|

|

The original intentions of the designers or "Framers" of our Constitution The original intentions of the designers or "Framers" of our Constitution The "machinery" of government-by-law is finalized The "machinery" of government-by-law is finalizedThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation 2021, Volume One, pages 139-146. |

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

|

The machinery of government

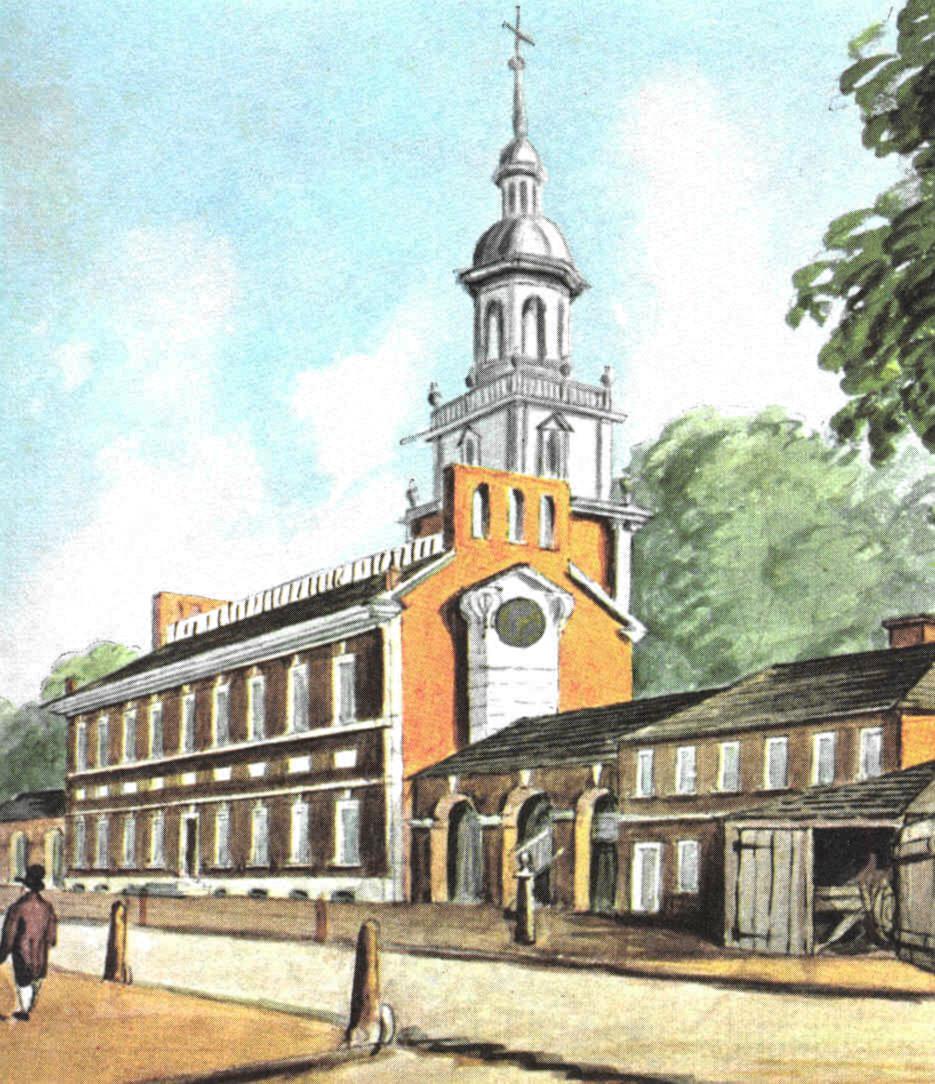

A Republic ... if you can keep it (Benjamin Franklin's reported response to a question asked of him as the delegates were leaving Independence Hall, having finalized the draft of a new American Constitution in 1787) It is generally understood today that the term "American government" applies to some kind of self-standing institution, also referred to as the "state,"1 assigned the powers to guide or direct Americans toward particular political goals. Supposedly this institution, the government or state, functions according to a set of basic operational rules (the Constitution and its many legal spinoffs) which empower and guide, but also restrict, the state in its operations. In a typical class on American government it is this institution and its operations that come under study. Quite in line with the Enlightenment's understanding of the dynamics of life, the American government is treated as if it were some kind of great machine (thus the talk of the "machinery of government") that operates rather mechanically in providing guidance for the country. The structure and function of each of the various parts of the governmental machine are brought under careful study: Congress, the presidency, the courts, the bureaucracy, the political parties, the elections that fill the various positions or offices that run this government. The goal is to bring into focus the end products or policies and programs that this governmental machinery produces in order to make a better America: road-building programs, assistance to farmers, the regulation of the value of the nation's currency, the policing of criminals, the collection of taxes to run the government, the defense of the nation's borders, etc. This approach to the study of governmental mechanics is considered to be political science. Universities even offer a special degree to those who take up the advanced study of how such a governmental institution should be managed: the master's degree in public administration (the MPA). It's all very logical, all very mechanical, and ideally all very manageable from the heights of political power. However, this study takes a very different approach to the idea of government and its mechanics. What this study is founded on is the central idea that government is that which governs (of course!). And what governs a society is largely the inner core of a people's sense of purpose, their sense of right and wrong, their sense of why it is important to work together as a people. A public institution such as the state is helpful to a people in symbolizing or clarifying these rather intangible intellectual, moral and spiritual ideas which govern their thoughts and actions. It is there also to set boundaries on human behavior when such moral discipline finds itself lacking in the hearts of certain individuals, or even whole communities. But ultimately no mechanical institutions of state that govern the common folk from above can take the place of what the people, by their own training, habit, inclinations or loyalties can do on their own. For truly that which governs best is that which governs the hearts of a people. Moving forward on the basis of long-established political habits

It is important to note why this author does not follow the general trend of referring to the war they had just gone through as the "Revolutionary War" – but instead always refers to it as the "War of Independence." America itself did not change in character. In that all-important way America itself underwent no "revolution." It simply fought to preserve the very political and social character that had been long-established in America, a political-social quality that Americans refused to give up to George III. Certainly independence was achieved in this very bloody struggle. But nothing "revolutionary" happened to the way America went about its usual social business as a result of the war! It was simply moving forward on the basis of long-established political habits. Nor did the Americans newly invent Constitutional government ... all the colonies having been run according to very precise legal principles outlined in their founding charters laid out a century and a half earlier (but updated as the need arose). They planned to continue as independent "states" in exactly the same manner. Thus upon their move to independence in 1776, each of the colonies had worked quickly to draft up new charters or state constitutions. In short, such self-government was by no means a "revolutionary" development for Americans. They were well-practiced in self-government according to well-established legal principles. The original intentions of the designers

or "Framers" of the American Constitution Furthermore, because of the tendency today of Americans to view their government as a set of mechanically operating public institutions governing the country from Washington, D.C., it is difficult to understand exactly the dynamic which directed the thoughts and actions of the Constitutional Framers back in 1787, as they attempted to put together a new political union. What today is widely understood as government was not at all what they were attempting to put together. What they were aiming for certainly was designed to be much stronger than the Confederation, the system under which the newly independent thirteen American states had at first been attempting to work together – but not succeeding very well in the effort since the end of their war against England in 1783. Was this new thing simply a treaty of alliance among thirteen newly independent states? Was it creating a new government? Did it in fact set up a new national state to preside over the affairs of the thirteen newly independent states and their people? What exactly was it? The Framers termed it a republic. We today think more in terms of the Framers having created a democracy. They saw it as a federal union or alliance of thirteen independent states. We see it today as the foundation for a federal state governing from Washington, D.C. They could not see exactly what it might eventually become. We today have difficulty in seeing what it was and what these wise Framers originally intended it to be. Certainly the last thing the Framers wanted to do was to create an all-dominant state. They had just gone through a long and brutal revolt against exactly that sort of institution: the monarchy of England. At that time, European kings or monarchs viewed all things within their royal estate – all lands, and all people and buildings on these lands – as being their property, belonging to their estate, and therefore under their complete dominion. People lived on their land or estate purely at the tolerance of the king, or so the kings claimed anyway. If you did not like this arrangement you could leave, presuming there was anywhere else to go, the dangerous wilderness of America being about the only possibility at the time. The Framers were very sensitive about the dangers of tyranny coming from a strong central state. This concern was clearly laid out in their Declaration of Independence of 1776, which outlined one after another the many tyrannies that had developed of late under the English royal or monarchical state. Subsequently many young men had died in the effort to preserve the freedom of life in America against such tyranny. And the leaders of this revolt, which included many of those same men gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 to draft a new constitution, had put on their heads the price of treason. They all would have been executed by the English authorities if their revolt had failed. They had so recently risked so much to preserve American liberties. Thus they were not in a mood to give those same liberties away to an American version of the English state that they had just succeeded in getting the country out from under. And yet they stood in grave danger of disunion and – if their new United States remained nothing more than a loose collection of very small, rather weak states – becoming easy prey for imperially ambitious European kings. England might return in an attempt to recapture these states. Even France or Spain might attempt something of the same nature if these thirteen newly independent states did not come up with some kind of stronger political union than this very weak confederacy they had been trying to operate under. A revision or replacement of the inadequate Confederation?

Thus they gathered in Philadelphia in the late spring of 1787 under Washington's rather silent leadership (a gathering which would take them into September to complete their work) to come up with a plan that would allow the various states (Virginia, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Georgia, etc.) to work together more closely ... and give their new political system more muscle to handle unexpected domestic problems as well. The original thought was simply to revise the Articles of Confederation by strengthening the Continental Congress in its various legislative or law-making powers. ut as they approached the scheduled gathering, a number of the delegates already realized that they needed to create an entirely new institution, one with enough authority to help them work together in some kind of closer harmony, yet with no more authority than absolutely necessary to fulfill that task. Since the beginning of the revolt in the mid-1770s they had worked together as thirteen former colonies, now thirteen independent states, under some kind of sense of alliance. They had coordinated their revolt in accordance with the Articles of Confederation, which served as their first joint constitution (put together in 1776-1777 and finally fully ratified in 1781). The Articles and the Confederation had served them fairly well (though by no means perfectly) during the heat of battle against the English armies, supporting Washington's army (sometimes barely so!) and keeping them together in one mind and spirit during the dark days of the revolt. Yet now that this danger had passed, they faced a new danger of splitting apart into a number of contending mini-states. Indeed, the thirteen states had recently begun to actually compete against each other politically and economically. They were putting up trade barriers to prevent the sale in their own states of the products of the other American states, in order to protect the production of their own farmers and manufacturers. They were even beginning to send out their own diplomats to work separate commercial deals with foreign powers (such as France, Spain and even England) in competition with each other. If they did not cease this competitive selfishness, they would soon find themselves not only deeply divided but also easily conquered. In a condition of weakened disunity, they would most certainly provoke the lusts of power-hungry monarchs to return to America in a power grab designed to absorb these small, vulnerable states into their ever-expanding empires. Yes, there was a treaty by which the English government had formally recognized the independence of the former American colonies, now fully sovereign states. But also remember that to European monarchs those treaties had no enduring value. They were quickly broken by ambitious kings when any new opportunity to gain additional territory or regain formerly lost territory presented itself. These American Patriots did not want their political divisions to offer those monarchs just that opportunity. They needed to come together in a union that would protect the sovereignty of all these new American states. They needed truly to be the United States of America. 1The English word "state" comes from the French word tat, which in French means both "estate" and "state." The king's property or estate was the heart of the typical European "state." |

|

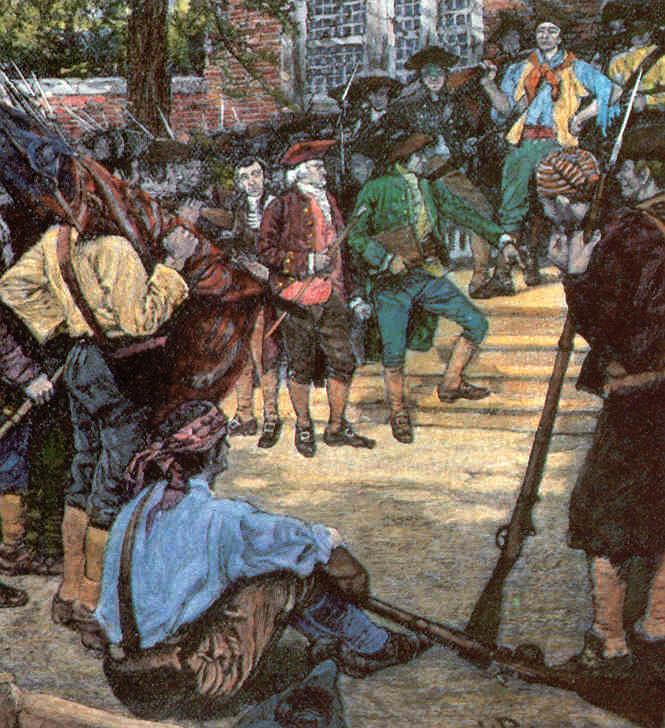

Shays' Rebellion (1786-1787) in Western Massachusetts

Also an incident following the end of the War of Independence had put another type of scare on the political leaders of the newly independent states, leaders who came mostly from the ranks of the Southern landed gentry and the New England and Middle States upper middle class of lawyers, bankers, and merchants. This incident was reminiscent of Bacon's rebellion in Virginia a century earlier, and had the same unnerving effect on these gentlemen: they knew that they had to act decisively or face catastrophic domestic political disorder, a danger at home as great as the one posed by the power-hungry European monarchs abroad. After the war a number of soldiers, who had received little or no pay for their years of service in the Continental Army, returned to their homes in rural Western Massachusetts, only to find that in their absence they had accumulated an unpayable debt on their land for taxes owed the local and state governments as well as unpaid mortgages owed to the merchants of the Eastern seaboard cities (such as Boston). Hard currency was scarce, a deep economic recession had set in upon America at this time, and there simply was no way for these farmer-soldiers to meet these debts. Appeals to the local and state authorities to help them out fell on deaf ears. They requested the opportunity to repay their debts in agricultural goods rather than in the scarce hard currency demanded by their upper-middle-class creditors in the East. But their nervous Eastern Massachusetts creditors insisted on repayment in full, in hard currency. Falling into bankruptcy, the farmers' lands were seized by the local courts for auction to cover the full amount of these obligations. The farmer-soldiers were outraged at their treatment, and rebellions (one of them led by Daniel Shays, whose name was assigned to the broader event) broke out in a number of places in Central and Western Massachusetts. It finally took the violent confrontation by the Massachusetts militia in February of 1987 to break the spirit of the rebellion, and further inspire American leaders to look to the need to meet to consider a much stronger revised or even new political union. Thus this near run-away event was clearly much on the delegates' minds as they arrived in Philadelphia in May to begin their work. They obviously needed some kind of system to bring social order to their new America, or if not attacked from abroad by foreign powers they would be shattered from within by disenchanted social classes of Americans Strength and unity without tyranny

Thus those who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 knew they needed a strong central bond in order to keep themselves fully united, as they had been in the years of the war. But at the same time this bond must not be so powerful as to compromise the powers of the individual states – which they believed were the better preservers of the liberties of the people. Indeed, they needed an idea, a political ideal, that could continue to command the loyalties of all Americans, a governing system with enough power – but not too much power – assigned to a uniting central authority. This required a delicate balancing act which they would have to perform in order to succeed in this enterprise. |

| In 399 BC, The Sophists convinced the Athenian democratic Assembly to vote for the death of Socrates. The Sophists were deeply annoyed at Socrates's constant criticisms about how the Sophists cleverly influenced the thinking of the Athenian citizenry ... leading the people to make very foolish – even self-destructive – decisions (like the decision itself to kill Athen's wisest man himself!). |

|

Failed historical precedents

But they had no very successful precedents in history that they could model their new system of government after. They were all well-educated men and quite aware, through their considerable knowledge of both Biblical and classical history, of the lack of long-term success of Ancient Israel, the ancient Athenian Democracy and the ancient Roman Republic, political systems which came closest in form to what they sought to build in America. Sadly, all systems had failed to maintain their original purposes as governments. Athens as a democracy had been directly run by the citizens of Athens – much as the local communities in the American colonies had been run for the past 150 years. But the Athenian citizens had been easily manipulated by clever politicians (the Sophists or wise men) so as to turn Athens itself into a tyrannical state dominating and exploiting its neighboring city-states, leading to a violent rebellion among those Greek city-states. This produced the ruinous Greek civil war known as the Peloponnesian War – and ultimately the political destruction of Athens itself. Thus the Philadelphia delegates understood clearly that even a democracy, poorly led, could turn itself into a popular tyranny which would inevitably self-destruct.2 As for Rome, the delegates remembered that Rome started off quite well as a republic. The idea of Roman government as a republic was that it was intended to be a government of carefully designed and quite fixed and permanent fundamental laws, and not just the result of the changing and usually foolish ambitions of particular men, whether a few powerful figures, or the many, as in tribal societies such as existed everywhere in Italy in the formative days of the Roman city-state. A governing system of laws favored no particular class, ethnic group or even individuals, and allowed the Romans to expand the domain of Rome as neighboring societies were brought under submission – but whose people of these neighboring societies were then invited by the Romans to become part of the Roman Republic itself as its newest citizens under the law. This proved to be a generous and very successful strategy for building and expanding the Republic. At first, the Republic served Roman popular interests well. Rome was too big to be ruled directly by the people as in the early Athenian democracy. So the people elected representatives to rule on their behalf. The system still belonged to the people but was administered by their elected representatives, much like the American colonies had been governed at the highest level of authority in each of their individual colonies. In fact most of the Framers of the Constitution had a republic in mind as they set out to redesign an American political system. But sadly, in the long run, the Roman Republic failed to continue to respect Rome's legal ideals, and ultimately therefore failed to represent all the people as well, despite repeated attempts to perfect the system through the implementing of various new constitutions. The Republic eventually became merely the tool of the more wealthy and powerful patrician members of society. Revolts against this tendency of the Roman Republic toward oligarchy (rule by the favored few) were frequent and brutal on the part of the increasingly impoverished and consequently very angry common people (the plebeians). The military chose to intervene more and more in the name of the plebeians to bring peace to Rome. Finally, the military legions led by the Caesars took permanent control of the Roman government. Thus the Roman Republic gradually transformed itself into an imperium, a military state or empire ruled by the imperators (emperors) or commanders of the Roman army, who would govern for the people (no longer by the people). Tragically, the Republic had failed to maintain itself because of its inability to stay socially self-disciplined by the fundamentals of Roman law, and thus therefore by the traditional political restraints on power politics – even politics conducted supposedly on behalf of the people. Popular government (government by the people) ... could this turn into a democratic tyranny as in ancient Athens? Or could an American republic preserve itself against the growth of bitterly contending special interests (as in Western Massachusetts farmers versus the Eastern seaboard financiers) – and the tendency of men to call on the force of arms to decide political outcomes even within a peaceful society as in ancient Rome (also as in Western Massachusetts!)? Nothing was very promising about the historical record left behind by Athens and Rome. They had meant well, had started out satisfactorily enough, but had failed to maintain their original political – or moral – course and eventually turned themselves into tyrannies, and thus declined and died. 2The

Greek philosopher Aristotle was cool on the idea of democracy, or any

particular form of government, whether by one, a few or the many. To

Aristotle it was not the form of government but the morality of the

people and their leaders that distinguished good government from bad

government. Aristotle's famous teacher Plato was even harder on the

idea of democracy, seeing how easily the democratic masses were led to

call for the death of Plato's great teacher Socrates. The Framers of

the Constitution were well aware of the opinions of both Plato and

Aristotle. |

|

Historical Society of

Pennsylvania

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges