|

|

Yorktown – 1781 Yorktown – 1781  The British officially capitulate – 1783 The British officially capitulate – 1783 The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 137-138. |

|

|

The siege of Yorktown (September-October 1781)

and the effective end of the war Then Cornwallis turned his eyes north to Virginia, reasoning that if he did not succeed in breaking Virginia's resistance, he would not be able to solidify his hold over the South. In the meantime, turncoat Benedict Arnold was leading British and Tory troops on destructive raids on the northern Virginia countryside, targeting particularly the plantations and farms of the Patriots (or rebels, depending on how you looked at matters) which Arnold's Tory troops were pleased to burn to the ground. In May (1781) Arnold and Cornwallis joined forces in central Virginia. Then in June, Cornwallis began to head eastward toward the Virginia coast, to Yorktown, located along the wide and deep York River. His plans were to dig in there with his army while awaiting reinforcements and supplies to be brought in by ship by way of the Chesapeake Bay. In early August Washington abandoned his plan to attempt to seize New York City with his combined French (led by General Rochambeau) and Patriot forces – and instead decided to head south to Virginia to link up with French General Lafayette (who had been shadowing Arnold and Cornwallis) and even more importantly, to link up also with a huge French naval fleet under Admiral de Grasse heading north from the Caribbean to the Chesapeake Bay. Washington and Rochambeau's move South was miraculously kept hidden from Clinton, who kept his army in New York, believing that this was where Washington was planning to attack. De Grasse's fleet arrived at the Chesapeake and in early September defeated not only the British fleet stationed there but also another fleet subsequently sent from New York by Clinton to break the French position. British failure left Cornwallis stranded at Yorktown, now surrounded on land by American and French forces and on sea by the French fleet. The bombardment of Cornwallis's position became relentless and Cornwallis was now running out of food and supplies. Finally, in mid-October, with the Americans1 and French able to break through his last line of defense, Cornwallis surrendered himself and his army of 8,000 men. Several days later a relief fleet of 7,000 British troops arrived at the Chesapeake. But hearing of Cornwallis's surrender, and realizing the hopelessness of trying to send an army ashore to a position strongly held by American and French troops, the fleet turned back to New York City. No more major actions were to take place after Yorktown. As British Prime Minister Frederick Lord North exclaimed upon hearing the news back in England of Cornwallis's surrender, "Oh God, it's all over." The war was indeed all over. 1The

final American assault on the last of the British redoubts (forts) was

led by Washington's young staff officer, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton

and Washington had already grown very close as political associates and

personal friends. |

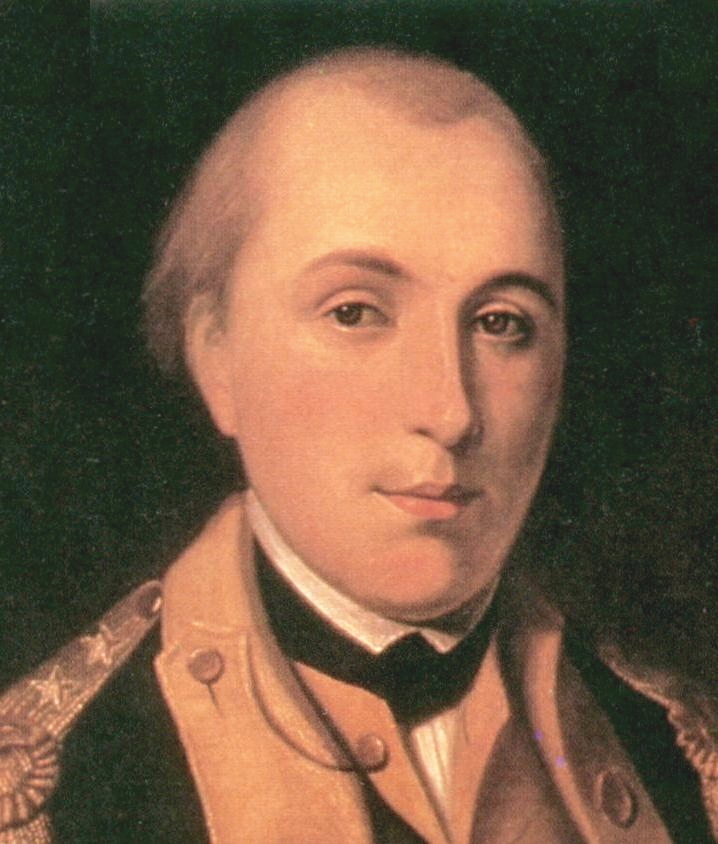

French General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Rochambeau

allied closely with Washington in the assault on Cornwallis at Yorktown

French Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse,

whose French fleet twice defeated British fleets in the Chesapeake

thereby leaving Cornwallis and his troop isolated at Yorktown

to lead the American troops in final assault on the British at Yorktown

October 14, 1781

Virginia State

Capitol

The British surrendering to French and American forces at Yorktown

(October 19, 1781)

by John Trumbull (1820)

(Cornwalis was actually

not himself present at the surrender)

Rotunda of the US

Capitol

|

|

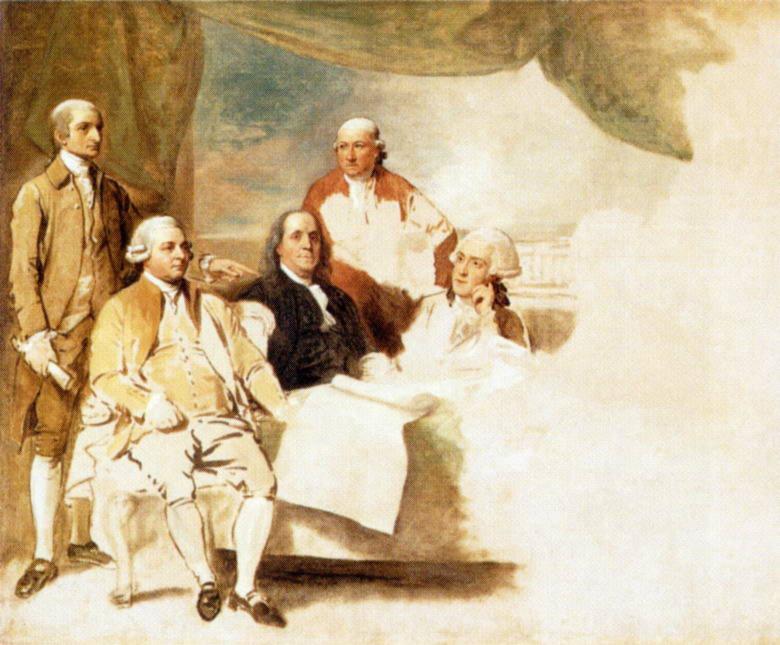

The Treaty of Paris (1783)

Negotiations formally ending the war got underway in Paris in April of 1782. Representing the victorious former colonies, since 1776 calling themselves the "United States," was a delegation led by Ben Franklin, John Adams and John Jay. The Treaty of Paris, drafted in November of that year, was not formally signed in Paris until September 3, 1783. It was then ratified by the Congress of the Confederation of the United States on January 14, 1784 and by King George III on April 9, 1784 – finally granting formal recognition by the British of the full independence of the thirteen former colonial States. Terms of the treaty included the return of Loyalist property seized during the war (never really honored), British financial compensation to Americans who lost their slaves when the British freed them (also not ever honored), and recognition of the boundaries of the new United States (rather vaguely defined, and later a point of serious contention). The war was officially over. And a new republic - and the early stages of a new nation – was now about to take its place in history. |

The Treaty of Paris – September 3,

1783

unfinished picture by Benjamin

West

(the British refused to

sit for the picture)

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges