|

|

All-out battle at Breed's and Bunker Hill in Boston truly starts the war All-out battle at Breed's and Bunker Hill in Boston truly starts the war  The failed attempt to bring Canada in on the American side The failed attempt to bring Canada in on the American side The British are forced to vacate Boston – March 1776 The British are forced to vacate Boston – March 1776 The Declaration of Independence – July 1776 The Declaration of Independence – July 1776  The Articles of Confederation – November 1777 The Articles of Confederation – November 1777The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 116-122. |

|

|

The Battle of Bunker (and Breed's) Hill (June 17, 1775)

In response to this event, some 15,000 colonial militiamen soon gathered in the heights surrounding Boston. They were supplied by muskets and cannon seized in May from Fort Ticonderoga by American troops under Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold. With cannon in the hands of angry colonials dug into the heights surrounding Boston, the British in Boston now found themselves in a dangerous position. Thus in June an assault on the American positions on Breed's Hill and nearby Bunker Hill was ordered – to convince the colonial riffraff not to mess with the British Redcoats. However it took three British assaults on the American position on Breed's Hill to dislodge them, and the American withdrawal took place only after the colonials had run out of ammunition and only after they had inflicted huge casualties on their enemies: over 200 British killed and over 800 wounded, an unusually high percentage of these being British officers. The Americans lost less than half that number, and their retreat was orderly. The British claimed this as their victory. But it was for them a costly victory – one they could not afford to repeat. Furthermore, the Americans demonstrated that they would not be easily defeated. Subsequently the British attempted no such raid on any of the other American positions surrounding Boston.

|

Wilmington Society of Fine

Arts

The Death of General Warren

at the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed's Hill) – June 1775

by John Trumbull. The hill was taken by the British on the

3rd charge – after the

American powder had run out. British Major John Pitcairn

is carried away, mortally

wounded (right), and Dr. Joseph Warren lies

dying at the center.

Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

|

|

But things do not go well for the American Patriots

Spirits were running high among the Americans as their militias in those first days gave such an excellent account of their fighting abilities. But events would suddenly take the Americans in the opposite direction. It was as if the hand of God was showing them that while they were indeed true soldiers, without his help their efforts would avail them nothing. Disasters struck one after another, disasters which would test profoundly the character and spirit of the American officers and their troops.

Canada (1775-1776)

At first the Americans seemed unstoppable in their move on Canada. By the late autumn of 1775 Americans under Richard Montgomery had brought down the forts protecting Montreal. Then they captured Montreal itself. But soon events began to go wrong. Arnold was bringing up troops through New York, intending to link up with Montgomery against the city of Quebec. But hostile Indians, endless swamps and then early winter set in, slowing the movement and greatly weakening the ranks of Arnold's army. By the time the Americans had reached Quebec, the element of surprise was gone – and cold, hunger and disease wreaked havoc on Arnold's army. Arnold was a brave and daring leader. But it seemed as if God himself was dead set against American success in Canada. On the last day of December, a battle with the English at Quebec finally took place. The exhausted Americans were soundly defeated (and Montgomery killed). The survivors retreated a small distance from the city to wait for reinforcements (which never came) and warmer weather. In June of the following year (1776) a second attempt on Quebec was made – with no more success resulting than with the first effort. Another battle in October again brought failure, and Arnold retreated south back to Fort Ticonderoga, his ego greatly deflated. His valiant effort against incredible odds, human and natural, was well acknowledged at the time. But for Arnold it was still very disappointing. All that effort – and no victory to show for it. Because of this disappointing outcome, there would be no further effort to bring (or force) Canada into the war on the side of the rebels. |

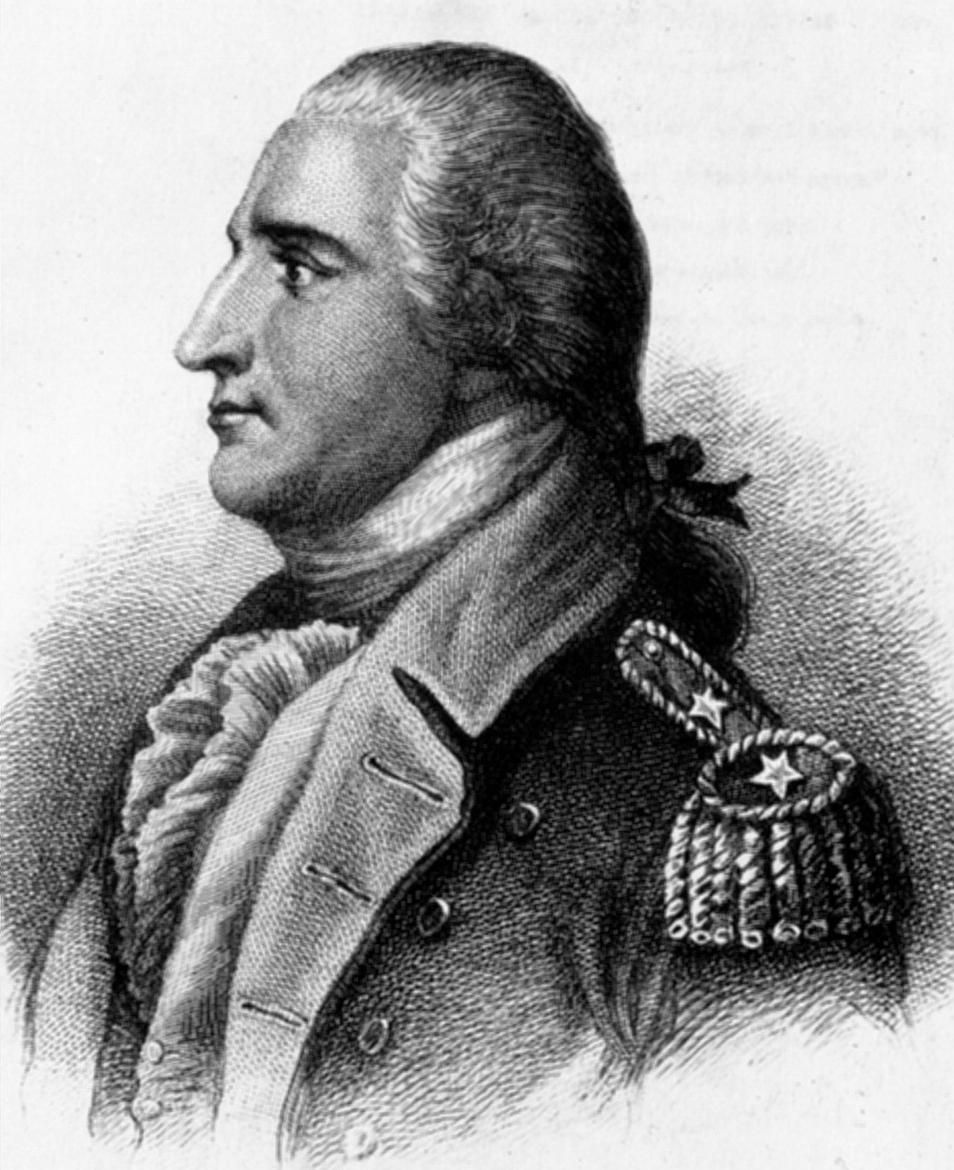

Copy of engraving by H.B.

Hall after John Trumbull, 1879

Knoedler Galleries

|

| While over the winter of 1775-1776 the British and American armies sat facing each other across the watery surrounds of Boston, in a most amazing feat, Henry Knox brought down sixty tons of canons and military supplies from Fort Ticonderoga (November 1775-February 1776) through huge snowstorms – to reinforce Washington's army which was running low on such supplies (but also most everything else). When the British in Boston saw Dorchester Heights newly reinforced by a whole new array of cannon, British commander Howe knew his position was very vulnerable. He decided on a massive assault (March 1776) on the American position, similar to the one at Breed's Hill. But oddly enough (!!!) a huge storm hit as his troops were about to embark, and the attack was called off. Subsequently Howe came to the decision that the British could not continue to hold Boston and finally they and the American Tories or Loyalists who had also gathered there vacated the city. They would not return to Boston during the rest of the war. |

Philadelphia Museum of

Art

His seizing supplies from Fort Ticonderoga boosted

both material and moral power among the Americans

Joseph Dixon Crucible

Company

|

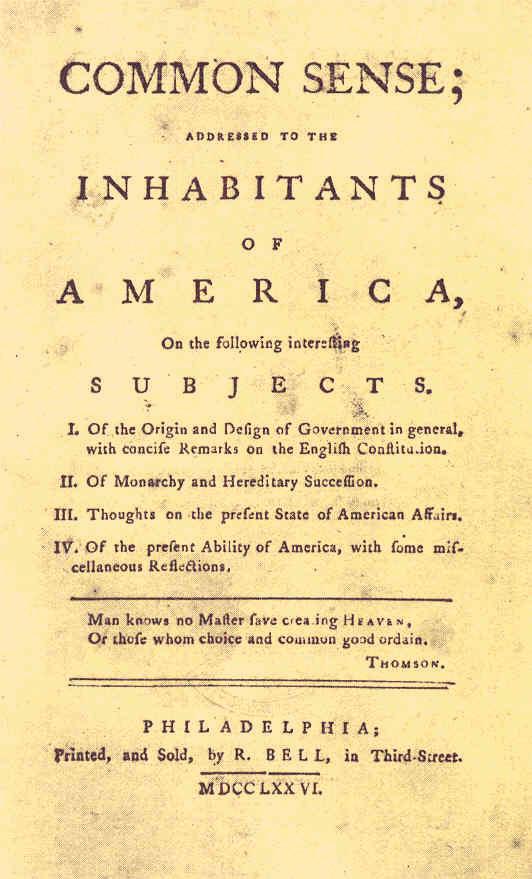

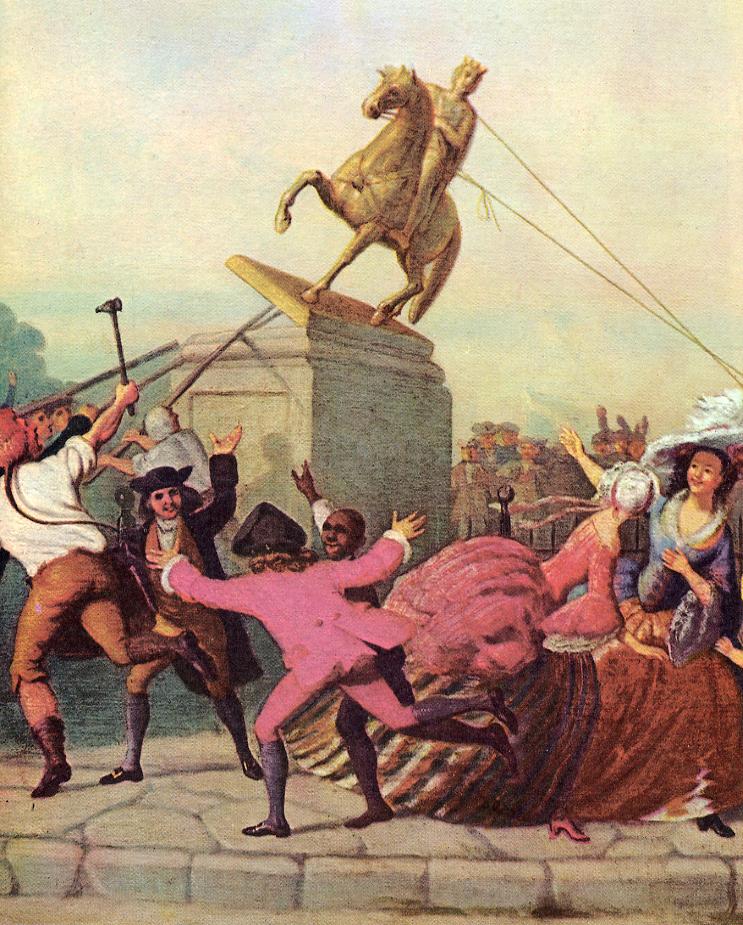

| American

spirits were not dampened. In early 1776, Thomas Paine wrote a

pamphlet, Common Sense, daring to speak the unspeakable: it was time

for Americans to separate from England and establish their own

government. In Paine's opinion, a republic was the best type of

government for America. The pamphlet was widely read and agreed with by

many. It was time to leave the British Empire.

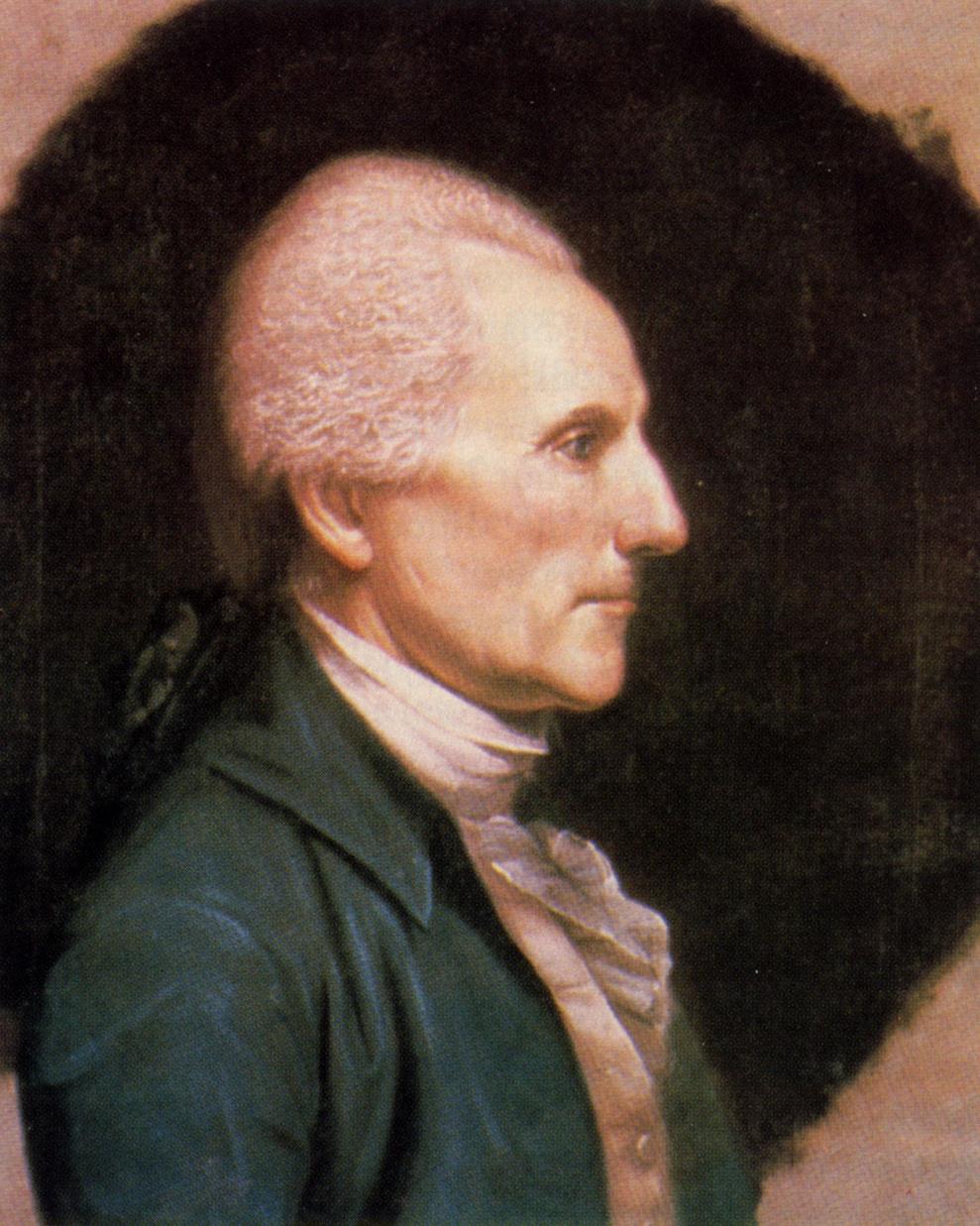

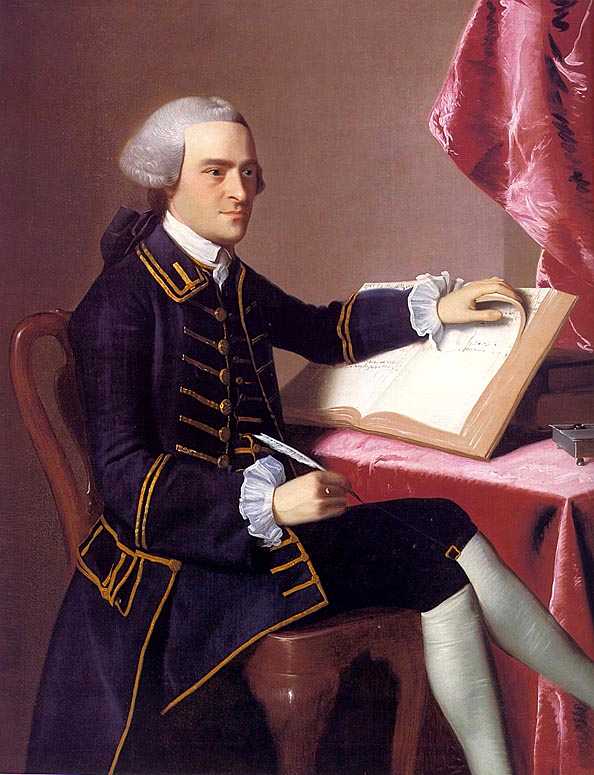

But such action would require the decision of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Yet none of the delegates had come to Philadelphia with this idea in mind or with any specific instructions on this matter from the colonial assemblies they were representing. They would have to return to their colonies and secure authorization. Of course this would be hotly contested by many who, though highly irritated at the high-handedness of the authorities in London, were yet quite unwilling to break the link with the Mother country. The debate in America in the spring of 1776 was intense, although clearly there was a growing momentum in the colonies in support of independence. Starting with North Carolina, one by one some of the colonial assemblies passed resolutions authorizing their delegates to vote for formal independence from England. But action stalled in the middle colonies. When in mid-May Congress took up a Declaration of Independence written by John Adams, four of the middle colonies voted against it. The Maryland delegation even walked out. But the independence momentum was gathering strength. On the same day that Congress passed the less than unanimous Adams declaration, the Virginia Assembly voted strongly for independence. Thus politically armed, the Virginia delegation arrived in Philadelphia in early June and submitted its own independence resolution for a vote: Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. The debate that followed was intense. But one by one – with the exception of New York, whose colonial assembly was sent scattering by the British occupation before the Assembly had a chance to vote – the colonial assemblies were instructed to vote for independence. Thus a committee of five was appointed to draft an explanation justifying the move to independence, to be submitted to the Continental Congress along with the resolution. Ultimately the task of drafting such a statement was given to the young, scholarly Virginia aristocrat, Thomas Jefferson. He put together a draft resolution (the language possibly borrowed heavily from Locke's Two Treatises on Government) and submitted it to the committee where it underwent changes,1 and then it was presented to the full Congress at the end of June. The famous Preamble states the case clearly: We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.When the Congress moved to a preliminary vote on the independence resolution on July 1st there was by no means unanimity in the Congress. Several states voted no. But nine voted yes, so the resolution was approved as ready for a final vote the next day, July 2nd. On that day a formal vote was taken, with Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Delaware finally lining up in support of independence. New York, still having no instructions from its assembly in exile, again abstained – but got instructions a week later to support independence. The document was put in its final edition on the 4th of July – and then (no one is sure exactly when) the delegates began adding their signatures to the document. Now the colonies were no longer just that. As they saw things, they were now thirteen free and independent states. 1Words

and sentences were revised, and about 1/4th of Jefferson's text was cut

out – including an assertion by Jefferson that slavery had been forced

on the colonies by Britain – causing Jefferson to be deeply irritated

by this editorial slighting of his personal creativity! Also the irony

in Jefferson's statement that all men are created equal was the fact

that he himself owned a number of slaves, who, though men, were

certainly not created equal or endowed with certain unalienable Rights. |

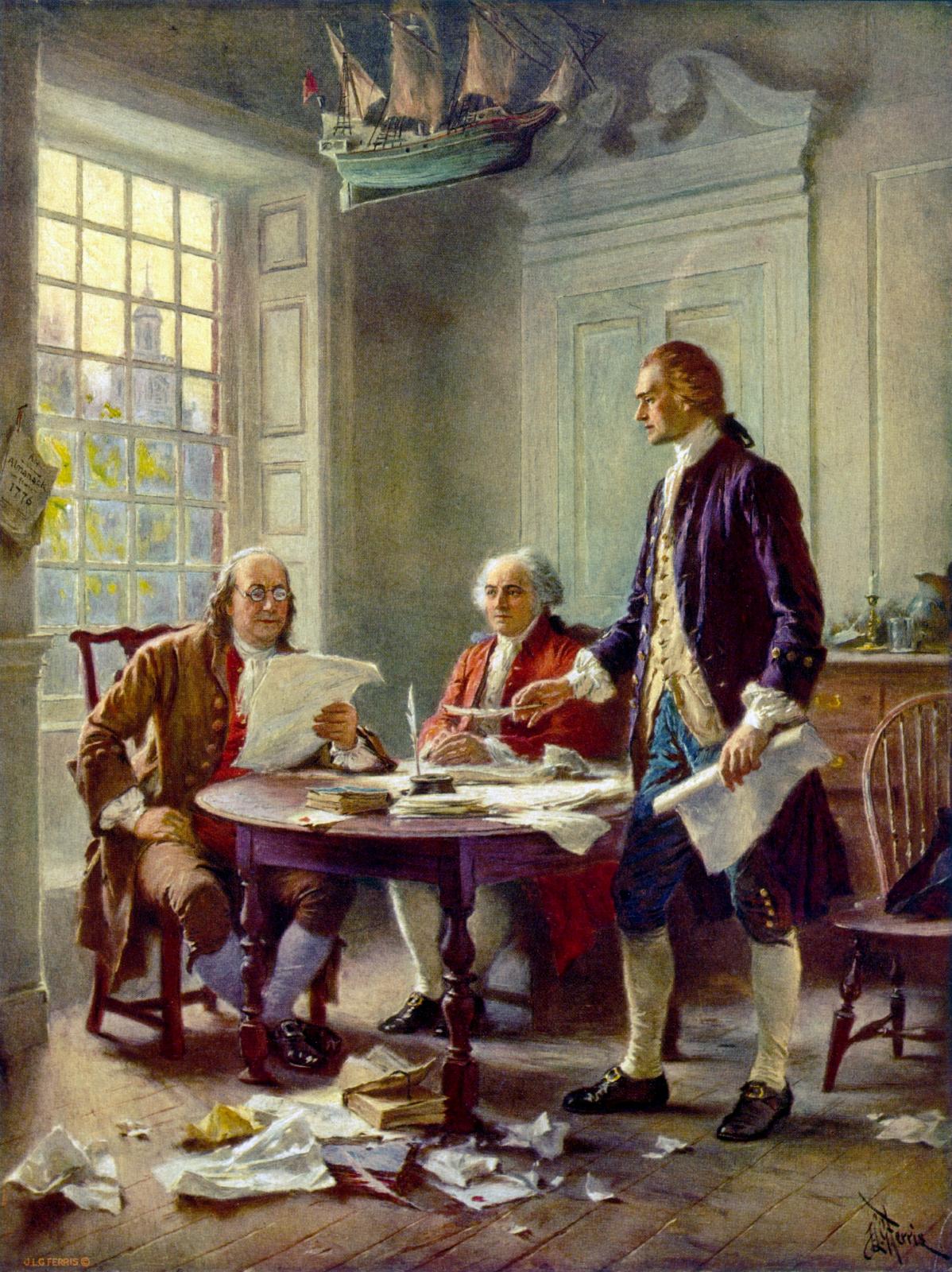

Library of Congress

Shelburne

Museum

(Franklin, Adams and

Jefferson)

by Jean Leon Gerome

Ferris

Virginia Historical

Society

Jefferson's draft copy of the Declaration of Independence – 1776

The Declaration of Independence (including its Amendments)

National Archives and Records

Administration

Architect of the Capitol

Historical Society of

Pennsylvania

Fort Ticonderoga

Museum

Collection of Gilbert

Darlington

|

|

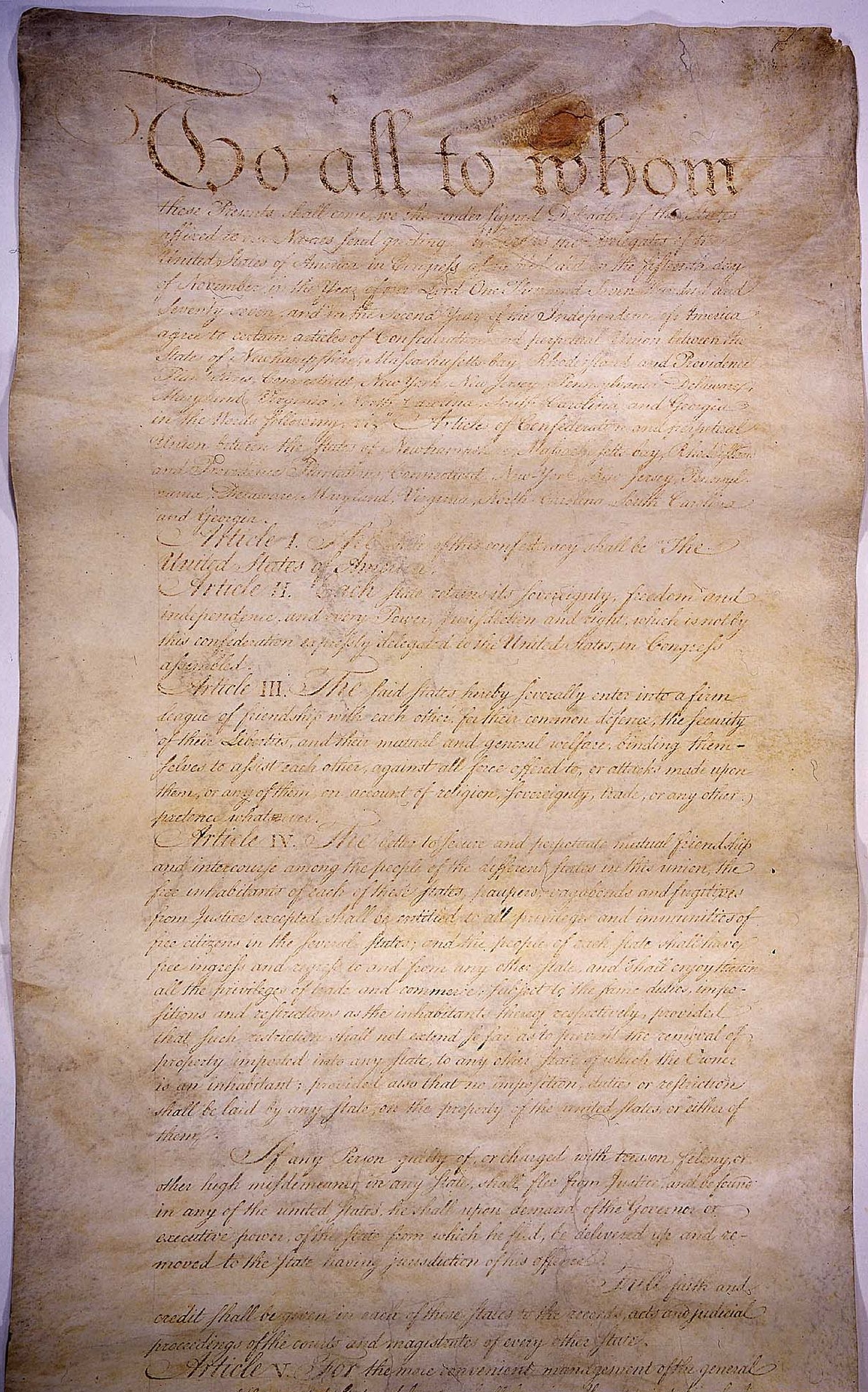

At the same time that the committee was appointed to draft a document

explaining America's Declaration of Independence, Congress appointed

another committee to draft a constitution for the government that would

oversee a union of the thirteen new states in the struggles that lay

ahead.

But unlike Jefferson's Declaration of Independence which was drawn up in very short order, work on this new constitution was very slow going. The draft for a confederation of the thirteen states was finally voted on by the Continental Congress in November of 1777 and sent as the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union to the states for ratification. But the ratification process was not completed until 1781. Nonetheless the political reality was that the new Confederation was fairly well understood to be operative from the moment that the final draft of the Articles was approved by Congress and sent to the individual states for ratification. The slowness of the process was not because of the newness of the idea of a written constitution for America. Although the English had a constitution which was largely unwritten but based on time-honored political traditions that all Englishmen understood well, the colonies had been written contractual affairs virtually from their founding. All had been founded in accordance with basic charters that explained in legal detail the purpose and operations of each of the colonies. These had been revised over the years. And in fact, with the declaration of independence of the thirteen colonies, each of them became busied in writing new constitutions outlining their respective structures and functions as independent states. The problems involved in setting up the Confederation were largely political – most frequently disagreements over border questions. Now that they were independent, each state began to look to its own future, its growth, its expansion. And this frequently brought them into conflict with each other over the question of state title to the western lands. Nonetheless the states did need to work together. So even if they had not formally signed on to the Articles of Confederation, they operated pretty much as if it were in full effect. Thus the Continental Congress really saw itself early on as the legislative branch of the confederacy, fully ratified or not. |

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges