|

|

The strong Chrisitan component in the discussions The strong Chrisitan component in the discussions  Ben Franklin's reminder Ben Franklin's reminder The Framer's Christian take on the issue The Framer's Christian take on the issue Comparing the American and French efforts at Republic-building Comparing the American and French efforts at Republic-building The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 146-156. |

|

|

|

|

The Framers understood the dangers of building only on

ever-changing human logic ... rather than on permanently-established basic law Franklin's appeal registered itself as strongly as it did because all present knew well the Biblical story of the Fall of Adam and Eve from God's Paradise. Adam and Eve had ignored God's warning not to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (human logic), but instead had followed the Serpent's advice to do exactly that because it would make them be "like God." The temptation to play God by assuming for themselves the knowledge of Good and Evil was too great for Adam and Eve to resist. But in breaking that command, disaster struck. What they got for their efforts was only a half-truth (the most dangerous of all lies). Apart from the fundamental guidance of God, their logic could not guide them except in merely self-justifying circles. It did not produce true knowledge. Their logic was only technique – not Truth itself. Truth came from a deeper source of life – from a depth that human logic itself could never reach. Only a close, fully trusting relationship with the Author of Life – and Life's basic Truths as God ordained them – offered true knowledge. But by their disobedience, by their questing for knowledge apart from God, Adam and Eve had ruptured that vital relationship. They were on their own with their own sophistication (as in the sophistication of the Sophists of Ancient Athens). But this sophistication only made them all the more aware of life's shortcomings, especially in others, whom they blamed for their problems. Ultimately this broken relationship with God ended in death – their death. Not a pretty picture! The Framers understood very well the moral of that story: human logic was not the answer to life's challenges. Relationship, holding together in a spirit of unity, and holding to God as the ultimate judge and ruler of life, was the path they needed to follow. The better way would come if they were willing to submit their particular self-interests, and the moral and tactical logic man used in defense of those self-interests, in support of the greater bond that held them together as Americans – Americans under God. What they ultimately formulated as their new American government was a rather simple alliance system that encouraged them to work together without according too many powers to the system itself. This new federal system was their response to the challenge. Even then they knew that this new system would work only if man's hunger for power (as in Adam and Eve's desire to play God) was held in check. A deep respect for – and even fear of – God among the people was the only way they felt that things might stay on course as they faced the many challenges ahead of them. This was a component missing in the logical systems of the philosophers, ancient and modern. It was not missing in the thinking of the Framers of the Constitution. In fact it held a central or foundational place in their understanding of things.

|

|

|

Contrast the American approach to self-government in 1787 with the

French Revolution which broke out two years later in 1789 – just as the

American Constitution went into effect.

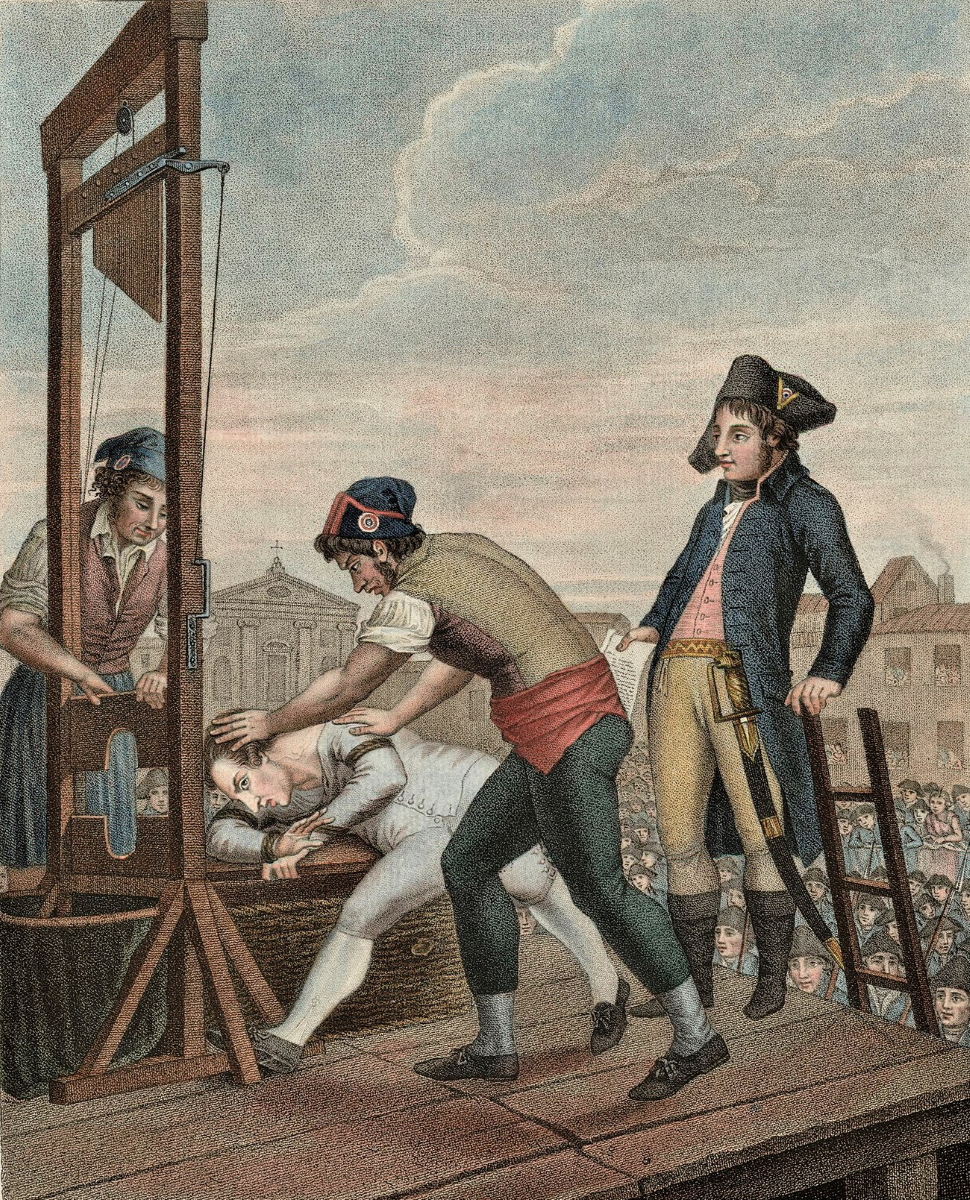

The French were led simply by their belief in the power of human reason or logic – especially their own logic (that is, the logic of their political leaders) – which they supposed would produce a Platonically perfect French Republic. Tragically, the leaders of the French Revolution had only bright ideas – and no practical or deeply tested experience in guiding and directing a society. Nor did the French people themselves have any understanding of what their role was to be in this new Revolutionary society. God played no part in the plans of the French reformers. Indeed, their mood was generally hostile to the idea of God (whom they frequently mocked), for they understood liberty as freedom from religion. They viewed religion, the Christian faith in particular, as a key component of the very Old Order that they were bent on overthrowing. They were determined to be ruled not by God but by man – by man's basic ability to do the right thing, the logical thing. By way of complete contrast, the Framers were well aware of the dangers of trusting to merely self-justifying Human Reason to direct them. They were quite aware that God – whose rules for human behavior were as eternal as the laws of physics and chemistry – had to stay sovereign over these United States, or they too would drift down the "creative" or "progressive" path of Human Reason that the French Revolutionaries had foolishly taken up. Totally unsurprisingly to the more pragmatic Americans, when the French intellectuals attempted to put their "enlightened" political philosophy to practice – they found themselves unable to agree among themselves as to what exactly constituted the right thing, the reasonable, or logical thing. One man's logic was not another man's logic. Soon they fell from their Idealism into mutually hostile intellectual camps. Consequently, the Revolution quickly collapsed into a murderous chaos. At first they kept the guillotine busy beheading the old ruling class of the Ancien Régime: France's king and queen, its barons and aristocrats, its bishops and clergy, etc. But having overthrown the Old Order ... they could not agree on what the New Order should look like. It was at this point that the leading revolutionary groups, the Girondins and Jacobins, savagely turned on each other over points of differences in their "pure" thinking ... sending each other to the guillotine! And thus France fell into a very bloody period, especially during the years 1793-1794, a period known today as the French "Reign of Terror." And so it was that the French "enlightened ones" themselves became the victims of their own Revolution.

It finally took the dictatorship of Napoleon (1799-1815) to bring the French under some kind of political order. It required a new form of tyranny to rescue them from the tyranny of unrestrained human self-interest – and the reason or logic used to justify such self-interest. So much for human Reason and the Idealistic belief that man's Reason opened the way to some kind of absolute Truth and Goodness! Yet it would be a sophisticated belief that would never seem to die, despite the ugly historical record of man's continuing attempts to build utopias on the basis of human Reason alone. By way of strong contrast, the Framers of the Constitution were very aware of such potential dangers.1 Thus the American "Revolution" they presided over, highly suspicious of unrestrained human behavior and thus cautiously minimalist in its utopian efforts, succeeded awesomely in creating a viable republic – one loaded with many checks and balances in its distribution of various governmental powers. And thus it was that the American constitution-building effort would succeed brilliantly ... to the same extent that the French Revolution failed miserably. 1Except

probably Jefferson, who anyway was away during the drafting of the new

Constitution, serving as America's Minister (Ambassador) to France

(1785–1789). In Paris, he was wholly enraptured by the reformist spirit

of the French philosophes (intellectuals or philosophers), a spirit

which was clearly driving France toward revolution. Jefferson, being

himself a utopian idealist, long remained a devout defender of the

French Revolution, which finally broke out in 1789 (just before he

returned to America). Indeed, he was one of the last to finally admit

that the murderous Reign of Terror into which France soon fell had

tragically betrayed the original high ideals of the French utopian

philosophers he once so greatly admired. |

The execution of French King Louis XVI – January 21, 1793

... setting off a realm of mass executions ... first of the French nobility and clergy

then descending down into mutual slaughter of opposing revolutionary groups,

Jacobins vs. Girondins

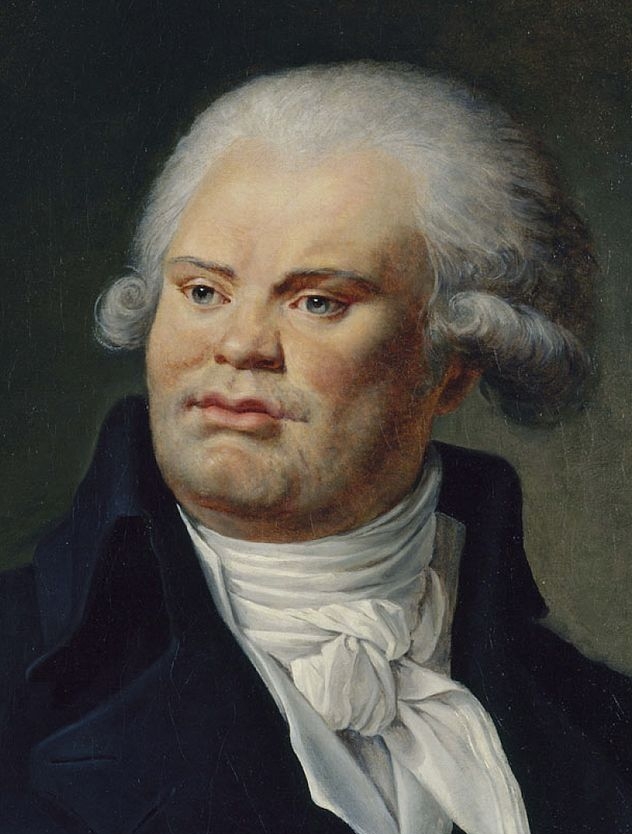

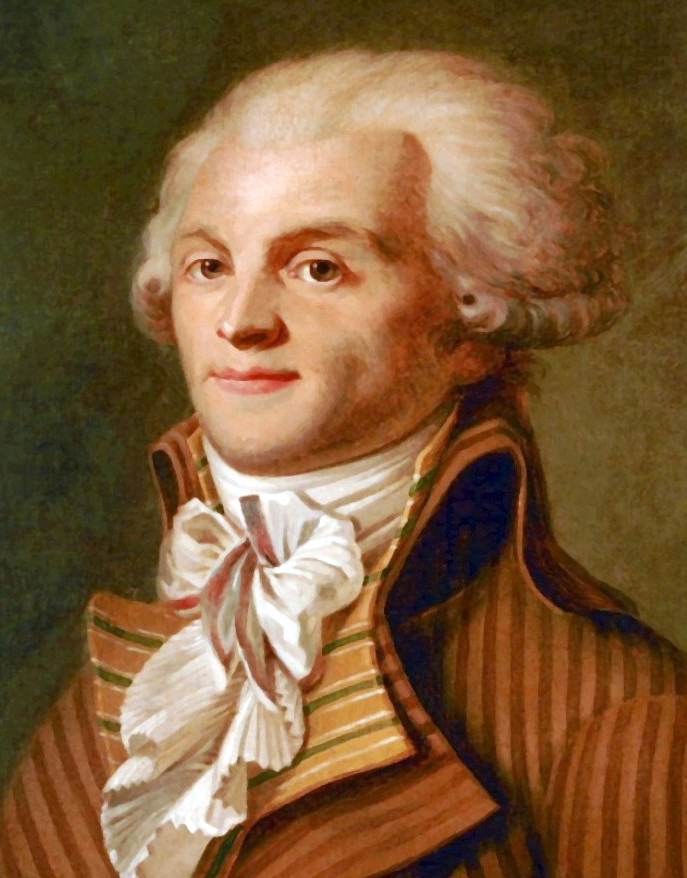

Leaders of the French Revolution

Georges-Jacques Danton early leader ...

replaced by the more radical Maximilien Robespierre

The sociopath Jean-Paul Marat ...

who used to make the list of those to be guillotined during the Reign of Terror

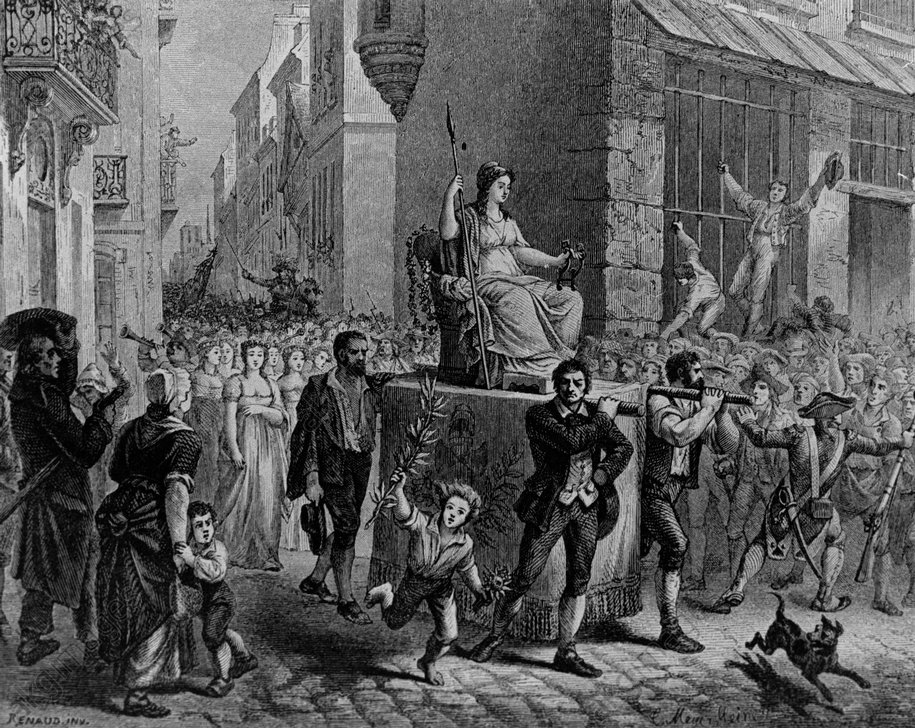

The Goddess of Reason, symbol of the new Cult of Reason (1793)

replacing France's traditional Catholicism. She is being led to the Cathedral Notre Dame

where she will be placed at its altar as a sign of the new Age of Reason ...

ironically at the same time that the French are slaughtering each other over points of "reason."

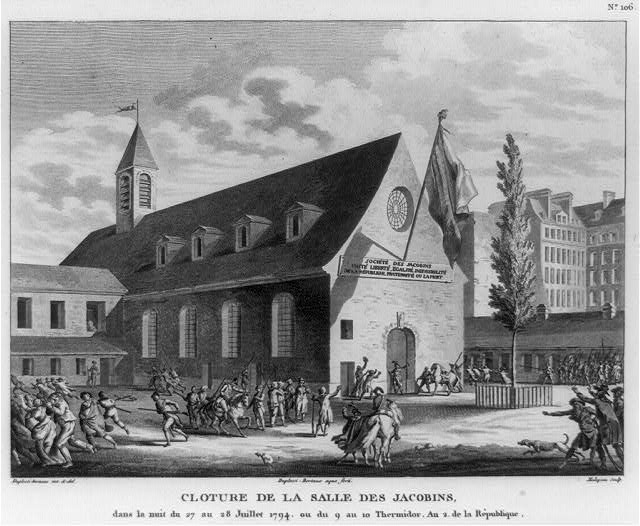

Jacobin headquarters during the height of the "Reign of Terror" (July 1794)

The mass-murderer Robespierre himself is finally guillotined (July 28, 1794)

... the beginning of the slowdown of the Reign of Terror

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (reigned 1799-1815) finally settles France down

... before spinning the country outward in a campaign of European conquest

Miles H. Hodges

Miles H. Hodges