|

|

Rebellion in the colonies Rebellion in the colonies The first battles take place at Lexington and Concord outside of Boston The first battles take place at Lexington and Concord outside of Boston  The Second Continental Congress assembles in Philadelphia (1775) The Second Continental Congress assembles in Philadelphia (1775)The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 115-118. |

|

|

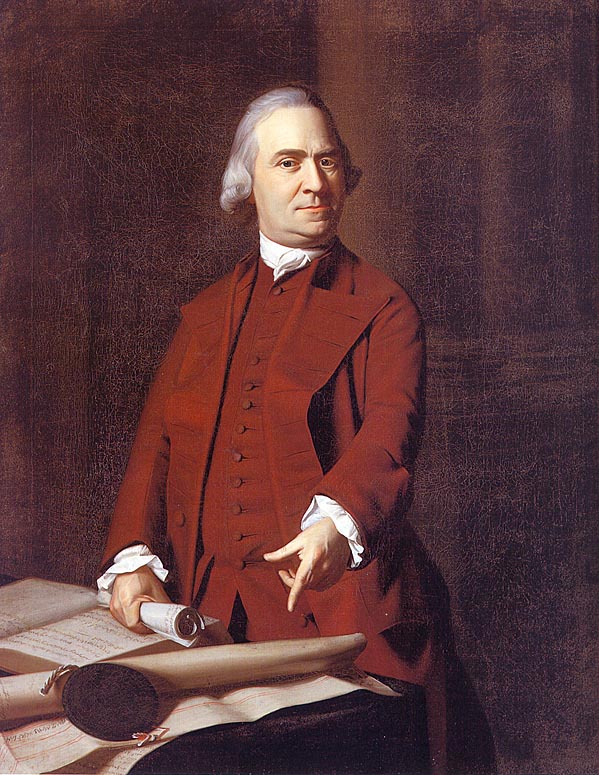

The Boston Tea Party (December 1773) – and the King's reaction

What actually caused a full-scale rebellion finally to break forth in the colonies was yet another issue: tea. This rebellion erupted with the move of Parliament to give financial support to the failing East India Company (the English victory in India had not brought the company the profits it was expecting) by way of a number of political maneuvers which not only gave monopoly rights of the company to trade with the colonies (the colonials could actually get tea much more cheaply from the Dutch) but also imposed new taxes on the company's tea. Protests that these taxes were unfair were met by a coldness on the part of the royal government, which had by the early 1770s come to believe that any backing down on this issue would simply encourage further the independent spirit of the king's American subjects. A major political explosion occurred in late 1773 with the arrival of a huge cargo of the company's tea sent to the colonies. In most cases Americans simply refused to unload the tea (New York, Philadelphia, Charleston). But in Boston the tea was dumped into the harbor in a great public show (directed by Samuel Adams) by Patriots dressed as Indians – stirring the wrath of the royal government. To demonstrate clearly the sovereignty of the king (and his heavily-Tory Parliament) in his colonies, the king's government enacted a number of Coercive or Intolerable Acts (1774) which basically shut down the port of Boston. The goal of the king was essentially to strangle the town's economy in order to bring the colonists back into submission. And to make doubly sure that the colonists got the point, the king sent a huge occupying force of British troops to Boston, and forced the townsmen to house these normally rowdy troops in their private homes – again, to break the independent spirit of his colonial subjects. However, George's efforts at coercion merely united the colonies more closely in a mood of continental solidarity (the other colonies sent considerable financial and material aid to a crippled Boston). Thus in 1774 a Continental Congress of representatives of the thirteen colonies gathered in Philadelphia to coordinate the colonies' efforts to get some relief from King George. But their efforts to change the heart of the king failed entirely. By early 1775 the spirit of rebellion was gathering momentum among the growing number of American Whigs or Patriots. Now it would take only a small spark to set off a full-scale explosion of colonial fury. |

Samuel Adams – painted by

John Singleton Copley

Boston, Museum of Fine

Arts

Paul Revere – painted by

John Singleton Copley

Boston, Museum of Fine

Arts

The Gaspee burning –

1772

Rhode Island Historical

Society

Rhode Islanders destroyed this British revenue ship

commissioned to stop smuggling in the Narragansett Bay

Abraham Whipple – Providence

merchant – 1772

U.S. Naval Academy

Museum

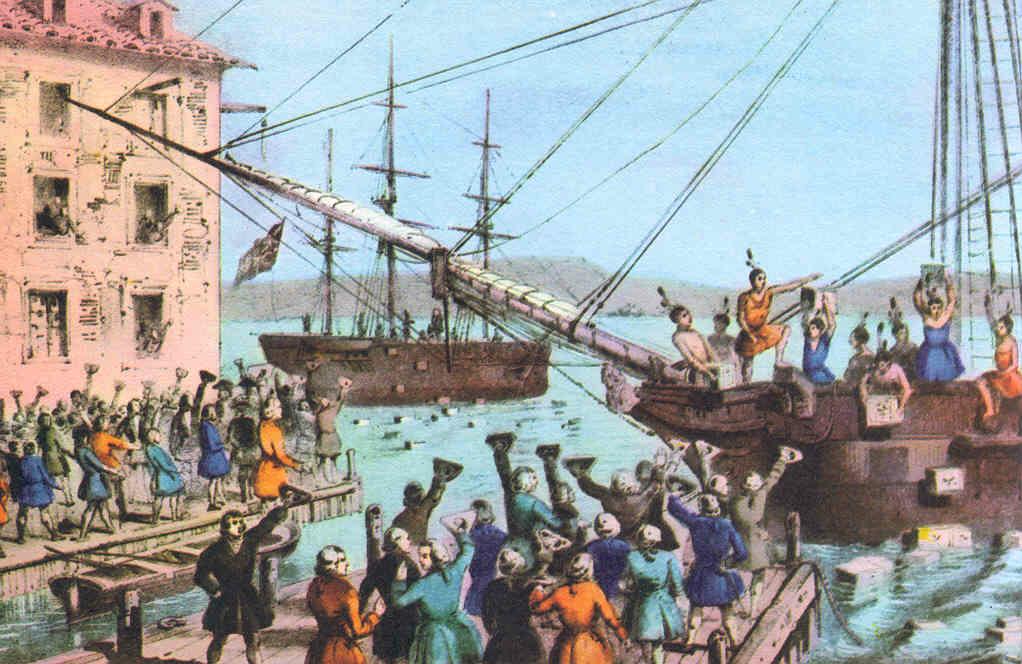

The Boston Tea Party – December

16, 1773

(actually a night-time

caper!)

Museum of the City of New

York

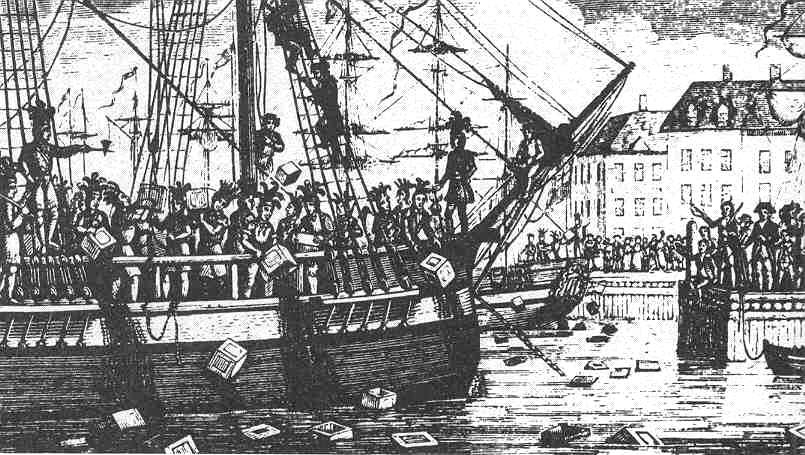

The Boston Tea Party – December

16, 1773

New York Public

Library

A cartoon lampooning American

liberties – 1774

John Carter Brown

Library

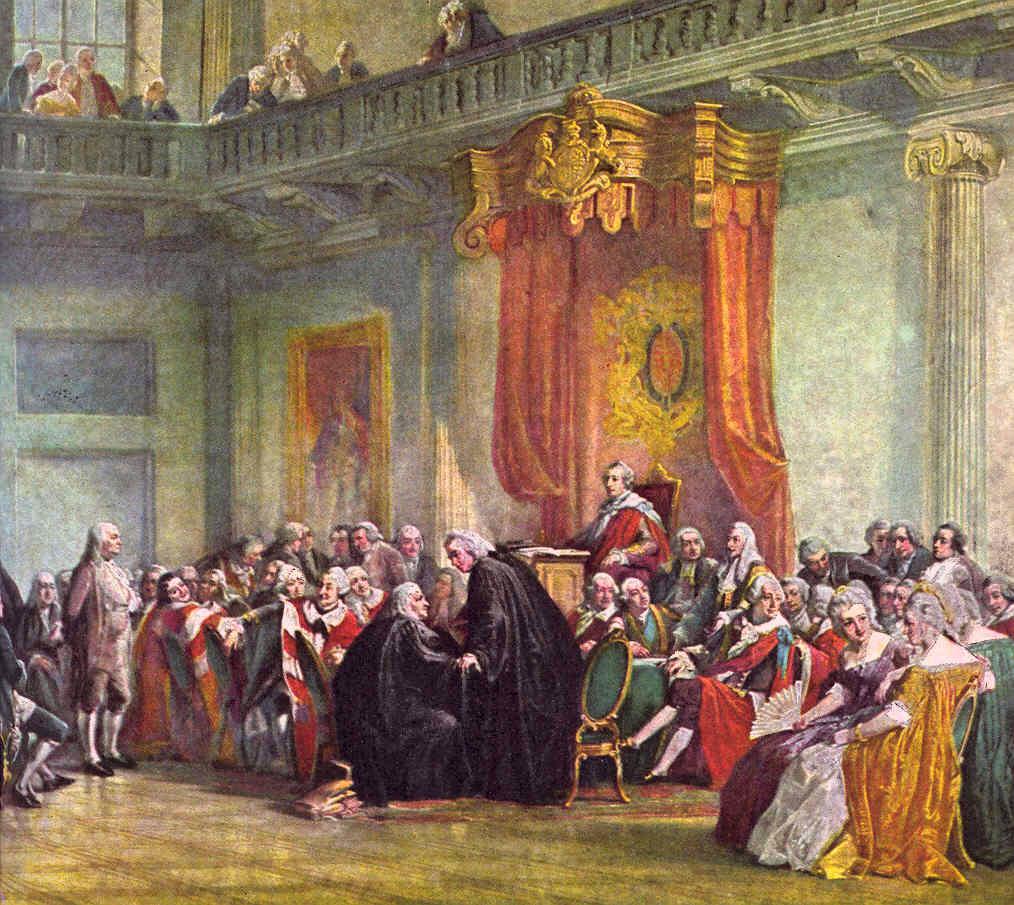

Ben Franklin before the Privy

Council – 1774

Huntington

Library

The First Continental Congress debating the proper response

to the ever-tightening grip of the King over American life (September-October 1774)

|

|

The Battles of Lexington and Concord (April 19, 1775)

As tensions mounted in the early spring of 1775 the British military in Boston decided that it would be best to disarm their colonial subjects – by seizing and destroying the stores of weapons and powder of the local militias. Thus in April a march of British troops was initiated by night from Boston to nearby Concord to seize military stores located there (however, these supplies had been mostly evacuated by the Americans who were tipped off about British plans). By dawn on the 19th, the troops had reached the town of Lexington, where American militia had quickly assembled to face the large British force.1 A shot rang out (no one knows by whom), the British charged the Americans (who were actually in the process of dispersing) and eight were killed (shot or bayoneted) and ten wounded. Thus the first shot of the War of Independence was fired. The British troops then moved on to Concord, where they were confronted by a rapidly increasing gathering of Massachusetts militia. Another fight broke out between the two sides at the North Bridge, except this time it was the British who took the blows. British troops did what they could to locate hidden supplies, destroyed what they found (not a significant amount) and then regrouped to head back to Boston, tired and shocked by the day's business. But the worst was yet to come. Militia had gathered along the route back to Boston and began to fire on the exhausted retreating British troops. British reinforcements subsequently arrived from Boston and then both sides began to take large casualties. But eventually the British made it back to Boston. The shooting had now started in full. It would continue for another seven deadly years. 1The

militias are frequently referred to as the minutemen, because they were

trained to assemble and move quickly, fully armed, normally to counter

a surprise Indian attack. |

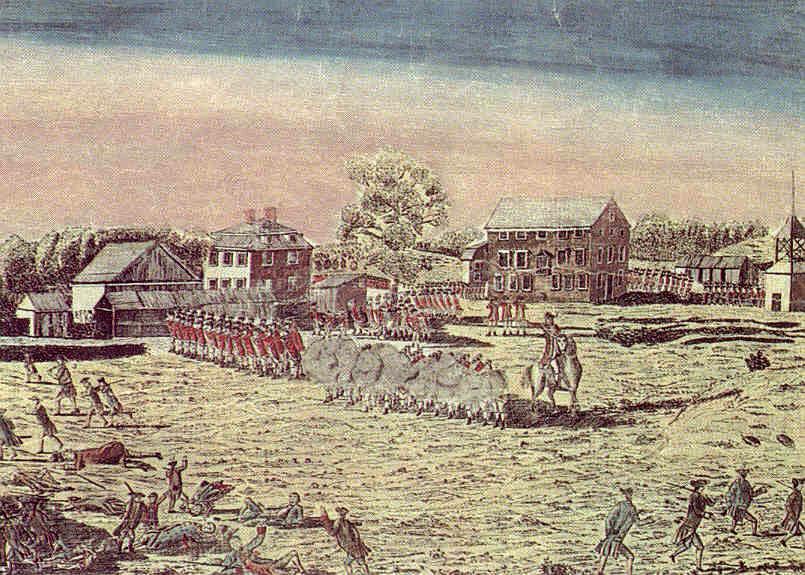

The Battle of

Lexington – the morning of April 19th, 1775

But later that morning at the North Bridge at Concord, the British are met by gathered minutemen

... who decimate the British troops

|

|

The convening of the Second Continental Congress (1775)

Following the events at Lexington and Concord, a Second Continental Congress gathered in Philadelphia in May of 1775 to prepare for what was clearly shaping up as a full-scale war between America and England. One of the Second Continental Congress's first acts (June) was to create officially a Continental Army and place George Washington in command of it (he was in New York, heading to Boston to take command, when the Battle of Bunker Hill took place; he arrived in Boston soon thereafter). Also, at Benedict Arnold's urging, the Congress authorized an assault on Canada to try to draw its colonial neighbors to the north into the war on the side of the American rebels. Thus it was that the Americans found themselves deeply involved in a war – a major war with a major European power. It was going to take a miracle to succeed. But these Americans believed in miracles. They counted on them. They knew what a deadly mission they had attached themselves to. It was virtually unthinkable for a common people to come up against their king. The king was armed with a mighty, well-experienced army, manned by battle-tested professionals. These colonial patriots would be offering as their own army only local farmers and tradesmen, not professional soldiers used to the discipline of extended military duty. History had no examples they could think of where a common people ever succeeded in throwing off the power of a major monarch. On the other hand, they had plenty of examples of popular rebellions, all of which ended with the rebels hanging by their necks on the gallows. From this moment forward these colonials would be considered under English law as traitors. And if this venture were to fail, they would all be hunted down and every one of them end up on the traitors' gallows. But they believed that they had a cause that demanded their lives in full commitment. Their America had been an experiment in government by the people themselves, an experiment ordained by God himself a century and a half earlier. They had answered that call, and God had proven himself faithful in this venture. Thus this was the sole ground on which they stood, with the understanding that this was after all God's war in which they were all merely foot soldiers themselves. God would see them through, for in God they trusted their destinies fully. |

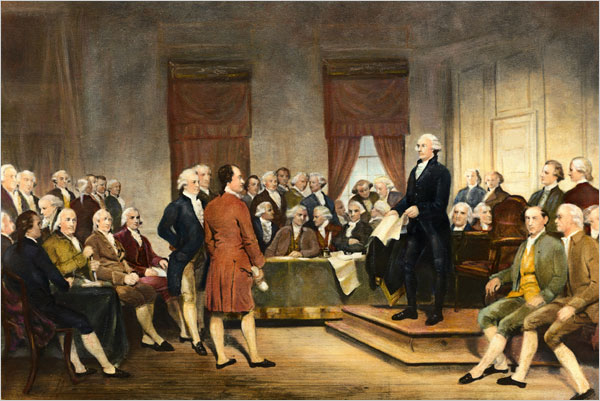

George Washington before the Second Continental Congress

Currier and Ives lithograph

The Congress had just appointed him commander-in-chief

of their Continental Army (June 1775)

Washington and the Second Continental Congress

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges