (1756-1757) did not go well for the English. The worst of the beating that the English took was in August of 1757 at Fort William Henry, along the southern shore of Lake George (New York). A small garrison of English soldiers protecting the Fort and the surrounding English settlement was besieged by the French under Montcalm and a Huron Indian force of over 2,000 (who had gathered from all around the Ohio Territory, even from beyond the Mississippi). The garrison surrendered under the promise of safe conduct extended to the soldiers and civilians departing south to Fort Edward. But as the English soldiers and settlers were making their way through the masses of French and Indians, the Indians set upon the defenseless English, killing and scalping and enslaving hundreds of the English – women and children as well as the men. News of the massacre spread rapidly through the colonies, further embittering settler feelings toward the Indians and making any idea of future friendly relations between the English settlers and the Indians all the more unlikely. In 1758 things finally began to turn in favor of the English. An English blockade against supplies reaching Quebec, a bad Canadian harvest in 1757, the outbreak of disease (including smallpox) among the French Canadians, and the decision of the French to try to divert the English from Canada by withdrawing troops from Canada in order to further strengthen their forces attempting a direct attack on England itself (which failed miserably), all greatly weakened the French position in North America. By 1759, the French were losing fortresses everywhere. The worst loss was Quebec, which fell in 1759 and took the lives of both the invading English commander Wolfe and the defending French commander Montcalm. The loss of Quebec then left Montreal vulnerable to English conquest. By 1760 the French were ready to admit defeat in America. Thus the American portion of the Seven-Years or French and Indian War was essentially over. For the Indians, who joined in on one side or the other, there was no gain whatsoever by their participation, but only the further weakening of the overall Indian position in the Ohio territory. Promises of security against the further expansion of Anglo settlements into Indian lands were made by the new British King George III (crowned in 1760) to his Indian allies. But these were not promises he was able to keep, and promises that only soured relations between him and his English subjects in America. Overall, the war was an international struggle among European dynasties which involved the participants in Europe itself, in the West Indies, and in Asia – as well as in North America. Though the war effectively ground to a halt in North America in 1760, it dragged on elsewhere. The final settlement was not concluded until 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. It involved the transfer of power back and forth among the dynasties not only in North America but also in much of the rest of the world, where the Europeans had been active establishing their presence with commercial colonies and trading centers. The results would make England the world's leading colonial power, with a global empire including significant sections of India, the Caribbean, and the African coast, as well as the Eastern half of the North American continent. The other net effect of the war was that it nearly bankrupted the participating European dynasties. The French, the English, and the Spanish 112 America – The Covenant Nation (Volume 1) kings found themselves deeply in debt at the end of the war and desperate for new funding (taxes) that could help them restore their respective royal treasuries. Monumental consequences would arise from the financial predicament in which the war placed the European monarchs. |

New York Public

Library

He laid a major road

westward to reach the French and Indian defenders in Fort

Duquesne

(Pittsburgh) he and his army were cut

down by the enemy in a battle on

July 9, 1755 when he refused to fight

from cover; he died 4 days later from

his wounds

State Historical Society

of Wisconsin

(burning in the distance) for resettlement in other

English colonies –

because of a distrust of

their loyalties to the English crown

New York Public

Library

Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto

Library of

Congress

New York Historical

Society

a portrait by Joshua

Reynolds

Collection of the Earl

Amherst

The Battle of Quebec – September 1759

Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto

Wikipedia

by Benjamin West

National Gallery of Canada,

Ottawa

and the Indian nations in the middle colonies

|

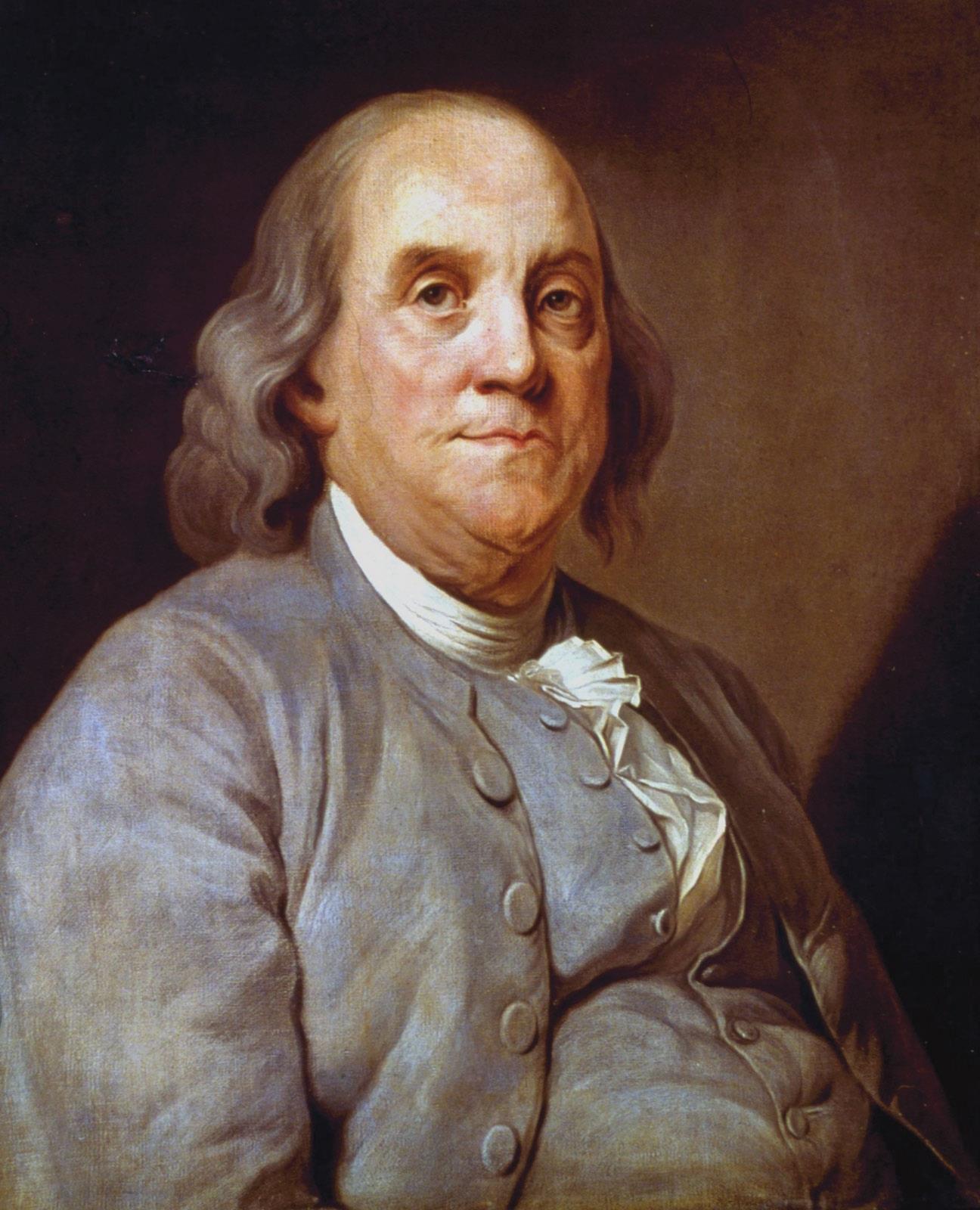

| With

the onset of the French and Indian War in 1754, the colonies once again

felt themselves in danger from the old threat of the French and their

Indian allies. Thus in that same year representatives from various

Middle and Upper Colonies gathered at Albany, New York, to discuss

joint action, including improved relations with their Indian allies.

Ben Franklin, who was one of the delegates, proposed a plan to unite

the English colonies on a more permanent basis. The Albany Plan

provided for an elective Grand Council (two to seven members sent from

each of the colonies) that had the power to commit the colonies jointly

in a limited number of political areas, most notably the colonies'

relations with the Indians. The Grand Council was to be headed by a

president, appointed by the king. The delegates approved this plan.

But their colonial assemblies did not, fearing the loss of colonial independence to this colony-wide authority. Such American unity would thus have to wait for a new day. |

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges