|

|

America is slowly drawn into the French-English Napoleonic Wars America is slowly drawn into the French-English Napoleonic Wars  James Madison James Madison  Steps towards war with the British (June 1812) Steps towards war with the British (June 1812)  The first round of the "War of 1812" The first round of the "War of 1812" 1813 1813 1814 1814  The

Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815) The

Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815)The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 199-209. |

|

|

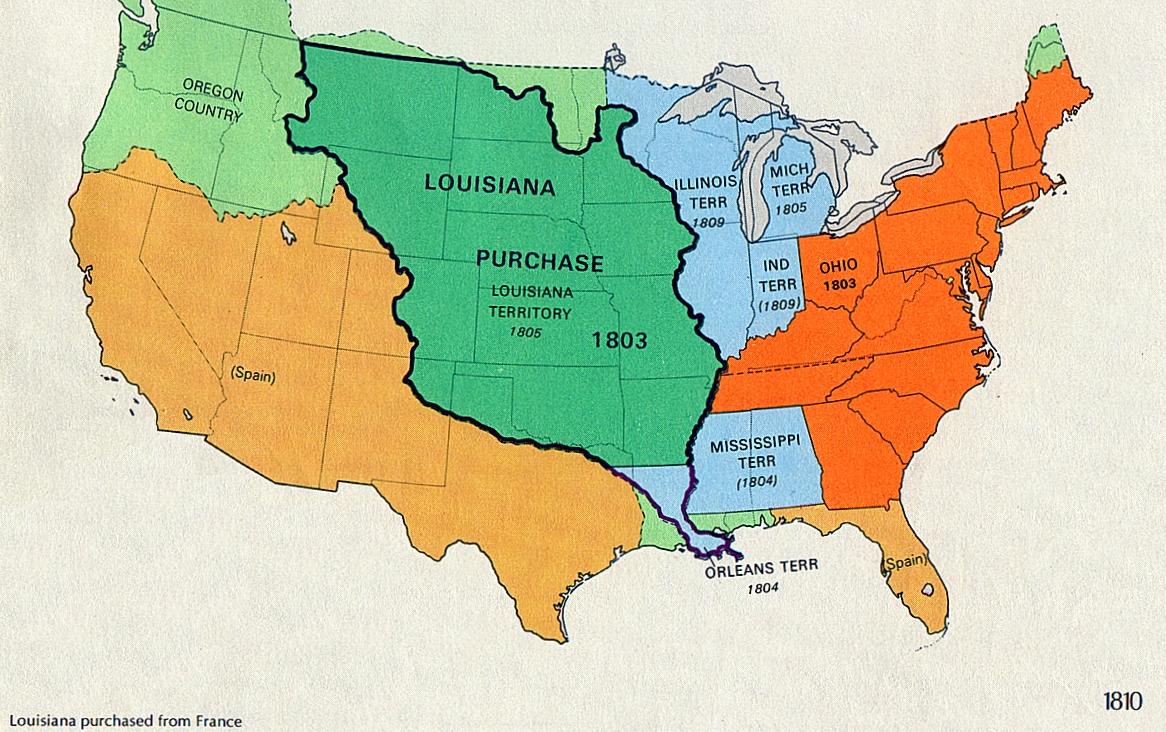

Jefferson's last years in the White House (he served two terms or eight

years) were tough on him, as tough as they had been for Washington in

his last years as U.S. president. The primary cause was the bitter

English-French feud stirred by Napoleon with his efforts to spread to

the rest of Europe, by military force if need be, French Enlightenment

ideals (that is, anti-monarchy ideals, and to a lesser extent

anti-church ideals). Although Napoleon clearly was a French dictator,

there was something about French culture that appealed to the

Jeffersonian Republicans. They also still harbored very strong

anti-British sentiments. On the other hand, the Federalists (who were

quickly dropping in political importance) looked to England rather than

France as their natural allies. But in any case, whatever the

sentiments, there was no way America, whose economy was built heavily

on trade, could stay out of the French-English conflict, even as

neutrals.

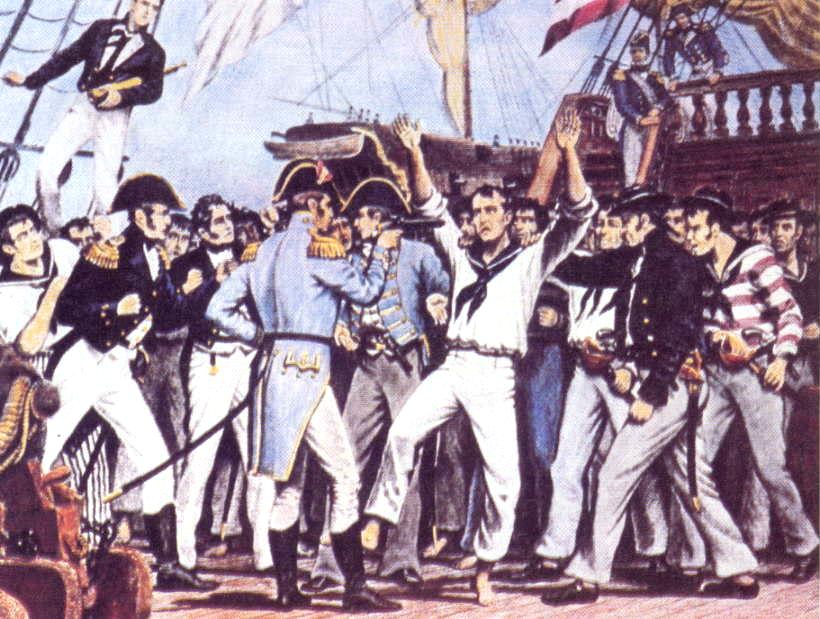

During these troubled times, the British had never ceased their impressment of American sailors. But in 1807 a British warship attacked an American warship just off the American coast when it refused to allow the British to board them for a sailor hunt. Americans were outraged and it was all Jefferson could do to keep his Republican Congress from pressuring him to issue a declaration of war against Britain. |

British board American ships to "impress" (force) sailors into British naval service

claiming that these were simply British escapees ... when in fact most were truly American.

|

What Jefferson did however was almost as ruinous

as war would have been at that time: he decided that somehow placing a

block or embargo on American trade with England would bring the British

to their senses (he had the idea that this would stir up worker unrest

in England!). His rather naive analysis blinded him to the fact that

this would actually put America in alliance with France, which was

trying to bring the English economy to collapse by a similar embargo

against English goods traded on the European continent, a continent

that Napoleon now dominated. The economic stakes were so high in the

British mind that this American embargo would only inflame them further

against the Americans, not bring them to their knees! He also failed to

realize that this policy would force American traders into bankruptcy,

or into smuggling. Hoping to placate the opposition which exploded when

he announced his embargo, he announced that the same policy would hold

true also with respect to trade with France. But this pleased no one

either.

To make bad matters even worse, Jefferson chose to meet the European challenge by not building more warships (frigates), the likes of which had proven themselves so capably in the war with the Barbary states. He figured that not having a fighting navy would help keep Americans from making the mistake of wanting to go to war with either France or Britain.1 Instead he chose to build a number of much smaller gunboats. These would not be terribly effective in defending American shipping overseas, but certainly could be used to help prevent the American smuggling that his embargo encouraged. Such dangerous folly did not escape the notice of the American press, even bringing fellow Republicans to loud complaint. But Jefferson stood firm, and thus finished his second term in the midst of a national uproar. However in early 1809, he finally saw the logic in repealing the much-hated embargo, just prior to his junior colleague, Madison, taking office as the country's next president. 1Liberal

Humanists such as Jefferson have always supposed that it is weapons

that cause wars – and thus disarming the people will automatically cut

back on the dangers of the people falling into a war with someone else.

But in fact self-disarmament – that is, disarmament if not mutual on

the part of all contending societies – will merely undercut the ability

of a society to protect itself against another society that has come to

hold such power that it no longer fears the consequences of its efforts

to bully others into submission. Weapons are not the problem. The

political-moral intentions of societies are what are critical in

matters such as this. |

|

|

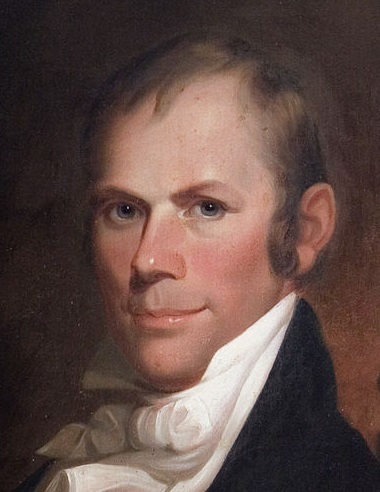

Madison had started out as an ardent Federalist, one of the co-authors

(with Hamilton and Jay) of the Federalist Papers advocating brilliantly

the acceptance of the federal Constitution. But with time he found

himself swinging his loyalties behind Jefferson, who looked upon the

national government with deep suspicion as a potential confiscator of

the rights of the states and their people. Then when the strongly

pro-Federalist Hamilton purposely built up the powers of the central

government through a policy of attaching it to the interests and thus

support of the moneyed banking and industrial class – and when

Washington and Hamilton began to swing their support behind the English

in their war with the French at a time when Madison's mentor,

Jefferson, had brought Madison strongly into his pro-French camp -

Madison found himself jumping fully into Jefferson's Anti-Federalist

faction, which he then helped organize as a proper political party: the

Republicans.

Madison was an individual of varying opinions, highly supportive of the idea of intellectual or ideological variety itself being a very healthy approach to life, not just for himself but for society in general. He came to this viewpoint through his own personal development. He was raised conventionally enough as a Virginia Episcopalian of a highly respectable bloodline, but instead of attending the Episcopalian College of William and Mary he headed off to Presbyterian Princeton, where he came under the direction of its president, Witherspoon. Presumably he studied theology under Witherspoon, but stayed on after graduation to continue the studies in Enlightenment philosophy. He returned to his family home at Montpelier and became involved in local politics, supporting not only a distancing of Virginia from increasingly aggressive royal authority, but also the disestablishing of the Church of England, in favor of religious freedom. Of rather poor health, he would serve during the war which soon broke out as a political voice rather than a military officer on behalf of Virginia, participating in the discussions and the drafting of the numerous documents that clarified Virginia's political goals in the war. He was brought on the governor's council of state and also the Second Continental Congress, developing a close relationship with Jefferson in the process. Madison became a very strong nationalist, working hard to reform the Articles of Confederation. But when that did not work, he continued the cause as a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. He helped prepare the Virginia Plan brought to the Convention, which started the debates, then personally kept notes on the entire proceedings (thus we have Franklin's prayer proposal!). And after the Convention he worked closely with Hamilton in writing numerous articles (the Federalist Papers) defending the new Constitution, as it faced the challenge of ratification. When the new Constitution went into effect, Madison was elected to the House of Representatives – after overcoming considerable opposition from his Anti- Federalist rival Patrick Henry and Henry's ally James Monroe by promising to push for the passage of a number of amendments to the Constitution securing the civil rights of the Americans. And this he did, helping greatly in authoring the First Ten Amendments or Bill of Rights. During Jefferson's eight-year presidency Madison had served loyally as Jefferson's secretary of state and right-hand man, and was the obvious choice of the Republicans to take over the presidency when Jefferson was ready to leave office. For Madison it was an easy glide into office (Madison secured almost three times the electoral votes as his Federalist opponent). But nothing after that remained so easy. Madison tried hard to pacify the British, but the British were not interested in changing their policies toward America. Then the Republicans in Congress weakened America's diplomatic hand further by cutting deeply the funding for the army and navy!2 2Jefferson

and his Republicans also had the strong notion that state militias, not

a standing federal army, provided the country its best defense. They

identified a standing army with the tyranny of European kings and

emperors and the militias with democracy. |

James Madison

He took over from his mentor Jefferson. But by this time the Republicans were a youthful

group, very different from the staid Virginian aristocrats who had formerly directed the party.

|

|

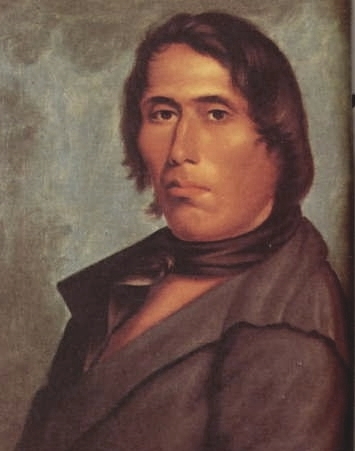

Tecumseh

But this unwise reduction of the U.S. army also

weakened the

defense of the American settlers along the frontiers with the Indians,

at a time when the Indians were deeply involved in military alliances

with the British. Thus it was that while American relations were

worsening with the British over their treatment of the U.S. navy and

its sailors, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet,

organized for war. Tecumseh gathered a huge Indian confederation

dedicated to driving White settlers from the Indian lands of the Great

Northwest. Although Tecumseh received a stinging setback by Harrison's

troops at the Battle of Tippecanoe3 in 1811, his confederation

continued to give serious trouble to the White settlers in the Great

Northwest. And when the War of 1812 broke out the next year, he was

quick to join the British as an ally against the Americans. 3Thus gaining fame for Indiana Governor and commanding officer Gen. William Henry Harrison, who with his men bravely stood their ground when, instead of meeting to discuss peace, the Prophet attacked the White army that had come to meet with him. The Harrison victory was such that it undercut the Prophet's standing among the Indians, and later (1840) had Harrison elected as U.S. President. |

Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, "the Prophet"

|

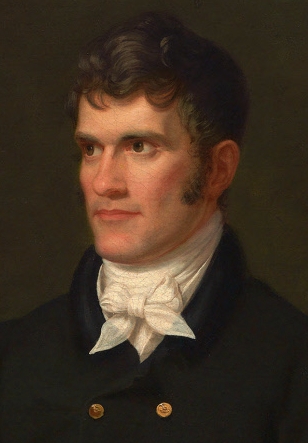

The rise of the young Republican War Hawks

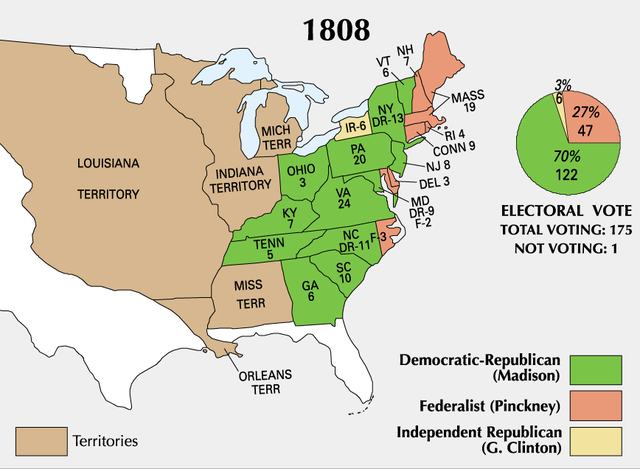

The Republican Party was beginning to register the first of a generational change from the older Jeffersonian Republicans to a younger breed of Republican activists. They soon came to be known as the War Hawks – Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina prominent among them.4 They demanded action: action against the Indians who attacked American communities on the frontier and action against the British who armed the Indians and who insulted America on the high seas with their policy of impressment of U.S. sailors. National fervor was definitely on the rise. In this, the younger Republicans seemed to be departing from the original principles of the Republican Party set out originally by Jefferson (the priority of the states over the nation). In many ways they were acting more like the Federalists of an earlier generation. Even Madison found himself swinging back to his earlier, more Federalist, attitude as the nation came under greater threat. War is declared5

Tragically, Congress went to war without considering how it was that Americans were supposed to fight, much less win, this war after having previously cut back the army and the navy to a pitiful status. 4In fact, many young Federalists had joined the growing Republican Party, helping to reduce further the size and impact of the Federalist Party, but also helping to promote this new nationalist look among the Republicans. This group of new Republicans included even John Quincy Adams, son of the ardent Federalist and former U.S. President John Adams. 5A

large number of Federalists were strongly opposed to the war and did

not support it militarily or financially. When America finally emerged

from the war not only with its honor intact, but buoyed up by an even

stronger sense of American nationalism, Americans turned strongly

against the Federalist Party, causing it nearly to cease to exist. |

Young Republican "War Hawks" Henry Clay (Tennessee)

and John C. Calhoun (South Carolina)

The young War Hawks pushed strongly for war against the British.

The New England Federalists were adamantly opposed to such a war

... and even contemplated seceeding from the Union over this matter.

The Fourth of July 1812 in Philadelphia ... a time of innocence about to be ended by

the coming war with the British

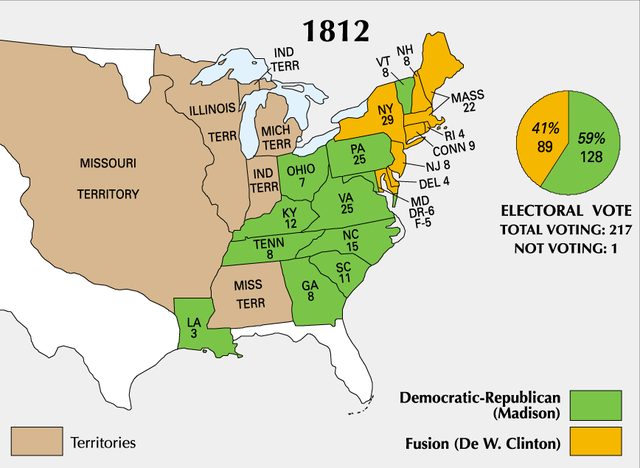

The 1812 elections: a huge victory for the Republicans ... the Federalists losing momentum

|

|

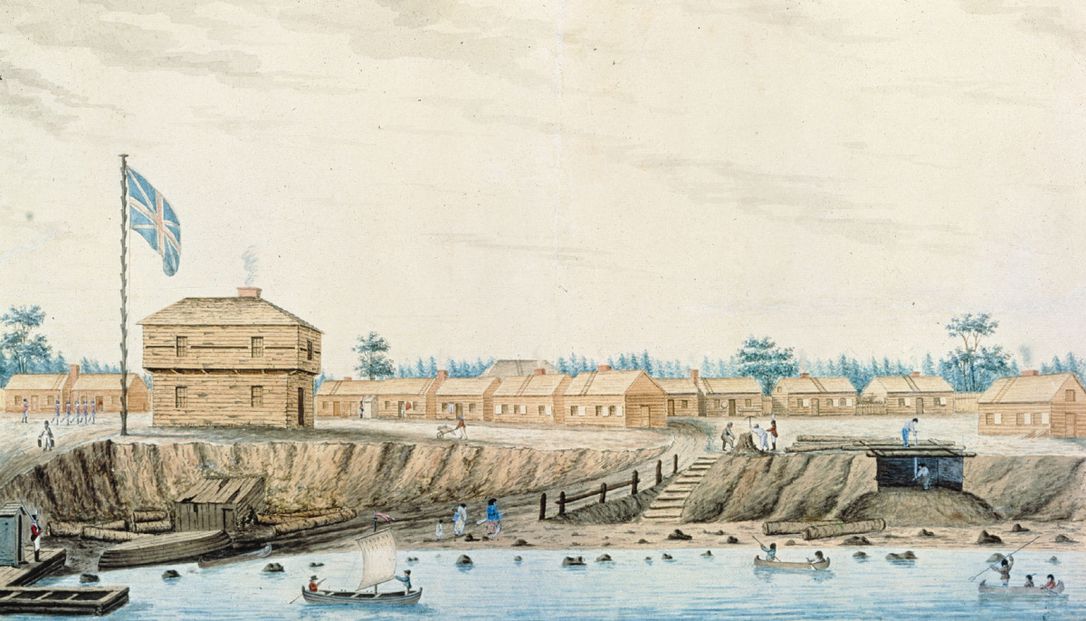

Immediately things went badly for the Americans. The Americans expected

an easy time in conquering sparsely populated Canada. But the British

were quick to respond, seizing Fort Mackinac in July before the

Americans at the fort were even aware of Congress's declaration of war.

This bold move so encouraged the Indians that they eagerly joined the

British in the attempt to break the power of the Americans in the

Northwest Territories. The British, who were in the midst of this huge

war with Napoleon's France and thus unable to supply a large English

military force in North America, were more than willing to accommodate

the Indians in their desire to crush the Americans.

An American army under General William Hull immediately invaded Canada, only to find that the Canadians were of no mind to surrender. The British responded to Hull's move into Canada by moving around him toward Detroit, which Hull realized he could not protect. Fearing a Shawnee massacre, in mid-August he ordered the Detroit garrison simply to surrender. The Fort Dearborn Massacre (August 15, 1812)

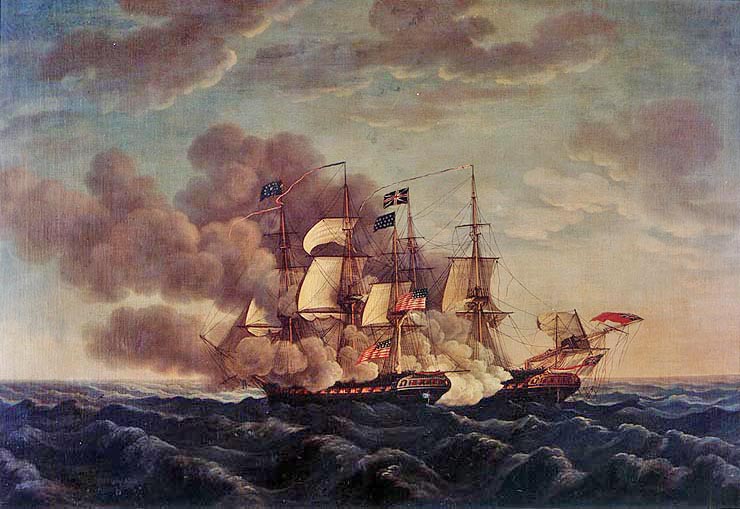

Likewise, fearing that the Americans would not be able to hold on against the British and Indians at Fort Dearborn (Chicago), Hull at the same time ordered the soldiers and militia stationed there to abandon their position and retreat east toward safer territory. The retreating Americans were promised safe conduct through Potawatomi territory by the local Indian chief. But younger Potowatomie warriors set upon them (including their supposed Miami Indian allies) almost immediately and slaughtered not only half of the soldiers and militiamen but also some of the women and nearly all of the children, carrying off the rest for ransom or slavery. Of the 132 Americans involved, only 15 managed to escape. Americans were outraged at the news. This Indian victory would in the long run cost the Indians dearly. It would also cost Hull his command. He was replaced as commanding general by America's Tippecanoe hero, William Henry Harrison. On the high seas Americans performed much better, though against a navy as immense as the British navy (175 warships and 600 ships overall!), that hardly made any strategic difference in bringing the war to an American victory. But psychologically, events such as the defeat of the English frigate Guerrière by the American frigate Constitution in August were a shock to the British and an enormous boost to American morale. Other naval engagements that year also played to the American advantage. |

Michel Felice Corne – combat

between USS Constitution and HMS Guerrière (August 19, 1812)

U.S. Naval Academy

Museum

|

|

Things were again off to a bad start for the Americans as 1813 rolled

around. In January a large detachment of militia from a number of

American states (including Kentucky) was defeated in a failed attempt

to retake Detroit (nearly 400 killed and over 500 taken away to Canada

as prisoners). Wounded Americans were left behind, only to be

slaughtered by Indians that the British could not control.

Thus American bitterness against the Indians only deepened. And the Kentuckians became more resolved than ever to bring the British – but especially their Indian allies – to defeat. But the Americans would make a huge mistake in Canada when in April of that year they attacked the capital of Upper Canada at York (modern Toronto). The American victory was costly (including the death of the American commander Zebulon Pike). But the worst part of the mistake was when the American officers lost control of their men, who proceeded to plunder and burn the town, stirring among the British and Canadians a determination for revenge. They would soon have that opportunity at Washington, D.C. |

|

Then the Indians struck again in late August, this time in the deep South at Fort Mims, Alabama. A branch of the Creek Indians called the Red Sticks harbored a deep hatred of the Whites – and also of their fellow Creek tribesmen who had been more accommodating to the Whites. The Red Sticks overran the Alabama fort containing around 500 men, women and children: White, Black (slaves) and mixed-breed Creeks. A large number of the White militia were killed in the action, as well as women and children (burned to death when they took refuge in an inner stockade that the Indians torched). About 100 of the Blacks were spared their lives, but taken off to slavery nonetheless. Only a small group (fifty of the original 500) escaped the massacre or enslavement. After this event – and the Fort Dearborn massacre – Anglo sympathy for the Indians was virtually nil at this point. |

|

In the meantime, finally realizing the foolishness

of the previous naval cutback, Congress voted to construct six more

frigates, thus giving the American navy a total of twelve warships!

However, though small in number, they gave good account of themselves

when facing the British. But just as important, American privateers

were very active capturing British merchant ships. Yet overall, the

British presence on the high seas was so vast that this hardly slowed

up the British. They replaced lost British shipping faster than the

Americans could bring down British ships.

On the Great Lakes that stood between New England and Canada both sides raced to build up their fleets of fighting ships. Battles on the water and in the coastal towns raged back and forth inconclusively, though with much loss of life and destruction of property. Americans made an attempt to capture Montreal, but failed miserably in the process. But two American victories would more than compensate for the failure to take Montreal. In September on Lake Erie, an American fleet under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry soundly defeated a British fleet sent out to destroy the Americans, and thus gave America control of the all-important Lake Erie. Now the way was finally opened to recapture Detroit. Then in early October the Americans met up in Ontario with a retreating British army and with Tecumseh and his Indian confederation. In the Battle of the Thames, Tecumseh was killed and the British army soundly defeated. With the news of Tecumseh's death, the Indian resistance collapsed. Indeed, his death would mark the collapse of his huge Indian confederation. All in all, it was a major American victory. |

The Battle of Lake Erie – September 1813

Americans under the command of Captain Oliver Hazard Perry

soundly defeated the British in this strategic battle

The Battle of the Thames (Ontario) – October 5, 1813

The British were again soundly defeated ... and Tecumseh killed.

The Indian Confederation fell then apart.

|

| The Americans took their revenge on the Red Stick Creeks the following March in nearby Mississippi when General Andrew Jackson led his Tennessee militia, allied with Cherokee and friendly Creeks, against the Red Sticks at Horseshoe Bend. The slaughter of the Creeks was extensive (800 of the 1,000 Creek warriors killed; Jackson's side lost only 49 killed), breaking the power of the Red Stick Creeks – and establishing General Jackson as a military hero. |

|

When Napoleon finally was brought to defeat in

Europe in May of 1814, the British were then able to turn their

attention more closely to the war going on between America and Canada.6

They devised a grand strategy to hit the United States from three

directions: from Canada in the North, up the Chesapeake Bay toward

Washington and Baltimore in the East, and at New Orleans in the South.

However, both sides, American and British, were tiring of the war. A British blockade of American ports had reduced American shipping and trade to a point of near economic collapse. But the British were becoming war weary, taxes were running very high, and trade with Canada and the British Caribbean was suffering. Thus both sides agreed to meet in August in Ghent (Belgium) to explore the possibility of peace. But the English, feeling that they had the military upper hand in the negotiations, demanded full British naval control of the Great Lakes, unrestricted access to the Mississippi River, and the creation of an Indian buffer state between Canada and the United States. The Americans were incensed at these demands. But British voices (including England's military genius and hero Arthur Wellington) also objected to these demands as being highly unreasonable and not likely to bring the troubles to an end (in this they were quite correct!). However, the defeat of Napoleon had also taken care of some of the issues that had brought America to war in the first place. Britain was no longer on a war footing and therefore the British no longer felt the need to pursue the impressment of sailors. With the war with Napoleon seemingly over,7 there was no longer any need to block American shipping to France or the French colonies in the Caribbean. Nonetheless the war with America continued. The British burn Washington, D.C.

Americans were stunned by the arrival of the British fleet in the Chesapeake Bay in August. The American effort to fend off a large British army put ashore near Washington, D.C., failed miserably. The Americans were unorganized, poorly led, and poorly equipped to face this experienced British army. The British proceeded to humiliate the American militia gathered at Bladensburg on August 24th as they advanced on the American capital. The commanding American general lost his nerve, and he and his men fled (as did Madison and his presidential cabinet), leaving the capital open for the British to enter that evening. Then the British proceeded to burn to the ground: the White House, the Capitol building, the Library of Congress, and anything else of value. In part this was done as repayment for the American action in York (Toronto) the previous year. 6Napoleon was exiled at the end of May in 1814 to the island of Elba off the Italian coast. 7Or

so it seemed at the time. However, in March of 1815 Napoleon would

escape from the island of Elba to the mainland of France, gather a new

French army and begin again his attacks on Europe's monarchs. But his

Hundred Days was brought to a close in July when a grand coalition of

Austria, Prussia and Britain met and defeated him at Waterloo. He was

then banished to an island in the middle of the South Atlantic, where

he lived out his days as a comfortable prisoner. |

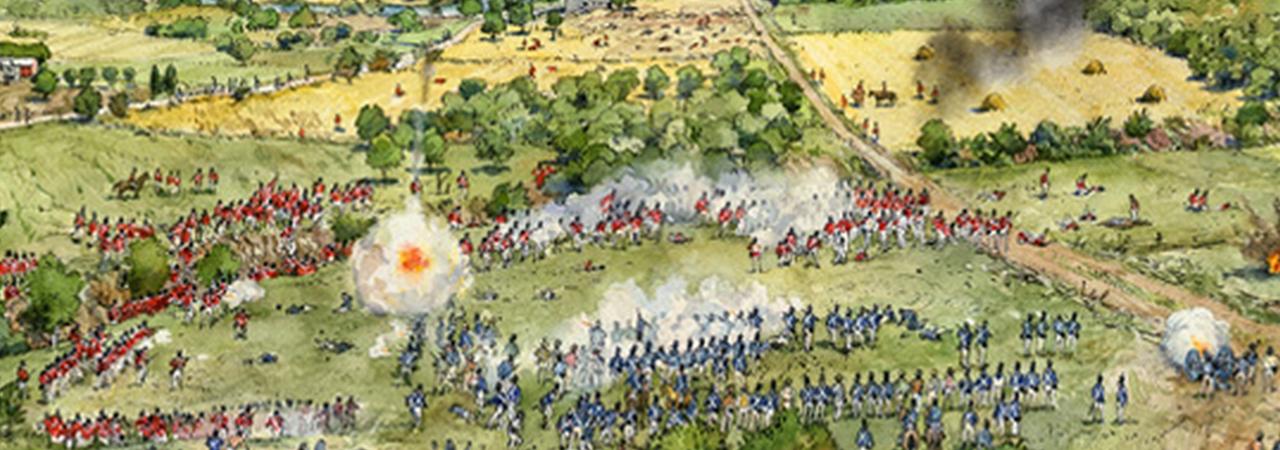

The British assault on Washington, D.C. – August 24, 1814

The Battle of Bladensburg – August 24, 1814

The poorly prepared and poorly led American troops were completely routed

by the British troops, leaving DC open to British assault.

British troops burning an abandoned White House on that same night.

First Lady Dolly Madison had already removed all the documents

and other valuable items ahead of the arrival of the British troops.

George Munger – The unfinished

United States Capitol after the burning of Washington

Library of Congress

|

The Battle of Fort McHenry

From there the

British headed confidently up the Chesapeake Bay toward Baltimore in

September, but with a very different outcome this time. American

militia stopped the British at North Point. And Fort McHenry, guarding

Baltimore, held out boldly against the heavy bombardment from the

British ships on September 13th.8 Thus, unable to get past this

unyielding resistance, the British finally withdrew, all the way back

to Jamaica. 8A witness to this British failure at Fort McHenry was Francis Scott Key, who wrote a poem about the flag remaining aloft through the night of heavy bombardment. The poem was eventually put to music and became the American national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner. |

|

American victory on Lake Champlain

Meanwhile a major American victory took place on September 11th on Lake Champlain in New York, when a British fleet attempting to extend English control into the heart of the American nation was soundly defeated, losing three British ships to the Americans in the process. This fairly well ended the part of the grand plan to squeeze the Americans from the north. At this point the British turned their attention to the part of their grand plan which included the assault on New Orleans, scheduled for the beginning of 1815. |

The naval battle at Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain (September 11, 1814)

Meanwhile, by the end of October, both the British and Americans seemed

to agree that the best thing to do was simply return things to the way

they were before the war (status quo ante bellum), and began to

fine-tune a treaty, which the diplomats of both sides signed on

December 24th. British Parliament approved the treaty three days later,

and it went by sea to America, arriving in mid-February of 1815. The

Americans were also quick to approve.

The Treaty of Ghent (Belgium) – Christmas Eve, 1814

Wars have huge

psychological/spiritual (as well as political) consequences – for both

the winners and the losers. For the American Indians, their power had

been rather permanently broken by the war. From then on, the Indians

would be forced on a continuing retreat, fighting as they went, but

retreating nonetheless, with little likelihood that they would ever be

able to stem the flow of Anglo Whites into their lands.

As for the Americans, they now experienced a new

sense of being American nationals, as well as (and maybe even more

importantly than) Virginians, or New Yorkers, etc. And the war had put

a new name on their lips: General Andrew Jackson, a person with an

obviously major destiny ahead of him as a national leader.

The war would also mark the death of the

Federalist Party. Federalists had resisted the war effort every way

legal, and often illegal (trafficking with the British enemy).

Interestingly, they now took the states'-rights position of the older

Jefferson Republicans, just as the Republicans were turning

increasingly nationalistic. The Federalists were bitter about the

complete Republican domination in Washington, accusing Republicans of

everything imaginable, including even being nothing more than Jacobins

(the butchers of the French Revolution).

So alienated were the Federalists by political

developments that they even met secretly in Hartford, Connecticut

(mid-December 1814 to early January 1815) to consider New England's

secession from the Union, even as the Treaty of Ghent ending the war

was being finalized. The timing could not have been worse for the

Federalists. Jackson's victory at New Orleans had the American national

spirit running so high that the Federalists now appeared to be even

treasonous. The Federalists backed down from their call for secession.

But it was too late anyway. As a party, they were finished.

The last two years of Madison's eight-years as president were largely

without major controversy or issue. The nation was ready to get back to

the business of growing, economically and territorially. Madison

sponsored tariffs to protect a growing American industrial sector and

busied himself in securing federal grants for the states for the

building of roads and canals to link the interior with the East coast.

He even backed down from some of his earlier Jeffersonian tendencies,

bringing back into existence in 1816 a second Bank of the United States

(BUS)9, and supporting the establishment of a professional military. At

this point he was again definitely following in the footsteps of his

once friend Hamilton – not his former mentor, Jefferson.

But a huge controversy arose in the very last days

of his presidency over the Bonus Bill of 1817. It called for profits

and dividends from the new national bank to be used to fund more roads

and canals. Though Madison was a supporter of exactly just such

internal development, he felt that the Constitution did not allow for

the federal government itself to become involved directly in this

action. He thus vetoed the bill just prior to leaving office. In this

he was drawing from his former Jeffersonian dislike of empowerment of

the national government (over the states). But he was also treading on

the ground of an issue that would come increasingly to trouble all

national politics: the growing sectionalism that seemed to arise over

every issue. For one thing, development of the West, at the expense of

Eastern financial interests, drew off workers necessary for development

of the eastern industries. But for another, it constantly raised the

question: is a rising Western territory to develop as a slave or free

state? 9Madison

and the Republican Congress had earlier refused to renew Hamilton's

Bank of the United States (BUS) when its charter expired in 1811.

At the same time, the Americans delivered the British another huge blow

with their naval victory at the Battle of Plattsburgh.

Both huge victories, plus the end of the British war with Napoleon,

would lead the British to want to make peace with the Americans.

However, in the South, along the Gulf coast,

Americans were holding fast against British efforts to gain a foothold

there. The British gathered at Pensacola (Florida), but were easily

overrun by General Jackson's troops. Jackson then moved to New Orleans,

suspecting (correctly) that this would be the next British target.

![]()

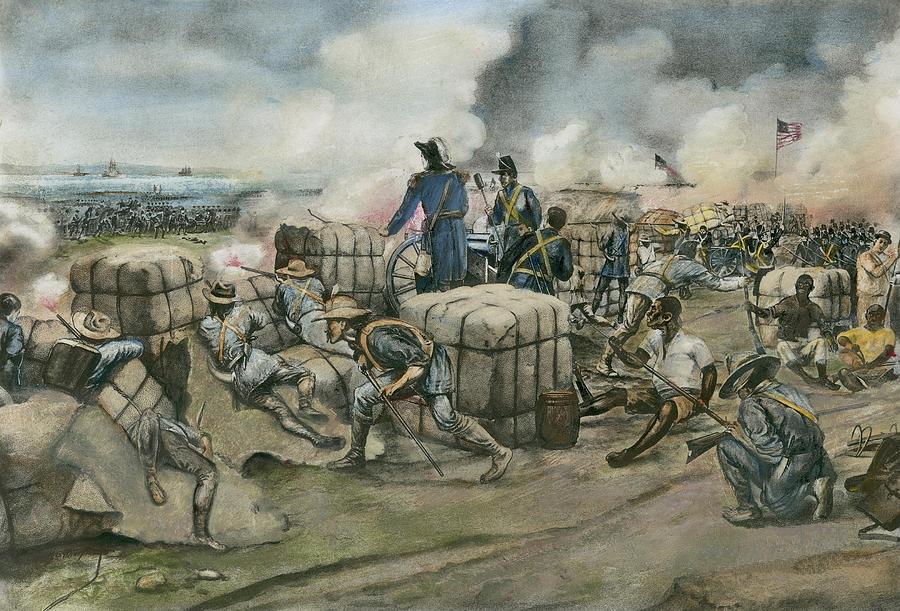

(January 8, 1815)

On

the Gulf coast, neither the British nor the Americans were aware that

the Treaty had been signed in Ghent, and on January 8th, they proceeded

to battle. Jackson's men were unwavering against multiple British

assaults on well-held positions outside the town. Jackson's troops were

well-protected by a wall of cotton bales they had erected against the

advancing British, whose guns were totally ineffective in breaking down

the American defenses. The net result was a disaster for the British:

291 British dead against 13 American dead, 1,262 British wounded

against 39 Americans wounded and 484 British captured or missing.

Although the battle took place after the war was officially over, it

had its own very serious consequences: America had indeed established

itself as a strong nation not to be taken for granted.

The Americans obliterate the British in their attempted assault on New Orleans

(January 8, 1815)

Go on to the next section: The "Era of Good Feelings"

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges