|

|

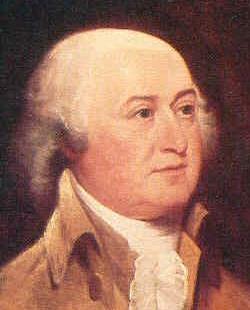

An ambitious young English king, George III (reigned 1760-1820) An ambitious young English king, George III (reigned 1760-1820) The colonial reaction to King George's autocratic ways The colonial reaction to King George's autocratic ways Meanwhile, the Westward expansion of Anglo-America continues Meanwhile, the Westward expansion of Anglo-America continuesThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 112-115. |

|

on colonial documents and papers (including newspapers)

New York Public

Library

|

Library of

Congress

|

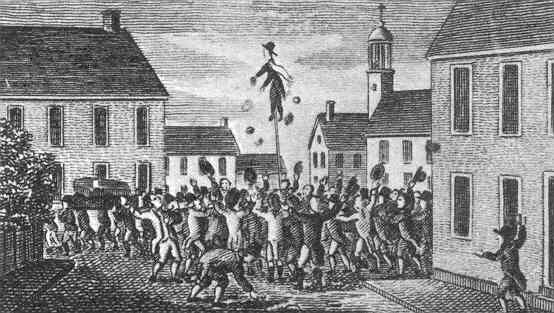

The 1765 Stamp Act

Worst of all was the fact that the first taxes to be collected would be from the revenue acquired by the purchase of official stamps or stamped paper, required to be printed on or attached to all colonial documents – even church documents. Boston Pastor Jonathan Mayhew preached a fiery sermon against this tax, claiming that this was a guise to establish royal control over the voice of the American church. The next day angry Bostonians burned down the home of the lieutenant governor. But the Virginians were no less outraged, and the burgesses, under the influence of Patrick Henry's oratory, voted a refusal to pay the taxes. British Parliament quickly repealed the Stamp Act (although other taxes would be imposed in place of the stamp tax). But the political damage was done. The Bostonians and Virginians demonstrated that they had no hesitation in rejecting the authority of the King in America if he overstepped the ancient rights of Englishmen. On this matter they even had supporters in the English parliament back in London, the Whigs, who agreed in principle with the colonists. But the king also had supporters in Parliament, the Tories, who agreed with the king, that he as sovereign had the right to make his subjects pay for the expenses of running the government. Thus beyond the issue of the costs involved in the war, the matter of high political principle dividing Whigs and Tories became a key part of the matter.

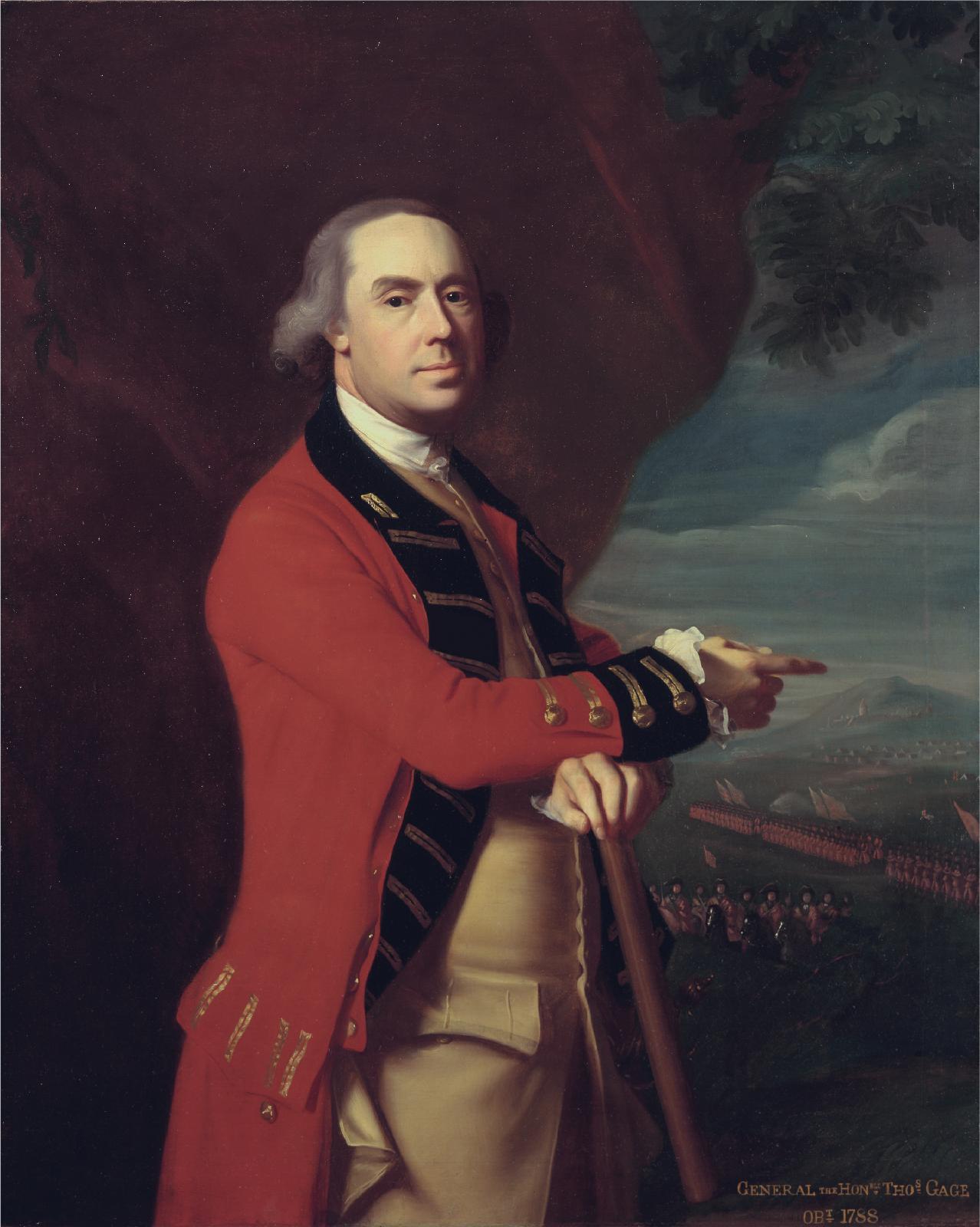

The 1770 Boston Massacre

The issue came to violence when an angry group of Bostonians began taunting British Redcoat soldiers stationed in Boston to protect British agents sent to collect the hated taxes. Nervous soldiers fired into the surrounding crowd, killing three and injuring eight (two of whom would subsequently die of their wounds). Volunteering to defend the soldiers was a dedicated lawyer (and future American president) John Adams. Six of the soldiers were acquitted and just two charged with manslaughter. This was a daring act on Adams's part, considering the temper of the city, but indicative of his moral integrity (or ambition) – which the nation would later recognize and call into service. Nonetheless, the event itself was an early indication of the mood that was developing in the colonies. |

Metropolitan Museum of

Art

by John Singleton Copley

Yale Center for British

Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Winterthur Museum

Metropolitan Museum of

Art

John Adams

He served as the defense lawyer for the Redcoats involved in the shooting

... actually launching his political career!

|

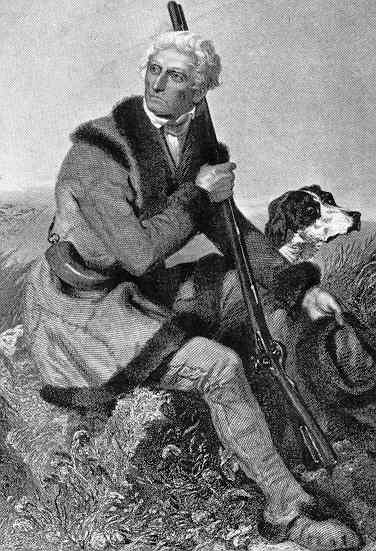

The English-Americans were not paying any attention to King George's promise

to his Indian allies that he would stop further expansion westward

into Indian lands by his Anglo colonial subjects

|

George III's Efforts to Halt the Spread West

of English Settlers into Indian Lands The colonists were also very unhappy that King George III had promised his Indian allies that, in recognition of their assistance in his war against the French (and France's Indian allies), no Anglo settlers would be allowed into the Indian lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The colonies had long assumed that their boundaries, never fully defined to the West, actually extended westward across the Appalachian Mountains – at least to the Mississippi River (or even beyond). Colonists had been looking westward in that direction with the expectation that these lands would become available as the lands in the East filled with settlers and their descendants. Indeed, in 1775 Daniel Boone had laid out his Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap in the Appalachian Mountains and had founded a settlement in Kentucky (subsequently named after him as Boonesborough). Thus the proposed restriction by the king on that expansion was a major irritant – if not even a direct threat – to the future well-being of the colonials. Along the same lines of logic as his promise to his Indian allies, George issued in 1774 a promise to his French subjects in Canada that their Catholic faith and French civil law would be recognized in a greatly expanded province of Quebec, a Quebec which now would include the territories to the West of the thirteen colonies on the other side of the Appalachian mountain range. What?!!! The king was now not only supporting Catholicism in principle but also moving to establish the Catholic church (and its bishops) as the spiritual governors in the colonies' Western territories. This move to support Catholicism in the Western lands, plus the king's talk of wanting to appoint Anglican bishops to oversee the religious life of the English colonies, appeared simply to be a ploy to bring the English colonials' highly cherished 150-year-old religious freedoms in America to an end. Even before this event, concern had been rising in New England over the missionary efforts of the king's Church of England, not to the unsaved in the colonies, but aimed at good Congregationalists in an effort to bring them under the Mother Church. Already, in the 1750s, the pastor-activist Mayhew had taken up the cause of fending off the efforts of the Church of England to absorb the independent churches of New England, and by 1762, when there was open talk about positioning Anglican bishops over the colonies, Mayhew did his best to stir the stiffest opposition to such an invasion of colonial religious rights. |

Tennessee State Library

and Archives

St. Louis, Washington University

Gallery of Art

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges